Volume 14, Issue 4 (2022)

Iran J War Public Health 2022, 14(4): 391-400 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2022/04/19 | Accepted: 2022/07/25 | Published: 2022/11/1

Received: 2022/04/19 | Accepted: 2022/07/25 | Published: 2022/11/1

How to cite this article

Noferesti A, Behfar Z, Salehi K. Perception of Subjective Well-being in an Iranian Urban Population: A Phenomenological Study. Iran J War Public Health 2022; 14 (4) :391-400

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1150-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1150-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2- Shahid Hashemi Nezhad Pardis, University of Farhangian, Mashhad, Iran

3- Department of Curriculum Development & Instruction Methods, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2- Shahid Hashemi Nezhad Pardis, University of Farhangian, Mashhad, Iran

3- Department of Curriculum Development & Instruction Methods, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1095 Views)

Introduction

Subjective well-being refers to an overall evaluation of the quality of a person’s life from her/his own view. It represents the extent to which a person believes that her/his life affairs are going well [1, 2]. The evaluation of subjective well-being involves both the cognitive and emotional components. The cognitive aspect refers to the person’s general assessment of life events, while the emotional one involves the presence of positive emotions and the absence of negative feelings. A survey on well-being has suggested that positive emotions and life satisfaction are the most significant components of subjective well-being [3]. The findings of this survey reveal that people differentiate between happiness as a temporary emotional state and life satisfaction, which is an overarching assessment of one’s life. Indeed, subjective well-being is a deeper concept than the individual experience of being in a temporary pleasant mood. Since there is a vast wealth of literature on various aspects of well-being, we first present a brief review of recent literature on the most relevant aspect of the subject, followed by introducing the specific aim of this study. In recent years, numerous studies have suggested a strong link between well-being and desirable consequences, such as health and longevity [4-6], good job, high income [7, 8], desirable social interactions, and few or no negative feelings [9-11]. In most cultures, subjective well-being has been emphasized at both individual and social levels [12, 13].

Although some studies have suggested numerous key factors contributing to subjective well-being, others believe that the components of well-being vary across various cultures. For instance, 13118 college students in 31 country completed measures of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and satisfaction with specific domains, such as friends, family, and significant others [14]. The results of this study suggested that self-esteem was the most significant indicator of well-being and life satisfaction in such nations as the United States and New Zealand compared to older cultures like Egypt and Japan. Meanwhile, emotional support and pleasant relationships with others are indicators of well-being and life satisfaction in Hong Kong [15] and Japan [16].

A study by Parnami et al. in 2013, which was conducted on a sample of 400 adults in an Indian population, demonstrated that religion and community support were important determinants of enhancing one's perception of well-being [17]. Later in 2016, Delle Fave et al. studied a sample of 2799 adults from 11 countries and explored their definition of happiness [18]. This study used open-ended questions and asked the participants: “What is happiness for you?”. The answers encompassed various definitions addressing a broad range of life domains, from contextual and social domains to psychological areas. The analysis of the responses revealed that despite minimal variations in age and gender among the participants, emotional satisfaction from within predominated the psychological definitions, with family and social relationships being the second main contextual definitions.

In another qualitative study using a thematic analysis approach, thirty Indonesian adults participated in semi-structured interviews with a focus on their experience of well-being. The results of that study indicated that the fulfillment of basic needs, social relations, and the positive world views of self-acceptance, gratitude, and spirituality were the main aspects of subjective well-being [19]. The common interpretation of the above studies is that social relationship with family and community, as well as spirituality, played strong roles in the experience of well-being in Eastern cultures.

Further research in Iranian society is necessary, complementing the scarce literature in this field to increase our understanding of subjective well-being among Eastern cultures. Such a study should address the gap between the experience of subjective well-being and the individual definition and expectation of well-being within an Iranian population. The findings might be different from those known for Western nations and even for some Eastern cultures. Several earlier studies conducted in Iran focused on correlational variables associated with subjective well-being [20-22].

Not many well-focused studies have been conducted on this critical subject so far in Iran to date to explore the subjective definition of well-being. Interestingly, based on the latest World Happiness Report (2017), Iran ranked 105 among the 157 countries, with a subjective well-being score of 4.8. In this context, Iran, as the sixth most populous Muslim country, is an example of an Eastern developing nation with its own cultural, social and religious perspectives. Therefore, exploring the critical components of subjective well-being in Iran is a major challenge both for the people and the government. This study is an attempt to explore this subject and to contribute to overall plans aimed at enhancing the spirit of subjective well-being within the Iranian society.

Due to the current limitations facing research on well-being in Iran, we planned to use social interpretive instead of a theoretical framework in designing the present study. This interpretive approach encourages researchers to have an insight into human behavior and its interaction with society. This involves developing an in-depth understanding of people’s thoughts and beliefs about themselves and society [23]. As have been recommended by many researchers, such an understanding will be further enhanced if in-depth research is undertaken on the personal interpretations of well-being [18]. Such an in-depth qualitative and contextual approach necessitates gaining a thorough understanding of well-being at individual level and across cultures and the society, shedding light on socio-economic and cultural [19, 23]. This approach will help shedding light on how subjective well-being is evaluated and whether the current definitions of subjective well-being are culturally acceptable.

Well-being studies have little to offer about subjective well-being in Iranian society, with cultural differences compared to both the Eastern and Western nations. It justifies undertaking a descriptive phenomenological study as the framework, such as the one employed in this study [24]. Phenomenology is defined the study of lived experiences with a focus on discovery. We chose this method since it is based on describing particular phenomena or emergence of events as the individual experiences them throughout life [25]. In this descriptive method, researchers make no interpretations; rather, they analyze the descriptions verbalized by participants and group them into meaningful statements. Collecting the meanings are essential to the foundation of the phenomenon under study [26].

This study aimed to explore the subjective sense of well-being in a typical Iranian urban sample, focusing on the prevalent culture through a descriptive phenomenological inquiry. We derived themes and subthemes out of the individual expressions that helped identify the individuals’ experience of well-being while being reflective of the nation’s unique and complex culture. Our main intention was to contribute to the literature that analyzes the multi-cultural sense of well-being in their residents and to provide junior researchers, health practitioners, and lawmakers in Iran with insight toward the ultimate improvement of the status of well-being in research and policy-making.

Participants and Methods

The participants were 60 urban adults aged 18 to 65 years from Tehran, Iran. To recruit the participants, we used purposeful sampling [25] to ensure they came evenly from varying demographic strata with typical views on well-being.

Prior to initiating the study, we received the approval of the “Blinded for Review”. Also, the reviewed and signed written informed consents were received from the participants consistent with the University’s guidelines and based on the Helsinki Declaration before the data collection started. Participation was entirely voluntary for the subjects whose mother tong was Persian. They reviewed the study protocol and had the right to leave the study any time when they wished; however, they all stayed with the study through to its conclusion. We used a semi-structured interview system to explore the participants’ experiences and definition of subjective well-being. The interviews were administered in Persian by one individual throughout the study, and the term “subjective well-being” was used in Farsi words most commonly spoken in their daily conversation. At the beginning of the interviews, the aim of the study was explained again to the participants while they reviewed the study’s brief outline.

The interview began with a general question asked of each participant: “What is well-being for you?” or “How do you understand the word well-being”. In order to evoke profound responses, the interviewer went on with other probing questions, such as: “What changes in your life happen when you are in a state of well-being?” The interviews continued until the interviewee did not have any further responses to offer. Given the participants’ schedule for the day and their willingness, the interviews took 40 to 60 minutes to complete. All interviews were carefully recorded and later transcribed. Finally, each transcribed text was compared with the corresponding recorded audio file for consistency and accuracy.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using the descriptive phenomenological method of Colaizzi, including the following steps [27, 28]:

Step 1: The participants’ narratives, called “protocol”, were carefully reviewed several times by the first author.

