Volume 14, Issue 1 (2022)

Iran J War Public Health 2022, 14(1): 111-118 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2022/03/11 | Accepted: 2022/04/12 | Published: 2022/04/9

Received: 2022/03/11 | Accepted: 2022/04/12 | Published: 2022/04/9

How to cite this article

Nassar S, Al-Idreesi S, Azzal G. Immune Responses in Patient Infected with Entamoeba histolytica and the Antigensity of Cyst in Basrah Province, Iraq. Iran J War Public Health 2022; 14 (1) :111-118

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1128-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1128-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Basrah University, Basrah, Iraq

Full-Text (HTML) (391 Views)

Introduction

Humans and animals in standing main worry about infection protozoan parasites to their strength cause enormous mortality and morbidity [1, 2]. Excess of five hundred million people across the world are accountable for affecting by these protozoa [3].

Humans in addition to primates ordinarily pollute of the large intestine with E. histolytica [4]. The occurrence was much shared in adults as comfortably as children, while it was quite extended in the tropical and subtropical areas [5]. It is considered as one of the most common parasitic infections worldwide with around 500 million infections per year and a leading cause of parasite related mortality with over 100,000 deaths annually. It has been shown that about 450 million persons were completely a contagion yearly, with about 50 million deaths [6].

Entamoeba histolytica has a two-stage life cycle, existing as resistant infective cysts in the environment and potentially pathogenic trophozoites in the human colon. Infection with E. histolytica results in invasion of the intestine by the parasite, followed by tissue damage and inflammation. During this invasive process, parasites kill and phagocytose human epithelial cells, immune cells and erythrocytes. The more common path is commensal colonization, where trophozoites inhabit the gut lumen and feed on enteric bacteria by phagocytosis [7, 8].

IL-8 was secreted as potent chemokines from intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) visible to E. histolytica trophozoites, causing immune cell employment and infiltration of the intestinal epithelium and basement membrane [9]. One of the first immune cells to respond to amebic attacks were neutrophils. This is triggered via interferon-γ (IFN-γ), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), they liberate reactive oxygen species (ROS) which carry out an amebicidal activity in vitro [10, 11].

Although in the intestinal tract the mucosal layer commonly works as a prime physical barrier in contradiction to pathogens of the intestine, the immune response to the intestinal is the secondary protection against E. histolytica infestation. Immunoglobulins of mucosal (Among them, secretory IgA) were the main factor in the human intestinal protection mechanism [12].

In contrast to E. histolytica, cell-mediated immune responses are also important for host defense. In the early stages of infection, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) connect to and diagnose the carbohydrate recognition domain of the Gal/GalNAc lectin via toll-like receptor (TLR)-2/4, which activates NFκB and results in the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IFN-, and TNF-α [13, 14]. IFN- has been linked to the clearance of infection, whereas IL-4 and TNF- have been linked to illness [15, 16].

Studying the immune response to E. histolytica is very important to investigate the early diagnosis of this disease. Hence, this study aimed to culture E. histolytica in vitro from the stool samples of humans, and the stage of the cyst was purified.

Materials and Methods

A total of 818 human stool samples and 300 blood samples (The Sera were kept at-20°C until further use) were collected from a patient with diarrhea attended in ALfayhaa, Albasrah, Aljmhoree, Al-sader teaching hospitals, and private clinics in Basrah city from September 2017- August 2018.

Stool examination

The macroscopic examination will be done according to AL-Shaheen et al. [17].

Parasite propagation

-Culture method: All stipulation of culture was worked beneath the sterilization in laminar flow to prepare LES (Lock-egg slant medium) (NIH Modification of Boeock and Drboh lava’s mediums) [18] The stool samples were collected from patients with amoebic dysentery. The samples (6-8) were collected and preserved at room temperature until use around 48h the samples were passed through the following steps: Elimination; Examination; Establishment of Culture; Incubation; Examination of Culture media and Isolations. The culture if positive for amoeba and the pellet between the recipient tubes was split. This can be accomplished by chilling the culture tubes in an ice water bath for 5 minutes, overturning the culture tubes several times to detach adhering amoebae, and transferring the fluid phase to an empty culture tube containing 13mL of medium. In addition, incubation as the procedure above.

-Purification Cyst of E. histolytica: The cysts were purified by using two methods, the first method was through a culture medium (LES) of E. histolytica: After planting the E. histolytica in the LES took the liquid containing the cyst, and transferred to another sterile tube. Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) 2ml was added after the verification of purity and examination through the microscope and kept (-20) until use. The second method was done by the precoll gradient. From stool samples(human) cysts were purified as defined previously with some changes [19, 20] Most 4-5 g of pass try was dissolved in PBS, filtered through two layers of gauges, centrifuged at 3220g for 20 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded in the instrument. The pellet was suspended in 5mL of ethyl acetate (to separate the cyst from the fecal debris) and centrifuged at 3220g for 20 minutes after (working three times). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was cleaned three more times with PBS (at 3220g for 20 repetitions) before being suspended in 2mL of PBS. This was then carefully layered in 176×120mm, 15mL high-clarity polypropylene conical tubes using a chemist pipette on top of a previously braced 10-80% Percoll position by layering 2mLs each of 80% Percoll (in PBS), followed by 50%, 40%, 30%, 20%, and 10% Percoll solutions. This was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 32206g. The accumulation of the Percoll gradient between 40-80% was transferred to a fresh tube, cleaned three times with PBS, and microscopically examined for pure cysts.

Preparation of E. histolytica proteins

The cysts were purified by the two methods above, the cyst protein of E. histolytica was prepared in the following steps 2mL of PBS (pH: 7.2) was added to the vial containing (Purified cysts of E. histolytica) and glass beads, and the vortex was done for (10min). Each 2mL of suspension received 200 microliters of lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P40, 10Mm Tris-HCL, Aprotinen 0.1U/ml, 1% Triton X -100) for around 24 hours. after that, the suspension was taken and sonication for (15min) intervals (30secound) the speed was 20Khz by sonicate apparatus. Centrifugation was done to the suspension by cold centrifuge for (30 min) the speed was (10000 rpm). The supernatant was taken as the source of protein. Nanodrop apparatus was used to measure the concentration of proteins.

