Volume 16, Issue 3 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(3): 301-308 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/10/29 | Accepted: 2024/11/28 | Published: 2024/12/18

Received: 2024/10/29 | Accepted: 2024/11/28 | Published: 2024/12/18

How to cite this article

Elahian M, Rezakhani S, Dokanehifard F. Relationship between Religious Attitude and Spiritual Intelligence with Psychological Capital in Veterans' Children, Mediating Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (3) :301-308

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1518-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1518-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Counseling, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (479 Views)

Introduction

War-related trauma not only creates challenges for veterans, but it also indirectly affects their families and children, who experience psychological stress and may exhibit symptoms similar to those of their fathers [1, 2]. Secondary traumatic stress refers to the transmission of symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder from an individual who has been directly exposed to a traumatic event to another individual with whom they have close and ongoing contact [3]. In this context, the systematic secondary trauma model theory suggests that when a survivor of primary trauma (the veteran) exhibits trauma symptoms or low levels of functioning within the family system, a systematic response occurs. This response increases the likelihood of developing secondary traumatic stress symptoms in the spouse and family and refers to changes in the survivor’s beliefs about themselves, others, and the external world [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to address the various emotional and psychological issues faced by these individuals [5].

One of the most fundamental structures for the life and adaptation of veterans in response to adverse conditions is the application of a positive psychology approach. A key component of positive psychology is psychological capital, which is regarded as one of the most important characteristics for individuals’ adaptation to challenging circumstances and for improving their quality of life [6]. According to Luthans and Youssef, psychological capital comprises four constructs: hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Each of these can be viewed as a positive psychological capacity with the potential for growth and a significant relationship to performance outcomes [7]. Possessing psychological capital enables individuals to cope more effectively with stressful situations, experience less tension, demonstrate greater resilience in the face of challenges, maintain a clear self-perception, and be less affected by daily events [8].

Psychological capital predicts life satisfaction and flourishing [9], as well as health-promoting behaviors [10]. Additionally, the components of psychological capital have a significant relationship with post-traumatic growth [11, 12]. Cognitive reappraisal and positive psychological capital moderate the relationship between perceived stress and depression, significantly inhibiting depression in individuals with both high and low stress levels [13].

Spiritual intelligence is regarded as one of the effective variables for addressing the problems and tensions faced by the children of veterans. The effects of spiritual intelligence are extensive and encompass a wide range of human behavior. According to King, spiritual intelligence comprises a set of mental adaptive capacities that contribute to consciousness and, by integrating and adapting mental functions and higher aspects of existence, leads individuals to profound existential outcomes, enhancing meaning, recognizing a higher self, and mastering spiritual states [14]. Spiritual intelligence regulates the emotional domain [15], improves mental health [16], alleviates alexithymia, and promotes integrated self-awareness [17].

On the other hand, another issue concerning veterans and their families is their religious attitude. It appears that individuals who participated in the war have a high level of religious attitude. In the study by Kanani et al., it was demonstrated that religiosity and adherence to religious principles can positively influence various aspects of the quality of life of veterans [18]. Additionally, the results of another study indicated that the father-child relationship and the religious attitudes of students play an important and fundamental role in their social adaptation [19]. Based on these findings, religion plays a significant role in preventing the occurrence of diseases [20], promoting the psychological well-being of veterans’ spouses [21], and also impacting subjective well-being [22].

Another crucial and sensitive intrapersonal factor affecting interpersonal relationships in the children of veterans is cognitive emotion regulation. Javadpour et al. consider cognitive emotion regulation a type of social intelligence and have summarized it into five domains: Self-awareness, self-control, self-motivation, social awareness, and relationship regulation [23]. Cognitive emotion regulation is a means of understanding how an individual can organize their attention and take strategic and assertive actions to solve problems [24]. In other words, emotion regulation encompasses conscious or unconscious cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies used to maintain, increase, or decrease an emotion [25]. In this context, research findings indicate that effective emotion regulation can enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, enables individuals to respond adaptively to stress [26]. Additionally, people with higher emotion regulation have a greater ability to tolerate distress and are less impulsive [27]. Guo highlighted the special role of the dimensions of emotion regulation in relation to psychological capital and cognitive resilience [28].

Our country, a victim of war, has been extensively researched over the past half-century regarding the direct psychological impact of experiencing trauma. However, much less research has focused on the secondary effects of living with someone who has suffered from war trauma, as their children and families are indirectly affected by this trauma. Children of veterans were raised by fathers who experienced injuries and traumas from the war, and, conversely, the veterans’ attitudes toward life influence their communication patterns with their children. Accordingly, the present study aimed to investigate the causal relationships between religious attitude and spiritual intelligence, with psychological capital in children of veterans, while considering the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation.

Instrument and Methods

This research was fundamental in terms of its purpose and descriptive (correlational) in terms of the data collection method, utilizing structural equation model analysis. The research population consisted of all children of veterans living in Tehran, aged between 18 and 40. Their fathers were members of the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs in Tehran between April 2022 and September 2022. According to statistical information from the Foundation, the number of individuals was reported as 86,642. The sample size, based on Michel (1993, cited in Meyer et al., 2006), was estimated at 247 people and was increased to 260 to account for potential attrition. Consequently, 260 children of Iranian and Iraqi veterans completed the questionnaires online. It is worth noting that after eliminating seven incomplete questionnaires, 253 questionnaires were analyzed. Since the complete list of individuals in the research population was not available to the researcher, a convenience sampling method was employed. Four questionnaires were used in this study.

Religious Attitude Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by Khodayari Fard et al. in 2013 to measure religious attitudes and consists of 40 questions. It assesses four subscales: Religious belief, religious emotions, religious behavior, and social pretense. The subjects’ scores in response to each question are determined on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from always (5) to never (0). The total score for this questionnaire ranges from 40 to 200. A high score on each of the subscales indicates a person’s elevated level of attitude and beliefs regarding religious matters. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire have been reported as 0.96 and 0.94 in two studies [29]. The reliability coefficient obtained through the test-retest method was 0.91, while the split-half reliability, using the Spearman-Brown method for the entire questionnaire, was 0.82, and using the Guttman method, it was 0.80.

King's Spiritual Intelligence Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by King in 2007 and consists of 24 questions that measure four components, including existential thinking, transcendental awareness, expansion of the state of consciousness, and the production of personal meaning. Subjects record their responses to each item on a scale of completely false (zero), false (one), somewhat true (two), very true (three), and completely true (four). Accordingly, the score on this scale can range from 0 to 96, with a high score indicating a high level of spiritual intelligence in individuals. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were reported by King in a study involving 619 students, with an alpha coefficient of 0.95. The alpha coefficients for its subscales were as follows: critical existential thinking was 0.88, creating personal meaning was 0.87, transcendental consciousness was 0.89, and expanding transcendental consciousness was 0.94 [29]. In the study by Raghib et al., its reliability was estimated to be 0.88 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and its content validity was also confirmed [30].

