Volume 16, Issue 4 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(4): 355-361 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/10/5 | Accepted: 2024/11/23 | Published: 2024/11/29

Received: 2024/10/5 | Accepted: 2024/11/23 | Published: 2024/11/29

How to cite this article

Jaafar S, Al-Jebouri M, Mousa A, Bachai G. Disaster Preparedness and Core Competencies in Iraqi Nurses. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (4) :355-361

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1515-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1515-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Adult Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Al-Muthanna, Samawa, Iraq

2- Department of Adult Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

3- Department of Adult Nursing, Al-Hussein Teaching Hospital, Samawa, Iraq

2- Department of Adult Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

3- Department of Adult Nursing, Al-Hussein Teaching Hospital, Samawa, Iraq

Full-Text (HTML) (1117 Views)

Introduction

Disasters are natural, artificial, and technological, need rapid response, are challenging to prepare, and increase the negative impact in the future related to climate changes, displacement, conflicts, and public health emergencies [1]. There is a lack of nurses' preparedness and core competence, and there is a gap in legislation, education programs, and awareness of the pre-disaster. The nurse's role is under development, and there is no clear coverage for education programs and training in many regions [2-4]. Long-standing effects following disasters are remarkable problems [5]. People may suffer from socioeconomic [6], behavioral, biological [7], and psychological problems, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, injuries, and disabilities, and nurses need to be competent in dealing with such cases [8].

Disaster preparedness among nurses is crucial in response, recovery, and evaluation [9]. The role of the nurses in disaster goes beyond routine daily work [10]. In some countries with a shortage of medical doctors, nurses lead disaster programs through response and rehabilitation [11]. Despite competency-based education expanding worldwide, some areas still depend on evaluation trainees for the nurses' activities and performances. Competency is well defined in the literature as the ability of nurses to apply tasks and activities with perfect performance, and these activities must be measurable and observable [12-14]. Competencies of disasters include the use of professional skills such as critical thinking, specific skills, general skills, technical skills, and communication and coordination of operations [3, 12]. Due to their vital role, nurses' preparedness is increasingly significant in disaster-prone areas and specific geographical regions [15, 16].

The specific disaster competencies expected of nurses should encompass the four main phases of disaster management: preparedness, response, and recovery. During the preparedness phase, planning, continuous education and training, assessment, and evaluation of activities related to disaster management are carried out [17]. After preparedness, the mitigation phase begins, during which a comprehensive plan is developed to identify risks, formulate strategies to address them and implement interventions to strengthen resilience against disasters. In the response phase, nurses are activated alongside other personnel, focusing on saving lives, reducing infrastructure damage, and supporting survivors by providing basic needs. Finally, the recovery phase is centered on restoring normal levels of social functioning [18].

In addition to these phases, effective disaster management requires a multidisciplinary approach where nurses collaborate with emergency responders, government agencies, and community organizations to ensure a coordinated and efficient response. Nurses play a crucial role in direct patient care and disaster risk communication, public education, and advocacy for improved disaster preparedness policies [19]. Their ability to assess community needs, provide psychological support, and assist in rebuilding healthcare services makes them indispensable in disaster recovery efforts. As disasters become more frequent and complex due to climate change and global health threats, investing in nursing education, simulation-based training, and policy development is essential to enhancing resilience and ensuring a more effective disaster response system [13, 19].

The cornerstone in disaster management is that nurses should be well-trained and prepared to face the effects of the disaster. The training includes new learning and training strategies that can enhance nurses' psychological preparedness during the crisis and their abilities to care for themselves and others [20, 21].

Despite increasing awareness of the importance of possessing the necessary competencies to provide care and respond to disasters and public health emergencies, the definitions of these competencies remain ambiguous; they have not been formally validated, and nurses remain uncertain about their roles in such situations. This uncertainty can lead to hesitation and inefficiency in disaster response, ultimately affecting the quality of care provided to affected individuals [22].

Despite receiving education and training in disaster management, including general knowledge of disasters, the proper use of protective equipment, trauma care, biological information, bioterrorism management, the control and management of infectious diseases in disaster-affected areas, the implementation of disaster policies and plans, the role of hospitals during disasters, and their own roles in emergencies, nurses still lack sufficient knowledge [17-21]. This knowledge gap is particularly concerning as it directly impacts their ability to respond effectively in high-pressure situations. Furthermore, many nurses do not receive adequate hands-on experience or simulation-based training, crucial for developing confidence and competence in real-world disaster scenarios [17].

This lack of knowledge is further compounded by a deficiency in practical skills, despite nurses recognizing that a diverse skill set is essential for effectively responding to life-threatening situations [21, 22]. Skills such as rapid triage, emergency wound care, crisis communication, and psychological first aid are often insufficiently covered in training programs, leaving nurses feeling underprepared. Moreover, disaster settings frequently require adaptability, leadership, and decision-making skills under extreme conditions—capabilities many nurses feel inadequately trained for [17].

As a result, the lack of knowledge and skills negatively impacts nurses' confidence in their ability to provide disaster-related patient care and fulfill their expected roles and responsibilities. Many nurses experience anxiety and self-doubt when placed in emergency situations, fearing that they may not be able to act effectively [23]. Additionally, individuals are implicitly expected to suddenly become "strong nurses" when faced with disaster situations, despite insufficient preparation. This unrealistic expectation places significant psychological pressure on nurses, potentially leading to burnout, emotional distress, and reduced job satisfaction over time [17].

To address these challenges, it is essential to develop standardized and validated competency frameworks, ensuring that nurses receive structured education and hands-on training in disaster preparedness and response [17, 22]. Strengthening nursing curricula, increasing access to practical disaster simulations, and integrating psychological resilience training can help nurses feel more confident and capable in crisis situations. Investing in the continuous professional development of nurses and equipping them with the necessary skills and knowledge will enhance disaster response efforts and improve overall public health resilience in emergencies [23].

