Volume 16, Issue 3 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(3): 233-238 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/05/13 | Accepted: 2024/06/15 | Published: 2024/09/28

Received: 2024/05/13 | Accepted: 2024/06/15 | Published: 2024/09/28

How to cite this article

Hami M, Mohammad Hassan F. Effect of Judo Training on Life Expectancy, Motivation, and Mental Health of Blind and Visually Impaired Veterans in Tehran. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (3) :233-238

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1460-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1460-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

M. Hami *1, F. Mohammad Hassan2

1- Department of Sports Management, Islamic Azad University, Sari Branch, Sari, Iran

2- Department of Sport Management, Sport Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Sport Management, Sport Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (546 Views)

Introduction

The need for exercise and its continuity is felt much more acutely by disabled individuals than by non-disabled ones. Undoubtedly, exercise is a factor that helps integrate disabled people into society and fosters their independence in performing activities. Nowadays, disabled individuals participate in social activities and more tournaments, allowing them to demonstrate their abilities and skills to society. Disabled individuals have their histories, and Canada is a prominent nation in this regard. For example, in 1973, Eugene Reimer was selected as the outstanding male athlete of the year in Canada and awarded honors to a disabled athlete. Three years later, the first disabled competition was held in Edmonton, Alberta, featuring annual wheelchair games as well as sports for the blind and amputees. After World War I, especially among the blind and amputees, exercise was applied as a form of treatment. The innovation of disabled sports has a history of about 100 years, during which the positive influence of exercise on mental health was recognized in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Physically disabled individuals, as members of society, need exercise and motor programs. Martial arts exercises typically integrate physical activity with components of mindfulness, which may be effective in reducing anxiety, promoting self-regulation, and improving balance and motor coordination [1]. Given the increasing importance of movement activities and exercises for people with disabilities, significant efforts have been made to identify and reduce the risks associated with their sports activities. The main objective of motor programs for people with disabilities is to preserve or restore their health as much as possible. Through the continuum of specific movements, their capabilities will be enhanced over time, resulting in a reduction of complications associated with severe disabilities. Additionally, participation in sports communities and preventing the isolation of disabled individuals is another objective of engaging in exercise [2].

In the past three decades, efforts in the field of sports for disabled individuals and appropriate physical activities have grown considerably. Research reviews suggest that exercise and physical activity can enhance both physical and mental health. Exercise and physical activity can improve the overall spirit and well-being of individuals suffering from depression and anxiety. Furthermore, increased self-esteem, social awareness, and self-belief among disabled individuals can lead to their empowerment [3].

Shah et al. noted that developing countries face many challenges in addressing political, social, and economic problems. One significant challenge is ensuring the well-being and health of the population. Government healthcare planners also encounter numerous difficulties in providing nutrition, sanitation, immunization, and clean water. This is why mental health often receives lower priority. Nevertheless, mental health disorders continue to increase in their impact [4].

According to a survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is projected to be a major cause of disability by 2030, with approximately 280 million people affected by depression worldwide [5].

Kamali & Ashori reported that individuals who are blind are more likely to have a low quality of life [6]. Many studies focus on various dimensions of quality of life, such as social well-being, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-concept. In contrast, other studies refer to health-related quality of life [7]. Quality of life encompasses people’s perceptions of their living conditions within the cultural context and value system, in which they live and is determined by their goals, concerns, expectations, and standards. It includes the domains of physical, psychological, spiritual, beliefs, independence, and environment [5]. Some blind and visually impaired individuals have a less favorable lifestyle than their sighted peers [8]. As a result, these individuals may experience serious consequences for their quality of life compared to their sighted counterparts.

Ramees stated that performing isometric exercises is one of the most important types of exercise in sports due to its economic nature and the minimal space required. This type of exercise may be suitable for individuals of all ages and genders, including the elderly. It can also be performed with or without equipment. Therefore, training in isometric exercises could be beneficial for blind individuals [9].

Rector et al. expressed that people who are blind or have low vision may face challenges in participating in exercise due to inaccessibility or lack of experience. They employed Value Sensitive Design (VSD) to explore the potential of technology to enhance exercise opportunities for individuals who are blind or have low vision. They conducted 20 semi-structured interviews about exercise and technology with ten individuals who were blind or had low vision, as well as ten individuals who facilitated fitness for blind or low-vision people. Based on the interviews and surveys, they identified opportunities for technology development in four areas, including mainstream exercise classes, exercise with sighted guides, rigorous outdoor activities, and navigation of exercise spaces [10].

Kondirolli & Sunder state that mental well-being is critical because it is a key determinant of several socio-economic outcomes, such as premature mortality, lower life expectancy, and a higher risk of other communicable and non-communicable diseases [11].

The points mentioned above indicate that physical activity and exercise play a key role in enhancing the psychological and physical health of both disabled and non-disabled individuals. Regular exercise has a significant effect on reducing feelings of stress, depression, anger, and mental disability. Sports training and competitions improve the living conditions of people with visual disabilities and thus positively impact the lives of all those who interact with them. Individuals with visual impairments who engage in gentle and regular (sustained) physical activities will experience improvements in their overall wellness and general health. Those who increase the duration, continuity, and intensity of their activities will benefit from even greater advantages. Judo is a dynamic, physically demanding sport that requires complex skills and tactical excellence for success [12].