Luthans Psychological Capital Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by Luthans et al. in 2007 to measure psychological capital. It consists of 24 questions and four subscales, including hopefulness, resilience, optimism, and self-efficacy, with each subscale containing six items. The examinee responds to each item on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from completely disagree to completely agree. To obtain a psychological capital score, the score for each subscale is calculated separately, and their sum is considered the total psychological capital score. Low or high scores indicate the level of psychological capital of the individual. In the study by Youssef & Luthans, Cronbach’s alpha was obtained for each subscale (hopefulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism) at 0.88, 0.89, 0.89, and 0.89, respectively [31]. The reliability of the questionnaire has also been reported in Iran by Bahadri Khosrowshahi et al. [32], based on a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ)

This questionnaire was developed by Garnefski & Kraaij to measure cognitive regulation strategies. It is a self-report instrument consisting of 36 questions that are scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to always (5). The minimum possible score is 36, and the maximum is 180. A higher score indicates a greater use of that cognitive strategy by the individual [33]. Cognitive strategies for emotion regulation are divided into two general categories: adaptive (compromised) and maladaptive (non-compromised) strategies. The subscales of trivialization, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, acceptance, and refocusing on planning constitute adaptive strategies, while the subscales of self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing constitute maladaptive strategies. The alpha coefficient for the subscales of this questionnaire was reported by Garnefski et al. to range from 0.71 to 0.81 [34]. In Iran, the results of the retest for the subscales of this questionnaire ranged from 0.75 to 0.88 [35].

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation. To examine the main hypotheses and their subscales, the Pearson correlation coefficient, regression analysis, and path analysis were conducted using IMOS software.

Findings

A total of 253 children of veterans (129 females and 124 males) participated, with a mean age of 30.56±7.49 years. Among the participants, 112 (44.3%) were single, and 141 (55.7%) were married. The education levels of the participants were as follows: 44 participants (17.4%) had a diploma or less, 13 participants (5.1%) held a post-diploma degree, 107 participants (42.3%) had a bachelor’s degree, 73 participants (28.9%) had a master’s degree, and 16 participants (6.3%) had a PhD. The injury levels of the veterans were categorized as follows: less than 25% for 148 participants (58.5%), 26 to 40% for 62 participants (24.5%), and more than 40% for 43 participants.

The direction of the correlation between the parameters was as expected and aligned with the relevant theories (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean values and correlation coefficients between research parameters

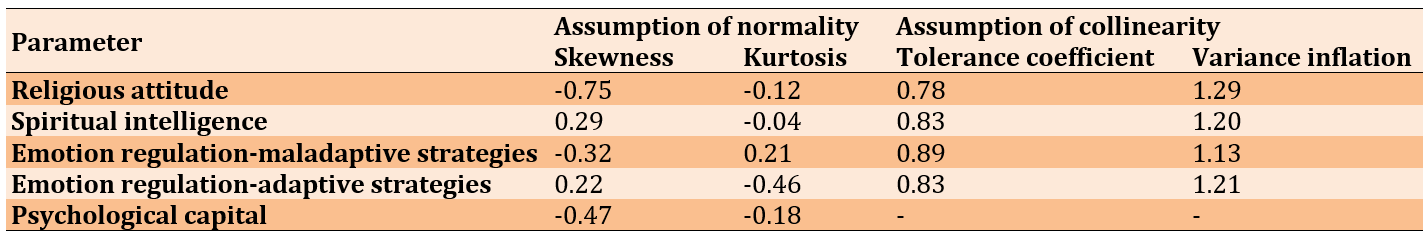

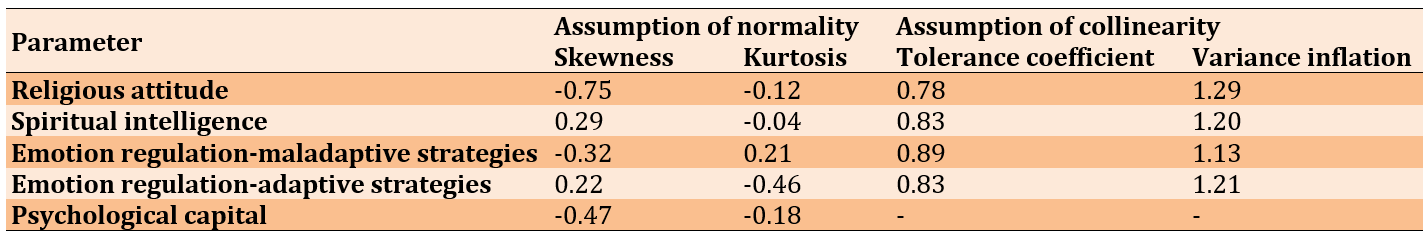

To evaluate the assumption of normal distribution of univariate data, the kurtosis and skewness of the parameters were asssessed. Additionally, to evaluate the assumption of collinearity, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance coefficient were examined (Table 2).

Table 2. Assessing the assumptions of normality and collinearity

The values of kurtosis and skewness for all components were within the range of ±2. This finding indicates that the assumption of normal distribution of univariate data was valid. It can also be stated that the assumption of collinearity was valid among the data, as the tolerance coefficient values of the predictor variables were greater than 0.1 and the VIF values for each of them were less than 10. A tolerance coefficient less than 0.1 and a VIF value higher than ten indicates that the assumption of collinearity is not met. To evaluate whether the assumption of normal distribution of multivariate data is valid, the analysis of information related to the “Mahalanobis distance” was utilized. The skewness and kurtosis values of the aforementioned data were obtained as 1.13 and 0.87, respectively, indicating that the skewness and kurtosis index of that data was within the range of ±2, which confirms that the assumption of normal distribution of multivariate data was valid. Finally, to assess the homogeneity of variances, the scatter diagram of the standardized error variances was examined, and the evaluations showed that this assumption was also valid in the data.