Step 2: Upon reviewing the protocol, critical sentences were chosen that were directly reflective of the concept of subjective well-being. At the completion of this step, 700 closely related statements had been identified and extracted.

Step 3: To conduct a systematic interpretation of the selected statements, they were reviewed and discussed collectively by the authors to get the true connotations.

Step 4: The above steps were repeated for all 60 interview protocols. Then they were arranged in a separate folder under the respective themes together with their interpretations.

Step 5: The data collected in Step 4 were integrated into a series of comprehensive components of subjective well-being.

Step 6: To understand the intrinsic structure of subjective well-being, comprehensive descriptions of the components were compiled, consisting of the clear statements and the basic structure of the phenomenon.

Step 7: To write down the study findings, the polished narratives were assigned to the respective participants for a final review. After the necessary editing, the report was finalized and compiled.

Step 8: Seven themes emerged that were linked to the descriptions of the participants’ verbalized subjective well-being, which were categorized under such headings as comprehensiveness, overlaps, bias, and homogeneity.

Step 9: The themes’ validity was assessed based on the guidelines of the study protocol.

At this point, the main themes and the subthemes were discussed among the four authors and the consistency and appropriateness of the codes, and the titles for the themes and subthemes were finalized, after making minor adjustments as needed.

Findings

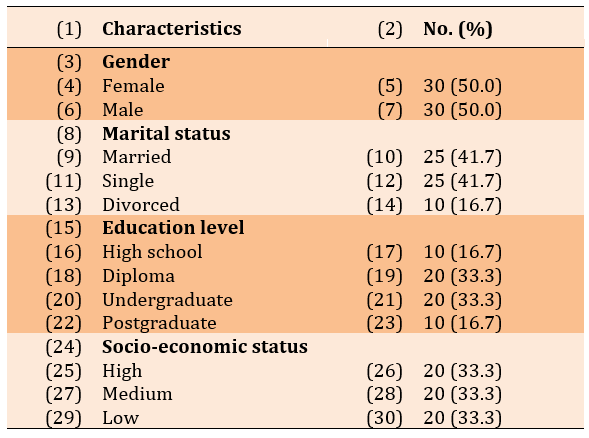

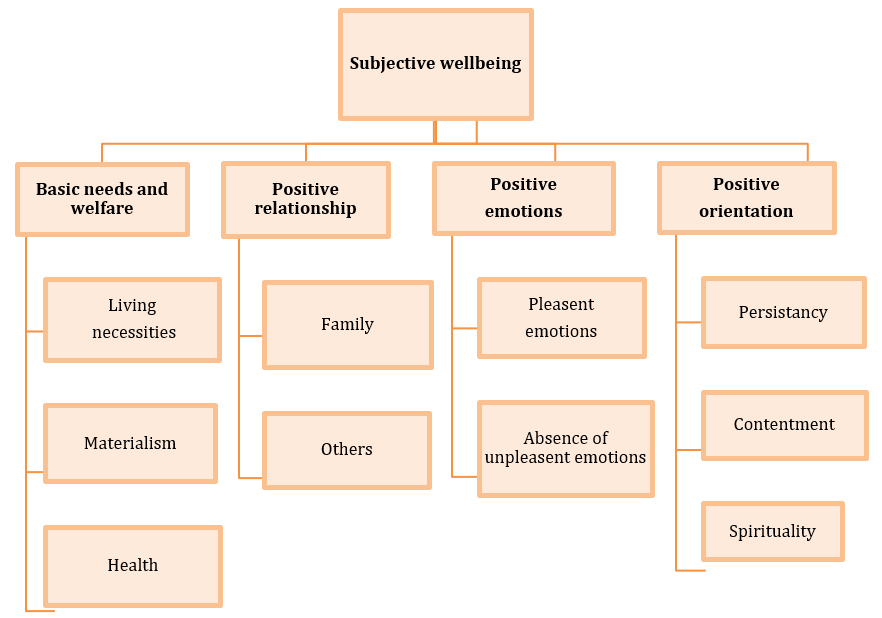

The mean age of the participants was 38.30 years in the range of 18-65 years. Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of the main demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1) Frequency distribution of participants' characteristics (n=60)

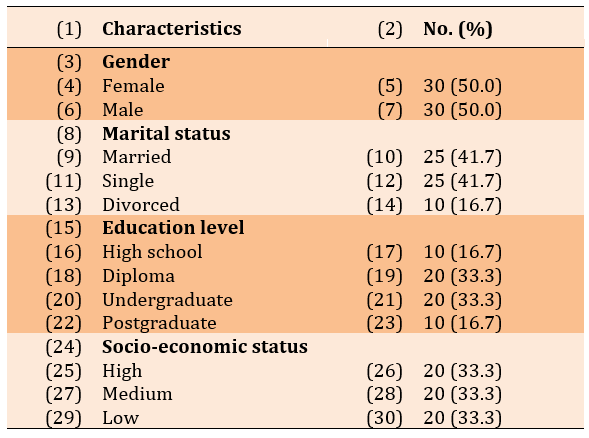

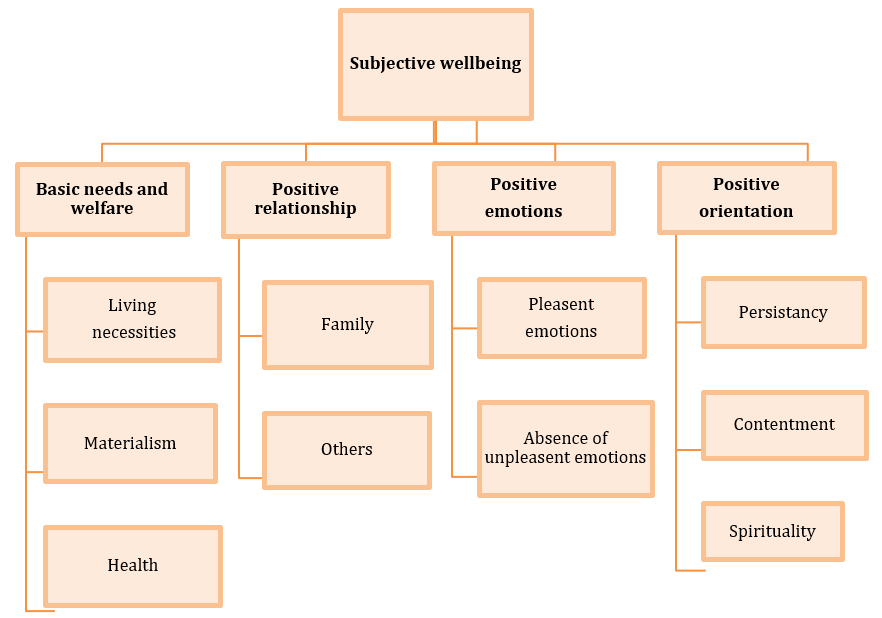

Four overarching themes immerged out of the final analyses, encompassing the ways the participants expressed subjective well-being in their daily lives. Figure 1 presents these four main themes and the subthemes that were identified and titled as: (a) Basic needs and welfare, (b) Positive relationships, (c) Positive emotions, and (d) Positive orientation. The participants stated their understanding of subjective well-being as a state of fulfillment and satisfaction under the four different themes. What follows are the descriptions of the themes and subthemes together with the typical participants’ expressions under each category:

Theme 1: Basic needs and welfare

This theme was about meeting the basic needs in the participants’ lives. Having the basic needs for self and the family met was essential to their experience of subjective well-being. The fulfillment of the basic needs and welfare was expressed under three interrelated and distinct subthemes.