Judo is a worldwide sport that serves as a primary competition in the Olympic Games and the World Judo Championship, with different age categories available for each competition. The level of physical fitness, tactical skills, and techniques required in judo is high, as it involves high-intensity, short-duration exercises performed periodically. Very few studies have examined the effects of judo exercises on non-athletes [13].

This study aimed to investigate the impact of eight weeks of judo training on life expectancy, motivation, and mental health among blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran.

Materials and Methods

The present experimental study was conducted on 100 blind and visually impaired male non-athletes from the eight-year Holy Defense War in Tehran Province, Iran in 2023. Forty visually impaired men from Tehran Province who had no prior training experience were voluntarily selected and then randomly assigned to the experimental (20 participants) and control (20 participants) groups. The inclusion criteria were age between 50 and 60 years, no history of specialized sports training, no history of cardiovascular diseases, and no regular physical activity in the past year.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, indicating their understanding of the nature, procedures, and potential risks of the research. Additionally, participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time if they felt unable or unwilling to continue.

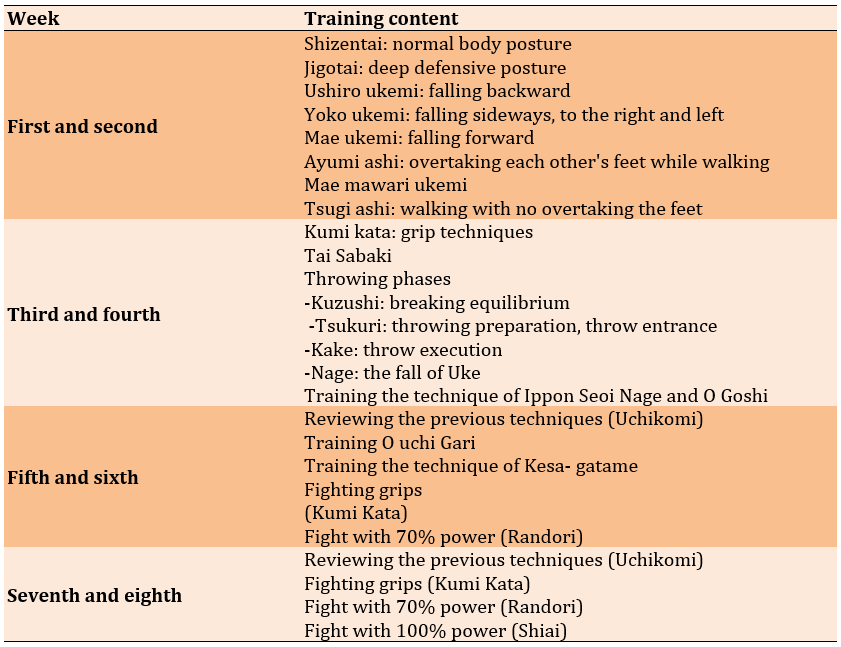

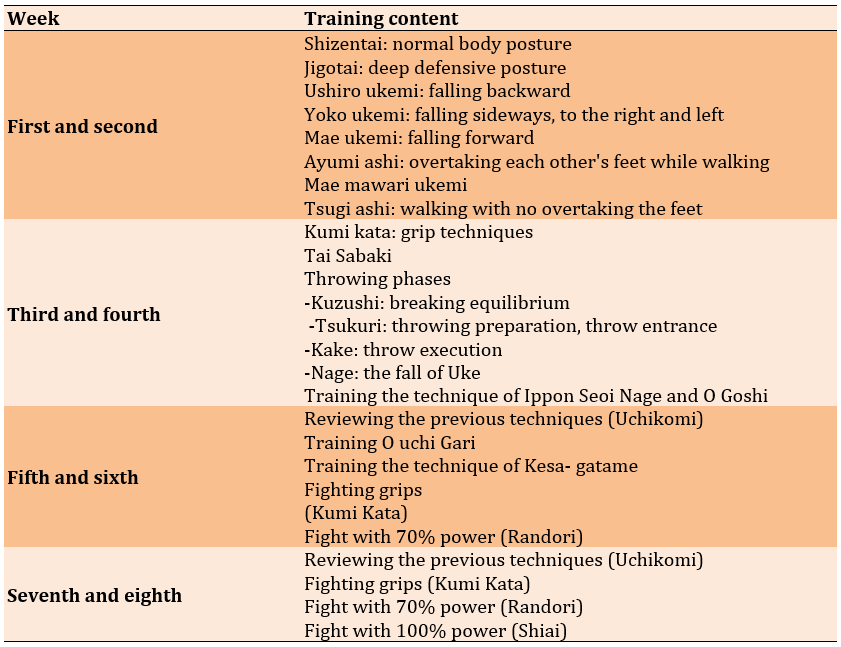

We used an eight-week judo training protocol consisted of three 90-minute sessions per week. Each session began with a 20-minute warm-up, followed by a 60-minute technical training phase, and concluded with a 10-minute cool-down. During the initial two weeks, the focus was on mastering fundamental Judo principles and ground techniques. In weeks three and four, the emphasis shifted to acquiring the Ippon Seoi Nage, O Goshi, and Kesa-gatame techniques. In the following two weeks, participants reviewed previously learned techniques (Uchikomi) and were introduced to Ouchi Gari, Kumi Kata, and Randori (light sparring) at 70% intensity. The final two weeks culminated in a review of the learned techniques and the full-intensity practice of Shiai (full-contact competition; Table 1).

