Volume 17, Issue 3 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(3): 261-267 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: The study followed the ethical guidelines established by the Institutional Scientific Research Board

History

Received: 2025/05/21 | Accepted: 2025/07/6 | Published: 2025/07/19

Received: 2025/05/21 | Accepted: 2025/07/6 | Published: 2025/07/19

How to cite this article

Dhanusia S, Bai P, Sahal M, Suganthirababu P, Jayaraj V, Kumar P et al . Effectiveness of Whole-Body Vibrator and Inclined Treadmill in Balance Improvement in Patients with Diabetic Neuropathy. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (3) :261-267

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1636-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1636-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

S. Dhanusia *1, P. Bai1, M. Sahal1, P. Suganthirababu1, V. Jayaraj1, P. Kumar1, V. Srinivasan1

1- Saveetha College of Physiotherapy, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai, India

Full-Text (HTML) (58 Views)

Introduction

Diabetes is a disease that involves the dysfunctional release of insulin, which causes blood sugar levels to rise and poses risks for heart attacks, high blood pressure, kidney failure, and death. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the number of diagnosed individuals with diabetes will increase from 138 million to 202 million by 2035 [1, 2]. Diabetic neuropathy is a nervous system manifestation of diabetes mellitus. It occurs because high blood sugar levels damage small blood vessels over time; this complication can harm the peripheral nerve fibers and impair the function of the peripheral nervous system [3, 4]. Diabetic neuropathies encompass a broad range of disorders characterized by various neurological impairments. They are among the most frequent and serious long-term complications of diabetes, significantly contributing to illness and mortality. This condition can develop in individuals with any form of diabetes, including both insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent types [5]. Neuropathic manifestations are generally classified as either somatic or autonomic. Among the earliest and most common symptoms of diabetic neuropathy are paraesthesia, tingling, or prickling sensations in the legs and feet. As the condition advances, these symptoms often progress to numbness caused by sensory nerve damage, eventually resulting in a reduced or complete loss of touch, pain, temperature, vibration, and proprioception [6-9].

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) can influence balance as it affects the body’s capacity to detect and react to shifts in position. Consequently, individuals have difficulty maintaining a stable center of gravity, especially when standing or walking. This results in reduced feedback and an impaired motor response, making it more challenging to make postural adjustments, which can lead to an increased risk of falls and instability [10]. The prevalence of balance impairment increases with the duration of diabetes and poorer glycemic control. Research suggests that about 16% of those with diabetes experience balance problems, rising to between 30% and 50% as the condition worsens [11, 12]. In addition, damage to sensory nerves caused by diabetic neuropathy can reduce proprioceptive awareness, affecting joint position and limb movement. This may lead to impaired balance and coordination, especially during weight shifts and precise actions [13]. Balance issues in DPN arise from sensory loss, motor dysfunction, proprioceptive impairments, muscle weakness, and alterations in gait [14, 15].

A range of medications is available to manage diabetes, with treatment plans typically tailored to individual needs [16, 17]. Metformin is commonly the first drug of choice; it lowers the production of glucose in the liver and enhances the body’s sensitivity to insulin. Sulfonylureas, such as glipizide, work by stimulating the pancreas to produce increased amounts of insulin. Meanwhile, SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin help control blood sugar levels by promoting the excretion of glucose through urine [18]. Although there are many pharmacological treatment options for diabetes, the literature shows that they are not adequately effective, as diabetes is a multifactorial disorder. For example, sulfonylureas carry a higher risk of heart failure with high-dose monotherapy [19]. Traditional rehabilitation methods for balance in individuals with diabetic neuropathy may have some limitations. These programs can sometimes be ineffective due to reduced sensory feedback, slow progress, and difficulty in fully restoring postural stability [20].

Whole-body vibration (WBV) therapy has been shown to enhance strength, balance, mobility, and circulation, particularly in older adults. It has also proven effective in rehabilitating conditions like musculoskeletal pain and managing diabetes [21]. Treadmill training has emerged as another effective rehabilitation method, significantly improving gait speed, cardiovascular parameters, and postural balance. Inclined treadmill training enhances hip, knee, and ankle angles while increasing amplitude and stance time in the lower limbs [22, 23]. However, studies on WBV training in stroke rehabilitation have produced mixed results. Some studies have shown improvements in balance and walking function, while others found no significant difference compared to routine rehabilitation [24].

Treadmills remain a widely used tool for enhancing dynamic balance and offer advantages over conventional rehabilitation. Inclined surfaces add complexity to locomotor control, particularly for individuals with neurological gait impairments. Adjustments in limb movement improve efficiency, increase mobility, and reduce balance-related risks [25]. Despite these promising interventions, most research on balance improvement in patients with diabetic neuropathy has focused on individual therapies. Few comparative studies have evaluated the relative effectiveness of WBV and treadmill training. There is limited evidence on their optimal use in correcting balance deficits. This research was conducted to assess and contrast the efficacy of WBV and inclined treadmill exercises in enhancing balance in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Since balance impairments are common in this group, the research aimed to identify which intervention provided more significant improvements.

