Volume 17, Issue 3 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(3): 269-278 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2025/06/15 | Accepted: 2025/07/29 | Published: 2025/08/10

Received: 2025/06/15 | Accepted: 2025/07/29 | Published: 2025/08/10

How to cite this article

Naghizadeh Baghi A, Zare Abandansari M, Pourzabih Sarhamami K, Nobakht F. Foresight in Disability Sport and Strategies for Inclusive Health Policies. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (3) :269-278

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1653-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1653-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Sports Management, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran

2- Department of Sports Management, Faculty of Sport Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

2- Department of Sports Management, Faculty of Sport Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (94 Views)

Introduction

In the evolving global discourse on health equity and inclusive development, sports participation among persons with disabilities (PwD) is increasingly recognized as a critical dimension of sustainable social policy [1]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 16% of the world’s population lives with some form of disability, a figure that rises significantly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to services and infrastructure remains limited. These populations frequently encounter systemic obstacles that constrain their autonomy, social inclusion, and access to physical and mental health resources [2, 3].

Empirical research consistently shows that PwD engage far less in recreational, physical, and cultural activities than the general population. This disparity is shaped by environmental inaccessibility, social stigmatization, and inadequate policy frameworks [4-6]. In Iran, many PwD remain confined to sedentary lifestyles due to a lack of infrastructure and community engagement, spending their leisure time passively [7, 8]. These patterns are associated with an increased risk of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and cancer [9, 10].

Beyond physical health, inclusive sport plays a vital role in supporting identity development, social participation, and psychological resilience. Participation in structured programs has been linked to greater self-esteem, reduced depression, improved mood, and stronger community integration [11-13]. Adaptive sports, like wheelchair basketball serve as arenas for self-expression and collective belonging [6, 14].

Yet, major obstacles remain. Urban environments in LMICs often lack accessible design, adaptive equipment, and qualified instructors [1, 15]. Policies frequently adopt segregated models, perpetuating exclusion [16, 17]. Despite growing awareness, sports participation among PwD remains hindered by structural and attitudinal barriers, particularly in settings like Iran, where there is an uneven distribution of sports resources [18, 19].

Much of Iran’s recent disability sport policy has focused on short-term initiatives, such as the donation of adaptive equipment or isolated community events [14, 20]. These fragmented interventions rarely reflect the lived experiences of PwD or long-term strategic priorities. In this context, foresight methodology offers a proactive tool for envisioning inclusive futures, identifying drivers of change, and anticipating policy challenges [21, 22].

Despite the existence of studies examining barriers to sports participation [23, 24], few have applied systems-level foresight analysis to the field of disability sport, especially in Iran. The lack of a long-term roadmap hinders national efforts to integrate assistive technologies, train human capital, and align urban planning with inclusion goals [7, 25]. As Iran undergoes demographic shifts and technological changes, reactive and fragmented strategies are no longer sufficient [8, 26].

Although research on disability sport has grown in recent years, much of it remains limited to descriptive analyses or examinations of isolated barriers. Few studies address forward-looking strategies that integrate demographic changes, technological advances, and policy reforms with measurable health outcomes. In Iran, this gap is particularly evident, as initiatives for people with disabilities in sport are still largely short-term and event-focused, rather than embedded in long-term, health-oriented strategic planning. Despite rising public and institutional awareness, the use of foresight methodology to guide disability sport development and its role in promoting physical and mental health remains critically underutilized.

Little attention has been paid to the interconnected structural, economic, and policy drivers that can shape equitable participation and reduce health disparities over the next decade. This study addressed this gap by systematically identifying and analyzing the key factors likely to influence the future of disability sport in Iran by 2034. Using a foresight-based approach, it aimed to guide the creation of proactive, inclusive, and context-specific policies that not only expand access but also position sport as an integral component of national health promotion strategies, empowering people with disabilities to be active participants and decision-makers in shaping their health and well-being.

Instrument and Methods

Study design and sample

The foresight-driven study based on scenario planning methodology employed a theoretical applied design. From the theoretical perspective, it aimed to enrich the academic discourse on disability sport by providing conceptual depth and explanatory insights. From the applied perspective, the findings were intended to form a strategic basis for evidence-based planning to enhance sports participation among PwD in Iran.

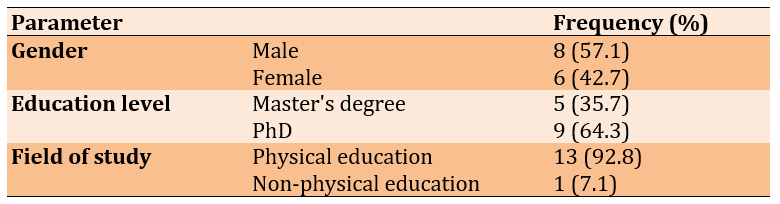

Participants were selected from a national pool of experts in disability sport. The group included senior managers and officials from disability-related sport federations, elite coaches, referees, athletes from different disciplines, and university faculty members with expertise in physical education, sport management, or adapted physical activity. Selection criteria included experience in athletic or administrative roles within disability sport and an academic or research background in foresight studies or disability sport development. Due to the absence of an official database, purposive and criterion-based sampling was used. Recruitment continued until theoretical saturation was reached, resulting in 14 participants.

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants. As the research design relied on expert interviews and Delphi rounds with professionals in disability sport, no clinical or medical interventions were conducted. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses, and their right to withdraw at any stage without penalty was explicitly respected.

Study tools

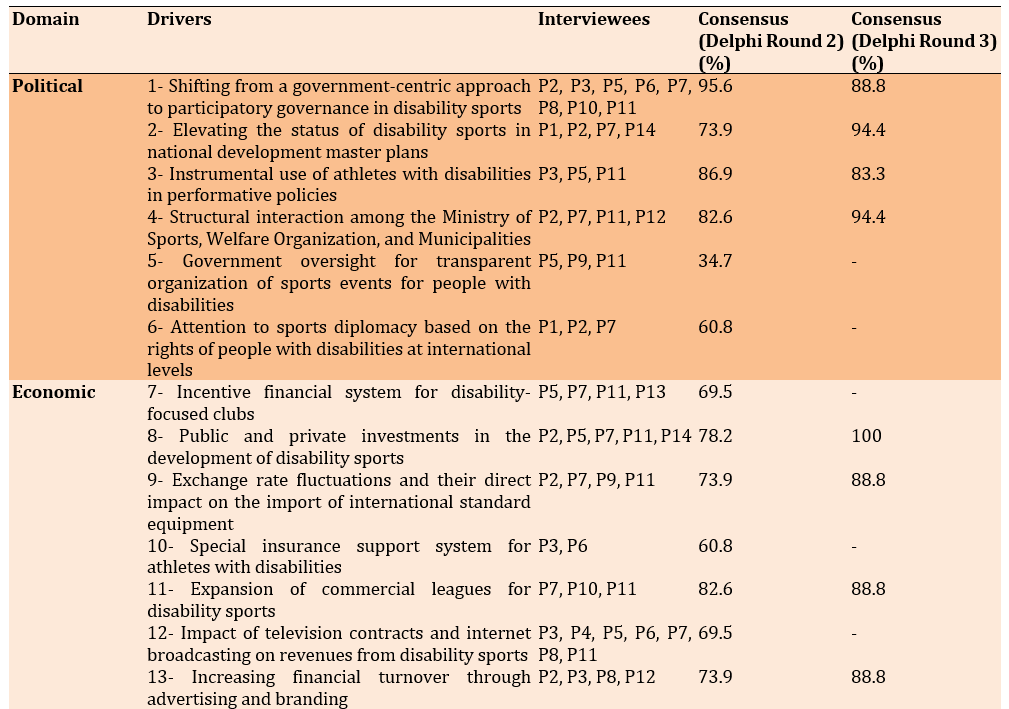

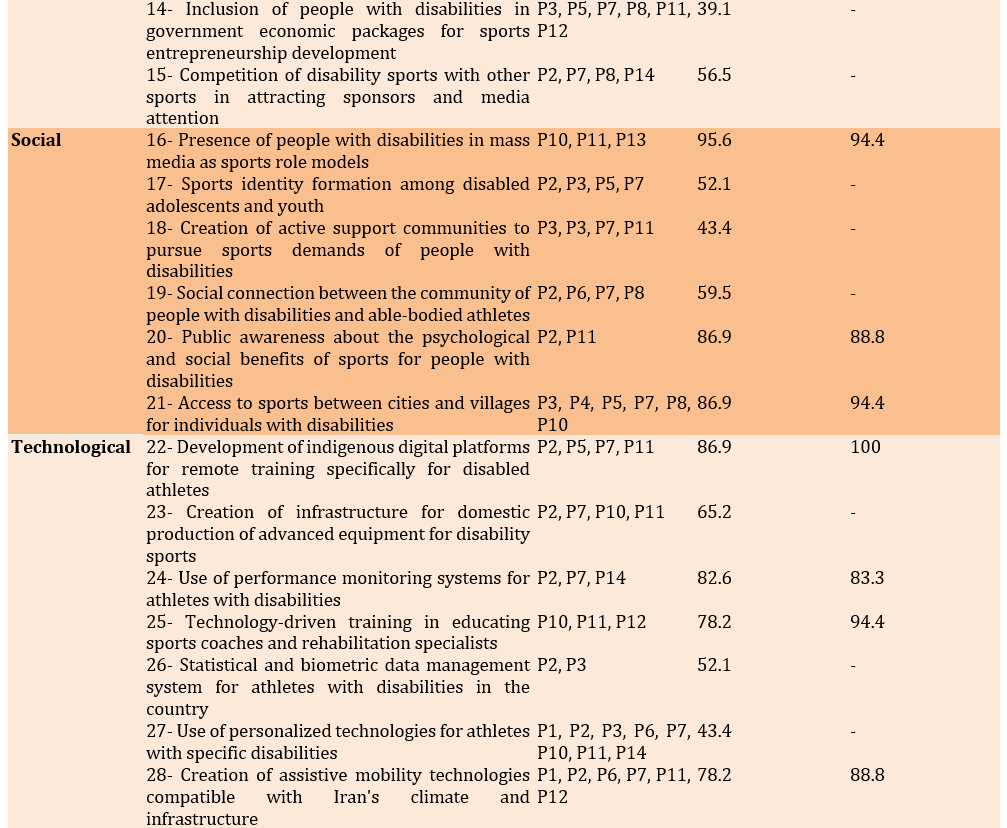

An in-depth literature review and semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. The PESTEL framework, covering political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal domains, was applied to categorize drivers of change. Drivers that achieved a consensus percentage above 70% [27], along with their statistical summaries on a 5-point Likert scale, were provided to the experts in the third Delphi round.

