Received: 2025/02/19 | Accepted: 2025/05/22 | Published: 2025/07/8

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1557-en.html

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Therapeutic communication is integral to professional nursing practice and a key indicator of quality patient care in any setting, including the critical care environment. There are important differences between therapeutic communication and everyday or social communication, as therapeutic communication is meaningful, purposeful, and goal-oriented. It serves to provide emotional support to patients on emotional, psychological, and moral levels while simultaneously empowering them to make informed clinical decisions. Critically ill, sedated, paralyzed, intubated, or otherwise noncommunicative patients are a common population with which critical care nurses engage in the acute/critical care setting. Thus, in these contexts, a nurse’s level of therapeutic communication is integral to dignity, safety, and holistic care [1].

Objectives: Critical care is a challenging environment where a critically ill patient’s life may depend on the decisions or life-saving treatments administered within a matter of minutes. Nurses in such areas must make quick clinical decisions, and these decisions should simultaneously encompass compassionate and ethical care for patients and their relatives. The inherent tension of critical care practice may lead to negative impacts on the quality of communications, which can result in misunderstandings, ethical tensions, and even the erosion of patient-focused care [2]. Therefore, it is crucial to enhance the knowledge and skills of nurses in therapeutic communication to improve nursing care and outcomes for patients.

Ethical nursing care is grounded in ethical principles, and these principles guide nurses’ conduct, serving as the foundation that nurses rely upon in clinical practice when discussing patient care. Autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, confidentiality, and maintaining human dignity are some of the significant ethical principles within healthcare. Ethical quandaries, such as end-of-life issues, informed consent, withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining treatment, and the distribution of scarce healthcare resources, are more likely to be confronted in the critical care unit. Nurses often act as the patient’s advocate and link between the patient, family, and healthcare team, which makes them pivotal in the ethical decision-making process [3].

Therapeutic communication is the ethical practice of nursing in action. Nurses with effective communication skills can explain complex medical information in a clear and concise manner, facilitate patient autonomy, and navigate emotionally charged discussions related to prognosis, treatment options, and end-of-life care. Humanized communication builds trust between both parties, decreases patient and family stress, including psychosocial issues, and enhances shared decision-making [4], which is a critical requirement in the care milieu, as patients in this setting are known to be highly vulnerable and disempowered.

It has been shown that poor communication and low ethical consciousness in nurses may result in moral distress, dissatisfaction, and potential jeopardy to patients. Moral distress occurs when nurses know the right thing to do ethically but cannot take that action because of institutional constraints, lack of support, or insufficient information. Research demonstrates that specialized ethics education and communication training may substantially mitigate moral distress and empower nurses in ethically challenging situations [5, 6].

Educative actions are pivotal for enhancing nurses’ skills in ethical decision-making and therapeutic communication. There have been structured educational programs that incorporate ethics and communication, which increase nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. In the work of Radtke et al. [7], ethics-based communication training was reported to significantly enhance intensive care nurses’ ethical decision-making and the quality of communication between nurses and patients. In a similar vein, Younis et al. [8] reported that the compassionate communication training-acquired skills of a group of nurses were significantly better than those of a control group, expressing more empathy in conversations with patients and providing clearer explanations, as well as demonstrating good professional behavior.

In critical care, the nurse-patient relationship is typically short and intense, with nurses needing to rapidly gain patients’ trust and establish rapport. In fact, therapeutic communication includes such aspects as active listening, empathy, appropriate use of silence, validation of feelings, and respectful non-verbal communication, all of which are considered important for cultivating successful nurse-patient interactions. These skills are especially crucial for patients who are fearful, in pain, or uncertain about the future of their health [9].

Maintaining professional boundaries is another ethical dilemma with which critical care nurses frequently grapple. Emotional engagement, extended contact with critically ill patients, and intimate dealings with family members can obscure professional boundaries unless ethical guidance is provided. Moreover, ethical communication at these boundaries can provide positive guidance and establish the best path for patients.

Although the importance of ethical and therapeutic communication has been established, some studies suggest that critical care nurses do not receive formal education in these areas. Communication skills are thought to be acquired naturally over time through experience in clinical practice, but there is evidence that education with a predetermined structure is needed for communication among healthcare providers to be uniform and effective. The application of ethical principles to communication training allows nurses to be trained in a comprehensive process that can be considered a framework for navigating the complex relationships and extraordinary situations encountered in everyday work [10].

In the context of the Iraqi healthcare system, critical care nurses are additionally subjected to even greater pressures due to a large patient population, fewer supplies, and high work-related stressors. If these needs are unmet, the impact on quality communication and ethical practice could be further impeded. An urgency for locally based, evidence-informed educational strategies to empower nurses to care for patients in ways that are ethical and patient-centered is evolving [11].

This study aimed to assess critical care unit nurses’ knowledge related to the concepts of ethical and therapeutic communication, as well as the effectiveness of an integrated educational program on critical care unit nurses’ knowledge.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sample

This quantitative quasi-experimental study was carried out using the test-retest method with a pre-test and post-test for both the experimental and control groups of critical care unit nurses from March 20, 2025, to July 10, 2025, at Hilla Teaching Hospitals in Babylon city. The sample size was calculated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4), assuming a medium effect size (d=0.5), a significance level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 80%. The minimum required sample was 102 participants, which was increased to 110 to account for possible dropouts.

