Volume 16, Issue 4 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(4): 375-380 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: 893.3/066/438.5.2.1.1/2023

History

Received: 2024/11/1 | Accepted: 2024/12/3 | Published: 2024/12/15

Received: 2024/11/1 | Accepted: 2024/12/3 | Published: 2024/12/15

How to cite this article

Riu S, Nursalam N, Nusi T, Yahya I, Rahil N, Taplo Y. Effect of Emergency Nurses’ Work Stress, Workload, and Motivation on Emergency Severity Index Implementation. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (4) :375-380

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1541-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1541-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Advanced Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Science, Muhammadiyah University Manado, Manado, Indonesia

3- Department of Nursing, College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

4- Department of Nursing, College of Medical, Veterinary, and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Science, Muhammadiyah University Manado, Manado, Indonesia

3- Department of Nursing, College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

4- Department of Nursing, College of Medical, Veterinary, and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland

Full-Text (HTML) (620 Views)

Introduction

The emergency room (ER) is a lifesaving hospital unit for patients who need immediate medical attention. Trauma-related incidents, including traffic accidents, violence, falls, and poisoning, account for more than 5 million deaths worldwide each year, making the ER a key entry point for life-saving interventions and preventing disabilities in affected individuals [1]. The quality of care in the ER significantly impacts patient outcomes, with one key indicator being the effectiveness of triage implementation. Triage is the process of assessing and prioritizing patients based on the severity of their conditions to ensure timely and appropriate treatment. Triage of patients based on the severity system is critical, especially during surges of patient admissions, to lower mortality and morbidity rates. Despite its necessity, triage errors can result in treatment delays, lifelong disabilities, or death, highlighting the essential nature of triage performed well [2, 3].

The emergency severity index (ESI) is one of several triage systems used internationally, and it has been adopted in part due to its precise, structured methodology for stratifying patients into five categories based on the anticipated urgency and resource needs. The ESI identifies patients who need immediate life-saving interventions and considers the resources required to treat their conditions [4]. This approach helps achieve better patient flow and facilitates better resource usage, hence a reproducible standard approach to maximize ER productivity and quality of patient care.

While ESI has benefits, it is not easy to carry out, and it is affected by various factors such as work stress, workload, and motivation of ER nurses. They are at the heart of triage, executing rapid assessments and ensuring patients are prioritized. Yet, worldwide, studies show the accuracy of triage decisions is far from optimal, with up to 56.2% of triage decisions accurate in Taiwan, 59.2% in Brazil, and 58.7% in Pennsylvania [2]. The impact of triage can affect patient outcomes, and the factors contributing to those decisions need to be addressed to improve nurse performance.

Due to emergency care's dynamic and high-stakes nature, ER nurses can face significant work stress. Recurrent exposure to high-risk environments and potentially deadly circumstances may result in psychosocial stress, causing alterations in decisions, faculties, and performance in general [5, 6]. The workload is another key factor; ERs often have high patient density and limited staffing. Overworked nurses may suffer from cognitive fatigue, making them more prone to mistakes [7, 8]. In contrast, motivation, which intrinsic and extrinsic factors can influence, plays a significant role in achieving focus, resilience, and job satisfaction among nurses [9]. Knowing how these elements interact with triage implementation will help make ER operations better.

Existing literature has examined the impact of work stress, workload, and motivation on the performance of nurses in different environments. For instance, Lu et al. emphasized that excessive workload threatens patient safety and staff well-being [9]. At the same time, Toulson et al. highlighted the significance of allocating resources during the triage process [10]. However, research on these factors concerning the implementation of ESI in Indonesia is limited. There is a need for more investigation of the gap to develop strategies to improve triaging better and faster in the ERs.

This research studies the factors correlated with implementing the ESI triage system, with special attention to work stress, workload, and motivation. Findings will help inform hospital administrators and policymakers on targeted interventions by identifying significant influences on triage performance. Key areas that can be addressed include improving nurse performance and reducing errors, which ultimately have the potential to improve patient outcomes in emergency care settings. Implementing the ESI triage system is vital to maximizing ER operations and patients. Yet it is affected by multiple, interconnected drivers, including stress at work, workload, and motivation.

Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap in the knowledge base by exploring these antecedents in the ESI context to advance the work on enhancing the quality of care in an emergency setting.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Sidoarjo Regional General Hospital, a tertiary-level healthcare facility with a well-established emergency department, in 2023. The study population consisted of all nurses employed in the emergency department for at least six months who had direct involvement in triage decision-making and were familiar with the ESI system. A minimum sample size of 68 participants was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (a medium effect size=0.15, α=0.05, and 1-β=0.8), considering three explanatory variables (work stress, workload, and motivation). The final sample included 72 nurses, exceeding the minimum requirement. However, the availability of emergency nurses within the emergency department limited further expansion of the sample size [11].

Instrument

The study measured four parameters; Work stress, workload, motivation, and ESI implementation.

Work stress: was assessed using a validated questionnaire adapted from Djariah et al. This scale comprised 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater stress levels [12]. This study confirmed the reliability of the questionnaire with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.

Workload: was evaluated using a questionnaire adapted from Wicaksono et al. This instrument included 15 items assessing workload components, such as time pressure, task complexity, and patient-to-nurse ratios. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale [13]. The instrument demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89).

Motivation: was measured using a scale adapted from Indrayanti et al. The 12-item questionnaire assessed intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors, such as job satisfaction, recognition, and professional growth opportunities. Responses were captured on a 5-point Likert scale [14], with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

ESI implementation: was assessed using a researcher-developed questionnaire based on the ESI triage algorithm. The instrument comprised 14 items evaluating nurses’ adherence to ESI protocols and decision-making accuracy. Two experts in emergency nursing and healthcare management tested the initial questionnaire's content validity, achieving a validity score of 70%. After removing five invalid items, the final instrument demonstrated strong reliability with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

Procedure

Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participation was voluntary, and respondents could withdraw at any time without penalty. Data confidentiality was ensured by anonymizing all responses and securely storing the data in a password-protected system accessible only to the research team. Data collection was conducted over four weeks. Participants were recruited through announcements and face-to-face invitations during shift handovers. Data were collected using self-administered questionnaires in a private, quiet area within the hospital to ensure confidentiality and minimize disruptions.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26 software and the relationships between work stress, workload, motivation, and ESI implementation were assessed using multiple linear regression analysis. The regression model included the work stress, workload, and motivation and ESI implementation at p<0.05.

Findings

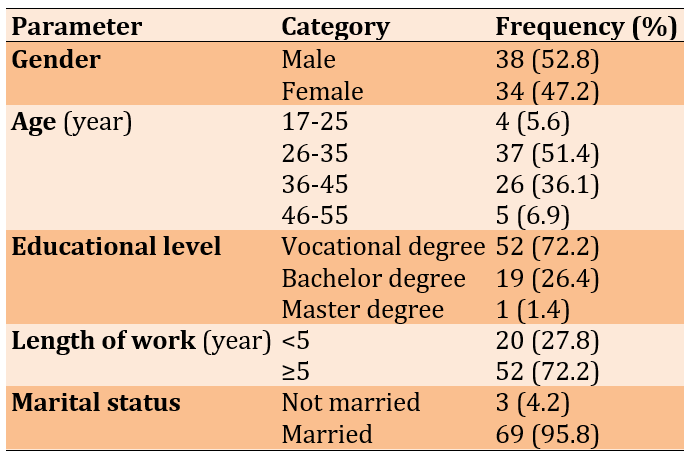

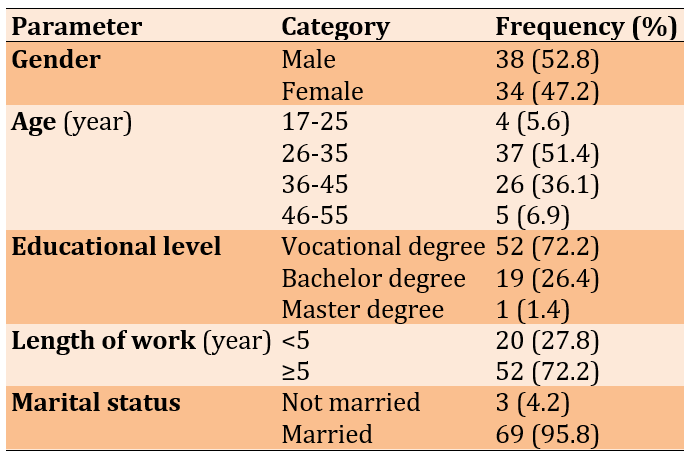

The majority of samples were male (52.8%), between 26 and 35 years old (51.4%), with a vocational degree (72.2%), and married (95.8%; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency distribution of respondents by gender, age, education level, length of work, followed training and marital status

The descriptive analysis revealed moderate levels of work stress (26.63±6.47), workload (119.08±14.13), and motivation (100.10±12.10) among participants, with ESI implementation scores averaging 49.43±5.75.