Materials and Methods

Research design and sample

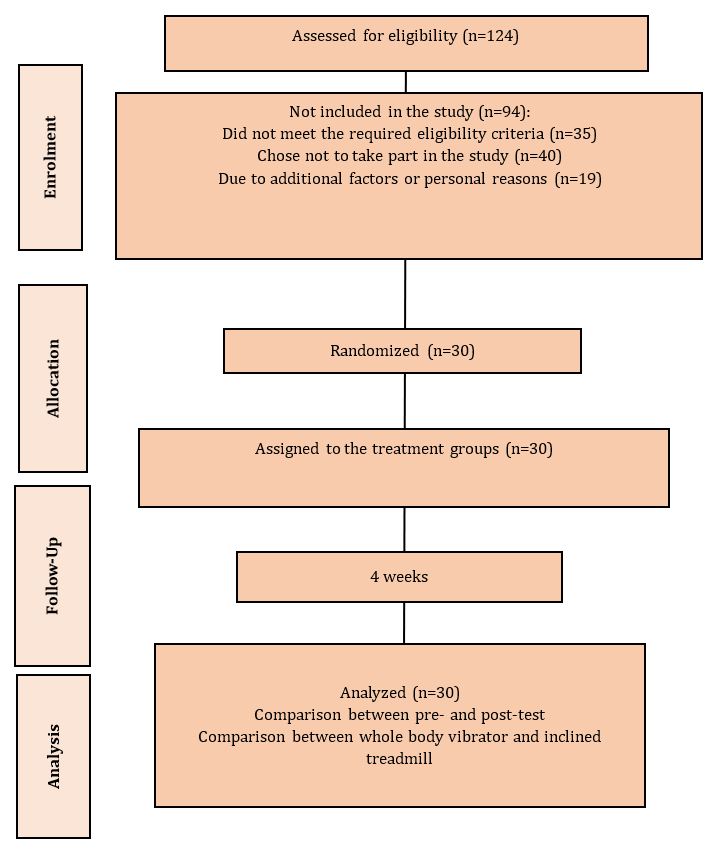

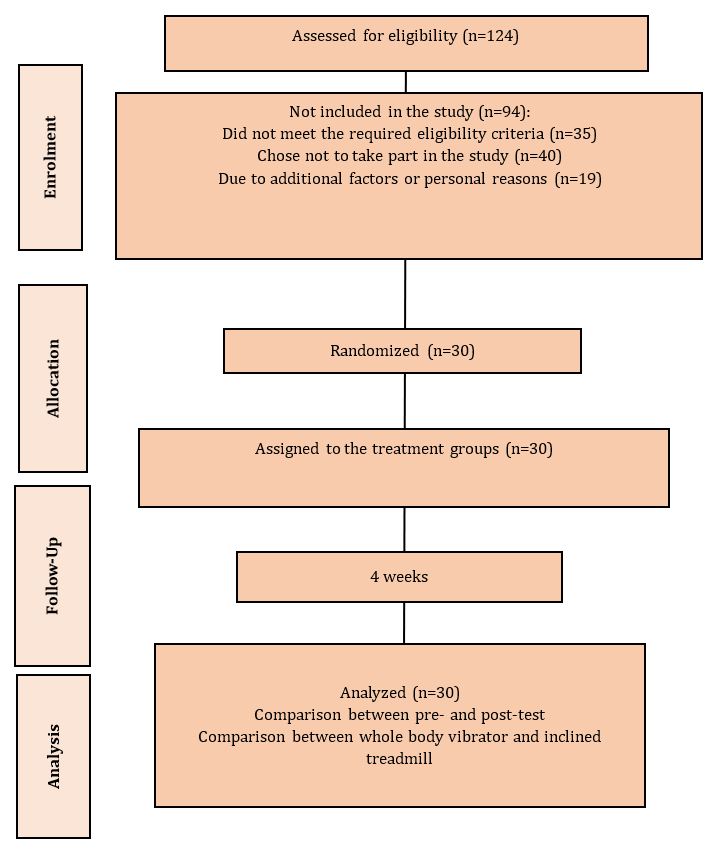

This comparative study was conducted involving individuals diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy at Saveetha Medical College and Hospital in Chennai, India, from July 2024 to December 2024. The sample size estimation was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4), considering the expected therapeutic impact on both absolute and relative power measures. The statistical parameters used for the calculation included a t-test with an alpha value of 0.05, a medium effect size (Cohen’s d=0.5), and a statistical power of 80%. This calculation indicated that a minimum of 30 participants would be sufficient to detect the expected therapeutic effect, even after accounting for a 10% dropout rate. A total of 124 individuals were screened for eligibility, of whom 94 were excluded for reasons, such as not meeting the inclusion criteria, declining participation, or incomplete baseline assessments. Finally, 30 participants were enrolled, matching the required sample size (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study enrolment flowchart

All 30 participants were given a clear explanation of the study; their informed consent was obtained, and baseline characteristics were recorded. They were randomly assigned to two groups using simple random sampling through the lottery method: Group A (15 participants) and Group B (15 participants). To minimize detection bias, the randomization process was conducted with assessor blinding. Therefore, the total estimated sample size was 30 patients.

Regarding gender, the male to female ratio in Group A was 8:7 and in Group B, it was 9:6. The mean age for Group A was 59.53±7.03 years, while for Group B, it was 61.53±7.44 years. The mean HbA1c levels in Group A were 8.80±1.19, compared to 8.74±0.98 in Group B. The mean BMI for Group A was 25.90±2.54kg/m², whereas for Group B, it was 27.50±2.67kg/m².

The individuals included in the study were aged between 50 and 80 years and were confirmed cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus persisting for over ten years, with poor glycemic control. All participants presented with diabetic polyneuropathy and had glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels ranging from 7% to 11%, alongside fasting plasma blood glucose concentrations ranging from 7.0 to 11.1mmol/L. Functional balance assessments indicated moderate impairment, with BBS scores falling between 21 and 40. Additionally, participants exhibited a TUG test time exceeding 10 seconds but not surpassing 30 seconds.

Participants were excluded if they had undergone recent surgical procedures or sustained injuries affecting lower limb function. Other exclusion criteria included malnutrition, characterized by a BMI of less than 21kg/m² or a significant, unintended reduction in body weight over the previous six months. Individuals with active foot ulcers, a history of major cardiovascular incidents, or severe musculoskeletal or neurological disorders impacting mobility were also not eligible for the study.

The interventions were provided by experienced physiotherapists familiar with the specific techniques used in the study. To maintain consistency and competence, all physiotherapists underwent a comprehensive training program on the intervention procedures. All missed appointments and any protocol deviations were documented and discussed to ensure standardization in the delivery of the interventions.