Non-probability purposive sampling was done to select nurses working in critical care units at teaching hospitals. The sample consisted of 110 nurses, divided into two groups: 55 nurses constituted the experimental group, and 55 nurses constituted the control group. The educational program was introduced to the experimental group, while the control group was not exposed to it. Random allocation of the sample was performed to avoid selection bias and to control for potential confounding factors.

Inclusion criteria included nurses working in critical care units in Hilla teaching hospitals with at least one year of experience, regardless of gender, educational level, or age, who provided consent to participate in the study.

Instrument

A constructed questionnaire was prepared and modified after a thorough review of the relevant literature. This questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part included demographic data, such as age, gender, educational level, marital status, and years of experience. The second part covered employment data, including years of experience, years of experience in the ICU, and special training. The third part addressed nurses’ knowledge related to ethical and therapeutic communication concepts, which comprised 72 items. The reliability of the test-retest was assessed using a correlation coefficient of 0.84.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted from April 20 to July 10, 2025. All participants first received an explanation of the study’s objectives and signed informed consent, which included the right to withdraw at any time. A pre-test was administered to both groups to assess baseline knowledge of ethical and therapeutic communication. The experimental group then attended an educational program held in a dedicated hall. Immediately after the session, both groups completed post-test to measure improvement, followed by follow-up one month later to assess knowledge retention and practice stability. Questionnaires were distributed in hospitals, briefly explained, and returned in sealed envelopes to ensure anonymity; only the researcher had access to the responses.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 utilizing inferential statistics, including independent t-tests, paired t-tests, and chi-square tests. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Findings

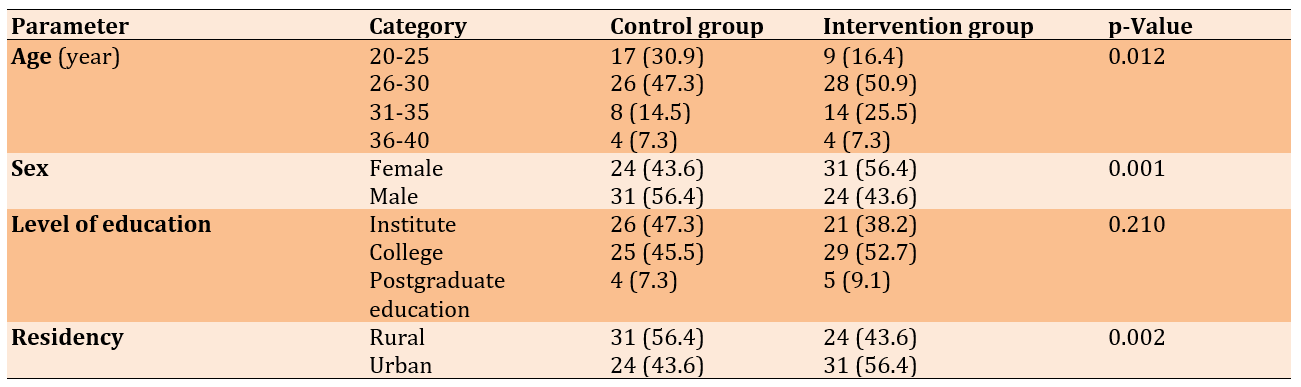

A total of 110 nurses participated in the research. The majority of participants were aged 26-30, with 47.3% in this group for the first category and 50.9% in the second category. The distribution of sex among participants showed a slight male predominance, with 56.4% of males in the first category compared to 43.6% females. Nearly half have an institute-level education, with 47.3% in the first category and 38.2% in the second. The residency status indicated a higher representation of rural participants, with 56.4% from rural areas in the first category and 43.6% from urban areas (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of participants

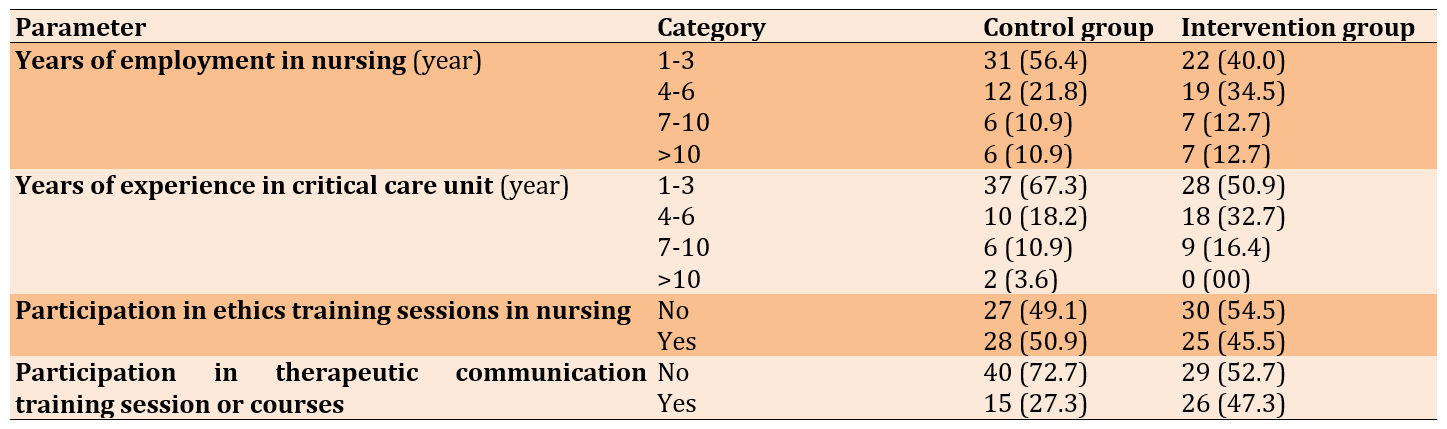

The control group had a higher proportion of nurses with 1-3 years of employment at 56.4%, while the intervention group showed a significant number with 4-6 years of experience at 34.5% (Table 2)

