Volume 17, Issue 3 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(3): 299-307 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2025/05/20 | Accepted: 2025/07/18 | Published: 2025/07/30

Received: 2025/05/20 | Accepted: 2025/07/18 | Published: 2025/07/30

How to cite this article

Mousavi B, Behzad Basirat Z. Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Sulfur Mustard Exposed Survivors; An Analytical Review. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (3) :299-307

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1596-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1596-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

B. Mousavi *1, Z. Behzad Basirat2

1- Prevention Department, Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

2- Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

2- Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (11 Views)

Introduction

Chemical warfare is one of the most brutal types of weapons of mass destruction, primarily using toxic agents to kill or incapacitate enemies [1]. Despite the Chemical Weapons Convention banning chemical weapons in 1993 due to the profound impact on human health and international security, some countries continue to produce them [2]. Chemical weapons are among the most inhumane weapons of warfare due to the severe acute and chronic health complications. The first large-scale use of chemical weapons after World War II occurred during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. Sulfur mustard (SM) is a potent alkylating agent that binds to proteins and nucleic acids, induces cellular necrosis, and leads to severe complications from inflammation to mutagenic and even carcinogenic outcomes. SM was originally synthesized in 1822 and was first employed in warfare by the German army in 1917 against both Canadian and French forces, and later by the British during the 1918 Hindenburg campaign. Several other nations, including Spain, Italy, the Soviet :union:, Japan, and Egypt, utilized sulfur mustard in military conflicts. Throughout the conflict (1980-1988), Iraq extensively used SM in many military operations. United Nations investigations have verified the use of SM through field assessments and clinical evaluations of exposed individuals. There are short- and long-term complications in various organ systems among survivors of SM exposure. The studies show that SM has different effects on the lung, skin, and eyes [3]. A notable example of chemical warfare occurred during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), where Iraq used sulfur mustard (SM). This potent alkylating agent has severe health effects, including chronic inflammation and long-term complications [4]. SM could cause mild conjunctivitis in the eye, skin, and pulmonary system, through delayed and severe chronic complications. Survivors may suffer from blindness, obstruction of the upper airways, chronic bronchitis, and bronchiolitis in the lung, and many known or unknown disorders [3]. The higher rate of health problems leads to an increase in the utilization of medical health services and medical costs among chemical warfare survivors and their families over time [4-9].

The medical expenses increase due to frequent need for hospitalizations, paraclinical, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation [5]. Recent studies on sulfur mustard have shown that it alkylates cellular components and induces the expression of a variety of inflammatory biomarkers that cause DNA damage and impair cellular function [10]. The immune system produces inflammatory factors to fight pathogens and facilitate healing. Still, persistent elevation of these markers leads to chronic inflammation, which is associated with diseases such as arthritis, asthma, autoimmune disorders, neurological diseases, diabetes, cancer, and conditions of aging [11], as well as mental disorders [6]. In terms of pathology, inflammation is one of the adaptive responses to numerous injuries caused by physical, chemical, and biological factors. The common signs of inflammation are related to tissues and cells responding to pathological injury induced by internal or external stimuli and damage-associated products and metabolites. The biomarkers provide important insights into the status and severity of inflammation, helping to predict patient outcomes, diagnose diseases, and monitor treatment [12]. This study examined the effects of sulfur mustard exposure on chronic inflammatory biomarkers, including pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, in SM-exposed survivors over time.

Inflammation is a complex biological phenomenon that resists a simple, universal definition. Depending on the context, it can be understood as a response to disturbance (such as infection), a process involving a series of defensive mechanisms aimed at eliminating the cause of that disturbance, or a state that may be pathological or protective. Each perspective highlights a different facet of inflammation. Renewed interest in the field has been driven by the recognition that inflammation is linked to nearly all human diseases. Moreover, emerging evidence shows that the cellular and molecular mediators involved in inflammation also participate in a wide array of biological functions, including tissue remodeling, metabolism, thermogenesis, and even nervous system activity. There are two types of recognition of inflammatory inducers: external and internal responses that trigger inflammation, which influence damage in retrospective and prospective modes. The prospective mode involves detecting potential threats before any tissue damage occurs. Pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) trigger inflammation. This allows the immune system to respond preemptively, even in the absence of actual pathogens, thereby limiting potential harm. Prospective recognition is advantageous because it enables early activation and potentially prevents tissue damage altogether. Similarly, other inflammatory inducers, such as toxins, can be recognized by their characteristic activities, enabling early (prospective) detection and response before significant harm is done to the host [13].

Chronic inflammation is a long-term state of continuous immune system activation, often due to persistent infections, autoimmune diseases, or chemical irritation, and can lead to various diseases [14]. Cytokines (including interleukins, interferons, tumor necrosis factors, and chemokines) play diverse roles in modulating immune responses, exerting both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects through intricate biochemical pathways and cellular interactions. Recent advances in immunology have led to a deeper understanding of the stimuli that trigger cytokine release, their mechanisms of action, and their downstream effects on immune regulation and tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, clinical research has increasingly implicated specific cytokines in the pathogenesis of various diseases, highlighting their potential as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets. When the immune system encounters pathogens, it secretes inflammatory factors in two stages: Pro-inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and BDNF) and anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13). Imbalance in the expression of these factors causes chronic inflammation [15]. Cytokine levels provide insights into the presence, severity, and progression of chronic diseases. Emerging evidence suggests that inflammation actively maintains the functional and structural integrity of tissues and organs. Understanding these physiological functions of inflammation could provide deeper insight into both the biology of health and the pathophysiology of disease. This study investigates the long-term effect of sulfur mustard on chronic inflammatory biomarkers in exposed survivors, including pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Cytokines