Antigens description

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis recognizes E.histolytica antigens (SDS-PAGE). Boiling in decreasing loading buffer (LB; 25% glycerol, 5% beta-Mercaptoethanol, 10% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), 0.01% Bromophenol Amytal in Tris/ HCl (PH=6.8) 16Mm) lyzed E. histolytica cysts protein (50 μg) per lane. Then, using a 6-10 slope gel, a detachment was performed using (SDS-PAGE). The polypeptide was electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (BA85; 0.4M; Scheleiche and Schull, Inc.). Trans blot transfer cell by the semi-liquid western blot apparatus, the nitrocellulose membrane was swayed for 15min, with transfer buffer and then was used in the suitable place in western blot apparatus. The nitrocellulose sheet containing the polypeptide was washed two times, for 5 minutes each time, with distilled water after being exposed to an electric current of 250 mA for two hours and a half at a temperature of 4 C. Washing the nitrocellulose sheet with Tris buffer saline-tween (TBS-T) PH=7.5 (10mM Tris-HCl, 154mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween -20) plus to 3% bovine serum albumin for 24 hours at 4°C blocked spare tight spots. On a rotator shaker, the nitrocellulose sheet was advanced clean three times, for five minutes each time.

The sheet was then cut into strips that were detached into an individual container and exposed to primary antibodies (Nine sera samples were prepared from a patient with diarrhea) to the E. histolytica for one hour. Following washing, the nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen, California, USA) directed against E. histolytica antibodies, rinsed (3x5 minutes) in TBS-T buffer, and then brooded in OPD (Ortho Phenyl domain) substrate solution for 15-20 minutes with rotating till the band appeared. The nitrocellulose strips were washed twice with distilled water to halt the reactivity.

Evaluation of interferon- γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) induced in a patient infected with E. histolytica

According to the industrialist directive, human serum samples were tested for IL-4 and IFN- using ELISA kits (Elabscience Inc.). Study groups related between patients and control, patients infection and acute infection, patients male and female, and related age of patients were studied. Using an ELISA plate reader, the optical densities of kit standards and test samples were measured at (450nm) (HumaReader HS, Human, Germany). Pictograms of IL-4 and IFN- per mL of material were used to explain the results.

Macroscopic examination and epidemiological study were done by Nassar et al. [21].

Findings

Culture medium was registered elevation and success in the isolating of E.histolytica from the stool specimen. Because of the growth and activity of Amoeba after 48 hours incubation of the first isolation after culture medium. The culture medium was obtained more than 3-6 times with better growth of standard Amoeba for the culture medium Table 1.

Table 1) Number of cyst and trophozoite (culture and subculture media) below laboratory situation

The pure cysts of E. histolytica were obtained by precoll gradient; the content isolated amid 80% and 40% of the percoll gradient. The numbers of the purified cysts of E. histolytica by culture media were more than the numbers of the cysts purified by gradients percoll but the purity of the cysts were better than from the culture medium Table 2.

Table 2) Number of the cysts of E.histolytica(by use culture medium or precoll gradient)

Antigens analysis

SDS-PAGE was used to separate cyst proteins, which yielded polypeptides for the assay. Coomassie blue was used to stain eleven polypeptides in particular. 101, 95, 80, 69, 64, 57, 51.2, 49, 36.1, 26.1, and 22.1kDa were their molecular weights (Figure 1a).

Western blot with molecular weight 83, 69, 61, 34, 29.1, 18.1, and 11.2kDa was identified with immune serum post-infection the protective immune responses, by E. histolytica parasite (Figure 1b). After electrophoretic disconnection of cysts proteins, the Immunoblot of proteins transmits from a 6-10% SDS-PAGE. Lane was immunoblotting of cysts extracts preparations probed with immune serum.

Figure 1) a:Proteins (SDS-PAGE); b: Antigens (western blot)

ELISA assay

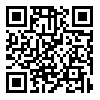

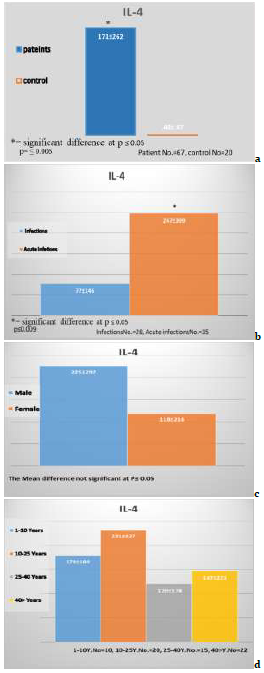

Recorded data displayed significant differences at amidst study groups related between patients and control, and the recent results referred to the concentrations IL-4, IL-4 exhibited a significant increase in the concentration of amebic patients (171.0±262.0pg/ml) in comparison to control (48.0±47.0pg/ml) as in Figure 2a (p<0.05).

Figure 2) The concentrations of IL-4

Recorded data observed significant differences at p≤0.05 among the study groups related through patients infection and acute infection, the recent result the IL-4 exhibited a significant decrease (p≤0.05) in the concentration of amebic patients infection (77.0±146.0pg/ml) in comparison to patient acute (247.0±309.0pg/ml) concentrations of IL-4 in regarding as in Figure 2b.

There were no significant differences (p>0.05) between research groups based on the data collected related through male and females patients the recent result referred to the concentrations of IL-4, As shown in Figure 2c, the concentration of IL-4 in male patients (225±292pg/ml) was not significantly different (p>0.05) from patient female (118±216pg/ml).

Recorded data showed no significant differences between study groups related to the age of patients the recent result referred to the concentrations of IL-4, IL-4 exhibited no significant differences in the concentration of patients age 1-10 years (178.0±189.0pg/ml) in comparison to 10-25 years (231.0±327.0pg/ml), 25-40 years (120.0±178.0ng/ml), and 40> years (147±221pgml) as in Figure 2d.

IFN-Ɣ

Humans and animals in standing main worry about infection protozoan parasites to their strength cause enormous mortality and morbidity [1, 2]. Excess of five hundred million people across the world are accountable for affecting by these protozoa [3].

Humans in addition to primates ordinarily pollute of the large intestine with E. histolytica [4]. The occurrence was much shared in adults as comfortably as children, while it was quite extended in the tropical and subtropical areas [5]. It is considered as one of the most common parasitic infections worldwide with around 500 million infections per year and a leading cause of parasite related mortality with over 100,000 deaths annually. It has been shown that about 450 million persons were completely a contagion yearly, with about 50 million deaths [6].