Tools

Berg balance scale (BBS)

The BBS is a tool designed to evaluate both static and dynamic balance, especially in older adults. It has a maximum score of 56 and comprises 14 tasks with scores ranging from 0 to 4. The test, which usually takes 15 to 20 minutes, assesses functional mobility and fall risk. Each task gradually increases in difficulty, and each component is assessed using a five-point scale ranging from 0 to 4. The highest attainable score is 56, where lower totals indicate greater impairment in balance. The BBS demonstrates excellent validity and shows strong consistency between different raters (inter-rater reliability of 0.97) and across repeated assessments by the same rater (intra-rater reliability of 0.98). Its overall reliability varies across the scale, with minimal detectable change and more homogeneity at the higher end of the scoring range [26].

Time up and go test (TUG)

The TUG test evaluates functional mobility and balance. After being seated, the participants were instructed to walk three meters, turn around, return to their chairs, and sit down. The timer started with the “ready, set, go” signal and stopped when the individual sat down. The average of the three test results was used to calculate the mean TUG score. The TUG test has proven to be both reliable and valid, with strong recognition as a functional mobility assessment tool. It has demonstrated excellent concurrent validity with physical movements and has a high level of consistency for both intra- and inter-rater reliability (ICC=0.99) [27].

Procedure

Group A received WBV for 25 minutes, four times weekly, while Group B received inclined treadmill training for the same duration. Each intervention was administered four times per week over a period of four weeks. To assess their effectiveness, post-treatment results were measured using the BBS and the TUG test.

WBV therapy

The session commenced with the patient standing barefoot on the vibration platform to facilitate equal weight distribution between the two feet. To acclimate the patient to the sensation of WBV, the initial exposure was provided at a lower frequency and amplitude before progressing to the prescribed parameters of 30Hz frequency and 2mm amplitude. The patient began in a position of knee flexion at approximately 30 degrees, performing five repetitions of 30 seconds of vibration, with a one-minute pause in between. Following knee flexion, the patient performed a series of functional movements on the platform, which were designed to provoke maximum muscle activation and enhance balance.

The exercises employed in the study included squats, performed in three sets of one minute with 30 seconds of rest in between; tandem stance, performed in two sets of one minute with 30 seconds of rest in between; and alternating lunges, performed in three sets of one minute with 30 seconds of rest in between. The overall program was planned to take approximately 25 minutes, thereby progressively challenging postural control and dynamic stability [28].

Inclined treadmill training

During the therapy session, patients walked on a treadmill at speeds between 1.2 and 1.6m/sec. As they improved, the speed was gradually increased to the highest level they felt comfortable with, while maintaining an upright posture. If they felt unsteady or uncomfortable, they were encouraged to hold onto the rails for support, and assistance was provided when needed. The session included walking at a 10% incline for 10 minutes, followed by a 5-minute rest, and then another 10 minutes at a 20% incline [29].

Data analysis

SPSS 29 was used to perform both descriptive and inferential analyses. All statistical tests were conducted at a 95% confidence interval. Paired t-tests were used to evaluate changes within each group over the course of the study, while independent t-tests were applied to compare the outcomes between the two groups following the intervention.

Findings

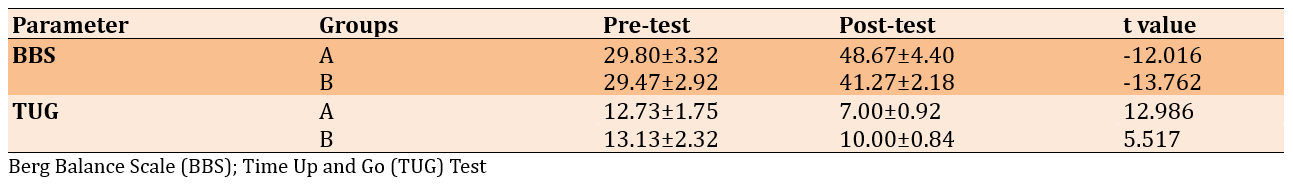

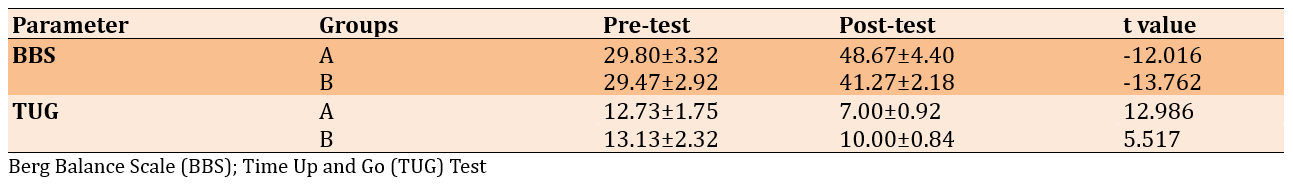

Patients with DPN who received WBV therapy (Group A) and inclined treadmill training (Group B) showed significant improvements, with small differences between the groups (p-value<0.001). Among them, those who received WBV therapy demonstrated better improvement. Members of Group A had larger gains in their BBS scores compared to those in Group B, with Group A showing a mean score of 48.67±4.40 and Group B averaging 41.27±2.18. Additionally, Group A also exhibited improvement in the TUG test, achieving a mean of 7.00±0.92, while Group B had a mean of 10.00±0.84 (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of mean within-group BBS and TUG scores