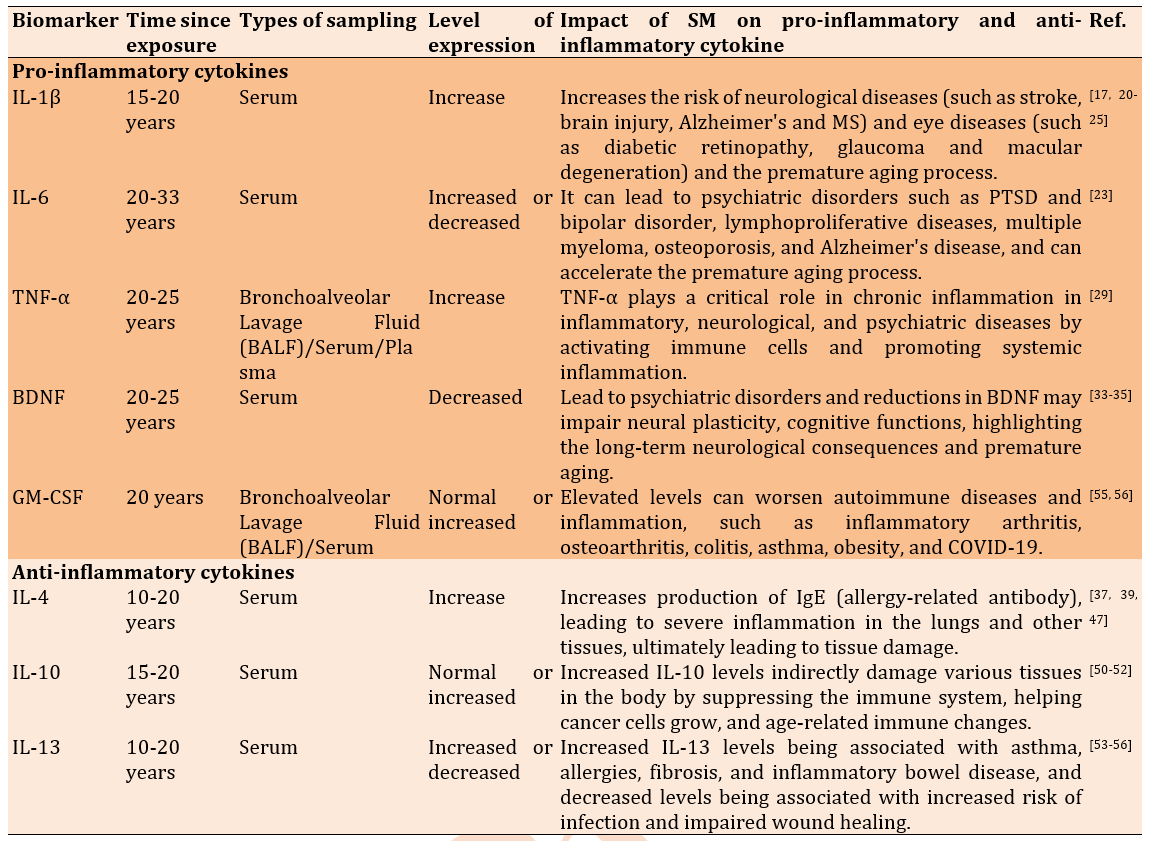

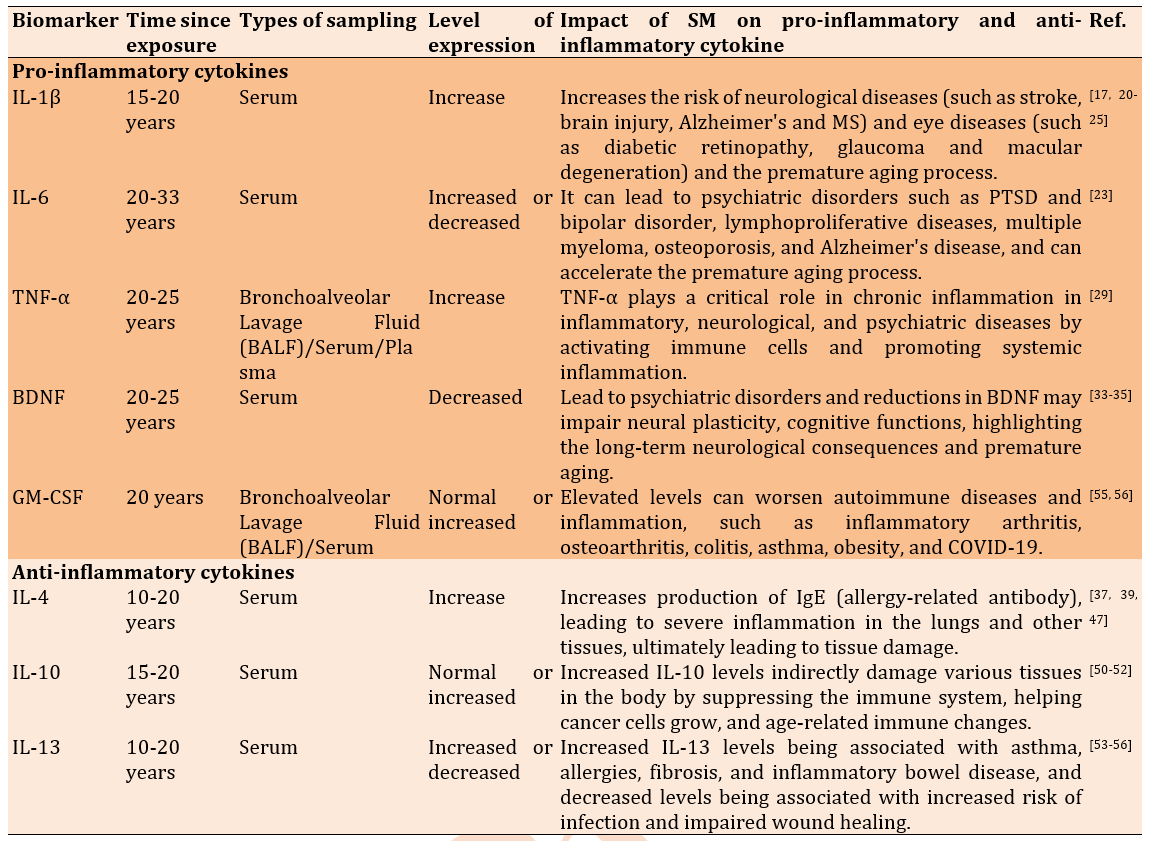

Cytokines are low-molecular-weight glycoproteins that play a central role in mediating immune cells and inflammation. Historically, cytokines have been classified into several subgroups based on their initially discovered functions, including interleukins (ILs), interferons, cytotoxic cytokines, colony-stimulating factors, chemokines, and other cytokines. Cytokines are often defined as interleukins produced predominantly by immune cells. These include cytokines associated with innate immunity—such as IL-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-6 —as well as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, which help regulate immune responses and maintain immune homeostasis. Cytokines are highly potent biological molecules that exert their effects at picogram concentrations. Cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 are small proteins and glycoproteins that are key biomarkers of chronic inflammation, reflecting sustained immune activity and underlying disease processes. These can be assessed in biological samples to monitor inflammatory status, track disease progression, and even inform treatment strategies for chronic conditions and diseases. However, their routine use is often constrained by technical and analytical limitations [16] (Table 1).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines

Pro-inflammatory cytokines include IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, BDNF, and GM-CSF. Sulfur mustard exposure has impacted each biomarker as follows:

Interleukin 1β

Interleukin 1β (IL-1β) is a key cytokine that promotes inflammation [17]. IL-1β, produced by activated macrophages, plays a fundamental role in the immune response to tissue injury and infection. IL-1β plays a role in resolving acute inflammation, and higher expression of IL-1β is associated with cell injury. When the balance of IL-1 level is disrupted, it may markedly contribute to the pathogenesis of both inflammatory disease and conditions that increase the risk of developing cancer. IL-1 is an attractive molecular target for treating a wide range of diseases, particularly autoinflammatory, autoimmune, infectious, metabolic syndrome, ischemic, and malignant tumors [18]. The effect of sulfur mustard on interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) has been of interest as an important inflammatory marker in many diseases [19]. Studies have shown that exposure to SM increases IL-1β levels and contributes to chronic inflammatory processes, which in turn increases the risk of neurological diseases (such as stroke, brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, and multiple sclerosis) and eye diseases (such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and macular degeneration) [17, 20-25]. This increased production of IL-1β is associated with the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways and the stimulation of immune responses, which can contribute to the development and progression of tissue damage and inflammation [26]. In clinical and preclinical studies, the toxic effects of SM on macrophages and other immune cells have been evaluated, and the results indicate that this substance can induce IL-1β expression through the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [27]. These processes, in turn, can lead to serious side effects and disease progression [28, 29]. Studies have shown that Sulfur mustard induces chronic inflammation by altering the expression of inflammatory cytokines, among which IL-1β, overexpressed, causes skin diseases [30].

Interleukin-6

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is another important cytokine involved in regulating immunity and inflammation [31]. Increased IL-6 in response to sulfur mustard is associated with chronic inflammation, which is implicated in psychiatric disorders. High levels of IL-6 are associated with increased risk of psychological stress/disorders, PTSD, impairment of neuronal function/synaptic resilience, which may play a role in the occurrence of psychotic disorders [32]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has a multifaceted impact, influencing inflammation, immune responses, and hematopoiesis. Increased levels of IL-6 can weaken the body's protection against infectious diseases. Moreover, IL-6 increases insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, suggesting a role in metabolic processes. It is involved in the development of plaque and atherosclerosis. The effects of IL-6 are both positive and negative, depending on the specific biological context and the physiological or pathological condition. An increase in IL-6 is associated with lymphoproliferative diseases, multiple myeloma, osteoporosis, and Alzheimer's disease, and can accelerate the premature aging process [33]. A cross-sectional study investigated the mental and physical health of 227 veterans exposed to sulfur mustard (SM) and 77 healthy individuals. The findings revealed that veterans’ exposure to SM exhibited higher levels of anxiety, insomnia, and psychiatric symptoms compared to the controls (p<0.05). Interestingly, levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were lower in the exposed group. In comparison, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels were higher (p<0.05), indicating a possible partial improvement in their mental and physical health [34]. Another study measured interleukin-6 in two groups: exposed individuals (60 patients with pulmonary symptoms and mild to severe complications; n=60) and healthy non-exposed individuals (n=30). The average interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration in patients was 0.76±0.30pg/ml, significantly higher than the control group's 0.34±0.12pg/ml (p=0.17) [35]. Several studies indicated a higher rate of mental health in SM exposed survivors and even their spouses, as well [36-43].

Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is recognized as a pro-inflammatory cytokine with diverse biological effects. TNF-α regulates inflammation, host defense, immunity/autoimmunity, apoptosis, carcinogenesis, and organ development. TNF is recognized as a key mediator of inflammatory and immune responses. TNF signals to immune cells that kill tumor cells. TNF plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). TNF-α acts as an arbitrator of the local tissue environment after injury. It can initiate apoptosis, regulate cell survival and proliferation, and tissue regeneration and remodeling. Excessive amounts of cytokines cause widespread inflammation that damages organs and tissues [44]. Sulfur Mustard is a blistering agent that damages the skin, eyes, and respiratory system. One of the main mechanisms of its toxicity is the induction of an inflammatory response in which TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha), a key pro-inflammatory cytokine, plays an important role [45]. Exposure to sulfur mustard can increase the expression and secretion of TNF-α from various cells, including keratinocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes [46]. This raises the risk of some chronic connective tissue disorders with endothelial dysfunction, fibrosis, cancer, and premature aging. This finding is consistent with previously published studies indicating that sulfur mustard (SM) acts as a carcinogen even after a single exposure, regardless of dose or duration [9]. Chemical warfare victims with eye and lung injuries experience significantly more psychological disorders, poor quality of life, and limitations in daily activities. This is largely determined by persistent lifelong symptoms caused by both irreversible and progressive health complications. Poor outcomes are further influenced by factors including the severity of the initial injury, the presence of comorbid conditions, and associated psychological disorders [36, 37, 39-43, 47].

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor

Among all neurotrophic factors, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a crucial role in promoting neurogenesis, neuronal survival and growth, modulates neurotransmission, and participates in neuronal plasticity (essential for learning and memory). BDNF regulates energy metabolism and glucose metabolism and helps prevent β-cell exhaustion. Decreasing the levels of BDNF commonly associates with neurodegenerative diseases (such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis). BDNF also helps prevent and manage diabetes mellitus [48]. The exposure to sulfur SM has been shown to adversely affect BDNF levels, which are crucial for neuronal survival, growth, and function [49]. Limited studies have also shown that Sulfur mustard can induce neuro-inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to decreased BDNF expression [50, 51]. This reduction in BDNF may impair neuroplasticity and cognitive functions, highlighting the potential long-term neurological consequences of sulfur mustard exposure [52]. In only one study it has been showed that the level of BDNF in serum were elevated [34].

When individuals are exposed to sulfur mustard, the resultant inflammation and oxidative stress can disrupt the normal expression of BDNF [34]. Survivors exposed to sulfur mustard exhibit varying levels of this biomarker, and this imbalance may lead to psychiatric disorders and central nervous system diseases [53]. This disruption can result in lower levels of BDNF in the brain, leading to several potential consequences: First, can activate inflammatory pathways in the central nervous system. This inflammation can create an unfavorable environment for neurons and adversely affect BDNF signaling [54]. Second, reduced BDNF levels are associated with impaired cognitive functions, such as learning and memory. Individuals exposed to sulfur mustard may experience difficulties in these areas due to lower neuroplasticity [55]. It may have long-lasting implications, potentially leading to chronic neurological issues, including neurodegenerative diseases or cognitive decline [56]. Moreover, BDNF plays a significant role in the aging process [57]. Overall, the impact of sulfur mustard on BDNF levels underscores the need for further research to understand its effects on brain health and the mechanisms involved.

Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a growth factor that stimulates myeloid progenitor cells. Produced by various cells (T cells, phagocytes, etc.), GM-CSF enhances immune responses by generation of myeloid cell subsets including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells in response to stress, infections, and cancers and activating immune cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), and plays a critical role in regulating myeloid cell host defense [58]. The DCs, along with macrophages and monocytes, are antigen-presenting cells (APCs) whose function is enhanced by GM-CSF. GM-CSF works alongside other inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8) in regulating immunity and inflammation [59]. GM-CSF abnormal level (both low and high) can worsen autoimmune diseases and inflammation, weaken immunity, and impair wound healing. Elevated GM-CSF has been shown to contribute to inflammation in inflammatory arthritis, osteoarthritis, colitis, asthma, obesity, and COVID-19 [60], as well as accelerate aging [61]. The specific dangers depend on the extent and cause of the imbalance [62]. A study investigating the role of cytokines in sulfur mustard-induced pulmonary fibrosis examined bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from 18 sulfur mustard-exposed veterans with pulmonary fibrosis (PF) and 18 control subjects. Significantly higher levels of G-CSF and GM-CSF were found in the BAL fluid of exposed patients compared with controls. IL-8 levels were also significantly elevated. In addition, IL-8 and G-CSF levels correlated with neutrophil counts, while GM-CSF levels correlated with eosinophil counts in the BAL fluid of SM-exposed patients. The findings suggest that neutrophilic alveolitis, eosinophilia, and increased IL-8, G-CSF, and GM-CSF in BAL fluid are associated with the development of fibrosis in sulfur mustard victims [60]. In a cohort study in Sardasht, Iran, the effect of sulfur SM on GM-CSF levels was investigated in two groups of exposed (n=369) and unexposed (n=125) after 20 years. This study reported that serum GM-CSF levels were not significantly different between exposed and unexposed subjects. However, a positive correlation was observed between GM-CSF and eosinophil counts in the exposed group. Furthermore, this study found no significant association between GM-CSF levels and pulmonary function parameters [61].

Anti-inflammatory cytokines

Interleukin-4

Like many cytokines, Interleukin-4 (IL-4) can affect numerous target cells in several ways. IL-4 plays a significant role in the development of effector T-cell responses, regulating antibody production, hematopoiesis, and inflammation. IL-4 is a cytokine that plays a crucial role in the immune system, primarily involved in promoting the differentiation of naive T cells into T-helper 2 (Th2) cells [63]. IL-4 is also essential for the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) and the activation of mast cells and eosinophils, which are key players in allergic responses and asthma. Overproduction of IL-4 causes hyperactivation of lymphocytes, elevated IgE levels, and autoimmunity [64]. Following exposure to sulfur mustard, there is evidence of increased IL-4 levels due to its pro-inflammatory effects [65, 66]. Recent studies have highlighted the role of IL-4 in mediating the Th2 response in models of chemical exposure, including sulfur mustard [67]. This increased IL-4 production can contribute to a broader inflammatory response, exacerbating tissue injury and promoting airway hyper-responsivity [68]. Understanding the modulation of IL-4 following sulfur mustard exposure is essential for developing therapeutic strategies to manage inflammation and related respiratory conditions [69]. Veterans exposed to sulfur mustard have high levels of IL-4. This substance increases IgE production (an allergy-related antibody), leading to severe inflammation in the lungs and other tissues, ultimately causing tissue damage [70].

Interleukin-10

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is well-known for its potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects and is produced by T helper 2 cells. IL-10 is now known to be produced by various myeloid- and lymphoid-derived immune cells participating in both innate and adaptive immunity. IL-10 plays an essential role in modulating inflammation and maintaining cellular homeostasis. It acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine that protects against an uncontrolled immune response and has immune-stimulating functions. IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine that inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Excess IL-10 can indirectly damage various tissues in the body by suppressing the immune system, promoting the growth of cancer cells, and impairing wound healing [71]. Recent researches suggest that while IL-10 is increased following sulfur mustard injury, an imbalance in favor of inflammation can reduce the protective effects of IL-10, leading to long-term tissue damage and altered immune responses [72, 73]. In one study, the levels of the cytokines TNF-α in tears, and IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-6, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and FasL in the serum of 128 SM-exposed veterans with severe ocular injury were compared with those of 31 healthy controls. The results showed that in SM-exposed veterans, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), decreased tear breakup time (TBUT<10 seconds), and conjunctival, limbal, and corneal abnormalities were more common. The severity of ocular injury was mild in 14.8%, moderate in 24.2%, and severe in 60.9%. Serum levels of IL-1α and FasL were significantly higher in veterans, and serum and tear levels of TNF-α were significantly lower than in controls (p<0.001). Serum levels of FasL were significantly higher in cases with severe ocular injury than in controls (p=0.03). There was no significant difference in serum levels of IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-1α/IL-1Ra, and IL-6 between the two groups. Finally, increased serum levels of IL-1α and FasL may contribute to the development of ocular surface abnormalities in patients exposed to SM, and the decrease in TNF-α in tears is likely due to reduced serum levels of this cytokine [19]. A similar study indicated that the incidence rate of cancer was significantly increased in SM exposed survivors. The incidence rate ratio of cancer for SM exposure was 2 times higher than that of the general population. This study suggests carcinogenesis of SM following acute exposure to SM in the victims after 20 years of exposure [9].