Entamoeba histolytica has a two-stage life cycle, existing as resistant infective cysts in the environment and potentially pathogenic trophozoites in the human colon. Infection with E. histolytica results in invasion of the intestine by the parasite, followed by tissue damage and inflammation. During this invasive process, parasites kill and phagocytose human epithelial cells, immune cells and erythrocytes. The more common path is commensal colonization, where trophozoites inhabit the gut lumen and feed on enteric bacteria by phagocytosis [7, 8].

IL-8 was secreted as potent chemokines from intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) visible to E. histolytica trophozoites, causing immune cell employment and infiltration of the intestinal epithelium and basement membrane [9]. One of the first immune cells to respond to amebic attacks were neutrophils. This is triggered via interferon-γ (IFN-γ), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), they liberate reactive oxygen species (ROS) which carry out an amebicidal activity in vitro [10, 11].

Although in the intestinal tract the mucosal layer commonly works as a prime physical barrier in contradiction to pathogens of the intestine, the immune response to the intestinal is the secondary protection against E. histolytica infestation. Immunoglobulins of mucosal (Among them, secretory IgA) were the main factor in the human intestinal protection mechanism [12].

In contrast to E. histolytica, cell-mediated immune responses are also important for host defense. In the early stages of infection, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) connect to and diagnose the carbohydrate recognition domain of the Gal/GalNAc lectin via toll-like receptor (TLR)-2/4, which activates NFκB and results in the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IFN-, and TNF-α [13, 14]. IFN- has been linked to the clearance of infection, whereas IL-4 and TNF- have been linked to illness [15, 16].

Studying the immune response to E. histolytica is very important to investigate the early diagnosis of this disease. Hence, this study aimed to culture E. histolytica in vitro from the stool samples of humans, and the stage of the cyst was purified.

Materials and Methods

A total of 818 human stool samples and 300 blood samples (The Sera were kept at-20°C until further use) were collected from a patient with diarrhea attended in ALfayhaa, Albasrah, Aljmhoree, Al-sader teaching hospitals, and private clinics in Basrah city from September 2017- August 2018.

Stool examination

The macroscopic examination will be done according to AL-Shaheen et al. [17].

Parasite propagation

-Culture method: All stipulation of culture was worked beneath the sterilization in laminar flow to prepare LES (Lock-egg slant medium) (NIH Modification of Boeock and Drboh lava’s mediums) [18] The stool samples were collected from patients with amoebic dysentery. The samples (6-8) were collected and preserved at room temperature until use around 48h the samples were passed through the following steps: Elimination; Examination; Establishment of Culture; Incubation; Examination of Culture media and Isolations. The culture if positive for amoeba and the pellet between the recipient tubes was split. This can be accomplished by chilling the culture tubes in an ice water bath for 5 minutes, overturning the culture tubes several times to detach adhering amoebae, and transferring the fluid phase to an empty culture tube containing 13mL of medium. In addition, incubation as the procedure above.

-Purification Cyst of E. histolytica: The cysts were purified by using two methods, the first method was through a culture medium (LES) of E. histolytica: After planting the E. histolytica in the LES took the liquid containing the cyst, and transferred to another sterile tube. Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) 2ml was added after the verification of purity and examination through the microscope and kept (-20) until use. The second method was done by the precoll gradient. From stool samples(human) cysts were purified as defined previously with some changes [19, 20] Most 4-5 g of pass try was dissolved in PBS, filtered through two layers of gauges, centrifuged at 3220g for 20 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded in the instrument. The pellet was suspended in 5mL of ethyl acetate (to separate the cyst from the fecal debris) and centrifuged at 3220g for 20 minutes after (working three times). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was cleaned three more times with PBS (at 3220g for 20 repetitions) before being suspended in 2mL of PBS. This was then carefully layered in 176×120mm, 15mL high-clarity polypropylene conical tubes using a chemist pipette on top of a previously braced 10-80% Percoll position by layering 2mLs each of 80% Percoll (in PBS), followed by 50%, 40%, 30%, 20%, and 10% Percoll solutions. This was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 32206g. The accumulation of the Percoll gradient between 40-80% was transferred to a fresh tube, cleaned three times with PBS, and microscopically examined for pure cysts.

Preparation of E. histolytica proteins

The cysts were purified by the two methods above, the cyst protein of E. histolytica was prepared in the following steps 2mL of PBS (pH: 7.2) was added to the vial containing (Purified cysts of E. histolytica) and glass beads, and the vortex was done for (10min). Each 2mL of suspension received 200 microliters of lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P40, 10Mm Tris-HCL, Aprotinen 0.1U/ml, 1% Triton X -100) for around 24 hours. after that, the suspension was taken and sonication for (15min) intervals (30secound) the speed was 20Khz by sonicate apparatus. Centrifugation was done to the suspension by cold centrifuge for (30 min) the speed was (10000 rpm). The supernatant was taken as the source of protein. Nanodrop apparatus was used to measure the concentration of proteins.

Antigens description

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis recognizes E.histolytica antigens (SDS-PAGE). Boiling in decreasing loading buffer (LB; 25% glycerol, 5% beta-Mercaptoethanol, 10% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), 0.01% Bromophenol Amytal in Tris/ HCl (PH=6.8) 16Mm) lyzed E. histolytica cysts protein (50 μg) per lane. Then, using a 6-10 slope gel, a detachment was performed using (SDS-PAGE). The polypeptide was electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (BA85; 0.4M; Scheleiche and Schull, Inc.). Trans blot transfer cell by the semi-liquid western blot apparatus, the nitrocellulose membrane was swayed for 15min, with transfer buffer and then was used in the suitable place in western blot apparatus. The nitrocellulose sheet containing the polypeptide was washed two times, for 5 minutes each time, with distilled water after being exposed to an electric current of 250 mA for two hours and a half at a temperature of 4 C. Washing the nitrocellulose sheet with Tris buffer saline-tween (TBS-T) PH=7.5 (10mM Tris-HCl, 154mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween -20) plus to 3% bovine serum albumin for 24 hours at 4°C blocked spare tight spots. On a rotator shaker, the nitrocellulose sheet was advanced clean three times, for five minutes each time.