• The first was having the bare minimum life necessities and facilities for living. These consisted of food, housing, and a few amenities that one needs. The next was materialism to purchase a big house and an expensive car, and the third was having their physical and mental health. Most participants of different ages and socioeconomic backgrounds stated that their subjective well-being began when the following basic needs were fulfilled:

Subjective well-being refers to an overall evaluation of the quality of a person’s life from her/his own view. It represents the extent to which a person believes that her/his life affairs are going well [1, 2]. The evaluation of subjective well-being involves both the cognitive and emotional components. The cognitive aspect refers to the person’s general assessment of life events, while the emotional one involves the presence of positive emotions and the absence of negative feelings. A survey on well-being has suggested that positive emotions and life satisfaction are the most significant components of subjective well-being [3]. The findings of this survey reveal that people differentiate between happiness as a temporary emotional state and life satisfaction, which is an overarching assessment of one’s life. Indeed, subjective well-being is a deeper concept than the individual experience of being in a temporary pleasant mood. Since there is a vast wealth of literature on various aspects of well-being, we first present a brief review of recent literature on the most relevant aspect of the subject, followed by introducing the specific aim of this study. In recent years, numerous studies have suggested a strong link between well-being and desirable consequences, such as health and longevity [4-6], good job, high income [7, 8], desirable social interactions, and few or no negative feelings [9-11]. In most cultures, subjective well-being has been emphasized at both individual and social levels [12, 13].

Although some studies have suggested numerous key factors contributing to subjective well-being, others believe that the components of well-being vary across various cultures. For instance, 13118 college students in 31 country completed measures of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and satisfaction with specific domains, such as friends, family, and significant others [14]. The results of this study suggested that self-esteem was the most significant indicator of well-being and life satisfaction in such nations as the United States and New Zealand compared to older cultures like Egypt and Japan. Meanwhile, emotional support and pleasant relationships with others are indicators of well-being and life satisfaction in Hong Kong [15] and Japan [16].

A study by Parnami et al. in 2013, which was conducted on a sample of 400 adults in an Indian population, demonstrated that religion and community support were important determinants of enhancing one's perception of well-being [17]. Later in 2016, Delle Fave et al. studied a sample of 2799 adults from 11 countries and explored their definition of happiness [18]. This study used open-ended questions and asked the participants: “What is happiness for you?”. The answers encompassed various definitions addressing a broad range of life domains, from contextual and social domains to psychological areas. The analysis of the responses revealed that despite minimal variations in age and gender among the participants, emotional satisfaction from within predominated the psychological definitions, with family and social relationships being the second main contextual definitions.

In another qualitative study using a thematic analysis approach, thirty Indonesian adults participated in semi-structured interviews with a focus on their experience of well-being. The results of that study indicated that the fulfillment of basic needs, social relations, and the positive world views of self-acceptance, gratitude, and spirituality were the main aspects of subjective well-being [19]. The common interpretation of the above studies is that social relationship with family and community, as well as spirituality, played strong roles in the experience of well-being in Eastern cultures.

Further research in Iranian society is necessary, complementing the scarce literature in this field to increase our understanding of subjective well-being among Eastern cultures. Such a study should address the gap between the experience of subjective well-being and the individual definition and expectation of well-being within an Iranian population. The findings might be different from those known for Western nations and even for some Eastern cultures. Several earlier studies conducted in Iran focused on correlational variables associated with subjective well-being [20-22].

Not many well-focused studies have been conducted on this critical subject so far in Iran to date to explore the subjective definition of well-being. Interestingly, based on the latest World Happiness Report (2017), Iran ranked 105 among the 157 countries, with a subjective well-being score of 4.8. In this context, Iran, as the sixth most populous Muslim country, is an example of an Eastern developing nation with its own cultural, social and religious perspectives. Therefore, exploring the critical components of subjective well-being in Iran is a major challenge both for the people and the government. This study is an attempt to explore this subject and to contribute to overall plans aimed at enhancing the spirit of subjective well-being within the Iranian society.

Due to the current limitations facing research on well-being in Iran, we planned to use social interpretive instead of a theoretical framework in designing the present study. This interpretive approach encourages researchers to have an insight into human behavior and its interaction with society. This involves developing an in-depth understanding of people’s thoughts and beliefs about themselves and society [23]. As have been recommended by many researchers, such an understanding will be further enhanced if in-depth research is undertaken on the personal interpretations of well-being [18]. Such an in-depth qualitative and contextual approach necessitates gaining a thorough understanding of well-being at individual level and across cultures and the society, shedding light on socio-economic and cultural [19, 23]. This approach will help shedding light on how subjective well-being is evaluated and whether the current definitions of subjective well-being are culturally acceptable.

Well-being studies have little to offer about subjective well-being in Iranian society, with cultural differences compared to both the Eastern and Western nations. It justifies undertaking a descriptive phenomenological study as the framework, such as the one employed in this study [24]. Phenomenology is defined the study of lived experiences with a focus on discovery. We chose this method since it is based on describing particular phenomena or emergence of events as the individual experiences them throughout life [25]. In this descriptive method, researchers make no interpretations; rather, they analyze the descriptions verbalized by participants and group them into meaningful statements. Collecting the meanings are essential to the foundation of the phenomenon under study [26].

This study aimed to explore the subjective sense of well-being in a typical Iranian urban sample, focusing on the prevalent culture through a descriptive phenomenological inquiry. We derived themes and subthemes out of the individual expressions that helped identify the individuals’ experience of well-being while being reflective of the nation’s unique and complex culture. Our main intention was to contribute to the literature that analyzes the multi-cultural sense of well-being in their residents and to provide junior researchers, health practitioners, and lawmakers in Iran with insight toward the ultimate improvement of the status of well-being in research and policy-making.

Participants and Methods

The participants were 60 urban adults aged 18 to 65 years from Tehran, Iran. To recruit the participants, we used purposeful sampling [25] to ensure they came evenly from varying demographic strata with typical views on well-being.

Prior to initiating the study, we received the approval of the “Blinded for Review”. Also, the reviewed and signed written informed consents were received from the participants consistent with the University’s guidelines and based on the Helsinki Declaration before the data collection started. Participation was entirely voluntary for the subjects whose mother tong was Persian. They reviewed the study protocol and had the right to leave the study any time when they wished; however, they all stayed with the study through to its conclusion. We used a semi-structured interview system to explore the participants’ experiences and definition of subjective well-being. The interviews were administered in Persian by one individual throughout the study, and the term “subjective well-being” was used in Farsi words most commonly spoken in their daily conversation. At the beginning of the interviews, the aim of the study was explained again to the participants while they reviewed the study’s brief outline.

The interview began with a general question asked of each participant: “What is well-being for you?” or “How do you understand the word well-being”. In order to evoke profound responses, the interviewer went on with other probing questions, such as: “What changes in your life happen when you are in a state of well-being?” The interviews continued until the interviewee did not have any further responses to offer. Given the participants’ schedule for the day and their willingness, the interviews took 40 to 60 minutes to complete. All interviews were carefully recorded and later transcribed. Finally, each transcribed text was compared with the corresponding recorded audio file for consistency and accuracy.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using the descriptive phenomenological method of Colaizzi, including the following steps [27, 28]:

Step 1: The participants’ narratives, called “protocol”, were carefully reviewed several times by the first author.