Interleukin-13

Interleukin-13 (IL-13) is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that regulates IgE synthesis, goblet cell hyperplasia, and mucus hypersecretion and causes airway hyper-responsivity. IL-13 is an important mediator for allergic inflammation, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. IL-13 has effects on immune cells. It is suspected that IL-13 is the core mediator of the physiologic changes made by allergic inflammation in many tissues. IL-13 is involved in various processes, including airway remodeling, fibrosis, and mucus production regulation. High levels of IL-13 indicate that the immune system is overactive. This could be a response to an ongoing infection or disease that the body is trying to fight off [74]. Following exposure to sulfur mustard, IL-13 levels may be increased or decreased, with elevated levels associated with asthma, allergies, fibrosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. The decreased level of IL-13 is associated with increased risk of infection and impaired wound healing [75]. Recent studies have shown that IL-13 is often upregulated in response to airway irritants and is linked to the pathophysiology of asthma [76]. In the context of sulfur mustard exposure, increased IL-13 levels can exacerbate bronchoconstriction and contribute to long-term respiratory sequelae [77]. Treatment targeting IL-13 could mitigate the adverse effects associated with sulfur mustard-induced inflammation.

Table 1. Impact of sulfur mustard on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine

Conclusion

Sulfur mustard leads to significant changes in inflammatory markers, including pro-inflammatory (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory cytokines. These changes indicate activation of the innate immune system and initiation of a severe inflammatory response. SM exposure activates inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB pathway, which ultimately increases the production of additional pro-inflammatory cytokines. These changes appear to be a regulatory mechanism that controls the initial severe inflammatory response and prevents further tissue damage. Overall, SM causes a significant imbalance in both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory biomarkers. An initial and dominant increase in pro-inflammatory biomarkers causes widespread tissue damage. While the subsequent increase in anti-inflammatory biomarkers serves as a compensatory mechanism, it is insufficient to mitigate the damaging effects of inflammation alone. This imbalance in biomarkers is one of the important factors in the development of long-term complications after sulfur mustard exposure. These complications include chronic respiratory, skin, and eye diseases, as well as an increased risk of cancer. Numerous factors, including age, sex, adiposity status, and overall inflammatory state, can affect circulating cytokine levels. Therefore, it should be considered that, in addition to SM, cytokines may also be influenced by some of these factors. Future studies will focus on further developing the predictive biomarker modeling framework to extract predictive biomarkers from complex data. Additionally, combining biomarkers from different sources (imaging, molecular, clinical) can improve the accuracy of SM outcome predictions.

Acknowledgments: Finally, we would like to express our deepest gratitude to the esteemed directors of the Veterans Engineering and Medical Sciences Research Center, Dr. Abbas Vali and Dr. Zohreh Ganjparvar, for their moral support and participation in the present research process.

Ethical Permissions: Not needed.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have not reported any conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Mousavi B (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (50%); Behzad Basirat Z (First Author), Main Researcher (50%)

Funding/Support: No financial support was provided.

Chemical warfare is one of the most brutal types of weapons of mass destruction, primarily using toxic agents to kill or incapacitate enemies [1]. Despite the Chemical Weapons Convention banning chemical weapons in 1993 due to the profound impact on human health and international security, some countries continue to produce them [2]. Chemical weapons are among the most inhumane weapons of warfare due to the severe acute and chronic health complications. The first large-scale use of chemical weapons after World War II occurred during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. Sulfur mustard (SM) is a potent alkylating agent that binds to proteins and nucleic acids, induces cellular necrosis, and leads to severe complications from inflammation to mutagenic and even carcinogenic outcomes. SM was originally synthesized in 1822 and was first employed in warfare by the German army in 1917 against both Canadian and French forces, and later by the British during the 1918 Hindenburg campaign. Several other nations, including Spain, Italy, the Soviet :union:, Japan, and Egypt, utilized sulfur mustard in military conflicts. Throughout the conflict (1980-1988), Iraq extensively used SM in many military operations. United Nations investigations have verified the use of SM through field assessments and clinical evaluations of exposed individuals. There are short- and long-term complications in various organ systems among survivors of SM exposure. The studies show that SM has different effects on the lung, skin, and eyes [3]. A notable example of chemical warfare occurred during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), where Iraq used sulfur mustard (SM). This potent alkylating agent has severe health effects, including chronic inflammation and long-term complications [4]. SM could cause mild conjunctivitis in the eye, skin, and pulmonary system, through delayed and severe chronic complications. Survivors may suffer from blindness, obstruction of the upper airways, chronic bronchitis, and bronchiolitis in the lung, and many known or unknown disorders [3]. The higher rate of health problems leads to an increase in the utilization of medical health services and medical costs among chemical warfare survivors and their families over time [4-9].

The medical expenses increase due to frequent need for hospitalizations, paraclinical, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation [5]. Recent studies on sulfur mustard have shown that it alkylates cellular components and induces the expression of a variety of inflammatory biomarkers that cause DNA damage and impair cellular function [10]. The immune system produces inflammatory factors to fight pathogens and facilitate healing. Still, persistent elevation of these markers leads to chronic inflammation, which is associated with diseases such as arthritis, asthma, autoimmune disorders, neurological diseases, diabetes, cancer, and conditions of aging [11], as well as mental disorders [6]. In terms of pathology, inflammation is one of the adaptive responses to numerous injuries caused by physical, chemical, and biological factors. The common signs of inflammation are related to tissues and cells responding to pathological injury induced by internal or external stimuli and damage-associated products and metabolites. The biomarkers provide important insights into the status and severity of inflammation, helping to predict patient outcomes, diagnose diseases, and monitor treatment [12]. This study examined the effects of sulfur mustard exposure on chronic inflammatory biomarkers, including pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, in SM-exposed survivors over time.

Inflammation is a complex biological phenomenon that resists a simple, universal definition. Depending on the context, it can be understood as a response to disturbance (such as infection), a process involving a series of defensive mechanisms aimed at eliminating the cause of that disturbance, or a state that may be pathological or protective. Each perspective highlights a different facet of inflammation. Renewed interest in the field has been driven by the recognition that inflammation is linked to nearly all human diseases. Moreover, emerging evidence shows that the cellular and molecular mediators involved in inflammation also participate in a wide array of biological functions, including tissue remodeling, metabolism, thermogenesis, and even nervous system activity. There are two types of recognition of inflammatory inducers: external and internal responses that trigger inflammation, which influence damage in retrospective and prospective modes. The prospective mode involves detecting potential threats before any tissue damage occurs. Pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) trigger inflammation. This allows the immune system to respond preemptively, even in the absence of actual pathogens, thereby limiting potential harm. Prospective recognition is advantageous because it enables early activation and potentially prevents tissue damage altogether. Similarly, other inflammatory inducers, such as toxins, can be recognized by their characteristic activities, enabling early (prospective) detection and response before significant harm is done to the host [13].

Chronic inflammation is a long-term state of continuous immune system activation, often due to persistent infections, autoimmune diseases, or chemical irritation, and can lead to various diseases [14]. Cytokines (including interleukins, interferons, tumor necrosis factors, and chemokines) play diverse roles in modulating immune responses, exerting both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects through intricate biochemical pathways and cellular interactions. Recent advances in immunology have led to a deeper understanding of the stimuli that trigger cytokine release, their mechanisms of action, and their downstream effects on immune regulation and tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, clinical research has increasingly implicated specific cytokines in the pathogenesis of various diseases, highlighting their potential as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets. When the immune system encounters pathogens, it secretes inflammatory factors in two stages: Pro-inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and BDNF) and anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13). Imbalance in the expression of these factors causes chronic inflammation [15]. Cytokine levels provide insights into the presence, severity, and progression of chronic diseases. Emerging evidence suggests that inflammation actively maintains the functional and structural integrity of tissues and organs. Understanding these physiological functions of inflammation could provide deeper insight into both the biology of health and the pathophysiology of disease. This study investigates the long-term effect of sulfur mustard on chronic inflammatory biomarkers in exposed survivors, including pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Cytokines