The sheet was then cut into strips that were detached into an individual container and exposed to primary antibodies (Nine sera samples were prepared from a patient with diarrhea) to the E. histolytica for one hour. Following washing, the nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen, California, USA) directed against E. histolytica antibodies, rinsed (3x5 minutes) in TBS-T buffer, and then brooded in OPD (Ortho Phenyl domain) substrate solution for 15-20 minutes with rotating till the band appeared. The nitrocellulose strips were washed twice with distilled water to halt the reactivity.

Evaluation of interferon- γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) induced in a patient infected with E. histolytica

According to the industrialist directive, human serum samples were tested for IL-4 and IFN- using ELISA kits (Elabscience Inc.). Study groups related between patients and control, patients infection and acute infection, patients male and female, and related age of patients were studied. Using an ELISA plate reader, the optical densities of kit standards and test samples were measured at (450nm) (HumaReader HS, Human, Germany). Pictograms of IL-4 and IFN- per mL of material were used to explain the results.

Macroscopic examination and epidemiological study were done by Nassar et al. [21].

Findings

Culture medium was registered elevation and success in the isolating of E.histolytica from the stool specimen. Because of the growth and activity of Amoeba after 48 hours incubation of the first isolation after culture medium. The culture medium was obtained more than 3-6 times with better growth of standard Amoeba for the culture medium Table 1.

Table 1) Number of cyst and trophozoite (culture and subculture media) below laboratory situation

The pure cysts of E. histolytica were obtained by precoll gradient; the content isolated amid 80% and 40% of the percoll gradient. The numbers of the purified cysts of E. histolytica by culture media were more than the numbers of the cysts purified by gradients percoll but the purity of the cysts were better than from the culture medium Table 2.

Table 2) Number of the cysts of E.histolytica(by use culture medium or precoll gradient)

Antigens analysis

SDS-PAGE was used to separate cyst proteins, which yielded polypeptides for the assay. Coomassie blue was used to stain eleven polypeptides in particular. 101, 95, 80, 69, 64, 57, 51.2, 49, 36.1, 26.1, and 22.1kDa were their molecular weights (Figure 1a).

Western blot with molecular weight 83, 69, 61, 34, 29.1, 18.1, and 11.2kDa was identified with immune serum post-infection the protective immune responses, by E. histolytica parasite (Figure 1b). After electrophoretic disconnection of cysts proteins, the Immunoblot of proteins transmits from a 6-10% SDS-PAGE. Lane was immunoblotting of cysts extracts preparations probed with immune serum.

Figure 1) a:Proteins (SDS-PAGE); b: Antigens (western blot)

ELISA assay

Recorded data displayed significant differences at amidst study groups related between patients and control, and the recent results referred to the concentrations IL-4, IL-4 exhibited a significant increase in the concentration of amebic patients (171.0±262.0pg/ml) in comparison to control (48.0±47.0pg/ml) as in Figure 2a (p<0.05).

Figure 2) The concentrations of IL-4

Recorded data observed significant differences at p≤0.05 among the study groups related through patients infection and acute infection, the recent result the IL-4 exhibited a significant decrease (p≤0.05) in the concentration of amebic patients infection (77.0±146.0pg/ml) in comparison to patient acute (247.0±309.0pg/ml) concentrations of IL-4 in regarding as in Figure 2b.

There were no significant differences (p>0.05) between research groups based on the data collected related through male and females patients the recent result referred to the concentrations of IL-4, As shown in Figure 2c, the concentration of IL-4 in male patients (225±292pg/ml) was not significantly different (p>0.05) from patient female (118±216pg/ml).

Recorded data showed no significant differences between study groups related to the age of patients the recent result referred to the concentrations of IL-4, IL-4 exhibited no significant differences in the concentration of patients age 1-10 years (178.0±189.0pg/ml) in comparison to 10-25 years (231.0±327.0pg/ml), 25-40 years (120.0±178.0ng/ml), and 40> years (147±221pgml) as in Figure 2d.

IFN-Ɣ

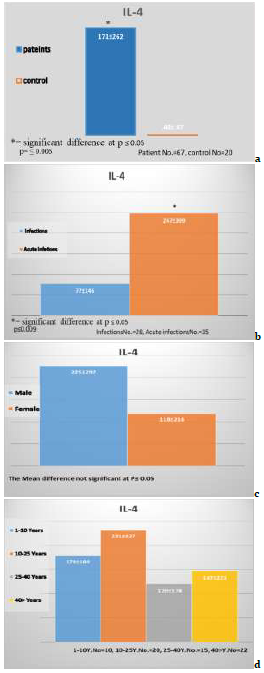

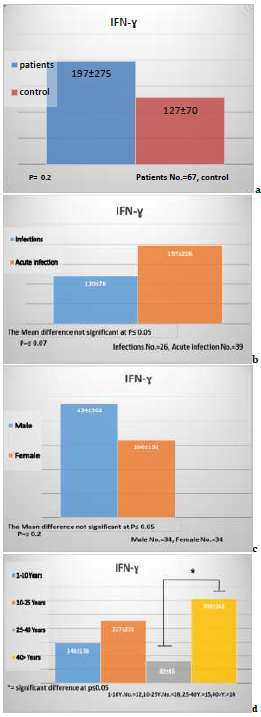

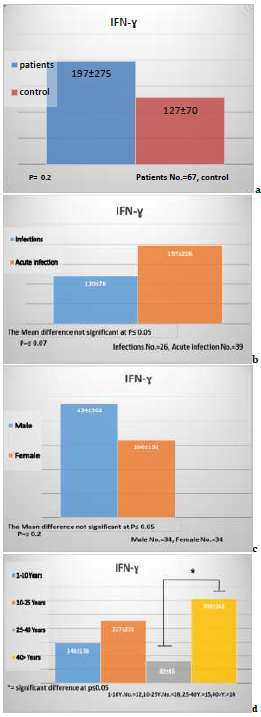

There were no significant differences at p≤0.05 between groups under study related to patients and control, and the recent result referred to the concentrations IFN-Ɣ, IFN-Ɣ exhibited significant differences (p≤0.05) in the concentration of amebic patients (197.0±275.0pg/ml) in comparison to control (127.0±70.0pg/ml) as in Figure 3a.

Recorded data showed no significant differences between study groups related to patients infection and Acute infection the recent result referred to the concentrations of IFN Ɣ -, IFN- Ɣ exhibited no significant decrease in the concentration of amebic patients infection (120.0±78.0pg/ml) in comparison to patient acute (197.0±206.0pg/ml) as in Figure 3b (p>0.05).