All three explanatory parameters were positively associated with ESI implementation. Work stress was found to have a significant positive relationship with ESI implementation (B=0.24; t=2.51; p=0.015). Workload emerged as the strongest predictor of ESI implementation (B=0.14; t=3.27; p=0.002). Motivation also showed a significant positive relationship with ESI implementation (B=0.1; t=2.04; p=0.046).

The overall regression model was statistically significant (F=9.63; p<0.001), indicating that the combination of work stress, workload, and motivation explained a substantial portion of the variance in ESI implementation. The adjusted R-squared value of 0.27 suggested that 27% of the variability in ESI implementation can be attributed to these three factors.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between work stress, workload, motivation, and implementing the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) in the emergency room. The findings revealed that all three factors, work stress, workload, and motivation, were positively associated with the implementation of ESI. Among these, workload emerged as the most significant factor, underscoring its pivotal role in determining triage efficiency and accuracy.

The study found that workload was the most significant barrier to ESI implementation. This is consistent with prior evidence showing that overload conditions detrimentally affect cognitive performance, speed, and error probability for triage decisions [15-16]. This job is inherently performed under tremendous pressure and requires rapid and accurate evaluation of the patient's condition despite time constraints. When nurses are overwhelmed, their ability to prioritize effectively is compromised, which could jeopardize patient safety. Managing workloads in ER settings requires more than just lowering nurse-to-patient ratios. These include the right balance of delegation of tasks, the use of technology, including electronic health records and triage assistance systems, and an adequate supply of humans and materials. So, adding decision-support systems could help relieve the cognitive load of triage by supplying real-time data and risk assessments. These systems have demonstrated utility in improving triage accuracy and accurate diagnosis in high-acuity settings [15]. The unstable workload varies with patient acuity, time of day, and unexpected emergencies. So, dynamic resource allocation, like activating surge capacity protocols during peak times, is necessary. Training ER staff to adapt effectively to different workload levels and promoting teamwork could also lessen the adverse effects of a high workload on triage performance.

Work stress significantly affects the implementation of ESI, albeit to a lesser degree than workload. ER nurses often operate in unpredictable environments, life-or-death situations, and high emotional demands. Chronic exposure to such stressors can lead to psychological fatigue, reduced attentiveness, and impaired decision-making [17, 18]. Stress management strategies tailored to the unique challenges of ER work are critical. These could include structured debriefing sessions after critical incidents, access to mental health resources, and regular stress management workshops. Additionally, promoting a supportive workplace culture where nurses feel valued and empowered can buffer the adverse effects of stress. For example, team-based approaches to triage, where decision-making responsibility is shared, can reduce individual stress levels and improve the overall quality of care. Another important consideration is the role of stress in triggering defensive or risk-averse behaviors in triage decisions. Stress may lead nurses to over-triage patients, assigning higher acuity levels to avoid potential adverse outcomes. While this may reduce immediate risks, it can strain ER resources and compromise care for genuinely critical patients. Addressing this requires balancing stress mitigation with enhanced training to boost confidence and decision-making accuracy.

Motivation was found to have a significant positive relationship with ESI implementation. Motivated nurses are more likely to approach triage with focus, diligence, and resilience despite the challenges of ER work [19, 20]. Intrinsic motivation, such as professional pride and commitment to patient care, often drives higher engagement and performance. Extrinsic motivators, including recognition, career advancement opportunities, and financial incentives, further reinforce this effect [21]. Hospital administrators can enhance motivation by creating a culture of recognition and reward [22]. Simple gestures, such as acknowledging exemplary performance in triage, can profoundly impact morale. Providing opportunities for career development, such as advanced training in emergency nursing or leadership roles, can also sustain long-term motivation [23]. Interestingly, motivation interacts with both workload and stress. Highly motivated nurses may better manage heavy workloads and cope with stress, demonstrating resilience and adaptability [24]. This suggests that fostering motivation could indirectly mitigate the negative impacts of workload and stress on triage performance.