Step 2: Upon reviewing the protocol, critical sentences were chosen that were directly reflective of the concept of subjective well-being. At the completion of this step, 700 closely related statements had been identified and extracted.

Step 3: To conduct a systematic interpretation of the selected statements, they were reviewed and discussed collectively by the authors to get the true connotations.

Step 4: The above steps were repeated for all 60 interview protocols. Then they were arranged in a separate folder under the respective themes together with their interpretations.

Step 5: The data collected in Step 4 were integrated into a series of comprehensive components of subjective well-being.

Step 6: To understand the intrinsic structure of subjective well-being, comprehensive descriptions of the components were compiled, consisting of the clear statements and the basic structure of the phenomenon.

Step 7: To write down the study findings, the polished narratives were assigned to the respective participants for a final review. After the necessary editing, the report was finalized and compiled.

Step 8: Seven themes emerged that were linked to the descriptions of the participants’ verbalized subjective well-being, which were categorized under such headings as comprehensiveness, overlaps, bias, and homogeneity.

Step 9: The themes’ validity was assessed based on the guidelines of the study protocol.

At this point, the main themes and the subthemes were discussed among the four authors and the consistency and appropriateness of the codes, and the titles for the themes and subthemes were finalized, after making minor adjustments as needed.

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 38.30 years in the range of 18-65 years. Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of the main demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1) Frequency distribution of participants' characteristics (n=60)

Four overarching themes immerged out of the final analyses, encompassing the ways the participants expressed subjective well-being in their daily lives. Figure 1 presents these four main themes and the subthemes that were identified and titled as: (a) Basic needs and welfare, (b) Positive relationships, (c) Positive emotions, and (d) Positive orientation. The participants stated their understanding of subjective well-being as a state of fulfillment and satisfaction under the four different themes. What follows are the descriptions of the themes and subthemes together with the typical participants’ expressions under each category:

Theme 1: Basic needs and welfare

This theme was about meeting the basic needs in the participants’ lives. Having the basic needs for self and the family met was essential to their experience of subjective well-being. The fulfillment of the basic needs and welfare was expressed under three interrelated and distinct subthemes.

• The first was having the bare minimum life necessities and facilities for living. These consisted of food, housing, and a few amenities that one needs. The next was materialism to purchase a big house and an expensive car, and the third was having their physical and mental health. Most participants of different ages and socioeconomic backgrounds stated that their subjective well-being began when the following basic needs were fulfilled:

“I think well-being means not being poor…. It is when I have the bare necessities and facilities in life like food, clothes, and housing, and don’t need help from someone else… It is when I can buy things that I need” (Male, 36, low income).

“Well-being means my current situation; I have a good house, ample income, and have the necessary resources for living” (Female, 42, high income).

• The second subtheme was materialism. Under this subtheme, the participants cited having a big house, a modern car, access to recreational facilities, plus going on domestic and/or foreign trips. This finding may be particular to developing countries such as Iran, where having comfortable material needs is considered a luxury for much of the population. This is largely due to this country being under harsh international sanctions. A statement by one participant was expressed as follows:

“Well-being means my current situation; I have a good house, ample income, and have the necessary resources for living” (Female, 42, high income).

• The second subtheme was materialism. Under this subtheme, the participants cited having a big house, a modern car, access to recreational facilities, plus going on domestic and/or foreign trips. This finding may be particular to developing countries such as Iran, where having comfortable material needs is considered a luxury for much of the population. This is largely due to this country being under harsh international sanctions. A statement by one participant was expressed as follows:

“For me, well-being means getting rich. A rich person has high income and can buy a luxury house and a high model car” (Male, 36, medium income).

On the other hand, Iran has become a consumer society, and having ample financial resources has become a dream as well as a class for most Iranians over the past several decades. The following statement is a good example:

“Wellbeing is a 5-letter word: M.O.N.E.Y. It is when I have enough money to get everything I need in my life, and people will respect me for that status” (Male, 25, low income).

• The third subtheme was health, which was defined as being physically and mentally in good shape. All participants directly stated that subjective well-being depended upon physical and mental health for them and their families. The importance of health to subjective well-being is reflected in the following statements:“For me, the first sign of well-being is having a healthy body. If my body is not healthy, having other things will not help me” (Male, 35, medium income).

On the other hand, Iran has become a consumer society, and having ample financial resources has become a dream as well as a class for most Iranians over the past several decades. The following statement is a good example:

“Wellbeing is a 5-letter word: M.O.N.E.Y. It is when I have enough money to get everything I need in my life, and people will respect me for that status” (Male, 25, low income).

• The third subtheme was health, which was defined as being physically and mentally in good shape. All participants directly stated that subjective well-being depended upon physical and mental health for them and their families. The importance of health to subjective well-being is reflected in the following statements:“For me, the first sign of well-being is having a healthy body. If my body is not healthy, having other things will not help me” (Male, 35, medium income).

Another participant had this to say:

“Not being ill and having my physical and mental health means well-being to me” (Female, 50, high income).

Most of the participants were from a medium to high socioeconomic status and had reasonable financial resources. Nonetheless, their strong emphasis on finances and good health as the essential needs for their subjective well-being were indications to be strongly influenced by their cultural attitude. Lack of financial security and issues like peer comparisons,

Figure 1) Four main themes and subthemes

consumerism, and high greed for wealth and material gains were prevalent in the statements of most interviewees. The participants’ carefully worded comments on “luxury” showed their desire for materialistic and luxurious goods, which was linked to their sense of subjective well-being.

Theme 2: Positive relationships

The next main theme that emerged from our qualitative analysis was positive relationships with others. It was referred to a fundamental need for the participants’ sense of well-being. The importance of positive relationship, as expressed through their comments, was associated with having a good spouse and children and maintaining good relationships with them and others. They clearly identified this as one of the requirements for having a sense of subjective well-being. This theme is underscored by two different domains: (1) relationship with family members, including spouse, children, parents and relatives, and (2) relationship with others, such as friends, colleagues, etc.

• Although a typical Iranian family has extended relationships with significant others; however, in recent decades, family in Iran has been limited mostly to the immediate family members and parents. The linkage of the family to the individual’s sense of well-being was reflected in comments, such as follows:

“Not being ill and having my physical and mental health means well-being to me” (Female, 50, high income).

Most of the participants were from a medium to high socioeconomic status and had reasonable financial resources. Nonetheless, their strong emphasis on finances and good health as the essential needs for their subjective well-being were indications to be strongly influenced by their cultural attitude. Lack of financial security and issues like peer comparisons,

Figure 1) Four main themes and subthemes

consumerism, and high greed for wealth and material gains were prevalent in the statements of most interviewees. The participants’ carefully worded comments on “luxury” showed their desire for materialistic and luxurious goods, which was linked to their sense of subjective well-being.

Theme 2: Positive relationships

The next main theme that emerged from our qualitative analysis was positive relationships with others. It was referred to a fundamental need for the participants’ sense of well-being. The importance of positive relationship, as expressed through their comments, was associated with having a good spouse and children and maintaining good relationships with them and others. They clearly identified this as one of the requirements for having a sense of subjective well-being. This theme is underscored by two different domains: (1) relationship with family members, including spouse, children, parents and relatives, and (2) relationship with others, such as friends, colleagues, etc.

• Although a typical Iranian family has extended relationships with significant others; however, in recent decades, family in Iran has been limited mostly to the immediate family members and parents. The linkage of the family to the individual’s sense of well-being was reflected in comments, such as follows:

“Well-being for me means having a family, a good wife, and good children who are warm and intimate toward each other” (Male, 58, medium income).

“Well-being means I have a good husband, and I can maintain a good relationship with him and my children and other close relatives” (Female, 27, low income).

