Volume 17, Issue 1 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(1): 9-16 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: 1401008

History

Received: 2024/07/28 | Accepted: 2024/12/19 | Published: 2025/01/10

Received: 2024/07/28 | Accepted: 2024/12/19 | Published: 2025/01/10

How to cite this article

Elahian M, Rezakhani S, Dokanehifard F. Relationship between Early Maladaptive Schemas and Psychological Capital in Children of Veterans; a Psychological Perspective. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (1) :9-16

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1494-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1494-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Counseling, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1135 Views)

Introduction

Children of veterans are exposed to psychological issues and experience symptoms related to their fathers during their time with their parents [1]. Although it is assumed that trauma affects the victim’s relationships with all family members, studies have shown that the relationship between a traumatized veteran and his or her child is often characterized by conflict, control, excessive closeness, and overprotection. This, in turn, may lead to various psychopathological symptoms among the children of veterans, a phenomenon known as “secondary trauma” [2]. Secondary traumatic stress refers to the transmission of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like symptoms from an individual who was directly exposed to a traumatic event to another individual with whom they have close and ongoing contact [3, 4]. Therefore, it is important to address the various emotional and psychological issues faced by these individuals [5].

Today, psychology has moved away from focusing solely on pathology, and the positive psychology approach has also become a central focus for researchers in this field. One of these positive components is the existence of psychological capital, which is considered one of the most important characteristics for individuals’ adaptation to difficult conditions and for enhancing their quality of life [6]. According to Luthans and Youssef, psychological capital is composed of four constructs: hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Each of these can be considered a positive psychological capacity that has the potential to grow and is significantly related to performance outcomes [7]. Having psychological capital enables individuals to cope better with stressful situations, feel less stressed, exhibit high resilience in the face of problems, achieve a clear view of themselves, and be less affected by daily events [8].

Psychological capital predicts problem-solving ability in students [9], health-promoting behaviors in the elderly [10], and life satisfaction as well as marital satisfaction in spouses of veterans [11]. In this regard, cognitive reappraisal and positive psychological capital moderate the relationship between perceived stress and depression, significantly inhibiting depression in individuals with both high and low stress levels [12].

Another crucial and sensitive intrapersonal factor affecting interpersonal relationships in children of veterans is cognitive emotion regulation. Cognitive emotion regulation is very important in life, and one of the most common methods involves the use of cognitive emotion strategies [13, 14]. Cognitive emotion regulation refers to how an individual can organize their attention and achieve strategic and persistent actions to solve problems [15]. In other words, emotion regulation encompasses conscious or unconscious cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies that are used to maintain, increase, or decrease emotions [16].

Garnefski and Kraaij believe that cognitive emotion regulation strategies are cognitive processes that individuals use to cope with stressful situations and manage arousing information. These strategies focus on the cognitive dimension of coping; therefore, thoughts and cognitions play a significant role in the ability to manage, regulate, and control feelings and emotions after experiencing a stressful situation [17]. In this context, effective emotion regulation can strengthen self-esteem, which, in turn, enables individuals to respond adaptively to stress [18]. Guo et al. demonstrated the special role of the dimensions of emotion regulation in relation to psychological capital and cognitive resilience [19]. Emotion regulation has a positive relationship with psychological resilience and may facilitate both emotion-focused and problem-focused coping strategies, thereby promoting psychological resilience [20].

On the other hand, children of veterans have different mental frameworks compared to others in society due to secondary trauma. In this context, a concept called primary maladaptive schemas is proposed. Primary maladaptive schemas can be considered deep and pervasive themes that encompass memories, cognitions, and bodily sensations. These schemas, which are relevant to one’s relationship with oneself and others, can cause dissatisfaction in relationships by creating primary emotional and cognitive barriers [21]. Young has presented a schema model focused on cognitive behavioral problems. According to him, primary maladaptive schemas are deep and pervasive internal patterns formed in childhood or adolescence that persist throughout life, are related to the individual’s relationship with themselves and others, and are highly dysfunctional [22].

Amini and Khoshravesh believe that schemas determine how individuals approach and view themselves, the world, and the future. If schemas are positive, the individual’s perspective will be hopeful and successful; conversely, if schemas are negative, the individual may view themselves as incompetent and worthless, perceive obstacles in facing challenges as impenetrable, and experience failure in every attempt. Such an individual is likely to develop a negative outlook on the world around them and on the future [23]. In this regard, Gorji and Salehi demonstrated that early maladaptive schemas and cognitive emotion regulation strategies can predict resilience and quality of life [24].

The specific geographical and political conditions of our country in the region, the situation in the Middle East, the outbreak of successive wars in this area, and the voluntary presence of individuals with religious convictions calling for the defense of the Shrine of the Innocents (PBUH) contribute to the perception that our country is perpetually involved in conflict. A significant portion of our population is imbued with religious attitudes, which further influences this perception. Most research has focused on the effects of the imposed war from the time it began to the present, and the direct psychological impact of experiencing severe psychological trauma, such as that caused by war, has been thoroughly and comprehensively studied over the past half-century. However, the secondary impact of living with someone who suffers from PTSD has been much less examined. While soldiers and veterans are directly affected by war, their children and families are the indirect victims of these events. Physical trauma can create a ripple effect that impacts not only the victims themselves but also those close to them, particularly their children. Children of veterans are often raised by fathers who carry injuries and traumas from the war, and the veterans’ attitudes toward life are reflected in their communication patterns with their children. Given the significance of this issue, the present study aimed to investigate the causal relationships between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans, with cognitive emotion regulation serving as a mediating factor.

Instrument and methods

This descriptive fundamental research employed structural equation modeling analysis. The research population included children (girls and boys) of veterans residing in Tehran, aged between 18 and 40 years, covered by the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs from April to September 2022, totaling 86,642 individuals. The sample size was estimated to be 247 individuals. The questionnaires were designed using Press Line, and after receiving the questionnaire link, they were sent to the research sample through the Short Message Service Centre in coordination with a phone call from the Call Center of the Veterans Engineering and Medical Sciences Research Institute. Considering the possibility of dropouts, the number of participants was increased to 260. The questionnaires were answered online. After removing seven incomplete questionnaires, 253 questionnaires were analyzed. Since the list of all individuals in the research population was not available to the researcher, the available sampling method was used.

Data collection

Three questionnaires were utilized for data collection.

Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form: This questionnaire was designed by Young et al. to measure 15 schemas across five domains: rejection and abandonment, impaired autonomy and functioning, impaired limitations, other-orientation, and alertness. It consists of 75 questions. Each item of this questionnaire is scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from completely false to completely true (completely false=1, almost false=2, more true than false=3, slightly true=4, almost true=5, completely true=6). Scores above 25 in each subscale indicate a maladaptive schema [25]. Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales in non-clinical populations ranged from 0.50 to 0.82. The validity of the questionnaire has also been reported as satisfactory [26]. The standardization of this questionnaire in a student sample in Iran was calculated using the internal consistency method through Cronbach’s alpha, yielding values of 0.94 for cut-off and exclusion, 0.91 for self-regulation and impaired functioning, 0.87 for other-orientation, 0.88 for alertness, and 0.85 for impaired limitations. The values for women were 0.97, while for men, it was 0.98 [27].