In Iraq, where the largest mass gatherings occur [24], disaster preparedness and nurse training are necessary to face future challenges [25]. Although experience with previous people displacement related to terrorist impact, wars for decades, and geographical location near the countries are active with earthquakes [26, 27], Iraq still follows traditional responses with no emergency preparedness in the last years [28, 29]. Nevertheless, there is no survey evidence of the level of readiness and core competence perception among nurses, only knowledge and practice assessment [29]. Therefore, the need to evaluate nurses' preparedness and core competence is a part of facing potential future risks and describing the level of disaster preparedness.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February 22 to August 15, 2024, in four teaching hospitals (Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Al-Yarmouk Teaching Hospital, Al-Kindi Teaching Hospital, and Al-Hussein Teaching Hospital) and three general hospitals (Al-Rumaitha Hospital, Alkhudier Hospital, and Al-Warkaa Hospital) in the mid-and south of Iraq. The sample size calculation was done using a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. Based on this method, the survey targeted 380 nurses. Only 374 nurses completed the survey. The nurses who were invited have completed at least one year of experience. Furthermore, nurses who work in different fields, such as the ER, ICU, CCU, and med-surg. units, OR, infection control, continuous education, and hemodialysis. A convenience method was used to select the study sample.

Instrument

The demographic characteristics (age, gender, job description, area of expertise, years of experience, and hospital type) were recorded in the first part. The second part had nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness, including using a visual scale to ask questions about how they feel prepared for disasters. The answers include (0) having no preparedness and (10) being fully prepared for disasters. The confirmed Turkish scale of "nurses' perception of disaster core competence (NPDCC)”, developed by Celik & Nahcivan [30, 31] (Cronbach's alpha=0.96), also used by Taskiran & Baykal [3], the scale has 45 items in five domain includes, critical thinking (items 1-4), specific assessment skills (items 5-10), general assessment skills (items 11-23), technical skills (items 24-37), and communication skills (items 38-45). The scale scored based on a 5-Likert scale (“this needs to be taught to” I can do and teach it 5). The minimum to maximum score range is between 45 and 225. Lower scores mean lower perception and core competence; A high score means better perception and core competence. The corresponding authors get permission to use the tool from the original authors via e-mail. The survey was conducted on 380 nurses.

Procedure

The authors obtained permission from the scientific committee in the College of Nursing at the University of Al-Muthanna. The consent forms were distributed to the participants, who had the right to withdraw without penalty. The current study's data collection involved a face-to-face method. The three authors were recruited to collect the data; Two were collected from Baghdad City hospitals, and another author collected the data from the Al-Muthanna governorate hospitals. An anonymous survey was used to collect the data from the participants. Each participant took 5-15 minutes to complete the survey. The questionnaires were distributed at rest to avoid working interruptions in the emergency, operation room, and intensive care unit.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS 20 and Microsoft Excel 2010 by an independent two-sample t-test analysis of variance (ANOVA) at p<0.05 significant level.

Findings

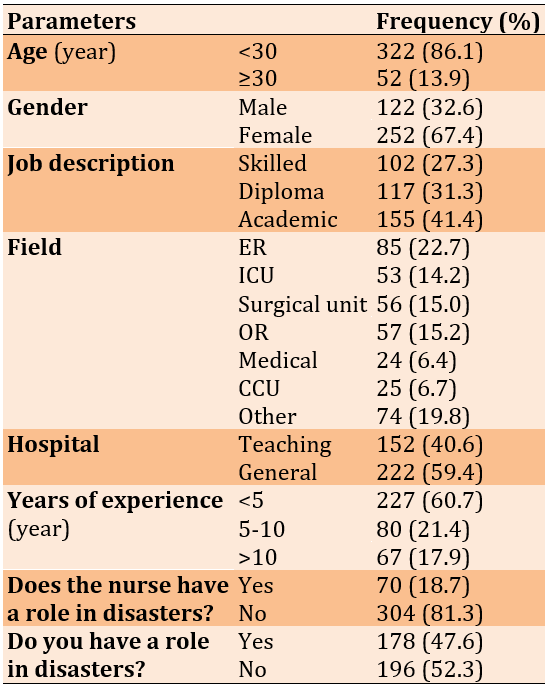

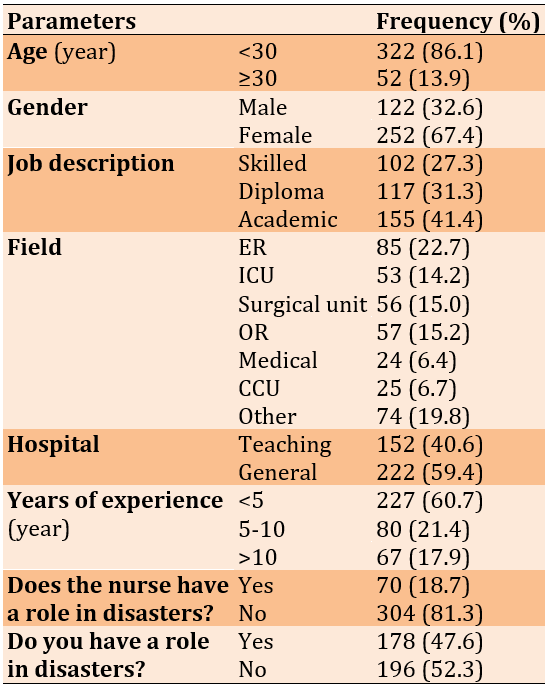

The mean age of 374 nurses was 28.2±5.4 years. More than half of nurses were female (67.4%). Their job description was an academic nurse; most worked in the emergency unit (22.7%). The mean of years of experience is 5.75 years, and the standard deviation is 5.30 years. More than half of the study participants (59.4%) were affiliated with the general (public) hospital. Most participants (81.3%) believed that the nurses have no role in the disaster, and half felt they have no role in the disaster (52.3%; Table 1).

