Volume 13, Issue 2 (2021)

Iran J War Public Health 2021, 13(2): 115-124 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/08/9 | Accepted: 2021/08/25 | Published: 2021/10/2

Received: 2021/08/9 | Accepted: 2021/08/25 | Published: 2021/10/2

How to cite this article

Sajadi H, Shirazikhah M, Nazari M, Sajadi F, Setareh Forouzan A, Jorjoran Shushtari Z. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Persons with Disabilities towards COVID-19: Evidence from the Islamic Republic of Iran. Iran J War Public Health 2021; 13 (2) :115-124

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-988-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-988-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

H.S. Sajadi1, M. Shirazikhah *2, M. Nazari3, F.S. Sajadi4, A. Setareh Forouzan5, Z. Jorjoran Shushtari2

1- Knowledge Utilization Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- University Research and Development Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran

5- Social Welfare Management Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- University Research and Development Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran

5- Social Welfare Management Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (1146 Views)

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has significantly affected people's lives [1], particularly those who were vulnerable [2]. Persons With Disabilities (PWDs) are among vulnerable groups due to different factors such as; lack of access to resources, social isolation, their dependence on others for care and support [3]. During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, PWDs are at greater risk of dying due to preventable factors and the inability to seek help and access health services. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has spotlighted another systemic vulnerability for PWDs: limited access to health information [4]. Poor access to information among PWDs causes limitations in complying with public health protocols [5]. Thus, it is strongly recommended that COVID-19 risk reduction strategies include PWDs to avoid discrimination and necessitate covering PWDs to achieve universal health coverage [6].

The impact of COVID-19 on PWDs was mainly investigated by scholars to highlight the importance of prioritizing these groups and their problems and challenges [7-12]. However, scant evidence is available to guide how to support PWDs during pandemics [13]. Increasing knowledge, improving attitudes, and practice are helpful to increase precautionary behaviors among PDWs [14], particularly will help them to prevent from getting infected with COVID-19. Moreover, PWD's adherence to the control measures is largely affected by their KAP (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices) towards COVID-19 in accordance with KAP theory. Thus, unequal access to health information and announced health instructions for PWDs are fundamental challenges during pandemics [6, 15, 16]. While educational content news and information about COVID-19 are generally designed for the whole society, it's difficult or almost impossible for PWDs to access and utilize them.

To address this challenge, Iran has taken measures to inform PWDs, as part of its plan to respond to COVID-19. For instance, a practical guideline of COVID-19 for PWDs was developed and distributed to inform PWDs towards COVID-19 prevention [17]. It was expected that this guideline provides applicable information and assists PWDs in protecting themselves and improving their adherence to preventive measures.

To our knowledge, there were no data on KAP about COVID-19 in PWDs. Thus, this study aimed to explore the level of KAP in PWD's related to COVID-19 and identify obstacles and facilitators of promoting their KAP.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-qualitative study was conducted in two phases on PWDs in Iran in 2020.

Quantitative phase

Descriptive-cross sectional phase was carried out on all PWDs in Iran. The sample size was calculated using a confidence interval of 95% and an error of 3%, which yielded a sample size of 1067. Respondents were selected using a convenience sampling technique. According to the estimated population of PWDs in each province, the number of samples for each province was determined. We uploaded the questionnaire to the Porsline website, an online questionnaire system widely used in academic study in Iran. Then, we shared the questionnaire link generated by Porsline to the WhatsApp and Email of all managers of the Campaign to Support PWDs and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in the field of PWDs in all 31 provinces of the country and asked them to select PWDs randomly and invite them to fill in the questionnaire. The link was subsequently forwarded by these contacts to more PWDs to fill in the questionnaire. IP address restriction technology was adopted to ensure users with the same IP address could only complete the questionnaire once. Our inclusion criteria included membership in the Campaign, access to social media, ability to complete an online questionnaire, and willingness to participate in the study.

Data were collected using a self-administered researcher-made online questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of two main sections: (a) demographic characteristics (11 items); and (b) measuring knowledge (6 items), attitude (6 items), and practice (6 items) of the target population, as well as items on access to and applicability of educational materials related to COVID-19 (4 items). Items related to knowledge (e.g., the main symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, fatigue, dry cough, and aches) had three options of "true", "False", "I don't know," while items on attitude (e.g., in my opinion, early diagnosis of COVID-19 can lead to recovery and successful treatment) were scored on a three-point Likert scale, "agree", "disagree", "don't know." Items on practice (e.g., have you been to a crowded place in recent days) and access to educational content also had two options: "Yes", "No". The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by obtaining the opinions of three experts in rehabilitation services. Reliability was evaluated using a pilot study with a sample of 30 subjects and the McDonald's omega coefficient. The value of this coefficient for items related to knowledge, attitude, and practice was 0.86, 0.86, and 0.85, respectively. Each item had a score of 1 to 20. Scores higher than 15 were categorized as "good," between 10 to 15 as "moderate," and less than ten as "weak."

The approval for this study was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. After finalizing the

questionnaire, it was available through the Porsline platform. The questionnaire was available for an entire month (May 9- June 9, 2020), which required seven minutes of overage to be filled.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software. Since data were not normally distributed, two nonparametric tests, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis, were used.