Luthans Psychological Capital Questionnaire: This questionnaire was designed by Luthans et al. in 2007 to measure psychological capital. It consists of 24 questions and four subscales: hopefulness, resilience, optimism, and self-efficacy, with each subscale containing six items. The test taker answers each item on a 6-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). To obtain the psychological capital score, the score for each subscale is calculated separately, and their sum is considered the total psychological capital score. High or low scores indicate the level of psychological capital of the individual [7]. In the study by Youssef & Luthans, Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale (hopefulness, resilience, self-efficacy, optimism) was obtained at 0.88, 0.89, 0.89, and 0.89, respectively [28]. The reliability of the questionnaire has also been reported in Iran by Bahadori Khosroshahi et al. [29], based on a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ): This questionnaire was developed by Garnefski and Kraaij to measure cognitive regulation strategies. It is a self-report instrument consisting of 36 questions that are scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never (one) to always (five). The minimum possible score is 36, and the maximum is 180. A higher score indicates a greater use of that cognitive strategy by the individual [7]. Cognitive strategies for emotion regulation are divided into two general categories: adaptive strategies, which include positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, acceptance, and refocusing on planning, and maladaptive strategies, which include self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing. The alpha coefficient for the subscales of this questionnaire was reported by Garnefski et al. to range from 0.71 to 0.81 [30]. In Iran, the results of the retest of the subscales of this questionnaire, with an interval of one week, ranged from 0.75 to 0.88, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for adaptive strategies was reported to be 0.90, while for maladaptive strategies, it was 0.87 [31].

Data Analysis:

To analyze the data at the descriptive level, the mean and standard deviation were used. To examine the main hypotheses and their subscales, the Pearson correlation coefficient, regression analysis, and path analysis were employed using the AMOS software 24.

Findings

A total of 253 children of veterans (129 women and 124 men), with a mean age of 30.56±7.49 years, participated in this study. Among the participants, 112 (44.3%) were single, and 141 (55.7%) were married. Regarding educational levels, 44 cases (17.4%) had a diploma or less, 13 (5.1%) had a post-diploma, 107 (42.3%) had a bachelor’s degree, 73 (28.9%) had a master’s degree, and 16 (6.3%) held a PhD degree. The level of injury percentage was less than 25% for 148 participants (58.5%), 26 to 40% for 62 cases (24.5%), and more than 40% for the remaining participants. It should be noted that in 193 (participants 76.3%), their parents were injured before their birth (Table 1).

