Volume 17, Issue 3 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(3): 279-291 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2025/06/6 | Accepted: 2025/07/28 | Published: 2025/08/10

Received: 2025/06/6 | Accepted: 2025/07/28 | Published: 2025/08/10

How to cite this article

Wennas O, Haji Ghasem Kashani M, Abiri E, Altememy D. Apoptotic Effect of some Schiff's Base Compounds on HepG2 and Adipose Tissue Stem cells. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (3) :279-291

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1680-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1680-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Zahraa University for Women, Karbala, Iraq

2- Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology and Institute of Biological Sciences, Damghan University, Damghan, Iran

3- Department of Pharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Zahraa University for Women, Karbala, Iraq

2- Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology and Institute of Biological Sciences, Damghan University, Damghan, Iran

3- Department of Pharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Zahraa University for Women, Karbala, Iraq

Full-Text (HTML) (4 Views)

Introduction

Cancer refers to a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation, invasion of cells into adjacent tissues, and metastasis in more advanced stages. Disturbances in cell behavior arise from changes in gene sequences or epigenetic modifications [1-3]. Initially, the cell mass resulting from the uncontrolled proliferation of cells with a high growth rate, without invasion or metastasis, is referred to as a tumor. When the cell mass loses proper organization, the rate of cell proliferation increases, and the cells acquire the ability to invade and metastasize. At this stage, it is termed cancer [4, 5].

Most of the factors that contribute to cancer are associated with DNA sequence changes or mutations. Therefore, like all genetic diseases, cancers are caused by alterations in DNA. Genes involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, when deregulated, can lead to a cancer phenotype. The genetic changes that characterize cancer are sometimes the result of inherited defects [5-8].

Cancer cells in tumor tissue can self-renew and differentiate into specialized cells, and they also exhibit resistance to chemotherapy. The exact origin of these cells is not fully understood; this does not imply that cancer stem cells derive from stem cells. Instead, due to the accumulation of mutations in these cells, they exhibit a phenotype similar to that of stem cells. Cancer stem cells can give rise to different types of cancer cells within a tumor sample, distinguishing them from other cancer cells, which is why they are referred to as tumorigenic [8, 9]. Cancer is not necessarily caused by cancer stem cells, although the terms “cells that lead to cancer” and “cancer stem cells” are sometimes used interchangeably [10].

Currently, the use of stem cells in the treatment of various types of cancers and diseases is under consideration. One notable application of stem cells is in the treatment of liver cancer. Liver cancer begins in one part of the liver and can spread to other areas. Histologically, 80% of liver cancers are classified as hepatocellular carcinoma [11, 12]. Liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. In 2002, 600,000 people in developing countries were diagnosed with liver cancer [13]. The HepG2 cell line is a type of liver cancer cell line that, morphologically, demonstrates high proliferative capacity and low differentiation ability under laboratory conditions [14, 15].

Mesenchymal stem cells are defined as multipotent stem cells capable of self-renewal and proliferation, with the ability to differentiate into at least three mesodermal lineages in a laboratory environment, including chondrocytes, adipocytes, and osteoblasts. They can also differentiate into other cell types from the endodermal and mesodermal lineages, such as liver hepatocytes and neurons [16, 17]. Although these cells are found in most tissues, including the liver, muscle, lung, umbilical cord, and amniotic fluid, they can be specifically harvested from bone marrow and adipose tissue [18, 19].

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue (adipose tissue-derived stem cells: ADSCs or ASCs) can be extracted from fat tissue through liposuction. These cells can self-renew and differentiate into mesodermal lineages such as cartilage, adipose tissue, and bone [20]. The surface markers of ASCs are similar to those of stem cells derived from bone marrow, including CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD44, CD146, and CD166 [21]. However, they can be distinguished by the expression of the CD34 marker [22]. These cells can express and secrete various factors, including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and anti-inflammatory biomarkers associated with the development and progression of cancer, such as IGF, FGF, HGF, TGF-β, VEGF, IL-8, and IL-10 [23].

ASCs can be used in the treatment of various diseases, including autoimmune diseases, MS, diabetes, upper respiratory system disorders, cardiovascular diseases, brain and spinal cord surgeries, wound healing, and cancer [21, 22, 24]. Currently, ASC is a valuable tool in cell therapy that is being considered for cancer treatment [25]. Numerous studies have investigated the role of ASC in cancer treatment, and whether ASCs support or suppresse the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells remains a topic of debate [26, 27].

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death process governed by distinct biochemical and genetic pathways that play a crucial role in tissue development and homeostasis. It also serves as a defense mechanism that eliminates unwanted or damaged cells [28]. In the early stages of apoptosis, cells become rounded, lose their connections with surrounding cells, and shrink. In the later stages, the DNA condenses and is fragmented by endonucleases [29, 30]. Apoptosis occurs 20 times faster than mitosis, maintaining a balance between the increase and decrease of cell populations. Regulators of apoptosis directly or indirectly control the activity of caspases, which are cysteine proteases that play a key role in executing apoptosis by cleaving substrates at specific aspartate residues [31]. Several environmental factors can activate or inhibit apoptosis. Activators of apoptosis include TNF-α, Fas ligands, TGF-β, BAX, other pro-apoptotic family members (such as Bcl-2), and glucocorticoids [32-34].

Schiff bases are compounds formed through condensation reactions between a carbonyl group and an amine. These compounds possess a basic nature due to a pair of non-bonding electrons on nitrogen and act as ligands with Lewis acids, primarily metal ions. Open-Schiff complexes exhibit various structures depending on the coordinating metal used. For instance, cobalt and nickel ions tend to form square planar and octahedral complexes, while copper ions typically form tetrahedral structures. Many Schiff base complexes are utilized as drugs with a wide range of biological properties against bacteria, fungi, microbes, certain tumors, and cancer [35, 36].

In recent years, the vanadium-Schiff base complex has garnered increasing attention from chemists. Due to its biological role, vanadium complexes are involved in haloperoxidation, nitrogen fixation, phosphorization, mimicking the role of insulin, inhibiting tumor growth, and regulating glycogen metabolism, among other functions [37, 38].

Schiff base complexes of copper and nickel (Cu and Ni complexes) derived from 2,6-diacetylpyridine and 2-pyridine carboxaldehyde exhibit antibacterial activity against various bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [39, 40]. Additionally, anti-cancer compounds containing copper as a central metal have been researched. Copper-Schiff base complexes have shown promise in cancer treatment, with [Cu(pyimpy)Cl2] identified as the most effective combination [41, 42].

Considering the importance of the toxicity and apoptotic properties of anticancer compounds, only agents with minimal apoptotic and toxic effects on cancer cells can be introduced as ideal anticancer drugs. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the apoptotic effect of Schiff base compounds derived from 2-hydroxynaphthaldehyde and 2-chloroethylamine, as well as manganese complexes, on HepG2 cells compared to ASCs. Since these tested materials were prepared at the Faculty of Chemistry of Damghan University in Iran, the researchers felt it necessary to investigate and report the anticancer properties and apoptotic effects of these materials.

Materials and Methods

In this experimental research, three chemicals—Bis(2-{(E)-[(2-Bromoethyl)imino(methyl)]}6-methoxyphenolate) manganese(II) (naph(br)2mn), Bis(2-{(E)-[(2-bromoethyl)imino(methyl)]}6-methoxyphenolate) nickel(II) (naph(br)2Ni), and the Schiff base ligand 2-{(E)-[(2-bromoethyl)imino(methyl)]}6-methoxyphenol (naph-Br))—were synthesized by researchers at the Faculty of Chemistry of Damghan University in Iran under the guidance of respected professors.

Experimental groups included a control group, in which the cells were cultured in culture medium and serum without the presence of chemicals, th control group+solvent, in which, in addition to culture medium and serum, the maximum amount of solvent present in the treatment group was also added, and the treatment group, in which the cells were exposed to the desired chemical substances at the specified concentrations.

This study adheres to internationally accepted standards for animal research, following the 3Rs principle. The ARRIVE guidelines were employed for reporting experiments involving live animals, promoting ethical research practices.

The laboratory studies involved the extraction and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from rat adipose tissue, the culture of HepG2 cancer cells, the investigation of the viability of mesenchymal stem cells and HepG2 cancer cells in the presence of the drug using the proliferation test and cell counting, the examination of the effect of Schiff open complexes on the proliferation rate of mesenchymal stem cells and HepG2 cancer cells using the MTT method, and the assessment of cell proliferation rates through the Ki67 immunocytochemistry method.

Adipose tissue was isolated from a female rat from the area between the two scapulae under sterile conditions. After mechanical digestion and chemical digestion with collagenase enzyme, 2 ml of culture medium (DMEM+10% serum) was added, followed by centrifugation. The tissue was then transferred to a culture flask containing DMEM+10% serum and incubated.

Cancer cells were obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. The cells were cultured in an incubator (temperature 37°C, humidity 95%, and CO2 5%), with the medium changed every 48 hours, using DMEM culture medium containing 10% FBS serum [41, 42]. Passage was performed when the cells reached 80% confluence in the flask. The doubling time of the cancer cell population is approximately 38 hours.

Cell viability and proliferation were evaluated using a Neubauer slide. To count the number of cells, the cells were first thoroughly trypsinized, and then the cell suspension was transferred into a Falcon tube and centrifuged. The supernatant was discarded, and fresh culture medium was added to the cell pellet, which was then pipetted thoroughly. Next, 10µl of this suspension were placed on a Neubauer slide, and a cover slip was gently positioned on top for observation with a light microscope. After counting the cells in the four corners of the Neubauer slide, the following formula was used to calculate the number of cells in a volume of 3ml:

The doubling time of ASC and HepG2 cancer cells was evaluated using the MTT assay. Mesenchymal stem cells and HepG2 cancer cells were cultured individually at a density of 15,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate with 100µl of DMEM culture medium and 10% serum until the density reached 40-50%. The proliferation rate of HepG2 mesenchymal stem cells treated with the desired chemicals at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µmol over 24 hours was then investigated. Subsequently, 10 µl of the WST-1 kit solution was added to the culture medium of the cells. At time intervals of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours after adding the WST-1 kit, the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450nm using the ELISA reader (BioTek).

HepG2 mesenchymal stem cells were cultured, and when the cell density reached 40-50%, the chemicals were added. After 24 hours, anti-Ki-67 immunohistochemistry was performed using the primary antibody (abcam-ab833) and the secondary antibody (Goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP).

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 software. Statistical calculations were performed to investigate differences between groups using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for behavioral data. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Finally, corresponding graphs were created using Excel.

Findings

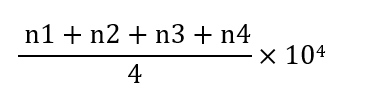

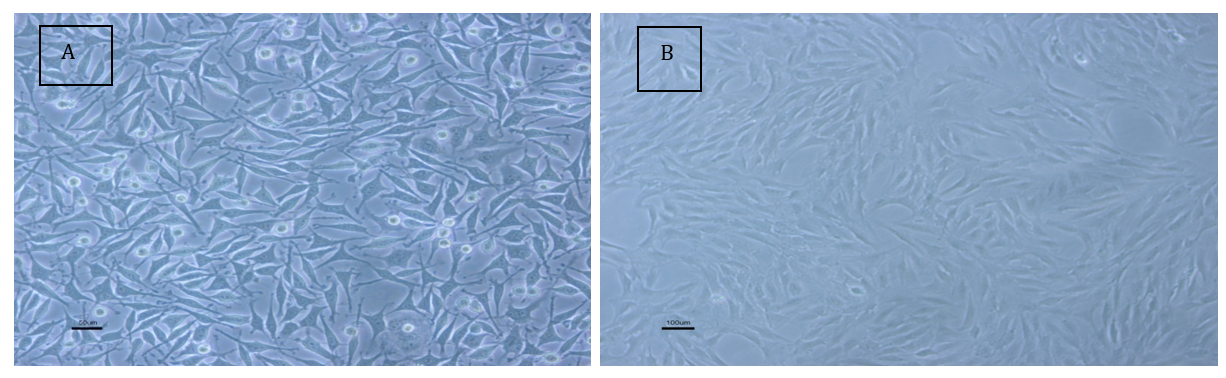

HepG2 cells exhibited a high proliferative capacity in the laboratory setting. They displayed a polygonal and elongated appearance. In contrast, the adipose stem cells appeared pseudo-fibroblastic, with lower proliferative ability and a spindle-shaped, elongated appearance. Additionally, they had a lower density (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Morphological examination of HepG2 cells; A: HepG2 cancer cells; B: Adipose stem cells from rats.

ASC and HepG2 cancer cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 15,000 cells per well in DMEM with 10% serum until the cell density reached 40-50%. The cells were then treated with the desired chemicals at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM for 24 hours. The survival rate, as well as the rate of proliferation of stem and cancer cells, were investigated.