Table 2. Frequency of employment characteristics of participants

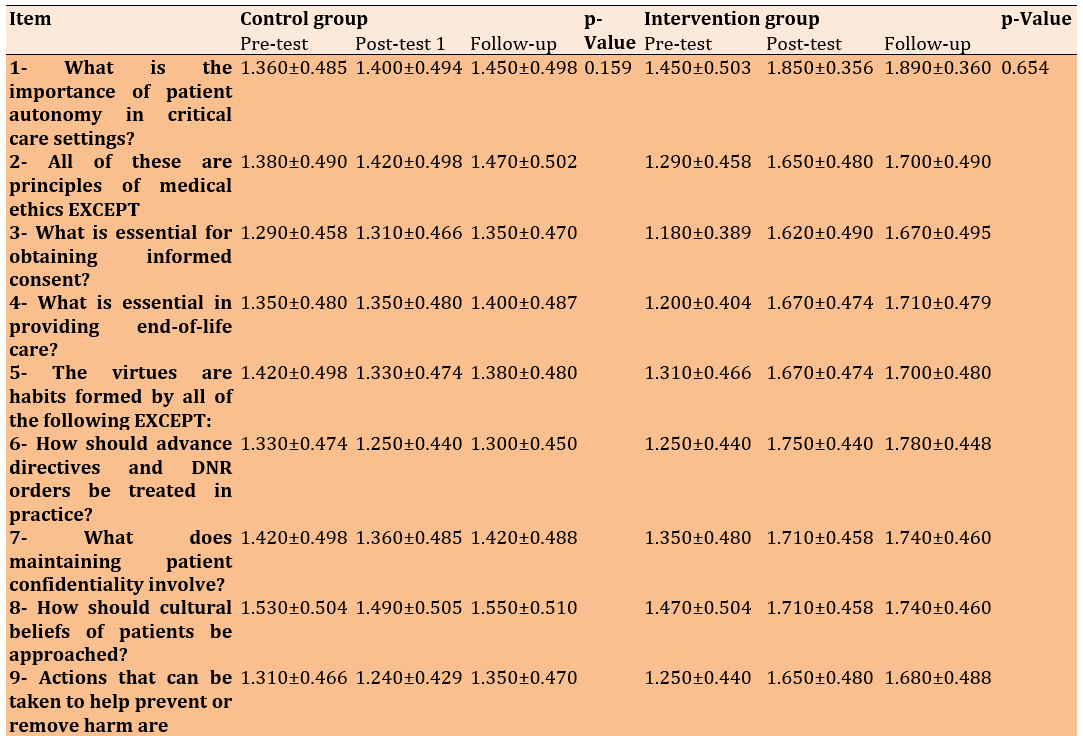

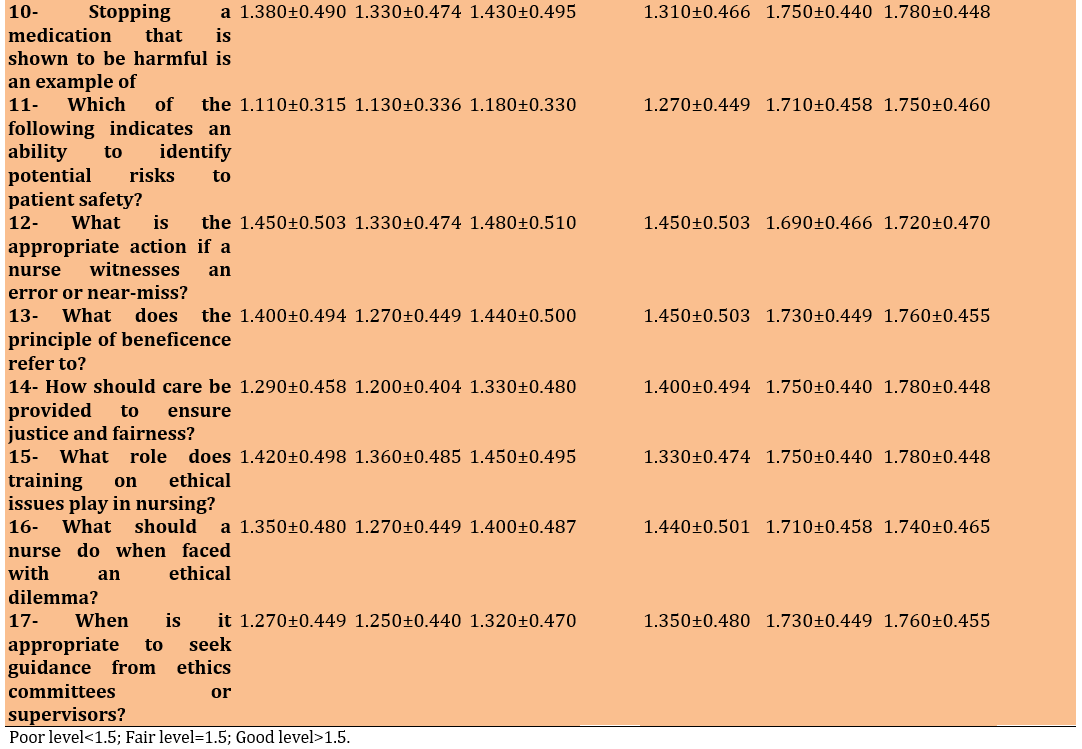

There was a notable improvement in the knowledge of ethical principles among the intervention group, while the control group demonstrated minimal or no meaningful improvement across most items. Substantial improvements were also observed in questions related to informed consent, end-of-life care, and advance directives, with post-test mean scores in the intervention group consistently approaching or exceeding 1.70, reflecting a “good” level of knowledge. The intervention group’s score on understanding the principle of beneficence improved from 1.450±0.503 to 1.730±0.449, while the control group showed a slight decrease from 1.400±0.494 to 1.270±0.449. The intervention group demonstrated consistently higher post-test means in all 17 items, with many scores nearing the upper “good knowledge” range (≥1.5). In contrast, the control group’s improvements were inconsistent and modest, with most post-test scores remaining within the “fair” or “poor” range (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of mean nurses’ knowledge regarding ethical principles in the critical care units

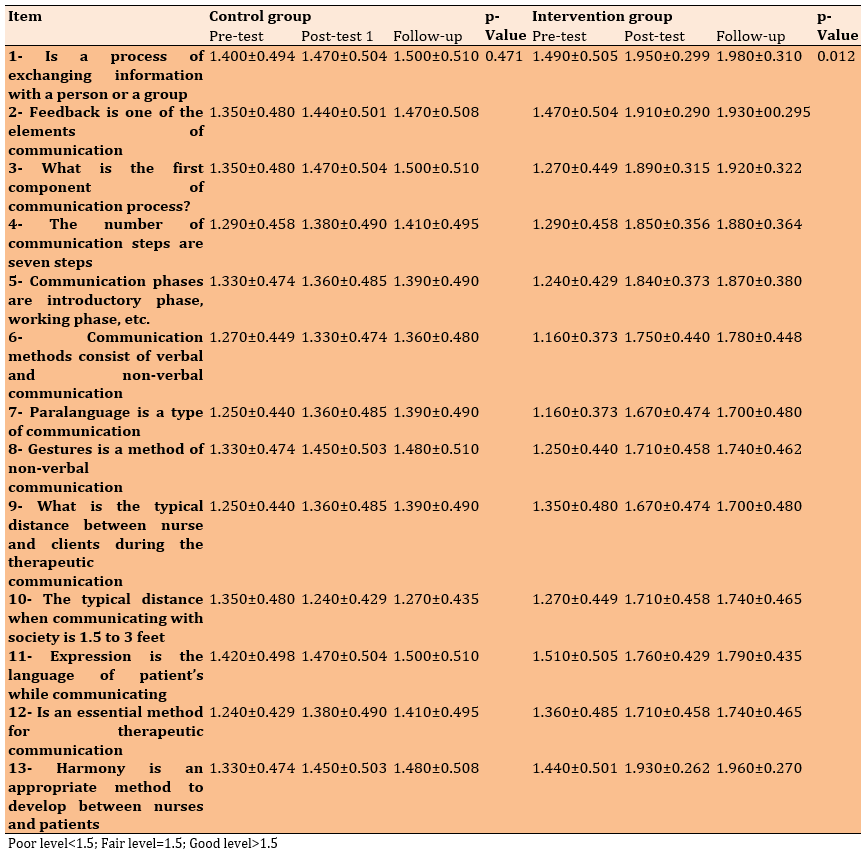

There was a significant improvement in the intervention group across all assessed items regarding communication after the intervention. For example, item 1 showed a marked increase in the mean score from 1.490±0.505 to 1.950±0.299 (p=0.012), indicating a movement from a fair level of knowledge to a good level. In contrast, the control group showed minimal or no improvement (from 1.400±0.494 to 1.470±0.504; p=0.471), highlighting the program’s impact.

The program appeared particularly effective in improving knowledge about core communication concepts, such as feedback (item 2), the components and phases of communication (items 3-5), and types of communication, including verbal, non-verbal, and paralanguage (items 6-8). Post-intervention mean scores in the intervention group for these items approached the good level (≥1.5), whereas the control group largely remained at the fair or poor levels. The item on harmony as a tool to build therapeutic relationships (item 13) showed one of the most significant improvements in the intervention group (from 1.440±0.501 to 1.930±0.262), reinforcing the ethical dimension of the program in nurturing empathy and rapport (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of nurses’ mean knowledge about communication in the critical care units