Qualitative phase

This part is intended to identify obstacles and facilitators of promoting the PWDs' KAP using a qualitative approach in July and August 2020. Participants were PWDs who were selected by a purposive sampling method. These participants were different from those who took part in the previous phase. Researchers tried to include people with different experiences and achieve maximum gender, age, education, and socio-economic status. The sampling was stopped upon reaching data saturation, which was 32 interviews. The inclusion criteria included the ability and willingness to participate in the study.

Data were collected using online semi-structured interviews. The interview guide was developed, piloted, and finalized based on the feedback.

The approval for this section of the study was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. The interviews were conducted by a trained interviewer. At the end of the interview, contact means were determined for further communications, if needed. The interviews were all audio-recorded by a Voice Recorder (Sony ICD-UX570), transcribed. Analyzing the interviews was conducted simultaneously with the data collection process. The transcripts were reviewed several times, and then meaning codes were extracted by two researchers independently. Afterward, themes and sub-themes were extracted, and frequent meetings were held to discuss the themes and sub-themes. Discrepancies were resolved via prolonged discussions.

Findings

Quantitative phase

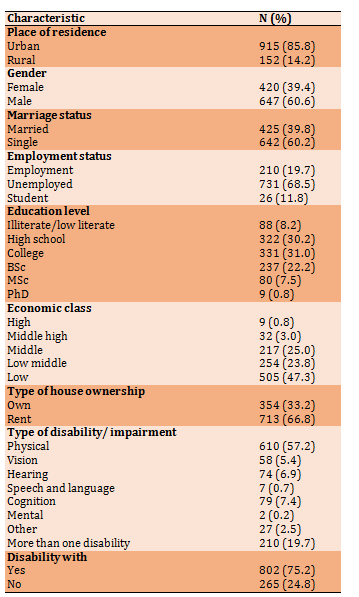

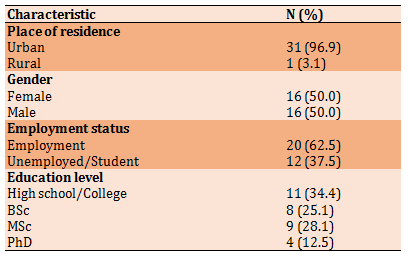

In total, 1067 questionnaires were filled and analyzed. The mean±SD of participants' age was 36.8±15.2, and the duration of being disabled was 24.6±15.0 (Table 1).

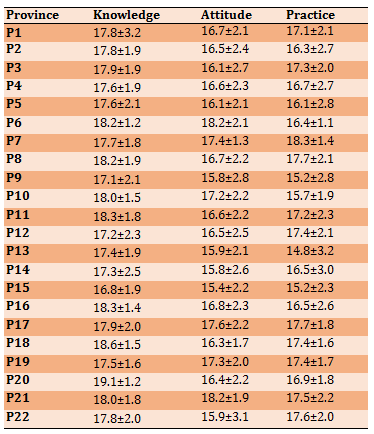

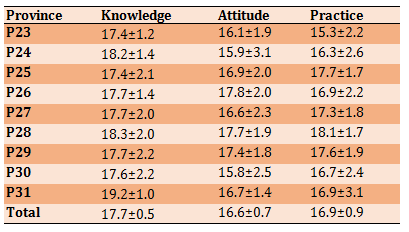

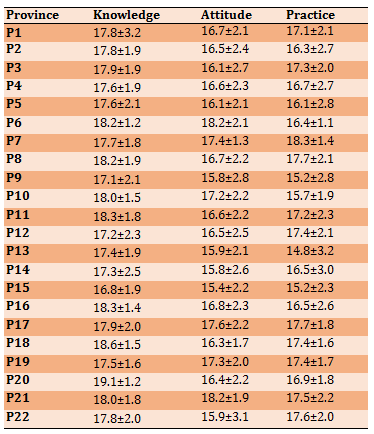

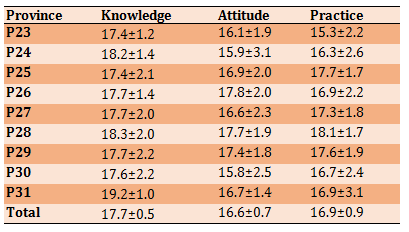

The KAP mean±SD scores of PWDs concerning COVID-19 separated by province were provided in Table 2. There was a significant difference between provinces concerning the KAP score (p<0.05). The level of KAP was good for the whole country. There was a significant difference between the mean±SD scores of KAP (p<0.05).