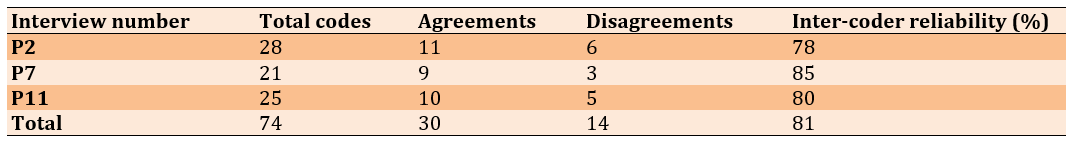

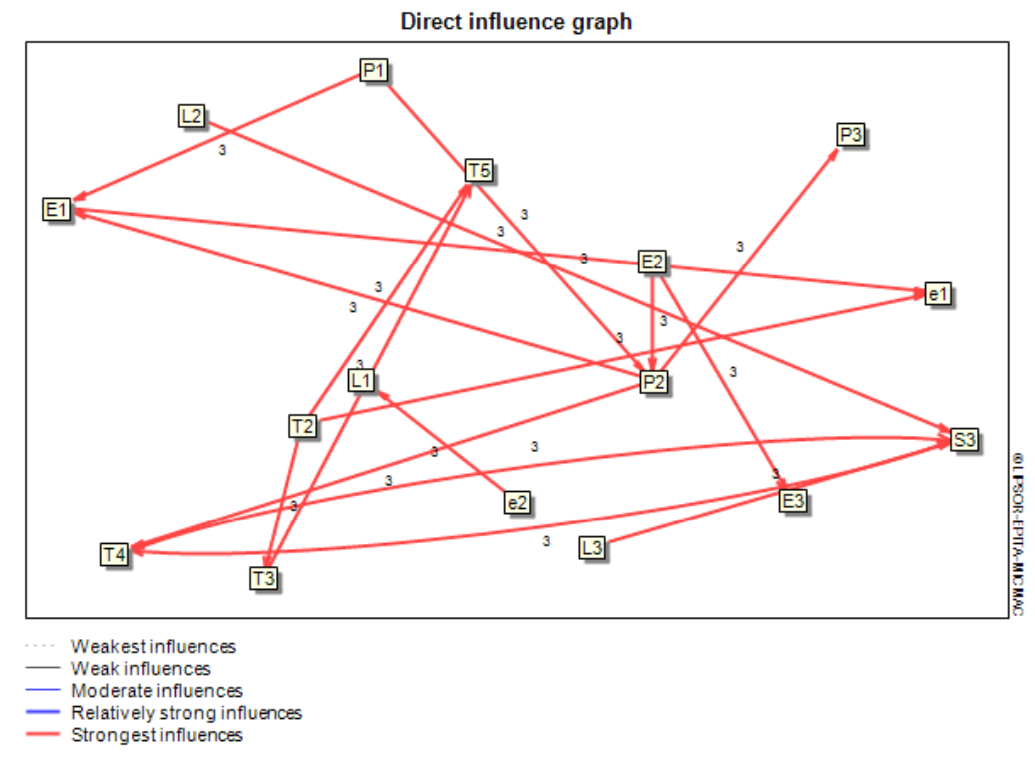

Triangulation of the literature review and interviews was employed to strengthen credibility. Member checking was performed by sharing preliminary findings with participants for confirmation. Transferability was ensured by providing detailed descriptions of the research context. Confirmability was established through a documented audit trail and external review. Inter-coder reliability was calculated at 81%, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 60% (Table 1).

Table 1. Inter-coder reliability

Data collection

In the first Delphi round, open-ended interviews explored participants’ views on the main drivers shaping the future of disability sport in Iran. Follow-up questions probed for additional detail. Identified drivers were compiled into a structured questionnaire for the second round, where participants rated the importance and influence of each item. Drivers with less than 70% consensus were excluded. The third round provided the revised list for final validation, resulting in 21 agreed-upon drivers.

Statistical analysis

Cross-impact analysis was conducted using MICMAC software to assess the relationships among drivers. The scenario planning stage applied the cross-impact matrix to identify possible future configurations, with Scenario Wizard software generating the final set of probable scenarios.

Findings

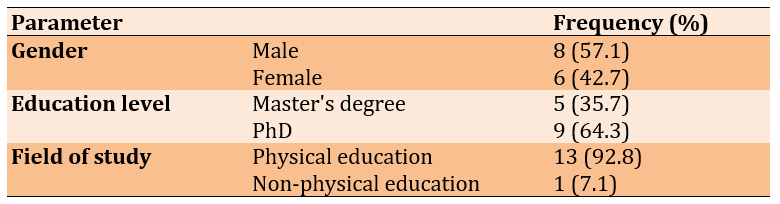

To answer the main research question, “What driving forces can shape the future of sports for PwD in Iran?”, a review of existing research in the field of disability sports and foresight in sports was conducted. The lowest experience level was 7 years, and the highest was 25 years and the lowest age was 30 years, and the highest age was 50 years. Additionally, the Delphi method was used to refine and determine the importance of these driving forces (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of demographic characteristics of Delphi group experts