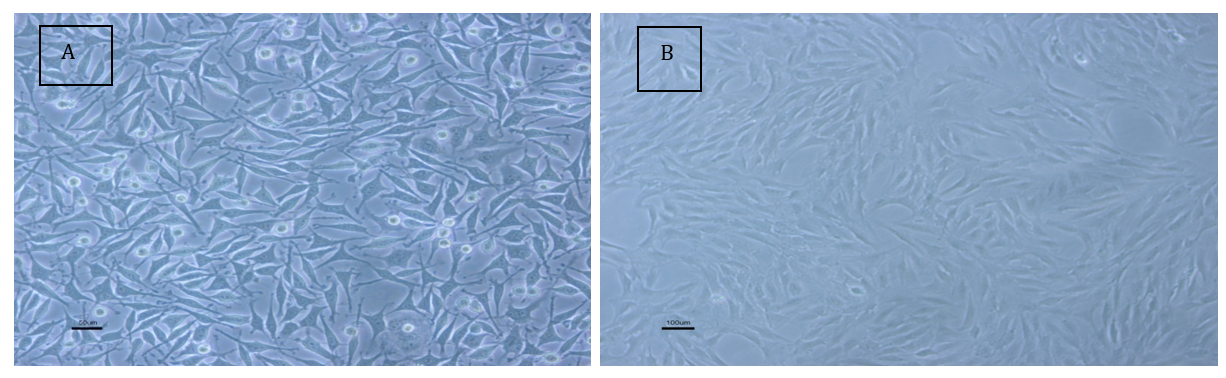

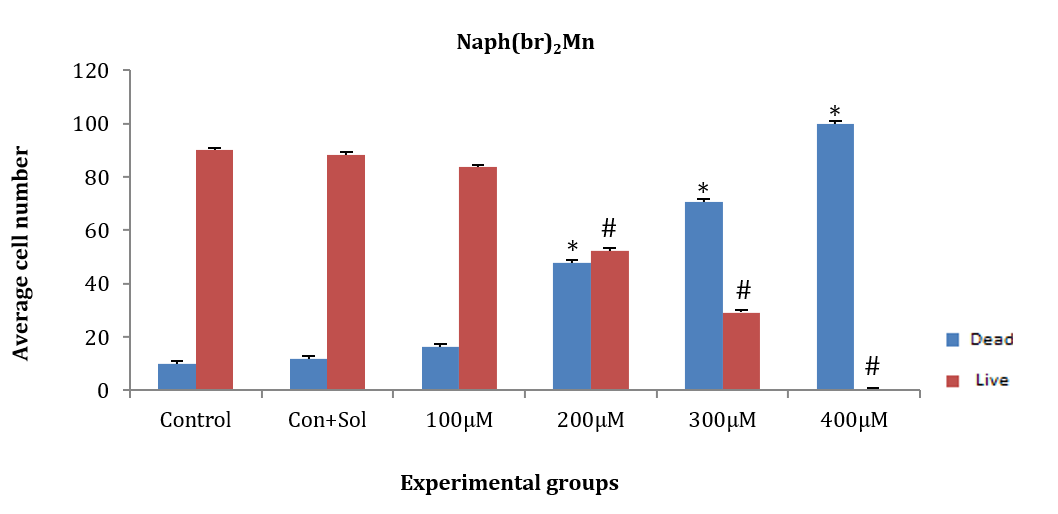

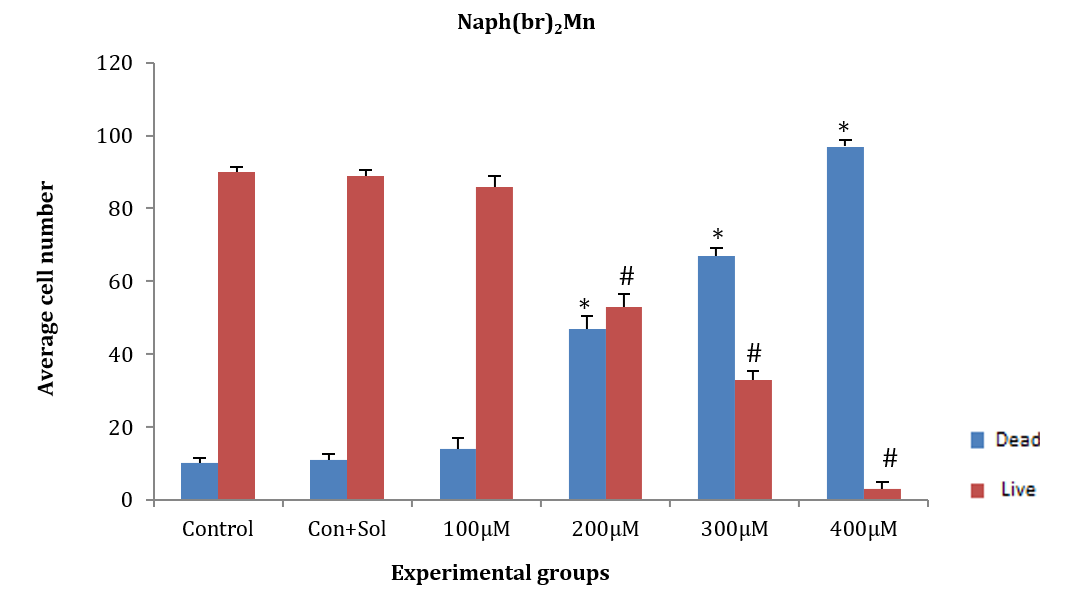

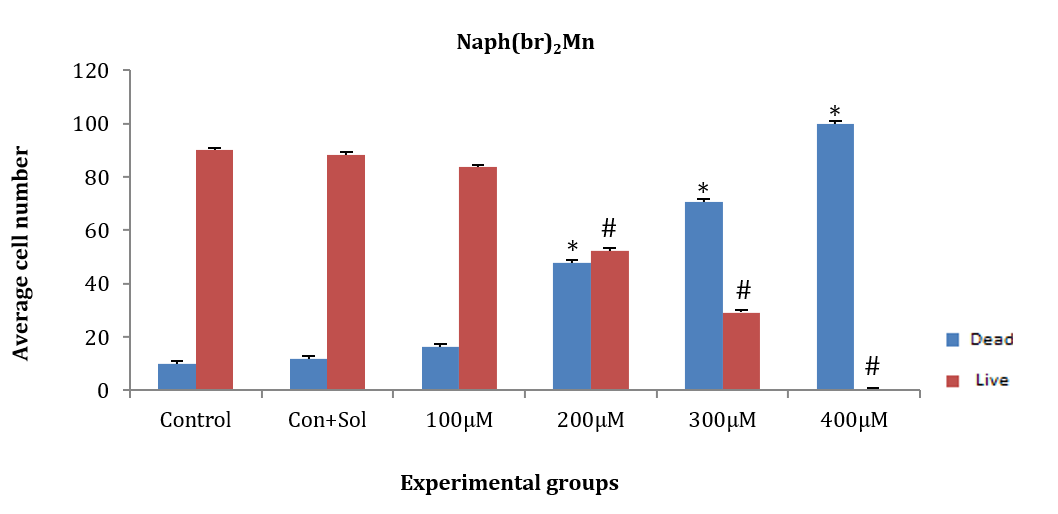

ASCs were treated for 24 hours with the chemical substance naph(br)2Mn at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, and 400µM. There was no significant difference in the average number of dead and alive cells at the concentration of 100µM compared to the control and control+solvent groups. In contrast, the number of dead and alive cells at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400µM showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=285.14, p=0.001). In the 400µM group, more than 98% of the cells died after exposure to the chemical for 24 hours, with only a few surviving. Therefore, this concentration was not deemed suitable for further research. Additionally, at the 200µM concentration, there was no significant difference between the average numbers of dead and live cells; however, at the 300µM concentration, a significant difference was observed between dead and live cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of naph(br)2Mn on adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) after 24 hours.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control+solvent group.