Participants also referred to the importance of family as a source of support that they would count on for emotional and financial support. For example:

“For me, having a warm and friendly family for support and help when I need them means my sense of well-being is met” (Female, 38, low income).

• Relationships with friends and significant others outside the family also emerged as the main aspect of the participants’ subjective well-being, some of which were associated with the relationship and support outside the family with their sense of well-being. For example:

“Well-being means I have a good husband, and I can maintain a good relationship with him and my children and other close relatives” (Female, 27, low income).

Participants also referred to the importance of family as a source of support that they would count on for emotional and financial support. For example:

“For me, having a warm and friendly family for support and help when I need them means my sense of well-being is met” (Female, 38, low income).

• Relationships with friends and significant others outside the family also emerged as the main aspect of the participants’ subjective well-being, some of which were associated with the relationship and support outside the family with their sense of well-being. For example:

“Wellbeing means having a good friend I can rely on" (Female, 42, low income).

“For me, well-being means having a good friend who will guide me and care for me throughout my life” (Male, 30, high income).

The reciprocal nature of a good relationship was also reflected in many participants’ statements as the important component of having a sense of well-being. What follows are two good examples:

“For me, well-being is helping others, helping those in need, especially in meeting their financial needs” (Female, 49, low income).

“Well-being for me is being able to do something useful for people. I need to think of helping others as much as I think of helping myself” (Male, 20, medium income).

The strong emphasis on the importance of family and having positive and strong relationships with others are consistent with the Iranian collectivist culture. This theme was stated not just as being supported by family and friends but also focused on helping family and others in the community. A positive relationship was expressed as good, intimate, and reciprocal interaction with family and others, which was strongly linked to the participant’s sense of well-being.

Theme 3: Positive emotions

The next main theme that emerged from the study results was positive emotions as an essential reason for the participants’ sense of well-being. Positive emotions were expressed through two interrelated but distinct subthemes.

• The first subtheme was being blessed with pleasant emotions, feeling of happiness, hope, pride and peace.

• The second subtheme was identified as the absence of unpleasant emotions, such as sadness “I think well-being means good feeling; when I feel happy and laugh” (Female, 42, medium income).

Low arousal positive affect also emerged as part of this subtheme from the participants’ comments. They referred to affect as inner peace and serenity regardless of the circumstances of life, as shown in the following example:

“Well-being means having inner peace with everything I have in life. How little and how much is not important. Well-being means total satisfaction” (Female, 30, high income).

Unpleasant emotions are typical to countries in the Middle East, such as Iran, where many people suffer from negative emotions for the right reasons, as exemplified by the following statements:

“I have a sense of well-being when I don’t feel sad or stressed out. Well-being means living without worries, I believe” (Male, 30, low income).

Another typical response was: “Well-being means someone who is not constantly anxious and worried so much like me. It is a person who sleeps peacefully at night and wakes up with full energy and hope in the morning” (Female, 51, high income).

Expressing the above comments indicated that having pleasant emotions and not having unpleasant feelings were the characteristic elements of the individual’s sense of well-being, regardless of their age and socio-economic status.

Theme 4: Positive orientation

A significant part of the comments made by the participants was about personal attitudes toward life and its linkage to their sense of well-being. Such attitudes were expressed about trying to achieve their goals in life, accepting what the individual cannot change with a sense of spirituality as the important components of subjective well-being. The attribute of trying to achieve one’s goals in life was labeled as persistence.

• As the first subtheme, persistency implied that participants tried hard to achieve their goals in their careers. Persistency was stated directly or indirectly by many participants as being the essential need for them to have a sense of well-being. The following statements reflect on this idea:

“For me, well-being means having a good friend who will guide me and care for me throughout my life” (Male, 30, high income).

The reciprocal nature of a good relationship was also reflected in many participants’ statements as the important component of having a sense of well-being. What follows are two good examples:

“For me, well-being is helping others, helping those in need, especially in meeting their financial needs” (Female, 49, low income).

“Well-being for me is being able to do something useful for people. I need to think of helping others as much as I think of helping myself” (Male, 20, medium income).

The strong emphasis on the importance of family and having positive and strong relationships with others are consistent with the Iranian collectivist culture. This theme was stated not just as being supported by family and friends but also focused on helping family and others in the community. A positive relationship was expressed as good, intimate, and reciprocal interaction with family and others, which was strongly linked to the participant’s sense of well-being.

Theme 3: Positive emotions

The next main theme that emerged from the study results was positive emotions as an essential reason for the participants’ sense of well-being. Positive emotions were expressed through two interrelated but distinct subthemes.

• The first subtheme was being blessed with pleasant emotions, feeling of happiness, hope, pride and peace.

• The second subtheme was identified as the absence of unpleasant emotions, such as sadness “I think well-being means good feeling; when I feel happy and laugh” (Female, 42, medium income).

Low arousal positive affect also emerged as part of this subtheme from the participants’ comments. They referred to affect as inner peace and serenity regardless of the circumstances of life, as shown in the following example:

“Well-being means having inner peace with everything I have in life. How little and how much is not important. Well-being means total satisfaction” (Female, 30, high income).

Unpleasant emotions are typical to countries in the Middle East, such as Iran, where many people suffer from negative emotions for the right reasons, as exemplified by the following statements:

“I have a sense of well-being when I don’t feel sad or stressed out. Well-being means living without worries, I believe” (Male, 30, low income).

Another typical response was: “Well-being means someone who is not constantly anxious and worried so much like me. It is a person who sleeps peacefully at night and wakes up with full energy and hope in the morning” (Female, 51, high income).

Expressing the above comments indicated that having pleasant emotions and not having unpleasant feelings were the characteristic elements of the individual’s sense of well-being, regardless of their age and socio-economic status.

Theme 4: Positive orientation

A significant part of the comments made by the participants was about personal attitudes toward life and its linkage to their sense of well-being. Such attitudes were expressed about trying to achieve their goals in life, accepting what the individual cannot change with a sense of spirituality as the important components of subjective well-being. The attribute of trying to achieve one’s goals in life was labeled as persistence.

• As the first subtheme, persistency implied that participants tried hard to achieve their goals in their careers. Persistency was stated directly or indirectly by many participants as being the essential need for them to have a sense of well-being. The following statements reflect on this idea:

“I think well-being is having a goal in life. I need to set a series of goals in different domains and move in that direction. Meanwhile, I shouldn’t hurt anyone in order to make my dreams come true” (Female, 30, high income).

“Simply put, well-being is the equivalent of success. Success means achieving the goals I have chosen for myself. For example, I am a student, and I have my educational and career goals. If I achieve them, it means I have achieved my sense of well-being” (Male, 22, medium income).

The notion of persistency was expressed by the participants across all ages, gender, and socio-economic strata and was reflected as the force behind achieving a positive and dynamic status in their lives.

• The second subtheme refers to contentment and the status quo, i.e., living with what we can or cannot change. It was termed contentment, implying that the participants accepted themselves and their life circumstances as they were. In other words, they accepted things as they were, whether they could change them or not regardless of making efforts. The Participants’ comments implied that contentment was one of the essential requirements before they could achieve a sense of well-being. The following typical examples represent that notion:

“Simply put, well-being is the equivalent of success. Success means achieving the goals I have chosen for myself. For example, I am a student, and I have my educational and career goals. If I achieve them, it means I have achieved my sense of well-being” (Male, 22, medium income).

The notion of persistency was expressed by the participants across all ages, gender, and socio-economic strata and was reflected as the force behind achieving a positive and dynamic status in their lives.