Table1. The frequency of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (n=374)

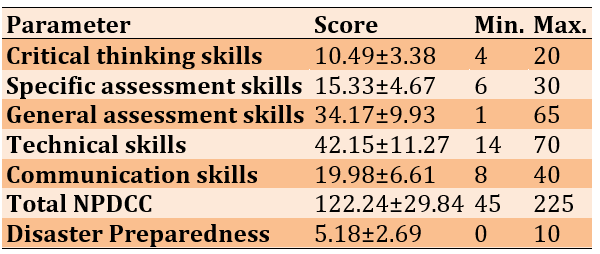

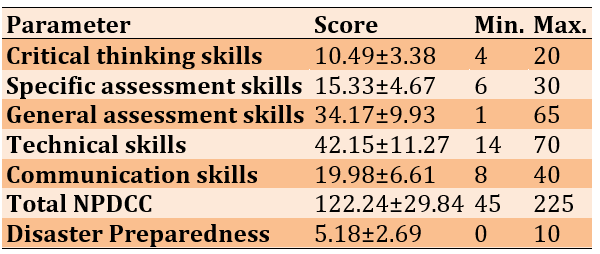

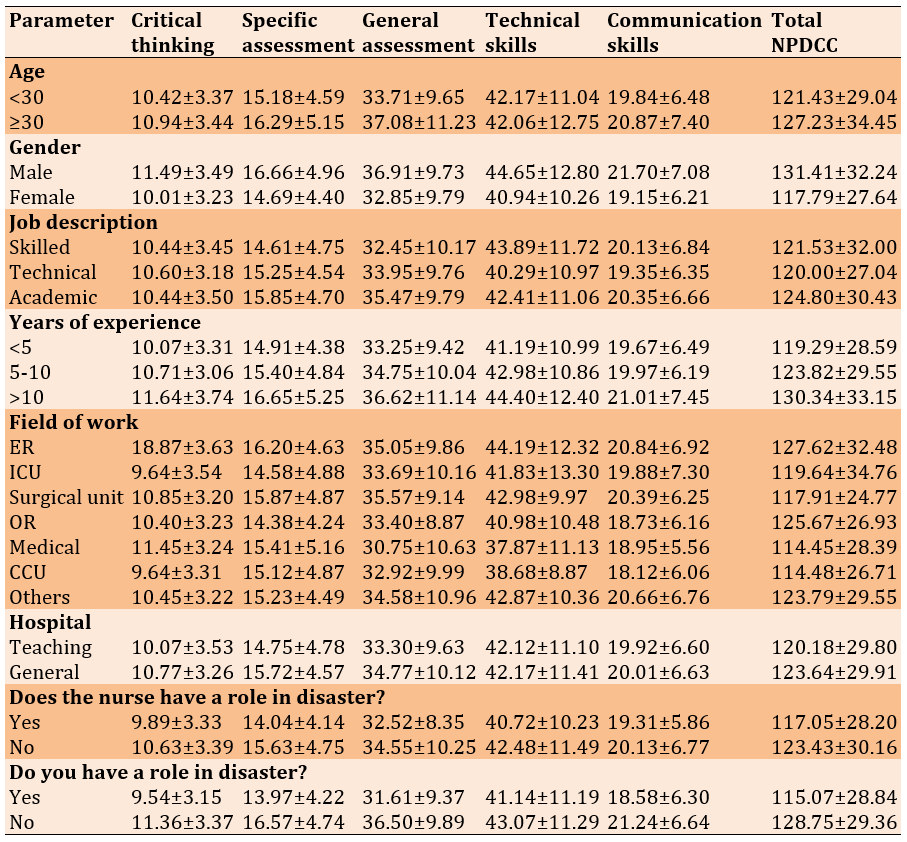

The total NPDCC score was 122.24±29.84, and the nurse's perception of disaster preparedness was 5.18±2.69 (Table 2). The scores of the studied parameters were reported in Table 3.

Table 2. The mean of subdomains and a total of disaster preparedness and NPDCC scale

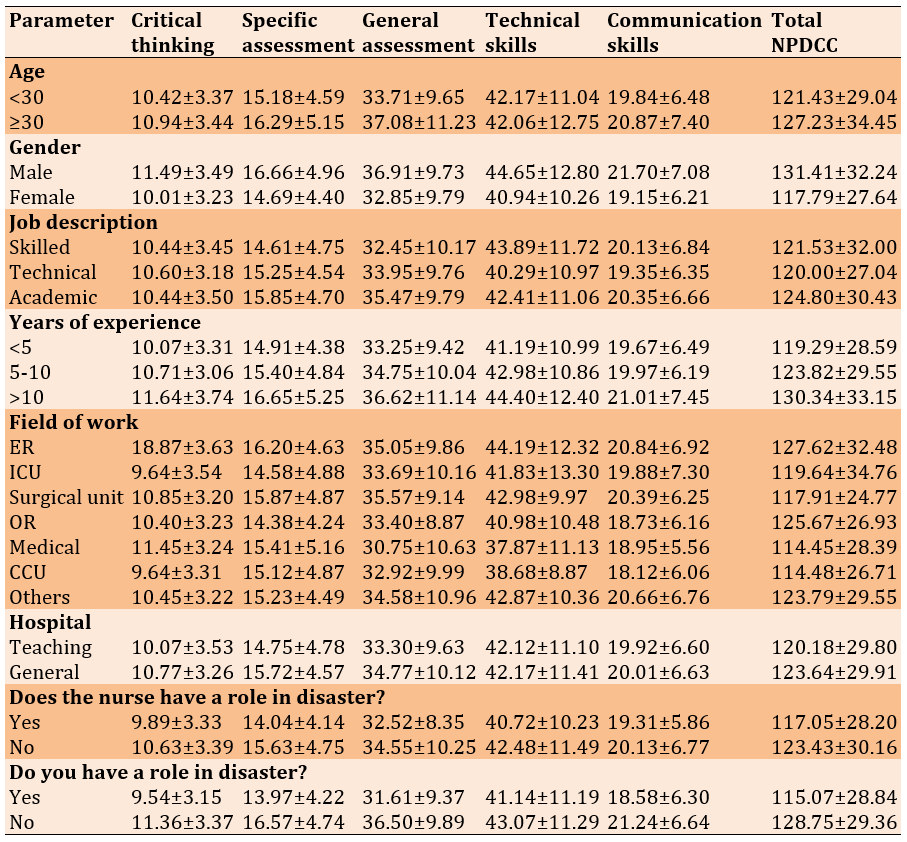

Table 3. The mean of subdomains and total NPDCC scale according to the socio-demographic characteristics