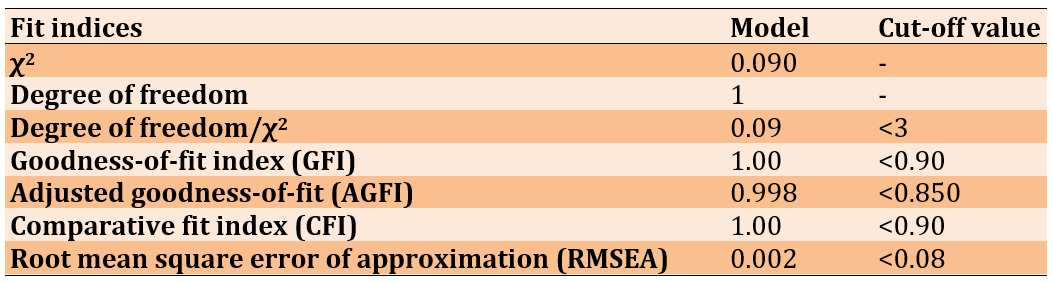

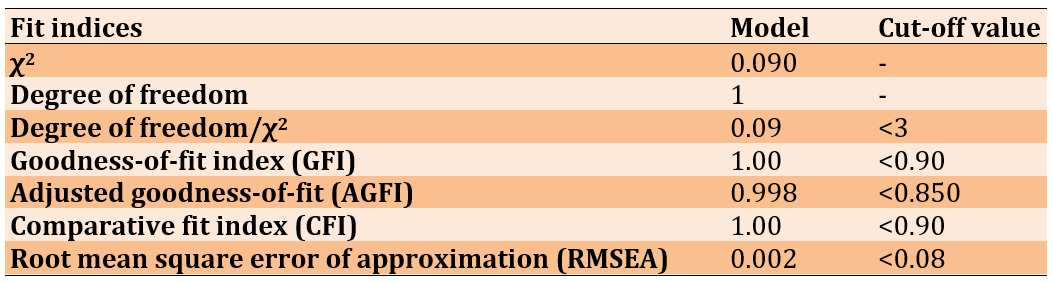

The fit of the model to the collected data was examined using the path analysis method with AMOS 24.0 software and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation (Table 3). All fit indices from the path analysis indicated an acceptable fit of the model to the collected data.

Table 3. Model fit indices

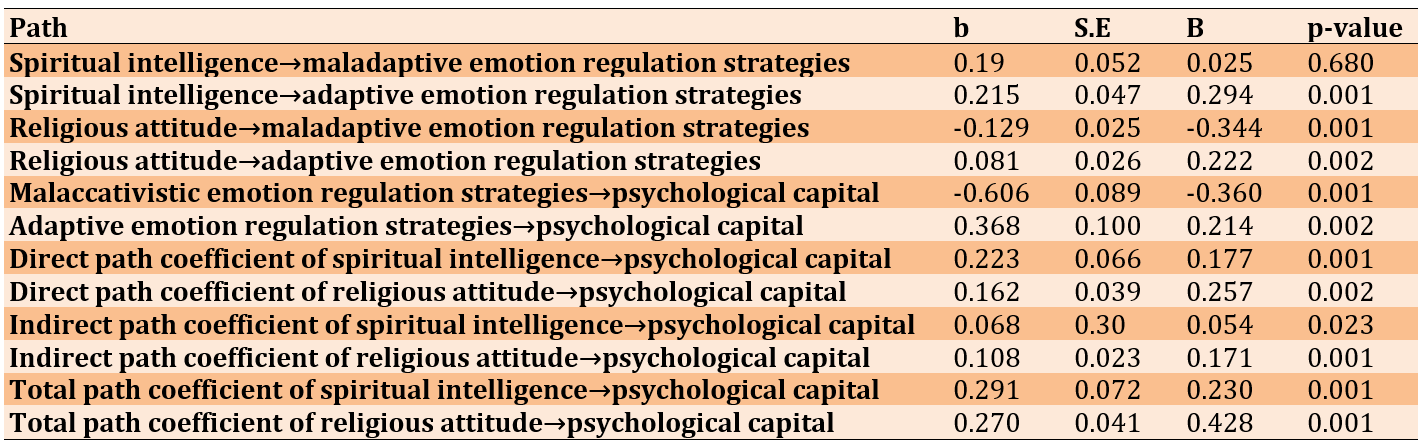

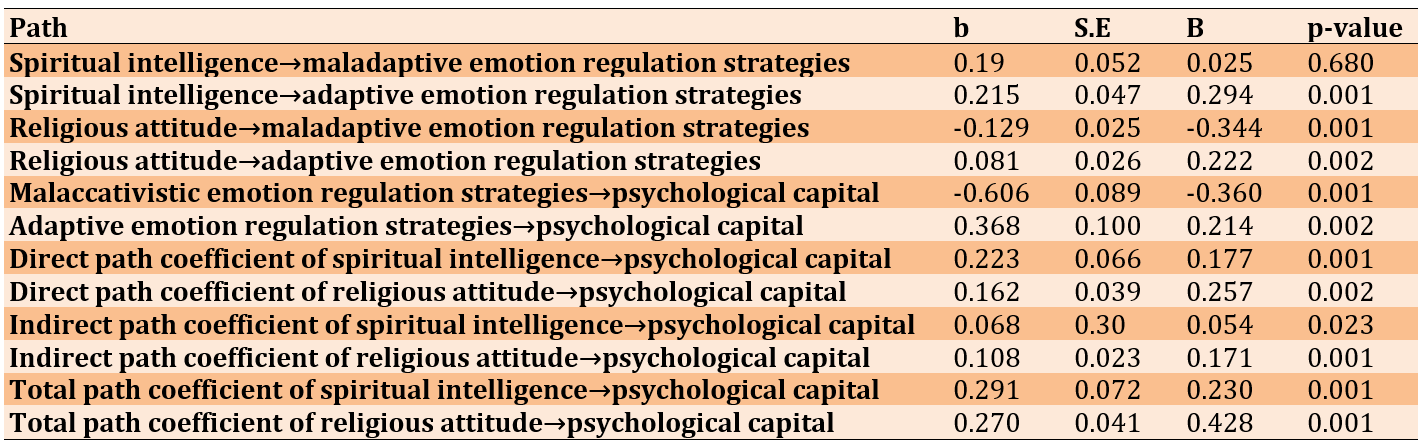

The path coefficients for total spiritual intelligence (p=0.001, β=0.230) and religious attitude (p=0.001, β=0.428) with psychological capital were positive and significant. The path coefficient for adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with psychological capital (p=0.001, β=0.214) was positive, while the path coefficient for maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.360) was negative and significant. The indirect path coefficients for spiritual intelligence (p=0.023, β=0.054) and religious attitude (p=0.001, β=0.171) with psychological capital were both positive and significant. These findings indicate that cognitive emotion regulation strategies mediate the relationship between spiritual intelligence and religious attitude with psychological capital in a positive and significant manner. Using Baron and Kenny’s formula, the indirect path coefficient between spiritual intelligence and psychological capital through adaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=0.061) was positive and significant. In contrast, the indirect path coefficient between these two variables through maladaptive strategies was not significant. Additionally, using this formula, the indirect path coefficients between religious attitude and psychological capital through adaptive strategies (p=0.019, β=0.046) and through maladaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=0.122) of cognitive emotion regulation were both positive and significant. Therefore, both adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively and significantly mediated the relationship between religious attitude and psychological capital in children of veterans. The results also indicated that adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, unlike maladaptive strategies, mediated the relationship between spiritual intelligence and psychological capital in children of veterans (Table 4).