The interplay between workload, stress, and motivation highlights the complexity of factors influencing ESI implementation. While high workload and stress often have adverse effects, they can be moderated by strong motivation and a supportive work environment. For instance, a motivated nurse under stress might still perform well if supported by a cohesive team and adequate resources [25]. Conversely, low motivation could exacerbate the adverse effects of workload and stress, leading to suboptimal triage outcomes [26]. This dynamic interplay suggests the need for integrated interventions. Addressing these factors in isolation is unlikely to yield significant improvements. Instead, hospitals should adopt a comprehensive approach, simultaneously managing workload, reducing stress, and fostering motivation [27].

This research has several practical and policy implications. Workload management systems, which may encompass dynamic scheduling and real-time resource monitoring, should be introduced in all hospitals to prevent ER nurses from accumulating excess workload [28]. Mental support services and stress management training must be ubiquitous to meet ER work's psychological demands. Moreover, additional motivation-enhancing strategies, such as recognition programs and opportunities for professional development, need to be implemented to maintain high performance in triage tasks. Lastly, training programs should adopt high-fidelity simulation [29, 30], a method demonstrated to significantly increase the quality of decision-making by nurses in complex scenarios and improve adherence to Emergency Severity Index protocols. These measures will ensure the accuracy of triage performance, optimize workload management, and improve the quality of ER care and patient outcomes.

This study contributes to understanding factors influencing ESI implementation, providing actionable insights for improving triage accuracy and efficiency. However, it is not without limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and future research should employ longitudinal designs to strengthen these findings. Additionally, this study was conducted in a single hospital due to the region's limited adoption of the ESI system. While this hospital was chosen as the only facility on the island and province to implement ESI, the findings may not fully represent the experiences of other hospitals with different settings or those yet to adopt ESI. Future research should include multiple hospitals from various regions to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

Workload is the most significant factor affecting ESI implementation, followed by work stress and motivation.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the management and staff of X Regional General Hospital for their support and cooperation during the data collection process. Special thanks are extended to the emergency department nurses who participated in this study and provided valuable insights that made this research possible.

Ethical Permissions: The health research ethics committee of Sidoarjo Regional General Hospital approved this study (Approval No. 893.3/066/438.5.2.1.1/2023).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this research.

Authors' Contribution: Riu SDM (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (40%); Nursalam N (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Nusi T (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (10%); Yahya IM (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (10%); Rahil NH (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%); Taplo YM (Sixth Author), Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: The authors fully self-funded this research without external funding sources.

The emergency room (ER) is a lifesaving hospital unit for patients who need immediate medical attention. Trauma-related incidents, including traffic accidents, violence, falls, and poisoning, account for more than 5 million deaths worldwide each year, making the ER a key entry point for life-saving interventions and preventing disabilities in affected individuals [1]. The quality of care in the ER significantly impacts patient outcomes, with one key indicator being the effectiveness of triage implementation. Triage is the process of assessing and prioritizing patients based on the severity of their conditions to ensure timely and appropriate treatment. Triage of patients based on the severity system is critical, especially during surges of patient admissions, to lower mortality and morbidity rates. Despite its necessity, triage errors can result in treatment delays, lifelong disabilities, or death, highlighting the essential nature of triage performed well [2, 3].

The emergency severity index (ESI) is one of several triage systems used internationally, and it has been adopted in part due to its precise, structured methodology for stratifying patients into five categories based on the anticipated urgency and resource needs. The ESI identifies patients who need immediate life-saving interventions and considers the resources required to treat their conditions [4]. This approach helps achieve better patient flow and facilitates better resource usage, hence a reproducible standard approach to maximize ER productivity and quality of patient care.

While ESI has benefits, it is not easy to carry out, and it is affected by various factors such as work stress, workload, and motivation of ER nurses. They are at the heart of triage, executing rapid assessments and ensuring patients are prioritized. Yet, worldwide, studies show the accuracy of triage decisions is far from optimal, with up to 56.2% of triage decisions accurate in Taiwan, 59.2% in Brazil, and 58.7% in Pennsylvania [2]. The impact of triage can affect patient outcomes, and the factors contributing to those decisions need to be addressed to improve nurse performance.

Due to emergency care's dynamic and high-stakes nature, ER nurses can face significant work stress. Recurrent exposure to high-risk environments and potentially deadly circumstances may result in psychosocial stress, causing alterations in decisions, faculties, and performance in general [5, 6]. The workload is another key factor; ERs often have high patient density and limited staffing. Overworked nurses may suffer from cognitive fatigue, making them more prone to mistakes [7, 8]. In contrast, motivation, which intrinsic and extrinsic factors can influence, plays a significant role in achieving focus, resilience, and job satisfaction among nurses [9]. Knowing how these elements interact with triage implementation will help make ER operations better.