Cytokines are low-molecular-weight glycoproteins that play a central role in mediating immune cells and inflammation. Historically, cytokines have been classified into several subgroups based on their initially discovered functions, including interleukins (ILs), interferons, cytotoxic cytokines, colony-stimulating factors, chemokines, and other cytokines. Cytokines are often defined as interleukins produced predominantly by immune cells. These include cytokines associated with innate immunity—such as IL-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-6 —as well as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, which help regulate immune responses and maintain immune homeostasis. Cytokines are highly potent biological molecules that exert their effects at picogram concentrations. Cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 are small proteins and glycoproteins that are key biomarkers of chronic inflammation, reflecting sustained immune activity and underlying disease processes. These can be assessed in biological samples to monitor inflammatory status, track disease progression, and even inform treatment strategies for chronic conditions and diseases. However, their routine use is often constrained by technical and analytical limitations [16] (Table 1).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines

Pro-inflammatory cytokines include IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, BDNF, and GM-CSF. Sulfur mustard exposure has impacted each biomarker as follows:

Interleukin 1β

Interleukin 1β (IL-1β) is a key cytokine that promotes inflammation [17]. IL-1β, produced by activated macrophages, plays a fundamental role in the immune response to tissue injury and infection. IL-1β plays a role in resolving acute inflammation, and higher expression of IL-1β is associated with cell injury. When the balance of IL-1 level is disrupted, it may markedly contribute to the pathogenesis of both inflammatory disease and conditions that increase the risk of developing cancer. IL-1 is an attractive molecular target for treating a wide range of diseases, particularly autoinflammatory, autoimmune, infectious, metabolic syndrome, ischemic, and malignant tumors [18]. The effect of sulfur mustard on interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) has been of interest as an important inflammatory marker in many diseases [19]. Studies have shown that exposure to SM increases IL-1β levels and contributes to chronic inflammatory processes, which in turn increases the risk of neurological diseases (such as stroke, brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, and multiple sclerosis) and eye diseases (such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and macular degeneration) [17, 20-25]. This increased production of IL-1β is associated with the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways and the stimulation of immune responses, which can contribute to the development and progression of tissue damage and inflammation [26]. In clinical and preclinical studies, the toxic effects of SM on macrophages and other immune cells have been evaluated, and the results indicate that this substance can induce IL-1β expression through the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [27]. These processes, in turn, can lead to serious side effects and disease progression [28, 29]. Studies have shown that Sulfur mustard induces chronic inflammation by altering the expression of inflammatory cytokines, among which IL-1β, overexpressed, causes skin diseases [30].

Interleukin-6

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is another important cytokine involved in regulating immunity and inflammation [31]. Increased IL-6 in response to sulfur mustard is associated with chronic inflammation, which is implicated in psychiatric disorders. High levels of IL-6 are associated with increased risk of psychological stress/disorders, PTSD, impairment of neuronal function/synaptic resilience, which may play a role in the occurrence of psychotic disorders [32]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has a multifaceted impact, influencing inflammation, immune responses, and hematopoiesis. Increased levels of IL-6 can weaken the body's protection against infectious diseases. Moreover, IL-6 increases insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, suggesting a role in metabolic processes. It is involved in the development of plaque and atherosclerosis. The effects of IL-6 are both positive and negative, depending on the specific biological context and the physiological or pathological condition. An increase in IL-6 is associated with lymphoproliferative diseases, multiple myeloma, osteoporosis, and Alzheimer's disease, and can accelerate the premature aging process [33]. A cross-sectional study investigated the mental and physical health of 227 veterans exposed to sulfur mustard (SM) and 77 healthy individuals. The findings revealed that veterans’ exposure to SM exhibited higher levels of anxiety, insomnia, and psychiatric symptoms compared to the controls (p<0.05). Interestingly, levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were lower in the exposed group. In comparison, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels were higher (p<0.05), indicating a possible partial improvement in their mental and physical health [34]. Another study measured interleukin-6 in two groups: exposed individuals (60 patients with pulmonary symptoms and mild to severe complications; n=60) and healthy non-exposed individuals (n=30). The average interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration in patients was 0.76±0.30pg/ml, significantly higher than the control group's 0.34±0.12pg/ml (p=0.17) [35]. Several studies indicated a higher rate of mental health in SM exposed survivors and even their spouses, as well [36-43].

Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is recognized as a pro-inflammatory cytokine with diverse biological effects. TNF-α regulates inflammation, host defense, immunity/autoimmunity, apoptosis, carcinogenesis, and organ development. TNF is recognized as a key mediator of inflammatory and immune responses. TNF signals to immune cells that kill tumor cells. TNF plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). TNF-α acts as an arbitrator of the local tissue environment after injury. It can initiate apoptosis, regulate cell survival and proliferation, and tissue regeneration and remodeling. Excessive amounts of cytokines cause widespread inflammation that damages organs and tissues [44]. Sulfur Mustard is a blistering agent that damages the skin, eyes, and respiratory system. One of the main mechanisms of its toxicity is the induction of an inflammatory response in which TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha), a key pro-inflammatory cytokine, plays an important role [45]. Exposure to sulfur mustard can increase the expression and secretion of TNF-α from various cells, including keratinocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes [46]. This raises the risk of some chronic connective tissue disorders with endothelial dysfunction, fibrosis, cancer, and premature aging. This finding is consistent with previously published studies indicating that sulfur mustard (SM) acts as a carcinogen even after a single exposure, regardless of dose or duration [9]. Chemical warfare victims with eye and lung injuries experience significantly more psychological disorders, poor quality of life, and limitations in daily activities. This is largely determined by persistent lifelong symptoms caused by both irreversible and progressive health complications. Poor outcomes are further influenced by factors including the severity of the initial injury, the presence of comorbid conditions, and associated psychological disorders [36, 37, 39-43, 47].

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor

Among all neurotrophic factors, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a crucial role in promoting neurogenesis, neuronal survival and growth, modulates neurotransmission, and participates in neuronal plasticity (essential for learning and memory). BDNF regulates energy metabolism and glucose metabolism and helps prevent β-cell exhaustion. Decreasing the levels of BDNF commonly associates with neurodegenerative diseases (such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis). BDNF also helps prevent and manage diabetes mellitus [48]. The exposure to sulfur SM has been shown to adversely affect BDNF levels, which are crucial for neuronal survival, growth, and function [49]. Limited studies have also shown that Sulfur mustard can induce neuro-inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to decreased BDNF expression [50, 51]. This reduction in BDNF may impair neuroplasticity and cognitive functions, highlighting the potential long-term neurological consequences of sulfur mustard exposure [52]. In only one study it has been showed that the level of BDNF in serum were elevated [34].

When individuals are exposed to sulfur mustard, the resultant inflammation and oxidative stress can disrupt the normal expression of BDNF [34]. Survivors exposed to sulfur mustard exhibit varying levels of this biomarker, and this imbalance may lead to psychiatric disorders and central nervous system diseases [53]. This disruption can result in lower levels of BDNF in the brain, leading to several potential consequences: First, can activate inflammatory pathways in the central nervous system. This inflammation can create an unfavorable environment for neurons and adversely affect BDNF signaling [54]. Second, reduced BDNF levels are associated with impaired cognitive functions, such as learning and memory. Individuals exposed to sulfur mustard may experience difficulties in these areas due to lower neuroplasticity [55]. It may have long-lasting implications, potentially leading to chronic neurological issues, including neurodegenerative diseases or cognitive decline [56]. Moreover, BDNF plays a significant role in the aging process [57]. Overall, the impact of sulfur mustard on BDNF levels underscores the need for further research to understand its effects on brain health and the mechanisms involved.

Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a growth factor that stimulates myeloid progenitor cells. Produced by various cells (T cells, phagocytes, etc.), GM-CSF enhances immune responses by generation of myeloid cell subsets including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells in response to stress, infections, and cancers and activating immune cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), and plays a critical role in regulating myeloid cell host defense [58]. The DCs, along with macrophages and monocytes, are antigen-presenting cells (APCs) whose function is enhanced by GM-CSF. GM-CSF works alongside other inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8) in regulating immunity and inflammation [59]. GM-CSF abnormal level (both low and high) can worsen autoimmune diseases and inflammation, weaken immunity, and impair wound healing. Elevated GM-CSF has been shown to contribute to inflammation in inflammatory arthritis, osteoarthritis, colitis, asthma, obesity, and COVID-19 [60], as well as accelerate aging [61]. The specific dangers depend on the extent and cause of the imbalance [62]. A study investigating the role of cytokines in sulfur mustard-induced pulmonary fibrosis examined bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from 18 sulfur mustard-exposed veterans with pulmonary fibrosis (PF) and 18 control subjects. Significantly higher levels of G-CSF and GM-CSF were found in the BAL fluid of exposed patients compared with controls. IL-8 levels were also significantly elevated. In addition, IL-8 and G-CSF levels correlated with neutrophil counts, while GM-CSF levels correlated with eosinophil counts in the BAL fluid of SM-exposed patients. The findings suggest that neutrophilic alveolitis, eosinophilia, and increased IL-8, G-CSF, and GM-CSF in BAL fluid are associated with the development of fibrosis in sulfur mustard victims [60]. In a cohort study in Sardasht, Iran, the effect of sulfur SM on GM-CSF levels was investigated in two groups of exposed (n=369) and unexposed (n=125) after 20 years. This study reported that serum GM-CSF levels were not significantly different between exposed and unexposed subjects. However, a positive correlation was observed between GM-CSF and eosinophil counts in the exposed group. Furthermore, this study found no significant association between GM-CSF levels and pulmonary function parameters [61].

Anti-inflammatory cytokines

Interleukin-4

Like many cytokines, Interleukin-4 (IL-4) can affect numerous target cells in several ways. IL-4 plays a significant role in the development of effector T-cell responses, regulating antibody production, hematopoiesis, and inflammation. IL-4 is a cytokine that plays a crucial role in the immune system, primarily involved in promoting the differentiation of naive T cells into T-helper 2 (Th2) cells [63]. IL-4 is also essential for the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) and the activation of mast cells and eosinophils, which are key players in allergic responses and asthma. Overproduction of IL-4 causes hyperactivation of lymphocytes, elevated IgE levels, and autoimmunity [64]. Following exposure to sulfur mustard, there is evidence of increased IL-4 levels due to its pro-inflammatory effects [65, 66]. Recent studies have highlighted the role of IL-4 in mediating the Th2 response in models of chemical exposure, including sulfur mustard [67]. This increased IL-4 production can contribute to a broader inflammatory response, exacerbating tissue injury and promoting airway hyper-responsivity [68]. Understanding the modulation of IL-4 following sulfur mustard exposure is essential for developing therapeutic strategies to manage inflammation and related respiratory conditions [69]. Veterans exposed to sulfur mustard have high levels of IL-4. This substance increases IgE production (an allergy-related antibody), leading to severe inflammation in the lungs and other tissues, ultimately causing tissue damage [70].

Interleukin-10

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is well-known for its potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects and is produced by T helper 2 cells. IL-10 is now known to be produced by various myeloid- and lymphoid-derived immune cells participating in both innate and adaptive immunity. IL-10 plays an essential role in modulating inflammation and maintaining cellular homeostasis. It acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine that protects against an uncontrolled immune response and has immune-stimulating functions. IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine that inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Excess IL-10 can indirectly damage various tissues in the body by suppressing the immune system, promoting the growth of cancer cells, and impairing wound healing [71]. Recent researches suggest that while IL-10 is increased following sulfur mustard injury, an imbalance in favor of inflammation can reduce the protective effects of IL-10, leading to long-term tissue damage and altered immune responses [72, 73]. In one study, the levels of the cytokines TNF-α in tears, and IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-6, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and FasL in the serum of 128 SM-exposed veterans with severe ocular injury were compared with those of 31 healthy controls. The results showed that in SM-exposed veterans, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), decreased tear breakup time (TBUT<10 seconds), and conjunctival, limbal, and corneal abnormalities were more common. The severity of ocular injury was mild in 14.8%, moderate in 24.2%, and severe in 60.9%. Serum levels of IL-1α and FasL were significantly higher in veterans, and serum and tear levels of TNF-α were significantly lower than in controls (p<0.001). Serum levels of FasL were significantly higher in cases with severe ocular injury than in controls (p=0.03). There was no significant difference in serum levels of IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-1α/IL-1Ra, and IL-6 between the two groups. Finally, increased serum levels of IL-1α and FasL may contribute to the development of ocular surface abnormalities in patients exposed to SM, and the decrease in TNF-α in tears is likely due to reduced serum levels of this cytokine [19]. A similar study indicated that the incidence rate of cancer was significantly increased in SM exposed survivors. The incidence rate ratio of cancer for SM exposure was 2 times higher than that of the general population. This study suggests carcinogenesis of SM following acute exposure to SM in the victims after 20 years of exposure [9].

Interleukin-13

Interleukin-13 (IL-13) is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that regulates IgE synthesis, goblet cell hyperplasia, and mucus hypersecretion and causes airway hyper-responsivity. IL-13 is an important mediator for allergic inflammation, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. IL-13 has effects on immune cells. It is suspected that IL-13 is the core mediator of the physiologic changes made by allergic inflammation in many tissues. IL-13 is involved in various processes, including airway remodeling, fibrosis, and mucus production regulation. High levels of IL-13 indicate that the immune system is overactive. This could be a response to an ongoing infection or disease that the body is trying to fight off [74]. Following exposure to sulfur mustard, IL-13 levels may be increased or decreased, with elevated levels associated with asthma, allergies, fibrosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. The decreased level of IL-13 is associated with increased risk of infection and impaired wound healing [75]. Recent studies have shown that IL-13 is often upregulated in response to airway irritants and is linked to the pathophysiology of asthma [76]. In the context of sulfur mustard exposure, increased IL-13 levels can exacerbate bronchoconstriction and contribute to long-term respiratory sequelae [77]. Treatment targeting IL-13 could mitigate the adverse effects associated with sulfur mustard-induced inflammation.

Table 1. Impact of sulfur mustard on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine

Conclusion

Sulfur mustard leads to significant changes in inflammatory markers, including pro-inflammatory (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory cytokines. These changes indicate activation of the innate immune system and initiation of a severe inflammatory response. SM exposure activates inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB pathway, which ultimately increases the production of additional pro-inflammatory cytokines. These changes appear to be a regulatory mechanism that controls the initial severe inflammatory response and prevents further tissue damage. Overall, SM causes a significant imbalance in both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory biomarkers. An initial and dominant increase in pro-inflammatory biomarkers causes widespread tissue damage. While the subsequent increase in anti-inflammatory biomarkers serves as a compensatory mechanism, it is insufficient to mitigate the damaging effects of inflammation alone. This imbalance in biomarkers is one of the important factors in the development of long-term complications after sulfur mustard exposure. These complications include chronic respiratory, skin, and eye diseases, as well as an increased risk of cancer. Numerous factors, including age, sex, adiposity status, and overall inflammatory state, can affect circulating cytokine levels. Therefore, it should be considered that, in addition to SM, cytokines may also be influenced by some of these factors. Future studies will focus on further developing the predictive biomarker modeling framework to extract predictive biomarkers from complex data. Additionally, combining biomarkers from different sources (imaging, molecular, clinical) can improve the accuracy of SM outcome predictions.

Acknowledgments: Finally, we would like to express our deepest gratitude to the esteemed directors of the Veterans Engineering and Medical Sciences Research Center, Dr. Abbas Vali and Dr. Zohreh Ganjparvar, for their moral support and participation in the present research process.

Ethical Permissions: Not needed.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have not reported any conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Mousavi B (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist (50%); Behzad Basirat Z (First Author), Main Researcher (50%)

Funding/Support: No financial support was provided.