Recorded data showed no significant differences in gender at p≤0.05 between study groups related to patients male and patients female the recent result referred to the concentrations of IFN-Ɣ, IFN-Ɣ exhibited no significant differences in the concentration of patients male (234±362.0pg/ml) in comparison to patient female (160.0±132.0pg/ml) as in Figure 3c (p>0.05).

Recorded data showed no significant differences between study groups related to the age of patients the recent result referred to the concentrations of IL-Ɣ, IL- Ɣ Exhibited no significance in the concentration of patients aged 1-10 years (146.0±136.0ng/ml) in comparison to 10-25 years (227.0±211.0pg/ml), and significant differences at p≤0.05 between 25-40 years (80.0±45.0ng/ml) and 40> years (306.0±502.0pgml) as in Figure 3d (p>0.05).

Figure 3) The concentrations of IFN-Ɣ

Discussion

The results showed the success of isolating the E. histolytica from the stool and their development on the culture medium. It was confirmed that the Locke-egg medium (LEM) was one medium that shows a high accuracy in the diagnosis of amoeba from stool. After the successful development of ameba in the culture medium was obtained and the best E .histolytica population after the transfer (5-4) of transgenic culture medium, this was consistent with the studies also showed that the increase rate of the doubling of the stages of trophozoite and cyst 48-72 hour after vaccination in culture medium and then begins to decline and this was consistent with Dagci et al., [22]. The rate of replication reaches the highest level after 48 an hour of vaccination in the culture medium also research on the 72 hour incubation represents the A logarithm stage, which was harvest E. histolytica [23].

There is no cyst stage in the early hours if it was not exposed to environmental conditions and this was consistent with Eichinger [24] and Makioka et al. [25]. Several studies have indicated that it was necessary to provide the natural bacteria with natural germination if they cannot grow in the absence of bacterial growth. Bacteria E. coli were the most appropriate species in the axenic. Antibiotics are used to control bacterial growth and do not prevent the growth of natural bacteria in humans. There was just a balance between amoeba and bacteria. There was one strain of bacteria preferred [22]. It is the most common. The culture medium is naturally prepared from the bacteria found in the stool it was difficult to grow E. histolytica in the middle of the culture medium without being equipped with specific microorganisms controlled by antibiotics [26]. In terms of nutrient acquisition, the trophozoite stages produce large quantities of enzyme cysteine proteinase in the stages of the culture medium.

These enzymes are essential in the industry for the acquisition and consumption material of food by the culture medium was observed rapidly, leading to the loss of amoeba growth. Therefore, amoeba growth transports were available every (48-72) hours, the agricultural movements were every 48 hours to replace the nutrients of the culture medium, as much research has confirmed that antibiotics erythromycin are available in the medium to control bacterial growth sometimes.

On the parasite's plasma membrane, more than 20 proteins or families have been identified as open. EhADH112 and the cysteine proteinase EhCP112 (EhCP-B9), which var. a 112kDa adhesion catalyst, are allowed by these proteins [27, 28].

Eleven polypeptides were stained brightly with coomassie brilliant blue in the current investigation. The molecular weight of these molecules was 101, 95, 80, 69, 64, 57, 51.2, 49.1, 36.1, 26.1, and 22.1kDa. Another study discovered that when Western blots using excretory-secretory antigen (ESA) from axenically growing E. histolytica were probed with human serum, the results were positive. ESA antigenic proteins of 152, 131, 123, 110, 100, 82, and 76kDa were identified, each having multiple reactivities [29].

During E. histolytica infection, it has been found that the overexpressed genes are associated with the virulence mechanisms of the parasite or the host inflammatory reaction [30]. For the survival of E. histolytica in hepatic tissue, inflammation is necessary. It is the colonization by E. histolytica that would elicit the whole inflammatory process, which would lead to the progress of amoebic liver abscess (ALA) [31].

Evidence has shown that the presence of the parasite could stir up an immune response typified by the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators [32]. The serum level of IL-4 was substantially greater in patients with E. histolytica than in healthy controls in the current investigation. In the case of INF- γ, however, there was no significant difference in serum levels between E. histolytica patients and healthy controls. It can be deduced that the decrease in IFN-γ in patients with E. histolytica could signify the destruction of the Th-1 responses in acute amoebic infection. In other words, E. histolytica suppresses the production of nitric oxide by macrophages throughout a primary contagion and cytokine induction in the late stage of ALA [33]. The low INF- γ production could be explained by large increases in IL-4 production in patients infected with E. histolytica.

Indeed, the increase in IL-4 production in ALA patients is consistent with previous research that found increases in IL-4 and IL-10 production in symptomatic patients [33]. INF- γ, and IL-4, on the other hand, may have the ability to cause systemic immune suppression in E. histolytica infected patients, assisting in the progression of the clinical illness.

A substantial cell-mediated immune response against E. histolytica is required for amoebiasis resistance. E. histolytica's pathogenicity is based on its adherence to the intestinal epithelium, which is reinforced by its penetration into the mucosa. According to Guo et al. [34], previous studies revealed that cell-mediated immunity by IFN-γ plays a crucial function in immunity against amoebiasis, and could foretell the future vulnerability to symptomatic amoebiasis. Our study showed that the serum level of IL-4 was significantly higher in acute infection of E. histolytica as compared to primary infection. However, for INF-γ, there was no significant value of serum level in acute infection of E. histolytica as compared to primary infection. A Th-2 cell phenotype drives inflammation elicited by E. histolytica in the intestine.

The release of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 has different effects on amebic pathogenesis. This release of these cytokines could cause down-regulation of macrophage parasiticidal roles, leading to tissue damage via production of necrotizing enzymes [33]. E. histolytica has also been shown to inhibit both macrophage respiratory burst and antigen demonstration. Mucosal inflammation, which is triggered by Th-2 cytokines, aids in controlling the amoebic infection at an early stage, avoiding widespread damage.

It can be deduced that the decrease in patients with E. histolytica could signify the destruction of the Th-1 responses in acute amoebic infection. In other words, E. histolytica suppresses the production of nitric oxide via macrophages throughout a primary infection and cytokine initiation in the late stage of ALA [33]. The significant increases in IL-4 production in patients infected with E. histolytica may explain the low IFN-γ production. It is believed that the Th1 cytokine is the key to the control of invasive amoebiasis, while the production of macrophage downregulates cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, and could cause inhibition of cellular immune response to E. histolytica [34].