• The second subtheme refers to contentment and the status quo, i.e., living with what we can or cannot change. It was termed contentment, implying that the participants accepted themselves and their life circumstances as they were. In other words, they accepted things as they were, whether they could change them or not regardless of making efforts. The Participants’ comments implied that contentment was one of the essential requirements before they could achieve a sense of well-being. The following typical examples represent that notion:

“Well-being means, don’t be jealous and don’t compare my life with those of others” (Female, 30, low income).

“For me, well-being means accepting the situation as is and situations that I face. It is being happy and content with them” (Female, 58, high income).

Surprisingly, the concept of contentment was found more among females at different ages and socio-economic status than the males. It was especially emphasized by women who enjoyed a pleasant, uneventful, and peaceful life.

• The third subtheme under this category was “spirituality”. Some participants indicated that spirituality was a source of their sense of well-being. Participants remarked about spirituality as an orientation based on faith and believing in God as a supreme power and the importance of accepting his will in their lives. Spirituality was often expressed as an important coping mechanism when facing difficulties and hardship. What follows are the typical examples:

“For me, well-being means accepting the situation as is and situations that I face. It is being happy and content with them” (Female, 58, high income).

Surprisingly, the concept of contentment was found more among females at different ages and socio-economic status than the males. It was especially emphasized by women who enjoyed a pleasant, uneventful, and peaceful life.

• The third subtheme under this category was “spirituality”. Some participants indicated that spirituality was a source of their sense of well-being. Participants remarked about spirituality as an orientation based on faith and believing in God as a supreme power and the importance of accepting his will in their lives. Spirituality was often expressed as an important coping mechanism when facing difficulties and hardship. What follows are the typical examples:

"When I don’t have someone to talk to or I have something that I cannot share with anyone else, what I do is to pray to God. I just express what I have in my mind to God and ask for his guidance about what I wish to get” (Female, 25, medium income).

Spirituality was seen by some participants as a way to overcome unfavorable life circumstances, which helped them re-frame the undesirable issues and accept them. The following is a good example:

“If I believe in God, I know that everything that happens to me is his will, and it should be good, even if I do not know the reason” (Female, 34, low income).

Performing religious rituals and doing prayers were included often in the participants’ remarks, which was associated with bringing them a sense of well-being. The above three subthemes were referred to as the orientation in people linked to their subjective well-being. This orientation helped them endure tough life challenges while trying their best to achieve their goals and accepting life circumstances as they unfold. Also, reframing life realities from a spiritual point of view was mentioned as being helpful to attain a sense of well-being. In this context, this orientation helped the participants achieve a sense of fulfillment and contributed significantly to their subjective sense of well-being.

Discussion

This study explored the concept and connotation of subjective well-being in an Iranian urban sample. The findings provide a basis for the cultural understanding of subjective well-being for individuals from various socio-economic and cultural backgrounds [18]. The qualitative data analysis showed that the main components of subjective well-being for the participants were having their basic needs and welfare met in addition to having positive emotions, relationships, persistency, contentment and spirituality. While some of the themes are similar to other bases for the sense of well-being, the subthemes provided deeper insight into the Iranian cultural manner of expression about this sense. Our findings indicate that urban Iranians appear to view subjective well-being as a multi-dimensional construct consistent with the structures of well-being in other Eastern nations. The themes and subthemes may be examined and explored on theoretical bases, systematic research findings and cultural value systems.

Due to the limitations of research in the field of wellbeing in Iran, we intended to use social interpretivism as a conceptual framework instead of a specific theoretical framework in the present study. The interpretivism view invites the researcher to investigate meaning behind the understanding of human behavior, interactions and society. It involves the researcher's attempt to develop an in-depth subjective understanding of people’s lives [23]. The importance of such contextual analysis has recommended by several researchers to extend on the current wellbeing research [18]. Contextual exploration refers to the in-depth subjective understanding of wellbeing across cultures and society to explore differences due to variations in socio-economic and cultural circumstances [19]. Adopting an in-depth qualitative approach is supported in the literature as a suitable method for such contextual exploration [23]. This method may help to tell how subjective wellbeing is evaluated or whether the present definitions of subjective wellbeing are culturally appropriate.

Basic needs and welfare

For many of the participants, the fulfillment of basic needs as the main indicators of subjective well-being. Most participants stated that it was impossible or very difficult for them to have a sense of well-being without satisfying the stated needs. The findings are consistent with those of previous studies that suggested subjective well-being and its tangible determinants, such as income, as the most important indicators of subjective well-being in most nations [29-31]. The impact of the fulfilled basic needs and welfare on the subjective well-being is not questionable since financial affordability impacts many aspects of an individual’s life. Also, the association of health with subjective well-being is consistent with the findings of another study [21], which suggested that health has a considerable effect on the individual’s sense of well-being in Iran. Having good income provides for access to good healthcare facilities and enables people to have a greater sense of well-being [2].

Positive relationships

The importance of having positive relationships with family and others as a major component of subjective well-being was highlighted by all of the participants. Positive relationships were expressed as the practical means of helping others, which was as important as receiving support and friendship from them. The majority of the participants declared that happiness in their family was as important as their own happiness and sense of well-being. These findings are consistent with those reported by past studies [19, 32-35] as they all considered family and social relations as the major components of one’s sense of well-being in non-Western countries. Delle et al. demonstrated that almost half of the responses received in a qualitative research were associated with relationships, where 29% of the codes were related to family and 27% linked to interpersonal relationships [18].

According to recent findings in neuroscience based on cultural relations theory [36], relationships have a major share in the individual’s psychological development. This theory highlights the key role of original, reciprocal relationships as the foundation for the individual’s sense of well-being. It holds that psychological development leads to positive relationships, and isolation causes emotional distress. In this context, Asian people place high value on relationships with family and community, which stem from their collectivist culture. It places reciprocal helping of members of the society as an important personal goal or almost a moral duty [37]. Although the importance of positive relationships in subjective well-being has been explored by various studies in Western and Eastern cultures, the components of this theme, as identified in the current study, were somewhat different from those of most Western and even some Eastern nations. Western studies are profoundly strong in social relationships [38]. However, the current study highlighted the importance of family relationships and its contribution to the individual’s sense of well-being. In Eastern cultures, the focus is more on the main family than the extended one, and often people prefer to attend to their own family’s social, emotional and financial needs. Unlike the East Asian cultures, our participants associated their personal happiness with helping their communities.

Positive emotions

The importance of positive emotions, such as inner peace, was clearly expressed by most participants. This concept is consistent with that reported by previous studies, underscoring the contribution of positive emotions to the individual’s sense of well-being [39-42]. The findings of our study suggest that both positive and negative emotions impacted the participants’ subjective well-being. Lack of stress, anxiety, and sadness were evident in the majority of the interviews. Since many people suffer from negative emotions in Iran [43], the absence of this feeling implied the participants’ normal sense of well-being. Studies have shown that negative emotions have a significant adverse effect on the sense of well-being among Eastern Asians and Asian Americans. Conversely, Europeans and European Americans enjoy significant amounts of positive emotions [44, 45]. Therefore, our findings indicate that both positive and negative emotions are the important components of the people’s sense of well-being.