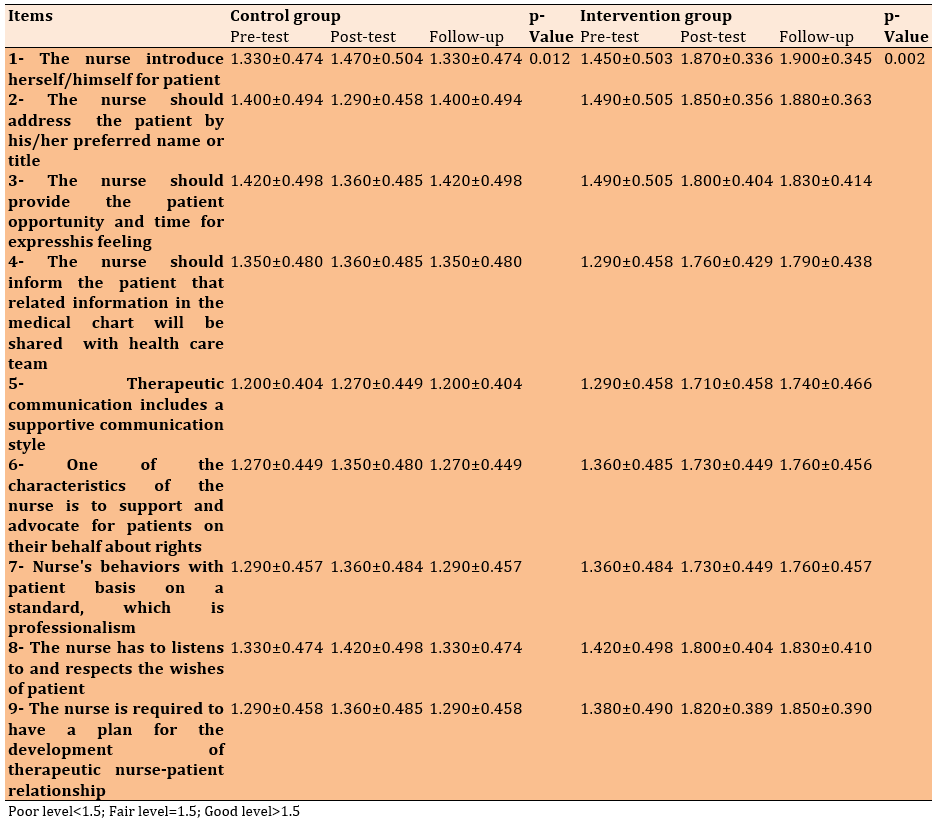

The post-test results of the intervention group demonstrated notable improvements regarding nurse-patient relationship, with most item means falling below the fair level threshold, indicating a shift from poor to fair and good practice levels. Specifically, statistically significant improvements were observed in the intervention group for key behaviors, such as introducing oneself to patients (p=0.002), using the patient’s preferred name (mean=1.850±0.356 post-test vs. 1.490±0.505 pre-test), and providing opportunities for patients to express their feelings (mean=1.800±0.404 post-test vs. 1.490±0.505 pre-test). In contrast, the control group showed only minor, statistically insignificant changes, suggesting that the improvement in the intervention group can be attributed to the integrated communication and ethics program (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of experimental and control group nurses’ responses regarding nurse-patient relationship

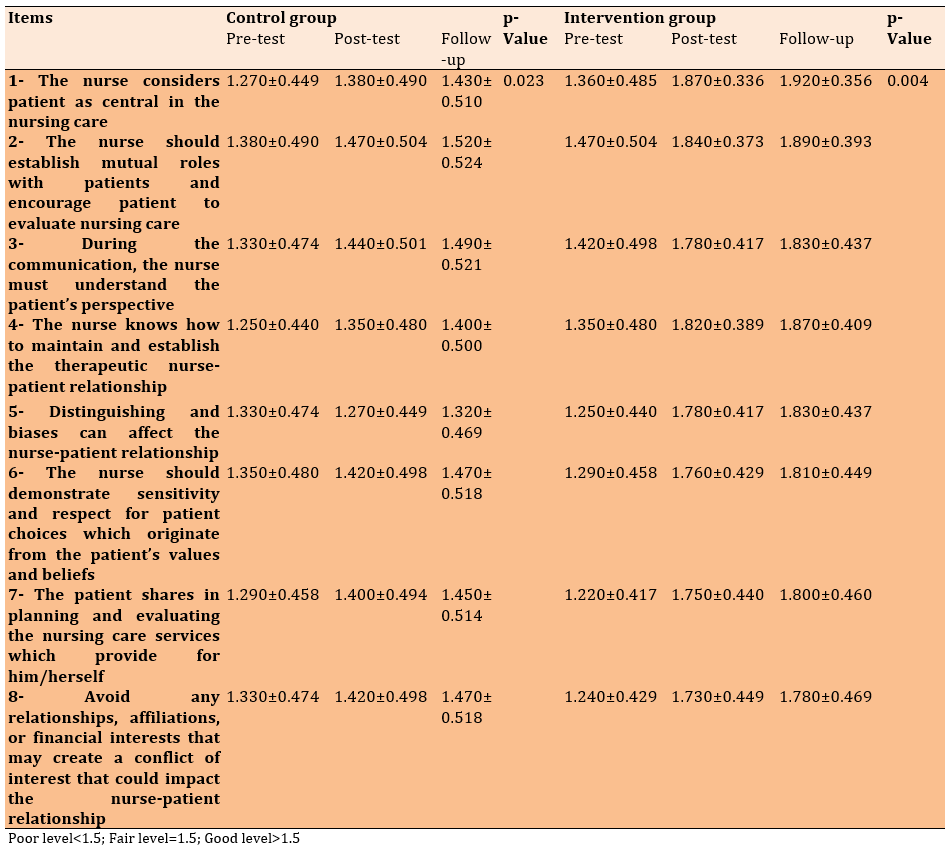

There was a statistically significant improvement in the therapeutic communication practices of nurses in the intervention group after the program. Specifically, the intervention group showed clear gains across all items, with post-test means notably lower than 1.5, indicating a shift toward a good level of patient-centered communication. In contrast, the control group demonstrated only minor, statistically less robust improvements, remaining within the fair to poor range on most items (Table 6)