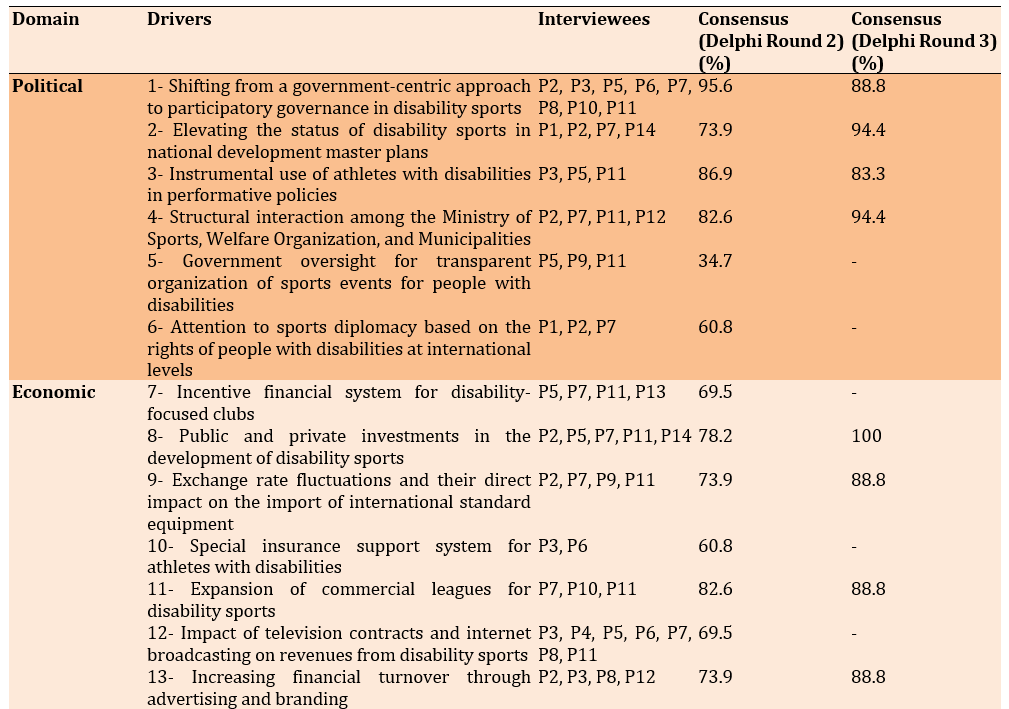

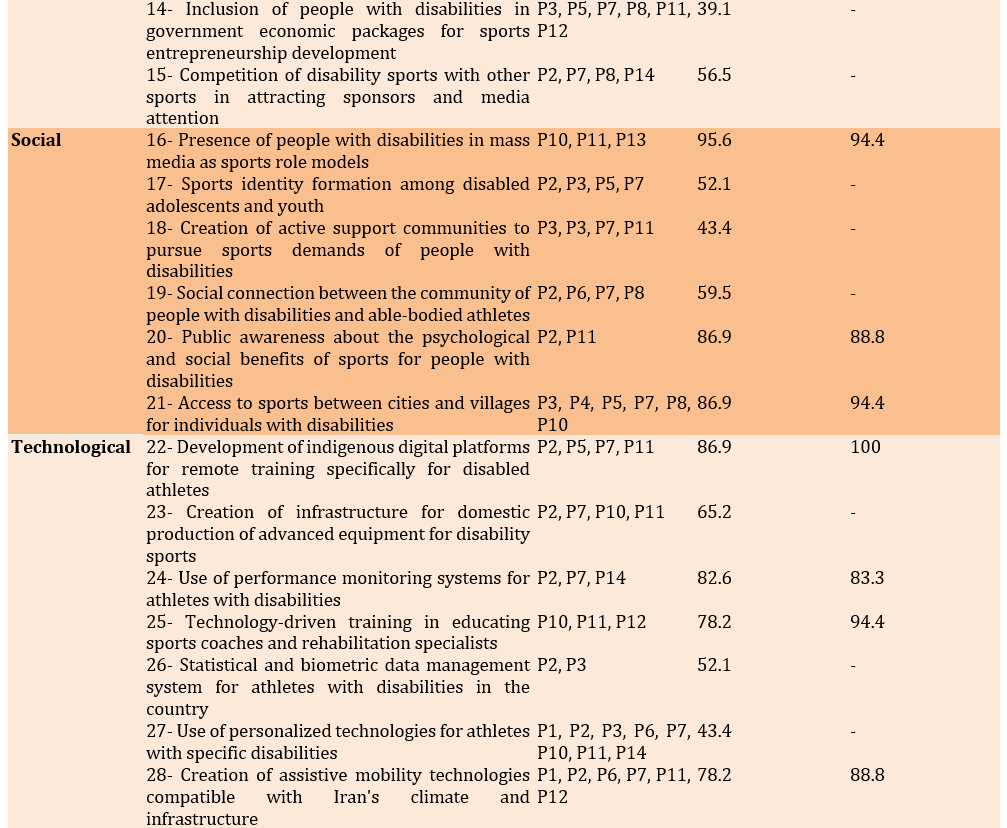

After the literature review, the Delphi technique was used to finalize the list of drivers for disability sports. In the first Delphi round, 14 semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts in the field of disability sports, which helped complete the list of future drivers for disability sports in Iran. In the second round, a semi-structured questionnaire was distributed to the Delphi group to determine the importance of 41 future drivers of disability sports using a 5-point Likert scale. Drivers that received a consensus below 70% from the Delphi group in the second round were marked in red. Experts were consulted at least twice on each component, allowing them to review their opinions at least once, considering the responses of the entire group presented in statistical summaries. Therefore, all drivers that achieved a consensus percentage above 70%, along with their statistical summaries on a 5-point Likert scale, were provided to the experts in the third Delphi round (Table 3).

Table 3. Future drivers of sports for people with disabilities in Iran

Analysis of driving forces and interactions

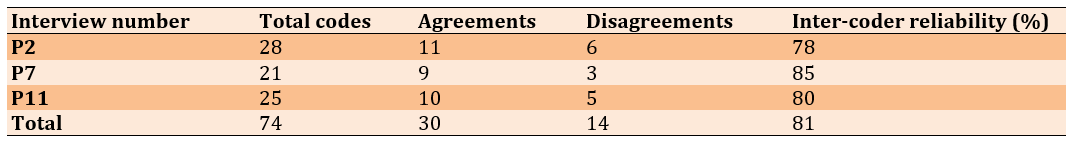

After identifying 21 influential driving forces for the development of sports for PwD, a 21x21 matrix was designed. This matrix was provided to the expert group to determine the relationships and interactions among these drivers using a scale from 0 to 3, where 0 indicated no influence, 1 represented weak influence, 2 signified moderate influence, 3 denoted strong influence, and P indicated potential influence. This process clarified the extent to which each driver influenced others and, conversely, how much each was influenced. The questionnaire results were then analyzed using MICMAC software.

The overall structure of the cross-impact matrix. The matrix had a size of 21 and was processed in two iterations. The distribution of values included 257 zeros, 64 ones, 50 twos, and 60 threes. In addition, 10 potential influences (P) were recorded. Altogether, the matrix contained 184 active entries, resulting in a fill rate of 41.72%.

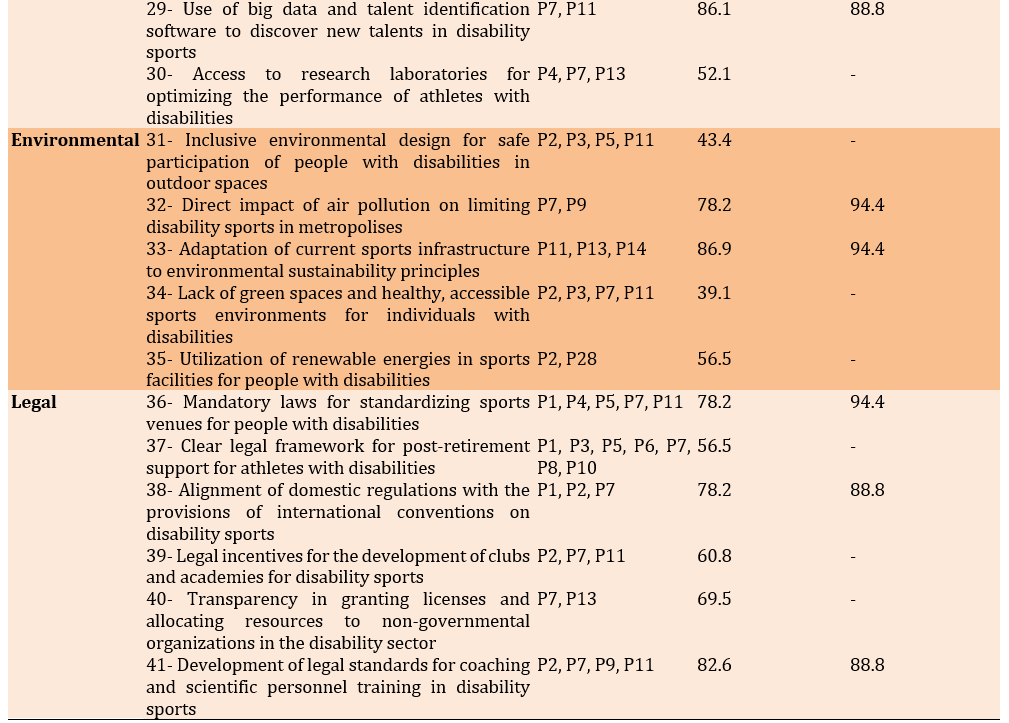

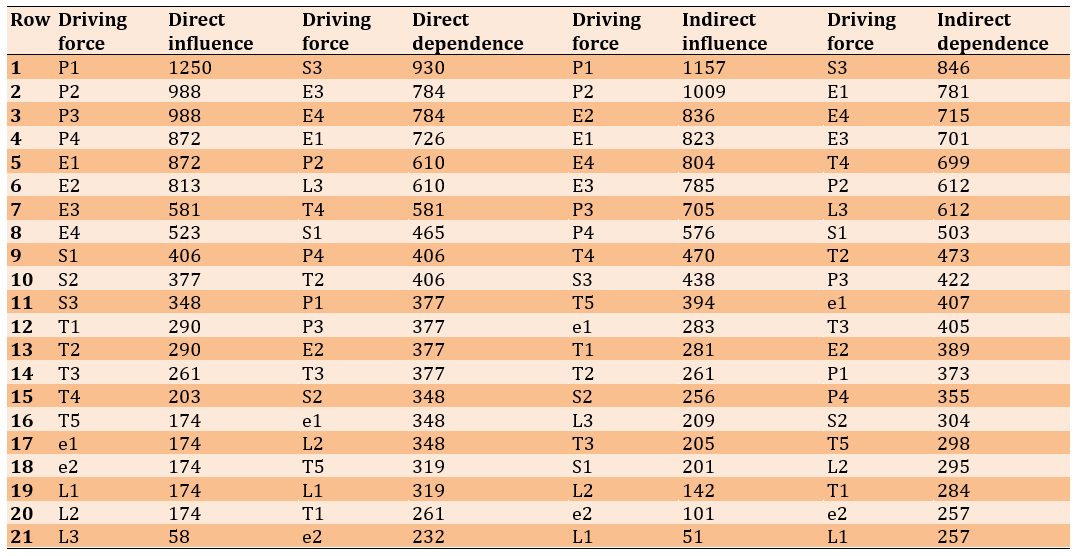

The MICMAC software processes the input data and separates it into two flows and two matrices: the direct influence matrix (DIM) and the indirect influence matrix (IIM) (Table 4).