Our result shows that gender has no significant difference in the release of IL-4 and IFN-γ in patients through E. histolytica. Within a study to examine immune markers associated with asymptomatically infected and diseased E. histolytica patients in addition their association with sex, it was found that ALA patients showed high cytokine levels of IL-4 [35]. Furthermore, our study also showed that the release of IL-4 was not characterized by any significant difference in the following age ranges in patients with E. histolytica: 1-10 years; 10-25 years; 25-40 years; above 40 years. However, a significant difference was recorded in the release of IFN-γ according to Moraes et al. [36], when mononuclear cells from healthy people were treated with E. histolytica, IFN-γ and TGF were released. Our findings on the effects of IFN- γ are similar to Moraes' findings on the effects of IFN- γ. Based on the report of Gonzalez Rivas et al., concerning patients infected with E. histolytica, not only the production of IFN-γ and TGFβ and the increase in IL-4 were observed, but also a suppressive immune response was induced in patients with E. histolytica. The serum levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ play critical roles in the pathogenicity of amoebiasis [37].

More research is needed to distinguish pathogenic from nonpathogenic Entamoeba species using molecular diagnostics of intestinal E. histolytica. In addition, extraintestinal amebiasis in patients must be diagnosed in order to determine the disease's incidence at a national level.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the serum level of IL-4 was significantly higher in patients with E. histolytica associated with healthy observation collection by a significant difference of p≤0.05, while IFN-γ showed no significant difference. Also, study the immune response to E. histolytica cysts protein aide to investigate the early diagnosis of this disease.

Acknowledgments: We thank staff of Central Research Unit for their cooperation in western blot.

Ethical Permissions: This work was carried out with the approval of the Basrah Health Department.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Nassar SA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (25%); Al-Idreesi SR (Second Author), Methodologist/ Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (50%); Azzal GhY (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: This article was not supported by grants.

Recorded data showed no significant differences between study groups related to patients infection and Acute infection the recent result referred to the concentrations of IFN Ɣ -, IFN- Ɣ exhibited no significant decrease in the concentration of amebic patients infection (120.0±78.0pg/ml) in comparison to patient acute (197.0±206.0pg/ml) as in Figure 3b (p>0.05).

Recorded data showed no significant differences in gender at p≤0.05 between study groups related to patients male and patients female the recent result referred to the concentrations of IFN-Ɣ, IFN-Ɣ exhibited no significant differences in the concentration of patients male (234±362.0pg/ml) in comparison to patient female (160.0±132.0pg/ml) as in Figure 3c (p>0.05).

Recorded data showed no significant differences between study groups related to the age of patients the recent result referred to the concentrations of IL-Ɣ, IL- Ɣ Exhibited no significance in the concentration of patients aged 1-10 years (146.0±136.0ng/ml) in comparison to 10-25 years (227.0±211.0pg/ml), and significant differences at p≤0.05 between 25-40 years (80.0±45.0ng/ml) and 40> years (306.0±502.0pgml) as in Figure 3d (p>0.05).

Figure 3) The concentrations of IFN-Ɣ

Discussion

The results showed the success of isolating the E. histolytica from the stool and their development on the culture medium. It was confirmed that the Locke-egg medium (LEM) was one medium that shows a high accuracy in the diagnosis of amoeba from stool. After the successful development of ameba in the culture medium was obtained and the best E .histolytica population after the transfer (5-4) of transgenic culture medium, this was consistent with the studies also showed that the increase rate of the doubling of the stages of trophozoite and cyst 48-72 hour after vaccination in culture medium and then begins to decline and this was consistent with Dagci et al., [22]. The rate of replication reaches the highest level after 48 an hour of vaccination in the culture medium also research on the 72 hour incubation represents the A logarithm stage, which was harvest E. histolytica [23].

There is no cyst stage in the early hours if it was not exposed to environmental conditions and this was consistent with Eichinger [24] and Makioka et al. [25]. Several studies have indicated that it was necessary to provide the natural bacteria with natural germination if they cannot grow in the absence of bacterial growth. Bacteria E. coli were the most appropriate species in the axenic. Antibiotics are used to control bacterial growth and do not prevent the growth of natural bacteria in humans. There was just a balance between amoeba and bacteria. There was one strain of bacteria preferred [22]. It is the most common. The culture medium is naturally prepared from the bacteria found in the stool it was difficult to grow E. histolytica in the middle of the culture medium without being equipped with specific microorganisms controlled by antibiotics [26]. In terms of nutrient acquisition, the trophozoite stages produce large quantities of enzyme cysteine proteinase in the stages of the culture medium.

These enzymes are essential in the industry for the acquisition and consumption material of food by the culture medium was observed rapidly, leading to the loss of amoeba growth. Therefore, amoeba growth transports were available every (48-72) hours, the agricultural movements were every 48 hours to replace the nutrients of the culture medium, as much research has confirmed that antibiotics erythromycin are available in the medium to control bacterial growth sometimes.

On the parasite's plasma membrane, more than 20 proteins or families have been identified as open. EhADH112 and the cysteine proteinase EhCP112 (EhCP-B9), which var. a 112kDa adhesion catalyst, are allowed by these proteins [27, 28].

Eleven polypeptides were stained brightly with coomassie brilliant blue in the current investigation. The molecular weight of these molecules was 101, 95, 80, 69, 64, 57, 51.2, 49.1, 36.1, 26.1, and 22.1kDa. Another study discovered that when Western blots using excretory-secretory antigen (ESA) from axenically growing E. histolytica were probed with human serum, the results were positive. ESA antigenic proteins of 152, 131, 123, 110, 100, 82, and 76kDa were identified, each having multiple reactivities [29].

During E. histolytica infection, it has been found that the overexpressed genes are associated with the virulence mechanisms of the parasite or the host inflammatory reaction [30]. For the survival of E. histolytica in hepatic tissue, inflammation is necessary. It is the colonization by E. histolytica that would elicit the whole inflammatory process, which would lead to the progress of amoebic liver abscess (ALA) [31].