Keywords:

References

1. Kozlov MY, Ashvits IV. History of the use of chemical weapons for military purposes and the possibility of their current use. Sci Bull Omsk State Med Univ. 2024;4(1):75-86. [Link] [DOI:10.61634/2782-3024-2024-13-75-86]

2. Butera E, Zammataro A, Pappalardo A, Trusso Sfrazzetto G. Supramolecular sensing of chemical warfare agents. Chempluschem. 2021;86(4):681-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cplu.202100071]

3. Amini H, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Mousavi B, Alam Beladi SN, Soroush MR, Abolghasemi J, et al. Long-term health outcomes among survivors exposed to sulfur mustard in Iran. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028894. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28894]

4. Taebi G, Soroush M, Modirian E, Khateri S, Mousavi B, Ganjparvar Z, et al. Human costs of Iraq's chemical war against Iran; An epidemiological study. Iran J War Public Health. 2015;7(2):115-21. [Persian] [Link]

5. Mehdizadeh P, Ghanei M, Pourreza A, Akbari-Sari A, Mousavi B, Darroudi R. Healthcare utilization and expenditures among Iranian chemical warfare survivors exposed to sulfur mustard. Arch Iran Med. 2022;25(4):241-9. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/aim.2022.40]

6. Mousavi B, Asgari M, Soroush M, Montazeri A. Psychiatric disorder and quality of life in female survivors of the Iran-Iraq war; Three decades after injuries. Iran J War Public Health. 2021;13(1):41-7. [Link]

7. Soroush MR, Ganjparvar Z, Mousavi B. Human casualties and war: Results of a national epidemiologic survey in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23(4 Suppl 1):S33-7. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/aim.2020.s7]

8. Mousavi B, Maftoon F, Soroush M, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R. Health care utilization and expenditure in war survivors. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23(4 Suppl 1):S9-15. [Link] [DOI:10.34172/aim.2020.s3]

9. Zafarghandi MR, Soroush MR, Mahmoodi M, Naieni KH, Ardalan A, Dolatyari A, et al. Incidence of cancer in Iranian sulfur mustard exposed veterans: A long-term follow-up cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(1):99-105. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10552-012-0094-8]

10. Kehe K, Balszuweit F, Steinritz D, Thiermann H. Molecular toxicology of sulfur mustard-induced cutaneous inflammation and blistering. Toxicology. 2009;263(1):12-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.tox.2009.01.019]

11. Soroush M, Akhavizadegan H, Mousavi B. Health problems in survivors exposed to sulfur mustard with severe respiratory complications. Iran J War Public Health. 2020;12(2):109-14. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijwph.12.2.109]

12. Morcuende A, Navarrete F, Nieto E, Manzanares J, Femenía T. Inflammatory biomarkers in addictive disorders. Biomolecules. 2021;11(12):1824. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/biom11121824]

13. Medzhitov R. The spectrum of inflammatory responses. Science. 2021;374(6571):1070-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1126/science.abi5200]

14. Danforth DN. The role of chronic inflammation in the development of breast cancer. Cancers. 2021;13(15):3918. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/cancers13153918]

15. Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, Gaudin C, Peyrot C, Vellas B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(12):877-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.009]

16. Monastero RN, Pentyala S. Cytokines as biomarkers and their respective clinical cutoff levels. Int J Inflam. 2017;2017:4309485. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2017/4309485]

17. Yaraee R, Ghazanfari T, Ebtekar M, Ardestani SK, Rezaei A, Kariminia A, et al. Alterations in serum levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1alpha, IL-1beta and IL-1Ra) 20 years after sulfur mustard exposure: Sardasht-Iran cohort study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(13-14):1466-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2009.09.001]

18. Jayaraman P, Sada-Ovalle I, Nishimura T, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, Remold HG, et al. IL-1β promotes antimicrobial immunity in macrophages by regulating TNFR signaling and caspase-3 activation. J Immunol. 2013;190(8):4196-204. [Link] [DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1202688]

19. Ghasemi H, Javadi MA, Ardestani SK, Mahmoudi M, Pourfarzam S, Mahdavi MRV, et al. Alteration in inflammatory mediators in seriously eye-injured war veterans, long-term after sulfur mustard exposure. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;80:105897. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105897]

20. Mishra N, Agarwal R. Research models of sulfur mustard- and nitrogen mustard-induced ocular injuries and potential therapeutics. Exp Eye Res. 2022;223:109209. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.exer.2022.109209]

21. Tapak M, Sadeghi S, Ghazanfari T, Mossafa N, Mirsanei SZ, Masiha Hashemi SM. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy mitigates acute and chronic lung damages of sulfur mustard analog exposure. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;23(5):563-77. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/ijaai.v23i5.16751]

22. Cruz-Hernandez A, Mendoza RP, Nguyen K, Harder A, Evans CM, Bauer AK, et al. Mast cells promote nitrogen mustard-mediated toxicity in the lung associated with proinflammatory cytokine and bioactive lipid mediator production. Toxicol Sci. 2021;184(1):127-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfab107]

23. Hassanpour H, Mojtahed M, Fallah AA, Najafi-Chaleshtori S. Effect of mustard analogs on cytokine profile in rodents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143(Pt 2):113465. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113465]

24. Panahi Y, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Jamalkandi SA, Ghanei M, Pedone C, Nikravanfard N, et al. Immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sulfur mustard induced airway injuries: Implications for immunotherapeutic interventions. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(20):2975-96. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1381612822666160307150818]

25. Salpea KD, Maubaret CG, Kathagen A, Ken-Dror G, Gilroy DW, Humphries SE. The effect of pro-inflammatory conditioning and/or high glucose on telomere shortening of aging fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73756. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0073756]

26. Sierawska O, Małkowska P, Taskin C, Hrynkiewicz R, Mertowska P, Grywalska E, et al. Innate immune system response to burn damage-focus on cytokine alteration. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):716. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijms23020716]

27. Haines DD, Cowan FM, Tosaki A. Evolving strategies for use of phytochemicals in prevention and long-term management of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(11):6176. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijms25116176]

28. Kempf CL, Song JH, Sammani S, Bermudez T, Reyes Hernon V, Tang L, et al. TLR4 ligation by eNAMPT, a novel DAMP, is essential to sulfur mustard-induced inflammatory lung injury and fibrosis. Eur J Respir Med. 2024;6(1):389-97. [Link] [DOI:10.31488/EJRM.141]

29. Amiri M, Jafari M, Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, Davoodi SM. Atopic dermatitis-associated protein interaction network lead to new insights in chronic sulfur mustard skin lesion mechanisms. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2013;10(5):449-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1586/14789450.2013.841548]

30. Khaheshi I, Keshavarz S, Imani Fooladi AA, Ebrahimi M, Yazdani S, Panahi Y, et al. Loss of expression of TGF-βs and their receptors in chronic skin lesions induced by sulfur mustard as compared with chronic contact dermatitis patients. BMC Dermatol. 2011;11:2. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-5945-11-2]

31. Hirano T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int Immunol. 2021;33(3):127-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/intimm/dxaa078]

32. Angelini DJ, Dorsey RM, Willis KL, Hong C, Moyer RA, Oyler J, et al. Chemical warfare agent and biological toxin-induced pulmonary toxicity: could stem cells provide potential therapies? Inhal Toxicol. 2013;25(1):37-62. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/08958378.2012.750406]

33. Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:245-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245]

34. Ghaedi GH, Nasiri L, Hassanpour H, Mehdi Naghizadeh M, Abdollahzadeh A, Ghazanfari T. Evaluation of serum BDNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels alongside assessing mental health and life satisfaction in sulfur mustard-chemical veterans. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143(Pt 2):113479. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113479]

35. Panahi Y, Ghanei M, Vahedi E, Ghazvini A, Parvin S, Madanchi N, et al. Effect of recombinant human IFNγ in the treatment of chronic pulmonary complications due to sulfur mustard intoxication. J Immunotoxicol. 2014;11(1):72-7. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/1547691X.2013.797525]

36. Ghaedi G, Ghasemi H, Mousavi B, Soroush MR, Rahnama P, Jafari F, et al. Impact of psychological problems in chemical warfare survivors with severe ophthalmologic complication, a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:36. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-10-36]

37. Jafari F, Guitynavard F, Soroush M, Mousavi B. Quality of life in chemical war victims with sever pulmonary damage. Iran J War Public Health. 2012;4(1):46-52. [Persian] [Link]

38. Jafari F, Moien L, Soroush M, Mousavi B. Quality of life in chemical warfare victims with ophthalmic damage's spouses. Iran J War Public Health. 2011;3(3):8-12. [Persian] [Link]

39. Assari S, Lankarani MM, Montazeri A, Soroush MR, Mousavi B. Are generic and disease-specific health related quality of life correlated? The case of chronic lung disease due to sulfur mustard. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14(5):285-90. [Link]

40. Mousavi B, Ganjparvar Z, Soroush M, Vadieh S. Health problems among chemical warfare survivors with ophthalmologic injuries. Iran J War Public Health. 2009;1(2):36-47. [Persian] [Link]

41. Mousavi B, Soroush MR, Montazeri A. Quality of life in chemical warfare survivors with ophthalmologic injuries: The first results form Iran Chemical Warfare Victims Health Assessment Study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:2. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-7-2]