Existing literature has examined the impact of work stress, workload, and motivation on the performance of nurses in different environments. For instance, Lu et al. emphasized that excessive workload threatens patient safety and staff well-being [9]. At the same time, Toulson et al. highlighted the significance of allocating resources during the triage process [10]. However, research on these factors concerning the implementation of ESI in Indonesia is limited. There is a need for more investigation of the gap to develop strategies to improve triaging better and faster in the ERs.

This research studies the factors correlated with implementing the ESI triage system, with special attention to work stress, workload, and motivation. Findings will help inform hospital administrators and policymakers on targeted interventions by identifying significant influences on triage performance. Key areas that can be addressed include improving nurse performance and reducing errors, which ultimately have the potential to improve patient outcomes in emergency care settings. Implementing the ESI triage system is vital to maximizing ER operations and patients. Yet it is affected by multiple, interconnected drivers, including stress at work, workload, and motivation.

Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap in the knowledge base by exploring these antecedents in the ESI context to advance the work on enhancing the quality of care in an emergency setting.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Sidoarjo Regional General Hospital, a tertiary-level healthcare facility with a well-established emergency department, in 2023. The study population consisted of all nurses employed in the emergency department for at least six months who had direct involvement in triage decision-making and were familiar with the ESI system. A minimum sample size of 68 participants was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (a medium effect size=0.15, α=0.05, and 1-β=0.8), considering three explanatory variables (work stress, workload, and motivation). The final sample included 72 nurses, exceeding the minimum requirement. However, the availability of emergency nurses within the emergency department limited further expansion of the sample size [11].

Instrument

The study measured four parameters; Work stress, workload, motivation, and ESI implementation.

Work stress: was assessed using a validated questionnaire adapted from Djariah et al. This scale comprised 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater stress levels [12]. This study confirmed the reliability of the questionnaire with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.

Workload: was evaluated using a questionnaire adapted from Wicaksono et al. This instrument included 15 items assessing workload components, such as time pressure, task complexity, and patient-to-nurse ratios. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale [13]. The instrument demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89).

Motivation: was measured using a scale adapted from Indrayanti et al. The 12-item questionnaire assessed intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors, such as job satisfaction, recognition, and professional growth opportunities. Responses were captured on a 5-point Likert scale [14], with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

ESI implementation: was assessed using a researcher-developed questionnaire based on the ESI triage algorithm. The instrument comprised 14 items evaluating nurses’ adherence to ESI protocols and decision-making accuracy. Two experts in emergency nursing and healthcare management tested the initial questionnaire's content validity, achieving a validity score of 70%. After removing five invalid items, the final instrument demonstrated strong reliability with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

Procedure

Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participation was voluntary, and respondents could withdraw at any time without penalty. Data confidentiality was ensured by anonymizing all responses and securely storing the data in a password-protected system accessible only to the research team. Data collection was conducted over four weeks. Participants were recruited through announcements and face-to-face invitations during shift handovers. Data were collected using self-administered questionnaires in a private, quiet area within the hospital to ensure confidentiality and minimize disruptions.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26 software and the relationships between work stress, workload, motivation, and ESI implementation were assessed using multiple linear regression analysis. The regression model included the work stress, workload, and motivation and ESI implementation at p<0.05.

Findings

The majority of samples were male (52.8%), between 26 and 35 years old (51.4%), with a vocational degree (72.2%), and married (95.8%; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency distribution of respondents by gender, age, education level, length of work, followed training and marital status

The descriptive analysis revealed moderate levels of work stress (26.63±6.47), workload (119.08±14.13), and motivation (100.10±12.10) among participants, with ESI implementation scores averaging 49.43±5.75.

All three explanatory parameters were positively associated with ESI implementation. Work stress was found to have a significant positive relationship with ESI implementation (B=0.24; t=2.51; p=0.015). Workload emerged as the strongest predictor of ESI implementation (B=0.14; t=3.27; p=0.002). Motivation also showed a significant positive relationship with ESI implementation (B=0.1; t=2.04; p=0.046).