# Significant difference in mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

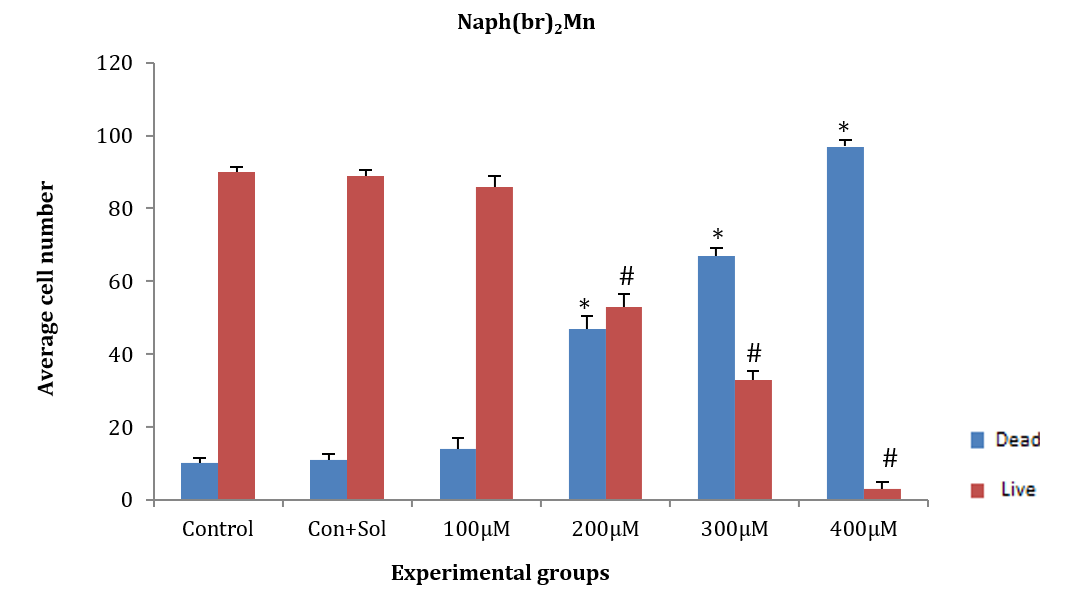

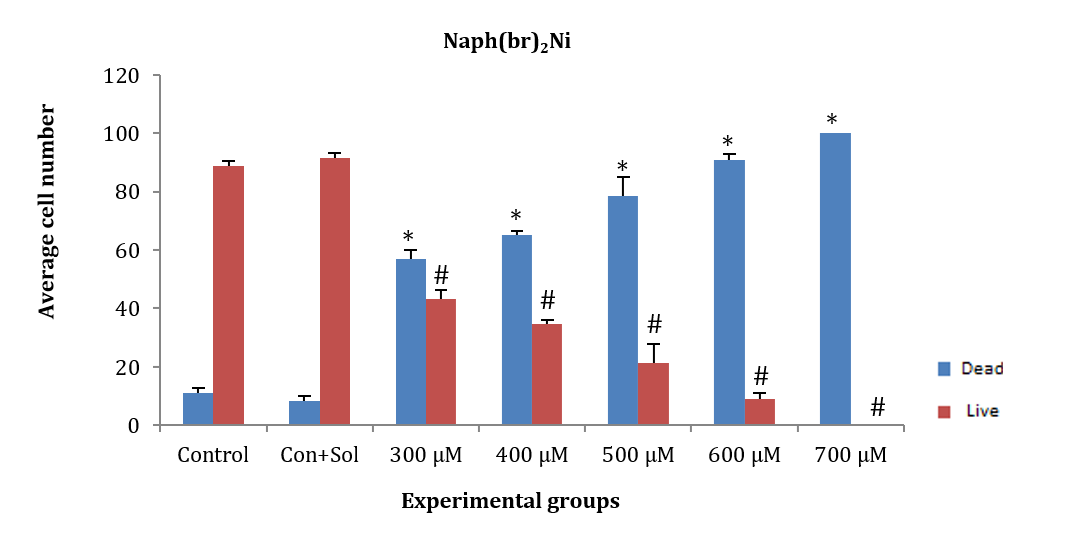

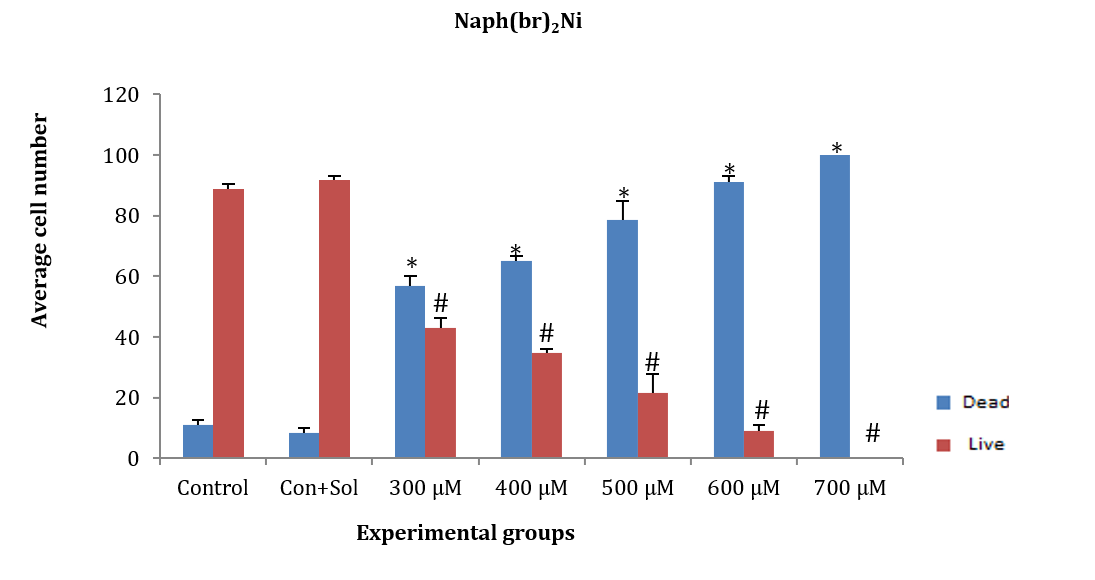

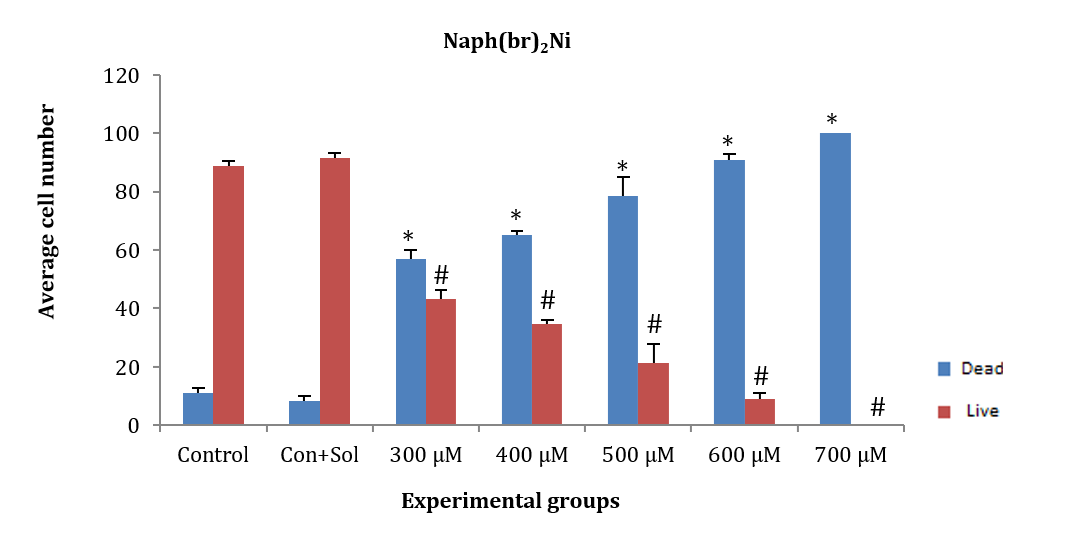

ASCs were treated with naph(br)2Ni at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM for 24 hours. The average number of dead and alive cells at all tested concentrations showed a significant difference compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=300.552, p=0.001). Additionally, a significant difference was observed in the average number of dead and alive cells among the studied groups, except for the 300µM concentration (p<0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of different concentrations of naph(br)Ni on adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) after 24 hours.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells comared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells comared to the control and control+solvent groups.

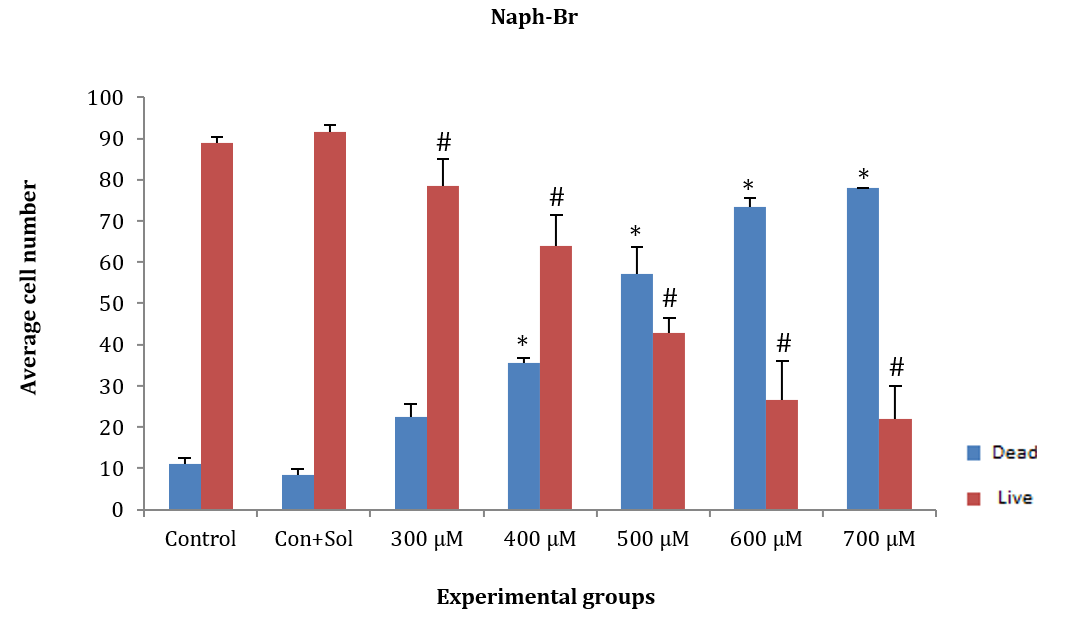

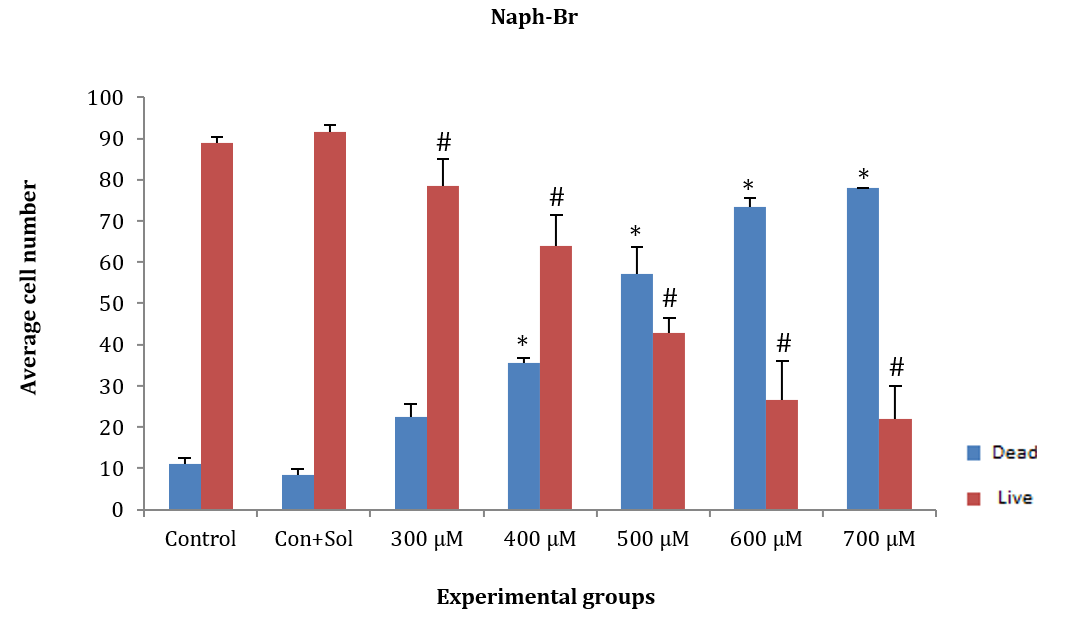

ASCs were treated for 24 hours with naph-Br at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. The average number of dead and alive cells at concentrations of 400, 500, 600, and 700µM showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=171.202, p=0.001). However, the average number of dead and alive cells at the 300µM concentration showed no significant difference compared to the control and control+solvent groups. Additionally, a significant difference was observed between live and dead cells at all concentrations except for 500µM (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of different concentrations of naph-Br on adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) after 24 hours.

* Significant difference in the average number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the average number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

HepG2 cancer cells were treated for 24 hours with naph(br)2Mn at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, and 400µM. The average number of live and dead cells at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400µM significantly decreased compared to the control and control+solvent groups [F (4, 10)=164.997, p=0.001]. However, the average number of dead and alive cells at the 300µM concentration did not show a significant difference compared to the control and control+solvent groups. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the average number of dead and alive cells at the 200µM concentration compared to others (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effect of different concentrations of the chemical substance naph(br)2Mn on HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

HepG2 cancer cells were treated for 24 hours with the chemical substance naph(br)2Ni at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. The average number of dead and alive cells at all tested concentrations showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=140.530, p=0.001). Additionally, the average number of dead and alive cells in each group of concentrations showed a significant difference, except for the 300µM concentration. At the 700µM concentration, more than 98% of the cells died after exposure to the chemical for 24 hours, with only a few cells surviving. Therefore, the 700µM concentration was not considered appropriate for further research (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effect of different concentrations of the chemical substance naph(br)2Ni on HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

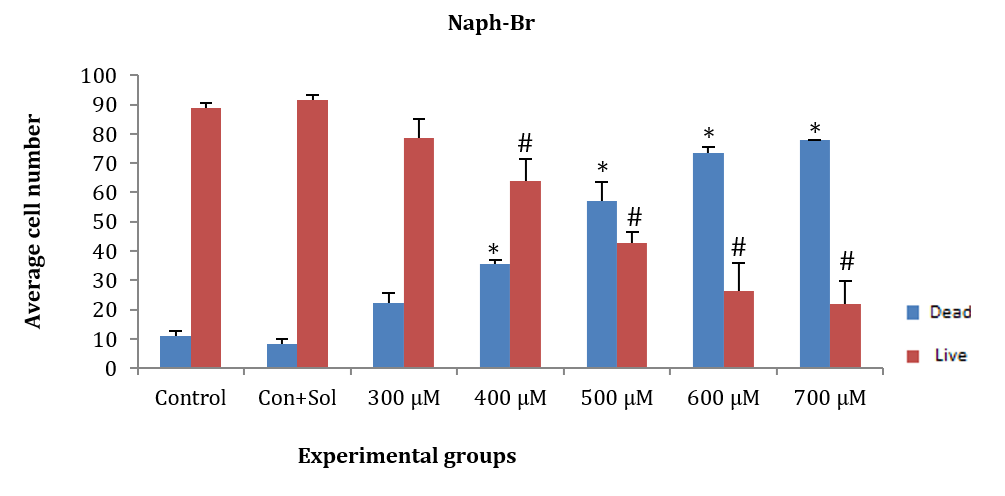

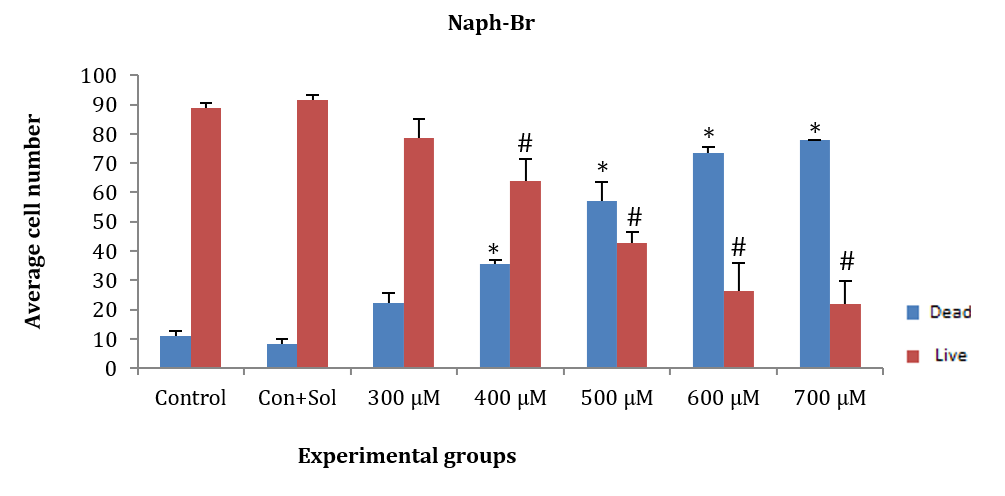

HepG2 cancer cells were treated for 24 hours with naph(br) at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. The average number of dead and alive cells at concentrations of 400, 500, 600, and 700µM showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=35.4, p=0.001). However, no significant difference was observed at the 300µM concentration compared to the control and control+solvent groups. The number of dead and alive cells in each concentration did not show any significant difference from one another, except for the 500µM concentration (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effect of different concentrations of naph(br) on HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent control groups.