42. Mousavi B, Khateri S, Soroush MR, Amini R, Masumi M, Montazeri A. Comparing quality of life between survivors of chemical warfare exposure and conventional weapons: Results of a national study from Iran. J Med CBR Def. 2011;8. [Link]

43. Assari S, Soroush MR, Khoddami Vishteh HR, Mousavi B, Ghanei M, Karbalaeiesmaeil S. Marital relationship and its associated factors in veterans exposed to high dose chemical warfare agents. J Fam Reprod Health. 2008;2(2):69-74. [Link]

44. Wang T, He C. TNF-α and IL-6: The link between immune and bone system. Curr Drug Targets. 2020;21(3):213-27. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1389450120666190821161259]

45. Gonzalez Caldito N. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the central nervous system: A focus on autoimmune disorders. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1213448. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1213448]

46. Wormser U, Brodsky B, Proscura E, Foley JF, Jones T, Nyska A. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in sulfur mustard-induced skin lesion; Effect of topical iodine. Arch Toxicol. 2005;79(11):660-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00204-005-0681-5]

47. Mehdizadeh S, Salaree M, Ebadi A, Aslan J, Jafari N. Health-related quality of life in chemical warfare victims with bronchiolitis obliterans. Iran J Nurs Res. 2011;6(21):6-14. [Persian] [Link]

48. Dadkhah M, Baziar M, Rezaei N. The regulatory role of BDNF in neuroimmune axis function and neuroinflammation induced by chronic stress: A new therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative disorders. Cytokine. 2024;174:156477. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cyto.2023.156477]

49. Smith KJ, Hurst CG, Moeller RB, Skelton HG, Sidell FR. Sulfur mustard: Its continuing threat as a chemical warfare agent, the cutaneous lesions induced, progress in understanding its mechanism of action, its long-term health effects, and new developments for protection and therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 1):765-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0190-9622(95)91457-9]

50. Romano JA, Lukey BJ, Salem H, editors. Chemical warfare, chemical terrorism, and traumatic stress responses: An assessment of psychological impact. In: Chemical warfare agents: Chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and therapeutics. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. [Link]

51. Golime R, Singh N. Chapter 29-Molecular interactions of chemical warfare agents with biological systems. In: Sensing of deadly toxic chemical warfare agents, nerve agent simulants, and their toxicological aspects. New York: Elsevier; 2023. p. 687-710. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-323-90553-4.00028-7]

52. Boulle F, Van Den Hove DL, Jakob SB, Rutten BP, Hamon M, Van Os J, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the BDNF gene: Implications for psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(6):584-96. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/mp.2011.107]

53. Nasiri L, Hassanpour H, Ardestani SK, Ghazanfari T, Jamali D, Faghihzadeh E, et al. Health assessment of sulfur mustard-chemical veterans with various respiratory diseases: The result of a comparative analysis of biological health scores (BHS) through 50 biomarkers. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;145:113767. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113767]

54. Lima Giacobbo B, Doorduin J, Klein HC, Dierckx RAJO, Bromberg E, De Vries EFJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in brain disorders: Focus on neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(5):3295-312. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12035-018-1283-6]

55. Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Tsutsumimoto K, Anan Y, et al. A large, cross-sectional observational study of serum BDNF, cognitive function, and mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:69. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00069]

56. Phillips C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and physical activity: Making the neuroplastic connection. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:7260130. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2017/7260130]

57. Budni J, Bellettini-Santos T, Mina F, Garcez ML, Zugno AI. The involvement of BDNF, NGF and GDNF in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Aging Dis. 2015;6(5):331-41. [Link] [DOI:10.14336/AD.2015.0825]

58. Bhattacharya P, Thiruppathi M, Elshabrawy HA, Alharshawi K, Kumar P, Prabhakar BS. GM-CSF: An immune modulatory cytokine that can suppress autoimmunity. Cytokine. 2015;75(2):261-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.030]

59. Hallsworth MP, Soh CP, Lane SJ, Arm JP, Lee TH. Selective enhancement of GM-CSF, TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta and IL-8 production by monocytes and macrophages of asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 1994;7(6):1096-102. [Link] [DOI:10.1183/09031936.94.07061096]

60. Emad A, Emad Y. Increased granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) levels in BAL fluid from patients with sulfur mustard gas-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Aerosol Med. 2007;20(3):352-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/jam.2007.0590]

61. Amiri S, Ghazanfari T, Yaraee R, Salimi H, Ebtekar M, Shams J, et al. Serum levels of GM-CSF 20 years after sulfur mustard exposure: Sardasht-Iran Cohort Study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(13-14):1499-503. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2009.08.023]

62. Shiomi A, Usui T, Mimori T. GM-CSF as a therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases. Inflamm Regen. 2016;36:8. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s41232-016-0014-5]

63. Keegan AD, Leonard WJ, Zhu J. Recent advances in understanding the role of IL-4 signaling. Fac Rev. 2021;10:71. [Link] [DOI:10.12703/r/10-71]

64. Matucci A, Vultaggio A, Maggi E, Kasujee I. Is IgE or eosinophils the key player in allergic asthma pathogenesis? Are we asking the right question?. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):113. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12931-018-0813-0]

65. Moin A, Khamesipour A, Hassan ZM, Ebtekar M, Davoudi SM, Vaez-Mahdavi MR, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines among individuals with skin findings long-term after sulfur mustard exposure: Sardasht-Iran Cohort Study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17(3):986-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2012.12.022]

66. Khazdair MR, Boskabady MH. Possible treatment approaches of sulfur mustard-induced lung disorders, experimental and clinical evidence, an updated review. Front Med. 2022;9:791914. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2022.791914]

67. Panahi Y, Ghanei M, Hassani S, Sahebkar A. TGF-β and Th17 cells related injuries in patients with sulfur mustard exposure. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(4):3037-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jcp.26077]

68. Le Gros G, Ben-Sasson SZ, Seder R, Finkelman FD, Paul WE. Generation of interleukin 4 (IL-4)-producing cells in vivo and in vitro: IL-2 and IL-4 are required for in vitro generation of IL-4-producing cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172(3):921-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1084/jem.172.3.921]

69. Panahi Y, Ghanei M, Bashiri S, Hajihashemi A, Sahebkar A. Short-term curcuminoid supplementation for chronic pulmonary complications due to sulfur mustard intoxication: Positive results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Drug Res. 2015;65(11):567-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1055/s-0034-1389986]

70. Pourfarzam S, Ardestani SK, Jamali T, Ghazanfari H, Naghizadeh MM, Faghihzadeh S, et al. Distinct inflammatory profiles in mustard lung: A study of sulfur mustard-exposed patients with serious pulmonary complications. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;146:113832. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113832]

71. Mosser DM, Zhang X. Interleukin-10: New perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:205-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00706.x]

72. Ghazanfari Z, Ghazanfari T, Kermani-Jalilvand A, Yaraee R, Vaez-Mahdavi MR, Foroutan A, et al. Association of physical activity and IL-10 levels 20 years after sulfur mustard exposure: Sardasht-Iran cohort study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(13-14):1504-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2009.08.025]

73. Hassanpour M, Hajihassani F, Abdollahpourasl M, Cheraghi O, Aghamohamadzade N, Rahbargazi R, et al. Pathophysiological effects of sulfur mustard on skin and its current treatments: Possible application of phytochemicals. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2021;24(1):3-19. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1386207323666200717150414]

74. De Vries JE. The role of IL-13 and its receptor in allergy and inflammatory responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(2):165-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70080-6]

75. Nourani MR, Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini H, Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, Imani Fooladi AA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of acute exposure to sulfur mustard: A systematic review. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2017;37(2):200-16. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10799893.2016.1212374]

76. Seyfizadeh N, Seyfizadeh N, Gharibi T, Babaloo Z. Interleukin-13 as an important cytokine: A review on its roles in some human diseases. ACTA MICROBIOLOGICA ET IMMUNOLOGICA HUNGARICA. 2015;62(4):341-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1556/030.62.2015.4.2]

77. Khazdair MR, Boskabady MH, Ghorani V. Respiratory effects of sulfur mustard exposure, similarities and differences with asthma and COPD. Inhal Toxicol. 2015;27(14):731-44. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/08958378.2015.1114056]