Table 4. Path coefficients of the model

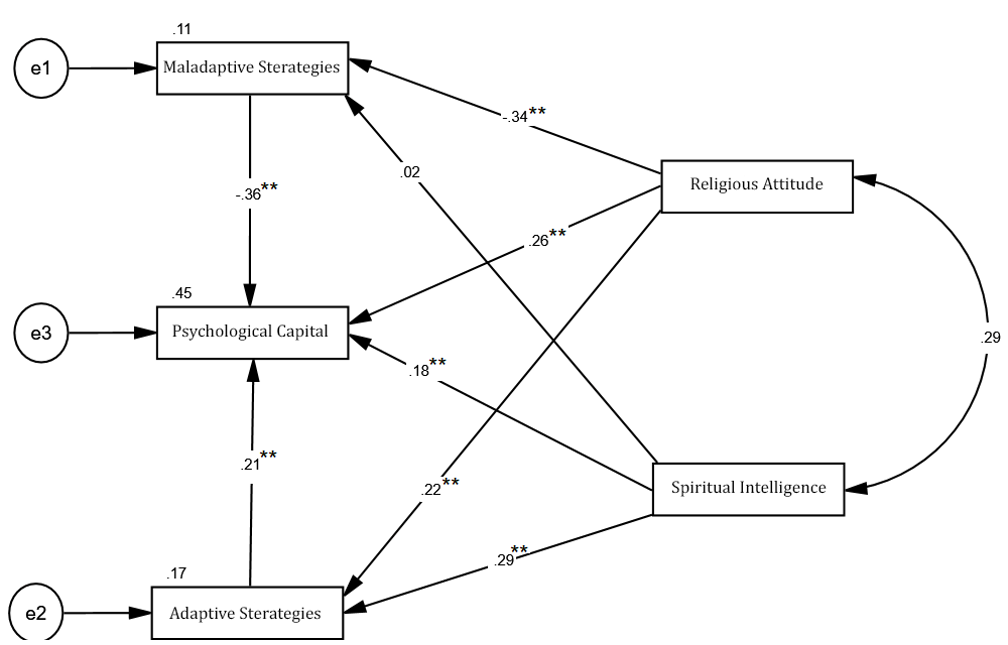

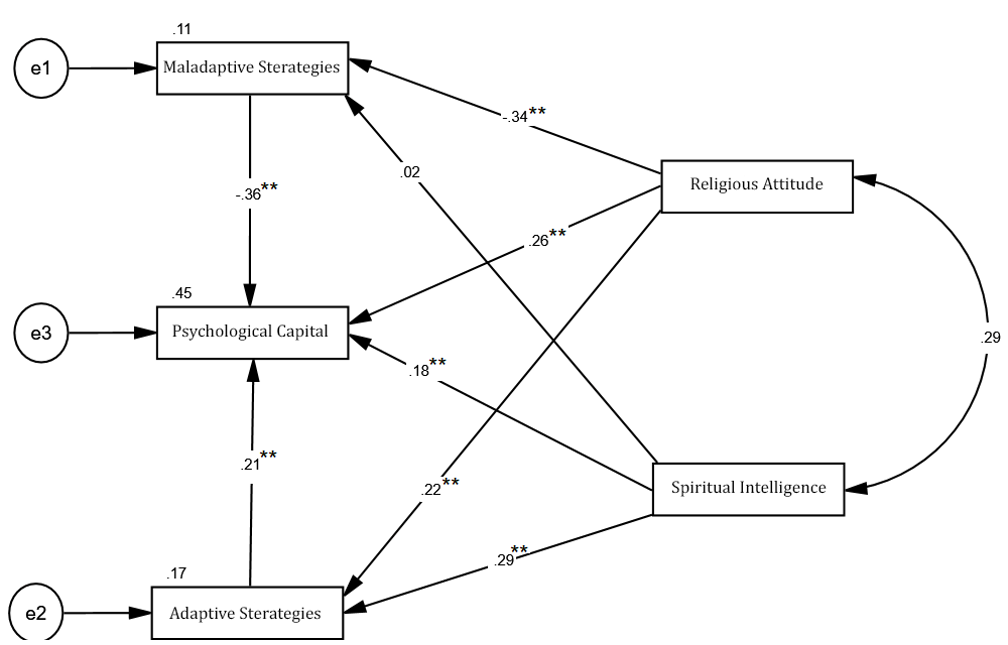

Figure 1. Standard parameters in the structural model of the research

The sum of squared multiple correlations for the psychological capital variable was equal to 0.45. Accordingly, spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explained a total of 45% of the variance in psychological capital among children of veterans (Figure 1).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in explaining the causal relationships between religious attitude and spiritual intelligence with psychological capital in children of veterans. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively and significantly mediated the relationship between spiritual intelligence and religious attitude with psychological capital. The indirect path coefficient between religious attitude, spiritual intelligence, and psychological capital through adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies was positive and significant. Spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explained psychological capital in children of veterans. These findings are consistent with those of other studies [16, 18, 20, 26, 27]. In consistent studies, the effective roles of spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive regulation in promoting health, mental well-being, and increasing quality of life have been emphasized, ultimately leading to increased self-esteem, stress control, and tolerance of psychological pressure.

In explaining this finding, it can be stated that emotion regulation affects the internal and external processes of an individual’s response to the control, monitoring, evaluation, and adjustment of emotional and behavioral interactions, particularly transient characteristics. In other words, emotion regulation can be conscious or unconscious, transient or permanent, and behavioral or cognitive; thus, it can be observed in both behavior and emotion. Additionally, each of the variables of religious attitude and spiritual intelligence can independently predict psychological capital. Religious attitude is one of the most important influential elements in human life because it, through dominant will and by establishing behavioral frameworks, seeks to ensure that individuals derive the best and most benefit from their intentions. Spiritual intelligence, on the other hand, encompasses a set of psychological capacities that contribute to the consciousness of the children of veterans and, while integrating and harmonizing their mental functions and superior aspects of existence, leads them to deep existential reflection, increased meaning, recognition of a superior self, and mastery of their spiritual characteristics. According to Garnefski & Kraaij, cognitive emotion regulation, as a form of social intelligence, is effective in five areas: Self-awareness, self-control, self-motivation, social awareness, and relationship regulation [23].