In addition, 15,000 ASCs and HepG2 cancer cells were cultured in a 96-well plate in each well until the density reached 40-50%, after which the drug was added at specific concentrations. The proliferation rate of HepG2, adipose, and cancer mesenchymal stem cells was evaluated using the MTT test 24 hours after the addition of chemicals at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. This assessment involved measuring the absorbance of light at 450 nm half an hour after adding the WST1 marker at a rate of one microliter per hour.

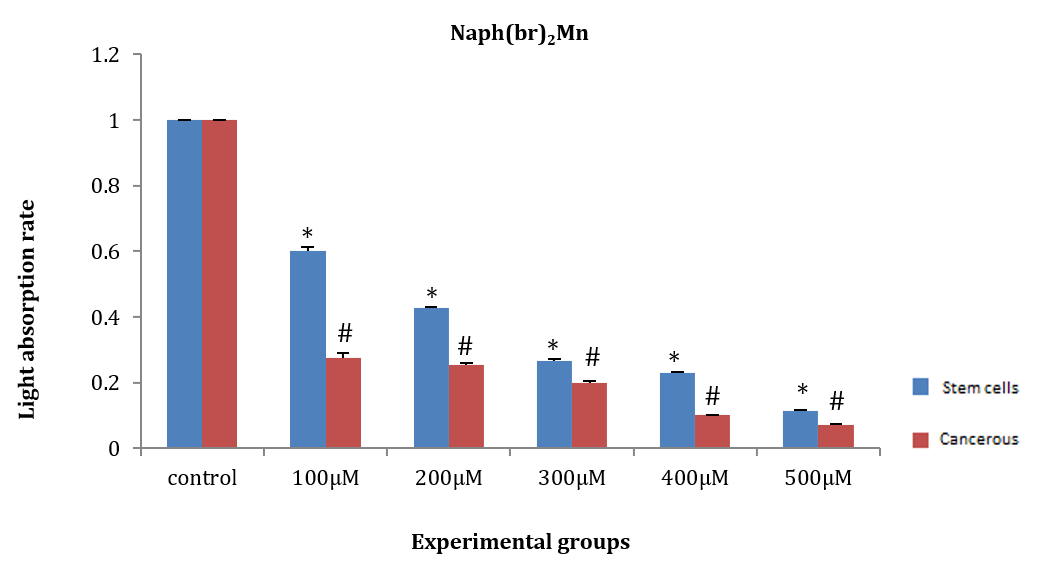

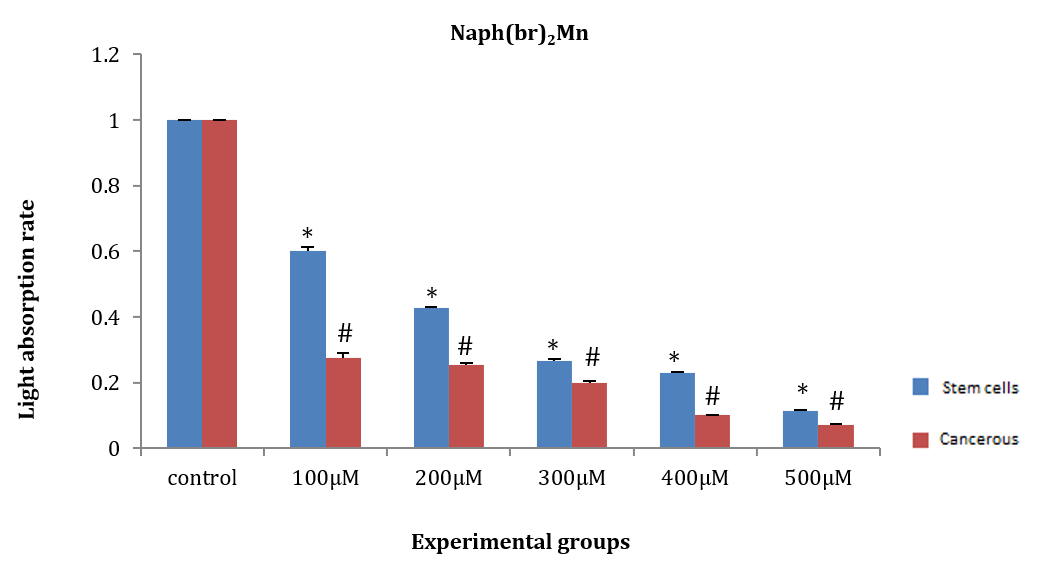

ASCs and HepG2 cells were treated for 24 hours with naph(br)2Mn at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. Subsequently, the WST1 indicator substance was added, and the amount of light absorption was measured at 450nm. The amount of light absorption in all groups of ASCs (F (5, 12)=17.99, p=0.003) and HepG2 cancer cells (F (5, 12)=110.97, p=0.008) showed a significant decrease compared to the control group. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the amount of light absorption between ASCs and HepG2 cancer cells after induction with concentrations of 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. However, the amount of light absorption at concentrations of 400 and 500µM in both HepG2 cells and ASCs showed a significant difference compared to the 100 and 200µM groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effect of naph(br)2Mn on the amount of light absorption of adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) and HepG2 cancer stem cells.

* Significant difference in the amount light absorption rate of ASCs compared to the control group.

# Significant difference in the amount of light absorption rate of HepG2 cancer cells compared to the control group.

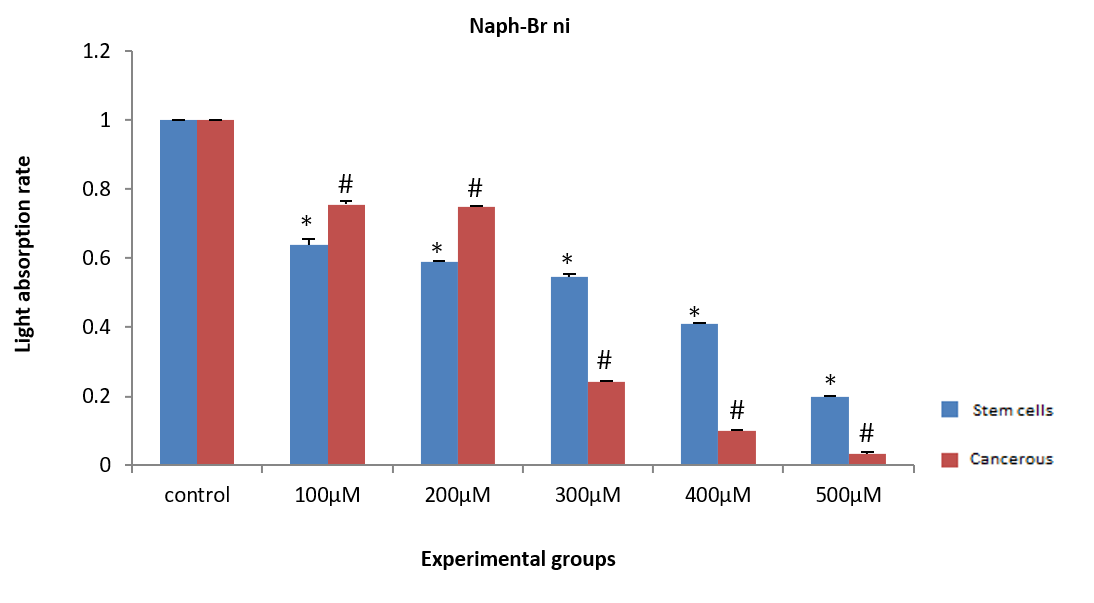

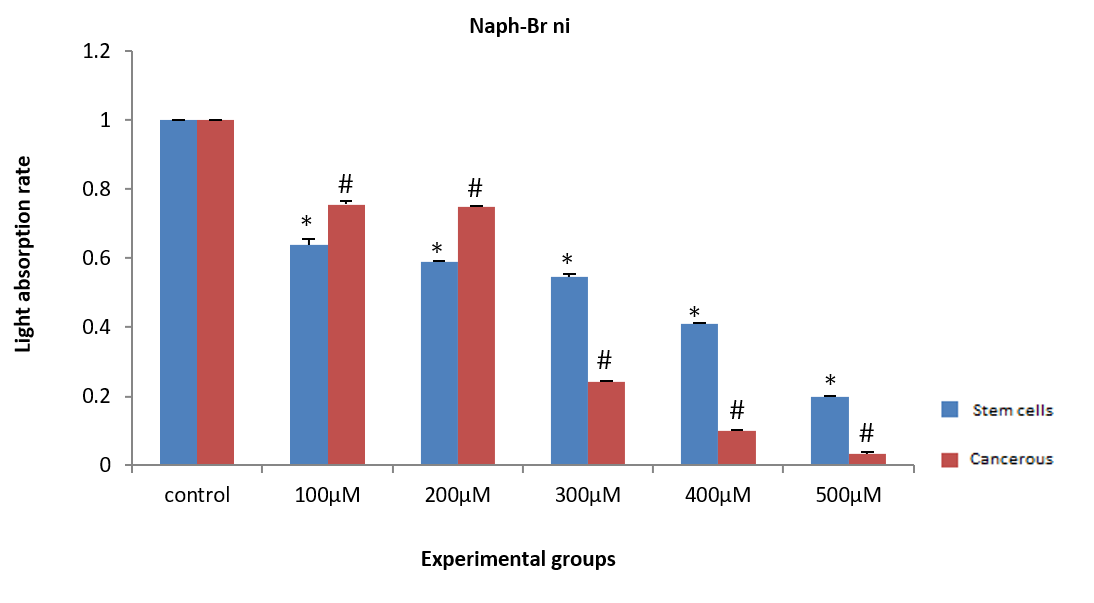

ASCs and HepG2 cancer cells were treated with naph(br)2Ni for 24 hours at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. Then, the WST1 marker was added, and the amount of light absorption at 450nm was measured after half an hour. The amount of light absorption in all groups of ASCs (F (5, 12)=30.99, p=0.02) and HepG2 cancer cells (F (5, 12)=146.97, p=0.01) exhibited a significant decrease compared to the control group. Additionally, at concentrations of 100 and 200µM, there was no significant difference in the amount of light absorption between ASCs and HepG2 cells (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Effect of different concentrations of naph(br)2Ni on the light absorption rate of adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) and HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the light absorption rate of ASCs compared to the control group.