Positive orientations

Positive orientation, as expressed by the participants, was a major factor for their sense of well-being. The components of positive orientation were persistency, contentment and spirituality. The role of persistency in attaining the participants’ personal goals is consistent with findings from an earlier study by Noferesti et al. in 2016 [46]. That study suggested that having personal well-defined goals and pursuing them were strongly associated with the sense of well-being. Also, Balas and Dorling have stated that major events, such as graduating from university and getting career promotion are among the positive factors for the individual’s sense of well-being [47]. Our participants pointed out that having goals and achieving them in different domains, such as education and career, gave them a clear direction in their lives and led them to success. Although Iran is an Asian nation with a predominantly collectivist culture, people emphasize personal achievements. This finding is inconsistent with those reported by other studies, suggesting that people in collectivist cultures are highly interested in having social goals [44]. Further research is warranted to examine the linkage between achieving personal goals and having a sense of well-being across other Iranian communities.

The participants also considered the share of contentment as one of the factors for their subjective well-being. In our study, it was noted that the concept of contentment was highlighted more often by women than men. Contentment has not been studied widely especially for its role in the individual’s sense of well-being in Iran. Our findings open up a new horizon on the value of contentment as a significant part of the individuals’ sense of subjective well-being, worthy of research in various cultures. Further research on this subject and its role in person’s subjective well-being in various Eastern cultures is warranted.

Spirituality immerged as another important factor contributing to the sense of well-being in the participants, which was consistent with previous studies conducted in Iran [20, 46]. It is no surprise since Iran is a religious society, and people usually apply religious principles, rituals and values to their life challenges. Researchers have reported that religious beliefs could have a considerable role as a protective factor to help people cope with unfavorable life circumstances by believing that God provides them with ways to deal with misfortunes that may happen to them [48, 49]. Spirituality can empower people in religious communities to attain a sense of serenity even in difficult times and leads them to a sense of well-being [5].

Finally, the present study discovered a cultural context for subjective well-being in a sample of urban Iranian participants that may represent a similar context for this nation at large. While the main themes are consistent with a universal definition of subjective well-being, the subthemes were somewhat different. Iran is a nation of diverse communities and the sixth most populous Muslim country in the world with unique cultural and spiritual values that are likely to be different from those in the West and even Eastern cultures. This study supports the important association between cultural and spiritual contexts and the perception of well-being. This qualitative study was the first to explore the perception of subjective well-being in a homogeneous population of urban Iranian adults.

Limitation of the study: The results do not represent the diverse Iranian cultural and social strata. Iran is a country with diverse traditions, customs, cultures, and religious beliefs that could impact the components of subjective wellbeing in different provinces. Moreover, the ages of participants of the study ranged between 18 and 65, thus, the results of the study cannot be applied to people under 18 and above 65.

Recommendations for future research: Other studies could be conducted to determine the components of well-being and happiness in elderly populations of Iran. Also, further research is recommended, using different methodological approaches, and participants will enhance our understanding of this construct. Lastly, further research is needed to examine the linkage between achieving personal goals and improving the sense of well-being across other Iranian communities.

Conclusion

The themes and subthemes associated with the participants' senses of well-being are as follows: fulfillment of basic needs and welfare, positive relationship with family and community, having positive emotion, and orientation toward persistency, contentment, and spirituality.

Although some of these concepts have commonly been reported in well-being literature, they are unique in the Iranian cultural context. The study findings enhance the current subjective well-being literature and understanding of the experience in the Iranian culture and contribute to the limited knowledge about well-being in Iran.

Acknowledgements: We thank the Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR) for providing research facilities to the researchers.

Ethical Permission: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ACECR research committee.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Noferesti A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (60%); Behfar Z (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Salehi K (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding: This study was funded by the Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR).

Spirituality was seen by some participants as a way to overcome unfavorable life circumstances, which helped them re-frame the undesirable issues and accept them. The following is a good example:

“If I believe in God, I know that everything that happens to me is his will, and it should be good, even if I do not know the reason” (Female, 34, low income).

Performing religious rituals and doing prayers were included often in the participants’ remarks, which was associated with bringing them a sense of well-being. The above three subthemes were referred to as the orientation in people linked to their subjective well-being. This orientation helped them endure tough life challenges while trying their best to achieve their goals and accepting life circumstances as they unfold. Also, reframing life realities from a spiritual point of view was mentioned as being helpful to attain a sense of well-being. In this context, this orientation helped the participants achieve a sense of fulfillment and contributed significantly to their subjective sense of well-being.

Discussion

This study explored the concept and connotation of subjective well-being in an Iranian urban sample. The findings provide a basis for the cultural understanding of subjective well-being for individuals from various socio-economic and cultural backgrounds [18]. The qualitative data analysis showed that the main components of subjective well-being for the participants were having their basic needs and welfare met in addition to having positive emotions, relationships, persistency, contentment and spirituality. While some of the themes are similar to other bases for the sense of well-being, the subthemes provided deeper insight into the Iranian cultural manner of expression about this sense. Our findings indicate that urban Iranians appear to view subjective well-being as a multi-dimensional construct consistent with the structures of well-being in other Eastern nations. The themes and subthemes may be examined and explored on theoretical bases, systematic research findings and cultural value systems.

Due to the limitations of research in the field of wellbeing in Iran, we intended to use social interpretivism as a conceptual framework instead of a specific theoretical framework in the present study. The interpretivism view invites the researcher to investigate meaning behind the understanding of human behavior, interactions and society. It involves the researcher's attempt to develop an in-depth subjective understanding of people’s lives [23]. The importance of such contextual analysis has recommended by several researchers to extend on the current wellbeing research [18]. Contextual exploration refers to the in-depth subjective understanding of wellbeing across cultures and society to explore differences due to variations in socio-economic and cultural circumstances [19]. Adopting an in-depth qualitative approach is supported in the literature as a suitable method for such contextual exploration [23]. This method may help to tell how subjective wellbeing is evaluated or whether the present definitions of subjective wellbeing are culturally appropriate.

Basic needs and welfare

For many of the participants, the fulfillment of basic needs as the main indicators of subjective well-being. Most participants stated that it was impossible or very difficult for them to have a sense of well-being without satisfying the stated needs. The findings are consistent with those of previous studies that suggested subjective well-being and its tangible determinants, such as income, as the most important indicators of subjective well-being in most nations [29-31]. The impact of the fulfilled basic needs and welfare on the subjective well-being is not questionable since financial affordability impacts many aspects of an individual’s life. Also, the association of health with subjective well-being is consistent with the findings of another study [21], which suggested that health has a considerable effect on the individual’s sense of well-being in Iran. Having good income provides for access to good healthcare facilities and enables people to have a greater sense of well-being [2].

Positive relationships

The importance of having positive relationships with family and others as a major component of subjective well-being was highlighted by all of the participants. Positive relationships were expressed as the practical means of helping others, which was as important as receiving support and friendship from them. The majority of the participants declared that happiness in their family was as important as their own happiness and sense of well-being. These findings are consistent with those reported by past studies [19, 32-35] as they all considered family and social relations as the major components of one’s sense of well-being in non-Western countries. Delle et al. demonstrated that almost half of the responses received in a qualitative research were associated with relationships, where 29% of the codes were related to family and 27% linked to interpersonal relationships [18].

According to recent findings in neuroscience based on cultural relations theory [36], relationships have a major share in the individual’s psychological development. This theory highlights the key role of original, reciprocal relationships as the foundation for the individual’s sense of well-being. It holds that psychological development leads to positive relationships, and isolation causes emotional distress. In this context, Asian people place high value on relationships with family and community, which stem from their collectivist culture. It places reciprocal helping of members of the society as an important personal goal or almost a moral duty [37]. Although the importance of positive relationships in subjective well-being has been explored by various studies in Western and Eastern cultures, the components of this theme, as identified in the current study, were somewhat different from those of most Western and even some Eastern nations. Western studies are profoundly strong in social relationships [38]. However, the current study highlighted the importance of family relationships and its contribution to the individual’s sense of well-being. In Eastern cultures, the focus is more on the main family than the extended one, and often people prefer to attend to their own family’s social, emotional and financial needs. Unlike the East Asian cultures, our participants associated their personal happiness with helping their communities.