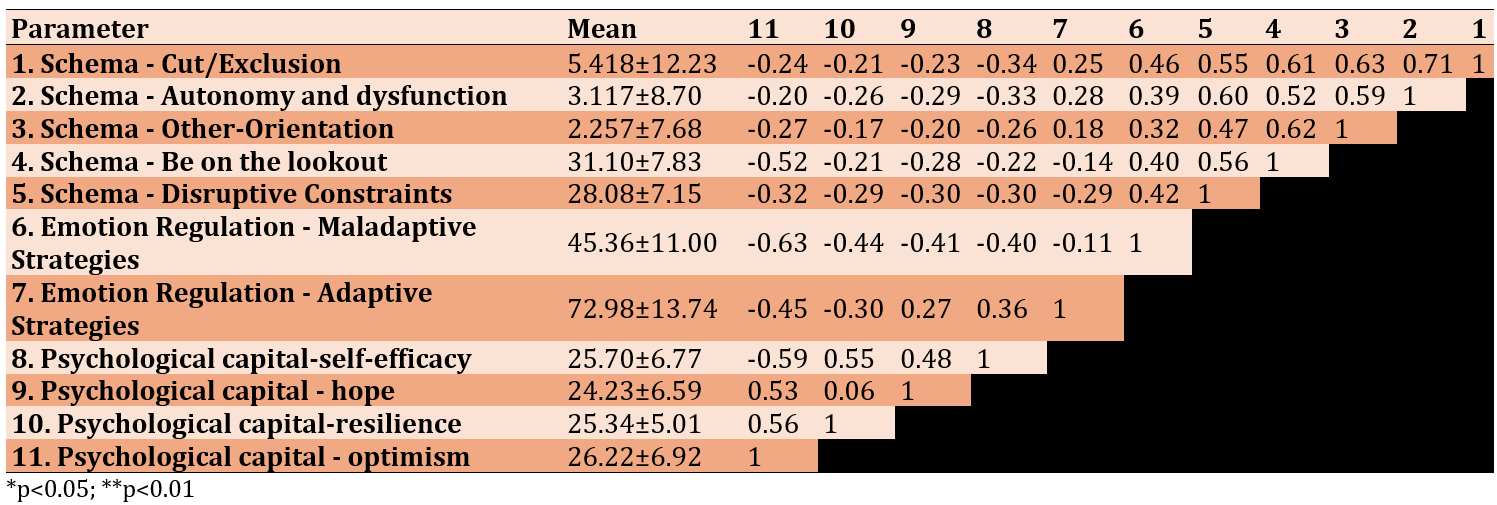

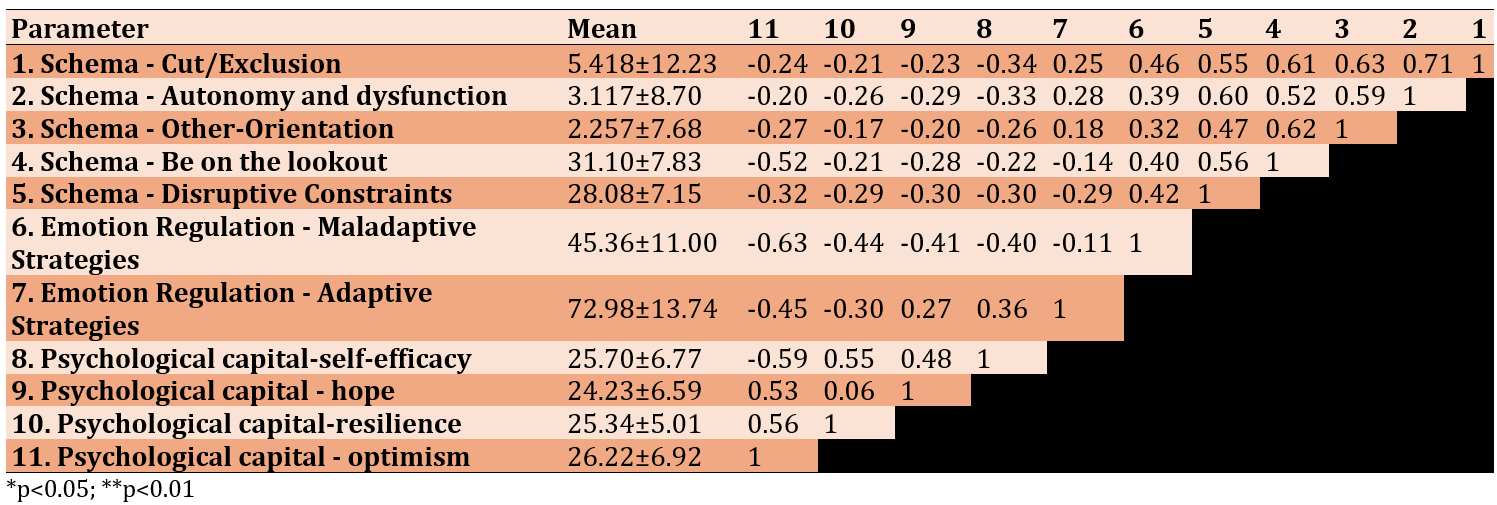

Table 1. Mean values and correlation coefficients between research parameters

To evaluate the assumption of normal distribution of univariate data, the kurtosis and skewness were examined. To assess the assumption of collinearity, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance coefficient were analyzed. To determine whether the assumption of normal distribution of multivariate data is valid, the “Mahalanobis distance” was utilized. The skewness and kurtosis values were obtained as 1.12 and 0.89, respectively were within the range of ±2, supporting the normal distribution of multivariate data. Finally, to evaluate the homogeneity of variances, the scatter plot displaying the standardized error variances was used, and this assumption was also valid.

Model Analysis

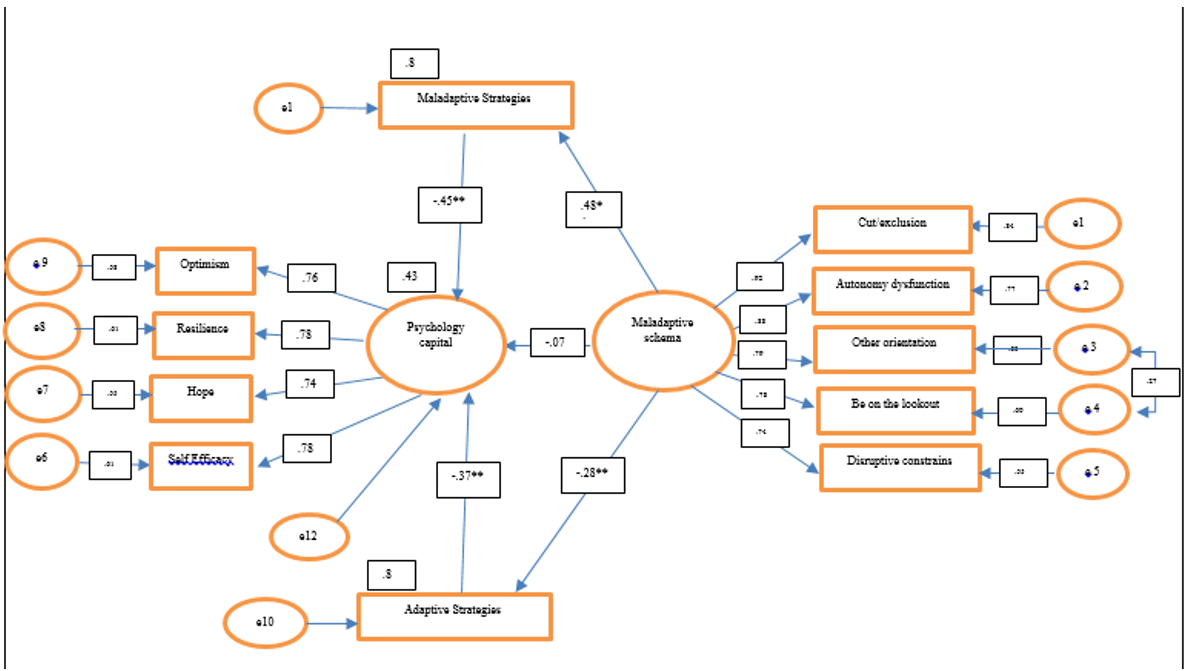

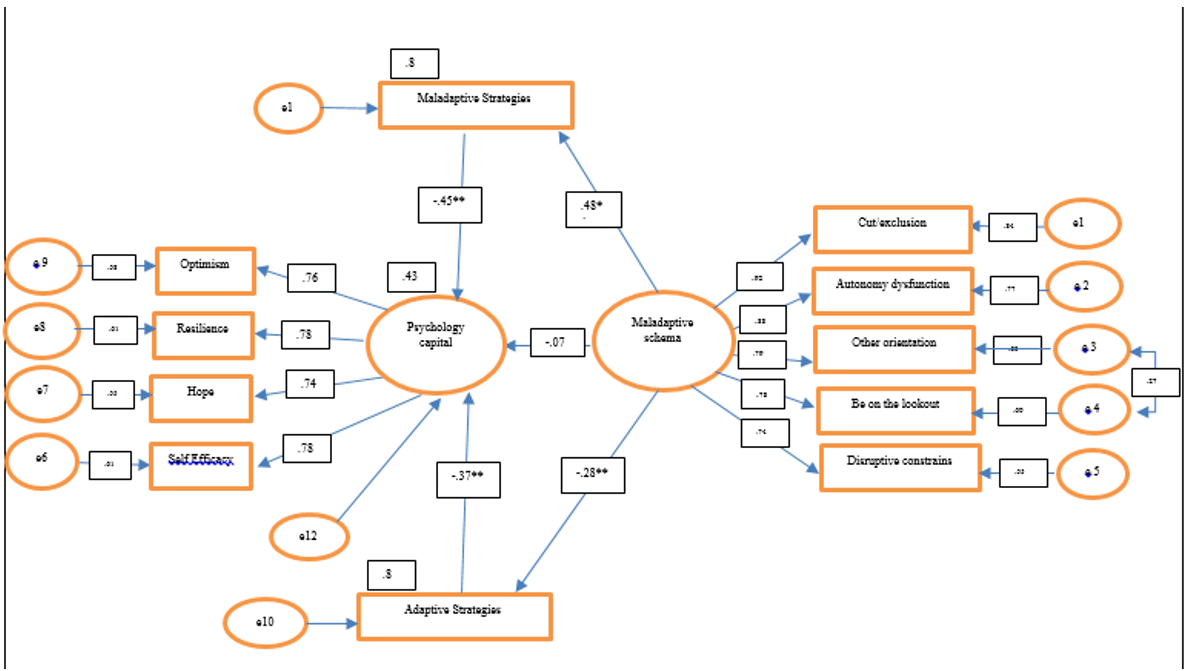

A) Measurement Model: In the present study, early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital were treated as latent variables, constituting the measurement model. It was assumed that early maladaptive schemas would be measured by indicators of cut-off/rejection, impaired autonomy and functioning, otherness, alertness, and impaired limitations, while psychological capital would be measured by indicators of self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism (Figure 1).