# Significant difference in the light absorption rate of HepG2 cells compared to the control group.

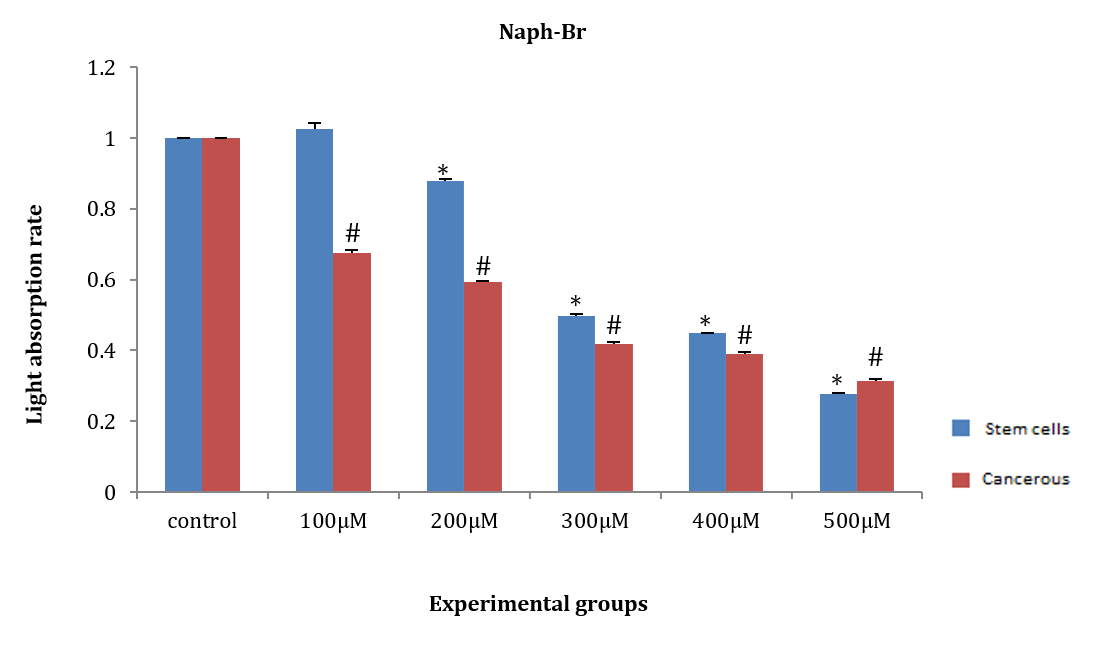

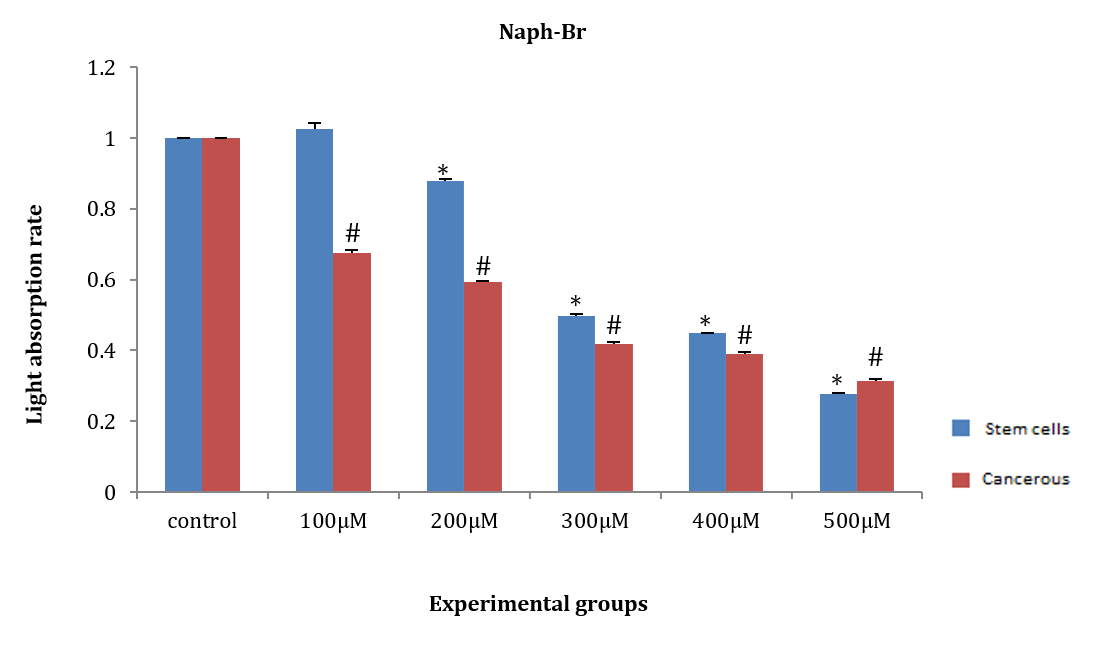

ASCs and HepG2 cells were induced with naph(br) at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM for 24 hours. Then, WST1 was added, and the amount of light absorption at 450nm was measured after half an hour. The amount of light absorption of HepG2 cancer cells at all concentrations showed a significant decrease compared to the control group (p<0.05). However, a significant difference in light absorption was observed in ASCs at the 300, 400, and 500µM concentrations compared to the control group (F (5, 12)=46.1, p=0.00). Additionally, the amount of light absorption in ASCs and HepG2 cells did not show any significant difference at the three mentioned concentrations (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Effect of naph(br) on the amount of light absorption of adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) and HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the absorption rate of ASCs compared to the control group.

# Significant difference in the amount of light absorption of HepG2 cells compared to the control group.

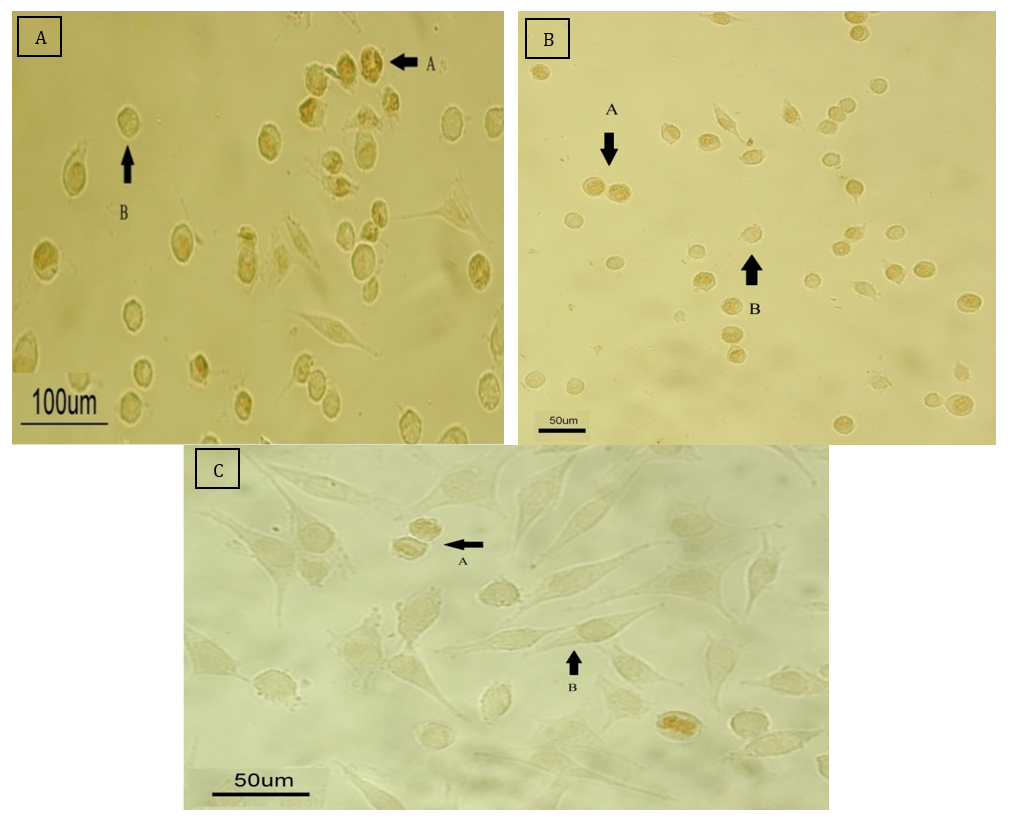

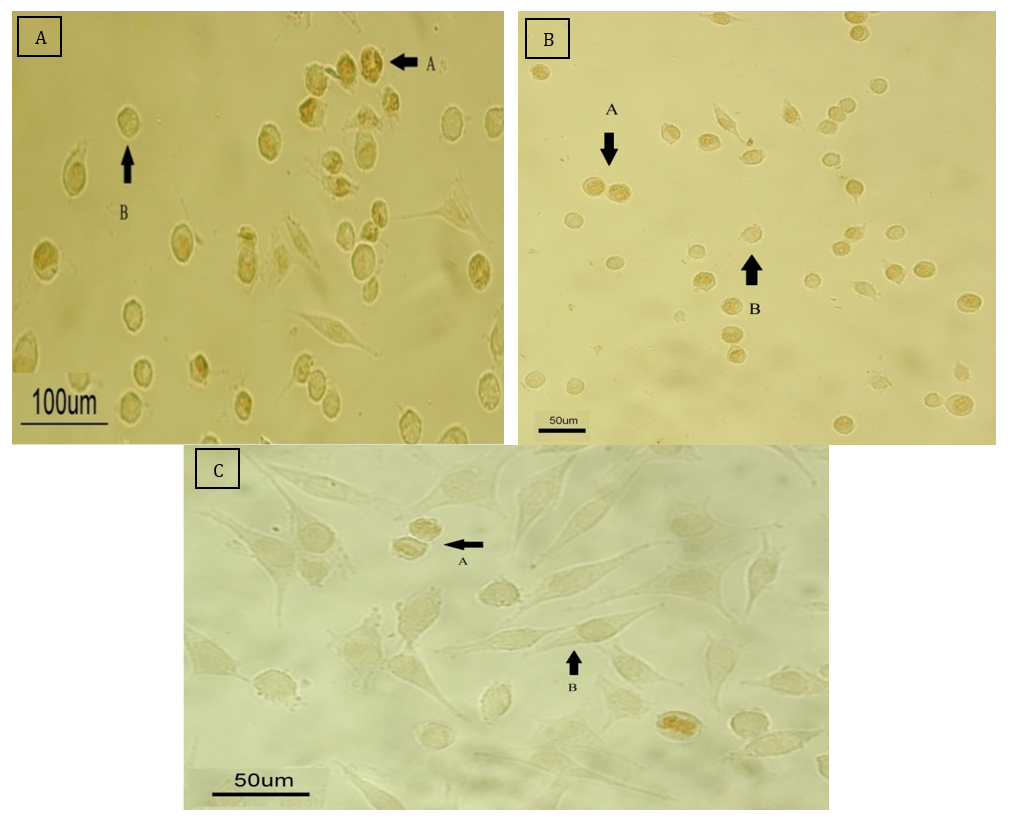

After 24 hours, ASCs and HepG2 cells were treated with three tested chemicals at concentrations of 200 and 300µM. The Ki-67 test was performed according to the instructions outlined in the materials and methods, and the results confirmed the data from the previous two tests. The chemicals significantly reduced the levels of the nuclear protein Ki-67, leading to a decrease in cell proliferation compared to the control group. When observed under a light microscope, the number of stained nuclei showed a significant decrease compared to the control group (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Microscopic assessment of cell proliferation with the KI-67 marker.

A: Control group that did not receive any drug.

B: The group treated with the drug at a concentration of 200μM.

C: The group treated with the drug at a concentration of 300μmol.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to determine the apoptotic effect of Schiff base compounds derived from 2-hydroxynaphthaldehyde and 2-chloroethylamine, as well as manganese complexes, on HepG2 cells compared to ASCs. Cancer has become a major health concern in many countries [43]. The two main factors contributing to the development of cancer are genetic factors, such as gene mutations, and environmental factors, such as lifestyle choices [44]. Globally, cancer was responsible for 7.6 million deaths and accounted for 13% of deaths worldwide in 2008 [45]. Approximately 7 million people die from cancer annually, and it is estimated that 16 million people will develop cancer each year by 2020 [46].

Today, cancer is treated using various methods. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are the primary approaches to cancer treatment [47]. Chemotherapy is a critical component of cancer treatment; however, its effectiveness is limited due to the lack of selectivity between tumor cells and healthy cells, which results in insufficient concentrations of the drug reaching the tumor cells. Consequently, healthy cells are also affected by the drug, and drug-resistant tumor cells may develop [48]. Nevertheless, several strategies have been proposed, including alternative formulations, such as liposomes, modification of resistance, antibodies, gene therapy, and targeted therapy [49].

Targeted treatments can be a suitable alternative to chemotherapy drugs. While chemotherapy drugs affect cell division, they impact not only cancer cells but also normal cells, such as those in the digestive epithelium. Individuals undergoing chemotherapy may experience skin problems, digestive issues, anemia, dizziness, weakness, and lethargy. In contrast, targeted therapies can selectively affect only the targeted cancer cells, making them a promising alternative to chemotherapy. Despite the use of treatment methods such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the survival rate among cancer patients remains low, indicating the ineffectiveness of these treatment options. Poor outcomes in cancer can be attributed to factors such as the lack of early diagnostic methods, the high prevalence of tumor recurrence in patients at advanced stages, and the absence of effective treatments for tumor metastasis to other areas [50].

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a liver tumor recognized as the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths [51]. This disease is often diagnosed at advanced stages, with an average survival rate of 6 to 20 months [52]. Its incidence varies by geographical region and race, with higher prevalence in Asia, Africa, and developing countries. This disparity is primarily due to the higher rates of hepatitis B and C in these areas [53]. Currently, the treatment of liver tumors poses a significant challenge due to the lack of chemosensitivity (expression of drug resistance genes) and liver dysfunction, which disrupts drug delivery [54].

Regenerative medicine is the newest branch of medical science, focused on the functional reconstruction of specific tissues or organs in patients with severe injuries, specialized chronic diseases, or those who have lost tissue due to surgery. At this stage, the body cannot perform its regenerative response [55]. The discovery of stem cells in 1963 by Becker et al. has opened up unlimited opportunities as progenitor cells for the treatment of various diseases [56]. Stem cells can be transplanted into all tissues and organs, playing different roles in disease progression, recovery, and tissue regeneration. They are classified into four groups, including totipotent, pluripotent, multipotent, and unipotent [54].

The characteristics of an ideal stem cell for use in regenerative medicine include abundant availability and ease of extraction with minimal pain and tissue damage, high differentiation ability while maintaining self-renewal, and the possibility of autologous or allogeneic transplantation without concerns about transplant rejection [57]. Thus, fat-derived mesenchymal stem cells have been identified as an ideal alternative source due to their advantages, including high proliferation under laboratory culture conditions and the ability to be stored in frozen form [58]. These cells are multipotent, meaning they can differentiate into various types of cells, including chondrocytes, osteocytes, adipocytes, and neurons [59].