Evidence has shown that the presence of the parasite could stir up an immune response typified by the secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators [32]. The serum level of IL-4 was substantially greater in patients with E. histolytica than in healthy controls in the current investigation. In the case of INF- γ, however, there was no significant difference in serum levels between E. histolytica patients and healthy controls. It can be deduced that the decrease in IFN-γ in patients with E. histolytica could signify the destruction of the Th-1 responses in acute amoebic infection. In other words, E. histolytica suppresses the production of nitric oxide by macrophages throughout a primary contagion and cytokine induction in the late stage of ALA [33]. The low INF- γ production could be explained by large increases in IL-4 production in patients infected with E. histolytica.

Indeed, the increase in IL-4 production in ALA patients is consistent with previous research that found increases in IL-4 and IL-10 production in symptomatic patients [33]. INF- γ, and IL-4, on the other hand, may have the ability to cause systemic immune suppression in E. histolytica infected patients, assisting in the progression of the clinical illness.

A substantial cell-mediated immune response against E. histolytica is required for amoebiasis resistance. E. histolytica's pathogenicity is based on its adherence to the intestinal epithelium, which is reinforced by its penetration into the mucosa. According to Guo et al. [34], previous studies revealed that cell-mediated immunity by IFN-γ plays a crucial function in immunity against amoebiasis, and could foretell the future vulnerability to symptomatic amoebiasis. Our study showed that the serum level of IL-4 was significantly higher in acute infection of E. histolytica as compared to primary infection. However, for INF-γ, there was no significant value of serum level in acute infection of E. histolytica as compared to primary infection. A Th-2 cell phenotype drives inflammation elicited by E. histolytica in the intestine.

The release of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 has different effects on amebic pathogenesis. This release of these cytokines could cause down-regulation of macrophage parasiticidal roles, leading to tissue damage via production of necrotizing enzymes [33]. E. histolytica has also been shown to inhibit both macrophage respiratory burst and antigen demonstration. Mucosal inflammation, which is triggered by Th-2 cytokines, aids in controlling the amoebic infection at an early stage, avoiding widespread damage.

It can be deduced that the decrease in patients with E. histolytica could signify the destruction of the Th-1 responses in acute amoebic infection. In other words, E. histolytica suppresses the production of nitric oxide via macrophages throughout a primary infection and cytokine initiation in the late stage of ALA [33]. The significant increases in IL-4 production in patients infected with E. histolytica may explain the low IFN-γ production. It is believed that the Th1 cytokine is the key to the control of invasive amoebiasis, while the production of macrophage downregulates cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, and could cause inhibition of cellular immune response to E. histolytica [34].

Our result shows that gender has no significant difference in the release of IL-4 and IFN-γ in patients through E. histolytica. Within a study to examine immune markers associated with asymptomatically infected and diseased E. histolytica patients in addition their association with sex, it was found that ALA patients showed high cytokine levels of IL-4 [35]. Furthermore, our study also showed that the release of IL-4 was not characterized by any significant difference in the following age ranges in patients with E. histolytica: 1-10 years; 10-25 years; 25-40 years; above 40 years. However, a significant difference was recorded in the release of IFN-γ according to Moraes et al. [36], when mononuclear cells from healthy people were treated with E. histolytica, IFN-γ and TGF were released. Our findings on the effects of IFN- γ are similar to Moraes' findings on the effects of IFN- γ. Based on the report of Gonzalez Rivas et al., concerning patients infected with E. histolytica, not only the production of IFN-γ and TGFβ and the increase in IL-4 were observed, but also a suppressive immune response was induced in patients with E. histolytica. The serum levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ play critical roles in the pathogenicity of amoebiasis [37].

More research is needed to distinguish pathogenic from nonpathogenic Entamoeba species using molecular diagnostics of intestinal E. histolytica. In addition, extraintestinal amebiasis in patients must be diagnosed in order to determine the disease's incidence at a national level.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the serum level of IL-4 was significantly higher in patients with E. histolytica associated with healthy observation collection by a significant difference of p≤0.05, while IFN-γ showed no significant difference. Also, study the immune response to E. histolytica cysts protein aide to investigate the early diagnosis of this disease.

Acknowledgments: We thank staff of Central Research Unit for their cooperation in western blot.

Ethical Permissions: This work was carried out with the approval of the Basrah Health Department.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Nassar SA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (25%); Al-Idreesi SR (Second Author), Methodologist/ Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (50%); Azzal GhY (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: This article was not supported by grants.

Keywords:

References

1. Fletcher SM, Stark D, Harkness J, Ellis J. Enteric protozoa in the developed world: a public health perspective. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(3):420-49. [Link] [DOI:10.1128/CMR.05038-11]

2. Kelly P. Protozoal gastrointestinal infections. Medicine. 2013;41(12):705-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mpmed.2013.09.003]

3. Monzote L, Siddiq A. Drug development to protozoan diseases. Open Med Chem J. 2011;5:1-3. [Link] [DOI:10.2174/1874104501105010001]

4. Lebbad M, Svard SG. PCR differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar from patients with amoeba infection initially diagnosed by microscopy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37(9):680-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00365540510037812]

5. Ohnishi K, Kato Y, Imamura A, Fukayama M, Tsunoda T, Sakaue Y, et al. Present characteristics of symptomatic Entamoeba histolytica infection in the big cities of Japan. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132(1):57-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S0950268803001389]

6. Xim'enez C, Mor'an P, Rojas L, Valadez A, Gomez A. "Reassessment of the epidemiology of amebiasis: state of the art," Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 2009;9(6):1023-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.06.008]

7. Voigt H, Olivo JC, Sansonetti P, Guillén N. Myosin IB from Entamoeba histolytica is involved in phagocytosis of human erythrocytes. J Cell Sci. 1999; 112 (Pt 8):1191-201. [Link] [DOI:10.1242/jcs.112.8.1191]

8. Wilson IW, Weedall GD, Hall N. Host-parasite interactions in Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar: What have we learned from their genomes?. Parasite Immunol. 2012;34(2-3):90-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01325.x]

9. Yu Y, Chadee K. Entamoeba histolytica stimulates interleukin 8 from human colonic epithelial cells without parasite-enterocyte contact. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(5):1536-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70035-0]

10. Guerrant RL, Brush J, Ravdin JI, Sullivan JA, Mandell GL. Interaction between Entamoeba histolytica and human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:83-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/infdis/143.1.83]