The overall regression model was statistically significant (F=9.63; p<0.001), indicating that the combination of work stress, workload, and motivation explained a substantial portion of the variance in ESI implementation. The adjusted R-squared value of 0.27 suggested that 27% of the variability in ESI implementation can be attributed to these three factors.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between work stress, workload, motivation, and implementing the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) in the emergency room. The findings revealed that all three factors, work stress, workload, and motivation, were positively associated with the implementation of ESI. Among these, workload emerged as the most significant factor, underscoring its pivotal role in determining triage efficiency and accuracy.

The study found that workload was the most significant barrier to ESI implementation. This is consistent with prior evidence showing that overload conditions detrimentally affect cognitive performance, speed, and error probability for triage decisions [15-16]. This job is inherently performed under tremendous pressure and requires rapid and accurate evaluation of the patient's condition despite time constraints. When nurses are overwhelmed, their ability to prioritize effectively is compromised, which could jeopardize patient safety. Managing workloads in ER settings requires more than just lowering nurse-to-patient ratios. These include the right balance of delegation of tasks, the use of technology, including electronic health records and triage assistance systems, and an adequate supply of humans and materials. So, adding decision-support systems could help relieve the cognitive load of triage by supplying real-time data and risk assessments. These systems have demonstrated utility in improving triage accuracy and accurate diagnosis in high-acuity settings [15]. The unstable workload varies with patient acuity, time of day, and unexpected emergencies. So, dynamic resource allocation, like activating surge capacity protocols during peak times, is necessary. Training ER staff to adapt effectively to different workload levels and promoting teamwork could also lessen the adverse effects of a high workload on triage performance.

Work stress significantly affects the implementation of ESI, albeit to a lesser degree than workload. ER nurses often operate in unpredictable environments, life-or-death situations, and high emotional demands. Chronic exposure to such stressors can lead to psychological fatigue, reduced attentiveness, and impaired decision-making [17, 18]. Stress management strategies tailored to the unique challenges of ER work are critical. These could include structured debriefing sessions after critical incidents, access to mental health resources, and regular stress management workshops. Additionally, promoting a supportive workplace culture where nurses feel valued and empowered can buffer the adverse effects of stress. For example, team-based approaches to triage, where decision-making responsibility is shared, can reduce individual stress levels and improve the overall quality of care. Another important consideration is the role of stress in triggering defensive or risk-averse behaviors in triage decisions. Stress may lead nurses to over-triage patients, assigning higher acuity levels to avoid potential adverse outcomes. While this may reduce immediate risks, it can strain ER resources and compromise care for genuinely critical patients. Addressing this requires balancing stress mitigation with enhanced training to boost confidence and decision-making accuracy.

Motivation was found to have a significant positive relationship with ESI implementation. Motivated nurses are more likely to approach triage with focus, diligence, and resilience despite the challenges of ER work [19, 20]. Intrinsic motivation, such as professional pride and commitment to patient care, often drives higher engagement and performance. Extrinsic motivators, including recognition, career advancement opportunities, and financial incentives, further reinforce this effect [21]. Hospital administrators can enhance motivation by creating a culture of recognition and reward [22]. Simple gestures, such as acknowledging exemplary performance in triage, can profoundly impact morale. Providing opportunities for career development, such as advanced training in emergency nursing or leadership roles, can also sustain long-term motivation [23]. Interestingly, motivation interacts with both workload and stress. Highly motivated nurses may better manage heavy workloads and cope with stress, demonstrating resilience and adaptability [24]. This suggests that fostering motivation could indirectly mitigate the negative impacts of workload and stress on triage performance.

The interplay between workload, stress, and motivation highlights the complexity of factors influencing ESI implementation. While high workload and stress often have adverse effects, they can be moderated by strong motivation and a supportive work environment. For instance, a motivated nurse under stress might still perform well if supported by a cohesive team and adequate resources [25]. Conversely, low motivation could exacerbate the adverse effects of workload and stress, leading to suboptimal triage outcomes [26]. This dynamic interplay suggests the need for integrated interventions. Addressing these factors in isolation is unlikely to yield significant improvements. Instead, hospitals should adopt a comprehensive approach, simultaneously managing workload, reducing stress, and fostering motivation [27].