In 1990, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were first utilized in clinical applications to study their safety and efficacy. MSCs were initially employed in the treatment of hematological malignancies [60]. Today, MSCs are used to treat heart diseases, inflammatory diseases, spinal cord injuries, liver diseases, brain injuries, myocardial infarction, and cancer, owing to their safety [61].

Schiff bases are specialized organic chemistry scaffolds synthesized from the condensation reaction of the carbonyl functional group with amines. These molecules exhibit antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties. Studies suggest that when Schiff bases form metal complexes with transition metals, they display enhanced anticancer properties [62].

Successful drug treatments target specific cells with minimal clinical effects on the host. Cancer remains a major health concern, leading to increased focus on non-platinum substances in chemotherapy research. Metal complexes derived from titanium, gallium, germanium, palladium, gold, cobalt, ruthenium, and tin are being investigated as alternatives to platinum due to their lower toxicity. The therapeutic goal in cancer treatment is the selective targeting of tumor cells, as uncontrolled cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis contribute to the development and progression of malignant tumors [63].

The anticancer properties of various Schiff base compounds and their metal complexes have been investigated. In 2013, Amer et al. studied a series of Schiff base complexes containing Cu(II) derived from purine and triazole on MCF7, liver (HepG2), and colon (HCT116) cancers. They demonstrated that the compound significantly reduce the survival and viability of MCF7, HCT116, and HepG2 cells [64].

Jevtović et al. assessed the effect of Schiff base compounds containing copper derived from pyridoxal-semicarbazide on MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells and showed that there is a decrease in the survival and viability of the experimental cells at both 24 and 72 hours [65].

In 2014, Gwaram et al. investigated metal-Schiff base complexes derived from morpholine (specifically, 2-hydroxyacetophenone with 4-(2-aminoethyl) morpholine) on MCF7 cells over periods of 24 and 48 hours, showing a decrease in cell proliferation and survival [66].

In 2013, Zuo et al. investigated the effect of Schiff amino acid bases containing copper metal on MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and prostate (PC-3) cancer cells. They showed that these amino acid Schiff bases can reduce cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in cancer cells [36].

We used three Schiff base complexes, including Naph(br)₂Mn, Naph(br)Ni, and Naph-Br, at seven concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. Initially, as the concentration of the Schiff base complexes increased, the proliferation of cancer and stem cells decreased at 24 hours compared to the control group. Additionally, higher concentrations of the complexes resulted in decreased cell survival and increased cell death. Some toxicity was observed at the concentration of 100µM, but the number of dead cells continued to increase in both mesenchymal and cancer stem cells (HepG2). No significant difference was noted in the average number of living cells compared to the control group. Conversely, the number of dead cells at concentrations of 600 and 700µM exceeded 98%, with only a small number surviving. Concentrations of 200 and 300µM in the Naph(br)₂Mn compound were deemed suitable doses, while suitable doses for naph-Br and Naph(br)₂Ni were estimated at 300 and 400µM, respectively.

The anticancer properties of various Schiff base compounds and their metal complexes have been investigated. In 2013, Amer et al. [64] studied a series of Schiff base complexes containing Cu(II) derived from purine and triazole on MCF7, liver (HepG2), and colon (HCT116) cancers. They demonstrated that the compound reduced the survival and viability of MCF7, HCT116, and HepG2 cells.

In another experiment, Jevtović et al. [65] assessed the effect of Schiff base compounds containing copper derived from pyridoxal-semicarbazide on MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. They indicated that there is a decrease in the survival and viability of the experimental cells at both 24 and 72 hours. In 2014, Gwaram et al. [66] investigated metal-Schiff base complexes derived from morpholine (specifically, 2-hydroxyacetophenone with 4-(2-aminoethyl) morpholine) on MCF7 cells over 24 and 48 hours, revealing a decrease in cell proliferation and survival.

In 2013, Zuo et al. [36] examined the effect of Schiff amino acid bases containing copper metal on MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and prostate (PC-3) cancer cells, indicating that these amino acid Schiff bases can reduce cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in cancer cells.

The observed effects at concentrations ranging from 200 to 500µM suggest a dose-dependent relationship, indicating the efficacy of these compounds in targeting cancer cells. This research highlights the promising role of Schiff base compounds as adjunctive anti-cancer agents and their potential for incorporation into novel cancer treatment strategies.

The ability of Schiff base compounds to reduce the proliferation rate of cancer cells and increase mortality compared to control groups underscores their therapeutic potential. These compounds exhibit cytotoxic effects on cancer cells, providing a mechanism for suppressing tumor growth and promoting cell death. The results suggest that Schiff base compounds may have specific molecular targets within cancer cells, making them valuable candidates for further investigation and development in cancer therapy.

It can be concluded that Schiff-base compounds can serve as valuable additions to existing anti-cancer treatments. Their demonstrated ability to impede cancer cell proliferation and induce cell death at multiple concentrations signifies their versatility and potency in combating cancer. By incorporating these compounds into treatment regimens, healthcare providers may enhance the efficacy of current therapies and potentially overcome drug resistance in cancer patients.

The research outcomes provide a solid foundation for exploring the clinical applications of Schiff-base compounds in cancer treatment. Health policymakers should consider integrating these compounds into oncology protocols to improve patient outcomes and broaden the therapeutic options available. Collaborative efforts among researchers, clinicians, and policymakers are essential to facilitate the translation of these findings into practical interventions that can benefit cancer patients worldwide.

In light of these compelling results, health policymakers must prioritize the evaluation and potential implementation of Schiff-base compounds in cancer care. By investing in further research, clinical trials, and regulatory assessments, policymakers can expedite the approval and accessibility of these compounds for cancer patients. Embracing innovation in cancer treatment through the utilization of Schiff base compounds represents a proactive approach to advancing oncology practices and addressing the evolving challenges posed by cancer.

In conclusion, the findings on the anti-cancer properties of Schiff base compounds underscore their significance as promising therapeutic agents in oncology. Health policymakers are encouraged to support the development and integration of these compounds into cancer treatment protocols to enhance patient care and foster advancements in the field of oncology. By harnessing the potential of Schiff base compounds, healthcare systems can strive toward more effective, personalized, and comprehensive cancer management strategies.

Conclusion

Schiff base compounds inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells and induce apoptosis at multiple concentrations, demonstrating their versatility and efficacy in combating cancer.

Acknowledgments: The authors appreciate the manager and staff of the Faculty of Biology for their collaboration in this research.

Ethical Permissions: This article was approved by the Faculty of Biology, Damghan University, Iran (IR.DU.REC.1400.009).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Wennas ON (First Author), Methodologist (25%); Haji Ghasem Kashani M (Second Author), Main Researcher (30%); Abiri E (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (25%); Altememy D (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was done with the financial support of the Faculty of Biology, Damghan University.

Cancer refers to a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation, invasion of cells into adjacent tissues, and metastasis in more advanced stages. Disturbances in cell behavior arise from changes in gene sequences or epigenetic modifications [1-3]. Initially, the cell mass resulting from the uncontrolled proliferation of cells with a high growth rate, without invasion or metastasis, is referred to as a tumor. When the cell mass loses proper organization, the rate of cell proliferation increases, and the cells acquire the ability to invade and metastasize. At this stage, it is termed cancer [4, 5].

Most of the factors that contribute to cancer are associated with DNA sequence changes or mutations. Therefore, like all genetic diseases, cancers are caused by alterations in DNA. Genes involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, when deregulated, can lead to a cancer phenotype. The genetic changes that characterize cancer are sometimes the result of inherited defects [5-8].

Cancer cells in tumor tissue can self-renew and differentiate into specialized cells, and they also exhibit resistance to chemotherapy. The exact origin of these cells is not fully understood; this does not imply that cancer stem cells derive from stem cells. Instead, due to the accumulation of mutations in these cells, they exhibit a phenotype similar to that of stem cells. Cancer stem cells can give rise to different types of cancer cells within a tumor sample, distinguishing them from other cancer cells, which is why they are referred to as tumorigenic [8, 9]. Cancer is not necessarily caused by cancer stem cells, although the terms “cells that lead to cancer” and “cancer stem cells” are sometimes used interchangeably [10].

Currently, the use of stem cells in the treatment of various types of cancers and diseases is under consideration. One notable application of stem cells is in the treatment of liver cancer. Liver cancer begins in one part of the liver and can spread to other areas. Histologically, 80% of liver cancers are classified as hepatocellular carcinoma [11, 12]. Liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. In 2002, 600,000 people in developing countries were diagnosed with liver cancer [13]. The HepG2 cell line is a type of liver cancer cell line that, morphologically, demonstrates high proliferative capacity and low differentiation ability under laboratory conditions [14, 15].

Mesenchymal stem cells are defined as multipotent stem cells capable of self-renewal and proliferation, with the ability to differentiate into at least three mesodermal lineages in a laboratory environment, including chondrocytes, adipocytes, and osteoblasts. They can also differentiate into other cell types from the endodermal and mesodermal lineages, such as liver hepatocytes and neurons [16, 17]. Although these cells are found in most tissues, including the liver, muscle, lung, umbilical cord, and amniotic fluid, they can be specifically harvested from bone marrow and adipose tissue [18, 19].

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue (adipose tissue-derived stem cells: ADSCs or ASCs) can be extracted from fat tissue through liposuction. These cells can self-renew and differentiate into mesodermal lineages such as cartilage, adipose tissue, and bone [20]. The surface markers of ASCs are similar to those of stem cells derived from bone marrow, including CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD44, CD146, and CD166 [21]. However, they can be distinguished by the expression of the CD34 marker [22]. These cells can express and secrete various factors, including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and anti-inflammatory biomarkers associated with the development and progression of cancer, such as IGF, FGF, HGF, TGF-β, VEGF, IL-8, and IL-10 [23].

ASCs can be used in the treatment of various diseases, including autoimmune diseases, MS, diabetes, upper respiratory system disorders, cardiovascular diseases, brain and spinal cord surgeries, wound healing, and cancer [21, 22, 24]. Currently, ASC is a valuable tool in cell therapy that is being considered for cancer treatment [25]. Numerous studies have investigated the role of ASC in cancer treatment, and whether ASCs support or suppresse the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells remains a topic of debate [26, 27].

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death process governed by distinct biochemical and genetic pathways that play a crucial role in tissue development and homeostasis. It also serves as a defense mechanism that eliminates unwanted or damaged cells [28]. In the early stages of apoptosis, cells become rounded, lose their connections with surrounding cells, and shrink. In the later stages, the DNA condenses and is fragmented by endonucleases [29, 30]. Apoptosis occurs 20 times faster than mitosis, maintaining a balance between the increase and decrease of cell populations. Regulators of apoptosis directly or indirectly control the activity of caspases, which are cysteine proteases that play a key role in executing apoptosis by cleaving substrates at specific aspartate residues [31]. Several environmental factors can activate or inhibit apoptosis. Activators of apoptosis include TNF-α, Fas ligands, TGF-β, BAX, other pro-apoptotic family members (such as Bcl-2), and glucocorticoids [32-34].

Schiff bases are compounds formed through condensation reactions between a carbonyl group and an amine. These compounds possess a basic nature due to a pair of non-bonding electrons on nitrogen and act as ligands with Lewis acids, primarily metal ions. Open-Schiff complexes exhibit various structures depending on the coordinating metal used. For instance, cobalt and nickel ions tend to form square planar and octahedral complexes, while copper ions typically form tetrahedral structures. Many Schiff base complexes are utilized as drugs with a wide range of biological properties against bacteria, fungi, microbes, certain tumors, and cancer [35, 36].

In recent years, the vanadium-Schiff base complex has garnered increasing attention from chemists. Due to its biological role, vanadium complexes are involved in haloperoxidation, nitrogen fixation, phosphorization, mimicking the role of insulin, inhibiting tumor growth, and regulating glycogen metabolism, among other functions [37, 38].

Schiff base complexes of copper and nickel (Cu and Ni complexes) derived from 2,6-diacetylpyridine and 2-pyridine carboxaldehyde exhibit antibacterial activity against various bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [39, 40]. Additionally, anti-cancer compounds containing copper as a central metal have been researched. Copper-Schiff base complexes have shown promise in cancer treatment, with [Cu(pyimpy)Cl2] identified as the most effective combination [41, 42].

Considering the importance of the toxicity and apoptotic properties of anticancer compounds, only agents with minimal apoptotic and toxic effects on cancer cells can be introduced as ideal anticancer drugs. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the apoptotic effect of Schiff base compounds derived from 2-hydroxynaphthaldehyde and 2-chloroethylamine, as well as manganese complexes, on HepG2 cells compared to ASCs. Since these tested materials were prepared at the Faculty of Chemistry of Damghan University in Iran, the researchers felt it necessary to investigate and report the anticancer properties and apoptotic effects of these materials.