Table 6. Comparison of nurses mean patient-centered nursing care through therapeutic communication

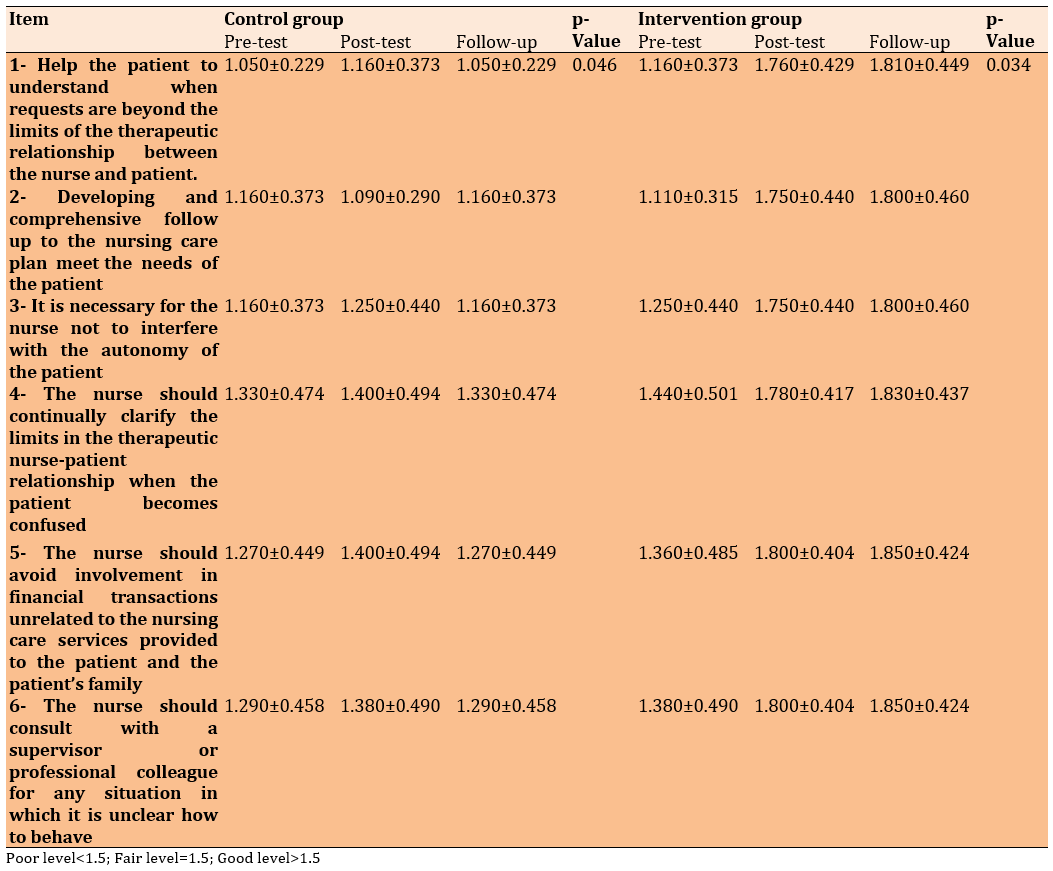

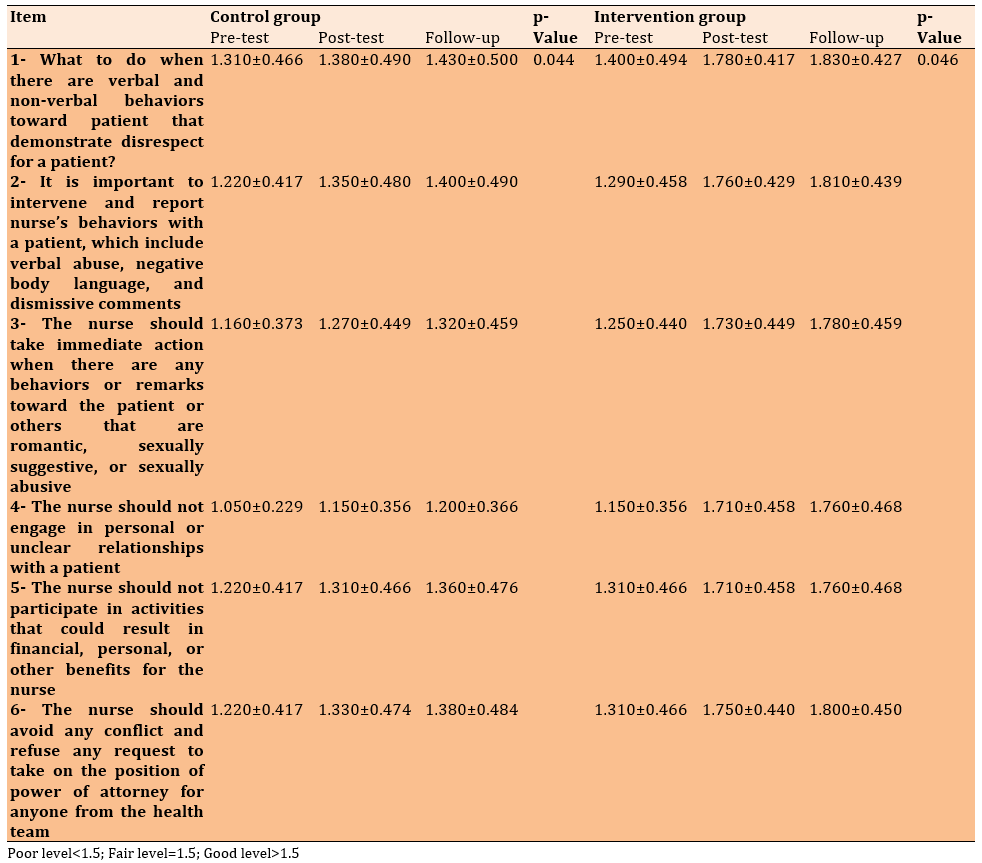

There was a statistically significant improvement in the post-test responses of the intervention group regarding various components of maintaining therapeutic boundaries in nurse-patient relationships. Notably, in the intervention group, the mean scores post-intervention improved across all items, transitioning from a poor or fair level to borderline or better levels of therapeutic communication practices. For instance, on Item 1, which addresses nurses’ ability to help patients when requests exceed the boundaries of the therapeutic relationship, the intervention group’s mean score improved from 1.16 (pre-test) to 1.76 (post-test), with a statistically significant p-value of 0.034. In contrast, the control group showed only minor and less impactful improvement (p=0.046), suggesting the effectiveness of the educational intervention implemented with the intervention group (Table 7).

Table 7. Comparison of nurses’ mean scores regarding maintaining boundaries by communication

The intervention group demonstrated statistically significant improvements across all six items regarding nurses’ ability to protect patients from harm within the scope of therapeutic communication following the intervention, with mean scores increasing from poor or fair levels to consistently fair levels (e.g., Item 1 improved from 1.400 to 1.780, p=0.046). In contrast, the control group also showed minor improvements, but their gains were more modest (e.g., Item 1 improved from 1.310 to 1.380, p=0.044), suggesting that the intervention had a stronger effect on the intervention group. There was also a significant growth in acknowledging the importance of intervening in disrespectful or exploitative situations (Items 1 and 2; Table 8).

Table 8. Comparison of nurses’ mean scores regarding patient protection from harm during therapeutic communication

Discussion

The notable improvement in the knowledge of intervention group aligns with findings by Beauchamp and Childress [3], highlighting autonomy as a core ethical principle requiring active reinforcement in high-pressure environments, like critical care units. The good level of knowledge in the intervention group aligns with the study by Helmers et al. [4], who stressed that structured ethics education significantly enhances nurses’ preparedness in addressing complex end-of-life decisions and respecting patients’ wishes. The improvement in the intervention group’s score on understanding the principle of beneficence further supports evidence from Grace [5], who emphasized that consistent ethics and communication training enhance nurses’ ability to act in patients’ best interests while reducing moral distress. Knowledge related to confidentiality, cultural beliefs, and identifying risks to patient safety also improved significantly more in the intervention group, consistent with Haddad and Geiger [6], who assert that ethical knowledge correlates strongly with culturally