Table 1. An 8-week judo training protocol

The Miller Hope Scale (MHS), developed by Miller and Powers, was the first tool used. The initial version of the questionnaire included 40 items, which was later expanded to 48 items. This questionnaire uses a Likert scale scored from strongly disagree (score one) to strongly agree (score five). The minimum and maximum scores for each individual are 48 and 240, respectively. In this questionnaire, items 11, 13, 16, 18, 25, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34, 38, 39, 47, and 48 are scored in reverse.

The second measurement tool used was Willis’s Sport Attitude Inspection Questionnaire (SAI), which assessed players’ characteristics in terms of three motivational dimensions, including success motivation (items 1-17), failure avoidance motivation (items 18-28), and power motivation (items 29-40). These were measured on a five-point Likert scale.

To measure mental health, the 28-question Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was utilized, which consisted of four subtests, each containing seven items. The items in each subtest are consecutive, such that items 1 to 7 relate to physical symptoms, items 8 to 14 pertain to anxiety and insomnia, questions 15 to 20 address social functioning disorders, and items 22 to 28 focus on depression. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the life expectancy questionnaire, motivation, and mental health were 0.82, 0.92, and 0.91, respectively.

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data using the mean and standard deviation. A paired t-test was used to compare the mean scores within each group (pre-test and post-test). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilized to compare the differences between the two separate groups.

Findings

A total of 100 subjects participated in the study and their mean age was 55.71±4.12 years.

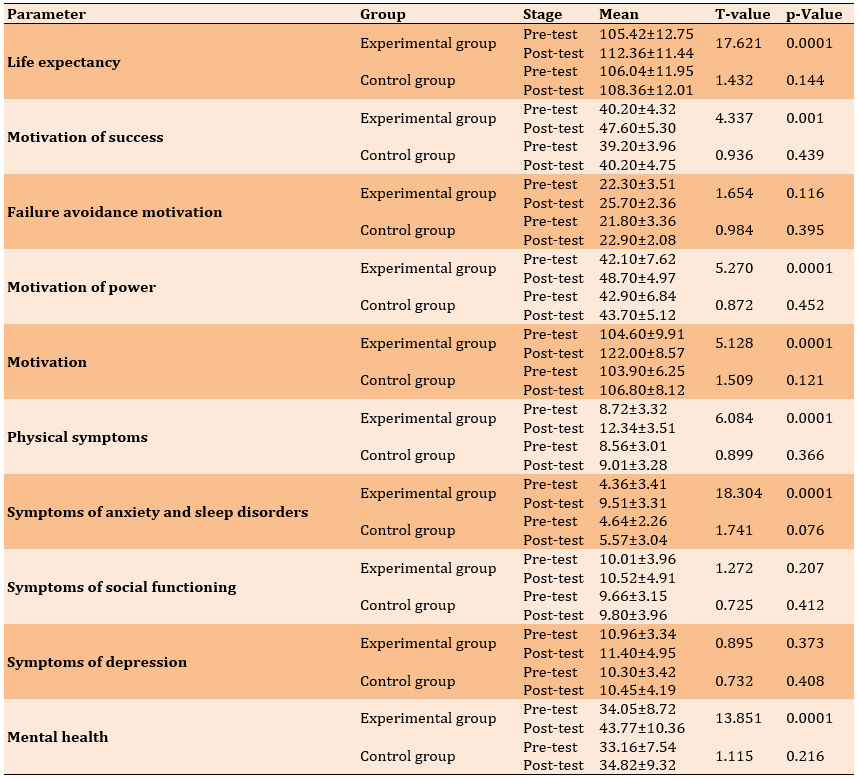

To compare the life expectancy, motivation, and mental health of blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran before and after eight weeks of judo training, the parametric t-test for two dependent groups was used, due to the normal distribution of the data.