Materials and Methods

In this experimental research, three chemicals—Bis(2-{(E)-[(2-Bromoethyl)imino(methyl)]}6-methoxyphenolate) manganese(II) (naph(br)2mn), Bis(2-{(E)-[(2-bromoethyl)imino(methyl)]}6-methoxyphenolate) nickel(II) (naph(br)2Ni), and the Schiff base ligand 2-{(E)-[(2-bromoethyl)imino(methyl)]}6-methoxyphenol (naph-Br))—were synthesized by researchers at the Faculty of Chemistry of Damghan University in Iran under the guidance of respected professors.

Experimental groups included a control group, in which the cells were cultured in culture medium and serum without the presence of chemicals, th control group+solvent, in which, in addition to culture medium and serum, the maximum amount of solvent present in the treatment group was also added, and the treatment group, in which the cells were exposed to the desired chemical substances at the specified concentrations.

This study adheres to internationally accepted standards for animal research, following the 3Rs principle. The ARRIVE guidelines were employed for reporting experiments involving live animals, promoting ethical research practices.

The laboratory studies involved the extraction and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from rat adipose tissue, the culture of HepG2 cancer cells, the investigation of the viability of mesenchymal stem cells and HepG2 cancer cells in the presence of the drug using the proliferation test and cell counting, the examination of the effect of Schiff open complexes on the proliferation rate of mesenchymal stem cells and HepG2 cancer cells using the MTT method, and the assessment of cell proliferation rates through the Ki67 immunocytochemistry method.

Adipose tissue was isolated from a female rat from the area between the two scapulae under sterile conditions. After mechanical digestion and chemical digestion with collagenase enzyme, 2 ml of culture medium (DMEM+10% serum) was added, followed by centrifugation. The tissue was then transferred to a culture flask containing DMEM+10% serum and incubated.

Cancer cells were obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. The cells were cultured in an incubator (temperature 37°C, humidity 95%, and CO2 5%), with the medium changed every 48 hours, using DMEM culture medium containing 10% FBS serum [41, 42]. Passage was performed when the cells reached 80% confluence in the flask. The doubling time of the cancer cell population is approximately 38 hours.

Cell viability and proliferation were evaluated using a Neubauer slide. To count the number of cells, the cells were first thoroughly trypsinized, and then the cell suspension was transferred into a Falcon tube and centrifuged. The supernatant was discarded, and fresh culture medium was added to the cell pellet, which was then pipetted thoroughly. Next, 10µl of this suspension were placed on a Neubauer slide, and a cover slip was gently positioned on top for observation with a light microscope. After counting the cells in the four corners of the Neubauer slide, the following formula was used to calculate the number of cells in a volume of 3ml:

The doubling time of ASC and HepG2 cancer cells was evaluated using the MTT assay. Mesenchymal stem cells and HepG2 cancer cells were cultured individually at a density of 15,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate with 100µl of DMEM culture medium and 10% serum until the density reached 40-50%. The proliferation rate of HepG2 mesenchymal stem cells treated with the desired chemicals at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µmol over 24 hours was then investigated. Subsequently, 10 µl of the WST-1 kit solution was added to the culture medium of the cells. At time intervals of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours after adding the WST-1 kit, the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450nm using the ELISA reader (BioTek).

HepG2 mesenchymal stem cells were cultured, and when the cell density reached 40-50%, the chemicals were added. After 24 hours, anti-Ki-67 immunohistochemistry was performed using the primary antibody (abcam-ab833) and the secondary antibody (Goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP).

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 software. Statistical calculations were performed to investigate differences between groups using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for behavioral data. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Finally, corresponding graphs were created using Excel.

Findings

HepG2 cells exhibited a high proliferative capacity in the laboratory setting. They displayed a polygonal and elongated appearance. In contrast, the adipose stem cells appeared pseudo-fibroblastic, with lower proliferative ability and a spindle-shaped, elongated appearance. Additionally, they had a lower density (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Morphological examination of HepG2 cells; A: HepG2 cancer cells; B: Adipose stem cells from rats.

ASC and HepG2 cancer cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 15,000 cells per well in DMEM with 10% serum until the cell density reached 40-50%. The cells were then treated with the desired chemicals at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM for 24 hours. The survival rate, as well as the rate of proliferation of stem and cancer cells, were investigated.

ASCs were treated for 24 hours with the chemical substance naph(br)2Mn at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, and 400µM. There was no significant difference in the average number of dead and alive cells at the concentration of 100µM compared to the control and control+solvent groups. In contrast, the number of dead and alive cells at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400µM showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=285.14, p=0.001). In the 400µM group, more than 98% of the cells died after exposure to the chemical for 24 hours, with only a few surviving. Therefore, this concentration was not deemed suitable for further research. Additionally, at the 200µM concentration, there was no significant difference between the average numbers of dead and live cells; however, at the 300µM concentration, a significant difference was observed between dead and live cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of naph(br)2Mn on adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) after 24 hours.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control+solvent group.

# Significant difference in mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

ASCs were treated with naph(br)2Ni at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM for 24 hours. The average number of dead and alive cells at all tested concentrations showed a significant difference compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=300.552, p=0.001). Additionally, a significant difference was observed in the average number of dead and alive cells among the studied groups, except for the 300µM concentration (p<0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of different concentrations of naph(br)Ni on adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) after 24 hours.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells comared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells comared to the control and control+solvent groups.

ASCs were treated for 24 hours with naph-Br at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. The average number of dead and alive cells at concentrations of 400, 500, 600, and 700µM showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=171.202, p=0.001). However, the average number of dead and alive cells at the 300µM concentration showed no significant difference compared to the control and control+solvent groups. Additionally, a significant difference was observed between live and dead cells at all concentrations except for 500µM (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of different concentrations of naph-Br on adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) after 24 hours.

* Significant difference in the average number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the average number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

HepG2 cancer cells were treated for 24 hours with naph(br)2Mn at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, and 400µM. The average number of live and dead cells at concentrations of 200, 300, and 400µM significantly decreased compared to the control and control+solvent groups [F (4, 10)=164.997, p=0.001]. However, the average number of dead and alive cells at the 300µM concentration did not show a significant difference compared to the control and control+solvent groups. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the average number of dead and alive cells at the 200µM concentration compared to others (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effect of different concentrations of the chemical substance naph(br)2Mn on HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

HepG2 cancer cells were treated for 24 hours with the chemical substance naph(br)2Ni at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. The average number of dead and alive cells at all tested concentrations showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=140.530, p=0.001). Additionally, the average number of dead and alive cells in each group of concentrations showed a significant difference, except for the 300µM concentration. At the 700µM concentration, more than 98% of the cells died after exposure to the chemical for 24 hours, with only a few cells surviving. Therefore, the 700µM concentration was not considered appropriate for further research (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effect of different concentrations of the chemical substance naph(br)2Ni on HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

HepG2 cancer cells were treated for 24 hours with naph(br) at concentrations of 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. The average number of dead and alive cells at concentrations of 400, 500, 600, and 700µM showed a significant decrease compared to the control and control+solvent groups (F (5, 12)=35.4, p=0.001). However, no significant difference was observed at the 300µM concentration compared to the control and control+solvent groups. The number of dead and alive cells in each concentration did not show any significant difference from one another, except for the 500µM concentration (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effect of different concentrations of naph(br) on HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the mean number of dead cells compared to the control and control+solvent groups.

# Significant difference in the mean number of live cells compared to the control and control+solvent control groups.

In addition, 15,000 ASCs and HepG2 cancer cells were cultured in a 96-well plate in each well until the density reached 40-50%, after which the drug was added at specific concentrations. The proliferation rate of HepG2, adipose, and cancer mesenchymal stem cells was evaluated using the MTT test 24 hours after the addition of chemicals at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. This assessment involved measuring the absorbance of light at 450 nm half an hour after adding the WST1 marker at a rate of one microliter per hour.

ASCs and HepG2 cells were treated for 24 hours with naph(br)2Mn at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. Subsequently, the WST1 indicator substance was added, and the amount of light absorption was measured at 450nm. The amount of light absorption in all groups of ASCs (F (5, 12)=17.99, p=0.003) and HepG2 cancer cells (F (5, 12)=110.97, p=0.008) showed a significant decrease compared to the control group. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the amount of light absorption between ASCs and HepG2 cancer cells after induction with concentrations of 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. However, the amount of light absorption at concentrations of 400 and 500µM in both HepG2 cells and ASCs showed a significant difference compared to the 100 and 200µM groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effect of naph(br)2Mn on the amount of light absorption of adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) and HepG2 cancer stem cells.

* Significant difference in the amount light absorption rate of ASCs compared to the control group.

# Significant difference in the amount of light absorption rate of HepG2 cancer cells compared to the control group.

ASCs and HepG2 cancer cells were treated with naph(br)2Ni for 24 hours at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM. Then, the WST1 marker was added, and the amount of light absorption at 450nm was measured after half an hour. The amount of light absorption in all groups of ASCs (F (5, 12)=30.99, p=0.02) and HepG2 cancer cells (F (5, 12)=146.97, p=0.01) exhibited a significant decrease compared to the control group. Additionally, at concentrations of 100 and 200µM, there was no significant difference in the amount of light absorption between ASCs and HepG2 cells (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Effect of different concentrations of naph(br)2Ni on the light absorption rate of adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) and HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the light absorption rate of ASCs compared to the control group.

# Significant difference in the light absorption rate of HepG2 cells compared to the control group.

ASCs and HepG2 cells were induced with naph(br) at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500µM for 24 hours. Then, WST1 was added, and the amount of light absorption at 450nm was measured after half an hour. The amount of light absorption of HepG2 cancer cells at all concentrations showed a significant decrease compared to the control group (p<0.05). However, a significant difference in light absorption was observed in ASCs at the 300, 400, and 500µM concentrations compared to the control group (F (5, 12)=46.1, p=0.00). Additionally, the amount of light absorption in ASCs and HepG2 cells did not show any significant difference at the three mentioned concentrations (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Effect of naph(br) on the amount of light absorption of adipose tissue stem cells (ASCs) and HepG2 cancer cells.

* Significant difference in the absorption rate of ASCs compared to the control group.

# Significant difference in the amount of light absorption of HepG2 cells compared to the control group.

After 24 hours, ASCs and HepG2 cells were treated with three tested chemicals at concentrations of 200 and 300µM. The Ki-67 test was performed according to the instructions outlined in the materials and methods, and the results confirmed the data from the previous two tests. The chemicals significantly reduced the levels of the nuclear protein Ki-67, leading to a decrease in cell proliferation compared to the control group. When observed under a light microscope, the number of stained nuclei showed a significant decrease compared to the control group (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Microscopic assessment of cell proliferation with the KI-67 marker.

A: Control group that did not receive any drug.

B: The group treated with the drug at a concentration of 200μM.

C: The group treated with the drug at a concentration of 300μmol.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to determine the apoptotic effect of Schiff base compounds derived from 2-hydroxynaphthaldehyde and 2-chloroethylamine, as well as manganese complexes, on HepG2 cells compared to ASCs. Cancer has become a major health concern in many countries [43]. The two main factors contributing to the development of cancer are genetic factors, such as gene mutations, and environmental factors, such as lifestyle choices [44]. Globally, cancer was responsible for 7.6 million deaths and accounted for 13% of deaths worldwide in 2008 [45]. Approximately 7 million people die from cancer annually, and it is estimated that 16 million people will develop cancer each year by 2020 [46].

Today, cancer is treated using various methods. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are the primary approaches to cancer treatment [47]. Chemotherapy is a critical component of cancer treatment; however, its effectiveness is limited due to the lack of selectivity between tumor cells and healthy cells, which results in insufficient concentrations of the drug reaching the tumor cells. Consequently, healthy cells are also affected by the drug, and drug-resistant tumor cells may develop [48]. Nevertheless, several strategies have been proposed, including alternative formulations, such as liposomes, modification of resistance, antibodies, gene therapy, and targeted therapy [49].

Targeted treatments can be a suitable alternative to chemotherapy drugs. While chemotherapy drugs affect cell division, they impact not only cancer cells but also normal cells, such as those in the digestive epithelium. Individuals undergoing chemotherapy may experience skin problems, digestive issues, anemia, dizziness, weakness, and lethargy. In contrast, targeted therapies can selectively affect only the targeted cancer cells, making them a promising alternative to chemotherapy. Despite the use of treatment methods such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the survival rate among cancer patients remains low, indicating the ineffectiveness of these treatment options. Poor outcomes in cancer can be attributed to factors such as the lack of early diagnostic methods, the high prevalence of tumor recurrence in patients at advanced stages, and the absence of effective treatments for tumor metastasis to other areas [50].

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a liver tumor recognized as the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths [51]. This disease is often diagnosed at advanced stages, with an average survival rate of 6 to 20 months [52]. Its incidence varies by geographical region and race, with higher prevalence in Asia, Africa, and developing countries. This disparity is primarily due to the higher rates of hepatitis B and C in these areas [53]. Currently, the treatment of liver tumors poses a significant challenge due to the lack of chemosensitivity (expression of drug resistance genes) and liver dysfunction, which disrupts drug delivery [54].