competent and legally sound nursing practices. The intervention group demonstrated consistently higher post-test means in all 17 items. This finding is echoed in the study by Radtke et al. [7], reporting that an integrated approach to ethical and communication training results in measurable improvements in ethical decision-making and nurse-patient communication in ICU settings. Furthermore, Aiken et al. [12] concluded that improved ethical knowledge significantly contributes to higher patient safety, reduced ethical conflicts, and enhanced job satisfaction among ICU nurses.

The intervention group demonstrated a significant improvement in knowledge across all assessed items following the program, moving from a fair to a good level of understanding. This enhancement was particularly evident in core communication concepts, where participants showed substantial gains in their knowledge of feedback and various communication types. These results are consistent with recent research emphasizing the value of communication training in critical care settings. Shimran and Ali [13] found that an integrated program combining ethics and therapeutic communication leads to higher levels of patient satisfaction and nurse confidence, especially in high-stress environments, like intensive care and hemodialysis units. Furthermore, a study by Younis et al. [8] stressed that without targeted interventions, nurses often lack structured knowledge about therapeutic communication models and struggle to apply ethical principles in complex clinical conversations.

The intervention group exhibited significant improvements in nurse-patient relationships, with most behaviors shifting from poor to fair or good practice levels. These results are consistent with findings by Slatore et al. [9], who highlighted that structured communication training significantly improves nurses’ ability to engage in empathetic, respectful, and professional interactions in high-stress environments like critical care. The observed improvement in the nurses’ ability to advocate for patients’ rights and maintain ethical standards post-intervention aligns with the work of Water et al. [14], who emphasized that ethical training programs are essential for developing advocacy competencies and moral sensitivity in nursing care. There were gains in more abstract components of therapeutic communication, such as planning therapeutic interactions, which supports the view that communication is not merely a spontaneous interaction but requires ethical foresight and clinical preparation. According to Dehghani et al. [10], when nurses are educated in ethical reasoning alongside communication strategies, their confidence and clarity in planning and executing patient-centered dialogue markedly increase. Furthermore, the improved scores for nurse behaviors based on professional standards indicated enhanced ethical awareness, which resonates with the findings of Jamshidian et al. [11], who found that educational programs integrating ethics into communication training significantly improve nurses’ ethical decision-making and interpersonal behaviors.

