Volume 16, Issue 1 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(1): 49-60 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/12/1 | Accepted: 2024/01/8 | Published: 2024/01/28

Received: 2023/12/1 | Accepted: 2024/01/8 | Published: 2024/01/28

How to cite this article

Maryanto M, Rohmansyah N. Human Rights-Based Interpretation of the Right to Health for Indonesian War Veterans. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (1) :49-60

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1422-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1422-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

M. Maryanto *1, N.Z. Rohmansyah2

1- Department of Civics Education, Faculty of Social Sciences and Sports Education, PGRI University Semarang, Semarang, Indonesia

2- Department of Physical Education, Faculty of Social Sciences and Sports Education, PGRI University Semarang, Semarang, Indonesia

2- Department of Physical Education, Faculty of Social Sciences and Sports Education, PGRI University Semarang, Semarang, Indonesia

Full-Text (HTML) (1147 Views)

Introduction

Human rights also include the health of every person, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, religion, or nationality, and the right to accessible and acceptable medical services, medicines, and medical equipment. The right to health follows the principle of “progressive realization” [1-3], where the state is not allowed to take regressive steps and is obliged to realize the right to health [4-6].

The progressive realization also means that countries must regularly monitor how the right to health is realized and assess whether they have made sufficient progress given the available resources [7-9]. Therefore, monitoring health rights requires appropriate indicators based on human rights principles.

It is true, as can be seen by observing and paying attention to the aforementioned provisions, that every disruption, intervention, unfairness, and apathy, in whatever form, leads to unhealthy human bodies and minds, as well as unhealthy natural and social environments, laws and regulations, and unhealthiness. The social management justice they are provided violates both their human and legal rights [10-14].

The right to health does not imply that everyone must be healthy or that the government must provide ostentatious medical facilities beyond its means. However, increasing pressures are on the government and public authorities to develop policies and work plans that would result in the availability and affordability of healthcare facilities for everyone in the shortest time [15-17].

Although the right to health as a right of every person is stated in the International Covenant, it does not include health services. However, the history of the drafting and grammatical interpretation of this law, which stipulates that the measures to be taken by states parties to the present Covenant to realize this rightfully, must include the following: measures to reduce stillbirth and child death while promoting the healthy development of children, improving occupational and environmental health aspects, including all infectious diseases with prevention, management, and control [18-20].

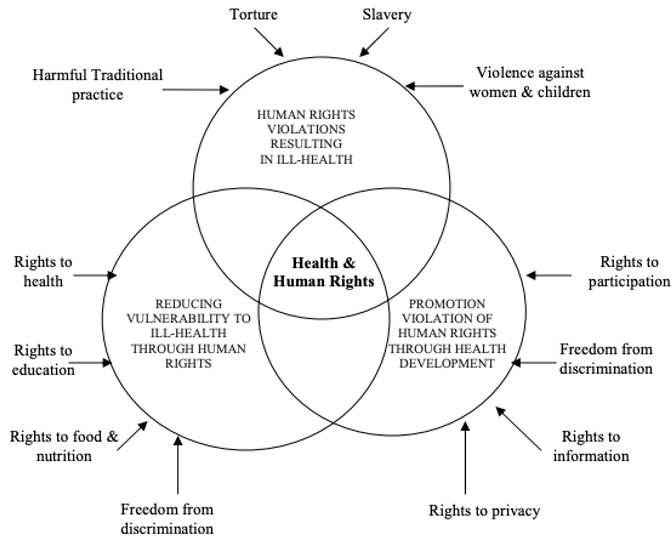

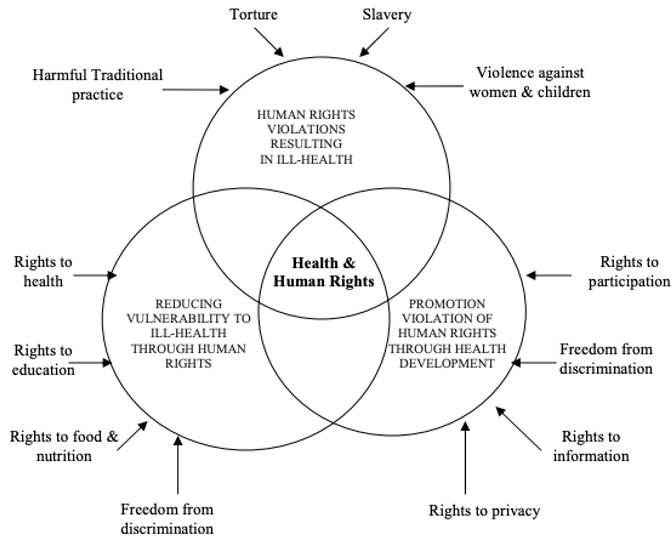

Human rights and health have a mutual influence (Figure 1). Human rights violations are also violations of the right to health. The government fails if it does not fulfill its obligations to human rights and health, as seen in the bottom right circle. Meanwhile, the upper class is closely related to the right to health, which is violated by violent practices that also violate civil and political rights. The bottom left circle depicts the relationship between human rights and health due to vulnerable social conditions [21, 22].

Figure 1. Mutual influence of human rights and health

In the meantime, several aspects of the relationship between the State and Individuals cannot be addressed alone. In particular, the State cannot ensure good health or offer protection from all potential disease causes in humans. In the meantime, several aspects of the relationship between the State and Individuals cannot be addressed alone. The State, in particular, cannot guarantee good health or protection against all potential causes of human disease. Individual risk factors for disease, as well as the adoption of risky or unhealthy lifestyles, all significantly impact an individual's health. As a result, it is critical to understand that the right to health includes the right to receive various facilities, services, and conditions necessary for attaining reasonable and sufficient health standards [23-27].

Human rights, including the right to health, have been widely recognized. However, to our knowledge, no research has been conducted on how veterans understand their right to health. We conducted a comprehensive survey to determine how well veterans understand and apply the principles underlying the right to health. Since introducing the normative principles, we have documented efforts to assess the implementation of the right to health. This study aimed to identify efforts in the public health literature to evaluate the implementation of war veterans' human rights to health.

Information and Methods

This systematic review was conducted on the global literature on the right to health or human rights-based approaches to war veterans' health.

PRISMA guidelines for Grant and Booth typology of reviews as systematic reviews and “scoping reviews” [8, 28, 29]. Various databases, including Global Health, Embase, Medline, Pubmed, and Open Grey, were utilized to gather the relevant studies. The retrieval process focused on keywords like “right to health” and “human rights-based approaches to health”. Secondary data sources and library research methods were used in this study, focusing on the government, non-governmental organizations, civil society, and intergovernmental organizations involved in human rights enforcement. This methodology is utilized because there are a lot of corroborating secondary sources. Hence, the government's websites and reports can also be used to learn about its initiatives to uphold and defend human rights under the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In the meantime, the authors were able to locate comments from state commissions from outside actors, as well as journals, articles, newspapers, reports, and INGO websites.