Table 4. Prioritization of direct and indirect influences of driving forces

MICMAC software results and system stability analysis

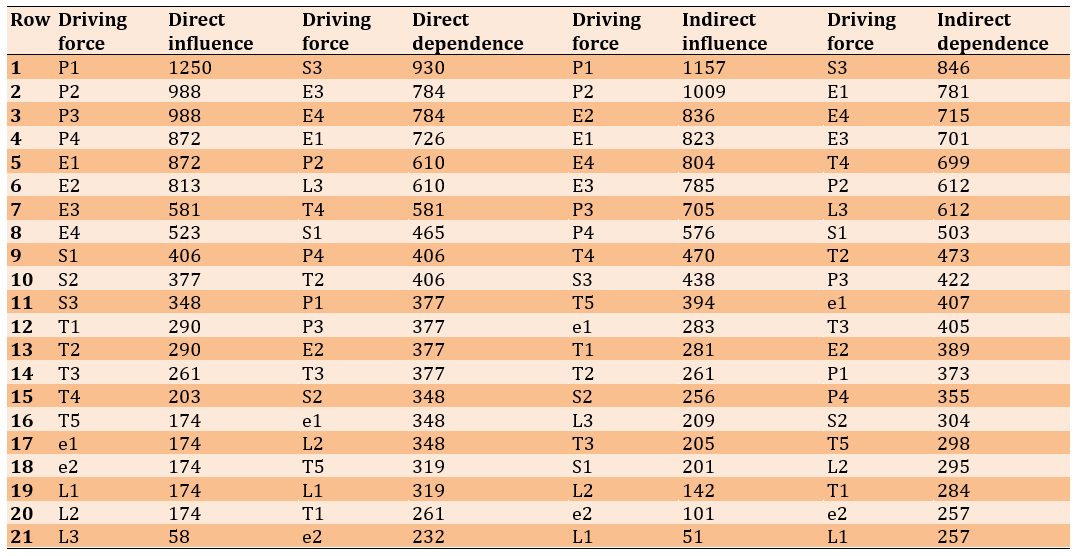

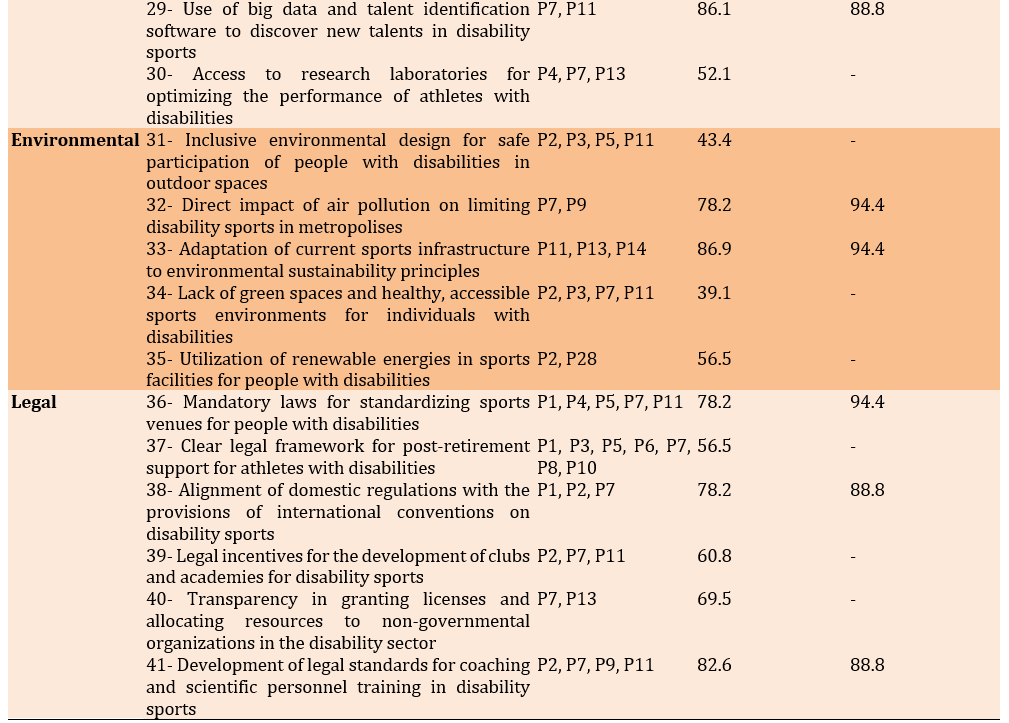

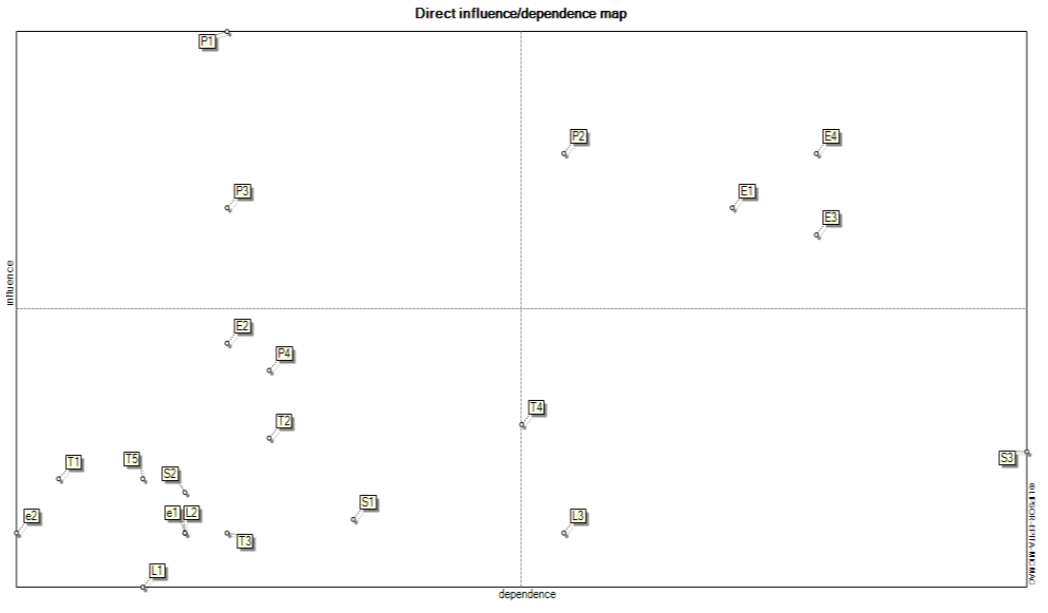

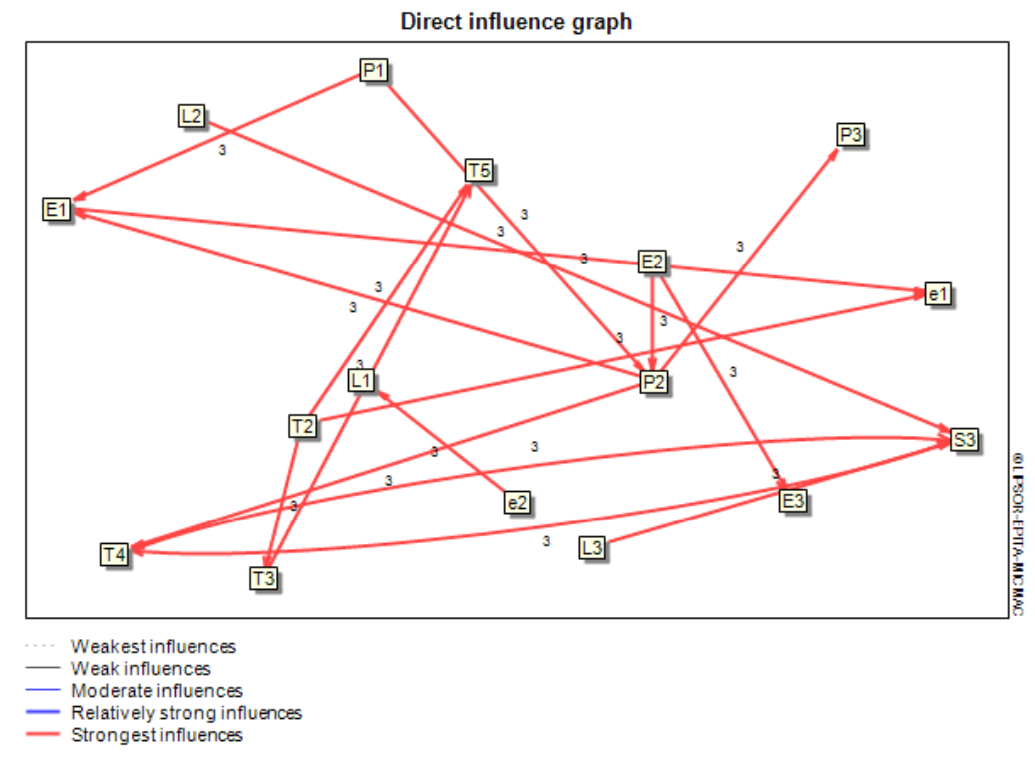

The stability or instability of the system was analyzed using the direct influence and dependence plane. According to the MICMAC output and expert opinions, the future of sports for PwD is predicted to be somewhat unstable, indicating a potential for current conditions to change. Considering the findings from the direct influence matrix (DIM) map, the driving forces for sports for PwD were categorized into four quadrants (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Influence and dependence status of drivers in the direct influence matrix (DIM)

Figure 2. Direct influence graph of drivers in the direct influence matrix (DIM).

The drivers of sports for people with disabilities (PwD) in Iran are categorized into four types based on their position. Zone one drivers, classified as bipolar, include P2, E1, E3, and E4. Zone two drivers, considered influential, consist of P1 and P3. Zone three drivers, identified as independent, encompass P4, T1, T2, T3, T5, E1, E2, S1, S2, L1, and L2. Finally, Zone four drivers, categorized as dependent, include T4, L3, and S3.