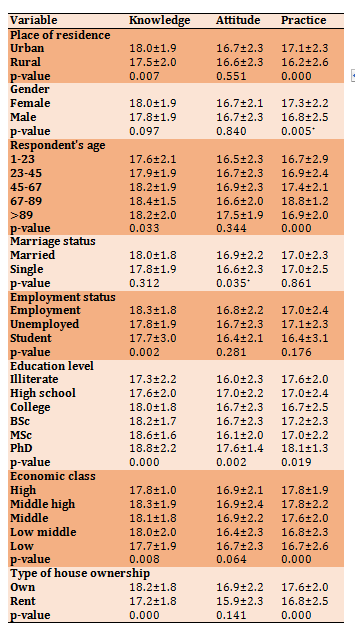

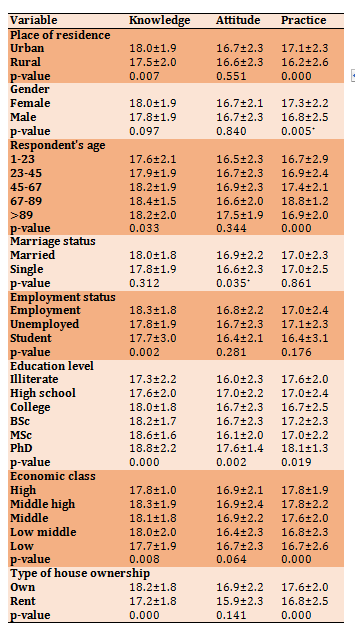

The mean score of knowledge was higher than attitude and practice, while there was no significant difference between attitude and practice scores (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 1) Participant’s demographic characteristics (N=1067)

Table 2) Results of mean±SD of knowledge, attitude, and practices of PWDs concerning COVID-19 (n=1067)

Continue of Table 2) Results of mean±SD of knowledge, attitude, and practices of PWDs concerning COVID-19 (n=1067)

Table 3) Results of the relationship between demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitude, and practices of persons with disabilities concerning COVID- 19 (Mean±SD)

Qualitative phase

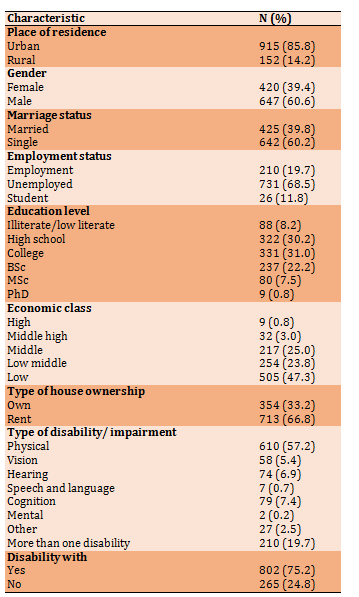

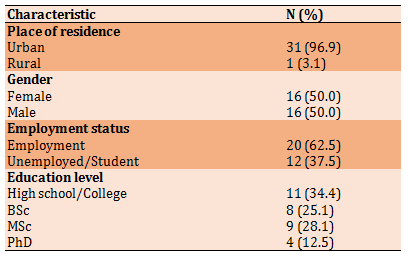

In this study, 32 interviews were performed, which on average lasted 38.1 minutes (with a range from 7 to 84 Minutes). The mean age of participants was 43.9±11.3 years. Demographic information of the interviewee is provided in Table 4.

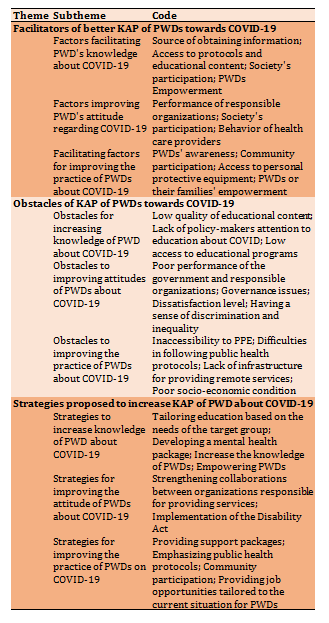

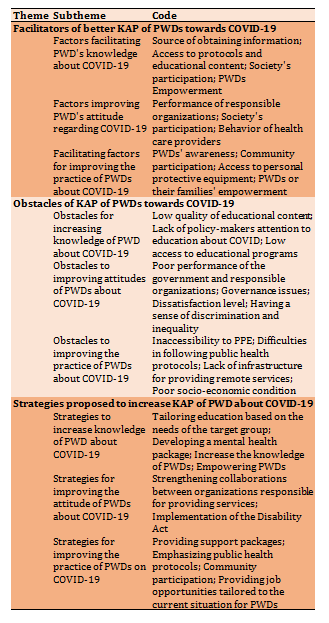

One hundred sixty-one codes were identified, categorized into three themes and nine subthemes (Table 5).

Table 4) Respondent’s demographic characteristics (n=32)

Table 5) Themes and subthemes related to facilitators and barriers of knowledge, attitude, and practices of persons with disabilities concerning COVID- 19

Theme 1: Facilitators of better KAP of PWDs towards COVID-19

-Factors facilitating PWD's knowledge about COVID-19: Almost all respondents mentioned using one or more sources to obtain news, information, and educational content regarding COVID-19. The most important source of obtaining information is social media, according to the interviews. Social networks established in WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram played a leading role in delivering relevant educational content information to PWDs. Respondents also mentioned national broadcasting, especially national TV, as a primary source of information. Very few people also mentioned receiving news and information from international broadcasting. For some participants, several health organizations such as medical universities, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME), or the World Health Organization were the primary educational information sources. Some people noted the developed COVID- 19 self-assessment systems by the MoHME and their subsequent follow-ups as important information sources. A few respondents also mentioned organizations such as the Welfare Organization, the Ministry of Education, and provincial governments as the primary source of information. Interestingly, very few respondents had actively obtained information about the disease even before the official announcement of the COVID-19 news.