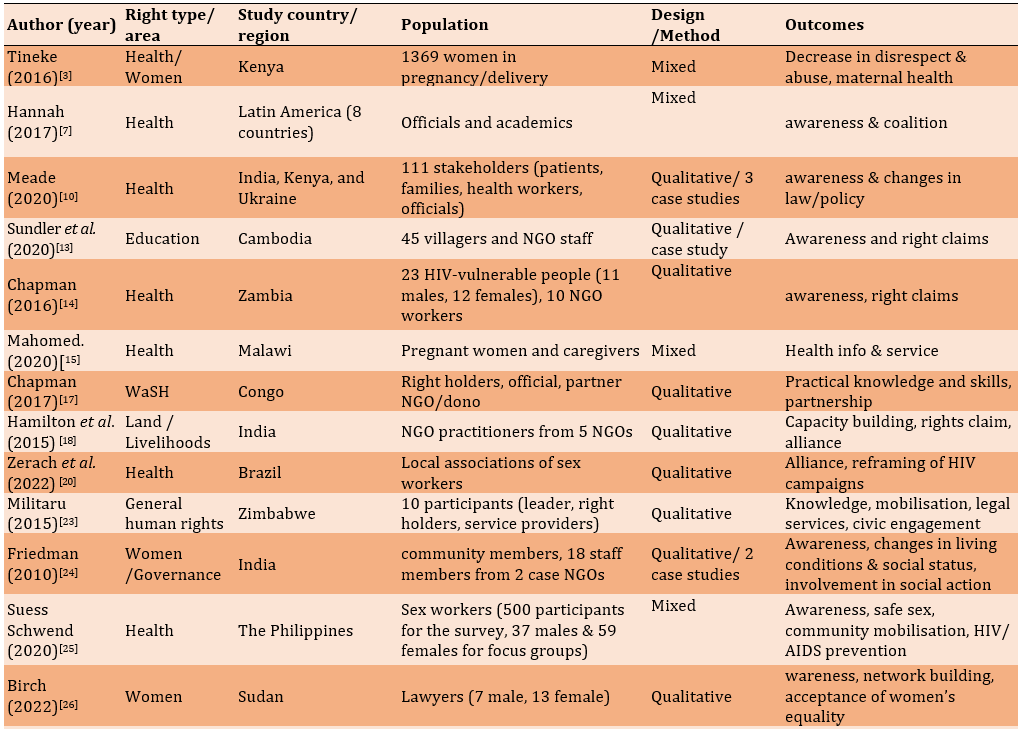

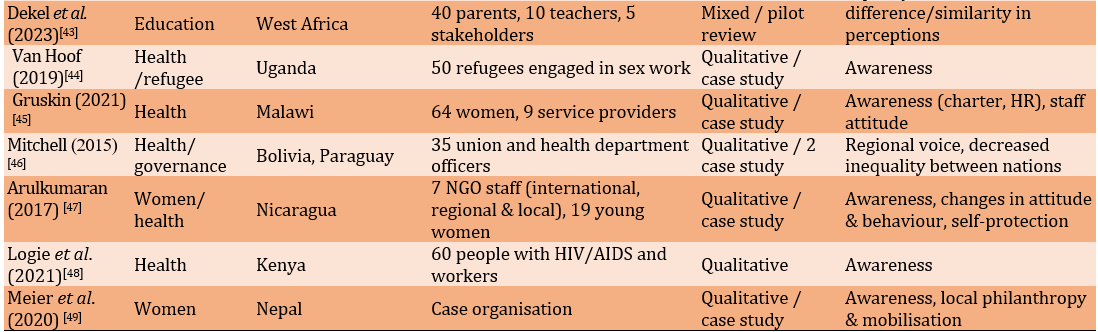

The database search produced 6250 studies by checking the full text and then filtering the titles and abstracts, resulting in 66 studies, which were then included in the analysis and obtained 29 studies, with the majority of research references being general [30-32], namely the right to health included in the health and human system; an update of scientific indicators for the right to health; and the right to health assessments that use innovative methods. These studies were mainly applied in the fields of maternal and reproductive and child health, tuberculosis, and HIV in war veterans [33-35] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PRISMA flowchart of the study

Findings

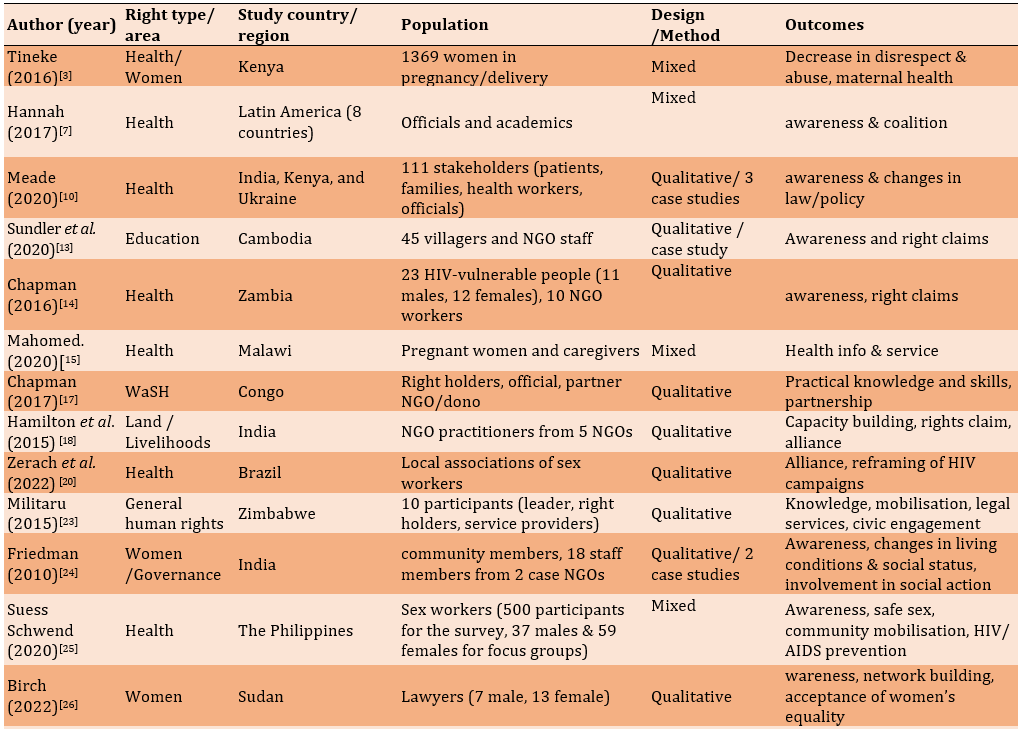

121 studies were collected from various databases that examined human rights to health practices or how to measure them. 66 studies (54.5%) which established new frameworks for assessing the human right to health implementation, applying new indicators to evaluate and assess whether policies and programs fall under the human right to health. Finally, 29 studies used health indicators in implementing the human right to health by referring to cases based on laws, policies, and programs [36-41]. A bibliographic search was used to find interdisciplinary health and human rights journal studies. These studies help differentiate how the right to health is discussed and evaluated in the public health and human rights literature (Table 1).

Table 1. Extracted data from the final documents

Discussion

This study aimed to identify efforts in the public health literature to evaluate the implementation of war veterans' human rights to health. This review included the following 78 studies. Veterans' right to health was not adequately addressed in public health research. Research often focuses on physical availability, access to medicines and healthS services, and measures of disaggregated health outcomes. Human rights policy does not address the right to health, despite some public health research indicating a link between health outcomes and human rights. In the field of public health, the sources of the right to health are well known.

Health is a subjective concept that encompasses a wide range of factors, such as socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic context. As a result, defining what is covered by the right to health is difficult. Experts, activists, and UN agencies are attempting to provide information about the essential elements of the right to health. The following components comprise core content, a set of requirements that must always be met, regardless of resource availability:

1) Health care includes immunization, appropriate treatment for common illnesses and accidents, and the distribution of basic medicines. Health care for mothers and children, including family planning; and

2) Basic health prerequisites include promoting appropriate food and nutrition, providing clean water and basic sanitation, and educating people about health issues and how to prevent and control them.

The aforementioned elements cannot be fully classified when examining the relationship between health and human rights. This means that the right to health does not necessitate adding health-related elements already covered by other human rights [13-15, 17, 22].