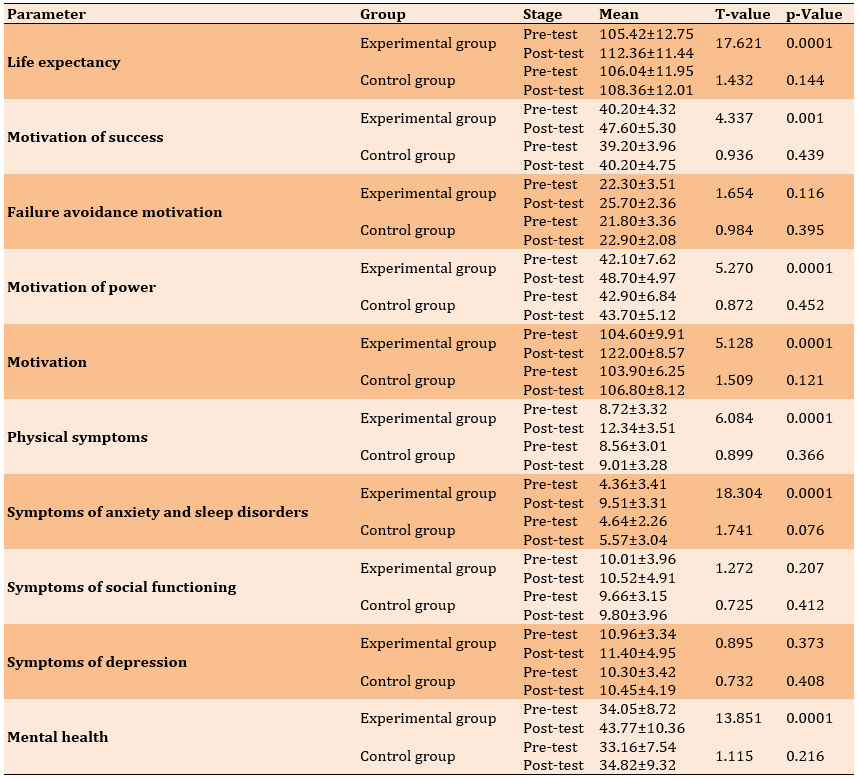

There was a significant difference in life expectancy, success motivation, power motivation, total motivation, physical symptoms, anxiety symptoms, sleep disorders, and total mental health of blind individuals in the experimental group before and after eight weeks of judo training (p<0.01). However, no significant difference was observed in the components of failure avoidance motivation, symptoms of social functioning, and symptoms of depression. Moreover, no significant differences were found in any of these parameters in the control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of mean life expectancy, motivation, and mental health scores of blind and visually impaired war veterans in Tehran before and after 8 weeks of judo training in the experimental and control groups

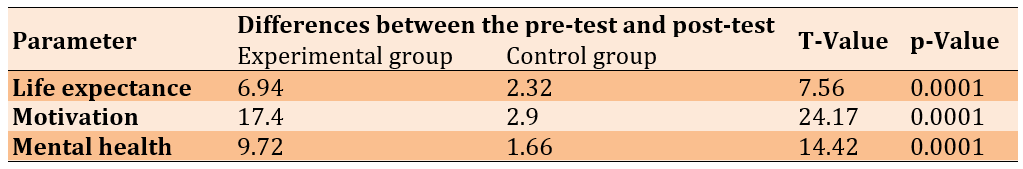

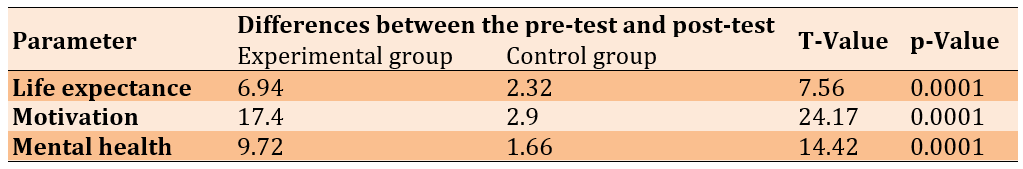

The results of the ANCOVA conducted to compare the pre- and post-test differences demonstrated that after eight weeks of training, life expectancy, motivation, and mental health showed significant differences between the experimental and control groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the differences between the experimental and control groups

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the impact of eight weeks of judo training on life expectancy, motivation, and mental health among blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran. The observed improvements in life expectancy, mental health, and motivation among blind and visually impaired veterans through judo training underscored the potential of adapted physical activity as a critical component of rehabilitation and long-term care. These findings advocate for the integration of judo and similar programs into comprehensive rehabilitation plans for this population. Moreover, policymakers should consider allocating resources to support the development and implementation of accessible sports programs for veterans with visual impairments. Such initiatives can significantly enhance the overall well-being and quality of life of this underserved group.

There was a significant difference in the life expectancy of blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran before and after eight weeks of judo training. This difference can be explained by the fact that sports provide a means for blind and visually impaired veterans to overcome the physical, mental, psychological, and social pressures caused by living in today’s challenging world, leading to greater life expectancy. The benefits of engaging in physical activities for disabled athletes have been established. Exercise can positively affect both the physical and psychological dimensions of individuals, thereby increasing their life expectancy [14]. Additionally, participating in sports activities offers benefits for disabled individuals, such as enhanced strength and resilience in facing life’s challenges, as well as increased self-confidence, self-efficacy, and quality of life—all of which contribute to improved life expectancy [15].