Regenerative medicine is the newest branch of medical science, focused on the functional reconstruction of specific tissues or organs in patients with severe injuries, specialized chronic diseases, or those who have lost tissue due to surgery. At this stage, the body cannot perform its regenerative response [55]. The discovery of stem cells in 1963 by Becker et al. has opened up unlimited opportunities as progenitor cells for the treatment of various diseases [56]. Stem cells can be transplanted into all tissues and organs, playing different roles in disease progression, recovery, and tissue regeneration. They are classified into four groups, including totipotent, pluripotent, multipotent, and unipotent [54].

The characteristics of an ideal stem cell for use in regenerative medicine include abundant availability and ease of extraction with minimal pain and tissue damage, high differentiation ability while maintaining self-renewal, and the possibility of autologous or allogeneic transplantation without concerns about transplant rejection [57]. Thus, fat-derived mesenchymal stem cells have been identified as an ideal alternative source due to their advantages, including high proliferation under laboratory culture conditions and the ability to be stored in frozen form [58]. These cells are multipotent, meaning they can differentiate into various types of cells, including chondrocytes, osteocytes, adipocytes, and neurons [59].

In 1990, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were first utilized in clinical applications to study their safety and efficacy. MSCs were initially employed in the treatment of hematological malignancies [60]. Today, MSCs are used to treat heart diseases, inflammatory diseases, spinal cord injuries, liver diseases, brain injuries, myocardial infarction, and cancer, owing to their safety [61].

Schiff bases are specialized organic chemistry scaffolds synthesized from the condensation reaction of the carbonyl functional group with amines. These molecules exhibit antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties. Studies suggest that when Schiff bases form metal complexes with transition metals, they display enhanced anticancer properties [62].

Successful drug treatments target specific cells with minimal clinical effects on the host. Cancer remains a major health concern, leading to increased focus on non-platinum substances in chemotherapy research. Metal complexes derived from titanium, gallium, germanium, palladium, gold, cobalt, ruthenium, and tin are being investigated as alternatives to platinum due to their lower toxicity. The therapeutic goal in cancer treatment is the selective targeting of tumor cells, as uncontrolled cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis contribute to the development and progression of malignant tumors [63].

The anticancer properties of various Schiff base compounds and their metal complexes have been investigated. In 2013, Amer et al. studied a series of Schiff base complexes containing Cu(II) derived from purine and triazole on MCF7, liver (HepG2), and colon (HCT116) cancers. They demonstrated that the compound significantly reduce the survival and viability of MCF7, HCT116, and HepG2 cells [64].

Jevtović et al. assessed the effect of Schiff base compounds containing copper derived from pyridoxal-semicarbazide on MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells and showed that there is a decrease in the survival and viability of the experimental cells at both 24 and 72 hours [65].

In 2014, Gwaram et al. investigated metal-Schiff base complexes derived from morpholine (specifically, 2-hydroxyacetophenone with 4-(2-aminoethyl) morpholine) on MCF7 cells over periods of 24 and 48 hours, showing a decrease in cell proliferation and survival [66].

In 2013, Zuo et al. investigated the effect of Schiff amino acid bases containing copper metal on MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and prostate (PC-3) cancer cells. They showed that these amino acid Schiff bases can reduce cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in cancer cells [36].

We used three Schiff base complexes, including Naph(br)₂Mn, Naph(br)Ni, and Naph-Br, at seven concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700µM. Initially, as the concentration of the Schiff base complexes increased, the proliferation of cancer and stem cells decreased at 24 hours compared to the control group. Additionally, higher concentrations of the complexes resulted in decreased cell survival and increased cell death. Some toxicity was observed at the concentration of 100µM, but the number of dead cells continued to increase in both mesenchymal and cancer stem cells (HepG2). No significant difference was noted in the average number of living cells compared to the control group. Conversely, the number of dead cells at concentrations of 600 and 700µM exceeded 98%, with only a small number surviving. Concentrations of 200 and 300µM in the Naph(br)₂Mn compound were deemed suitable doses, while suitable doses for naph-Br and Naph(br)₂Ni were estimated at 300 and 400µM, respectively.

The anticancer properties of various Schiff base compounds and their metal complexes have been investigated. In 2013, Amer et al. [64] studied a series of Schiff base complexes containing Cu(II) derived from purine and triazole on MCF7, liver (HepG2), and colon (HCT116) cancers. They demonstrated that the compound reduced the survival and viability of MCF7, HCT116, and HepG2 cells.

In another experiment, Jevtović et al. [65] assessed the effect of Schiff base compounds containing copper derived from pyridoxal-semicarbazide on MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. They indicated that there is a decrease in the survival and viability of the experimental cells at both 24 and 72 hours. In 2014, Gwaram et al. [66] investigated metal-Schiff base complexes derived from morpholine (specifically, 2-hydroxyacetophenone with 4-(2-aminoethyl) morpholine) on MCF7 cells over 24 and 48 hours, revealing a decrease in cell proliferation and survival.

In 2013, Zuo et al. [36] examined the effect of Schiff amino acid bases containing copper metal on MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and prostate (PC-3) cancer cells, indicating that these amino acid Schiff bases can reduce cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in cancer cells.

The observed effects at concentrations ranging from 200 to 500µM suggest a dose-dependent relationship, indicating the efficacy of these compounds in targeting cancer cells. This research highlights the promising role of Schiff base compounds as adjunctive anti-cancer agents and their potential for incorporation into novel cancer treatment strategies.

The ability of Schiff base compounds to reduce the proliferation rate of cancer cells and increase mortality compared to control groups underscores their therapeutic potential. These compounds exhibit cytotoxic effects on cancer cells, providing a mechanism for suppressing tumor growth and promoting cell death. The results suggest that Schiff base compounds may have specific molecular targets within cancer cells, making them valuable candidates for further investigation and development in cancer therapy.

It can be concluded that Schiff-base compounds can serve as valuable additions to existing anti-cancer treatments. Their demonstrated ability to impede cancer cell proliferation and induce cell death at multiple concentrations signifies their versatility and potency in combating cancer. By incorporating these compounds into treatment regimens, healthcare providers may enhance the efficacy of current therapies and potentially overcome drug resistance in cancer patients.

The research outcomes provide a solid foundation for exploring the clinical applications of Schiff-base compounds in cancer treatment. Health policymakers should consider integrating these compounds into oncology protocols to improve patient outcomes and broaden the therapeutic options available. Collaborative efforts among researchers, clinicians, and policymakers are essential to facilitate the translation of these findings into practical interventions that can benefit cancer patients worldwide.

In light of these compelling results, health policymakers must prioritize the evaluation and potential implementation of Schiff-base compounds in cancer care. By investing in further research, clinical trials, and regulatory assessments, policymakers can expedite the approval and accessibility of these compounds for cancer patients. Embracing innovation in cancer treatment through the utilization of Schiff base compounds represents a proactive approach to advancing oncology practices and addressing the evolving challenges posed by cancer.

In conclusion, the findings on the anti-cancer properties of Schiff base compounds underscore their significance as promising therapeutic agents in oncology. Health policymakers are encouraged to support the development and integration of these compounds into cancer treatment protocols to enhance patient care and foster advancements in the field of oncology. By harnessing the potential of Schiff base compounds, healthcare systems can strive toward more effective, personalized, and comprehensive cancer management strategies.

Conclusion

Schiff base compounds inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells and induce apoptosis at multiple concentrations, demonstrating their versatility and efficacy in combating cancer.

Acknowledgments: The authors appreciate the manager and staff of the Faculty of Biology for their collaboration in this research.

Ethical Permissions: This article was approved by the Faculty of Biology, Damghan University, Iran (IR.DU.REC.1400.009).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Wennas ON (First Author), Methodologist (25%); Haji Ghasem Kashani M (Second Author), Main Researcher (30%); Abiri E (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (25%); Altememy D (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was done with the financial support of the Faculty of Biology, Damghan University.

Keywords:

HepG2 Cells [MeSH], Adipose Tissue Stem Cells (ASC) [MeSH], Schiff Base [MeSH], Apoptosis [MeSH], Cancer [MeSH], Stem Cells [MeSH], Rat [MeSH]

References

1. Hashemi M, Sabouni E, Rahmanian P, Entezari M, Mojtabavi M, Raei B, et al. Deciphering STAT3 signaling potential in hepatocellular carcinoma: Tumorigenesis, treatment resistance, and pharmacological significance. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023;28(1):33. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s11658-023-00438-9]

2. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108. [Link] [DOI:10.3322/caac.21262]

3. Hashemi M, Abbaszadeh S, Rashidi M, Amini N, Anaraki KT, Motahhary M, et al. STAT3 as a newly emerging target in colorectal cancer therapy: Tumorigenesis, therapy response, and pharmacological/nanoplatform strategies. Environ Res. 2023;233:116458. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2023.116458]

4. Sadrkhanloo M, Paskeh MDA, Hashemi M, Raesi R, Motahhary M, Saghari S, et al. STAT3 signaling in prostate cancer progression and therapy resistance: An oncogenic pathway with diverse functions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114168. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114168]

5. Hashemi M, Esbati N, Rashidi M, Gholami S, Raesi R, Bidoki SS, et al. Biological landscape and nanostructural view in development and reversal of oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. Transl Oncol. 2024;40:101846. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101846]

6. Steck SE, Murphy EA. Dietary patterns and cancer risk. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(2):125-38. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/s41568-019-0227-4]

7. Clifford GM, Georges D, Shiels MS, Engels EA, Albuquerque A, Poynten IM, et al. A meta‐analysis of anal cancer incidence by risk group: Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(1):38-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/ijc.33185]

8. Hashemi M, Nazdari N, Gholamiyan G, Paskeh MDA, Jafari AM, Khodaei E, et al. EZH2 as a potential therapeutic target for gastrointestinal cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;253:154988. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.prp.2023.154988]

9. Yarhusseini A, Sharifzadeh L, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Sayehmiri F, Sayehmiri K. Survival rate of esophageal carcinoma in Iran-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2014;7(2):61-5. [Link]

10. Hashemi M, Daneii P, Zandieh MA, Raesi R, Zahmatkesh N, Bayat M, et al. Non-coding RNA-Mediated N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) deposition: A pivotal regulator of cancer, impacting key signaling pathways in carcinogenesis and therapy response. Noncoding RNA Res. 2023;9(1):84-104. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ncrna.2023.11.005]

11. Chhaniwal N, Li C, Wang J, Qiang G, Qi T, Maher H. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Review of current treatment with a focus on transarterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation. Open J Radiol. 2015;5(1):50-8. [Link] [DOI:10.4236/ojrad.2015.51009]

12. Sell S, Leffert HL. Liver cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(17):2800-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5945]

13. Chuang SC, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P. Liver cancer: Descriptive epidemiology and risk factors other than HBV and HCV infection. Cancer Lett. 2009;286(1):9-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.10.040]

14. Rafati A, Ghaleh HEG, Azarabadi A, Masoudi MR, Afrasiab E, Alvanegh AG. Stem cells as an ideal carrier for gene therapy: A new approach to the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Transpl Immunol. 2022;75:101721. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.trim.2022.101721]

15. Sadrkhanloo M, Paskeh MDA, Hashemi M, Raesi R, Bahonar A, Nakhaee Z, et al. New emerging targets in osteosarcoma therapy: PTEN and PI3K/Akt crosstalk in carcinogenesis. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;251:154902. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.prp.2023.154902]

16. Huang GJ, Gronthos S, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: Their biology and role in regenerative medicine. J Dent Res. 2009;88(9):792-806. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0022034509340867]

17. Raesi R, Zabolian A, Hasani Sadi F, Javanshir S, Salimimoghadam S, Jung YY, et al. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) in cancer metastasis: Molecular interactions and possible therapeutic targets. In: Non-coding RNA transcripts in cancer therapy: Pre-clinical and clinical implications. Hackensack: World Scientific; 2023. p. 247-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1142/9789811267390_0010]

18. Sheng G. The developmental basis of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs). BMC Dev Biol. 2015;15:44. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12861-015-0094-5]

19. Ullah I, Subbarao RB, Rho GJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells-current trends and future prospective. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(2):e00191. [Link] [DOI:10.1042/BSR20150025]

20. Lee JH, Park CH, Chun KH, Hong SS. Effect of adipose-derived stem cell-conditioned medium on the proliferation and migration of B16 melanoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(2):730-6. [Link] [DOI:10.3892/ol.2015.3360]

21. Bobis S, Jarocha D, Majka M. Mesenchymal stem cells: Characteristics and clinical applications. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2006;44(4):215-30. [Link]