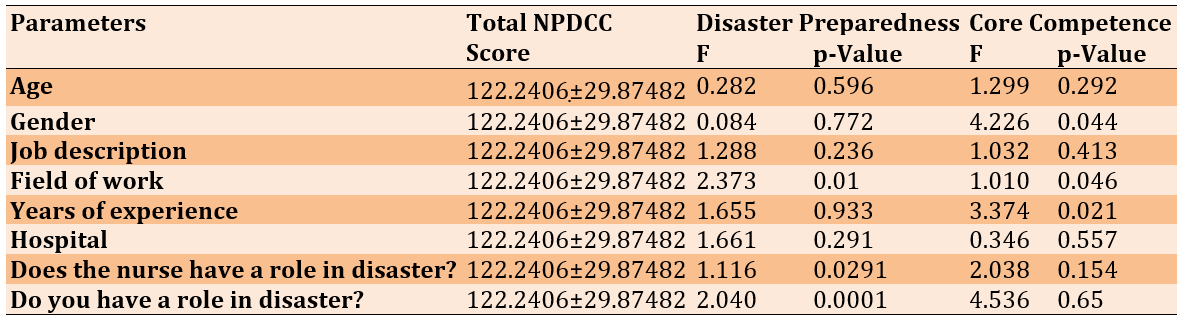

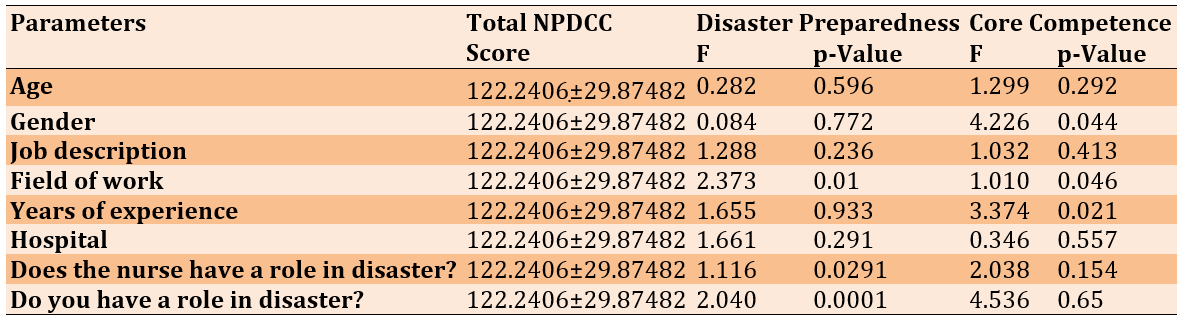

The total NPDCC score according to gender (p=0.044) and years of experience (p=0.021) had significant associations with the core competence perception. Also, the total NPDCC score according to the field of work (p=0.01), the nurses have a role in disasters (p=0.0291), and you have a role in disasters (p=0.0001) had significant associations with the disaster preparedness perception (Table 4).

Table 4. The association of the total NPDCC score with disaster preparedness perception and core competence perception according to the socio-demographic characteristics of nurses (n=374)

Discussion

This study assesses nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness and core competence in the Iraqi context. A total of 374 nurses from multi-centers participated voluntarily. The findings revealed that total core competence is 122.44±29.87, where they feel not competent, and 5.18 out of 10 felt moderately prepared. This result is different from Taskiran & Baykal [3], while in the same study, the NPDCC scale is higher, indicating that Turkish nurses also felt unprepared. However, these results are lower than the study conducted in Iran by Chingiani et al. [32], where the mean preparedness scale was 6.75 out of 10, and the total NPDCC scale was 2.88 out of 5.

Interestingly, our study found that the NPDCC score increases with male nurses (p=0.044). In contrast, female nurses had a lower mean score. This contrasts with Chingiani et al. [32], who reported no significant gender differences in nurses' core competence perception. These findings suggest that gender-related differences in disaster preparedness may be influenced by cultural, educational, or institutional factors unique to each country.

Moreover, our findings highlight that core competence scores increase with professional nursing experience, particularly for those with over 10 years in the field. In contrast, nurses with less than five years of experience had the lowest core competence mean score. Both groups reported no perception of disaster preparedness, aligning with Lai et al. [33], who found junior nurses unprepared for disaster response and feel incompetent. These findings indicate that while experience enhances certain competencies, formal disaster training is essential for improving preparedness, particularly among younger nurses.

Regardless of the job description and hospital type, emergency nurses in our study felt more prepared and competent in disaster response compared to nurses in other units. They exhibited higher critical thinking skills and superior communication skills. Their total NPDCC score was significantly higher than that of nurses working in other units, particularly medical unit nurses, who had the lowest mean score and the lowest mean in general assessment skills. These results align with prior research by Taskiran & Baykal [3] and Nilsson et al. [34], which found that emergency nurses possess the second-highest critical thinking skills after nurse managers. This suggests that exposure to high-pressure, fast-paced environments in emergency settings may contribute to greater preparedness and problem-solving capabilities in disaster situations.

However, an analysis of variance in our study found no significant association between demographic characteristics such as job description and hospital type with nurses’ core competence, which contradicts findings by Uhm et al. [35]. Their study demonstrated that institutional and personal disaster preparedness levels among emergency medical technicians were significantly associated with job roles and training opportunities. This discrepancy underscores the need for further research to explore how institutional structures and educational frameworks influence nurses' disaster preparedness.

Additionally, the perception of disaster preparedness among nurses in our study was notably low (2.33 out of 5), indicating a general lack of confidence in their ability to respond effectively to disasters. This contradicts earlier research suggesting that nurses, particularly those with specialized disaster training, tend to report higher confidence levels in their preparedness. Our findings indicate that a significant portion of the nursing workforce (81.3%) does not perceive themselves as having a role in disaster response. In comparison, 52.3% explicitly stated that they believe they have no responsibilities in disaster management. This lack of perceived responsibility may contribute to overall unpreparedness and highlights the need for targeted educational interventions to clarify nurses' roles in disaster situations.

Further, our study found that nurses working in medical, coronary care unit (CCU), operating room, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings had the lowest mean NPDCC scores. Previous research has consistently shown that nurses in specialized units tend to have lower disaster preparedness levels due to their limited exposure to emergency response scenarios [36-39]. This is concerning, as these units play a critical role in patient management during large-scale disasters, underscoring the necessity for disaster-specific training programs in these departments.