There was a significant difference in the mental health of blind and visually impaired individuals injured during the war in Tehran before and after eight weeks of judo training. However, there was no significant difference in the two components of social functioning symptoms and depression symptoms. These results are inconsistent with the findings of Ross & Hayes [16], Di Lorenzo et al. [17], Guszkowska [18], Akandere & Tekin [19], Giacobbi et al. [20], and Knechtle et al. [21], indicating a positive correlation between exercise and the subscales of physical symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and mental health sleep disorders. This result could be explained by the valuable role that exercise plays in mental health due to its positive mental and physical effects. Additionally, Di Lorenzo et al. [17] and Akandere & Tekin [19] confirm the effect of exercise on reducing anxiety. Studies have shown that exercise increases mental health, enhances self-worth, reduces anxiety and depression [20], and improves mental strength [22]. The lack of significant findings regarding the two components of social functioning symptoms and depression symptoms may be attributed to research indicating that visual impairment can lead to feelings of inferiority and disability in individuals, resulting in greater concerns about their future and a negative self-attitude among blind individuals.

These individuals believe that ordinary people perform far better than they do, and this perception affects their social functioning and contributes to depression. Social isolation and a lack of adequate social support lead to low self-esteem and problems in social functioning, which in turn cause depression.

There was a significant difference in the competitive motivation of blind and visually impaired individuals in Tehran who were injured during the Iran-Iraq War before and after eight weeks of judo training. This result is consistent with the findings of Malone et al. [23] and Iezzoni [24].

In line with the results of this study, Willis [25] demonstrated that there is a significant difference between the motivation to compete in directly competitive sports and those that are not directly competitive. The need for exercise and its health impact on people with disabilities is particularly pronounced. Sports can empower disabled individuals, helping them to integrate into society and become more independent. However, it can be stated that many disabled individuals have less motivation and enthusiasm for group work and social activities due to their withdrawal from society. People who follow a regular exercise program often feel energized. Additionally, exercise helps the body transport more oxygen to key organs such as the lungs, brain, heart, and muscles. Furthermore, it enhances mental motivation [26]. The need for exercise and its continuation is especially important for disabled individuals. Undoubtedly, sports play a crucial role in integrating disabled people into society and fostering their independence in daily activities.

While the present study demonstrated the positive impact of judo training on blind and visually impaired veterans, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. The sample size may be considered relatively small, which could potentially restrict the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the study’s eight weeks may not be sufficient to assess long-term effects. Future research could address these limitations by employing larger sample sizes and conducting longitudinal studies to examine the sustained benefits of judo training. Additionally, investigating the effectiveness of judo training in comparison to other forms of physical activity would provide valuable insights into the optimal interventions for this population.

Conclusion

Eight weeks of judo training positively affects life expectancy, mental health, and competitive motivation of blind and visually impaired veterans.

Acknowledgments: The collaboration of all participants is greatly appreciated.

Ethical Permissions: This study was conducted in accordance with research ethics guidelines.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Hami M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (60%); Mohammad Hassan F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: This study received no funding from the public and non-profit sectors.

The need for exercise and its continuity is felt much more acutely by disabled individuals than by non-disabled ones. Undoubtedly, exercise is a factor that helps integrate disabled people into society and fosters their independence in performing activities. Nowadays, disabled individuals participate in social activities and more tournaments, allowing them to demonstrate their abilities and skills to society. Disabled individuals have their histories, and Canada is a prominent nation in this regard. For example, in 1973, Eugene Reimer was selected as the outstanding male athlete of the year in Canada and awarded honors to a disabled athlete. Three years later, the first disabled competition was held in Edmonton, Alberta, featuring annual wheelchair games as well as sports for the blind and amputees. After World War I, especially among the blind and amputees, exercise was applied as a form of treatment. The innovation of disabled sports has a history of about 100 years, during which the positive influence of exercise on mental health was recognized in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Physically disabled individuals, as members of society, need exercise and motor programs. Martial arts exercises typically integrate physical activity with components of mindfulness, which may be effective in reducing anxiety, promoting self-regulation, and improving balance and motor coordination [1]. Given the increasing importance of movement activities and exercises for people with disabilities, significant efforts have been made to identify and reduce the risks associated with their sports activities. The main objective of motor programs for people with disabilities is to preserve or restore their health as much as possible. Through the continuum of specific movements, their capabilities will be enhanced over time, resulting in a reduction of complications associated with severe disabilities. Additionally, participation in sports communities and preventing the isolation of disabled individuals is another objective of engaging in exercise [2].

In the past three decades, efforts in the field of sports for disabled individuals and appropriate physical activities have grown considerably. Research reviews suggest that exercise and physical activity can enhance both physical and mental health. Exercise and physical activity can improve the overall spirit and well-being of individuals suffering from depression and anxiety. Furthermore, increased self-esteem, social awareness, and self-belief among disabled individuals can lead to their empowerment [3].

Shah et al. noted that developing countries face many challenges in addressing political, social, and economic problems. One significant challenge is ensuring the well-being and health of the population. Government healthcare planners also encounter numerous difficulties in providing nutrition, sanitation, immunization, and clean water. This is why mental health often receives lower priority. Nevertheless, mental health disorders continue to increase in their impact [4].

According to a survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is projected to be a major cause of disability by 2030, with approximately 280 million people affected by depression worldwide [5].