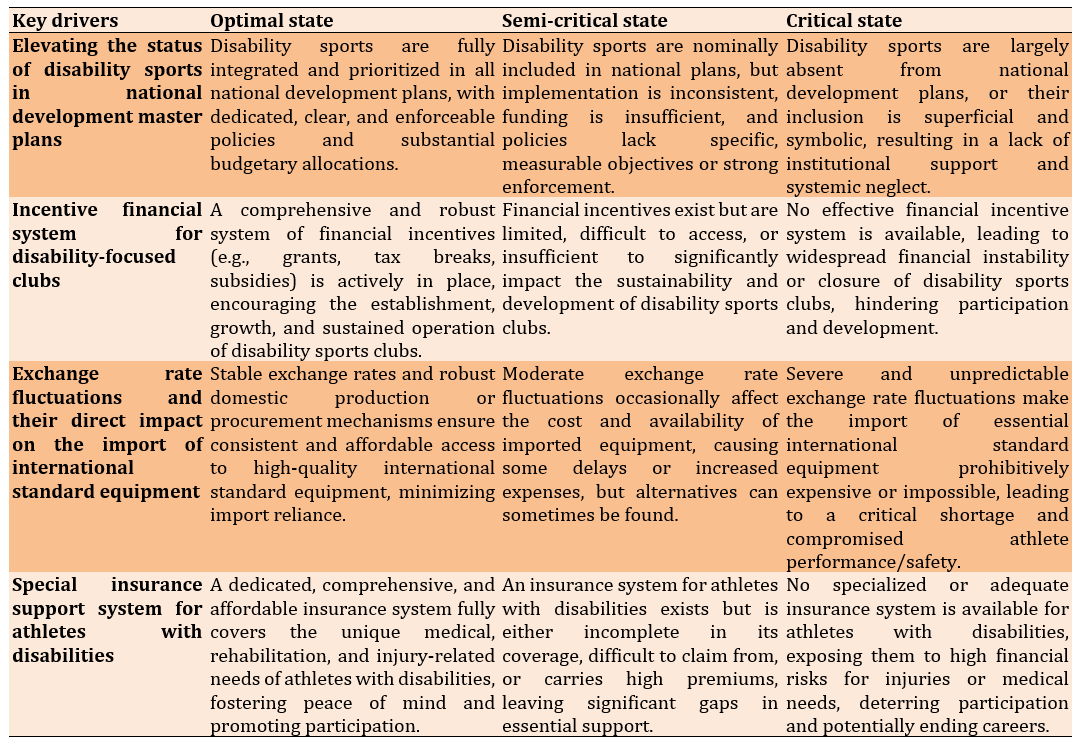

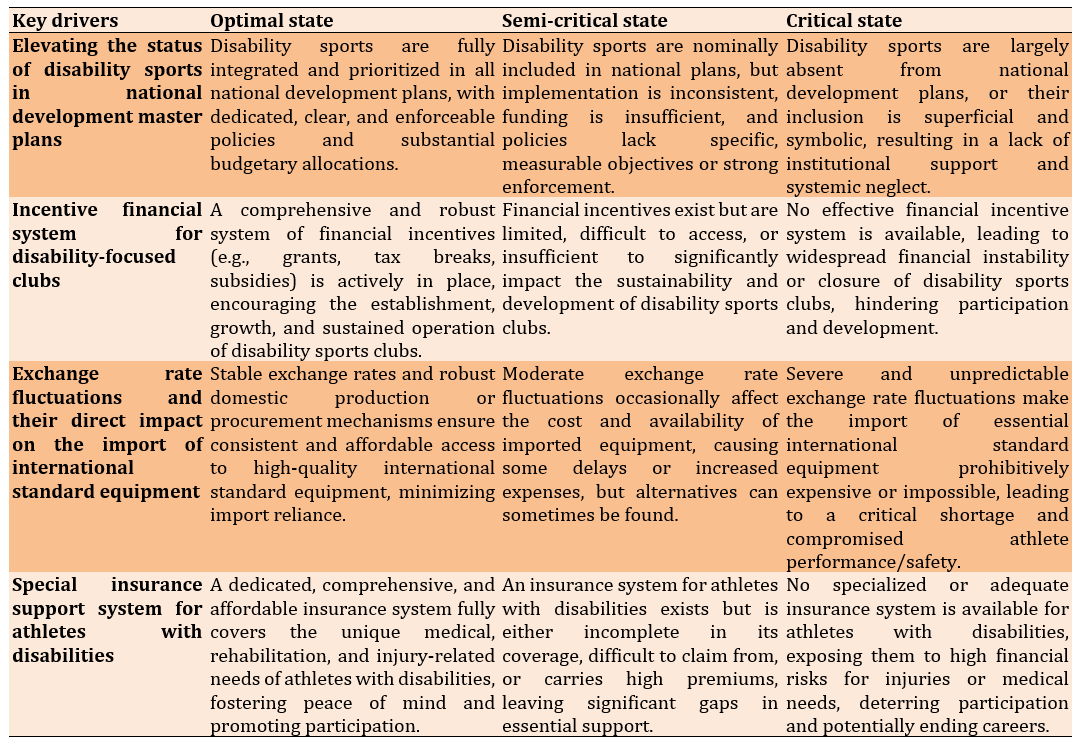

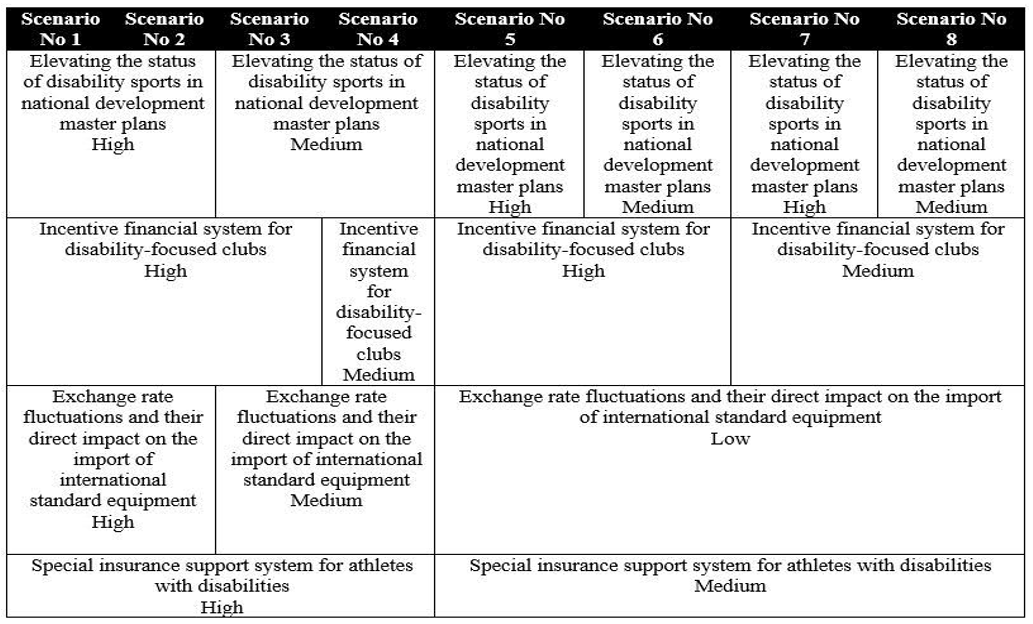

Therefore, the four drivers—“Elevating the status of disability sports in national development master plans,” “Incentive financial system for disability-focused clubs,” “Exchange rate fluctuations and their direct impact on the import of international standard equipment,” and “Special insurance support system for athletes with disabilities”—were considered key drivers.

The probable states encompass a spectrum from desirable to critical conditions, with three states considered for each driver (Table 5).

Table 5. Probable states of key drivers

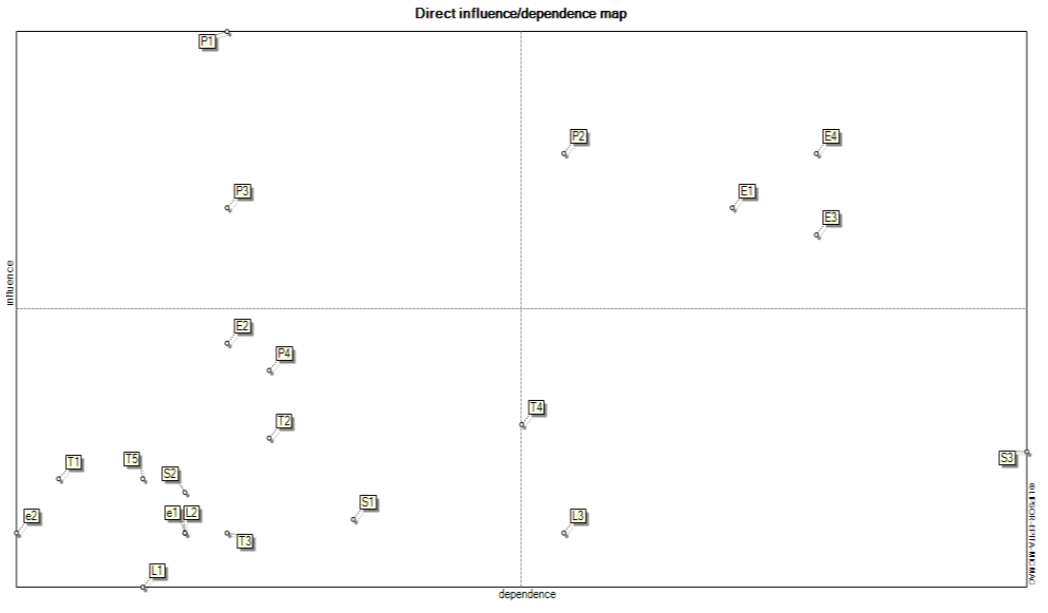

Based on the probable states for the four key drivers concerning the future of PwD, a total of 12 scenarios were designed, ranging from optimal to critical conditions. Scenario Wizard software then created a 12x12 matrix to evaluate the inter-impact of these different states. This matrix was presented to the Delphi group, where the experts were required to specify what effect the occurrence of each of the 12 states would have on the occurrence or non-occurrence of the other states. The questionnaire was scored on a range from positive 3 to negative 3, representing a continuum from reinforcing to weakening characteristics.