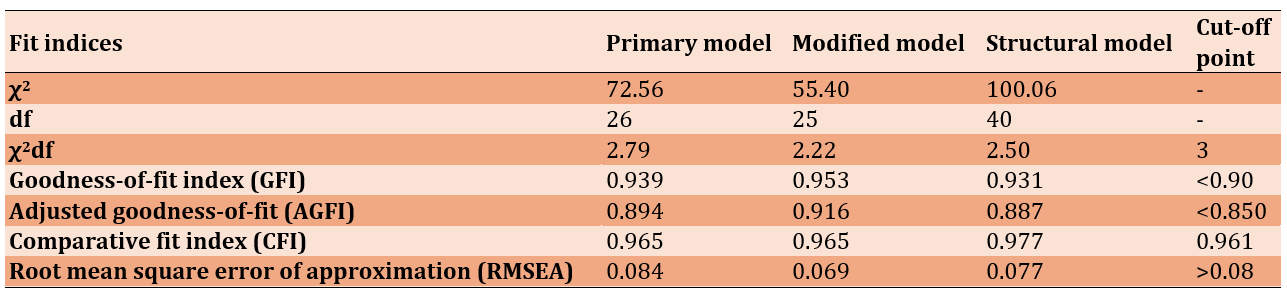

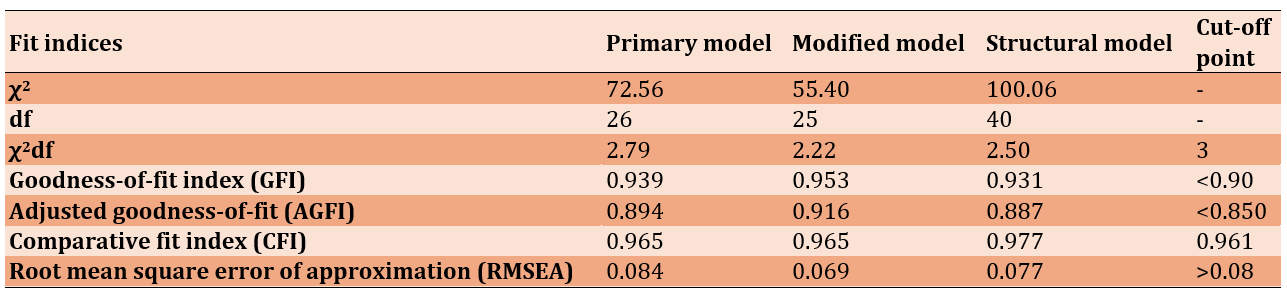

The fit of the measurement model to the collected data was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis conducted with AMOS version 24 and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation (Table 2).

Table 2. Fit indices of the measurement and structural models

With the exception of the RMSEA, the other fit indices from the confirmatory factor analysis supported an acceptable fit of the measurement model with the data. The measurement model was modified by introducing a covariance between errors related to self-regulation and impaired functioning. After the model modification, the fit indices were obtained, indicating that the measurement model had an acceptable fit with the data.

In the measurement model, the largest factor loading was associated with self-regulation and impaired functioning (β=0.895), while the smallest factor loading was associated with optimism (β=0.743). Factor loadings of 0.71 and above are considered excellent, loadings between 0.63 and 0.70 are considered very good, loadings between 0.55 and 0.62 are considered good, loadings between 0.45 and 0.55 are considered relatively good, loadings between 0.32 and 0.44 are considered low, and loadings below 0.32 are considered weak. Since all factor loadings were higher than 0.32, they can be considered adequate for measuring the latent parameters.

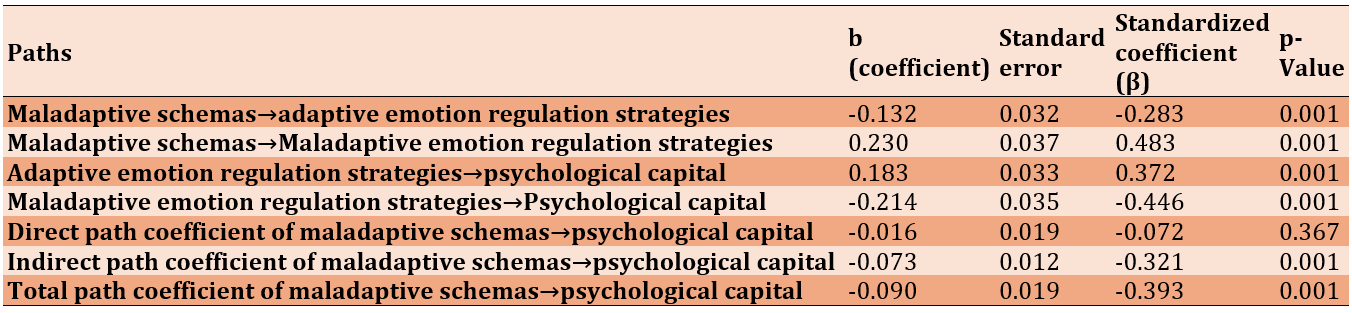

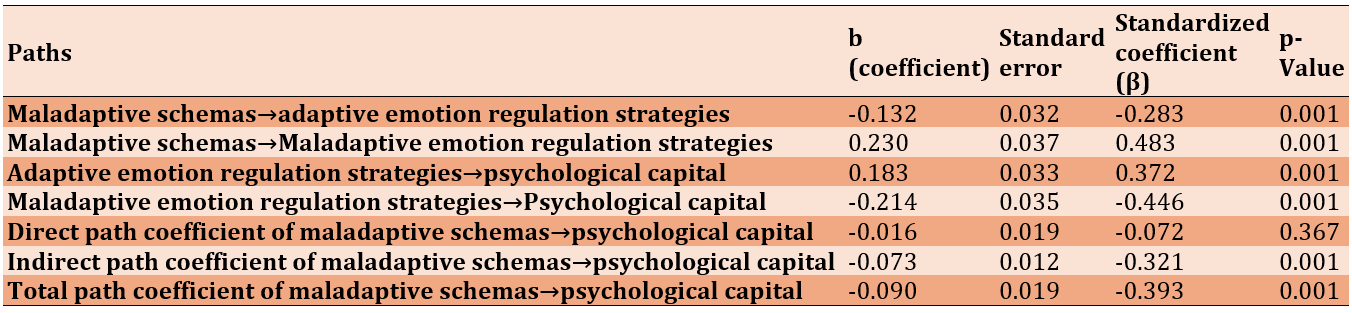

B) Structural model: In the structural model, it was assumed that early maladaptive schemas, mediated by cognitive emotion regulation, predict psychological capital in children of veterans. Structural equation modeling was used to test the model. All the fit indices obtained from the structural equation modeling supported an acceptable fit of the structural model with the data (Table 3).

Table 3. Path coefficients in the structural model

The total path coefficient between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.393) is negative and significant. The path coefficient for adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with psychological capital (p=0.001, β=0.372) is positive, while the path coefficient between maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.446) is negative and significant. The indirect path coefficient between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.321) is also negative and significant. Furthermore, the indirect path coefficients between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital through maladaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=-0.216) and through adaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=-0.104) of cognitive emotion regulation are negative and significant. Both adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies negatively and significantly mediate the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans.