Meanwhile, the right to health is broadly defined by characterizing the contents of this right:

1) Reducing the mortality rate of infants and children under the age of five; sexual and reproductive health services; reproductive health access and resources; access to family planning; and emergency services in the field of obstetrics;

2) The right to a safe and healthy working environment, including clean drinking water, preventive measures against occupational diseases and accidents, and basic sanitation that prevents harmful substances such as radiation, chemicals, and environmental hazards. Industrial sanitation ensures adequate food and nutritional supplies, a clean and sanitary work environment, and adequate and safe housing. It prevents the use of alcohol, tobacco, drugs, and other harmful substances;

3) The right to prevent, control, and investigate diseases, including occupational diseases and endemic and epidemic diseases; the development of prevention initiatives and behavioral education related to health, sexual and reproductive health, including efforts to address HIV/AIDS, STDs, and improving social determinants of health, such as gender equality, education, economic growth, a safe environment, and assistance from natural disasters;

4) The right to goods, services, and facilities for health: ensuring the provision of medical services that encompass preventive, curative, promotive, and rehabilitative measures for the body and mind; supply of necessary medications; appropriate psychiatric medicine or care; increasing community participation in health initiatives such as insurance programs, health sector organizations, and, in particular, national and international political decision-making; and

5) Some specific topics and broader applications are the gender perspective, elder care, people with disabilities, children and adolescents' health, non-discrimination and equal treatment, and indigenous communities.

As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed health indicators to assess the development, implementation, and fulfillment of health-related rights. This commitment is also binding on Indonesia, which has established 50 health indicators that must be met [42].

To ensure human rights regarding the right to health, the state fulfills its obligations guided by the following principles:

1) The state must provide various health services to the entire population;

2) The state must provide health facilities, goods, and services within its jurisdiction for all people without discrimination, physical access, economic access, and information access to seek, receive, and/or disseminate information and ideas regarding health issues;

3) Medical ethics is used in all health facilities, goods, and services and is culturally appropriate; and

4) A scientific and medical viewpoint is used in all health products, facilities, and services and is culturally acceptable to protect the confidentiality of health status information. This includes, among other things, medically trained personnel, legally approved medications, and unexpired scientific and hospital equipment while improving the health of those in need.

Meanwhile, the three types of state obligations to protect the right to health are as follows:

1) The state's primary concern within this framework is "what will not be done" or "what will be avoided" in terms of policies or actions. States must exercise restraint and refrain from taking any actions that could harm public health. Examples of such actions include not enacting laws that restrict access to healthcare services, not discriminating, not concealing or distorting vital health information, refusing to accept international agreements without first weighing the potential effects on the right to health, and not distributing dangerous medications;

2) The state's primary duty is to enact laws or take other measures that ensure equitable access to health services from outside providers. Laws, standards, regulations, and guidelines should be created to safeguard employees, society, and the environment. Control and regulate traditional healing methods that are known to be harmful to health, as well as the marketing and distribution of substances that are harmful to health, such as alcohol, tobacco, and others; and

3) The government's responsibilities in this situation include providing health facilities and services, adequate food, health-related information and education, services for pre-existing conditions, and social factors that affect health, such as gender equality, equal access to employment, and children's rights. Identity, education, a lack of exploitation or violence, and sexual offenses that harm health are all important considerations.

States must take human rights steps toward fulfilling the right to health to gradually achieve the full realization of this right for war veterans, as mandated in the International Covenant [43, 44].

The right to health is an inseparable part of one of the fundamental human rights and a basic need that cannot be compromised under any circumstances. Therefore, regardless of religion, ethnicity, economic situation, social situation, and political background, the state should be able to fulfill the right to health as one of the basic rights of every individual that must be respected. The right to health is included in the family of economic, social, and cultural rights but intersects with civil and political rights. Health, as a human right, is a broad subject. Various expert opinions support the link. Human rights and health are interconnected approaches that complement the concept of human well-being. The right to health, in all its forms and at all levels, contains important and interconnected elements. Local conditions will greatly influence the appropriate application [45-47].

A country must provide the community with health programs, facilities, goods, and services in sufficient quantities. Different levels of development in a country are indicators of the fulfillment of service and goods facilities. However, including certain factors such as hospitals, adequate drinking water, available sanitation, and other structures makes it health-related. As is in line with the World Health Organization (WHO) statement, professional and experienced medical personnel with good treatment and competitive salaries [48-50].

Health facilities, goods, and services must be available to everyone, especially marginalized or underserved groups, without discrimination and safe for marginalized or underserved groups. The environment must be accessible to vulnerable groups, especially ethnic groups. Minority groups, remote groups, women, children, people with disabilities, and people living with HIV/AIDS. Accessibility also means having physical access to health services and determinants of health, such as safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, even in remote areas [51, 52].

Accessibility also includes access to buildings for people with disabilities. Health facilities, goods, and services must be affordable for everyone. Payment for health services and services related to the determinants of health is based on the principle of equity, ensuring that these services are affordable for everyone, including disadvantaged groups in society, both in the private and government sectors. To achieve equality, poor people do not bear the burden of health service costs disproportionate to those of rich people. Access includes the right to seek, receive, and disseminate information and ideas about health issues [53, 54]. However, access to information is as important as the right to confidentiality of health data. All health facilities, products, and services must be acceptable based on medical ethics and culturally sensitive, including respect for the cultures of individuals, minorities, groups, and communities and considering gender and the life cycle. This supplement also aims to improve the health of those in need while maintaining the confidentiality of their health condition [55-58].

Healthcare facilities, products, and services must be culturally acceptable, medically sound, and of high quality. This requires competent staff, medical supplies, hospital equipment with scientifically approved expiration dates, safe and potable drinking water, and adequate sanitation. Along with food, clothing, and shelter, health is a basic human need. Human life is meaningless without a healthy life because sick people cannot carry out their daily activities well. Aside from that, sick people (patients) who cannot cure their disease on their own have no choice but to seek assistance from health workers who can cure their disease, and these health workers will carry out what is known as health efforts by providing health services.

A good health index for its citizens is one of the most important elements of a country's development; as a result, every country must have a system for regulating the implementation of the health sector so that the goal of making society healthy is achieved. This regulatory system is outlined in statutory regulations, which can later be used as legal guidelines for providing citizens with health care services [59-62].

As a result, understanding health law is critical not only for health professionals and the general public as healthcare consumers but also for academics and legal practitioners. Understanding medical law is very important so that health workers can provide medical services based on established procedures and use knowledge of medical law to correct medical errors in medical practice. The terms health law and medical law are often used interchangeably. This is because health law courses at various law faculties in Indonesia usually only cover issues related to medicine and discuss medical law or medical law.

The health law is currently divided into Public Health Law and Medical Law. All cover medical services, although public health laws prioritize public health services or hospital medical services, and medicine laws prioritize or regulate medical services for individuals or just one person [63-67].

Health care laws, including lexspecialis laws, specifically protect the obligations of health care professionals and the obligations of health care recipients in human health service programs designed to achieve the goals of the Health for All Declaration. This health law regulates the rights and obligations of all service providers and recipients, individuals (patients), and community groups. Health law exists not only in one form of regulation but also in various regulations and laws. Some relate to criminal, civil, and administrative law, while others relate to the application, interpretation, and evaluation of problems in the health and medical fields [68-70].

Following the law's goals, the law serves an important function in protecting and maintaining order and peace in society. According to legal principles, the function of law is to ensure that health development provides the greatest benefit to humanity and life to providers and recipients of health services. With adequate funding, the health administration must be able to provide fair and equitable services to all levels of society [71-74].

In general, the function of this law is to protect the legal aspects of every person or party in various areas of life. In other words, we want to provide legal protection if legal issues arise in social life. The function of law is summed up as protecting and maintaining order and tranquility. A law dealing with medical/health problems is required for its function as a social engineering tool (controlling whether the law has been followed in accordance with its objectives). Because this legal function applies generally, it also applies to health and medical law. From a human rights perspective, the right to health is often classified as a second and third-generation human right. Regarding individual health, the right to health is part of economic, social, and cultural rights. When it comes to public health, it is included in the right to development. Collective rights based on solidarity and brotherhood are included in third-generation human rights. These human rights include the right to development, peace, and a healthy and balanced living environment [75-78].

Understanding the three types of human rights must not be fragmented, as this will result in quality stratification. Although the intention is only to facilitate identification, human rights treatment must be universal, independent, and interdependent.