The educational programs was effective in enhancing therapeutic communication, particularly in critical care settings where such skills are essential. In alignment with this study, Slatore et al. [9] found that critical care nurses who receive comprehensive training in ethical and communication principles exhibit significantly higher scores in empathy, respect for patient autonomy, and shared decision-making practices. They emphasize that training interventions rooted in real clinical scenarios and ethical dilemmas are particularly effective in fostering long-lasting behavioral change.

The significant progress in the intervention group—especially in areas, such as respecting patient autonomy, shared decision-making, and minimizing bias—corresponds with findings by Zare et al. [15], who argue that therapeutic communication in ICU settings leads not only to better nurse-patient relationships but also to improved clinical outcomes. They highlight that nurse training should integrate ethical reasoning with emotional intelligence and communication theory to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice. Furthermore, the notable improvements observed in how nurses approach patient individuality and boundaries reflect the outcomes of a study by Eun et al. [16], which found that communication programs incorporating ethical content are significantly more effective in teaching nurses how to avoid conflicts of interest, respect cultural differences, and protect patient dignity. Their research confirm that combining therapeutic communication with ethical frameworks leads to improved holistic care and patient satisfaction.

A significant improvement was observed in the post-test responses of the intervention group regarding various components of maintaining therapeutic boundaries in nurse-patient relationships. These results support the growing body of evidence indicating that integrated ethical and therapeutic communication training programs significantly enhance nurses’ understanding and application of professional boundaries, especially in critical care contexts where emotional intensity and ethical complexity are high. Taşkıran et al. [17] showed that a structured ethics and communication program can improve ICU nurses’ ability to manage professional relationships, reduce emotional over-involvement, and increase adherence to ethical practice standards. They report that clarity in nurse-patient boundaries leads to better patient outcomes and reduced moral distress among nurses. Moreover, the marked improvement in items, such as avoiding involvement in financial transactions and consulting supervisors in unclear ethical situations reflects a growing ethical maturity and professional prudence among nurses following the intervention. Alzahrani et al. [18] concluded that combining ethical training with communication strategies leads to a more nuanced understanding of professional boundaries and improves clinical conduct among nurses in high-stakes environments.

The improvements regarding nurses’ ability to protect patients from harm within the scope of therapeutic communication underscore the impact of integrating ethical training with therapeutic communication skills in critical care settings. Similar findings have been reported in recent studies. For example, Alzahrani et al. [18] emphasize that ethically grounded communication training leads to significant improvements in nurses’ ability to intervene appropriately in situations involving disrespect or violations of professional boundaries. They conclude that communication infused with ethical awareness enhances nurses’ readiness to respond to verbal, non-verbal, and behavioral cues that may harm patients’ dignity. Furthermore, Park et al. [19] found that integrated training programs significantly improve nurses’ reporting behaviors and ethical decision-making, particularly when encountering inappropriate sexual remarks, romantic advances, or financial exploitation. Additionally, Karami et al. [20] conclude that programs combining therapeutic communication and ethical principles fosters nurses’ assertiveness in refusing roles, such as power of attorney, thus maintaining professional boundaries—a key aspect reflected in Item 6 of this study. The intervention group’s mean improvement indicated increased confidence in managing such ethical dilemmas. A significant growth was found in acknowledging the importance of intervening in disrespectful or exploitative situations (Items 1 and 2). This supports the findings of Albagawi and Jones [21], who highlighted the need for continual ethical training in critical care settings, where emotional boundaries are frequently tested.

An integrated educational program was highly effective in improving critical care nurses’ knowledge of ethical principles and therapeutic communication. The nurses in the intervention group showed significant improvement, with their scores moving from “poor” to “good,” while the control group saw minimal change. This improvement was most notable in ethical decision-making, communication skills, and patient safety. Interestingly, age was the only demographic factor that significantly influenced knowledge gains, and a nurse’s education level was strongly linked to their practical skills after the training. Factors, such as sex and years of experience did not have a significant impact on the results, suggesting that the program’s effectiveness was widespread across the nursing staff.

We recommend that this program be implemented as a standard part of in-service training for critical care units. To maximize its impact, training modules should be tailored to different age groups and educational backgrounds. It is also clear that encouraging participation in ethics training is beneficial, as it significantly boosts nurses’ practical application of these skills. We also suggest ongoing monitoring through pre- and post-assessments to ensure that the training remains relevant and effective. Finally, future studies should be conducted to evaluate the long-term effects of this program on both nursing practice and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The integrated ethical and therapeutic communication educational program is effective in enhancing critical care nurses’ knowledge and practices.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their appreciation to Hilla Teaching Hospitals and the participating nurses for their cooperation and support during data collection.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical approval was obtained from the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the College of Nursing, University of Babylon, and from the administration of Hilla Teaching Hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Shimran HY (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (60%); Adham Ali S (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.