This study contributes to the existing literature by assessing nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness and core competence in Iraq. This area has been largely overlooked in previous research. However, the study faced challenges in accessing nurses working in critical care units, and there was limited time and collaboration available to include nurses from primary healthcare centers, which affected the overall sample size. Despite these limitations, our findings emphasize the urgent need for continuous professional development, structured disaster training programs, and the establishment of a dedicated database for tracking nurses' disaster preparedness levels in Iraq.

Given the increasing frequency and severity of disasters globally, investing in competency-based disaster education is imperative. Previous studies have demonstrated that simulation-based training improves nurses' preparedness and confidence in disaster response [40, 41]. By integrating such approaches into nursing curricula and hospital training programs, healthcare systems can better equip nurses with the necessary skills and knowledge to manage disasters effectively. Furthermore, policy-level changes, such as incorporating mandatory disaster preparedness training in nursing accreditation programs, could be crucial in bridging the current competency gaps observed in this study.

In conclusion, our findings reveal substantial gaps in Iraqi nurses’ disaster preparedness and core competence, with significant variations based on gender, experience, and unit placement. The lack of clear role perception among nurses, particularly those outside emergency settings, poses a major challenge to disaster response efforts. A comprehensive strategy encompassing education, hands-on training, and policy interventions is essential to enhance disaster readiness. Strengthening disaster preparedness among nurses will improve response efforts and contribute to a more resilient healthcare system in the face of future emergencies.

Conclusion

Most nurses have no clear image of their role in disaster preparedness and are incompetent. However, disaster core competencies and skills are required to face upcoming disasters.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Nachivin for permitting them to use the NPDCC scale. They also acknowledge the hospitals in Baghdad and Samawa for their support and for providing the IRB approvals.

Ethical Permissions: The authors obtained permission from the scientific committee in the College of Nursing at the University of Al-Muthanna (Code: 155- 22/2/2024) in Samawa and Baghdad.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflict of interests is mentioned.

Authors' Contribution: Jaafar SA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Al-Jubouri MB (Second Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mousa AM (Third Author), Introduction Writer /Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Bachai GE (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: No funding is reported.

Disasters are natural, artificial, and technological, need rapid response, are challenging to prepare, and increase the negative impact in the future related to climate changes, displacement, conflicts, and public health emergencies [1]. There is a lack of nurses' preparedness and core competence, and there is a gap in legislation, education programs, and awareness of the pre-disaster. The nurse's role is under development, and there is no clear coverage for education programs and training in many regions [2-4]. Long-standing effects following disasters are remarkable problems [5]. People may suffer from socioeconomic [6], behavioral, biological [7], and psychological problems, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, injuries, and disabilities, and nurses need to be competent in dealing with such cases [8].

Disaster preparedness among nurses is crucial in response, recovery, and evaluation [9]. The role of the nurses in disaster goes beyond routine daily work [10]. In some countries with a shortage of medical doctors, nurses lead disaster programs through response and rehabilitation [11]. Despite competency-based education expanding worldwide, some areas still depend on evaluation trainees for the nurses' activities and performances. Competency is well defined in the literature as the ability of nurses to apply tasks and activities with perfect performance, and these activities must be measurable and observable [12-14]. Competencies of disasters include the use of professional skills such as critical thinking, specific skills, general skills, technical skills, and communication and coordination of operations [3, 12]. Due to their vital role, nurses' preparedness is increasingly significant in disaster-prone areas and specific geographical regions [15, 16].

The specific disaster competencies expected of nurses should encompass the four main phases of disaster management: preparedness, response, and recovery. During the preparedness phase, planning, continuous education and training, assessment, and evaluation of activities related to disaster management are carried out [17]. After preparedness, the mitigation phase begins, during which a comprehensive plan is developed to identify risks, formulate strategies to address them and implement interventions to strengthen resilience against disasters. In the response phase, nurses are activated alongside other personnel, focusing on saving lives, reducing infrastructure damage, and supporting survivors by providing basic needs. Finally, the recovery phase is centered on restoring normal levels of social functioning [18].

In addition to these phases, effective disaster management requires a multidisciplinary approach where nurses collaborate with emergency responders, government agencies, and community organizations to ensure a coordinated and efficient response. Nurses play a crucial role in direct patient care and disaster risk communication, public education, and advocacy for improved disaster preparedness policies [19]. Their ability to assess community needs, provide psychological support, and assist in rebuilding healthcare services makes them indispensable in disaster recovery efforts. As disasters become more frequent and complex due to climate change and global health threats, investing in nursing education, simulation-based training, and policy development is essential to enhancing resilience and ensuring a more effective disaster response system [13, 19].

The cornerstone in disaster management is that nurses should be well-trained and prepared to face the effects of the disaster. The training includes new learning and training strategies that can enhance nurses' psychological preparedness during the crisis and their abilities to care for themselves and others [20, 21].

Despite increasing awareness of the importance of possessing the necessary competencies to provide care and respond to disasters and public health emergencies, the definitions of these competencies remain ambiguous; they have not been formally validated, and nurses remain uncertain about their roles in such situations. This uncertainty can lead to hesitation and inefficiency in disaster response, ultimately affecting the quality of care provided to affected individuals [22].

Despite receiving education and training in disaster management, including general knowledge of disasters, the proper use of protective equipment, trauma care, biological information, bioterrorism management, the control and management of infectious diseases in disaster-affected areas, the implementation of disaster policies and plans, the role of hospitals during disasters, and their own roles in emergencies, nurses still lack sufficient knowledge [17-21]. This knowledge gap is particularly concerning as it directly impacts their ability to respond effectively in high-pressure situations. Furthermore, many nurses do not receive adequate hands-on experience or simulation-based training, crucial for developing confidence and competence in real-world disaster scenarios [17].

This lack of knowledge is further compounded by a deficiency in practical skills, despite nurses recognizing that a diverse skill set is essential for effectively responding to life-threatening situations [21, 22]. Skills such as rapid triage, emergency wound care, crisis communication, and psychological first aid are often insufficiently covered in training programs, leaving nurses feeling underprepared. Moreover, disaster settings frequently require adaptability, leadership, and decision-making skills under extreme conditions—capabilities many nurses feel inadequately trained for [17].