Since health is recognized as a human right, its application can take on a variety of meanings. This is inextricably linked to the concept of health. According to Health Law Number 23 of 1992, health is a state of physical, mental, and social well-being that allows every person to live a socially and economically productive life. This broad understanding impacts the perception of health as a human right [79-81].

Article 4 of the Law emphasizes that everyone has the same right to optimal health, while Article 28H of the 1945 Constitution confirms everyone's right to health care. The sentences obtaining a health degree and obtaining health services have different meanings. There is a perception that obtaining a degree of health has a broader meaning than "obtaining health services" because obtaining health services is part of the right to obtain a degree of health under this law. However, it cannot be said hastily that the constitution's protection of human rights in the health sector is narrower than that regulated by Law Number 23 of 1992.

The health literature refers to human rights in the health sector using various terms, such as the human right to health, the right to health, or the right to obtain optimal health.

The law is concerned with the meaning of terms rather than the terms themselves. Furthermore, since the 1945 Constitution established constitutional guarantees for the right to health, correctly recognizing this right has become critical for the law. In accordance with their dynamic development, human rights tend to give birth to new rights or give rise to new meanings. The right to health was initially limited to medical services but was later expanded to include various aspects of individual, community, and environmental health [82-84].

The right to health as a human right is a genre that is a collection of certain rights. In general, the welfare state is an ideal development model that focuses on increasing welfare by giving the state a greater role in providing universal and comprehensive social services to its citizens. The state is the highest organization of several groups of people who live together in a certain area and want a sovereign government. Prosperity refers to the happiness of society and individuals. Social happiness refers to an individual's overall happiness as a member of society. Welfare, in this case, refers to the welfare of society. Personal happiness is happiness that concerns the soul. An individual results from income, wealth, and other economic factors [85, 86].

The welfare state aims to free citizens from dependence on market mechanisms (decommodification) by making welfare a right for all citizens and to achieve this through state social policy instruments. According to the evolution of international human rights law, fulfilling the need for the right to health is the responsibility of each country's government.

As a result, as explained in articles 14 to 20 of Law 36 of 2009 concerning Health, each country's government is obligated to provide the right to health to its people. Because health is an indicator of a nation's level of human welfare, it becomes a national development priority. The availability of medicines as part of public health services is a critical component of health. This is because drugs save lives and restore or maintain health.

Medicine is an important component of health services because it is required in most health efforts. People increasingly demand high-quality and professional health services, including drug services, as public awareness and health knowledge have grown. As a result, health is the foundation for determining humanity's level. When a person lacks health, he or she becomes conditionally unequal. Without health, a person cannot exercise his other rights. Unhealthy people, by definition, have limited rights to life, cannot obtain and do decent work, do not have the right to organize, collect, and express opinions, and cannot continue to carry out their functions. In other words, humans can't enjoy life to the fullest.

Internationally, the importance of health as a human right and a necessary condition for fulfilling other rights has been recognized. The right to health includes the right to live and work in a healthy environment, health care, and special consideration for the health of mothers and children. According to Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, everyone has the right to a standard of living consistent with the health and welfare of himself and his family, including the right to food, clothing and shelter, the health and welfare of his family; health care and the right to feel safe when unemployed.

The principle of democracy, which states that the government has the responsibility to protect the rights of its citizens, is the main basis for the government's obligation to protect human rights.

Furthermore, the concept of the welfare state as a modern state concept led to the expansion of state autonomy. This power has the sole aim of promoting and achieving the realization of human rights. The state no longer only has to ensure that individual rights are not violated but also has to try to enforce those rights. The state must also fulfill the right to health. The government's obligation to protect the right to health as a human right is based on international law in Article 2, Part 1 of the Convention and Article 28I, Part 4 of the 1945 Constitution, and the state, especially the government, has an obligation to protect human rights.

The right to health and the responsibility to promote, protect and activate it. Article 8 of the Human Rights Law emphasizes the government's obligations. Article 7 of the health law states that the government is responsible for implementing health service initiatives that are fair and affordable for the community. According to Article 9 of the health law, the government is responsible for improving public health. Efforts to protect the right to health can take various forms, including prevention and treatment. Efforts to prevent this include creating a healthy environment, ensuring the availability of food and employment opportunities, and ensuring good housing and a healthy environment. Meanwhile, healing efforts are carried out by providing optimal medical services.

Health services include social protection, adequate health facilities, qualified health workers, and affordable public service financing. Article 12 of the Convention sets out the steps to achieve the highest level of physical and mental health. Provisions to reduce stillbirths and promote the healthy development of children include environmental and occupational health, as well as all aspects of prevention, treatment, and control of all infectious diseases, occupational diseases, and other endemic diseases.

The health law does not regulate various government initiatives to achieve optimal health. In general, health law regulates health maintenance, health promotion (promotion), disease prevention (prevention), disease treatment (treatment), and health restoration (rehabilitation) approaches that must be used to achieve health goals. The optimal level of health for society must be implemented in a comprehensive, integrated and sustainable manner.

The Department of Health has launched a Healthy Indonesia campaign. It is hoped that ideal health conditions will be attained. According to the Ministry of Health data, several improvements have recently been made in the health sector. Life expectancy had risen to 66 years in 2000, up from 46 years in the 1960s. The birth rate per 1000 live birth babies decreased to 45 babies who died, down from 55 babies in 1995.

In terms of health care, almost every sub-district had a community health center in 2000. Approximately 20,000 doctors and 5,000 dentists have been assigned to it. Village midwives have increased to 54,956, and 20,000 Polindes (village polyclinics) have been built with community help. Various other advancements have also been made to realize and fulfill the public's right to health as part of human rights fulfillment.

However, despite various accomplishments, we are confronted with numerous challenges. The main challenge is the Indonesian people's condition, which is still in crisis, making it difficult to obtain good health services. Poverty is the number one enemy of health. This condition is exacerbated by the health trend as an industry that frequently overlooks the aspect of health as a humanitarian service. Health is an expensive commodity. Furthermore, it appears that policymakers are not yet committed to their responsibilities in terms of health. This is demonstrated by the low level of funding allocated to the health sector, both in terms of facilities and infrastructure, as well as social security for health services.

People currently have to pay a high price for good health care, and low-income people frequently do not have access to adequate health care. Several incidents demonstrate that a hospital's profit orientation can precede humanity. Even in critical condition, a patient must sometimes complete various financial requirements and bureaucracy before receiving services, and the patient may die as a result.

Both the private and public sectors can provide health services. Private services are generally of higher quality but are more expensive and, in some cases, unaffordable. Meanwhile, government services are less expensive but of lower quality. However, the principle that must be followed is that health care must remain oriented toward humanitarian services, which the government must provide. When a crisis or shortage occurs, policymakers are always faced with confusion.

However, if health is recognized as the most important foundation for human dignity and the survival of generations, then concrete policies and steps must be taken to realize the right to health as a human right. The right to health is recognized by international human rights law. The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights is widely recognized as the most important instrument for protecting the right to health [87-92]. This Convention establishes the highest physical and mental health standards attainable by all people and recognizes the right to enjoy these rights. It's worth noting that Covenant places equal emphasis on mental and physical health, which is often overlooked. Aside from that, human rights are rights naturally attached to living creatures called humans solely because they are humans, not other creatures. This right is inherent in a human being once it is truly present. These human rights are inextricably linked to human dignity. Humans cannot live with dignity and worth without these fundamental rights. Individuals and society benefit from fulfillment and respect for human rights.

This study was also restricted to information gathered from veterans of war. Direct data or information from war veterans will be extremely beneficial to education. The study questionnaire asks about Indonesian war veterans' understanding of the UDHR ideals and how applying them can lead to more practical outcomes and efficient solutions. It is hoped that such studies will answer queries about human rights in the medical field.