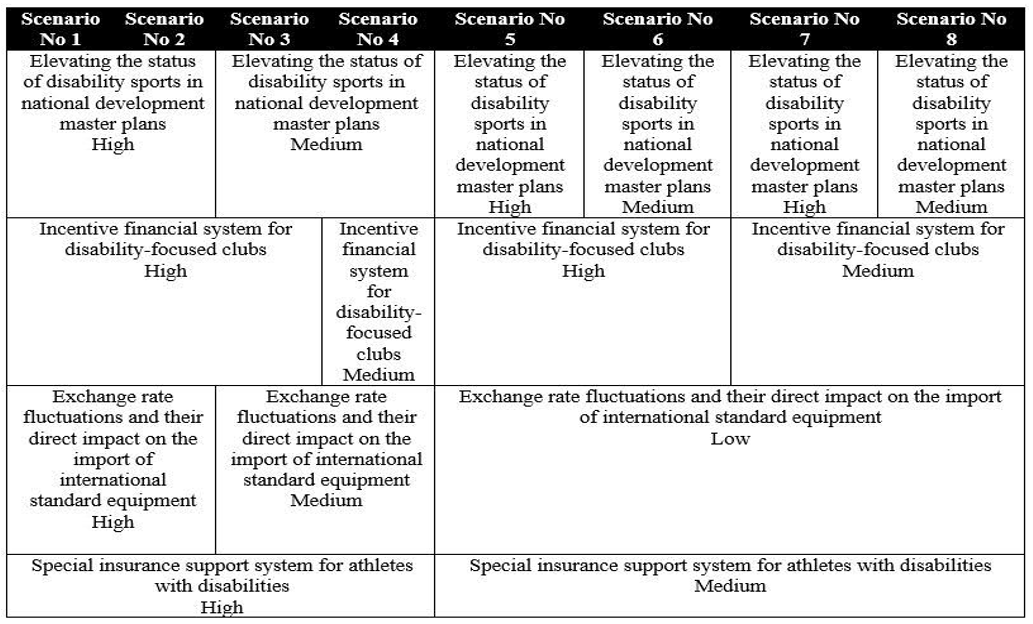

Eight high-scoring scenarios with a greater likelihood of occurrence were identified for the future of disability sports in Iran (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Compatible future scenarios for disability sport in Iran

The foresight analysis of disability sport in Iran outlined eight possible future scenarios, ranging from optimal conditions to critical decline. In the most favorable scenario, all key drivers performed at their highest potential. Disability sport was fully institutionalized within national health and development agendas, stable and coordinated financial support is in place, currency fluctuations had no negative impact on the import of standard equipment, and specialized insurance provided comprehensive medical, rehabilitation, and injury coverage for athletes.

In a relatively optimistic outlook, three of the main drivers remained strong, but currency volatility moderately affected the supply of essential equipment, creating some barriers to access. The third scenario reflected partial progress, where certain support structures, such as financial incentives and insurance, remained robust; however, currency instability and weak policymaking disrupted program continuity and coherence.

In the fourth scenario, most drivers were at a moderate level, with only insurance rated high, while economic and operational challenges hindered sustained health and participation outcomes. The fifth scenario showed strong political and financial backing, but inadequate infrastructure and currency-related constraints limited the delivery of appropriate services and equipment.

In the sixth scenario, a severe shortage of equipment and institutional weakness created major obstacles, with only financial support showing relative stability. The seventh scenario combined high political commitment with operational barriers, including limited funding, inadequate insurance, and restricted access to equipment.

The most adverse scenario reflected complete stagnation and structural decline, where all key drivers were at moderate or low levels. Severe economic instability, insufficient financial support, poor infrastructure, and inadequate insurance collectively threatened the continuity of sport and rehabilitation services. Thus, the future of disability sport in Iran depends on aligning health policy, economic stability, infrastructure development, and comprehensive insurance coverage.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify strategic drivers shaping the future of disability sport in Iran by 2034. It provides one of the first foresight-based examinations of the strategic determinants shaping disability sport in a Global South context, specifically within Iran. By employing a structured multi-round Delphi methodology in conjunction with cross-impact analysis and scenario planning, the research advances beyond descriptive inventories of barriers or facilitators and instead interrogates the dynamic, interdependent relationships among political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal drivers. Such an approach is particularly relevant to the medical sciences, where complex systems thinking is increasingly recognized as essential for addressing multifactorial determinants of health, equity, and social participation.

The trajectory of disability sport was embedded within broader determinants of public health. The alignment of political commitment across key governance institutions—most notably the Ministry of Sport, the Welfare Organization, and municipal agencies—emerged as a fundamental enabling condition for policy coherence, resource stability, and program continuity. This governance integration is consistent with evidence in health policy research, where fragmented institutional frameworks have been shown to limit the scalability and sustainability of health-promoting interventions for vulnerable populations [28, 29].

Economic stability likewise emerged as a critical determinant, with currency volatility and the absence of comprehensive insurance frameworks constraining access to standardized equipment and long-term athlete welfare. These findings parallel global public health evidence linking financial resilience and predictable funding streams to the sustained accessibility of essential health and rehabilitation services for PwD.

Technological innovation was identified as both a transformative catalyst and a potential amplifier of inequality. Adaptive sports equipment, digital training platforms, and AI-enabled performance monitoring align closely with the growing emphasis on technology-assisted rehabilitation and personalized health promotion. However, without intentional strategies to ensure equitable access, these advancements risk reinforcing existing disparities—a challenge similarly observed in the digital health domain [30]. Notably, high-consensus drivers in this study, such as the development of indigenous digital training applications and the application of big data for talent identification, offer scalable pathways for integrating technological equity into national sport and health agendas.

The environmental dimension, often marginalized in sport policy discourse, assumes heightened relevance when considered through a health equity lens. Exposure to urban air pollution, combined with limited availability of accessible green spaces, not only exacerbates chronic disease risk but also symbolically and physically excludes PwD from community participation. This aligns with the concept of spatial justice in public health, wherein urban design and environmental planning are integral to equitable health outcomes [31].

From a legal standpoint, the absence of enforceable accessibility standards for sport facilities, structured certification pathways for disability sport coaches, and the incorporation of rights-based international frameworks (e.g., UNCRPD) into domestic policy reflect structural gaps in the enabling environment for health-promoting sport participation. The proposed legal drivers identified here, such as post-retirement protections for athletes with disabilities and transparent NGO accreditation, demonstrate the potential to transition disability sport policy from a welfare-oriented paradigm to an empowerment-focused model.

Overall, advancing disability sport in Iran cannot rely on scattered actions or one-time events. Meaningful and lasting progress demands a unified, multi-sector approach that embeds sport within the core of public health strategy. In this role, sport should be recognized not merely as a recreational option but as a powerful tool for improving health equity, enhancing psychological well-being, and fostering the full social inclusion of PwD within their communities.

This study was designed and conducted with a focus on methodological rigor, expert engagement, and comprehensive data triangulation. While foresight analysis inherently involves exploring multiple possible futures, the scenarios developed here reflect the perspectives of a carefully selected group of national experts in disability sport and health policy. The sampling approach prioritized depth of expertise and sectoral representation rather than statistical generalization, which aligns with the qualitative and exploratory nature of the research. Additionally, the drivers and scenarios identified are intended to serve as a strategic framework that can be further enriched through continued dialogue, stakeholder engagement, and the integration of emerging evidence. These considerations do not diminish the validity or applicability of the findings; rather, they highlight opportunities for future research to build on the present work and expand its scope to additional contexts and participant groups.

Policymakers should establish a national foresight plan that links disability sport with health and development agendas. Such a plan requires investment in infrastructure, equal access to technology, and enforceable legal standards. At the societal level, disability sport must be viewed as a health intervention that reduces chronic disease risk, strengthens mental health, and builds social cohesion. Foresight methods provide decision-makers with a practical tool to anticipate change and design inclusive strategies for one of the most underrepresented groups in public health.

Conclusion

Positioning disability sport as a public health priority in Iran requires strong political commitment, stable financing, access to adaptive technologies, and inclusive environmental design.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their sincere gratitude to all experts who participated in the Delphi rounds and generously shared their knowledge and experiences. Their valuable contributions were instrumental in shaping the outcomes of this foresight study.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Naghizadeh Baghi A (First Author), Main Researcher (50%); Zare Abandansari M (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Pourzabih Sarhamami Kh (Third Author), Introduction Writer (18%); Nobakht F (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (12%)

Funding/Support: This research was financially supported by the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

In the evolving global discourse on health equity and inclusive development, sports participation among persons with disabilities (PwD) is increasingly recognized as a critical dimension of sustainable social policy [1]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 16% of the world’s population lives with some form of disability, a figure that rises significantly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to services and infrastructure remains limited. These populations frequently encounter systemic obstacles that constrain their autonomy, social inclusion, and access to physical and mental health resources [2, 3].

Empirical research consistently shows that PwD engage far less in recreational, physical, and cultural activities than the general population. This disparity is shaped by environmental inaccessibility, social stigmatization, and inadequate policy frameworks [4-6]. In Iran, many PwD remain confined to sedentary lifestyles due to a lack of infrastructure and community engagement, spending their leisure time passively [7, 8]. These patterns are associated with an increased risk of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and cancer [9, 10].

Beyond physical health, inclusive sport plays a vital role in supporting identity development, social participation, and psychological resilience. Participation in structured programs has been linked to greater self-esteem, reduced depression, improved mood, and stronger community integration [11-13]. Adaptive sports, like wheelchair basketball serve as arenas for self-expression and collective belonging [6, 14].

Yet, major obstacles remain. Urban environments in LMICs often lack accessible design, adaptive equipment, and qualified instructors [1, 15]. Policies frequently adopt segregated models, perpetuating exclusion [16, 17]. Despite growing awareness, sports participation among PwD remains hindered by structural and attitudinal barriers, particularly in settings like Iran, where there is an uneven distribution of sports resources [18, 19].

Much of Iran’s recent disability sport policy has focused on short-term initiatives, such as the donation of adaptive equipment or isolated community events [14, 20]. These fragmented interventions rarely reflect the lived experiences of PwD or long-term strategic priorities. In this context, foresight methodology offers a proactive tool for envisioning inclusive futures, identifying drivers of change, and anticipating policy challenges [21, 22].