This research has several practical and policy implications. Workload management systems, which may encompass dynamic scheduling and real-time resource monitoring, should be introduced in all hospitals to prevent ER nurses from accumulating excess workload [28]. Mental support services and stress management training must be ubiquitous to meet ER work's psychological demands. Moreover, additional motivation-enhancing strategies, such as recognition programs and opportunities for professional development, need to be implemented to maintain high performance in triage tasks. Lastly, training programs should adopt high-fidelity simulation [29, 30], a method demonstrated to significantly increase the quality of decision-making by nurses in complex scenarios and improve adherence to Emergency Severity Index protocols. These measures will ensure the accuracy of triage performance, optimize workload management, and improve the quality of ER care and patient outcomes.

This study contributes to understanding factors influencing ESI implementation, providing actionable insights for improving triage accuracy and efficiency. However, it is not without limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and future research should employ longitudinal designs to strengthen these findings. Additionally, this study was conducted in a single hospital due to the region's limited adoption of the ESI system. While this hospital was chosen as the only facility on the island and province to implement ESI, the findings may not fully represent the experiences of other hospitals with different settings or those yet to adopt ESI. Future research should include multiple hospitals from various regions to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

Workload is the most significant factor affecting ESI implementation, followed by work stress and motivation.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the management and staff of X Regional General Hospital for their support and cooperation during the data collection process. Special thanks are extended to the emergency department nurses who participated in this study and provided valuable insights that made this research possible.

Ethical Permissions: The health research ethics committee of Sidoarjo Regional General Hospital approved this study (Approval No. 893.3/066/438.5.2.1.1/2023).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this research.

Authors' Contribution: Riu SDM (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (40%); Nursalam N (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Nusi T (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (10%); Yahya IM (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (10%); Rahil NH (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (10%); Taplo YM (Sixth Author), Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: The authors fully self-funded this research without external funding sources.

Keywords:

Emergency Room Visits [MeSH], Motivation [MeSH], Health Services [MeSH], Hospitals [MeSH], Triage [MeSH], Workload [MeSH]

References

1. Nusi T, Lestari Y, Suryanto S. Overview of the efficiency of using the triage Emergency Severity Index (ESI) in emergency installations: A systematic review. JURNAL AISYAH: JURNAL ILMU KESEHATAN. 2023;8(2):1051-60. [Link] [DOI:10.30604/jika.v8i3.2070]

2. Ivanov O, Wolf L, Brecher D, Lewis E, Masek K, Montgomery K, et al. Improving ED emergency severity index acuity assignment using machine learning and clinical natural language processing. J Emerg Nurs. 2012;47(2):265-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2020.11.001]

3. Fernandes M, Mendes R, Vieira SM, Leite F, Palos C, Johnson A, et al. Risk of mortality and cardiopulmonary arrest in critical patients presenting to the emergency department using machine learning and natural language processing. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230876. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0230876]

4. Silva JAD, Emi AS, Leão ER, Lopes M, Okuno MFP, Batista REA. Emergency severity index: Accuracy in risk classification. Einstein. 2017;15(4):421-7. [Portuguese] [Link] [DOI:10.1590/s1679-45082017ao3964]

5. Mulyadi M, Dedi B, Hou WL, Huang IC, Lee BO. Nurses' experiences of emergency department triage during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2022;54(1):15-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jnu.12709]

6. Trudgill DIN, Gorey KM, Donnelly EA. Prevalent posttraumatic stress disorder among emergency department personnel: Rapid systematic review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2020;7(1):89. [Link] [DOI:10.1057/s41599-020-00584-x]

7. Abellanoza A, Provenzano-Hass N, Gatchel RJ. Burnout in ER nurses: Review of the literature and interview themes. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2018;23(1):e12117. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jabr.12117]

8. Park S, Yoo J, Lee Y, DeGuzman PB, Kang MJ, Dykes PC, et al. Quantifying emergency department nursing workload at the task level using NASA-TLX: An exploratory descriptive study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2024;74:101424. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2024.101424]

9. Lu J, Xu P, Ge J, Zeng H, Liu W, Tang P. Analysis of factors affecting psychological resilience of emergency room nurses under public health emergencies. Inquiry. 2023;60:00469580231155296. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/00469580231155296]

10. Toulson K, Laskowski-Jones L, McConnell LA. Implementation of the five-level emergency severity index in a level I trauma center emergency department with a three-tiered triage scheme. J Emerg Nurs. 2005;31(3):259-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2005.04.022]

11. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149-60. [Link] [DOI:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149]

12. Djariah AA, Sumiaty, Andayanie E. Relationship between knowledge, attitude, and work motivation of nurses and the implementation of patient safety in the inpatient room of Makassar City hospital in 2020. Window Public Health J. 2020;1(4):317-26. [Indonesian] [Link]