Conclusion

The gradual realization of universal access to high-quality and affordable health facilities in the shortest possible time indicates that the right to health is being realized. The principles of availability, affordability, acceptability, and quality must be followed in implementing the right to health. To ensure the realization of the right to health, the state must be responsible and involve all relevant stakeholders, including the general public and non-governmental organizations. These organizations must be able to increase awareness and carry out consistent monitoring and evaluation.

Acknowledgments: No acknowledgment is mentioned by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: The Research Ethics Committee of Universitas PGRI Semarang has approved all stages of the research. All research procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflicts of Interests: There are no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Maryanto (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Data Analyst (70%); Nur Azis Rohmansyah (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Human rights also include the health of every person, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, religion, or nationality, and the right to accessible and acceptable medical services, medicines, and medical equipment. The right to health follows the principle of “progressive realization” [1-3], where the state is not allowed to take regressive steps and is obliged to realize the right to health [4-6].

The progressive realization also means that countries must regularly monitor how the right to health is realized and assess whether they have made sufficient progress given the available resources [7-9]. Therefore, monitoring health rights requires appropriate indicators based on human rights principles.

It is true, as can be seen by observing and paying attention to the aforementioned provisions, that every disruption, intervention, unfairness, and apathy, in whatever form, leads to unhealthy human bodies and minds, as well as unhealthy natural and social environments, laws and regulations, and unhealthiness. The social management justice they are provided violates both their human and legal rights [10-14].

The right to health does not imply that everyone must be healthy or that the government must provide ostentatious medical facilities beyond its means. However, increasing pressures are on the government and public authorities to develop policies and work plans that would result in the availability and affordability of healthcare facilities for everyone in the shortest time [15-17].

Although the right to health as a right of every person is stated in the International Covenant, it does not include health services. However, the history of the drafting and grammatical interpretation of this law, which stipulates that the measures to be taken by states parties to the present Covenant to realize this rightfully, must include the following: measures to reduce stillbirth and child death while promoting the healthy development of children, improving occupational and environmental health aspects, including all infectious diseases with prevention, management, and control [18-20].

Human rights and health have a mutual influence (Figure 1). Human rights violations are also violations of the right to health. The government fails if it does not fulfill its obligations to human rights and health, as seen in the bottom right circle. Meanwhile, the upper class is closely related to the right to health, which is violated by violent practices that also violate civil and political rights. The bottom left circle depicts the relationship between human rights and health due to vulnerable social conditions [21, 22].

Figure 1. Mutual influence of human rights and health

In the meantime, several aspects of the relationship between the State and Individuals cannot be addressed alone. In particular, the State cannot ensure good health or offer protection from all potential disease causes in humans. In the meantime, several aspects of the relationship between the State and Individuals cannot be addressed alone. The State, in particular, cannot guarantee good health or protection against all potential causes of human disease. Individual risk factors for disease, as well as the adoption of risky or unhealthy lifestyles, all significantly impact an individual's health. As a result, it is critical to understand that the right to health includes the right to receive various facilities, services, and conditions necessary for attaining reasonable and sufficient health standards [23-27].

Human rights, including the right to health, have been widely recognized. However, to our knowledge, no research has been conducted on how veterans understand their right to health. We conducted a comprehensive survey to determine how well veterans understand and apply the principles underlying the right to health. Since introducing the normative principles, we have documented efforts to assess the implementation of the right to health. This study aimed to identify efforts in the public health literature to evaluate the implementation of war veterans' human rights to health.

Information and Methods

This systematic review was conducted on the global literature on the right to health or human rights-based approaches to war veterans' health.

PRISMA guidelines for Grant and Booth typology of reviews as systematic reviews and “scoping reviews” [8, 28, 29]. Various databases, including Global Health, Embase, Medline, Pubmed, and Open Grey, were utilized to gather the relevant studies. The retrieval process focused on keywords like “right to health” and “human rights-based approaches to health”. Secondary data sources and library research methods were used in this study, focusing on the government, non-governmental organizations, civil society, and intergovernmental organizations involved in human rights enforcement. This methodology is utilized because there are a lot of corroborating secondary sources. Hence, the government's websites and reports can also be used to learn about its initiatives to uphold and defend human rights under the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In the meantime, the authors were able to locate comments from state commissions from outside actors, as well as journals, articles, newspapers, reports, and INGO websites.

The database search produced 6250 studies by checking the full text and then filtering the titles and abstracts, resulting in 66 studies, which were then included in the analysis and obtained 29 studies, with the majority of research references being general [30-32], namely the right to health included in the health and human system; an update of scientific indicators for the right to health; and the right to health assessments that use innovative methods. These studies were mainly applied in the fields of maternal and reproductive and child health, tuberculosis, and HIV in war veterans [33-35] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PRISMA flowchart of the study

Findings

121 studies were collected from various databases that examined human rights to health practices or how to measure them. 66 studies (54.5%) which established new frameworks for assessing the human right to health implementation, applying new indicators to evaluate and assess whether policies and programs fall under the human right to health. Finally, 29 studies used health indicators in implementing the human right to health by referring to cases based on laws, policies, and programs [36-41]. A bibliographic search was used to find interdisciplinary health and human rights journal studies. These studies help differentiate how the right to health is discussed and evaluated in the public health and human rights literature (Table 1).

Table 1. Extracted data from the final documents

Discussion

This study aimed to identify efforts in the public health literature to evaluate the implementation of war veterans' human rights to health. This review included the following 78 studies. Veterans' right to health was not adequately addressed in public health research. Research often focuses on physical availability, access to medicines and healthS services, and measures of disaggregated health outcomes. Human rights policy does not address the right to health, despite some public health research indicating a link between health outcomes and human rights. In the field of public health, the sources of the right to health are well known.

Health is a subjective concept that encompasses a wide range of factors, such as socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic context. As a result, defining what is covered by the right to health is difficult. Experts, activists, and UN agencies are attempting to provide information about the essential elements of the right to health. The following components comprise core content, a set of requirements that must always be met, regardless of resource availability:

1) Health care includes immunization, appropriate treatment for common illnesses and accidents, and the distribution of basic medicines. Health care for mothers and children, including family planning; and

2) Basic health prerequisites include promoting appropriate food and nutrition, providing clean water and basic sanitation, and educating people about health issues and how to prevent and control them.

The aforementioned elements cannot be fully classified when examining the relationship between health and human rights. This means that the right to health does not necessitate adding health-related elements already covered by other human rights [13-15, 17, 22].

Meanwhile, the right to health is broadly defined by characterizing the contents of this right:

1) Reducing the mortality rate of infants and children under the age of five; sexual and reproductive health services; reproductive health access and resources; access to family planning; and emergency services in the field of obstetrics;

2) The right to a safe and healthy working environment, including clean drinking water, preventive measures against occupational diseases and accidents, and basic sanitation that prevents harmful substances such as radiation, chemicals, and environmental hazards. Industrial sanitation ensures adequate food and nutritional supplies, a clean and sanitary work environment, and adequate and safe housing. It prevents the use of alcohol, tobacco, drugs, and other harmful substances;

3) The right to prevent, control, and investigate diseases, including occupational diseases and endemic and epidemic diseases; the development of prevention initiatives and behavioral education related to health, sexual and reproductive health, including efforts to address HIV/AIDS, STDs, and improving social determinants of health, such as gender equality, education, economic growth, a safe environment, and assistance from natural disasters;

4) The right to goods, services, and facilities for health: ensuring the provision of medical services that encompass preventive, curative, promotive, and rehabilitative measures for the body and mind; supply of necessary medications; appropriate psychiatric medicine or care; increasing community participation in health initiatives such as insurance programs, health sector organizations, and, in particular, national and international political decision-making; and

5) Some specific topics and broader applications are the gender perspective, elder care, people with disabilities, children and adolescents' health, non-discrimination and equal treatment, and indigenous communities.

As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed health indicators to assess the development, implementation, and fulfillment of health-related rights. This commitment is also binding on Indonesia, which has established 50 health indicators that must be met [42].