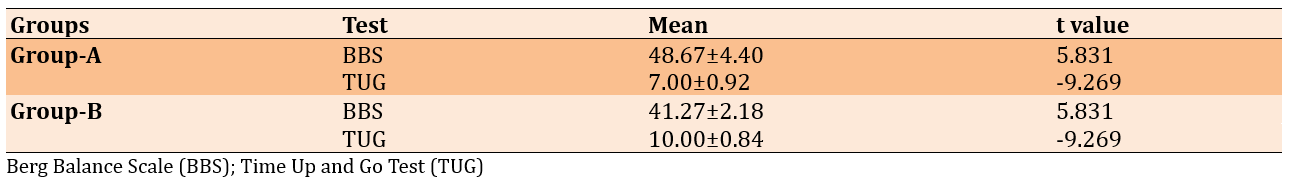

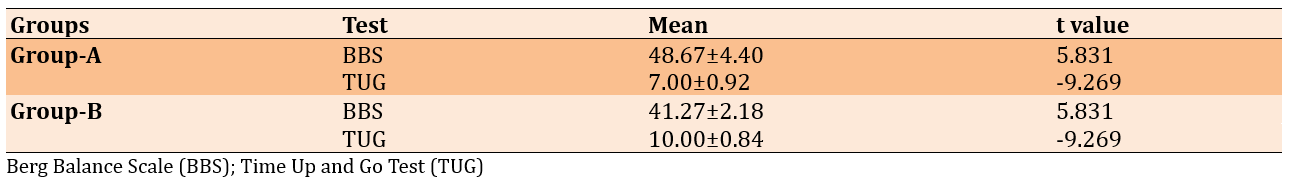

The findings were further supported by effect size analysis, which indicated substantial impacts. In Group A, the estimated Cohen’s d values were 6.081 for BBS and 1.710 for TUG, reflecting strong effects. Similarly, Group B also demonstrated remarkable effect sizes, with Cohen’s d calculated at 3.321 for BBS and 2.200 for TUG. Although each intervention resulted in meaningful statistical improvements (p<0.001), the greater mean differences and effect sizes suggest that WBV therapy was a more effective method for enhancing balance and mobility in patients with diabetic neuropathy (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of between-group post-test BBS and TUG scores

Discussion

We compared the effectiveness of two rehabilitation modalities, namely WBV therapy (Group A) and inclined treadmill training (Group B). Both groups showed significant improvements in functional outcomes. Remarkably, WBV therapy was particularly effective in enhancing balance and neuromuscular control.

There was a significant improvement in the BBS scores of patients who received WBV therapy. This result is consistent with earlier research findings that have shown significant improvements in balance outcomes following WBV interventions. Subjects who receive balance training in addition to WBV had larger gains in BBS scores and postural control compared to subjects who received only balance training [30]. These findings align with those of previous studies reporting remarkable improvements in clinical measures of balance following a WBV exercise program. Although such encouraging results have been documented, potential limitations should be considered [31].

Heterogeneity in WBV protocols, including variations in frequency, amplitude, and duration of sessions, could influence both the efficacy of the intervention and the comparability of studies among them [32]. Additionally, the long-term gains in balance retained following WBV treatment remain uncertain, particularly for patients with conditions such as diabetic neuropathy. To address the inconsistency in WBV, our study implemented a standardized protocol.

Aside from enhancing mobility and balance, WBV therapy has also been shown to improve confidence in movement and the ability to perform activities of daily living. However, some studies have raised concerns about its potential side effects. The researchers hypothesized that WBV temporarily disrupts the somatosensory system, leading to balance disturbances and an increased risk of falls [33].

Moreover, the use of WBV activates the tonic vibration reflex, triggering involuntary muscle contractions that enhance postural support and balance. It also stimulates both agonist and antagonist muscles, promoting muscular balance and reducing the risk of injury, ultimately resulting in greater overall stability and strength [34]. On the other hand, WBV therapy provides a safe and gentle approach to improving balance and stability, making it a valuable tool in rehabilitation programs [35].

While inclined treadmills have demonstrated strong effects compared to other types of treadmill training, previous research has also supported their specific benefits. For instance, it was found that 10 weeks of inclined treadmill training not only significantly improves walking ability and balance but also has no adverse effects on muscle function in patients [36]. Similarly, using a tilted treadmill for walking can enhance postural balance and gait by promoting increased dorsiflexion of the ankle, leading to a more vertical pelvis and trunk alignment. These beneficial effects indicate that walking on an inclined treadmill is an effective method for stabilizing the lower limbs.

In general, research shows that WBV is effective in enhancing balance, gait function, and functional mobility in individuals with diabetic neuropathy. It provides a sense of confidence and can be integrated into individual or group rehabilitation programs.

This study has several limitations, including the absence of double blinding, the lack of a control group, a relatively short intervention duration, and inconsistent patient adherence. Future investigations should consider incorporating emerging technologies such as mixed reality, wearable devices, and individualized training programs to enhance treatment outcomes. Moreover, examining the combined effects of WBV therapy with pharmacological or nutritional support may provide valuable insights for improving balance-related results. Expanding research to include more diverse populations and longer intervention periods will be critical for establishing more robust and generalizable treatment approaches. Addressing these aspects is essential for advancing effective and reliable therapeutic strategies.

Both WBV therapy and inclined treadmill training led to comparable improvements in participants, with a statistically significant distinction observed between the two groups. Nevertheless, WBV therapy demonstrated promising results in enhancing balance and postural control. As a non-surgical intervention, WBV appears to be an effective option for addressing balance issues in individuals with diabetic neuropathy.

Conclusion

WBV and inclined treadmill training significantly improve balance, but whole-body vibration is more effective in enhancing stability and reducing fall risk.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge the University for providing technical guidance. We also extend our sincere thanks to all study participants for their valuable contributions.

Ethical Permissions: The study adhered to the ethical guidelines established by the Institutional Scientific Research Board on Human Experimentation (377/07/2024/ISRB/UGSR/SCPT).

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interests exist.

Authors' Contribution: Dhanusia S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (25%); Bai P (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (20%); Sahal M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%); Suganthirababu P (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Jayaraj V (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (10%); Kumar P (Sixth Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (10%); Srinivasan V (Seventh Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (5%)

Funding/Support: This study was self-funded with no external funding or financial support involved.