"As soon as the pandemic spread in Iran, we created a news channel on WhatsApp to educate PWDs—most of them are heads of households—in this regard. Fortunately, we have many educated people in Bandar Abbas, and we provided them with educational videos and requested to keep themselves updated with the latest shared information. University communities also helped us in this way." (M5)

Respondents also mentioned access to protocols and educational content specifically designed for COVID-19 as facilitators to increase awareness. Besides, protocols are developed for the whole society, both PWDs and other people. In addition to informing others, PWDs, and society's participation in developing educational content has a crucial role in increasing the awareness of PWDs. Since educational content, news, and information about COVID-19 are generally designed for the whole society; it's difficult or almost impossible for PWDs to access them. Hence, PWDs or related associations began to develop content tailored to this target group. In addition to education, these public organizations also began to use appropriate communication channels and broadcasting, primarily for PWDs, which has an essential role in increasing the awareness of PWDs. Another form of public participation to raise awareness of PWDs was the voluntary counseling of some physicians and health workers, who were focused on answering their questions and providing them with the necessary information. The last facilitator was the empowerment of PWDs. Those PWDs from high socio-economic classes had a higher level of awareness about COVID-19, mainly due to their characteristics and better access to educational content.

-Factors that improve attitude PWDs regarding COVID-19: According to participants, the excellent practice of responsible organizations and agencies improved the attitude of PWDs toward COVID-19. Society's active participation in managing the pandemic has also been considered a facilitator. Participants noted that continuous participation of NGOs, donors, and friendly relationships between members of social networks, caused PWDs in small groups to connect and share their fears and experiences to create and maintain more hopeful views. Another facilitator was the sound and respectful behavior of health care providers, which addressed their concerns about inadequate services during the pandemic.

"Ministry of Health, national broadcasting, and Red Crescent Organization appropriately reacted. They informed, educated, and provided care to PWDs, eventuated in satisfaction and positive vision towards them" (M8).

-Facilitating factors for improving the practice of PWDs about COVID-19: Participants mentioned increased awareness as the most important facilitator of observing public health protocols. Community participation was another facilitator mentioned by almost all participants. Community participation can be in the form of providing assistance and support packages, educational and information services (tailored to the PWDs' needs), and monitoring and following up on the status of PWDs. This factor has facilitated taking care of PWDs infected with COVID-19. Besides, it was also useful for mobilizing society to provide supportive packages for the poor.

Another important facilitator is access to personal protective equipment (PPE). Although initially, it was challenging to find PPEs, it gradually became easy as the country expanded its production and distribution network. Meanwhile, affordability is another critical issue that should be considered. PWDs or their families' empowerment was another critical factor for good practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"We were gathering every month in our conference hall, but now everything is online." (M5)

Theme 2: Obstacles of KAP of PWDs towards COVID-19

-Obstacles for increasing knowledge of PWD about COVID-19: Although the level of knowledge of PWDs about COVID-19 was satisfactory, participants mentioned substantial obstacles. While PWDs have tried to develop educational content tailored to their special needs, such contents were not coherent enough to be understandable. Another challenge noted by participants was ignorance or neglect of policy-makers in providing proper and continuous education about COVID- 19 to PWDs. Participants believed that the health authorities were mostly focused on training the whole society or high-risk groups, and there was no plan for PWDs. Even though the elderly were introduced as a high-risk group for COVID-19 infection, sufficient attention is not paid. Low quality of educational content was also a significant challenge noted by participants. False information regarding controlling or preventing the disease may disrupt increasing the awareness of PWDs. Insufficient access to educational programs and content due to not using appropriate messages to PWDs was another obstacle.

"No, it wasn't. They also should provide special training to PWDs through national TV, which is ignored. For example, what protocols should be implemented by a blind person when s/he is out of the home to avoid COVID-19 infection." (M4)

Obstacles to improving attitudes of PWDs about COVID-19: According to participants, the negative view of PWDs about COVID-19 was mostly due to the government's poor performance and responsible organizations in providing services to PWDs. Almost all participants mentioned these organizations' inadequate agility and access to services as the main reasons for their disappointment. Other identified obstacles are mostly related to governance issues. One of these obstacles was the lack of data and information about PWDs in some organizations and lack of trust in the reports, statistics, and information announced by some relevant organizations about the COVID-19 patients in Iran and assistance and care provided to PWDs. Moreover, the lack of transparency in the performance of responsible organizations has intensified the dissatisfactions of PWDs.

Another obstacle was the low accountability of the responsible organizations in addressing society's problems, especially PWDs. Lack of accountability has caused disappointment among PWDs so that they were disappointed with any fundamental change. Also, they mentioned not implementing the Disability Law, which was enacted several years ago, as another reason for their dissatisfaction. While before the outbreak, PWDs considered their demands forgotten in the policies, participants of this study believed the COVID-19 pandemic had intensified this problem. Besides, given the absence of defined guidelines and mechanisms for monitoring rehabilitation equipment, PWDs considered the government unable to manage the pandemic effectively.

Although most participants described community participation as an influential factor in creating a positive view of the future, some participants expressed dissatisfaction with some associations. Some participants' misunderstanding about NGOs and government agencies' defined roles and responsibilities led to their unsound expectations reflected in this study. The last obstacle was discrimination and inequality in providing routine rehabilitation services and services and care related to COVID-19. With a sense of second-class citizenship, most of them always feel a sense of discrimination in providing services to PWDs.