To ensure human rights regarding the right to health, the state fulfills its obligations guided by the following principles:

1) The state must provide various health services to the entire population;

2) The state must provide health facilities, goods, and services within its jurisdiction for all people without discrimination, physical access, economic access, and information access to seek, receive, and/or disseminate information and ideas regarding health issues;

3) Medical ethics is used in all health facilities, goods, and services and is culturally appropriate; and

4) A scientific and medical viewpoint is used in all health products, facilities, and services and is culturally acceptable to protect the confidentiality of health status information. This includes, among other things, medically trained personnel, legally approved medications, and unexpired scientific and hospital equipment while improving the health of those in need.

Meanwhile, the three types of state obligations to protect the right to health are as follows:

1) The state's primary concern within this framework is "what will not be done" or "what will be avoided" in terms of policies or actions. States must exercise restraint and refrain from taking any actions that could harm public health. Examples of such actions include not enacting laws that restrict access to healthcare services, not discriminating, not concealing or distorting vital health information, refusing to accept international agreements without first weighing the potential effects on the right to health, and not distributing dangerous medications;

2) The state's primary duty is to enact laws or take other measures that ensure equitable access to health services from outside providers. Laws, standards, regulations, and guidelines should be created to safeguard employees, society, and the environment. Control and regulate traditional healing methods that are known to be harmful to health, as well as the marketing and distribution of substances that are harmful to health, such as alcohol, tobacco, and others; and

3) The government's responsibilities in this situation include providing health facilities and services, adequate food, health-related information and education, services for pre-existing conditions, and social factors that affect health, such as gender equality, equal access to employment, and children's rights. Identity, education, a lack of exploitation or violence, and sexual offenses that harm health are all important considerations.

States must take human rights steps toward fulfilling the right to health to gradually achieve the full realization of this right for war veterans, as mandated in the International Covenant [43, 44].

The right to health is an inseparable part of one of the fundamental human rights and a basic need that cannot be compromised under any circumstances. Therefore, regardless of religion, ethnicity, economic situation, social situation, and political background, the state should be able to fulfill the right to health as one of the basic rights of every individual that must be respected. The right to health is included in the family of economic, social, and cultural rights but intersects with civil and political rights. Health, as a human right, is a broad subject. Various expert opinions support the link. Human rights and health are interconnected approaches that complement the concept of human well-being. The right to health, in all its forms and at all levels, contains important and interconnected elements. Local conditions will greatly influence the appropriate application [45-47].

A country must provide the community with health programs, facilities, goods, and services in sufficient quantities. Different levels of development in a country are indicators of the fulfillment of service and goods facilities. However, including certain factors such as hospitals, adequate drinking water, available sanitation, and other structures makes it health-related. As is in line with the World Health Organization (WHO) statement, professional and experienced medical personnel with good treatment and competitive salaries [48-50].

Health facilities, goods, and services must be available to everyone, especially marginalized or underserved groups, without discrimination and safe for marginalized or underserved groups. The environment must be accessible to vulnerable groups, especially ethnic groups. Minority groups, remote groups, women, children, people with disabilities, and people living with HIV/AIDS. Accessibility also means having physical access to health services and determinants of health, such as safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, even in remote areas [51, 52].

Accessibility also includes access to buildings for people with disabilities. Health facilities, goods, and services must be affordable for everyone. Payment for health services and services related to the determinants of health is based on the principle of equity, ensuring that these services are affordable for everyone, including disadvantaged groups in society, both in the private and government sectors. To achieve equality, poor people do not bear the burden of health service costs disproportionate to those of rich people. Access includes the right to seek, receive, and disseminate information and ideas about health issues [53, 54]. However, access to information is as important as the right to confidentiality of health data. All health facilities, products, and services must be acceptable based on medical ethics and culturally sensitive, including respect for the cultures of individuals, minorities, groups, and communities and considering gender and the life cycle. This supplement also aims to improve the health of those in need while maintaining the confidentiality of their health condition [55-58].

Healthcare facilities, products, and services must be culturally acceptable, medically sound, and of high quality. This requires competent staff, medical supplies, hospital equipment with scientifically approved expiration dates, safe and potable drinking water, and adequate sanitation. Along with food, clothing, and shelter, health is a basic human need. Human life is meaningless without a healthy life because sick people cannot carry out their daily activities well. Aside from that, sick people (patients) who cannot cure their disease on their own have no choice but to seek assistance from health workers who can cure their disease, and these health workers will carry out what is known as health efforts by providing health services.

A good health index for its citizens is one of the most important elements of a country's development; as a result, every country must have a system for regulating the implementation of the health sector so that the goal of making society healthy is achieved. This regulatory system is outlined in statutory regulations, which can later be used as legal guidelines for providing citizens with health care services [59-62].

As a result, understanding health law is critical not only for health professionals and the general public as healthcare consumers but also for academics and legal practitioners. Understanding medical law is very important so that health workers can provide medical services based on established procedures and use knowledge of medical law to correct medical errors in medical practice. The terms health law and medical law are often used interchangeably. This is because health law courses at various law faculties in Indonesia usually only cover issues related to medicine and discuss medical law or medical law.

The health law is currently divided into Public Health Law and Medical Law. All cover medical services, although public health laws prioritize public health services or hospital medical services, and medicine laws prioritize or regulate medical services for individuals or just one person [63-67].

Health care laws, including lexspecialis laws, specifically protect the obligations of health care professionals and the obligations of health care recipients in human health service programs designed to achieve the goals of the Health for All Declaration. This health law regulates the rights and obligations of all service providers and recipients, individuals (patients), and community groups. Health law exists not only in one form of regulation but also in various regulations and laws. Some relate to criminal, civil, and administrative law, while others relate to the application, interpretation, and evaluation of problems in the health and medical fields [68-70].

Following the law's goals, the law serves an important function in protecting and maintaining order and peace in society. According to legal principles, the function of law is to ensure that health development provides the greatest benefit to humanity and life to providers and recipients of health services. With adequate funding, the health administration must be able to provide fair and equitable services to all levels of society [71-74].

In general, the function of this law is to protect the legal aspects of every person or party in various areas of life. In other words, we want to provide legal protection if legal issues arise in social life. The function of law is summed up as protecting and maintaining order and tranquility. A law dealing with medical/health problems is required for its function as a social engineering tool (controlling whether the law has been followed in accordance with its objectives). Because this legal function applies generally, it also applies to health and medical law. From a human rights perspective, the right to health is often classified as a second and third-generation human right. Regarding individual health, the right to health is part of economic, social, and cultural rights. When it comes to public health, it is included in the right to development. Collective rights based on solidarity and brotherhood are included in third-generation human rights. These human rights include the right to development, peace, and a healthy and balanced living environment [75-78].

Understanding the three types of human rights must not be fragmented, as this will result in quality stratification. Although the intention is only to facilitate identification, human rights treatment must be universal, independent, and interdependent.

Since health is recognized as a human right, its application can take on a variety of meanings. This is inextricably linked to the concept of health. According to Health Law Number 23 of 1992, health is a state of physical, mental, and social well-being that allows every person to live a socially and economically productive life. This broad understanding impacts the perception of health as a human right [79-81].

Article 4 of the Law emphasizes that everyone has the same right to optimal health, while Article 28H of the 1945 Constitution confirms everyone's right to health care. The sentences obtaining a health degree and obtaining health services have different meanings. There is a perception that obtaining a degree of health has a broader meaning than "obtaining health services" because obtaining health services is part of the right to obtain a degree of health under this law. However, it cannot be said hastily that the constitution's protection of human rights in the health sector is narrower than that regulated by Law Number 23 of 1992.

The health literature refers to human rights in the health sector using various terms, such as the human right to health, the right to health, or the right to obtain optimal health.

The law is concerned with the meaning of terms rather than the terms themselves. Furthermore, since the 1945 Constitution established constitutional guarantees for the right to health, correctly recognizing this right has become critical for the law. In accordance with their dynamic development, human rights tend to give birth to new rights or give rise to new meanings. The right to health was initially limited to medical services but was later expanded to include various aspects of individual, community, and environmental health [82-84].