Diabetes is a disease that involves the dysfunctional release of insulin, which causes blood sugar levels to rise and poses risks for heart attacks, high blood pressure, kidney failure, and death. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the number of diagnosed individuals with diabetes will increase from 138 million to 202 million by 2035 [1, 2]. Diabetic neuropathy is a nervous system manifestation of diabetes mellitus. It occurs because high blood sugar levels damage small blood vessels over time; this complication can harm the peripheral nerve fibers and impair the function of the peripheral nervous system [3, 4]. Diabetic neuropathies encompass a broad range of disorders characterized by various neurological impairments. They are among the most frequent and serious long-term complications of diabetes, significantly contributing to illness and mortality. This condition can develop in individuals with any form of diabetes, including both insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent types [5]. Neuropathic manifestations are generally classified as either somatic or autonomic. Among the earliest and most common symptoms of diabetic neuropathy are paraesthesia, tingling, or prickling sensations in the legs and feet. As the condition advances, these symptoms often progress to numbness caused by sensory nerve damage, eventually resulting in a reduced or complete loss of touch, pain, temperature, vibration, and proprioception [6-9].

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) can influence balance as it affects the body’s capacity to detect and react to shifts in position. Consequently, individuals have difficulty maintaining a stable center of gravity, especially when standing or walking. This results in reduced feedback and an impaired motor response, making it more challenging to make postural adjustments, which can lead to an increased risk of falls and instability [10]. The prevalence of balance impairment increases with the duration of diabetes and poorer glycemic control. Research suggests that about 16% of those with diabetes experience balance problems, rising to between 30% and 50% as the condition worsens [11, 12]. In addition, damage to sensory nerves caused by diabetic neuropathy can reduce proprioceptive awareness, affecting joint position and limb movement. This may lead to impaired balance and coordination, especially during weight shifts and precise actions [13]. Balance issues in DPN arise from sensory loss, motor dysfunction, proprioceptive impairments, muscle weakness, and alterations in gait [14, 15].

A range of medications is available to manage diabetes, with treatment plans typically tailored to individual needs [16, 17]. Metformin is commonly the first drug of choice; it lowers the production of glucose in the liver and enhances the body’s sensitivity to insulin. Sulfonylureas, such as glipizide, work by stimulating the pancreas to produce increased amounts of insulin. Meanwhile, SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin help control blood sugar levels by promoting the excretion of glucose through urine [18]. Although there are many pharmacological treatment options for diabetes, the literature shows that they are not adequately effective, as diabetes is a multifactorial disorder. For example, sulfonylureas carry a higher risk of heart failure with high-dose monotherapy [19]. Traditional rehabilitation methods for balance in individuals with diabetic neuropathy may have some limitations. These programs can sometimes be ineffective due to reduced sensory feedback, slow progress, and difficulty in fully restoring postural stability [20].

Whole-body vibration (WBV) therapy has been shown to enhance strength, balance, mobility, and circulation, particularly in older adults. It has also proven effective in rehabilitating conditions like musculoskeletal pain and managing diabetes [21]. Treadmill training has emerged as another effective rehabilitation method, significantly improving gait speed, cardiovascular parameters, and postural balance. Inclined treadmill training enhances hip, knee, and ankle angles while increasing amplitude and stance time in the lower limbs [22, 23]. However, studies on WBV training in stroke rehabilitation have produced mixed results. Some studies have shown improvements in balance and walking function, while others found no significant difference compared to routine rehabilitation [24].

Treadmills remain a widely used tool for enhancing dynamic balance and offer advantages over conventional rehabilitation. Inclined surfaces add complexity to locomotor control, particularly for individuals with neurological gait impairments. Adjustments in limb movement improve efficiency, increase mobility, and reduce balance-related risks [25]. Despite these promising interventions, most research on balance improvement in patients with diabetic neuropathy has focused on individual therapies. Few comparative studies have evaluated the relative effectiveness of WBV and treadmill training. There is limited evidence on their optimal use in correcting balance deficits. This research was conducted to assess and contrast the efficacy of WBV and inclined treadmill exercises in enhancing balance in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Since balance impairments are common in this group, the research aimed to identify which intervention provided more significant improvements.

Materials and Methods

Research design and sample

This comparative study was conducted involving individuals diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy at Saveetha Medical College and Hospital in Chennai, India, from July 2024 to December 2024. The sample size estimation was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4), considering the expected therapeutic impact on both absolute and relative power measures. The statistical parameters used for the calculation included a t-test with an alpha value of 0.05, a medium effect size (Cohen’s d=0.5), and a statistical power of 80%. This calculation indicated that a minimum of 30 participants would be sufficient to detect the expected therapeutic effect, even after accounting for a 10% dropout rate. A total of 124 individuals were screened for eligibility, of whom 94 were excluded for reasons, such as not meeting the inclusion criteria, declining participation, or incomplete baseline assessments. Finally, 30 participants were enrolled, matching the required sample size (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study enrolment flowchart

All 30 participants were given a clear explanation of the study; their informed consent was obtained, and baseline characteristics were recorded. They were randomly assigned to two groups using simple random sampling through the lottery method: Group A (15 participants) and Group B (15 participants). To minimize detection bias, the randomization process was conducted with assessor blinding. Therefore, the total estimated sample size was 30 patients.

Regarding gender, the male to female ratio in Group A was 8:7 and in Group B, it was 9:6. The mean age for Group A was 59.53±7.03 years, while for Group B, it was 61.53±7.44 years. The mean HbA1c levels in Group A were 8.80±1.19, compared to 8.74±0.98 in Group B. The mean BMI for Group A was 25.90±2.54kg/m², whereas for Group B, it was 27.50±2.67kg/m².

The individuals included in the study were aged between 50 and 80 years and were confirmed cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus persisting for over ten years, with poor glycemic control. All participants presented with diabetic polyneuropathy and had glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels ranging from 7% to 11%, alongside fasting plasma blood glucose concentrations ranging from 7.0 to 11.1mmol/L. Functional balance assessments indicated moderate impairment, with BBS scores falling between 21 and 40. Additionally, participants exhibited a TUG test time exceeding 10 seconds but not surpassing 30 seconds.