Despite the existence of studies examining barriers to sports participation [23, 24], few have applied systems-level foresight analysis to the field of disability sport, especially in Iran. The lack of a long-term roadmap hinders national efforts to integrate assistive technologies, train human capital, and align urban planning with inclusion goals [7, 25]. As Iran undergoes demographic shifts and technological changes, reactive and fragmented strategies are no longer sufficient [8, 26].

Although research on disability sport has grown in recent years, much of it remains limited to descriptive analyses or examinations of isolated barriers. Few studies address forward-looking strategies that integrate demographic changes, technological advances, and policy reforms with measurable health outcomes. In Iran, this gap is particularly evident, as initiatives for people with disabilities in sport are still largely short-term and event-focused, rather than embedded in long-term, health-oriented strategic planning. Despite rising public and institutional awareness, the use of foresight methodology to guide disability sport development and its role in promoting physical and mental health remains critically underutilized.

Little attention has been paid to the interconnected structural, economic, and policy drivers that can shape equitable participation and reduce health disparities over the next decade. This study addressed this gap by systematically identifying and analyzing the key factors likely to influence the future of disability sport in Iran by 2034. Using a foresight-based approach, it aimed to guide the creation of proactive, inclusive, and context-specific policies that not only expand access but also position sport as an integral component of national health promotion strategies, empowering people with disabilities to be active participants and decision-makers in shaping their health and well-being.

Instrument and Methods

Study design and sample

The foresight-driven study based on scenario planning methodology employed a theoretical applied design. From the theoretical perspective, it aimed to enrich the academic discourse on disability sport by providing conceptual depth and explanatory insights. From the applied perspective, the findings were intended to form a strategic basis for evidence-based planning to enhance sports participation among PwD in Iran.

Participants were selected from a national pool of experts in disability sport. The group included senior managers and officials from disability-related sport federations, elite coaches, referees, athletes from different disciplines, and university faculty members with expertise in physical education, sport management, or adapted physical activity. Selection criteria included experience in athletic or administrative roles within disability sport and an academic or research background in foresight studies or disability sport development. Due to the absence of an official database, purposive and criterion-based sampling was used. Recruitment continued until theoretical saturation was reached, resulting in 14 participants.

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants. As the research design relied on expert interviews and Delphi rounds with professionals in disability sport, no clinical or medical interventions were conducted. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses, and their right to withdraw at any stage without penalty was explicitly respected.

Study tools

An in-depth literature review and semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. The PESTEL framework, covering political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal domains, was applied to categorize drivers of change. Drivers that achieved a consensus percentage above 70% [27], along with their statistical summaries on a 5-point Likert scale, were provided to the experts in the third Delphi round.

Triangulation of the literature review and interviews was employed to strengthen credibility. Member checking was performed by sharing preliminary findings with participants for confirmation. Transferability was ensured by providing detailed descriptions of the research context. Confirmability was established through a documented audit trail and external review. Inter-coder reliability was calculated at 81%, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 60% (Table 1).

Table 1. Inter-coder reliability

Data collection

In the first Delphi round, open-ended interviews explored participants’ views on the main drivers shaping the future of disability sport in Iran. Follow-up questions probed for additional detail. Identified drivers were compiled into a structured questionnaire for the second round, where participants rated the importance and influence of each item. Drivers with less than 70% consensus were excluded. The third round provided the revised list for final validation, resulting in 21 agreed-upon drivers.

Statistical analysis

Cross-impact analysis was conducted using MICMAC software to assess the relationships among drivers. The scenario planning stage applied the cross-impact matrix to identify possible future configurations, with Scenario Wizard software generating the final set of probable scenarios.

Findings

To answer the main research question, “What driving forces can shape the future of sports for PwD in Iran?”, a review of existing research in the field of disability sports and foresight in sports was conducted. The lowest experience level was 7 years, and the highest was 25 years and the lowest age was 30 years, and the highest age was 50 years. Additionally, the Delphi method was used to refine and determine the importance of these driving forces (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of demographic characteristics of Delphi group experts

After the literature review, the Delphi technique was used to finalize the list of drivers for disability sports. In the first Delphi round, 14 semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts in the field of disability sports, which helped complete the list of future drivers for disability sports in Iran. In the second round, a semi-structured questionnaire was distributed to the Delphi group to determine the importance of 41 future drivers of disability sports using a 5-point Likert scale. Drivers that received a consensus below 70% from the Delphi group in the second round were marked in red. Experts were consulted at least twice on each component, allowing them to review their opinions at least once, considering the responses of the entire group presented in statistical summaries. Therefore, all drivers that achieved a consensus percentage above 70%, along with their statistical summaries on a 5-point Likert scale, were provided to the experts in the third Delphi round (Table 3).

Table 3. Future drivers of sports for people with disabilities in Iran

Analysis of driving forces and interactions

After identifying 21 influential driving forces for the development of sports for PwD, a 21x21 matrix was designed. This matrix was provided to the expert group to determine the relationships and interactions among these drivers using a scale from 0 to 3, where 0 indicated no influence, 1 represented weak influence, 2 signified moderate influence, 3 denoted strong influence, and P indicated potential influence. This process clarified the extent to which each driver influenced others and, conversely, how much each was influenced. The questionnaire results were then analyzed using MICMAC software.

The overall structure of the cross-impact matrix. The matrix had a size of 21 and was processed in two iterations. The distribution of values included 257 zeros, 64 ones, 50 twos, and 60 threes. In addition, 10 potential influences (P) were recorded. Altogether, the matrix contained 184 active entries, resulting in a fill rate of 41.72%.

The MICMAC software processes the input data and separates it into two flows and two matrices: the direct influence matrix (DIM) and the indirect influence matrix (IIM) (Table 4).

Table 4. Prioritization of direct and indirect influences of driving forces

MICMAC software results and system stability analysis

The stability or instability of the system was analyzed using the direct influence and dependence plane. According to the MICMAC output and expert opinions, the future of sports for PwD is predicted to be somewhat unstable, indicating a potential for current conditions to change. Considering the findings from the direct influence matrix (DIM) map, the driving forces for sports for PwD were categorized into four quadrants (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Influence and dependence status of drivers in the direct influence matrix (DIM)

Figure 2. Direct influence graph of drivers in the direct influence matrix (DIM).

The drivers of sports for people with disabilities (PwD) in Iran are categorized into four types based on their position. Zone one drivers, classified as bipolar, include P2, E1, E3, and E4. Zone two drivers, considered influential, consist of P1 and P3. Zone three drivers, identified as independent, encompass P4, T1, T2, T3, T5, E1, E2, S1, S2, L1, and L2. Finally, Zone four drivers, categorized as dependent, include T4, L3, and S3.

Therefore, the four drivers—“Elevating the status of disability sports in national development master plans,” “Incentive financial system for disability-focused clubs,” “Exchange rate fluctuations and their direct impact on the import of international standard equipment,” and “Special insurance support system for athletes with disabilities”—were considered key drivers.

The probable states encompass a spectrum from desirable to critical conditions, with three states considered for each driver (Table 5).

Table 5. Probable states of key drivers

Based on the probable states for the four key drivers concerning the future of PwD, a total of 12 scenarios were designed, ranging from optimal to critical conditions. Scenario Wizard software then created a 12x12 matrix to evaluate the inter-impact of these different states. This matrix was presented to the Delphi group, where the experts were required to specify what effect the occurrence of each of the 12 states would have on the occurrence or non-occurrence of the other states. The questionnaire was scored on a range from positive 3 to negative 3, representing a continuum from reinforcing to weakening characteristics.

Eight high-scoring scenarios with a greater likelihood of occurrence were identified for the future of disability sports in Iran (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Compatible future scenarios for disability sport in Iran

The foresight analysis of disability sport in Iran outlined eight possible future scenarios, ranging from optimal conditions to critical decline. In the most favorable scenario, all key drivers performed at their highest potential. Disability sport was fully institutionalized within national health and development agendas, stable and coordinated financial support is in place, currency fluctuations had no negative impact on the import of standard equipment, and specialized insurance provided comprehensive medical, rehabilitation, and injury coverage for athletes.

In a relatively optimistic outlook, three of the main drivers remained strong, but currency volatility moderately affected the supply of essential equipment, creating some barriers to access. The third scenario reflected partial progress, where certain support structures, such as financial incentives and insurance, remained robust; however, currency instability and weak policymaking disrupted program continuity and coherence.

In the fourth scenario, most drivers were at a moderate level, with only insurance rated high, while economic and operational challenges hindered sustained health and participation outcomes. The fifth scenario showed strong political and financial backing, but inadequate infrastructure and currency-related constraints limited the delivery of appropriate services and equipment.

In the sixth scenario, a severe shortage of equipment and institutional weakness created major obstacles, with only financial support showing relative stability. The seventh scenario combined high political commitment with operational barriers, including limited funding, inadequate insurance, and restricted access to equipment.

The most adverse scenario reflected complete stagnation and structural decline, where all key drivers were at moderate or low levels. Severe economic instability, insufficient financial support, poor infrastructure, and inadequate insurance collectively threatened the continuity of sport and rehabilitation services. Thus, the future of disability sport in Iran depends on aligning health policy, economic stability, infrastructure development, and comprehensive insurance coverage.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify strategic drivers shaping the future of disability sport in Iran by 2034. It provides one of the first foresight-based examinations of the strategic determinants shaping disability sport in a Global South context, specifically within Iran. By employing a structured multi-round Delphi methodology in conjunction with cross-impact analysis and scenario planning, the research advances beyond descriptive inventories of barriers or facilitators and instead interrogates the dynamic, interdependent relationships among political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal drivers. Such an approach is particularly relevant to the medical sciences, where complex systems thinking is increasingly recognized as essential for addressing multifactorial determinants of health, equity, and social participation.