"They didn't send any information to the Welfare Organization about the number of PWDs who have been infected with COVID-19, to provide support packages to those in need, or national broadcasting. But we are not a priority for them." (M10)

-Obstacles to improving the practice of PWDs about COVID-19: The most critical obstacle to implementing public health advice by PWDs was the inaccessibility of PPE. Although it was tried to address this problem by mobilizing society, it was insufficient and could not provide everyone access. Participants mentioned inaccessibility in financial and physical access, so buying PPEs was not affordable for many despite the low price.

"It was both rationed and expensive. Disposable gloves and a small bottle of disinfectants, and there was an alcohol and a mask." (M12)

Difficulties in following public health protocols by PWDs was another significant obstacle noted by participants, particularly for those with severe physical disabilities or intellectual disabilities. The lack of infrastructure for providing remote services was another challenge noted by participants. They believed many services could be provided through online platforms. In this case, there was no need to refer to rehabilitation centers, which are in line with public health protocols. However, few people noted receiving online services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The last obstacle was the poor economic condition and the need to provide living expenses, which led them to go into the community to meet their needs despite recommendations to stay at home. However, some cases had no option except to go to their workplace.

Themes 3: Strategies proposed to increase KAP of PWD about COVID-19

Strategies to increase knowledge of PWD about COVID-19: Many participants emphasized that educational content should be developed based on the target group's needs. However, attention should be paid to the needs of PWDs with a history of COVID-19 infection. According to the PWDs' needs, another effective measure would be developing a mental health package, including promoting or maintaining PWDs' mental health. Increase the knowledge of PWDs and respecting their specific needs were other strategies proposed by participants. In this way, we can increase society's participation in meeting some educational needs of PWDs. Empowering PWDs was another strategy proposed by participants. As it's an effective strategy, it can significantly impact increasing awareness of PWDs. Moreover, they mentioned expanding collaborations and facilitating informing and educating PWDs during crises.

"New crises will emerge, and COVID-19 won't be the last. Therefore, we have to be prepared. A crisis Management Organization is established for this purpose. Enabling PWDs to provide first aid, or training rescue teams or firefighters about how to deal with PWDs during crises are important." (M23).

-Strategies for improving the attitude of PWDs about COVID-19: Most participants believed that strengthening collaborations between organizations responsible for providing services to PWDs is the primary strategy to improve their vision by creating a sense of trust, transparency, responsibility, and accountability. Identifying the duties of each organization, better planning for providing services to PWDs, especially regarding how to continue assisting in the COVID-19 crisis, organizing preparation and distribution of medical equipment as well as PPE needed by PWDs, and paying more attention to the activities of NGOs and associations were among the strategies that, according to the participants, can strengthen the government's governance. A few participants also noted the implementation of the Disability Act in the country as a strategy that can motivate them.

"All organizations should work together, such as government offices and municipalities, because we have the right to physical exercise. We are getting older, but there is no one to train us, as there is no gym for PWDs." (M4)

-Strategies for improving the practice of PWDs on COVID-19: Many participants suggested livelihood support packages, either financial or non-financial, as facilitators of observing public health recommendations or even health insurance packages to cover rehabilitation services. Another proposal made by some participants was to continue emphasizing public health protocols and health recommendations by the relevant organizations. Punishments that are even more serious should be considered for violation of these protocols. Considering the vital role of community participation, especially NGOs, in mobilizing resources, providing PPE, and increasing communications, some participants emphasized facilitating their activities and closer relationships with responsible organizations to implement public health protocols better. Few participants also noted creating job opportunities tailored to the current situation for PWDs.

"During the national lockdown, punishments were more serious. There should be punishments for those who violate protocols. We need at least three weeks of lockdown. Besides, the government should support the poor" (M1).

Discussion

The findings indicated that PWDs have a desirable knowledge regarding the COVID-19. Several international [18-29] and national studies [30, 31] reported a desirable level of awareness concerning COVID-19 among the populations. In a study conducted in Germany, Ziprich et al. reported high levels of awareness among patients with Parkinson's disease [32]. Applying different tools for measuring awareness cannot be compared with the present study's findings. However, previous studies have shown several effective interventions performed in different settings to increase communities' awareness [26, 28, 33-35]. Increasing society's awareness has been considered a highly effective policy to fight COVID-19 in Iran, like many other countries [31].

Meanwhile, the importance of tailoring the content and choosing the right communication channels shouldn't be ignored. As shown in the qualitative phase, not using content tailored based on the PWD's needs and inappropriate communication channels were identified as the main obstacles to increase the awareness of PWDs. Several studies have emphasized using educational content tailored to the needs of the target population to increase awareness of health literacy during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for vulnerable groups [23, 24, 29, 30].

According to the findings, socio-economic status was directly associated with PWD's awareness of COVID-19, which was also emphasized in the qualitative phase. This finding can be attributed to higher socio-economic status increases provide opportunities that increase individuals' awareness. This finding is consistent with several studies conducted in different settings [18, 28, 30]. Therefore, it is recommended that policy-makers prioritize programs to improve the livelihood status of PWDs through better education and job opportunities. Investing in eradicating poverty and proper education, especially for disadvantaged populations, has been a constant recommendation to countries to achieve Sustainable Development Goals.