13. Wicaksono A, Rumengan G, Ulfa L. Analysis of the influence of work stress, workload, work rewards and sanctions on work performance of inpatient nurses at x hospital, Bogor City, West Java Province in 2022. JURNAL MANAJEMEN DAN ADMINISTRASI RUMAH SAKIT INDONESIA. 2022;6(2):174-81. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.52643/marsi.v6i2.2579]

14. Indrayanti SR, Wati NMN, Devhy NLP. The relationship between caring leadership of the room head and nurses' work motivation in the integrated intensive care unit. Sci J Nurs. 2022;8(4):520-7. [Indonesian] [Link] [DOI:10.33023/jikep.v8i4.1021]

15. Dippenaar E. Reliability and validity of three international triage systems within a private health-care group in the Middle East. Int Emerg Nurs. 2020;51:100870. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100870]

16. Wang X, Blumenthal HJ, Hoffman D, Benda N, Kim T, Perry S, et al. Modeling patient-related workload in the emergency department using electronic health record data. Int J Med Inform. 2021;150:104451. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104451]

17. Ardıç M, Ünal Ö, Türktemiz H. The effect of stress levels of nurses on performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of motivation. J Res Nurs. 2022;27(4):330-40. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/17449871211070982]

18. Yuwanich N, Akhavan S, Nantsupawat W, Martin L. Experiences of occupational stress among emergency nurses at private hospitals in Bangkok, Thailand. Open J Nurs. 2017;7(6):657-70. [Link] [DOI:10.4236/ojn.2017.76049]

19. Gunawan NPIN, Hariyati RTS, Gayatri D. Motivation as a factor affecting nurse performance in regional general hospitals: A factors analysis. ENFERMERÍA CLÍNICA. 2019;29(2):515-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.04.078]

20. Daba L, Beza L, Kefyalew M, Teshager T, Wondimneh F, Bidiru A, et al. Job performance and associated factors among nurses working in adult emergency departments at selected public hospitals in Ethiopia: A facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):312. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-01979-w]

21. Li C, Niu Y, Xin Y, Hou X. Emergency department nurses' intrinsic motivation: A bridge between empowering leadership and thriving at work. Int Emerg Nurs. 2024;77:101526. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2024.101526]

22. Karaferis D, Aletras V, Raikou M, Niakas D. Factors influencing motivation and work engagement of healthcare professionals. Mater Sociomed. 2022;34(3):216-24. [Link] [DOI:10.5455/msm.2022.34.216-224]

23. Mohammed SA, Al Jaffane A, Al Qahtani M. Motivating factors influencing the career advancement of nurses into nursing management positions. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2024;20:100751. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2024.100751]

24. Han P, Duan X, Jiang J, Zeng L, Zhang P, Zhao S. Experience in the development of nurses' personal resilience: A meta-synthesis. Nurs Open. 2023;10(5):2780-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/nop2.1556]

25. Jankelová N, Joniaková Z. Communication skills and transformational leadership style of first-line nurse managers in relation to job satisfaction of nurses and moderators of this relationship. Healthcare. 2021;9(3):346. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare9030346]

26. Bijani M, Khaleghi AA. Challenges and barriers affecting the quality of triage in emergency departments: A qualitative study. Galen Med J. 2019;8:e1619. [Link] [DOI:10.31661/gmj.v8i0.1619]

27. Al Ammar MI, Dallak ZM, Alyanbaawi L, Alsaedi AS, Al Rashidi HM, Alshahrani M, et al. Impact of triage nurse training on accuracy and efficiency: A systematic review-based study. Evol Stud Imaginative Cult. 2024;82(S1):1147-61. [Link] [DOI:10.70082/esiculture.vi.1267]

28. Griffiths P, Saville C, Ball J, Jones J, Pattison N, Monks T, et al. Nursing workload, nurse staffing methodologies and tools: A systematic scoping review and discussion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;103:103487. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103487]

29. Vafadar Z, Javadzade H, Behzadnia M, Moayed M. Effects of interdisciplinary education about war victim triage on knowledge and practice of healthcare science students. Iran J War Public Health. 2023;15(4):375-80. [Link]

30. Tonapa SI, Mulyadi M, Ho KHM, Efendi F. Effectiveness of using high-fidelity simulation on learning outcomes in undergraduate nursing education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(2):444-58. [Link]