Participants were excluded if they had undergone recent surgical procedures or sustained injuries affecting lower limb function. Other exclusion criteria included malnutrition, characterized by a BMI of less than 21kg/m² or a significant, unintended reduction in body weight over the previous six months. Individuals with active foot ulcers, a history of major cardiovascular incidents, or severe musculoskeletal or neurological disorders impacting mobility were also not eligible for the study.

The interventions were provided by experienced physiotherapists familiar with the specific techniques used in the study. To maintain consistency and competence, all physiotherapists underwent a comprehensive training program on the intervention procedures. All missed appointments and any protocol deviations were documented and discussed to ensure standardization in the delivery of the interventions.

Tools

Berg balance scale (BBS)

The BBS is a tool designed to evaluate both static and dynamic balance, especially in older adults. It has a maximum score of 56 and comprises 14 tasks with scores ranging from 0 to 4. The test, which usually takes 15 to 20 minutes, assesses functional mobility and fall risk. Each task gradually increases in difficulty, and each component is assessed using a five-point scale ranging from 0 to 4. The highest attainable score is 56, where lower totals indicate greater impairment in balance. The BBS demonstrates excellent validity and shows strong consistency between different raters (inter-rater reliability of 0.97) and across repeated assessments by the same rater (intra-rater reliability of 0.98). Its overall reliability varies across the scale, with minimal detectable change and more homogeneity at the higher end of the scoring range [26].

Time up and go test (TUG)

The TUG test evaluates functional mobility and balance. After being seated, the participants were instructed to walk three meters, turn around, return to their chairs, and sit down. The timer started with the “ready, set, go” signal and stopped when the individual sat down. The average of the three test results was used to calculate the mean TUG score. The TUG test has proven to be both reliable and valid, with strong recognition as a functional mobility assessment tool. It has demonstrated excellent concurrent validity with physical movements and has a high level of consistency for both intra- and inter-rater reliability (ICC=0.99) [27].

Procedure

Group A received WBV for 25 minutes, four times weekly, while Group B received inclined treadmill training for the same duration. Each intervention was administered four times per week over a period of four weeks. To assess their effectiveness, post-treatment results were measured using the BBS and the TUG test.

WBV therapy

The session commenced with the patient standing barefoot on the vibration platform to facilitate equal weight distribution between the two feet. To acclimate the patient to the sensation of WBV, the initial exposure was provided at a lower frequency and amplitude before progressing to the prescribed parameters of 30Hz frequency and 2mm amplitude. The patient began in a position of knee flexion at approximately 30 degrees, performing five repetitions of 30 seconds of vibration, with a one-minute pause in between. Following knee flexion, the patient performed a series of functional movements on the platform, which were designed to provoke maximum muscle activation and enhance balance.

The exercises employed in the study included squats, performed in three sets of one minute with 30 seconds of rest in between; tandem stance, performed in two sets of one minute with 30 seconds of rest in between; and alternating lunges, performed in three sets of one minute with 30 seconds of rest in between. The overall program was planned to take approximately 25 minutes, thereby progressively challenging postural control and dynamic stability [28].

Inclined treadmill training

During the therapy session, patients walked on a treadmill at speeds between 1.2 and 1.6m/sec. As they improved, the speed was gradually increased to the highest level they felt comfortable with, while maintaining an upright posture. If they felt unsteady or uncomfortable, they were encouraged to hold onto the rails for support, and assistance was provided when needed. The session included walking at a 10% incline for 10 minutes, followed by a 5-minute rest, and then another 10 minutes at a 20% incline [29].

Data analysis

SPSS 29 was used to perform both descriptive and inferential analyses. All statistical tests were conducted at a 95% confidence interval. Paired t-tests were used to evaluate changes within each group over the course of the study, while independent t-tests were applied to compare the outcomes between the two groups following the intervention.

Findings

Patients with DPN who received WBV therapy (Group A) and inclined treadmill training (Group B) showed significant improvements, with small differences between the groups (p-value<0.001). Among them, those who received WBV therapy demonstrated better improvement. Members of Group A had larger gains in their BBS scores compared to those in Group B, with Group A showing a mean score of 48.67±4.40 and Group B averaging 41.27±2.18. Additionally, Group A also exhibited improvement in the TUG test, achieving a mean of 7.00±0.92, while Group B had a mean of 10.00±0.84 (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of mean within-group BBS and TUG scores

The findings were further supported by effect size analysis, which indicated substantial impacts. In Group A, the estimated Cohen’s d values were 6.081 for BBS and 1.710 for TUG, reflecting strong effects. Similarly, Group B also demonstrated remarkable effect sizes, with Cohen’s d calculated at 3.321 for BBS and 2.200 for TUG. Although each intervention resulted in meaningful statistical improvements (p<0.001), the greater mean differences and effect sizes suggest that WBV therapy was a more effective method for enhancing balance and mobility in patients with diabetic neuropathy (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of between-group post-test BBS and TUG scores

Discussion

We compared the effectiveness of two rehabilitation modalities, namely WBV therapy (Group A) and inclined treadmill training (Group B). Both groups showed significant improvements in functional outcomes. Remarkably, WBV therapy was particularly effective in enhancing balance and neuromuscular control.

There was a significant improvement in the BBS scores of patients who received WBV therapy. This result is consistent with earlier research findings that have shown significant improvements in balance outcomes following WBV interventions. Subjects who receive balance training in addition to WBV had larger gains in BBS scores and postural control compared to subjects who received only balance training [30]. These findings align with those of previous studies reporting remarkable improvements in clinical measures of balance following a WBV exercise program. Although such encouraging results have been documented, potential limitations should be considered [31].