The findings also revealed that the positive attitudes of PWDs about COVID-19 in Iran are not as strong/positive as awareness. Some studies conducted in Iran also reported a soft attitude toward COVID-19 prevention [30]. Some international studies also reported weak attitudes [20]. Some organizations' poor performance responsible for controlling the pandemic and dissatisfaction with their performance has caused negative attitudes in PWDs. Other studies in the Philippines [22] and Nigeria [26] also reported the poor performance of health systems on people's attitudes toward COVID-19. However, the desirable performance of governmental institutions in Vietnam resulted in people's positive attitudes toward COVID-19 [28]. In Iran, what has caused negative attitudes towards COVID-19 is related to the governance at the national level, particularly in the health sector, to provide rehabilitation services. Since promoting preventive behaviors toward COVID-19 would require promoting knowledge and efficacy beliefs among vulnerable people [36-39], we recommend that a particular emphasis be placed on the dynamic health communication process to improve attitude and preventive behavior efficacy among PWDs.

The most important reasons for distrust in governmental organizations are the lack of up-to-date or incorrect statistics, lack of transparency, low accountability, and inadequate inter-sectoral collaboration. Since good governance is crucial for managing crises, policy-makers should prioritize establishing appropriate communication and timely provision of information to increase the sense of trust and hope in society. Several studies mentioned the high impact of government trust on attitudes toward COVID-19 [18, 19, 23, 25]. Another reason for negative attitudes among PWDs was not fulfilling promises, especially on implementing the Comprehensive Disability Welfare Act enacted in 2003 and General Health Policies. Failure to fully enforce the laws or their partial implementation is a common issue in Iran, which is too stressed by previously conducted studies [33]. In addition to these factors, the sense of being ignored or marginalized and not providing necessary facilities were other underlying factors that caused the PWDs to have a more negative attitude. These factors are also mentioned in studies conducted in this field [29, 34, 35]. Thus, more programs and interventions are needed to eliminate discrimination and increase justice, targeting disadvantaged groups.

Concerning the practice of PWD about COVID-19, findings indicated most PWDs follow public health protocols. Previously conducted studies in Iran [30, 31] and other countries [20, 22-29] have reported an adequate practice level. A study on Parkinson's disease reported good adherence to public health protocols [32]. It seems that community participation is the main factor for adherence to these protocols. However, levels of participation were different. The lowest participation level was educating and information at the community scale using various human and social networks.

Although these pieces of training were not specially designed for PWDs, their extensive scope could increase the awareness of PWDs, resulting in improved practice [40]. Although some studies reported that, for COVID-19, patients' training was not associated with improved attitudes and practice [26], several studies reported a significant association [20, 22, 24, 25, 28, 32]. A part of this participation was to assist and cooperate with grassroots groups and organizations in training, informing, mobilizing resources, providing services, and even collecting data and tracking patients. Public participation has a vital role in service provision and providing resources during the pandemic [41]. Considering the government's limited capacity to provide health services and the country's limited fiscal space, it seems that developing programs and interventions to increase community participation in the field of rehabilitative services is necessary.

Despite having an adequate level of practice, it seems that it had a low status compared to the knowledge, somehow due to inadequate, insufficient training. However, it appears that the lack of financial resources or even physical restrictions to purchase the necessary equipment for cleaning and disinfection are the main reasons for non-adherence to public health protocols. This issue indicates the necessity of providing livelihood packages, both financial and non-financial, and programs for the employment of PWDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies also recommended that the government or NGOs pay greater attention to providing PPEs [20, 23].

The findings also showed that the government's educational contents, as a response to the COVID-19 outbreak, had the highest role in increasing the knowledge of PWDs. Several studies emphasized the continuation of training regarding COVID-19 and providing appropriate information to increase society's health literacy. Training should be supplied through main communication channels or identifying prominent influencers, resulting in an interactive and constructive relationship [18, 19, 22, 23, 26-29, 32]. Increased awareness and knowledge are the main facilitators of the satisfactory practice of PWDs. As mentioned earlier, training society is an effective way to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran.

Another facilitator that significantly contributed to the high level of KAP among PWDs was community participation in different dimensions. There is a large body of evidence regarding the impact of community participation in health programs' success, including those related to COVID-19. The next important facilitator was the high level of education and economic status of the PWDs and their families. Both of these factors are social determinants of health, which several studies mentioned their role in promoting health. Previous works mentioned improving the status of these factors to promote societies' health, particularly for vulnerable groups [20, 23]. The same can be true for COVID-19.