On the other hand, psychological capital is one of the most fundamental constructs that can help individuals live, adapt, and respond to adverse conditions. Adaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation positively predicted psychological capital in children of veterans, while maladaptive strategies negatively and significantly predicted it, which is consistent with other studies [26-28]. Therefore, when children of veterans use adaptive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital increases, whereas the use of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies leads to a decrease in their psychological capital. Based on this, it can be concluded that adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies significantly mediate the relationship with psychological capital in children of veterans.

In explaining this finding, it can be stated that emotions and their manifestations are among the issues that people engage with on a daily basis. Emotion regulation, as a concept, is based on awareness and understanding of emotions, acceptance of emotions, the ability to control impulsive behaviors, and behaving in accordance with desired goals in order to achieve personal objectives and meet situational demands. In a study on the relationship between levels of psychological well-being and self-esteem, perceived general self-efficacy, Akfirat showed that self-esteem, general self-efficacy, level of hope, and positive reappraisal (one of the cognitive emotion regulation strategies) significantly predict psychological well-being [36]. Cognitive emotion regulation, which is considered a mediating variable, also helps individuals regulate negative arousal and emotions. Mouatsou & Koutra found that effective emotion regulation can enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, enables individuals to respond adaptively to stress [26].

In summary, this study provided deep insight into the relationship between religious attitude, spiritual intelligence, cognitive emotion regulation, and psychological capital. It highlights the mechanisms by which cognitive emotion regulation affects the components of psychological capital, including self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, each of which is a positive construct with significant psychological value and performance. Additionally, when children of veterans aged 18 to 40 use more adaptive or fewer maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital increases. It also appears that spiritual intelligence and religious attitude have directly and indirectly enhanced the use of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies in relation to psychological capital.

Like other studies, this study has limitations. First, all data in this study were collected through self-reported measures. Second, this study was based on a sample of children of veterans living in Tehran, which limits the generalizability of the results.

To address this issue, it is recommended to utilize multiple assessment methods, conduct research at different times, and include larger and more diverse samples. Additionally, future studies should explore other psychological variables and cognitive emotion regulation, examining their effects on psychological capital. This research could be beneficial for counselors, clinical specialists, and others involved in the psychological treatment of veterans and their children.

Conclusion

Spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explain psychological capital in children of veterans.

Acknowledgments: This article is taken from Mohammad Sadegh Elahian's doctoral dissertation. We would like to thank and express our appreciation to all the individuals who cooperated and assisted in this research, as well as to the respected officials of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation, the valuable veterans who are the pride of Iran, and the children of veterans who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The ethics code for this research was issued under number ir.essar.rec.1401.008 with the permission of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation. All participants were assured that their information would remain completely confidential during the testing phase.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Elahian MS (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Rezakhani S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Dokanehifard F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study received no funding.

War-related trauma not only creates challenges for veterans, but it also indirectly affects their families and children, who experience psychological stress and may exhibit symptoms similar to those of their fathers [1, 2]. Secondary traumatic stress refers to the transmission of symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder from an individual who has been directly exposed to a traumatic event to another individual with whom they have close and ongoing contact [3]. In this context, the systematic secondary trauma model theory suggests that when a survivor of primary trauma (the veteran) exhibits trauma symptoms or low levels of functioning within the family system, a systematic response occurs. This response increases the likelihood of developing secondary traumatic stress symptoms in the spouse and family and refers to changes in the survivor’s beliefs about themselves, others, and the external world [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to address the various emotional and psychological issues faced by these individuals [5].

One of the most fundamental structures for the life and adaptation of veterans in response to adverse conditions is the application of a positive psychology approach. A key component of positive psychology is psychological capital, which is regarded as one of the most important characteristics for individuals’ adaptation to challenging circumstances and for improving their quality of life [6]. According to Luthans and Youssef, psychological capital comprises four constructs: hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Each of these can be viewed as a positive psychological capacity with the potential for growth and a significant relationship to performance outcomes [7]. Possessing psychological capital enables individuals to cope more effectively with stressful situations, experience less tension, demonstrate greater resilience in the face of challenges, maintain a clear self-perception, and be less affected by daily events [8].

Psychological capital predicts life satisfaction and flourishing [9], as well as health-promoting behaviors [10]. Additionally, the components of psychological capital have a significant relationship with post-traumatic growth [11, 12]. Cognitive reappraisal and positive psychological capital moderate the relationship between perceived stress and depression, significantly inhibiting depression in individuals with both high and low stress levels [13].

Spiritual intelligence is regarded as one of the effective variables for addressing the problems and tensions faced by the children of veterans. The effects of spiritual intelligence are extensive and encompass a wide range of human behavior. According to King, spiritual intelligence comprises a set of mental adaptive capacities that contribute to consciousness and, by integrating and adapting mental functions and higher aspects of existence, leads individuals to profound existential outcomes, enhancing meaning, recognizing a higher self, and mastering spiritual states [14]. Spiritual intelligence regulates the emotional domain [15], improves mental health [16], alleviates alexithymia, and promotes integrated self-awareness [17].

On the other hand, another issue concerning veterans and their families is their religious attitude. It appears that individuals who participated in the war have a high level of religious attitude. In the study by Kanani et al., it was demonstrated that religiosity and adherence to religious principles can positively influence various aspects of the quality of life of veterans [18]. Additionally, the results of another study indicated that the father-child relationship and the religious attitudes of students play an important and fundamental role in their social adaptation [19]. Based on these findings, religion plays a significant role in preventing the occurrence of diseases [20], promoting the psychological well-being of veterans’ spouses [21], and also impacting subjective well-being [22].

Another crucial and sensitive intrapersonal factor affecting interpersonal relationships in the children of veterans is cognitive emotion regulation. Javadpour et al. consider cognitive emotion regulation a type of social intelligence and have summarized it into five domains: Self-awareness, self-control, self-motivation, social awareness, and relationship regulation [23]. Cognitive emotion regulation is a means of understanding how an individual can organize their attention and take strategic and assertive actions to solve problems [24]. In other words, emotion regulation encompasses conscious or unconscious cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies used to maintain, increase, or decrease an emotion [25]. In this context, research findings indicate that effective emotion regulation can enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, enables individuals to respond adaptively to stress [26]. Additionally, people with higher emotion regulation have a greater ability to tolerate distress and are less impulsive [27]. Guo highlighted the special role of the dimensions of emotion regulation in relation to psychological capital and cognitive resilience [28].