The trajectory of disability sport was embedded within broader determinants of public health. The alignment of political commitment across key governance institutions—most notably the Ministry of Sport, the Welfare Organization, and municipal agencies—emerged as a fundamental enabling condition for policy coherence, resource stability, and program continuity. This governance integration is consistent with evidence in health policy research, where fragmented institutional frameworks have been shown to limit the scalability and sustainability of health-promoting interventions for vulnerable populations [28, 29].

Economic stability likewise emerged as a critical determinant, with currency volatility and the absence of comprehensive insurance frameworks constraining access to standardized equipment and long-term athlete welfare. These findings parallel global public health evidence linking financial resilience and predictable funding streams to the sustained accessibility of essential health and rehabilitation services for PwD.

Technological innovation was identified as both a transformative catalyst and a potential amplifier of inequality. Adaptive sports equipment, digital training platforms, and AI-enabled performance monitoring align closely with the growing emphasis on technology-assisted rehabilitation and personalized health promotion. However, without intentional strategies to ensure equitable access, these advancements risk reinforcing existing disparities—a challenge similarly observed in the digital health domain [30]. Notably, high-consensus drivers in this study, such as the development of indigenous digital training applications and the application of big data for talent identification, offer scalable pathways for integrating technological equity into national sport and health agendas.

The environmental dimension, often marginalized in sport policy discourse, assumes heightened relevance when considered through a health equity lens. Exposure to urban air pollution, combined with limited availability of accessible green spaces, not only exacerbates chronic disease risk but also symbolically and physically excludes PwD from community participation. This aligns with the concept of spatial justice in public health, wherein urban design and environmental planning are integral to equitable health outcomes [31].

From a legal standpoint, the absence of enforceable accessibility standards for sport facilities, structured certification pathways for disability sport coaches, and the incorporation of rights-based international frameworks (e.g., UNCRPD) into domestic policy reflect structural gaps in the enabling environment for health-promoting sport participation. The proposed legal drivers identified here, such as post-retirement protections for athletes with disabilities and transparent NGO accreditation, demonstrate the potential to transition disability sport policy from a welfare-oriented paradigm to an empowerment-focused model.

Overall, advancing disability sport in Iran cannot rely on scattered actions or one-time events. Meaningful and lasting progress demands a unified, multi-sector approach that embeds sport within the core of public health strategy. In this role, sport should be recognized not merely as a recreational option but as a powerful tool for improving health equity, enhancing psychological well-being, and fostering the full social inclusion of PwD within their communities.

This study was designed and conducted with a focus on methodological rigor, expert engagement, and comprehensive data triangulation. While foresight analysis inherently involves exploring multiple possible futures, the scenarios developed here reflect the perspectives of a carefully selected group of national experts in disability sport and health policy. The sampling approach prioritized depth of expertise and sectoral representation rather than statistical generalization, which aligns with the qualitative and exploratory nature of the research. Additionally, the drivers and scenarios identified are intended to serve as a strategic framework that can be further enriched through continued dialogue, stakeholder engagement, and the integration of emerging evidence. These considerations do not diminish the validity or applicability of the findings; rather, they highlight opportunities for future research to build on the present work and expand its scope to additional contexts and participant groups.

Policymakers should establish a national foresight plan that links disability sport with health and development agendas. Such a plan requires investment in infrastructure, equal access to technology, and enforceable legal standards. At the societal level, disability sport must be viewed as a health intervention that reduces chronic disease risk, strengthens mental health, and builds social cohesion. Foresight methods provide decision-makers with a practical tool to anticipate change and design inclusive strategies for one of the most underrepresented groups in public health.

Conclusion

Positioning disability sport as a public health priority in Iran requires strong political commitment, stable financing, access to adaptive technologies, and inclusive environmental design.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their sincere gratitude to all experts who participated in the Delphi rounds and generously shared their knowledge and experiences. Their valuable contributions were instrumental in shaping the outcomes of this foresight study.

Ethical Permissions: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Naghizadeh Baghi A (First Author), Main Researcher (50%); Zare Abandansari M (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Pourzabih Sarhamami Kh (Third Author), Introduction Writer (18%); Nobakht F (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (12%)

Funding/Support: This research was financially supported by the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

Keywords:

References

1. Kurniawan A, Rizky Samudro B. Optimizing social and economic inclusion through adaptive sports programs for persons with disabilities: A pathway to achieving SDGs. Int J Curr Sci Res Rev. 2024;7(5):3066-72. [Link] [DOI:10.47191/ijcsrr/V7-i5-67]

2. Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB, Dekker R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(6):871-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/sms.12218]

3. Yazicioglu K, Yavuz F, Goktepe AS, Tan AK. Influence of adapted sports on quality of life and life satisfaction in sport participants and non-sport participants with physical disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2012;5(4):249-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.05.003]

4. Tweedy SM, Vanlandewijck YC. International paralympic committee position stand background and scientific principles of classification in paralympic sport. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(4):259-69. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bjsm.2009.065060]

5. Martin JJ. Benefits and barriers to physical activity for individuals with disabilities: A social-relational model of disability perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(24):2030-7. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2013.802377]

6. Rimmer JH, Rowland JL, Yamaki K. Obesity and secondary conditions in adolescents with disabilities: Addressing the needs of an underserved population. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(3):224-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.005]

7. DePauw KP, Gavron SJ. Disability sport. 2nd ed. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2005. [Link] [DOI:10.5040/9781492596226]

8. Parnes P, Cameron D, Christie N, Cockburn L, Hashemi G, Yoshida K. Disability in low-income countries: Issues and implications. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(14):1170-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09638280902773778]

9. Darcy S, Dowse L. In search of a level playing field: The constraints and benefits of sport participation for people with intellectual disability. Disabil Soc. 2013;28(3):393-407. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09687599.2012.714258]

10. Legg D, Gilbert K. Paralympic legacies. Champaign: Common Ground Publishing; 2011. [Link] [DOI:10.18848/978-1-86335-897-2/CGP]

11. Thomas N, Smith A. Disability, sport and society: An introduction. London: Routledge; 2008. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9780203099360]

12. Brittain I. The paralympic games explained. London: Routledge; 2010. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9780203885567]

13. Howe PD, Silva CF. The fiddle of using the paralympic games as a vehicle for expanding [dis]ability sport participation. Sport Soc. 2018;21(1):125-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17430437.2016.1225885]

14. Misener L, Darcy S, Legg D, Gilbert K. Beyond olympic legacy: Understanding paralympic legacy through a thematic analysis. J Sport Manag. 2013;27(4):329-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/jsm.27.4.329]

15. Steadward RD, Peterson C. Paralympics: Where heroes come. Paralympian. 1997;1(1):6-9. [Link]

16. Blanco-Ayala A, Galvaan R, Fernández-Gavira J. Physical activity and sport in acculturation processes in immigrant women: A systematic review. Societies. 2025;15(5):1-23. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/soc15050117]

17. Edwards S. Accessibility of resource-constrained urban communities for female wheelchair users in the South African context [dissertation]. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand; 2022. [Link]

18. Weston MA. The international right to sport for people with disabilities. Marquette Sports Law Rev. 2017;28:1. [Link]

19. Isidoro-Cabanas E, Soto-Rodriguez FJ, Morales-Rodriguez FM, Perez-Marmol JM. Benefits of adaptive sport on physical and mental quality of life in people with physical disabilities: a meta-analysis. InHealthcare. 2023; 11(18): 2480. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare11182480]

20. Blauwet C, Willick SE. The paralympic movement: Using sports to promote health, disability rights, and social integration for athletes with disabilities. PM R. 2012;4(11):851-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.015]

21. Van De Vliet P. Paralympic athlete health. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(7):458-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091192]

22. Brittain I, Beacom A. Leveraging the London 2012 Paralympic Games: What legacy for disabled people?. Journal of sport and social issues. 2016;40(6):499-521. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0193723516655580]

23. Pitts BG, Shapiro DR. People with disabilities and sport: An exploration of the current literature. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. 2017;21:33-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jhlste.2017.06.003]

24. Shapiro DR, Pitts BG. What little do we know: Content analysis of disability sport in sport management literature. J Sport Manag. 2014;28(6):657-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/JSM.2013-0258]

25. Aitchison CC. Marking difference or making a difference: Constructing places, policies and knowledge of inclusion, exclusion and social justice in leisure, sport and tourism. InThe Critical Turn in Tourism Studies. Routledge. 2007: 77-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-08-045098-8.50010-6]

26. Legg D, Steadward RD. The paralympic games and 60 years of change (1948-2008): Unification and restructuring from a disability and medical model to sport-based competition. Sport Soc. 2011;14(9):1099-115. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17430437.2011.614767]

27. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x]

28. Ginis KA, van der Ploeg HP, Foster C, Lai B, McBride CB, Ng K, et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: a global perspective. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):443-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01164-8]

29. Misener L, Darcy S. Managing disability sport: From athletes with disabilities to inclusive organisational perspectives. Sport Manag Rev. 2014;17(1):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.smr.2013.12.003]

30. Shen Y, Zhang X, Zhao J. Understanding the usage of dockless bike sharing in Singapore. Int J Sustain Transport. 2018;12(9):686-700. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15568318.2018.1429696]

31. Heylighen A, Van der Linden V, Van Steenwinkel I. Ten questions concerning inclusive design of the built environment. Build Environ. 2017;114:507-17. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.12.008]