Regarding the obstacles to promoting the KAP of PWDs, the most critical barrier is the system's poor governance in service provision. Refraining from implementing the law and regulations, the lack of transparency and accountability, inadequate intersectoral collaboration among institutions engaged in providing services to PWDs, and poor monitoring of distributing services were identified as the main reasons for weak governance in service provision PWDs. The issue of poor governance is also reported by previous studies [42]. Besides directing activities efficiently in normal circumstances, good governance also plays a significant role in crises. Some countries' experience in successful control of the pandemic also indicates the significant role of good governance. Another obstacle was the poor performance of organizations and institutions involved in providing services to PWDs, which has resulted in the sense of dissatisfaction, pessimism, and hopelessness among PWDs. However, one of the government's duties during a crisis is to protect the people, particularly vulnerable groups. Identifying these facilitators and obstacles can provide useful information for policy-makers to implement corrective and supplementary programs to improve the current situation.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first mixed-method study done in Iran to examine the KAP towards COVID-19 among PWDs. We hope that the study will facilitate effective policy implementation to enable PWDs to control the disease. However, the limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The questionnaires were completed by PWDs. On the issues threatening self-reporting studies, reporting bias needs to be improved using administrative data in future studies. We also conducted online interviews, which may have prevented the creation of a conducive atmosphere for participants to involve actively. Further investigations with vigor methodology are recommended to identify the health need of PWDs during a crisis.

Conclusion

Three factors contributed to the desired level of KAP of PWDs about COVID-19, including measures taken since the onset of the outbreak to prepare various educational contents and their distribution, community participation in mobilizing resources, and empowerment of the PWDs and their family. However, since the average KAP of PWDs in almost half of the country's provinces was lower than the national score, there seem to be obstacles to increasing the KAP of PWDs. Based on the findings, the essential barrier is poor governance of rehabilitation services, which caused ignoring the specific needs of PWDs in policies and planning, inequitable distribution of services, which resulted in inappropriate service provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, it can be argued that despite attempts to provide services to PWDs during the COVID-19 pandemic and the necessity of revising the distribution of services, additional interventions are still needed to increase the KAP of PWDs.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the participants who took part in the study.

Ethical Permissions: The approval for this study was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (approved No: IR.USWR.REC.1399.032).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sajadi H.S. (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (35%); Shirazikhah M. (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Nazari M. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%); Sajadi F.S. (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/

Statistical Analyst (10%); Setareh Forouzan A. (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%); Jorjoran Shushtari Z. (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%)

Funding/Support: This study is done with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Grant no: 2466).

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has significantly affected people's lives [1], particularly those who were vulnerable [2]. Persons With Disabilities (PWDs) are among vulnerable groups due to different factors such as; lack of access to resources, social isolation, their dependence on others for care and support [3]. During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, PWDs are at greater risk of dying due to preventable factors and the inability to seek help and access health services. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has spotlighted another systemic vulnerability for PWDs: limited access to health information [4]. Poor access to information among PWDs causes limitations in complying with public health protocols [5]. Thus, it is strongly recommended that COVID-19 risk reduction strategies include PWDs to avoid discrimination and necessitate covering PWDs to achieve universal health coverage [6].

The impact of COVID-19 on PWDs was mainly investigated by scholars to highlight the importance of prioritizing these groups and their problems and challenges [7-12]. However, scant evidence is available to guide how to support PWDs during pandemics [13]. Increasing knowledge, improving attitudes, and practice are helpful to increase precautionary behaviors among PDWs [14], particularly will help them to prevent from getting infected with COVID-19. Moreover, PWD's adherence to the control measures is largely affected by their KAP (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices) towards COVID-19 in accordance with KAP theory. Thus, unequal access to health information and announced health instructions for PWDs are fundamental challenges during pandemics [6, 15, 16]. While educational content news and information about COVID-19 are generally designed for the whole society, it's difficult or almost impossible for PWDs to access and utilize them.

To address this challenge, Iran has taken measures to inform PWDs, as part of its plan to respond to COVID-19. For instance, a practical guideline of COVID-19 for PWDs was developed and distributed to inform PWDs towards COVID-19 prevention [17]. It was expected that this guideline provides applicable information and assists PWDs in protecting themselves and improving their adherence to preventive measures.

To our knowledge, there were no data on KAP about COVID-19 in PWDs. Thus, this study aimed to explore the level of KAP in PWD's related to COVID-19 and identify obstacles and facilitators of promoting their KAP.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive-qualitative study was conducted in two phases on PWDs in Iran in 2020.

Quantitative phase

Descriptive-cross sectional phase was carried out on all PWDs in Iran. The sample size was calculated using a confidence interval of 95% and an error of 3%, which yielded a sample size of 1067. Respondents were selected using a convenience sampling technique. According to the estimated population of PWDs in each province, the number of samples for each province was determined. We uploaded the questionnaire to the Porsline website, an online questionnaire system widely used in academic study in Iran. Then, we shared the questionnaire link generated by Porsline to the WhatsApp and Email of all managers of the Campaign to Support PWDs and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in the field of PWDs in all 31 provinces of the country and asked them to select PWDs randomly and invite them to fill in the questionnaire. The link was subsequently forwarded by these contacts to more PWDs to fill in the questionnaire. IP address restriction technology was adopted to ensure users with the same IP address could only complete the questionnaire once. Our inclusion criteria included membership in the Campaign, access to social media, ability to complete an online questionnaire, and willingness to participate in the study.