Kamali & Ashori reported that individuals who are blind are more likely to have a low quality of life [6]. Many studies focus on various dimensions of quality of life, such as social well-being, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-concept. In contrast, other studies refer to health-related quality of life [7]. Quality of life encompasses people’s perceptions of their living conditions within the cultural context and value system, in which they live and is determined by their goals, concerns, expectations, and standards. It includes the domains of physical, psychological, spiritual, beliefs, independence, and environment [5]. Some blind and visually impaired individuals have a less favorable lifestyle than their sighted peers [8]. As a result, these individuals may experience serious consequences for their quality of life compared to their sighted counterparts.

Ramees stated that performing isometric exercises is one of the most important types of exercise in sports due to its economic nature and the minimal space required. This type of exercise may be suitable for individuals of all ages and genders, including the elderly. It can also be performed with or without equipment. Therefore, training in isometric exercises could be beneficial for blind individuals [9].

Rector et al. expressed that people who are blind or have low vision may face challenges in participating in exercise due to inaccessibility or lack of experience. They employed Value Sensitive Design (VSD) to explore the potential of technology to enhance exercise opportunities for individuals who are blind or have low vision. They conducted 20 semi-structured interviews about exercise and technology with ten individuals who were blind or had low vision, as well as ten individuals who facilitated fitness for blind or low-vision people. Based on the interviews and surveys, they identified opportunities for technology development in four areas, including mainstream exercise classes, exercise with sighted guides, rigorous outdoor activities, and navigation of exercise spaces [10].

Kondirolli & Sunder state that mental well-being is critical because it is a key determinant of several socio-economic outcomes, such as premature mortality, lower life expectancy, and a higher risk of other communicable and non-communicable diseases [11].

The points mentioned above indicate that physical activity and exercise play a key role in enhancing the psychological and physical health of both disabled and non-disabled individuals. Regular exercise has a significant effect on reducing feelings of stress, depression, anger, and mental disability. Sports training and competitions improve the living conditions of people with visual disabilities and thus positively impact the lives of all those who interact with them. Individuals with visual impairments who engage in gentle and regular (sustained) physical activities will experience improvements in their overall wellness and general health. Those who increase the duration, continuity, and intensity of their activities will benefit from even greater advantages. Judo is a dynamic, physically demanding sport that requires complex skills and tactical excellence for success [12].

Judo is a worldwide sport that serves as a primary competition in the Olympic Games and the World Judo Championship, with different age categories available for each competition. The level of physical fitness, tactical skills, and techniques required in judo is high, as it involves high-intensity, short-duration exercises performed periodically. Very few studies have examined the effects of judo exercises on non-athletes [13].

This study aimed to investigate the impact of eight weeks of judo training on life expectancy, motivation, and mental health among blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran.

Materials and Methods

The present experimental study was conducted on 100 blind and visually impaired male non-athletes from the eight-year Holy Defense War in Tehran Province, Iran in 2023. Forty visually impaired men from Tehran Province who had no prior training experience were voluntarily selected and then randomly assigned to the experimental (20 participants) and control (20 participants) groups. The inclusion criteria were age between 50 and 60 years, no history of specialized sports training, no history of cardiovascular diseases, and no regular physical activity in the past year.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, indicating their understanding of the nature, procedures, and potential risks of the research. Additionally, participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time if they felt unable or unwilling to continue.

We used an eight-week judo training protocol consisted of three 90-minute sessions per week. Each session began with a 20-minute warm-up, followed by a 60-minute technical training phase, and concluded with a 10-minute cool-down. During the initial two weeks, the focus was on mastering fundamental Judo principles and ground techniques. In weeks three and four, the emphasis shifted to acquiring the Ippon Seoi Nage, O Goshi, and Kesa-gatame techniques. In the following two weeks, participants reviewed previously learned techniques (Uchikomi) and were introduced to Ouchi Gari, Kumi Kata, and Randori (light sparring) at 70% intensity. The final two weeks culminated in a review of the learned techniques and the full-intensity practice of Shiai (full-contact competition; Table 1).

Table 1. An 8-week judo training protocol

The Miller Hope Scale (MHS), developed by Miller and Powers, was the first tool used. The initial version of the questionnaire included 40 items, which was later expanded to 48 items. This questionnaire uses a Likert scale scored from strongly disagree (score one) to strongly agree (score five). The minimum and maximum scores for each individual are 48 and 240, respectively. In this questionnaire, items 11, 13, 16, 18, 25, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34, 38, 39, 47, and 48 are scored in reverse.

The second measurement tool used was Willis’s Sport Attitude Inspection Questionnaire (SAI), which assessed players’ characteristics in terms of three motivational dimensions, including success motivation (items 1-17), failure avoidance motivation (items 18-28), and power motivation (items 29-40). These were measured on a five-point Likert scale.

To measure mental health, the 28-question Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was utilized, which consisted of four subtests, each containing seven items. The items in each subtest are consecutive, such that items 1 to 7 relate to physical symptoms, items 8 to 14 pertain to anxiety and insomnia, questions 15 to 20 address social functioning disorders, and items 22 to 28 focus on depression. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the life expectancy questionnaire, motivation, and mental health were 0.82, 0.92, and 0.91, respectively.