Figure 1. Standard parameters in the structural model.

The sum of squared multiple correlations for the psychological capital variable was 0.43. Thus, early maladaptive schemas and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explained a total of 43% of the variance in psychological capital in children of veterans (Figure 1).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans. Early maladaptive schemas, along with their moderating role in cognitive emotion regulation, could predict psychological capital in children of veterans. Early maladaptive schemas negatively predicted psychological capital, while adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively predicted it, and maladaptive strategies negatively predicted it. These findings are consistent with those of other studies [7-9, 12]. In general, early maladaptive schemas affected psychological capital, and early maladaptive schemas, in conjunction with cognitive emotion regulation, also affected psychological capital. In other words, as cognitive emotion regulation (both adaptive and maladaptive strategies) increased, psychological capital in individuals decreased.

Early maladaptive schemas, influenced by traumatic factors in childhood (especially relationships with parents), can affect an individual’s attitude and relationships with themselves, others, and their surrounding environment in adulthood. This issue has a semantic relationship with psychological capital, which is associated with components such as hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience. According to Luthans, psychological capital enables individuals to believe in their abilities, succeed in performing certain tasks, create successful attributions about themselves, persevere in pursuing goals and the necessary follow-ups to achieve success, tolerate problems, return to a normal level of performance, and improve their outcomes in achieving success [7].

Veterans have experienced accidents and injuries caused by war during the Sacred Defense. This may affect their relationships with their children and can lead to the formation of dysfunctional schemas in them. As a result, their early maladaptive schemas may be activated in adulthood when they are exposed to various situations, incidents, and events, impacting their performance. In the children of veterans, the activation of early maladaptive schemas has been associated with a decrease in psychological capital.

The causal model also showed that the structural relationships of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively and significantly predicted psychological capital in the children of veterans, while maladaptive strategies negatively and significantly predicted it. Additionally, both adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies negatively and significantly mediated the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies [19, 20, 23, 24]. Therefore, when children of veterans use adaptive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital increases, whereas when they use maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital decreases. Furthermore, cognitive emotion regulation, considered a mediating variable, helps individuals regulate negative arousal and emotions.

Emotions and their manifestations are among the issues that people encounter every day. Emotion regulation is based on awareness and understanding of emotions, acceptance of emotions, the ability to control impulsive behaviors, and acting following desired goals to achieve personal objectives and meet situational demands.

According to Young’s theory, a schema is a long-term, stable pattern that develops in childhood and continues into adulthood, through which we perceive the world around us. Schemas are beliefs about ourselves and others that people usually accept without question. They are self-perpetuating, highly resistant to change, and typically do not change except in the context of therapy. Even a major success in life does not seem sufficient to alter them. Schemas fight for their survival and are often successful in this regard [25]. Nejat Akfirat et al. assessed the relationship between levels of psychological well-being and self-esteem, perceived general self-efficacy, and found that self-esteem, general self-efficacy, level of hope, and positive reappraisal (of cognitive emotion regulation strategies) significantly predict psychological well-being [32].

In summary, our results provided deep insight into the relationship between early maladaptive schemas, cognitive emotion regulation, and psychological capital in children of veterans. This indicates that the mechanism by which early maladaptive schemas affect the components of psychological capital—based on self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, each of which is a positive construct—has positive psychological value and function, highlighting the importance of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in children. Therefore, the increase in early maladaptive schemas led to an increase in the use of maladaptive strategies and a decrease in the use of adaptive strategies. In this study, the high level of early maladaptive schemas, along with the role of cognitive emotion regulation, resulted in a decrease in the level of psychological capital.

This study, like other studies, has limitations. First, the questionnaires were provided to the participants through cyberspace, making it impossible to control for intervening variables. Second, this study was based on a sample of children of veterans living in Tehran, which limits the generalizability of the results.

To overcome these limitations, it is recommended to use multiple assessment methods, conduct research at other levels and with larger samples, and explore the field of schema therapy and cognitive emotion regulation to examine their effects on psychological capital. Additionally, involving counselors, clinical specialists, and others who work in the psychological treatment of veterans and their children is advised.

Conclusion

Cognitive emotion regulation mediated and explained the causal relationships between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank and appreciate all those who cooperated and assisted in this research, as well as the respected officials of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation, the precious veterans who are the pride of Iran, and the children of veterans who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Ethical Permissions: This research was conducted with the ethics code number ir.essar.rec.1401.008, with the permission of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation. All participants were assured that their information would remain completely confidential during the testing phase.

Authors' Contribution: Elahian MS (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/ (40%); Rezakhani S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Dokanehifard F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research is extracted from the doctoral dissertation of the first author.

Children of veterans are exposed to psychological issues and experience symptoms related to their fathers during their time with their parents [1]. Although it is assumed that trauma affects the victim’s relationships with all family members, studies have shown that the relationship between a traumatized veteran and his or her child is often characterized by conflict, control, excessive closeness, and overprotection. This, in turn, may lead to various psychopathological symptoms among the children of veterans, a phenomenon known as “secondary trauma” [2]. Secondary traumatic stress refers to the transmission of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like symptoms from an individual who was directly exposed to a traumatic event to another individual with whom they have close and ongoing contact [3, 4]. Therefore, it is important to address the various emotional and psychological issues faced by these individuals [5].

Today, psychology has moved away from focusing solely on pathology, and the positive psychology approach has also become a central focus for researchers in this field. One of these positive components is the existence of psychological capital, which is considered one of the most important characteristics for individuals’ adaptation to difficult conditions and for enhancing their quality of life [6]. According to Luthans and Youssef, psychological capital is composed of four constructs: hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Each of these can be considered a positive psychological capacity that has the potential to grow and is significantly related to performance outcomes [7]. Having psychological capital enables individuals to cope better with stressful situations, feel less stressed, exhibit high resilience in the face of problems, achieve a clear view of themselves, and be less affected by daily events [8].

Psychological capital predicts problem-solving ability in students [9], health-promoting behaviors in the elderly [10], and life satisfaction as well as marital satisfaction in spouses of veterans [11]. In this regard, cognitive reappraisal and positive psychological capital moderate the relationship between perceived stress and depression, significantly inhibiting depression in individuals with both high and low stress levels [12].

Another crucial and sensitive intrapersonal factor affecting interpersonal relationships in children of veterans is cognitive emotion regulation. Cognitive emotion regulation is very important in life, and one of the most common methods involves the use of cognitive emotion strategies [13, 14]. Cognitive emotion regulation refers to how an individual can organize their attention and achieve strategic and persistent actions to solve problems [15]. In other words, emotion regulation encompasses conscious or unconscious cognitive, emotional, and behavioral strategies that are used to maintain, increase, or decrease emotions [16].