Our country, a victim of war, has been extensively researched over the past half-century regarding the direct psychological impact of experiencing trauma. However, much less research has focused on the secondary effects of living with someone who has suffered from war trauma, as their children and families are indirectly affected by this trauma. Children of veterans were raised by fathers who experienced injuries and traumas from the war, and, conversely, the veterans’ attitudes toward life influence their communication patterns with their children. Accordingly, the present study aimed to investigate the causal relationships between religious attitude and spiritual intelligence, with psychological capital in children of veterans, while considering the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation.

Instrument and Methods

This research was fundamental in terms of its purpose and descriptive (correlational) in terms of the data collection method, utilizing structural equation model analysis. The research population consisted of all children of veterans living in Tehran, aged between 18 and 40. Their fathers were members of the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs in Tehran between April 2022 and September 2022. According to statistical information from the Foundation, the number of individuals was reported as 86,642. The sample size, based on Michel (1993, cited in Meyer et al., 2006), was estimated at 247 people and was increased to 260 to account for potential attrition. Consequently, 260 children of Iranian and Iraqi veterans completed the questionnaires online. It is worth noting that after eliminating seven incomplete questionnaires, 253 questionnaires were analyzed. Since the complete list of individuals in the research population was not available to the researcher, a convenience sampling method was employed. Four questionnaires were used in this study.

Religious Attitude Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by Khodayari Fard et al. in 2013 to measure religious attitudes and consists of 40 questions. It assesses four subscales: Religious belief, religious emotions, religious behavior, and social pretense. The subjects’ scores in response to each question are determined on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from always (5) to never (0). The total score for this questionnaire ranges from 40 to 200. A high score on each of the subscales indicates a person’s elevated level of attitude and beliefs regarding religious matters. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire have been reported as 0.96 and 0.94 in two studies [29]. The reliability coefficient obtained through the test-retest method was 0.91, while the split-half reliability, using the Spearman-Brown method for the entire questionnaire, was 0.82, and using the Guttman method, it was 0.80.

King's Spiritual Intelligence Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by King in 2007 and consists of 24 questions that measure four components, including existential thinking, transcendental awareness, expansion of the state of consciousness, and the production of personal meaning. Subjects record their responses to each item on a scale of completely false (zero), false (one), somewhat true (two), very true (three), and completely true (four). Accordingly, the score on this scale can range from 0 to 96, with a high score indicating a high level of spiritual intelligence in individuals. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were reported by King in a study involving 619 students, with an alpha coefficient of 0.95. The alpha coefficients for its subscales were as follows: critical existential thinking was 0.88, creating personal meaning was 0.87, transcendental consciousness was 0.89, and expanding transcendental consciousness was 0.94 [29]. In the study by Raghib et al., its reliability was estimated to be 0.88 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and its content validity was also confirmed [30].

Luthans Psychological Capital Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by Luthans et al. in 2007 to measure psychological capital. It consists of 24 questions and four subscales, including hopefulness, resilience, optimism, and self-efficacy, with each subscale containing six items. The examinee responds to each item on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from completely disagree to completely agree. To obtain a psychological capital score, the score for each subscale is calculated separately, and their sum is considered the total psychological capital score. Low or high scores indicate the level of psychological capital of the individual. In the study by Youssef & Luthans, Cronbach’s alpha was obtained for each subscale (hopefulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism) at 0.88, 0.89, 0.89, and 0.89, respectively [31]. The reliability of the questionnaire has also been reported in Iran by Bahadri Khosrowshahi et al. [32], based on a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ)

This questionnaire was developed by Garnefski & Kraaij to measure cognitive regulation strategies. It is a self-report instrument consisting of 36 questions that are scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to always (5). The minimum possible score is 36, and the maximum is 180. A higher score indicates a greater use of that cognitive strategy by the individual [33]. Cognitive strategies for emotion regulation are divided into two general categories: adaptive (compromised) and maladaptive (non-compromised) strategies. The subscales of trivialization, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, acceptance, and refocusing on planning constitute adaptive strategies, while the subscales of self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing constitute maladaptive strategies. The alpha coefficient for the subscales of this questionnaire was reported by Garnefski et al. to range from 0.71 to 0.81 [34]. In Iran, the results of the retest for the subscales of this questionnaire ranged from 0.75 to 0.88 [35].

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation. To examine the main hypotheses and their subscales, the Pearson correlation coefficient, regression analysis, and path analysis were conducted using IMOS software.

Findings

A total of 253 children of veterans (129 females and 124 males) participated, with a mean age of 30.56±7.49 years. Among the participants, 112 (44.3%) were single, and 141 (55.7%) were married. The education levels of the participants were as follows: 44 participants (17.4%) had a diploma or less, 13 participants (5.1%) held a post-diploma degree, 107 participants (42.3%) had a bachelor’s degree, 73 participants (28.9%) had a master’s degree, and 16 participants (6.3%) had a PhD. The injury levels of the veterans were categorized as follows: less than 25% for 148 participants (58.5%), 26 to 40% for 62 participants (24.5%), and more than 40% for 43 participants.

The direction of the correlation between the parameters was as expected and aligned with the relevant theories (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean values and correlation coefficients between research parameters

To evaluate the assumption of normal distribution of univariate data, the kurtosis and skewness of the parameters were asssessed. Additionally, to evaluate the assumption of collinearity, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance coefficient were examined (Table 2).

Table 2. Assessing the assumptions of normality and collinearity

The values of kurtosis and skewness for all components were within the range of ±2. This finding indicates that the assumption of normal distribution of univariate data was valid. It can also be stated that the assumption of collinearity was valid among the data, as the tolerance coefficient values of the predictor variables were greater than 0.1 and the VIF values for each of them were less than 10. A tolerance coefficient less than 0.1 and a VIF value higher than ten indicates that the assumption of collinearity is not met. To evaluate whether the assumption of normal distribution of multivariate data is valid, the analysis of information related to the “Mahalanobis distance” was utilized. The skewness and kurtosis values of the aforementioned data were obtained as 1.13 and 0.87, respectively, indicating that the skewness and kurtosis index of that data was within the range of ±2, which confirms that the assumption of normal distribution of multivariate data was valid. Finally, to assess the homogeneity of variances, the scatter diagram of the standardized error variances was examined, and the evaluations showed that this assumption was also valid in the data.

The fit of the model to the collected data was examined using the path analysis method with AMOS 24.0 software and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation (Table 3). All fit indices from the path analysis indicated an acceptable fit of the model to the collected data.