Heterogeneity in WBV protocols, including variations in frequency, amplitude, and duration of sessions, could influence both the efficacy of the intervention and the comparability of studies among them [32]. Additionally, the long-term gains in balance retained following WBV treatment remain uncertain, particularly for patients with conditions such as diabetic neuropathy. To address the inconsistency in WBV, our study implemented a standardized protocol.

Aside from enhancing mobility and balance, WBV therapy has also been shown to improve confidence in movement and the ability to perform activities of daily living. However, some studies have raised concerns about its potential side effects. The researchers hypothesized that WBV temporarily disrupts the somatosensory system, leading to balance disturbances and an increased risk of falls [33].

Moreover, the use of WBV activates the tonic vibration reflex, triggering involuntary muscle contractions that enhance postural support and balance. It also stimulates both agonist and antagonist muscles, promoting muscular balance and reducing the risk of injury, ultimately resulting in greater overall stability and strength [34]. On the other hand, WBV therapy provides a safe and gentle approach to improving balance and stability, making it a valuable tool in rehabilitation programs [35].

While inclined treadmills have demonstrated strong effects compared to other types of treadmill training, previous research has also supported their specific benefits. For instance, it was found that 10 weeks of inclined treadmill training not only significantly improves walking ability and balance but also has no adverse effects on muscle function in patients [36]. Similarly, using a tilted treadmill for walking can enhance postural balance and gait by promoting increased dorsiflexion of the ankle, leading to a more vertical pelvis and trunk alignment. These beneficial effects indicate that walking on an inclined treadmill is an effective method for stabilizing the lower limbs.

In general, research shows that WBV is effective in enhancing balance, gait function, and functional mobility in individuals with diabetic neuropathy. It provides a sense of confidence and can be integrated into individual or group rehabilitation programs.

This study has several limitations, including the absence of double blinding, the lack of a control group, a relatively short intervention duration, and inconsistent patient adherence. Future investigations should consider incorporating emerging technologies such as mixed reality, wearable devices, and individualized training programs to enhance treatment outcomes. Moreover, examining the combined effects of WBV therapy with pharmacological or nutritional support may provide valuable insights for improving balance-related results. Expanding research to include more diverse populations and longer intervention periods will be critical for establishing more robust and generalizable treatment approaches. Addressing these aspects is essential for advancing effective and reliable therapeutic strategies.

Both WBV therapy and inclined treadmill training led to comparable improvements in participants, with a statistically significant distinction observed between the two groups. Nevertheless, WBV therapy demonstrated promising results in enhancing balance and postural control. As a non-surgical intervention, WBV appears to be an effective option for addressing balance issues in individuals with diabetic neuropathy.

Conclusion

WBV and inclined treadmill training significantly improve balance, but whole-body vibration is more effective in enhancing stability and reducing fall risk.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge the University for providing technical guidance. We also extend our sincere thanks to all study participants for their valuable contributions.

Ethical Permissions: The study adhered to the ethical guidelines established by the Institutional Scientific Research Board on Human Experimentation (377/07/2024/ISRB/UGSR/SCPT).

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interests exist.

Authors' Contribution: Dhanusia S (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (25%); Bai P (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (20%); Sahal M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (15%); Suganthirababu P (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (15%); Jayaraj V (Fifth Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (10%); Kumar P (Sixth Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (10%); Srinivasan V (Seventh Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (5%)

Funding/Support: This study was self-funded with no external funding or financial support involved.

Keywords:

References

1. Abraham MM, Tyng TS, Rekha K, Shanmugananth E, Kiruthika S. Comparison of four screening methods for diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A cross sectional study. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2018;11(12):5551-8. [Link] [DOI:10.5958/0974-360X.2018.01010.7]

2. Yıldırım T, Önalan R. What is the role of oxidative stress in the development of diabetic peripheral neuropathy?. Journal of Surgery and Medicine. 2021;5(5):408-11. [Link] [DOI:10.28982/josam.889008]

3. Kalpana R, Kothandaraman K, Anuradha P. Association of peripheral neuropathy with retinopathy in diabetic patients. Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2018;4(1):115-9. [Link] [DOI:10.18231/2395-1451.2018.0026]

4. Reyhanoğlu DA, Kara B, Şengün İŞ, Yıldırım G. Biomechanical changes observed in diabetic neuropathy. DOKUZ EYLÜL ÜNIVERSITESI TIP FAKÜLTESI DERGISI. 2018;32(2):167-72. [Turkish] [Link] [DOI:10.5505/deutfd.2018.36449]

5. Manorma MR, RANI A, BUDHORI R, KAUSHIK A. Current measures against ophthalmic complications of diabetes mellitus-A short review. Int J Appl Pharm. 2021;13(6):54-65. [Link] [DOI:10.22159/ijap.2021v13i6.42876]

6. Bansal V, Kalita J, Misra UK. Diabetic neuropathy. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(964):95-100. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/pgmj.2005.036137]

7. Jannu C, Babu PS, Puchchakayala G, Chandupatla VD. Efficacy of interferential therapy versus transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation to reduce pain in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9(10):121-4. [Link] [DOI:10.5958/0976-5506.2018.01325.6]

8. Mohi WZ, Shemran KA, Alsaffar Y. Comparison of visfatin and leptin levels in type 2 diabetic patients with and without atherosclerosis. Iran J War Public Health. 2023;15(1):11-5. [Link]

9. Yousif AMA, Sokrab TEO, Tawfik H, Abdelbagi I, Mazin SA, Sharaf R, et al. Patients' perception on benefits of medications for treating diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Texila Int J Clin Res. 2017;4(2). [Link] [DOI:10.21522/TIJCR.2014.04.02.Art002]

10. Yagihashi S, Mizukami H, Sugimoto K. Mechanism of diabetic neuropathy: Where are we now and where to go?. J Diabetes Investig. 2011;2(1):18-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00070.x]

11. Kumar A, Dharshini D. Effect of vestibular based balance training among diabetic neuropathy patient. CUESTIONES DE FISIOTERAPIA. 2025;54(4):5748-54. [Link] [DOI:10.48047/w0038079]