Garnefski and Kraaij believe that cognitive emotion regulation strategies are cognitive processes that individuals use to cope with stressful situations and manage arousing information. These strategies focus on the cognitive dimension of coping; therefore, thoughts and cognitions play a significant role in the ability to manage, regulate, and control feelings and emotions after experiencing a stressful situation [17]. In this context, effective emotion regulation can strengthen self-esteem, which, in turn, enables individuals to respond adaptively to stress [18]. Guo et al. demonstrated the special role of the dimensions of emotion regulation in relation to psychological capital and cognitive resilience [19]. Emotion regulation has a positive relationship with psychological resilience and may facilitate both emotion-focused and problem-focused coping strategies, thereby promoting psychological resilience [20].

On the other hand, children of veterans have different mental frameworks compared to others in society due to secondary trauma. In this context, a concept called primary maladaptive schemas is proposed. Primary maladaptive schemas can be considered deep and pervasive themes that encompass memories, cognitions, and bodily sensations. These schemas, which are relevant to one’s relationship with oneself and others, can cause dissatisfaction in relationships by creating primary emotional and cognitive barriers [21]. Young has presented a schema model focused on cognitive behavioral problems. According to him, primary maladaptive schemas are deep and pervasive internal patterns formed in childhood or adolescence that persist throughout life, are related to the individual’s relationship with themselves and others, and are highly dysfunctional [22].

Amini and Khoshravesh believe that schemas determine how individuals approach and view themselves, the world, and the future. If schemas are positive, the individual’s perspective will be hopeful and successful; conversely, if schemas are negative, the individual may view themselves as incompetent and worthless, perceive obstacles in facing challenges as impenetrable, and experience failure in every attempt. Such an individual is likely to develop a negative outlook on the world around them and on the future [23]. In this regard, Gorji and Salehi demonstrated that early maladaptive schemas and cognitive emotion regulation strategies can predict resilience and quality of life [24].

The specific geographical and political conditions of our country in the region, the situation in the Middle East, the outbreak of successive wars in this area, and the voluntary presence of individuals with religious convictions calling for the defense of the Shrine of the Innocents (PBUH) contribute to the perception that our country is perpetually involved in conflict. A significant portion of our population is imbued with religious attitudes, which further influences this perception. Most research has focused on the effects of the imposed war from the time it began to the present, and the direct psychological impact of experiencing severe psychological trauma, such as that caused by war, has been thoroughly and comprehensively studied over the past half-century. However, the secondary impact of living with someone who suffers from PTSD has been much less examined. While soldiers and veterans are directly affected by war, their children and families are the indirect victims of these events. Physical trauma can create a ripple effect that impacts not only the victims themselves but also those close to them, particularly their children. Children of veterans are often raised by fathers who carry injuries and traumas from the war, and the veterans’ attitudes toward life are reflected in their communication patterns with their children. Given the significance of this issue, the present study aimed to investigate the causal relationships between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans, with cognitive emotion regulation serving as a mediating factor.

Instrument and methods

This descriptive fundamental research employed structural equation modeling analysis. The research population included children (girls and boys) of veterans residing in Tehran, aged between 18 and 40 years, covered by the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs from April to September 2022, totaling 86,642 individuals. The sample size was estimated to be 247 individuals. The questionnaires were designed using Press Line, and after receiving the questionnaire link, they were sent to the research sample through the Short Message Service Centre in coordination with a phone call from the Call Center of the Veterans Engineering and Medical Sciences Research Institute. Considering the possibility of dropouts, the number of participants was increased to 260. The questionnaires were answered online. After removing seven incomplete questionnaires, 253 questionnaires were analyzed. Since the list of all individuals in the research population was not available to the researcher, the available sampling method was used.

Data collection

Three questionnaires were utilized for data collection.

Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form: This questionnaire was designed by Young et al. to measure 15 schemas across five domains: rejection and abandonment, impaired autonomy and functioning, impaired limitations, other-orientation, and alertness. It consists of 75 questions. Each item of this questionnaire is scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from completely false to completely true (completely false=1, almost false=2, more true than false=3, slightly true=4, almost true=5, completely true=6). Scores above 25 in each subscale indicate a maladaptive schema [25]. Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales in non-clinical populations ranged from 0.50 to 0.82. The validity of the questionnaire has also been reported as satisfactory [26]. The standardization of this questionnaire in a student sample in Iran was calculated using the internal consistency method through Cronbach’s alpha, yielding values of 0.94 for cut-off and exclusion, 0.91 for self-regulation and impaired functioning, 0.87 for other-orientation, 0.88 for alertness, and 0.85 for impaired limitations. The values for women were 0.97, while for men, it was 0.98 [27].

Luthans Psychological Capital Questionnaire: This questionnaire was designed by Luthans et al. in 2007 to measure psychological capital. It consists of 24 questions and four subscales: hopefulness, resilience, optimism, and self-efficacy, with each subscale containing six items. The test taker answers each item on a 6-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). To obtain the psychological capital score, the score for each subscale is calculated separately, and their sum is considered the total psychological capital score. High or low scores indicate the level of psychological capital of the individual [7]. In the study by Youssef & Luthans, Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale (hopefulness, resilience, self-efficacy, optimism) was obtained at 0.88, 0.89, 0.89, and 0.89, respectively [28]. The reliability of the questionnaire has also been reported in Iran by Bahadori Khosroshahi et al. [29], based on a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ): This questionnaire was developed by Garnefski and Kraaij to measure cognitive regulation strategies. It is a self-report instrument consisting of 36 questions that are scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never (one) to always (five). The minimum possible score is 36, and the maximum is 180. A higher score indicates a greater use of that cognitive strategy by the individual [7]. Cognitive strategies for emotion regulation are divided into two general categories: adaptive strategies, which include positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, acceptance, and refocusing on planning, and maladaptive strategies, which include self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing. The alpha coefficient for the subscales of this questionnaire was reported by Garnefski et al. to range from 0.71 to 0.81 [30]. In Iran, the results of the retest of the subscales of this questionnaire, with an interval of one week, ranged from 0.75 to 0.88, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for adaptive strategies was reported to be 0.90, while for maladaptive strategies, it was 0.87 [31].

Data Analysis:

To analyze the data at the descriptive level, the mean and standard deviation were used. To examine the main hypotheses and their subscales, the Pearson correlation coefficient, regression analysis, and path analysis were employed using the AMOS software 24.

Findings

A total of 253 children of veterans (129 women and 124 men), with a mean age of 30.56±7.49 years, participated in this study. Among the participants, 112 (44.3%) were single, and 141 (55.7%) were married. Regarding educational levels, 44 cases (17.4%) had a diploma or less, 13 (5.1%) had a post-diploma, 107 (42.3%) had a bachelor’s degree, 73 (28.9%) had a master’s degree, and 16 (6.3%) held a PhD degree. The level of injury percentage was less than 25% for 148 participants (58.5%), 26 to 40% for 62 cases (24.5%), and more than 40% for the remaining participants. It should be noted that in 193 (participants 76.3%), their parents were injured before their birth (Table 1).