Table 3. Model fit indices

The path coefficients for total spiritual intelligence (p=0.001, β=0.230) and religious attitude (p=0.001, β=0.428) with psychological capital were positive and significant. The path coefficient for adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with psychological capital (p=0.001, β=0.214) was positive, while the path coefficient for maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.360) was negative and significant. The indirect path coefficients for spiritual intelligence (p=0.023, β=0.054) and religious attitude (p=0.001, β=0.171) with psychological capital were both positive and significant. These findings indicate that cognitive emotion regulation strategies mediate the relationship between spiritual intelligence and religious attitude with psychological capital in a positive and significant manner. Using Baron and Kenny’s formula, the indirect path coefficient between spiritual intelligence and psychological capital through adaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=0.061) was positive and significant. In contrast, the indirect path coefficient between these two variables through maladaptive strategies was not significant. Additionally, using this formula, the indirect path coefficients between religious attitude and psychological capital through adaptive strategies (p=0.019, β=0.046) and through maladaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=0.122) of cognitive emotion regulation were both positive and significant. Therefore, both adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively and significantly mediated the relationship between religious attitude and psychological capital in children of veterans. The results also indicated that adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, unlike maladaptive strategies, mediated the relationship between spiritual intelligence and psychological capital in children of veterans (Table 4).

Table 4. Path coefficients of the model

Figure 1. Standard parameters in the structural model of the research

The sum of squared multiple correlations for the psychological capital variable was equal to 0.45. Accordingly, spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explained a total of 45% of the variance in psychological capital among children of veterans (Figure 1).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in explaining the causal relationships between religious attitude and spiritual intelligence with psychological capital in children of veterans. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively and significantly mediated the relationship between spiritual intelligence and religious attitude with psychological capital. The indirect path coefficient between religious attitude, spiritual intelligence, and psychological capital through adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies was positive and significant. Spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explained psychological capital in children of veterans. These findings are consistent with those of other studies [16, 18, 20, 26, 27]. In consistent studies, the effective roles of spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive regulation in promoting health, mental well-being, and increasing quality of life have been emphasized, ultimately leading to increased self-esteem, stress control, and tolerance of psychological pressure.

In explaining this finding, it can be stated that emotion regulation affects the internal and external processes of an individual’s response to the control, monitoring, evaluation, and adjustment of emotional and behavioral interactions, particularly transient characteristics. In other words, emotion regulation can be conscious or unconscious, transient or permanent, and behavioral or cognitive; thus, it can be observed in both behavior and emotion. Additionally, each of the variables of religious attitude and spiritual intelligence can independently predict psychological capital. Religious attitude is one of the most important influential elements in human life because it, through dominant will and by establishing behavioral frameworks, seeks to ensure that individuals derive the best and most benefit from their intentions. Spiritual intelligence, on the other hand, encompasses a set of psychological capacities that contribute to the consciousness of the children of veterans and, while integrating and harmonizing their mental functions and superior aspects of existence, leads them to deep existential reflection, increased meaning, recognition of a superior self, and mastery of their spiritual characteristics. According to Garnefski & Kraaij, cognitive emotion regulation, as a form of social intelligence, is effective in five areas: Self-awareness, self-control, self-motivation, social awareness, and relationship regulation [23].

On the other hand, psychological capital is one of the most fundamental constructs that can help individuals live, adapt, and respond to adverse conditions. Adaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation positively predicted psychological capital in children of veterans, while maladaptive strategies negatively and significantly predicted it, which is consistent with other studies [26-28]. Therefore, when children of veterans use adaptive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital increases, whereas the use of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies leads to a decrease in their psychological capital. Based on this, it can be concluded that adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies significantly mediate the relationship with psychological capital in children of veterans.

In explaining this finding, it can be stated that emotions and their manifestations are among the issues that people engage with on a daily basis. Emotion regulation, as a concept, is based on awareness and understanding of emotions, acceptance of emotions, the ability to control impulsive behaviors, and behaving in accordance with desired goals in order to achieve personal objectives and meet situational demands. In a study on the relationship between levels of psychological well-being and self-esteem, perceived general self-efficacy, Akfirat showed that self-esteem, general self-efficacy, level of hope, and positive reappraisal (one of the cognitive emotion regulation strategies) significantly predict psychological well-being [36]. Cognitive emotion regulation, which is considered a mediating variable, also helps individuals regulate negative arousal and emotions. Mouatsou & Koutra found that effective emotion regulation can enhance self-esteem, which, in turn, enables individuals to respond adaptively to stress [26].

In summary, this study provided deep insight into the relationship between religious attitude, spiritual intelligence, cognitive emotion regulation, and psychological capital. It highlights the mechanisms by which cognitive emotion regulation affects the components of psychological capital, including self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, each of which is a positive construct with significant psychological value and performance. Additionally, when children of veterans aged 18 to 40 use more adaptive or fewer maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital increases. It also appears that spiritual intelligence and religious attitude have directly and indirectly enhanced the use of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies in relation to psychological capital.

Like other studies, this study has limitations. First, all data in this study were collected through self-reported measures. Second, this study was based on a sample of children of veterans living in Tehran, which limits the generalizability of the results.

To address this issue, it is recommended to utilize multiple assessment methods, conduct research at different times, and include larger and more diverse samples. Additionally, future studies should explore other psychological variables and cognitive emotion regulation, examining their effects on psychological capital. This research could be beneficial for counselors, clinical specialists, and others involved in the psychological treatment of veterans and their children.

Conclusion

Spiritual intelligence, religious attitude, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explain psychological capital in children of veterans.

Acknowledgments: This article is taken from Mohammad Sadegh Elahian's doctoral dissertation. We would like to thank and express our appreciation to all the individuals who cooperated and assisted in this research, as well as to the respected officials of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation, the valuable veterans who are the pride of Iran, and the children of veterans who participated in this study.

Ethical Permissions: The ethics code for this research was issued under number ir.essar.rec.1401.008 with the permission of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation. All participants were assured that their information would remain completely confidential during the testing phase.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Elahian MS (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Rezakhani S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (50%); Dokanehifard F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: This study received no funding.