12. Demirağ H, Hintistan S, Tuncay B, Cin A. Health services determination of diabetes risks of vocational high school students. İNÖNÜ ÜNIVERSITESI SAĞLIK HIZMETLERI MESLEK YÜKSEK OKULU DERGISI. 2018;6(2):25-35. [Turkish] [Link]

13. Jamal A, Ahmad I, Ahamed N, Azharuddin M, Alam F, Hussain ME. Whole body vibration showed beneficial effect on pain, balance measures and quality of life in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019;19(1):61-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40200-019-00476-1]

14. Ites KI, Anderson EJ, Cahill ML, Kearney JA, Post EC, Gilchrist LS. Balance interventions for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2011;34(3):109-16. [Link] [DOI:10.1519/JPT.0b013e318212659a]

15. Vasudhevan AS, Sumathi DM, Selvakumar AK, Rajabalaji R. A comparative study of mean platelet volume in diabetic population with and without vascular complication. Indones J Med Lab Sci Technol. 2023;5(1):42-52. [Link] [DOI:10.33086/ijmlst.v5i1.3465]

16. Alwatify SS, Radhi MM. Diabetes self-management and its association with medication adherence in diabetic patients. Iran J War Public Health. 2025;17(1):17-22. [Link] [DOI:10.58209/ijwph.17.1.17]

17. Hadi HS, Enayah SH. RETN gene polymorphisms as a risk factor in diabetic patients with Covid-19 infection. Iran J War Public Health. 2023;15(1):1-9. [Link] [DOI:10.32792/utq/utjsci/v9i2.906]

18. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S11-61. [Link] [DOI:10.2337/dc11-S011]

19. Pasupulati H, Swathi B, Tahseen S, Anwer MS, Sandhya R, Fathima S, et al. An observational study of peripheral neuropathy in diabetes patients on metformin therapy and the role of vitamin b-12 supplementation. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024;16(12):21-5. [Link] [DOI:10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i12.52405]

20. Jo NG, Kang SR, Ko MH, Yoon JY, Kim HS, Han KS, et al. Effectiveness of whole-body vibration training to improve muscle strength and physical performance in older adults: Prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Healthcare. 2021;9(6):652. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare9060652]

21. Ribeiro TS, Silva EM, Silva IA, Costa MF, Cavalcanti FA, Lindquist AR. Effects of treadmill training with load addition on non-paretic lower limb on gait parameters after stroke: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Gait Posture. 2017;54:229-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.03.008]

22. Hamed MM, Sayed AA, Naseif NL, Fouad SA. Effect of different treadmill inclination training on postural balance in elderly. Med J Cairo Univ. 2022;90(9):1515-21. [Link] [DOI:10.21608/mjcu.2022.264608]

23. Patel B, Shah C, Shah S. Test-retest reliability of berg balance scale in subjects with diabetic neuropathy: A pilot study. JETIR. 2019;6(6):272-5. [Link]

24. Ahmed GM, Fahmy EM, Elwishy AA, Mounir KM, Zidan FS. Effects of inclined treadmill training on gait and balance in stroke patients. NY Sci J. 2018;11(4):52-6. [Link]

25. Rittweger J. Vibration as an exercise modality: How it may work, and what its potential might be. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):877-904. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00421-009-1303-3]

26. Avers D. Functional performance measures and assessment for older adults. In: Guccione's geriatric physical therapy. New York: Elsevier; 2020. p. 137-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-323-60912-8.00007-5]

27. Waheed A, Azharuddin M, Ahmad I, Noohu MM. Whole-body vibration, in addition to balance exercise, shows positive effects for strength and functional ability in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Diabetol. 2021;12(4):456-63. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jod.jod_47_21]

28. Geroin C, Mazzoleni S, Smania N, Gandolfi M, Bonaiuti D, Gasperini G, et al. Systematic review of outcome measures of walking training using electromechanical and robotic devices in patients with stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(10):987-96. [Link] [DOI:10.2340/16501977-1234]

29. Downs S, Marquez J, Chiarelli P. The berg balance scale has high intra-and inter-rater reliability but absolute reliability varies across the scale: A systematic review. J Physiother. 2013;59(2):93-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70161-9]

30. Stambolieva K, Petrova D, Irikeva M. Positive effects of plantar vibration training for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A pilot study. Somatosens Mot Res. 2017;34(2):129-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08990220.2017.1332585]

31. Kordi Yoosefinejad A, Shadmehr A, Olyaei G, Talebian S, Bagheri H, Mohajeri-Tehrani MR. Short-term effects of the whole-body vibration on the balance and muscle strength of type 2 diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy: A quasi-randomized-controlled trial study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14(1):45. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40200-015-0173-y]

32. Paz GA, Almeida L, Ruiz L, Casseres S, Xavier G, Lucas J, et al. Myoelectric responses of lower-body muscles performing squat and lunge exercise variations adopting visual feedback with a laser sensor. J Sport Rehabil. 2020;29(8):1159-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1123/jsr.2019-0194]

33. Torvinen S, Kannus P, Sievänen H, Järvinen TA, Pasanen M, Kontulainen S, et al. Effect of four-month vertical whole body vibration on performance and balance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(9):1523-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00005768-200209000-00020]

34. Zafar T, Zaki S, Alam MF, Sharma S, Babkair RA, Nuhmani S, et al. Effect of whole-body vibration exercise on pain, disability, balance, proprioception, functional performance and quality of life in people with non-specific chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2024;13(6):1639. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/jcm13061639]

35. Ferraro RA, Pinto-Zipp G, Simpkins S, Clark M. Effects of an inclined walking surface and balance abilities on spatiotemporal gait parameters of older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2013;36(1):31-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182510339]

36. Abdelaal A, El-Shamy S. Effect of antigravity treadmill training on gait and balance in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy: A randomized controlled trial. F1000Res. 2022;11:52. [Link] [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.75806.3]