Table 1. Mean values and correlation coefficients between research parameters

To evaluate the assumption of normal distribution of univariate data, the kurtosis and skewness were examined. To assess the assumption of collinearity, the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance coefficient were analyzed. To determine whether the assumption of normal distribution of multivariate data is valid, the “Mahalanobis distance” was utilized. The skewness and kurtosis values were obtained as 1.12 and 0.89, respectively were within the range of ±2, supporting the normal distribution of multivariate data. Finally, to evaluate the homogeneity of variances, the scatter plot displaying the standardized error variances was used, and this assumption was also valid.

Model Analysis

A) Measurement Model: In the present study, early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital were treated as latent variables, constituting the measurement model. It was assumed that early maladaptive schemas would be measured by indicators of cut-off/rejection, impaired autonomy and functioning, otherness, alertness, and impaired limitations, while psychological capital would be measured by indicators of self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism (Figure 1).

The fit of the measurement model to the collected data was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis conducted with AMOS version 24 and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation (Table 2).

Table 2. Fit indices of the measurement and structural models

With the exception of the RMSEA, the other fit indices from the confirmatory factor analysis supported an acceptable fit of the measurement model with the data. The measurement model was modified by introducing a covariance between errors related to self-regulation and impaired functioning. After the model modification, the fit indices were obtained, indicating that the measurement model had an acceptable fit with the data.

In the measurement model, the largest factor loading was associated with self-regulation and impaired functioning (β=0.895), while the smallest factor loading was associated with optimism (β=0.743). Factor loadings of 0.71 and above are considered excellent, loadings between 0.63 and 0.70 are considered very good, loadings between 0.55 and 0.62 are considered good, loadings between 0.45 and 0.55 are considered relatively good, loadings between 0.32 and 0.44 are considered low, and loadings below 0.32 are considered weak. Since all factor loadings were higher than 0.32, they can be considered adequate for measuring the latent parameters.

B) Structural model: In the structural model, it was assumed that early maladaptive schemas, mediated by cognitive emotion regulation, predict psychological capital in children of veterans. Structural equation modeling was used to test the model. All the fit indices obtained from the structural equation modeling supported an acceptable fit of the structural model with the data (Table 3).

Table 3. Path coefficients in the structural model

The total path coefficient between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.393) is negative and significant. The path coefficient for adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with psychological capital (p=0.001, β=0.372) is positive, while the path coefficient between maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.446) is negative and significant. The indirect path coefficient between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital (p=0.001, β=-0.321) is also negative and significant. Furthermore, the indirect path coefficients between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital through maladaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=-0.216) and through adaptive strategies (p=0.001, β=-0.104) of cognitive emotion regulation are negative and significant. Both adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies negatively and significantly mediate the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans.

Figure 1. Standard parameters in the structural model.

The sum of squared multiple correlations for the psychological capital variable was 0.43. Thus, early maladaptive schemas and cognitive emotion regulation strategies explained a total of 43% of the variance in psychological capital in children of veterans (Figure 1).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans. Early maladaptive schemas, along with their moderating role in cognitive emotion regulation, could predict psychological capital in children of veterans. Early maladaptive schemas negatively predicted psychological capital, while adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively predicted it, and maladaptive strategies negatively predicted it. These findings are consistent with those of other studies [7-9, 12]. In general, early maladaptive schemas affected psychological capital, and early maladaptive schemas, in conjunction with cognitive emotion regulation, also affected psychological capital. In other words, as cognitive emotion regulation (both adaptive and maladaptive strategies) increased, psychological capital in individuals decreased.

Early maladaptive schemas, influenced by traumatic factors in childhood (especially relationships with parents), can affect an individual’s attitude and relationships with themselves, others, and their surrounding environment in adulthood. This issue has a semantic relationship with psychological capital, which is associated with components such as hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience. According to Luthans, psychological capital enables individuals to believe in their abilities, succeed in performing certain tasks, create successful attributions about themselves, persevere in pursuing goals and the necessary follow-ups to achieve success, tolerate problems, return to a normal level of performance, and improve their outcomes in achieving success [7].

Veterans have experienced accidents and injuries caused by war during the Sacred Defense. This may affect their relationships with their children and can lead to the formation of dysfunctional schemas in them. As a result, their early maladaptive schemas may be activated in adulthood when they are exposed to various situations, incidents, and events, impacting their performance. In the children of veterans, the activation of early maladaptive schemas has been associated with a decrease in psychological capital.

The causal model also showed that the structural relationships of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies positively and significantly predicted psychological capital in the children of veterans, while maladaptive strategies negatively and significantly predicted it. Additionally, both adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies negatively and significantly mediated the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies [19, 20, 23, 24]. Therefore, when children of veterans use adaptive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital increases, whereas when they use maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, their psychological capital decreases. Furthermore, cognitive emotion regulation, considered a mediating variable, helps individuals regulate negative arousal and emotions.

Emotions and their manifestations are among the issues that people encounter every day. Emotion regulation is based on awareness and understanding of emotions, acceptance of emotions, the ability to control impulsive behaviors, and acting following desired goals to achieve personal objectives and meet situational demands.

According to Young’s theory, a schema is a long-term, stable pattern that develops in childhood and continues into adulthood, through which we perceive the world around us. Schemas are beliefs about ourselves and others that people usually accept without question. They are self-perpetuating, highly resistant to change, and typically do not change except in the context of therapy. Even a major success in life does not seem sufficient to alter them. Schemas fight for their survival and are often successful in this regard [25]. Nejat Akfirat et al. assessed the relationship between levels of psychological well-being and self-esteem, perceived general self-efficacy, and found that self-esteem, general self-efficacy, level of hope, and positive reappraisal (of cognitive emotion regulation strategies) significantly predict psychological well-being [32].

In summary, our results provided deep insight into the relationship between early maladaptive schemas, cognitive emotion regulation, and psychological capital in children of veterans. This indicates that the mechanism by which early maladaptive schemas affect the components of psychological capital—based on self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience, each of which is a positive construct—has positive psychological value and function, highlighting the importance of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in children. Therefore, the increase in early maladaptive schemas led to an increase in the use of maladaptive strategies and a decrease in the use of adaptive strategies. In this study, the high level of early maladaptive schemas, along with the role of cognitive emotion regulation, resulted in a decrease in the level of psychological capital.

This study, like other studies, has limitations. First, the questionnaires were provided to the participants through cyberspace, making it impossible to control for intervening variables. Second, this study was based on a sample of children of veterans living in Tehran, which limits the generalizability of the results.

To overcome these limitations, it is recommended to use multiple assessment methods, conduct research at other levels and with larger samples, and explore the field of schema therapy and cognitive emotion regulation to examine their effects on psychological capital. Additionally, involving counselors, clinical specialists, and others who work in the psychological treatment of veterans and their children is advised.