As a result, the lack of knowledge and skills negatively impacts nurses' confidence in their ability to provide disaster-related patient care and fulfill their expected roles and responsibilities. Many nurses experience anxiety and self-doubt when placed in emergency situations, fearing that they may not be able to act effectively [23]. Additionally, individuals are implicitly expected to suddenly become "strong nurses" when faced with disaster situations, despite insufficient preparation. This unrealistic expectation places significant psychological pressure on nurses, potentially leading to burnout, emotional distress, and reduced job satisfaction over time [17].

To address these challenges, it is essential to develop standardized and validated competency frameworks, ensuring that nurses receive structured education and hands-on training in disaster preparedness and response [17, 22]. Strengthening nursing curricula, increasing access to practical disaster simulations, and integrating psychological resilience training can help nurses feel more confident and capable in crisis situations. Investing in the continuous professional development of nurses and equipping them with the necessary skills and knowledge will enhance disaster response efforts and improve overall public health resilience in emergencies [23].

In Iraq, where the largest mass gatherings occur [24], disaster preparedness and nurse training are necessary to face future challenges [25]. Although experience with previous people displacement related to terrorist impact, wars for decades, and geographical location near the countries are active with earthquakes [26, 27], Iraq still follows traditional responses with no emergency preparedness in the last years [28, 29]. Nevertheless, there is no survey evidence of the level of readiness and core competence perception among nurses, only knowledge and practice assessment [29]. Therefore, the need to evaluate nurses' preparedness and core competence is a part of facing potential future risks and describing the level of disaster preparedness.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February 22 to August 15, 2024, in four teaching hospitals (Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Al-Yarmouk Teaching Hospital, Al-Kindi Teaching Hospital, and Al-Hussein Teaching Hospital) and three general hospitals (Al-Rumaitha Hospital, Alkhudier Hospital, and Al-Warkaa Hospital) in the mid-and south of Iraq. The sample size calculation was done using a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. Based on this method, the survey targeted 380 nurses. Only 374 nurses completed the survey. The nurses who were invited have completed at least one year of experience. Furthermore, nurses who work in different fields, such as the ER, ICU, CCU, and med-surg. units, OR, infection control, continuous education, and hemodialysis. A convenience method was used to select the study sample.

Instrument

The demographic characteristics (age, gender, job description, area of expertise, years of experience, and hospital type) were recorded in the first part. The second part had nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness, including using a visual scale to ask questions about how they feel prepared for disasters. The answers include (0) having no preparedness and (10) being fully prepared for disasters. The confirmed Turkish scale of "nurses' perception of disaster core competence (NPDCC)”, developed by Celik & Nahcivan [30, 31] (Cronbach's alpha=0.96), also used by Taskiran & Baykal [3], the scale has 45 items in five domain includes, critical thinking (items 1-4), specific assessment skills (items 5-10), general assessment skills (items 11-23), technical skills (items 24-37), and communication skills (items 38-45). The scale scored based on a 5-Likert scale (“this needs to be taught to” I can do and teach it 5). The minimum to maximum score range is between 45 and 225. Lower scores mean lower perception and core competence; A high score means better perception and core competence. The corresponding authors get permission to use the tool from the original authors via e-mail. The survey was conducted on 380 nurses.

Procedure

The authors obtained permission from the scientific committee in the College of Nursing at the University of Al-Muthanna. The consent forms were distributed to the participants, who had the right to withdraw without penalty. The current study's data collection involved a face-to-face method. The three authors were recruited to collect the data; Two were collected from Baghdad City hospitals, and another author collected the data from the Al-Muthanna governorate hospitals. An anonymous survey was used to collect the data from the participants. Each participant took 5-15 minutes to complete the survey. The questionnaires were distributed at rest to avoid working interruptions in the emergency, operation room, and intensive care unit.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS 20 and Microsoft Excel 2010 by an independent two-sample t-test analysis of variance (ANOVA) at p<0.05 significant level.

Findings

The mean age of 374 nurses was 28.2±5.4 years. More than half of nurses were female (67.4%). Their job description was an academic nurse; most worked in the emergency unit (22.7%). The mean of years of experience is 5.75 years, and the standard deviation is 5.30 years. More than half of the study participants (59.4%) were affiliated with the general (public) hospital. Most participants (81.3%) believed that the nurses have no role in the disaster, and half felt they have no role in the disaster (52.3%; Table 1).

Table1. The frequency of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (n=374)

The total NPDCC score was 122.24±29.84, and the nurse's perception of disaster preparedness was 5.18±2.69 (Table 2). The scores of the studied parameters were reported in Table 3.

Table 2. The mean of subdomains and a total of disaster preparedness and NPDCC scale

Table 3. The mean of subdomains and total NPDCC scale according to the socio-demographic characteristics

The total NPDCC score according to gender (p=0.044) and years of experience (p=0.021) had significant associations with the core competence perception. Also, the total NPDCC score according to the field of work (p=0.01), the nurses have a role in disasters (p=0.0291), and you have a role in disasters (p=0.0001) had significant associations with the disaster preparedness perception (Table 4).

Table 4. The association of the total NPDCC score with disaster preparedness perception and core competence perception according to the socio-demographic characteristics of nurses (n=374)

Discussion

This study assesses nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness and core competence in the Iraqi context. A total of 374 nurses from multi-centers participated voluntarily. The findings revealed that total core competence is 122.44±29.87, where they feel not competent, and 5.18 out of 10 felt moderately prepared. This result is different from Taskiran & Baykal [3], while in the same study, the NPDCC scale is higher, indicating that Turkish nurses also felt unprepared. However, these results are lower than the study conducted in Iran by Chingiani et al. [32], where the mean preparedness scale was 6.75 out of 10, and the total NPDCC scale was 2.88 out of 5.

Interestingly, our study found that the NPDCC score increases with male nurses (p=0.044). In contrast, female nurses had a lower mean score. This contrasts with Chingiani et al. [32], who reported no significant gender differences in nurses' core competence perception. These findings suggest that gender-related differences in disaster preparedness may be influenced by cultural, educational, or institutional factors unique to each country.

Moreover, our findings highlight that core competence scores increase with professional nursing experience, particularly for those with over 10 years in the field. In contrast, nurses with less than five years of experience had the lowest core competence mean score. Both groups reported no perception of disaster preparedness, aligning with Lai et al. [33], who found junior nurses unprepared for disaster response and feel incompetent. These findings indicate that while experience enhances certain competencies, formal disaster training is essential for improving preparedness, particularly among younger nurses.