Positive emotions

The importance of positive emotions, such as inner peace, was clearly expressed by most participants. This concept is consistent with that reported by previous studies, underscoring the contribution of positive emotions to the individual’s sense of well-being [39-42]. The findings of our study suggest that both positive and negative emotions impacted the participants’ subjective well-being. Lack of stress, anxiety, and sadness were evident in the majority of the interviews. Since many people suffer from negative emotions in Iran [43], the absence of this feeling implied the participants’ normal sense of well-being. Studies have shown that negative emotions have a significant adverse effect on the sense of well-being among Eastern Asians and Asian Americans. Conversely, Europeans and European Americans enjoy significant amounts of positive emotions [44, 45]. Therefore, our findings indicate that both positive and negative emotions are the important components of the people’s sense of well-being.

Positive orientations

Positive orientation, as expressed by the participants, was a major factor for their sense of well-being. The components of positive orientation were persistency, contentment and spirituality. The role of persistency in attaining the participants’ personal goals is consistent with findings from an earlier study by Noferesti et al. in 2016 [46]. That study suggested that having personal well-defined goals and pursuing them were strongly associated with the sense of well-being. Also, Balas and Dorling have stated that major events, such as graduating from university and getting career promotion are among the positive factors for the individual’s sense of well-being [47]. Our participants pointed out that having goals and achieving them in different domains, such as education and career, gave them a clear direction in their lives and led them to success. Although Iran is an Asian nation with a predominantly collectivist culture, people emphasize personal achievements. This finding is inconsistent with those reported by other studies, suggesting that people in collectivist cultures are highly interested in having social goals [44]. Further research is warranted to examine the linkage between achieving personal goals and having a sense of well-being across other Iranian communities.

The participants also considered the share of contentment as one of the factors for their subjective well-being. In our study, it was noted that the concept of contentment was highlighted more often by women than men. Contentment has not been studied widely especially for its role in the individual’s sense of well-being in Iran. Our findings open up a new horizon on the value of contentment as a significant part of the individuals’ sense of subjective well-being, worthy of research in various cultures. Further research on this subject and its role in person’s subjective well-being in various Eastern cultures is warranted.

Spirituality immerged as another important factor contributing to the sense of well-being in the participants, which was consistent with previous studies conducted in Iran [20, 46]. It is no surprise since Iran is a religious society, and people usually apply religious principles, rituals and values to their life challenges. Researchers have reported that religious beliefs could have a considerable role as a protective factor to help people cope with unfavorable life circumstances by believing that God provides them with ways to deal with misfortunes that may happen to them [48, 49]. Spirituality can empower people in religious communities to attain a sense of serenity even in difficult times and leads them to a sense of well-being [5].

Finally, the present study discovered a cultural context for subjective well-being in a sample of urban Iranian participants that may represent a similar context for this nation at large. While the main themes are consistent with a universal definition of subjective well-being, the subthemes were somewhat different. Iran is a nation of diverse communities and the sixth most populous Muslim country in the world with unique cultural and spiritual values that are likely to be different from those in the West and even Eastern cultures. This study supports the important association between cultural and spiritual contexts and the perception of well-being. This qualitative study was the first to explore the perception of subjective well-being in a homogeneous population of urban Iranian adults.

Limitation of the study: The results do not represent the diverse Iranian cultural and social strata. Iran is a country with diverse traditions, customs, cultures, and religious beliefs that could impact the components of subjective wellbeing in different provinces. Moreover, the ages of participants of the study ranged between 18 and 65, thus, the results of the study cannot be applied to people under 18 and above 65.

Recommendations for future research: Other studies could be conducted to determine the components of well-being and happiness in elderly populations of Iran. Also, further research is recommended, using different methodological approaches, and participants will enhance our understanding of this construct. Lastly, further research is needed to examine the linkage between achieving personal goals and improving the sense of well-being across other Iranian communities.

Conclusion

The themes and subthemes associated with the participants' senses of well-being are as follows: fulfillment of basic needs and welfare, positive relationship with family and community, having positive emotion, and orientation toward persistency, contentment, and spirituality.

Although some of these concepts have commonly been reported in well-being literature, they are unique in the Iranian cultural context. The study findings enhance the current subjective well-being literature and understanding of the experience in the Iranian culture and contribute to the limited knowledge about well-being in Iran.

Acknowledgements: We thank the Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR) for providing research facilities to the researchers.

Ethical Permission: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ACECR research committee.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Noferesti A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (60%); Behfar Z (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Salehi K (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding: This study was funded by the Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR).

Keywords:

References

1. Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi DW, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y]

2. Diener E, Lucas RE, Oishi S, Hall N, Donnellan MB. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 2018;4(1):15. [Link] [DOI:10.1525/collabra.115]

3. Helliwell JF, Huang H, Wang S. The distribution of world happiness [Internet]. New York: World Happiness; 2016 [cited 2017 May 12]. Available from: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2016/. [Link]

4. Steptoe A, Wardle J. Positive affect measured using ecological momentary assessment and survival in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(45):18244-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1110892108]

5. Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: Subjective well‐being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol Health Well‐Being. 2011;3(1):1-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x]

6. Gana K, Broc G, Saada Y, Amieva H, Quintard B. Subjective wellbeing and longevity: Findings from a 22-year cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2016;85:28-34. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.004]

7. De Neve JE, Oswald AJ. Estimating the influence of life satisfaction and positive affect on later income using sibling fixed effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(49):19953-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1211437109]

8. Walsh LC, Boehm JK, Lyubomirsky S. Does happiness promote career success? Revisiting the evidence. J Career Assess. 2018;26(2):199-219. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1069072717751441]

9. Quoidbach J, Taquet M, Desseilles M, de Montjoye YA, Gross JJ. Happiness and social behavior. Psychol Sci. 2019;30(8):1111-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0956797619849666]

10. Tay L, Diener E. Needs and subjective well-being around the world. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(2):354-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0023779]

11. Bos EH, Snippe E, de Jonge P, Jeronimus BF. Preserving subjective wellbeing in the face of psychopathology: buffering effects of personal strengths and resources. PloS One. 2016;11(3):e0150867. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0150867]

12. Diener E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):34-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34]

13. Ngamaba KH. Determinants of subjective well-being in representative samples of nations. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(2):377-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckx081]

14. Diener E, Diener C. The wealth of nations revisited: Income and quality of life. Soc Indic Res. 1995;36(3):275-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/BF01078817]

15. Kwan VS, Bond MH, Singelis TM. Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(5):1038-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1038]

16. Uchida Y, Kitayama S, Mesquita B, Reyes JA, Morling B. Is perceived emotional support beneficial? Well-being and health in independent and interdependent cultures. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2008;34(6):741-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0146167208315157]

17. Parnami M, Mittal U, Hingar A. Impact of religiosity on subjective well-being in various groups: A comparative study. Ind J Health Wellbeing. 2013;4(4):903-8. [Link]

18. Delle Fave A, Brdar I, Wissing MP, Araujo U, Castro Solano A, Freire T, et al. Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Front Psychol. 2016;7:30. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00030]

19. Maulana H, Obst T, Khawaja N. Indonesian perspective of wellbeing: A qualitative study. Qual Rep. 2018;23(12):3136-52. [Link] [DOI:10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3508]

20. Alavi HR. Correlatives of happiness in the university students of Iran (a religious approach). J Religion Health. 2007;46(4):480-99. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10943-007-9115-4]