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data using the mean and standard deviation. A paired t-test was used to compare the mean scores within each group (pre-test and post-test). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilized to compare the differences between the two separate groups.

Findings

A total of 100 subjects participated in the study and their mean age was 55.71±4.12 years.

To compare the life expectancy, motivation, and mental health of blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran before and after eight weeks of judo training, the parametric t-test for two dependent groups was used, due to the normal distribution of the data.

There was a significant difference in life expectancy, success motivation, power motivation, total motivation, physical symptoms, anxiety symptoms, sleep disorders, and total mental health of blind individuals in the experimental group before and after eight weeks of judo training (p<0.01). However, no significant difference was observed in the components of failure avoidance motivation, symptoms of social functioning, and symptoms of depression. Moreover, no significant differences were found in any of these parameters in the control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of mean life expectancy, motivation, and mental health scores of blind and visually impaired war veterans in Tehran before and after 8 weeks of judo training in the experimental and control groups

The results of the ANCOVA conducted to compare the pre- and post-test differences demonstrated that after eight weeks of training, life expectancy, motivation, and mental health showed significant differences between the experimental and control groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the differences between the experimental and control groups

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the impact of eight weeks of judo training on life expectancy, motivation, and mental health among blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran. The observed improvements in life expectancy, mental health, and motivation among blind and visually impaired veterans through judo training underscored the potential of adapted physical activity as a critical component of rehabilitation and long-term care. These findings advocate for the integration of judo and similar programs into comprehensive rehabilitation plans for this population. Moreover, policymakers should consider allocating resources to support the development and implementation of accessible sports programs for veterans with visual impairments. Such initiatives can significantly enhance the overall well-being and quality of life of this underserved group.

There was a significant difference in the life expectancy of blind and visually impaired veterans of the Holy Defense War in Tehran before and after eight weeks of judo training. This difference can be explained by the fact that sports provide a means for blind and visually impaired veterans to overcome the physical, mental, psychological, and social pressures caused by living in today’s challenging world, leading to greater life expectancy. The benefits of engaging in physical activities for disabled athletes have been established. Exercise can positively affect both the physical and psychological dimensions of individuals, thereby increasing their life expectancy [14]. Additionally, participating in sports activities offers benefits for disabled individuals, such as enhanced strength and resilience in facing life’s challenges, as well as increased self-confidence, self-efficacy, and quality of life—all of which contribute to improved life expectancy [15].

There was a significant difference in the mental health of blind and visually impaired individuals injured during the war in Tehran before and after eight weeks of judo training. However, there was no significant difference in the two components of social functioning symptoms and depression symptoms. These results are inconsistent with the findings of Ross & Hayes [16], Di Lorenzo et al. [17], Guszkowska [18], Akandere & Tekin [19], Giacobbi et al. [20], and Knechtle et al. [21], indicating a positive correlation between exercise and the subscales of physical symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and mental health sleep disorders. This result could be explained by the valuable role that exercise plays in mental health due to its positive mental and physical effects. Additionally, Di Lorenzo et al. [17] and Akandere & Tekin [19] confirm the effect of exercise on reducing anxiety. Studies have shown that exercise increases mental health, enhances self-worth, reduces anxiety and depression [20], and improves mental strength [22]. The lack of significant findings regarding the two components of social functioning symptoms and depression symptoms may be attributed to research indicating that visual impairment can lead to feelings of inferiority and disability in individuals, resulting in greater concerns about their future and a negative self-attitude among blind individuals.

These individuals believe that ordinary people perform far better than they do, and this perception affects their social functioning and contributes to depression. Social isolation and a lack of adequate social support lead to low self-esteem and problems in social functioning, which in turn cause depression.

There was a significant difference in the competitive motivation of blind and visually impaired individuals in Tehran who were injured during the Iran-Iraq War before and after eight weeks of judo training. This result is consistent with the findings of Malone et al. [23] and Iezzoni [24].

In line with the results of this study, Willis [25] demonstrated that there is a significant difference between the motivation to compete in directly competitive sports and those that are not directly competitive. The need for exercise and its health impact on people with disabilities is particularly pronounced. Sports can empower disabled individuals, helping them to integrate into society and become more independent. However, it can be stated that many disabled individuals have less motivation and enthusiasm for group work and social activities due to their withdrawal from society. People who follow a regular exercise program often feel energized. Additionally, exercise helps the body transport more oxygen to key organs such as the lungs, brain, heart, and muscles. Furthermore, it enhances mental motivation [26]. The need for exercise and its continuation is especially important for disabled individuals. Undoubtedly, sports play a crucial role in integrating disabled people into society and fostering their independence in daily activities.

While the present study demonstrated the positive impact of judo training on blind and visually impaired veterans, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. The sample size may be considered relatively small, which could potentially restrict the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the study’s eight weeks may not be sufficient to assess long-term effects. Future research could address these limitations by employing larger sample sizes and conducting longitudinal studies to examine the sustained benefits of judo training. Additionally, investigating the effectiveness of judo training in comparison to other forms of physical activity would provide valuable insights into the optimal interventions for this population.