Regardless of the job description and hospital type, emergency nurses in our study felt more prepared and competent in disaster response compared to nurses in other units. They exhibited higher critical thinking skills and superior communication skills. Their total NPDCC score was significantly higher than that of nurses working in other units, particularly medical unit nurses, who had the lowest mean score and the lowest mean in general assessment skills. These results align with prior research by Taskiran & Baykal [3] and Nilsson et al. [34], which found that emergency nurses possess the second-highest critical thinking skills after nurse managers. This suggests that exposure to high-pressure, fast-paced environments in emergency settings may contribute to greater preparedness and problem-solving capabilities in disaster situations.

However, an analysis of variance in our study found no significant association between demographic characteristics such as job description and hospital type with nurses’ core competence, which contradicts findings by Uhm et al. [35]. Their study demonstrated that institutional and personal disaster preparedness levels among emergency medical technicians were significantly associated with job roles and training opportunities. This discrepancy underscores the need for further research to explore how institutional structures and educational frameworks influence nurses' disaster preparedness.

Additionally, the perception of disaster preparedness among nurses in our study was notably low (2.33 out of 5), indicating a general lack of confidence in their ability to respond effectively to disasters. This contradicts earlier research suggesting that nurses, particularly those with specialized disaster training, tend to report higher confidence levels in their preparedness. Our findings indicate that a significant portion of the nursing workforce (81.3%) does not perceive themselves as having a role in disaster response. In comparison, 52.3% explicitly stated that they believe they have no responsibilities in disaster management. This lack of perceived responsibility may contribute to overall unpreparedness and highlights the need for targeted educational interventions to clarify nurses' roles in disaster situations.

Further, our study found that nurses working in medical, coronary care unit (CCU), operating room, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings had the lowest mean NPDCC scores. Previous research has consistently shown that nurses in specialized units tend to have lower disaster preparedness levels due to their limited exposure to emergency response scenarios [36-39]. This is concerning, as these units play a critical role in patient management during large-scale disasters, underscoring the necessity for disaster-specific training programs in these departments.

This study contributes to the existing literature by assessing nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness and core competence in Iraq. This area has been largely overlooked in previous research. However, the study faced challenges in accessing nurses working in critical care units, and there was limited time and collaboration available to include nurses from primary healthcare centers, which affected the overall sample size. Despite these limitations, our findings emphasize the urgent need for continuous professional development, structured disaster training programs, and the establishment of a dedicated database for tracking nurses' disaster preparedness levels in Iraq.

Given the increasing frequency and severity of disasters globally, investing in competency-based disaster education is imperative. Previous studies have demonstrated that simulation-based training improves nurses' preparedness and confidence in disaster response [40, 41]. By integrating such approaches into nursing curricula and hospital training programs, healthcare systems can better equip nurses with the necessary skills and knowledge to manage disasters effectively. Furthermore, policy-level changes, such as incorporating mandatory disaster preparedness training in nursing accreditation programs, could be crucial in bridging the current competency gaps observed in this study.

In conclusion, our findings reveal substantial gaps in Iraqi nurses’ disaster preparedness and core competence, with significant variations based on gender, experience, and unit placement. The lack of clear role perception among nurses, particularly those outside emergency settings, poses a major challenge to disaster response efforts. A comprehensive strategy encompassing education, hands-on training, and policy interventions is essential to enhance disaster readiness. Strengthening disaster preparedness among nurses will improve response efforts and contribute to a more resilient healthcare system in the face of future emergencies.

Conclusion

Most nurses have no clear image of their role in disaster preparedness and are incompetent. However, disaster core competencies and skills are required to face upcoming disasters.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Nachivin for permitting them to use the NPDCC scale. They also acknowledge the hospitals in Baghdad and Samawa for their support and for providing the IRB approvals.

Ethical Permissions: The authors obtained permission from the scientific committee in the College of Nursing at the University of Al-Muthanna (Code: 155- 22/2/2024) in Samawa and Baghdad.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflict of interests is mentioned.

Authors' Contribution: Jaafar SA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Al-Jubouri MB (Second Author), Methodologist/ Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Mousa AM (Third Author), Introduction Writer /Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Bachai GE (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%)

Funding/Support: No funding is reported.

Keywords:

References

1. IFRC. What is a disaster? [Internet]. Geneva: IFRC [cited 2023 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.ifrc.org/our-work/disasters-climate-and-crises/what-disaster. [Link]

2. Hasan MK, Younos TB, Farid ZI. Nurses' knowledge, skills and preparedness for disaster management of a Megapolis: Implications for nursing disaster education. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;107:105122. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105122]

3. Taskiran G, Baykal U. Nurses' disaster preparedness and core competencies in Turkey: A descriptive correlational design. Int Nurs Rev. 2019;66(2):165-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/inr.12501]

4. Labrague LJ, Yboa BC, McEnroe-Petitte DM, Lobrino LR, Brennan MGB. Disaster preparedness in Philippine nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(1):98-105. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12186]

5. Nomura S, Parsons AJ, Hirabayashi M, Kinoshita R, Liao Y, Hodgson S. Social determinants of mid-to long-term disaster impacts on health: A systematic review. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016;16:53-67. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.01.013]

6. Mao W, Agyapong VI. The role of social determinants in mental health and resilience after disasters: Implications for public health policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2021;9:658528. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2021.658528]

7. Gautam S, Menachem J, Srivastav SK, Delafontaine P, Irimpen A. Effect of Hurricane Katrina on the incidence of acute coronary syndrome at a primary angioplasty center in New Orleans. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(3):144-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181b9db91]

8. WHO. Mental health in emergencies [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2022, Mar,16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-in-emergencies. [Link]

9. Martono M, Satino S, Nursalam N, Efendi F, Bushy A. Indonesian nurses' perception of disaster management preparedness. Chin J Traumatol. 2019;22(1):41-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cjtee.2018.09.002]

10. Havealeta M, Kaho F, Tuipulotu AAA. Tonga: Cyclone Ian, Ha'apai islands. In: The role of nurses in disaster management in Asia Pacific. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 105-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-41309-9_11]