Conclusion

Cognitive emotion regulation mediated and explained the causal relationships between early maladaptive schemas and psychological capital in children of veterans.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank and appreciate all those who cooperated and assisted in this research, as well as the respected officials of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation, the precious veterans who are the pride of Iran, and the children of veterans who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Ethical Permissions: This research was conducted with the ethics code number ir.essar.rec.1401.008, with the permission of the Martyr and Veterans Affairs Foundation. All participants were assured that their information would remain completely confidential during the testing phase.

Authors' Contribution: Elahian MS (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/ (40%); Rezakhani S (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%); Dokanehifard F (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (20%)

Funding/Support: This research is extracted from the doctoral dissertation of the first author.

Keywords:

References

1. Fakhri Z, Danesh E, Shahidi Sh, Seliminia AR. Quality of value system and self-efficacy beliefs in children with veteran and non-veteran fathers. J Appl Psychol. 2013;6(4):25-42. [Persian] [Link]

2. Solomon Z, Debby-Aharon Sh, Zerach G, Horesh D. Marital adjustment parental functioning and emotional sharing in war veterans. J Fam Issues. 2011;32(1):127-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0192513X10379203]

3. Rauvola RS, Vega DM, Lavigne KN. Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization: A qualitative review and research agenda. Occup Health Sci. 2019;3(3):297-336. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s41542-019-00045-1]

4. Polak S, Bailey R, Bailey E. Secondary traumatic stress in the courtroom suggestions for preventing vicarious trauma resulting from child sexual abuse imagery. Juv Fam Court J. 2019;70(2):69-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jfcj.12137]

5. Rezapour Mirsaleh Y, Zakeri F, Amini R, Eslamifard M. A study of the relationship between psychological acceptance and self-compassion and attitude to seeking psychological help in the children of disabled veterans. Sci J Mil Psychol. 2021;12(45):7-19. [Persian] [Link]

6. Etikariena A. The effect of psychological capital as a mediator variable on the relationship between work happiness and innovative work behavior. In: Diversity in unity: Perspectives from psychology and behavioral sciences. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 379-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1201/9781315225302-46]

7. Luthans F, Youssef CM. Emerging positive organizational behavior. J Manag. 2007;33(3):321-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0149206307300814]

8. Azimi D, Gadimi S, Khazan K, Dargahi S. The role of psychological capitals and academic motivation in academic vitality and decisional procrastination in nursing students. J Med Educ Dev. 2017;12(3):147-57. [Persian] [Link]

9. Askari F, Tajrobehkar M, Towhidi A. The role of psychological capital on the ability to solve social problems through mediation intellectual preferences. Posit Psychol Res. 2021;7(2):73-88. [Persian] [Link]

10. Bakhshi N, Pashang S, Jafari N, Ghorban-Shiroudi S. Developing a model of psychological well-being in elderly based on life expectancy through mediation of death anxiety. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2020;8(3):283-93. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijhehp.8.3.283]

11. Golparvar M, Ghasemi M, Mosahebi M. Role patterns of psychological capital factors on life and marital satisfaction among war survivor's wives in Shahrekord City. Womens Stud. 2014;12(1):119-40. [Persian] [Link]

12. Liu Y, Yu H, Shi Y, Ma C. The effect of perceived stress on depression in college students: The role of emotion regulation and positive psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1110798. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1110798]

13. Garavand P, Manshei Gh. The effectiveness of teaching forgiveness based on Enright model and enriching the relationships on mental wellbeing and life quality of dissatisfied women from their marital life in the city of Khoram Abad. Middle Eastern J Disabil Stud. 2015;5:190-9. [Persian] [Link]

14. Luthans F. The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J Organ Behav. 2002;23(6):695-706. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/job.165]

15. Javadpour M, Rezaee A, Javidi H, Khayyer M. Effectiveness of cognitive emotional regulation training on the impulsivity and peer relationship in high school students: A pilot study. Community Health. 2022;9(2). [Persian] [Link]

16. Strauss AY, Kivity Y, Huppert JD. Emotion regulation strategies in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Behav Ther. 2019;50(3):659-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2018.10.005]

17. Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire-development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personal Individ Differ. 2006;41(6):1045-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010]

18. Mouatsou C, Koutra K. Emotion regulation in relation with resilience in emerging adults: The mediating role of self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(2):734-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12144-021-01427-x]

19. Guo Z, Cui Y, Yang T, Liu X, Lu H, Zhang Y, et al. Network analysis of affect, emotion regulation, psychological capital, and resilience among Chinese males during the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1144420. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1144420]

20. Polizzi CP, Lynn SJ. Regulating emotionality to manage adversity: A systematic review of the relation between emotion regulation and psychological resilience. Cogn Ther Res. 2021;45(2):577-97. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10608-020-10186-1]

21. Basharat MA, Khalili Khadzerabadi M, Rezazade SMR. The mediating role of difficulty of emotion regulation in the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and marital problems. Iran J Fam Psychol. 2017;3(2):27-44. [Persian] [Link]

22. Young JE. Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach. Sarasota: Professional Resource Exchange, Inc; 1990. [Link]

23. Amini Z, Khoshravesh V. The relationship between early maladaptive schemas and burnout with the mediating role of psychological capital. Manag Educ Perspect. 2020;2(3):133-63. [Persian] [Link]

24. Gorji M, Salehi S. The role of early maladaptive schemas and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in predicting resilience. Q J Soc Work. 2020;8(4):52-60. [Persian] [Link]

25. Young JE, Brown G. Young schema questionnaire-short form; Version 3. New York: Schema Therapy Institute; 2005. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t67023-000]

26. Oei TPS, Baranoff J. Young schema questionnaire: Review of psychometric and measurement issues. Aust J Psychol. 2007;59(2):78-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00049530601148397]

27. Ahi Q, Mohammadifar MA, Basharat MA. Reliability and validity of young's schema questionnaire-short form. J Psychol Educ. 2007;37(3):5-20. [Persian] [Link]

28. Youssef C, Luthans F. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. J Manag. 2007;33(5):774-800. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0149206307305562]

29. Bahadori Khosroshahi J, Hashemi Nosratabadi T, Bayrami M. The relationship between psychological capital and personality traits with job satisfaction in public library librarians in Tabriz. Pajoohande. 2013;17(6):312-9. [Persian] [Link]

30. Garnefski N, Van Den Kommer T, Kraaij V, Teerds J, Legerstee J, Onstein E. The relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems: Comparison between a clinical and a non-clinical sample. Eur J Personal. 2002;16(5):403-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/per.458]

31. Basharat MA, Bezazian S. Psychometri properties of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in a sample of Iranian population. Adv Nurs Midwifery. 2015;24(84):61-70. [Persian] [Link]

32. Nejat Akfirat O. Investigation of relationship between psychological well-being, self esteem, perceived general self-efficacy, level of hope and cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Eur J Educ Stud. 2020;7(9). [Link] [DOI:10.46827/ejes.v7i9.3267]