Conclusion

Eight weeks of judo training positively affects life expectancy, mental health, and competitive motivation of blind and visually impaired veterans.

Acknowledgments: The collaboration of all participants is greatly appreciated.

Ethical Permissions: This study was conducted in accordance with research ethics guidelines.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Hami M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (60%); Mohammad Hassan F (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: This study received no funding from the public and non-profit sectors.

References

1. Rivera P, Renziehausen J, Garcia JM. Effects of an 8-week judo program on behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder: A mixed-methods approach. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2020;51(5):734-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10578-020-00994-7]

2. Hüttermann S, Memmert D. Moderate movement, more vision: Effects of physical exercise on intentional blindness. Perception. 2012;41(8):963-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1068/p7294]

3. Steinman BA, Nguyen AQD, Pynoos J, Leland NE. Falls-prevention interventions for persons who are blind or visually impaired. Insight. 2011;4(2):83-91. [Link]

4. Shah SM, Sun T, Xu W, Jiang W, Yuan Y. The mental health of China and Pakistan, mental health laws and COVID-19 mental health policies: A comparative review. Gen Psychiatr. 2022;35(5):e100885. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/gpsych-2022-100885]

5. WHO. Depression, 2021 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1. [Link]

6. Kamali N, Ashori M. The effectiveness of orientation and mobility training on the quality of life for students who are blind in Iran. Br J Vis Impair. 2021;41(1):1-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/02646196211019066]

7. Hintermair M. Quality of life of mainstreamed hearing-impaired children: Results of a study with the inventory of life quality of children and youth (ILC). ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR KINDER-UND JUGENDPSYCHIATRIE UND PSYCHOTHERAPIE. 2010;38(3):189-99. [German] [Link] [DOI:10.1024/1422-4917/a000032]

8. Rainey BJ, Burnside G, Harrison JE. Reliability of cervical vertebral maturation staging. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;150(1):98-104. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.12.013]

9. Ramees K. Effect of isometric exercise on explosive strength of blind school students. Abhinav Natl Mon Refereed J Res Arts Educ. 2015;4:28-33. [Link]

10. Rector K, Milne L, Ladner RE, Friedman B, Kientz JA. Exploring the opportunities and challenges with exercise technologies for people who are blind or low-vision. Proceedings of the 17th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility. Lisbon: ASSETS '15; 2015. p. 203-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1145/2700648.2809846]

11. Kondirolli F, Sunder N. Mental health effects of education. Health Econ. 2022;31(Suppl 2):22-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/hec.4565]

12. Degoutte F, Jouanel P, Filaire E. Energy demands during a judo match and recovery. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(3):245-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bjsm.37.3.245]

13. Mohammed MHH, Choi HJ. Effect of an 8-week judo course on muscular endurance, trunk flexibility, and explosive strength of male university students. Sport Mont. 2017;15(3):51-3. [Link] [DOI:10.26773/smj.2017.10.010]

14. Smith B, Sparkes AC. Disability, sport and physical activity: A critical review. In: Watson N, Roulstone A, Thomas C, editors. Routledge handbook of disability studies. London: Routledge; 2012. p. 336-47. [Link]

15. Abdullah MN, Boateng AK, Zawi KM. Coaching athletes with disabilities: General principles for appropriate training methodology. ISN Bull. 2008;1(2):51-8. [Link]

16. Ross CE, Hayes D. Exercise and psychologic well-bing in the community. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;127(4):762-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114857]

17. Di Lorenzo TM, Bargman EP, Stucky-Ropp R, Brassington GS, Frensch PA, Lafontaine T. Long-term effects of aerobic exercise on psychological outcomes. Prev Med. 1999;28(1):75-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1006/pmed.1998.0385]

18. Guszkowska M. Effects of exercise on anxiety, depression and mood. Psychiatr Pol. 2004;38(4):611-20. [Polish] [Link]

19. Akandere M, Tekin A. The effect of physical exercise on anxiety. Sport J. 2005;5(2):245-54. [Link]

20. Giacobbi PR, Hausenblas HA, Frye N. A naturalistic assessment of the relationship between personality, daily life events, leisure-time exercise and mood. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2005;6(1):67-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychsport.2003.10.009]

21. Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Andonie JL, Kohler G. Influence of anthropometry on race performance in extreme endurance triathletes: World challenge Deca iron triathlon 2006. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(10):644-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bjsm.2006.035014]

22. Levy S, Ebbeck V. The exercise and self-esteem model in adult woman: The inclusion of physical acceptance. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2005;6(5):571-84. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychsport.2004.09.003]

23. Malone LA, Barfield JP, Brasher JD. Perceived benefits and barriers to exercise among persons with physical disabilities or chronic health conditions within action or maintenance stages of exercise. Disabil Health J. 2012;5(4):254-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.05.004]

24. Iezzoni LI. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1947-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0613]

25. Willis JD. Three scales to measure competition-related motives in sport. J Sport Psychol. 1982;4(4):338-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/jsp.4.4.338]

26. Jones GC, Rovner BW, Crews JE, Damielson ML. Effects of depressive symptoms on health behavior practices among older adults with vision loss. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54(2):164-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0015910]