11. Denis M, Chadee K. Human neutrophils activated by interferongamma and tumour necrosis factor-alpha kill Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 1989;46:270-274. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jlb.46.3.270]

12. Guo X, Barroso L, Lyerly DM, Petri Jr WA, Houpt ER. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell- and IL-17-mediated protection against Entamoeba histolytica induced by a recombinant vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29(4):772-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.013]

13. Gay NJ, Gangloff M. Structure and function of toll receptors and their ligands. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:141-65. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.151318]

14. Galvan-Moroyoqui JM, Del CarmenDomínguez-Robles M, Meza I. Pathogenic bacteria prime the induction of toll-like receptor signalling in human colonic cells by the Gal/GalNAc lectin carbohydrate recognition domain of Entamoeba histolytica. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41(10):1101-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.06.003]

15. Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by the innate immune sys-tem. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30:16-34. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/08830185.2010.529976]

16. Sanchez-Guillen M. del. C, Perez-Fuentez R, Salgado-Rosas H, Ruiz-Arguelles A, Ackers J, Shire A, Talmas-Rohana P. Differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica /Entamoeba dispar by PCR and their correlation with humoral and cellular immunity in individuals with clinical variants of amoebiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66(6):731-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.731]

17. Al-Shaheen Z, Al-Maki AK, Hussein K. A study on prevalence of Entamoeba histolytica & Giardia lamblia infection among patient attending Qurna hospital in Basrah. Basrah J Vet Res. 2007;6:30-6. [Link] [DOI:10.33762/bvetr.2007.55769]

18. Al-Idreesi SR, Al-Azizz S, Azzal Gh, Hisab A. Culture of Entamoeba histolytica in vitro. AL-Qadisiya J Vet Med Sci. 2008;7(1). [Link]

19. Weber R, Bryan RT, Juranek DD. Improved stool concentration procedure for detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(11):2869-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1128/jcm.30.11.2869-2873.1992]

20. Segovia-Gamboa NC, Chavez-Mongolia B, Medina-Flores Y, Cazares-Raga FE, Hernandez-Ramirez VI. Entamoeba invadens, encystation process and enolase. Exp Parasitol. 2010;125:63-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.exppara.2009.12.019]

21. Nassar SA, Al-Idreesi SR, Al-Emaara GY. Epidemiological study of Entameoba histolytica in Basrah city -southern of Iraq. Bas J Vet Res. 2019;18(2). [Link]

22. Dagci H, Balcioglu IC, Ertabaklar H, Kurt O, Atambay M. Effectiveness of peptone-yeast extract (P-Y) medium in the cultivation and isolation of Entamoeba histolytica/Entamoeba dispar in Turkish patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;45(2):127-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0732-8893(02)00508-4]

23. Clark CG, Diamond LS. Methods for cultivation of luminal parasitic protists of clinical importance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(3):329-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1128/CMR.15.3.329-341.2002]

24. Eichinger D. A role for a galactose lectin and its ligands during encystment of Entamoeba. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2001;48(1):17-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00411.x]

25. Makioka A, Kumagai M, Ohtomo H, Kobayashi S, Takeuchi T. Effect of calcium antagonists, calcium channel blockers and calmodulin inhibitors on the growth and encystations of Entamoeba histolytica and E. invadens. Parasitol Res. 2001;87:833-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s004360100453]

26. Que X, Reed SL. Cysteine proteinases and the pathogenesis of amebiasis. J Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(2):196-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1128/CMR.13.2.196]

27. Garcia-Rivera G, Rodriguez MA, Ocadiz R, Martinez-Lopez MC, Arroyo R, Gonzalez-Robles A, Orozco E. Entamoeba histolytica: a novel cysteine protease and an adhesin form the 112 kDa surface protein. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33(3):556-68. [Link] [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01500.x]

28. Banuelos C, Garcia-Rivera G, Lopez-Reyes I, Mendoza L, Gonzalez-Robles A, Herranz S, et al. EhADH112 is a Bro1 domain-containing protein involved in the Entamoeba histolytica multivesicular bodies pathway. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:657942. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2012/657942]

29. Wong WK, Tan ZN, Othman N, Lim BH, Mohamed Z, Olivos Garcia A, Noordin R. Analysis of Entamoeba histolytica excretory-secretory antigen and identification of a new potential diagnostic marker. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(11):1913-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1128/CVI.05356-11]

30. Min X, Feng M, Guan Y, Man S, Fu Y, Cheng X, et al. Evaluation of the C-terminal fragment of Entamoeba histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin intermediate subunit as a vaccine candidate against amebic liver abscess. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004419. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004419]

31. Mortimer L, Chadee K. The immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126(3):366-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.exppara.2010.03.005]

32. Pacheco-Yépez J, Rivera-Aguilar V, Barbosa-Cabrera E, Rojas Hernández S, Jarillo-Luna RA, Campos-Rodríguez R. Myeloperoxidase binds to and kills Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Parasite Immunol. 2011;33(5):255-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01275.x]

33. Rafiei A, Ajami A, Hajilooi M, Etemadi A. Th-1/ Th-2 cytokine pattern in human amoebic colitis. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12(20):1376-80. [Link] [DOI:10.3923/pjbs.2009.1376.1380]

34. Guo X, Barroso L, Becker SM, Lyerly DM, Vedvick TS, Reed SG, et al. Protection against intestinal amebiasis by a recombinant vaccine is transferable by T cells and mediated by gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 2009;77(9):3909-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1128/IAI.00487-09]

35. Bernin H, Marggraff C, Jacobs T, Brattig N, van AN L, Blessmann J, et al. Immune markers characteristic for asymptomatically infected and diseased Entamoeba histolytica individuals and their relation to sex. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:621. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12879-014-0621-1]

36. Moraes LC, Al França EL, Pessoa RS, Fagundes DLG, Hernandes MG, PRibeiro V, et al. The effect of IFN-γ and TGF-β in the functional activity of mononuclear cells in the presence of Entamoeba histolytica. Parasites Vect. 2015;8:413. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13071-015-1028-6]

37. Gonzalez Rivas E, Ximenez C, Nieves-Ramirez ME, Moran Silva P, Partida-Rodríguez O, Hernandez EH, et al. Entamoeba histolytica calreticulin induces the expression of cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with amebic liver abscess. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:358. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2018.00358]