The right to health as a human right is a genre that is a collection of certain rights. In general, the welfare state is an ideal development model that focuses on increasing welfare by giving the state a greater role in providing universal and comprehensive social services to its citizens. The state is the highest organization of several groups of people who live together in a certain area and want a sovereign government. Prosperity refers to the happiness of society and individuals. Social happiness refers to an individual's overall happiness as a member of society. Welfare, in this case, refers to the welfare of society. Personal happiness is happiness that concerns the soul. An individual results from income, wealth, and other economic factors [85, 86].

The welfare state aims to free citizens from dependence on market mechanisms (decommodification) by making welfare a right for all citizens and to achieve this through state social policy instruments. According to the evolution of international human rights law, fulfilling the need for the right to health is the responsibility of each country's government.

As a result, as explained in articles 14 to 20 of Law 36 of 2009 concerning Health, each country's government is obligated to provide the right to health to its people. Because health is an indicator of a nation's level of human welfare, it becomes a national development priority. The availability of medicines as part of public health services is a critical component of health. This is because drugs save lives and restore or maintain health.

Medicine is an important component of health services because it is required in most health efforts. People increasingly demand high-quality and professional health services, including drug services, as public awareness and health knowledge have grown. As a result, health is the foundation for determining humanity's level. When a person lacks health, he or she becomes conditionally unequal. Without health, a person cannot exercise his other rights. Unhealthy people, by definition, have limited rights to life, cannot obtain and do decent work, do not have the right to organize, collect, and express opinions, and cannot continue to carry out their functions. In other words, humans can't enjoy life to the fullest.

Internationally, the importance of health as a human right and a necessary condition for fulfilling other rights has been recognized. The right to health includes the right to live and work in a healthy environment, health care, and special consideration for the health of mothers and children. According to Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, everyone has the right to a standard of living consistent with the health and welfare of himself and his family, including the right to food, clothing and shelter, the health and welfare of his family; health care and the right to feel safe when unemployed.

The principle of democracy, which states that the government has the responsibility to protect the rights of its citizens, is the main basis for the government's obligation to protect human rights.

Furthermore, the concept of the welfare state as a modern state concept led to the expansion of state autonomy. This power has the sole aim of promoting and achieving the realization of human rights. The state no longer only has to ensure that individual rights are not violated but also has to try to enforce those rights. The state must also fulfill the right to health. The government's obligation to protect the right to health as a human right is based on international law in Article 2, Part 1 of the Convention and Article 28I, Part 4 of the 1945 Constitution, and the state, especially the government, has an obligation to protect human rights.

The right to health and the responsibility to promote, protect and activate it. Article 8 of the Human Rights Law emphasizes the government's obligations. Article 7 of the health law states that the government is responsible for implementing health service initiatives that are fair and affordable for the community. According to Article 9 of the health law, the government is responsible for improving public health. Efforts to protect the right to health can take various forms, including prevention and treatment. Efforts to prevent this include creating a healthy environment, ensuring the availability of food and employment opportunities, and ensuring good housing and a healthy environment. Meanwhile, healing efforts are carried out by providing optimal medical services.

Health services include social protection, adequate health facilities, qualified health workers, and affordable public service financing. Article 12 of the Convention sets out the steps to achieve the highest level of physical and mental health. Provisions to reduce stillbirths and promote the healthy development of children include environmental and occupational health, as well as all aspects of prevention, treatment, and control of all infectious diseases, occupational diseases, and other endemic diseases.

The health law does not regulate various government initiatives to achieve optimal health. In general, health law regulates health maintenance, health promotion (promotion), disease prevention (prevention), disease treatment (treatment), and health restoration (rehabilitation) approaches that must be used to achieve health goals. The optimal level of health for society must be implemented in a comprehensive, integrated and sustainable manner.

The Department of Health has launched a Healthy Indonesia campaign. It is hoped that ideal health conditions will be attained. According to the Ministry of Health data, several improvements have recently been made in the health sector. Life expectancy had risen to 66 years in 2000, up from 46 years in the 1960s. The birth rate per 1000 live birth babies decreased to 45 babies who died, down from 55 babies in 1995.

In terms of health care, almost every sub-district had a community health center in 2000. Approximately 20,000 doctors and 5,000 dentists have been assigned to it. Village midwives have increased to 54,956, and 20,000 Polindes (village polyclinics) have been built with community help. Various other advancements have also been made to realize and fulfill the public's right to health as part of human rights fulfillment.

However, despite various accomplishments, we are confronted with numerous challenges. The main challenge is the Indonesian people's condition, which is still in crisis, making it difficult to obtain good health services. Poverty is the number one enemy of health. This condition is exacerbated by the health trend as an industry that frequently overlooks the aspect of health as a humanitarian service. Health is an expensive commodity. Furthermore, it appears that policymakers are not yet committed to their responsibilities in terms of health. This is demonstrated by the low level of funding allocated to the health sector, both in terms of facilities and infrastructure, as well as social security for health services.

People currently have to pay a high price for good health care, and low-income people frequently do not have access to adequate health care. Several incidents demonstrate that a hospital's profit orientation can precede humanity. Even in critical condition, a patient must sometimes complete various financial requirements and bureaucracy before receiving services, and the patient may die as a result.

Both the private and public sectors can provide health services. Private services are generally of higher quality but are more expensive and, in some cases, unaffordable. Meanwhile, government services are less expensive but of lower quality. However, the principle that must be followed is that health care must remain oriented toward humanitarian services, which the government must provide. When a crisis or shortage occurs, policymakers are always faced with confusion.

However, if health is recognized as the most important foundation for human dignity and the survival of generations, then concrete policies and steps must be taken to realize the right to health as a human right. The right to health is recognized by international human rights law. The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights is widely recognized as the most important instrument for protecting the right to health [87-92]. This Convention establishes the highest physical and mental health standards attainable by all people and recognizes the right to enjoy these rights. It's worth noting that Covenant places equal emphasis on mental and physical health, which is often overlooked. Aside from that, human rights are rights naturally attached to living creatures called humans solely because they are humans, not other creatures. This right is inherent in a human being once it is truly present. These human rights are inextricably linked to human dignity. Humans cannot live with dignity and worth without these fundamental rights. Individuals and society benefit from fulfillment and respect for human rights.

This study was also restricted to information gathered from veterans of war. Direct data or information from war veterans will be extremely beneficial to education. The study questionnaire asks about Indonesian war veterans' understanding of the UDHR ideals and how applying them can lead to more practical outcomes and efficient solutions. It is hoped that such studies will answer queries about human rights in the medical field.

Conclusion

The gradual realization of universal access to high-quality and affordable health facilities in the shortest possible time indicates that the right to health is being realized. The principles of availability, affordability, acceptability, and quality must be followed in implementing the right to health. To ensure the realization of the right to health, the state must be responsible and involve all relevant stakeholders, including the general public and non-governmental organizations. These organizations must be able to increase awareness and carry out consistent monitoring and evaluation.