11. Bonito S, Minami H. The role of nurses in disaster management in Asia Pacific. Cham: Springer; 2019. [Link]

12. Loke AY, Li S, Guo C. Mapping a postgraduate curriculum in disaster nursing with the International Council of Nursing's Core Competencies in Disaster Nursing V2. 0: The extent of the program in addressing the core competencies. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;106:105063. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105063]

13. Latif M, Abbasi M, Momenian S. The effect of educating confronting accidents and disasters on the improvement of nurses' professional competence in response to the crisis. Health Emerg Disasters Q. 2019;4(3):147-56. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/hdq.4.3.147]

14. Satoh M, Iwamitsu H, Yamada E, Kuribayashi Y, Yamagami-Matsuyama T, Yamada Y. Disaster nursing knowledge and competencies among nursing university students participated in relief activities following the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes. SAGE Open Nurs. 2018;4:2377960818804918. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2377960818804918]

15. Labrague LJ, Hammad K. Disaster preparedness among nurses in disaster-prone countries: A systematic review. Australas Emerg Care. 2024;27(2):88-96. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.auec.2023.09.002]

16. Wang Y, Liu Y, Yu M, Wang H, Peng C, Zhang P, et al. Disaster preparedness among nurses in China: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Res. 2023;31(1):e255. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000537]

17. Alfuqaha AN, Alosta MR, Khalifeh AH, Oweidat IA. Jordanian nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness and core competencies. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2024;8:e96. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2024.81]

18. Alkhalaileh M. Attitude of Jordanian nursing educators toward integration of disaster management in nursing curricula. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;15(4):478-483. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2020.42]

19. Yu M, Yang C, Li Y. Big data in natural disaster management: a review. Geosci. 2018;8(5):165. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/geosciences8050165]

20. Said NB, Chiang VC. The knowledge, skill competencies, and psychological preparedness of nurses for disasters: A systematic review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2020;48:100806. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2019.100806]

21. Horrocks P, Hobbs L, Tippett V, Aitken P. Paramedic disaster health management competencies: a scoping review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34(3):322-329. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X19004357]

22. Hutton A, Veenema TG, Gebbie K. Review of the International Council of Nurses (ICN) framework of disaster nursing competencies. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(6):680-683. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X1600100X]

23. Li SM, Li XR, Yang D, et al. Research progress in disaster nursing competency framework of nurses in China. Chinese Nurs Res. 2016;3(4):154-157. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cnre.2016.11.003]

24. Lami S, Ayed A. Predictors of nurses' practice of eye care for patients in intensive care units. SAGE Open Nursing. 2023;9:23779608231158491. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/23779608231158491]

25. Abdul Hussein AF, Khalaf Awad A. Assessment of knowledge preparedness nurses for disaster management in primary health-care centers in Al-Hilla, Iraq. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;10(2):227-231. [Link]

26. Ediz Ç, Yanik D. Disaster preparedness perception, pyschological resiliences and empathy levels of nurses after 2023 Great Turkiye earthquake: Are nurses prepared for disasters: A risk management study. Public Health Nurs. 2024;41(1):164-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/phn.13267]

27. Nasrabadi AN, Naji H, Mirzabeigi G, Dadbakhs M. Earthquake relief: Iranian nurses' responses in Bam, 2003, and lessons learned. Int Nurs Rev. 2007;54(1):13-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00495.x]

28. Al-Shamsi MTM. Disaster risk reduction in Iraq. JÀMBÁ J Disaster Risk Stud. 2019;11(1):a656. [Link] [DOI:10.4102/jamba.v11i1.656]

29. Aykan EB, Fidancı BE, Yıldız D. Assessment of nurses' preparedness for disasters. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;68:102721. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102721]

30. Winarti W, Gracya N. Exploring nurses' perceptions of disaster preparedness competencies. Nurse Media J Nurs. 2023;13(2):236-245. [Link] [DOI:10.14710/nmjn.v13i2.51936]

31. Celik AO, Diplas P, Dancey CL, Valyrakis M. Impulse and particle dislodgement under turbulent flow conditions. Phys Fluids. 2010;22(4). [Link] [DOI:10.1063/1.3385433]

32. Chegini Z, Arab-Zozani M, Kakemam E, et al. Disaster preparedness and core competencies among emergency nurses: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2022;9(2):1294-1302. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nop2.1172]

33. Lai J, Wen G, Gu C, Ma C, Chen H, Xiang J, et al. The core competencies in disaster nursing of new graduate nurses in Guangdong, China: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2024;77:103987. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2024.103987]

34. Nilsson J, Johansson E, Carlsson M, Florin J, Leksell J, Lepp M, et al. Disaster nursing: Self-reported competence of nursing students and registered nurses, with focus on their readiness to manage violence, serious events and disasters. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;17:102-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nepr.2015.09.012]

35. Uhm JY, Choi MY. Mothers' needs regarding partnerships with nurses during care of infants with congenital heart defects in a paediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;54:79-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2019.07.003]

36. Hasan MK, Fahmi A, Jisa TJ, Rokib RH, Borna JY, Fardusi J, et al. Predictors of Bangladeshi registered nurses' disaster management knowledge, skills, and preparedness. Prog Disaster Sci. 2024;22:100324. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pdisas.2024.100324]

37. Baack S, Alfred D. Nurses' preparedness and perceived competence in managing disasters. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2013;45(3):281-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12029]

38. Ibrahim FAA. Nurses' knowledge, attitudes, practices and familiarity regarding disaster and emergency preparedness-Saudi Arabia. Am J Nurs Sci. 2014;3(2):18-25. [Link] [DOI:10.11648/j.ajns.20140302.12]

39. regarding disaster and emergency preparedness-Saudi Arabia. [Link]

40. Al Khalaileh MA, Bond E, Alasad JA. Jordanian nurses' perceptions of their preparedness for disaster management. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(1):14-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2011.01.001]

41. Garschagen M, Hagenlocher M, Comes M, Dubbert M, Sabelfeld R, Lee YJ, et al. World risk report 2016. Bonn: United Nations University-EHS; 2016. [Link]

42. INFORM. INFORM global risk index result 2023 [Internet]. Luxembourg: INFORM; 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 18]. Available from: https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/inform-index. [Link]