Keywords:

References

1. Bazoolnejad M, Robatmili S. Correlation of parental perception and its components with attachment style and tendency to communicate with the opposite sex in veterans' daughters. Iran J War Public Health. 2018;10(2):91-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijwph.10.2.91]

2. Fakhri Z, Danesh I, Shahidi S, Seliminia AR. Quality of value system and self-efficacy beliefs in children with veteran and non-veteran fathers. J Appl Psychol. 2013;6(4):25-42. [Persian] [Link]

3. Rauvola RS, Vega DM, Lavigne KN. Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization: A qualitative review and research agenda. Occup Health Sci. 2019;3(3):297-336. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s41542-019-00045-1]

4. Johnson RA, Albright DL, Marzolf JR, Bibbo JL, Yaglom HD, Crowder SM, et al. Effects of therapeutic horseback riding on post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. Mil Med Res. 2018;5(1):3. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40779-018-0149-6]

5. Rezapour Mirsaleh Y, Zakeri F, Amini R, Eslamifard M. A study of the relationship between psychological acceptance and self-compassion and attitude to seeking psychological help in the children of disabled veterans. 2021;12(45):7-19. [Persian] [Link]

6. Etikariena A. The effect of psychological capital as a mediator variable on the relationship between work happiness and innovative work behavior. In: Diversity in unity: Perspectives from psychology and behavioral sciences. London: Routledge; 2017. pp. 379-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1201/9781315225302-46]

7. Luthans F, Youssef CM. Emerging positive organizational behavior. J Manage. 2007;33(3):321-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0149206307300814]

8. Azimi D, Gadimi S, Khazan K, Dargahi S. The role of psychological capitals and academic motivation in academic vitality and decisional procrastination in nursing students. J Med Educ Dev. 2017;12(3):147-57. [Persian] [Link]

9. Santisi G, Lodi E, Magnano P, Zarbo R, Zammitti A. Relationship between psychological capital and quality of life: The role of courage. Sustainability. 2020;12(13):5238. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/su12135238]

10. Bakhshi N, Pashang S, Jafari N, Ghorban-Shiroudi S. Developing a model of psychological well-being in elderly based on life expectancy through mediation of death anxiety. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2020;8(3):283-93. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijhehp.8.3.283]

11. Weber MC, Pavlacic JM, Gawlik EA, Schulenberg SE, Buchanan EM. Modeling resilience, meaning in life, posttraumatic growth, and disaster preparedness with two samples of tornado survivors. Traumatology. 2020;26(3):266-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/trm0000210]

12. Boullion GQ, Pavlacic JM, Schulenberg SE, Buchanan EM, Steger MF. Meaning, social support, and resilience as predictors of posttraumatic growth: A study of the Louisiana flooding of August 2016. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90(5):578-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/ort0000464]

13. Liu Y, Yu H, Shi Y, Ma C. The effect of perceived stress on depression in college students: The role of emotion regulation and positive psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1110798. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1110798]

14. King DB. Personal meaning production as a component of spiritual intelligence. Int J Existent Psychol Psychother. 2010;3(1):1-5. [Link]

15. Nirimani M, Asgharpour I. Predicting changes in alexithymia of addicts from their spiritual intelligence. J Fundam Ment Health. 2014;16(1):3-11. [Persian] [Link]

16. Shateri K, Hayat AA, Jayervand H. The relationship between mental health and spiritual intelligence among primary school teachers. Int J Sch Health. 2019;6(1):1-6. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/intjsh.74031]

17. Mansuri B, Hoseinifar J. The effectiveness of spiritual intelligence training on social adjustment, alexithymia and integrative self-knowledge in divorce students. J Sch Psychol. 2020;3(9):234-58. [Persian] [Link]

18. Kanani Z, Poursadooghi A, Nejati S, Adib Sareshki N. The relationship between religious belief and quality of life in veterans amputations. J Mil Psychol. 2015;5(20):5-15. [Persian] [Link]

19. Khodayari Fard M. Comparing the relationship between religious attitude and father-child relationship with social adjustment in veteran and normal children of Tehran. J Psychol. 2004;8(4):372. [Persian] [Link]

20. Karimi N, Mousavi S, Falah-Neudehi M. The prediction of psychological well-being based on the components of religious attitude and self-esteem among the elderly in Ahvaz, Iran. J Res Relig Health. 2021;6(4):88-100. [Persian] [Link]

21. Jian-Bagheri M, Notarkesh M, Ghammari M. The relationship of religiousness and resilience with psychological well-being in veterans' wives. J Res Relig Health. 2021;7(1):81-94. [Persian] [Link]

22. Mohammadkhani M, Haghighat Sh, Beidaghi F, Bagheri-Panah M. Path analysis model of the relationship between job satisfaction and religious coping styles, spiritual experiences and subjective well-being in Payame Noor University staff. J Res Relig Health. 2021;6(4):18-31. [Link]

23. Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Specificity of relations between adolescents' cognitive emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Cogn Emot. 2018;32(7):1401-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/02699931.2016.1232698]

24. Javadpour M, Rezaee A, Javidi H, Khayyer M. Effectiveness of cognitive emotional regulation training on the impulsivity and peer relationship in high school students: A pilot study. Community Health. 2022;9(2):94-101. [Persian] [Link]

25. Strauss AY, Kivity Y, Huppert JD. Emotion regulation strategies in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Behav Ther. 2019;50(3):659-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2018.10.005]

26. Mouatsou C, Koutra K. Emotion regulation in relation with resilience in emerging adults: The mediating role of self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(2):734-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12144-021-01427-x]

27. Asgari M, Matini A. The effectiveness of emotion regulation training based on gross model in reducing impulsivity in smokers. Couns Cult Psycother. 2020;11(42):205-30. [Persian] [Link]

28. Guo Z, Cui Y, Yang T, Liu X, Lu H, Zhang Y, Zhu X. Network analysis of affect, emotion regulation, psychological capital, and resilience among Chinese males during the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1144420. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1144420]

29. King DB. The spiritual intelligence project. Canada: Trent University; 2007. [Link]

30. Raghib M, Siadat A, Hakimi Nia B, Ahmadi J. Validation of king spiritual intelligence scale (24-SISRI) in students university of Esfahan. Psychol Achiev. 2010;17(1):141-64. [Persian] [Link]

31. Youssef C, Luthans F. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. J Manag. 2007;33(5):774-800. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0149206307305562]

32. Bahadri Khosrowshahi J, Hashemi Nusrat Abad T, Birami M. The relationship between psychological capital and personality traits with job satisfaction in public library librarians in Tabriz. Pajoohande. 2013;17(6):313-9. [Persian] [Link]

33. Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire-development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personal Individ Differ. 2006;41(6):1045-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010]

34. Garnefski N, Van Den Kommer T, Kraaij V, Teerds J, Legerstee J, Onstein E. The relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems: Comparison between a clinical and a non-clinical sample. Eur J Personal. 2002;16(5):403-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/per.458]

35. Basharat MA, Bezazian S. Psychometri properties of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire in a sample of Iranian population. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2015;24(84):61-70. [Link]

36. Akfirat N. Investigation of relationship between psychological well-being, self esteem, perceived general self-efficacy, level of hope and cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Eur J Educ Stud. 2020;7(9). [Link] [DOI:10.46827/ejes.v7i9.3267]