Acknowledgments: No acknowledgment is mentioned by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: The Research Ethics Committee of Universitas PGRI Semarang has approved all stages of the research. All research procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflicts of Interests: There are no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Maryanto (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Data Analyst (70%); Nur Azis Rohmansyah (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%)

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Keywords:

References

1. Haldız AC. The optional protocol to the international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Eur J Multidiscip Stud. 2017;2(6):37-44. [Link] [DOI:10.26417/ejms.v6i1.p37-44]

2. Zysset A, Scherz A. Proportionality as procedure: Strengthening the legitimate authority of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Glob Const. 2021;10(3):524-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S2045381721000071]

3. Tineke D. Linking discourse and practice: the human rights-based approach to development in the village assaini program in the kongo central. Hum Rights Quart. 2016;38(3):787-813. [Link] [DOI:10.1353/hrq.2016.0042]

4. Rodgers PA. Designing work with people living with dementia: Reflecting on a decade of research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):11742. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182211742]

5. Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Męczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, Grymowicz M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020;139:6-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.018]

6. Mathers CD. History of the global burden of disease assessment at the World Health Organization. Arch Public Health. 2020;78:77. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13690-020-00458-3]

7. Hannah M. Rejecting Rights-Based Approaches to Development: Alternative Engagements with Human Rights. J Hum Rights. 2017;16(1): 61-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14754835.2015.1103161]

8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097]

9. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91-108. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x]

10. Meade V. Embracing diverse women veteran narratives: Intersectionality and women veteran's identity. J Veterans Stud. 2020;6(3):47-53. [Link] [DOI:10.21061/jvs.v6i3.218]

11. Hoyt T, Renshaw KD. Emotional disclosure and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Veteran and spouse reports. Int J Stress Manag. 2014;21(2):186-206. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0035162]

12. Gasparri G, Tcholakov Y, Gepp S, Guerreschi A, Ayowole D, Okwudili ÉD, et al. Integrating youth perspectives: Adopting a human rights and public health approach to climate action. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4840. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19084840]

13. Sundler AJ, Darcy L, Råberus A, Holmström IK. Unmet health-care needs and human rights-A qualitative analysis of patients' complaints in light of the right to health and health care. Health Expect. 2020;23(3):614-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/hex.13038]

14. Chapman AR. Assessing the universal health coverage target in the sustainable development goals from a human rights perspective. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16:33. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12914-016-0106-y]

15. Mahomed F. Addressing the problem of severe underinvestment in mental health and well-being from a human rights perspective. Health Hum Rights J. 2020;22(1):35-50. [Link]

16. Grugel J, Masefield SC, Msosa A. The human right to health, inclusion, and essential health care packages in low income countries: "health for all" in Malawi. Int J Hum Rights Healthc. 2022;17(1):75-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/IJHRH-09-2021-0178]

17. Chapman AR. Evaluating the health-related targets in the sustainable development goals from a human rights perspective. Int J Hum Rights. 2017;21(8):1098-113. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13642987.2017.1348704]

18. Hamilton AB, Williams L, Washington DL. Military and mental health correlates of unemployment in a national sample of women veterans. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S32-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000297]

19. Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: Transformation of the veterans health care system. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:313-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090940]

20. Zerach G, Horesh D, Solomon Z. Secondary posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories and perceived health among spouses of war veterans: A 12-year longitudinal study. Psychol Health. 2022;37(6):675-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08870446.2021.1879807]

21. Danforth K, Ahmad AM, Blanchet K, Khalid M, Means AR, Memirie ST, et al. Monitoring and evaluating the implementation of essential packages of health services. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(Suppl1):e010726. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010726]

22. Chapman AR, Forman L, Lamprea E. Evaluating essential health packages from a human rights perspective. J Hum Rights. 2017;16(2):142-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14754835.2015.1107828]

23. Militaru A. Trauma Rehabilitation after war and conflict: Community and individual perspectives. Martz E, editor. Politikon: IAPSS J Polit Sci. 2015;26:168-70. [Link] [DOI:10.22151/politikon.26.12]

24. Friedman R. The group and the individual in conflict and war. Group Anal. 2010;43(3):281-300. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0533316410373440]

25. Suess Schwend A. Trans health care from a depathologization and human rights perspective. Public Health Rev. 2020;41:3. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40985-020-0118-y]

26. Birch M. From horror to hope: Recognizing and preventing the health impacts of war. Med Confl Surviv. 2022;38(4):355-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13623699.2022.2111758]

27. Fukuda-Parr S. Human rights and national poverty reduction strategies: Conceptual framework for human rights analysis of poverty reduction strategies and reviews of Guatemala, Liberia, and Nepal. SSRN Electronic J.2007. [Link] [DOI:10.2139/ssrn.2212836]

28. Gostin LO, Monahan JT, Kaldor J, DeBartolo M, Friedman EA, Gottschalk K, et al. The legal determinants of health: Harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1857-910. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30233-8]

29. Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099-104. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6]

30. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6]

31. Gruskin S, Ferguson L. Using indicators to determine the contribution of human rights to public health efforts. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(9):714-9. [Link] [DOI:10.2471/BLT.08.058321]

32. Barros de Luca G, Zopunyan V, Burke-Shyne N, Papikyan A, Amiryan D. Palliative care and human rights in patient care: An Armenia case study. Public Health Rev. 2017;38:18. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40985-017-0062-7]

33. Perehudoff K. Universal access to essential medicines as part of the right to health: A cross-national comparison of national laws, medicines policies, and health system indicators. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1699342. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/16549716.2019.1699342]

34. Yamin AE, Constantin A. A long and winding road: The evolution of applying human rights frameworks to health. Georget J Int Law. 2017;49(1):191-239. [Link]

35. D'Ambruoso L, Byass P, Qomariyah SN. Can the right to health inform public health planning in developing countries? A case study for maternal healthcare from Indonesia. Glob Health Action. 2008;1(1):1828. [Link] [DOI:10.3402/gha.v1i0.1828]

36. Hardee K, Kumar J, Newman K, Bakamjian L, Harris S, Rodríguez M, et al. Voluntary, human rights-based family planning: A conceptual framework. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45(1):1-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00373.x]

37. King EJ, Maman S, Wyckoff SC, Pierce MW, Groves AK. HIV testing for pregnant women: A rights-based analysis of national policies. Glob Public Health. 2013;8(3):326-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17441692.2012.745010]

38. Luh J, Cronk R, Bartram J. Assessing progress towards public health, human rights, and international development goals using frontier analysis. PLOS One. 2016;11(1):e0147663. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0147663]

39. Forman L, Brolan CE, Kenyon KH. Global health, human rights, and the law. Lancet. 2019;394(10213):1987. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32604-2]

40. Urueña R. Indicators as political spaces: Law, international organizations, and the quantitative challenge in global governance. Int Organ Law Rev. 2015;12(1):1-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1163/15723747-01201001]

41. Tuomisto K, Tiittala P, Keskimäki I, Helve O. Refugee crisis in Finland: Challenges to safeguarding the right to health for asylum seekers. Health Policy. 2019;123(9):825-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.07.014]

42. Blanchard M, Molina-Vicenty HD, Stein PK, Li X, Karlinsky J, Alpern R, et al. Medical correlates of chronic multisymptom illness in gulf war veterans. Am J Med. 2019;132(4):510-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.11.045]

43. Dekel R, Solomon Z, Horesh D. Predicting secondary posttraumatic stress symptoms among spouses of veterans: Veteran's distress or spouse's perception of that distress?. Psychol Trauma. 2023;15(Suppl 2):S409-17. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/tra0001182]

44. Van Hoof M. Military and veterans' mental health: Australian research in military and veterans' mental health. J Psychiatry. 2019;53(Suppl 1):83-5. [Link]

45. Gruskin S, Jardell W, Ferguson L, Zacharias K, Khosla R. Integrating human rights into sexual and reproductive health research: Moving beyond the rhetoric, what will it take to get us there?. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2021;29(1):367-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/26410397.2021.1881206]

46. Mitchell VA. The human rights key: An innovative tool for teaching health and human rights in the health sciences. Afr J Health Prof Educ. 2015;7(1):39-42. [Link] [DOI:10.7196/AJHPE.366]

47. Arulkumaran S. Health and human rights. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(1):4-13. [Link] [DOI:10.11622/smedj.2017003]

48. Logie CH, Perez-Brumer A, Parker R. The contested global politics of pleasure and danger: Sexuality, gender, health and human rights. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(5):651-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17441692.2021.1893373]

49. Meier BM, Gable L. Advancing the human right to health: Eleanor Kinney's seminal contributions to the development and implementation of human rights for public health. Ind Health Law Rev. 2020;17(1):21-32. [Link] [DOI:10.18060/25035]