Data were collected using a self-administered researcher-made online questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of two main sections: (a) demographic characteristics (11 items); and (b) measuring knowledge (6 items), attitude (6 items), and practice (6 items) of the target population, as well as items on access to and applicability of educational materials related to COVID-19 (4 items). Items related to knowledge (e.g., the main symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, fatigue, dry cough, and aches) had three options of "true", "False", "I don't know," while items on attitude (e.g., in my opinion, early diagnosis of COVID-19 can lead to recovery and successful treatment) were scored on a three-point Likert scale, "agree", "disagree", "don't know." Items on practice (e.g., have you been to a crowded place in recent days) and access to educational content also had two options: "Yes", "No". The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by obtaining the opinions of three experts in rehabilitation services. Reliability was evaluated using a pilot study with a sample of 30 subjects and the McDonald's omega coefficient. The value of this coefficient for items related to knowledge, attitude, and practice was 0.86, 0.86, and 0.85, respectively. Each item had a score of 1 to 20. Scores higher than 15 were categorized as "good," between 10 to 15 as "moderate," and less than ten as "weak."

The approval for this study was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. After finalizing the

questionnaire, it was available through the Porsline platform. The questionnaire was available for an entire month (May 9- June 9, 2020), which required seven minutes of overage to be filled.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software. Since data were not normally distributed, two nonparametric tests, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis, were used.

Qualitative phase

This part is intended to identify obstacles and facilitators of promoting the PWDs' KAP using a qualitative approach in July and August 2020. Participants were PWDs who were selected by a purposive sampling method. These participants were different from those who took part in the previous phase. Researchers tried to include people with different experiences and achieve maximum gender, age, education, and socio-economic status. The sampling was stopped upon reaching data saturation, which was 32 interviews. The inclusion criteria included the ability and willingness to participate in the study.

Data were collected using online semi-structured interviews. The interview guide was developed, piloted, and finalized based on the feedback.

The approval for this section of the study was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. The interviews were conducted by a trained interviewer. At the end of the interview, contact means were determined for further communications, if needed. The interviews were all audio-recorded by a Voice Recorder (Sony ICD-UX570), transcribed. Analyzing the interviews was conducted simultaneously with the data collection process. The transcripts were reviewed several times, and then meaning codes were extracted by two researchers independently. Afterward, themes and sub-themes were extracted, and frequent meetings were held to discuss the themes and sub-themes. Discrepancies were resolved via prolonged discussions.

Findings

Quantitative phase

In total, 1067 questionnaires were filled and analyzed. The mean±SD of participants' age was 36.8±15.2, and the duration of being disabled was 24.6±15.0 (Table 1).

The KAP mean±SD scores of PWDs concerning COVID-19 separated by province were provided in Table 2. There was a significant difference between provinces concerning the KAP score (p<0.05). The level of KAP was good for the whole country. There was a significant difference between the mean±SD scores of KAP (p<0.05).

The mean score of knowledge was higher than attitude and practice, while there was no significant difference between attitude and practice scores (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 1) Participant’s demographic characteristics (N=1067)

Table 2) Results of mean±SD of knowledge, attitude, and practices of PWDs concerning COVID-19 (n=1067)

Continue of Table 2) Results of mean±SD of knowledge, attitude, and practices of PWDs concerning COVID-19 (n=1067)

Table 3) Results of the relationship between demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitude, and practices of persons with disabilities concerning COVID- 19 (Mean±SD)

Qualitative phase

In this study, 32 interviews were performed, which on average lasted 38.1 minutes (with a range from 7 to 84 Minutes). The mean age of participants was 43.9±11.3 years. Demographic information of the interviewee is provided in Table 4.

One hundred sixty-one codes were identified, categorized into three themes and nine subthemes (Table 5).

Table 4) Respondent’s demographic characteristics (n=32)

Table 5) Themes and subthemes related to facilitators and barriers of knowledge, attitude, and practices of persons with disabilities concerning COVID- 19

Theme 1: Facilitators of better KAP of PWDs towards COVID-19

-Factors facilitating PWD's knowledge about COVID-19: Almost all respondents mentioned using one or more sources to obtain news, information, and educational content regarding COVID-19. The most important source of obtaining information is social media, according to the interviews. Social networks established in WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram played a leading role in delivering relevant educational content information to PWDs. Respondents also mentioned national broadcasting, especially national TV, as a primary source of information. Very few people also mentioned receiving news and information from international broadcasting. For some participants, several health organizations such as medical universities, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME), or the World Health Organization were the primary educational information sources. Some people noted the developed COVID- 19 self-assessment systems by the MoHME and their subsequent follow-ups as important information sources. A few respondents also mentioned organizations such as the Welfare Organization, the Ministry of Education, and provincial governments as the primary source of information. Interestingly, very few respondents had actively obtained information about the disease even before the official announcement of the COVID-19 news.

"As soon as the pandemic spread in Iran, we created a news channel on WhatsApp to educate PWDs—most of them are heads of households—in this regard. Fortunately, we have many educated people in Bandar Abbas, and we provided them with educational videos and requested to keep themselves updated with the latest shared information. University communities also helped us in this way." (M5)

Respondents also mentioned access to protocols and educational content specifically designed for COVID-19 as facilitators to increase awareness. Besides, protocols are developed for the whole society, both PWDs and other people. In addition to informing others, PWDs, and society's participation in developing educational content has a crucial role in increasing the awareness of PWDs. Since educational content, news, and information about COVID-19 are generally designed for the whole society; it's difficult or almost impossible for PWDs to access them. Hence, PWDs or related associations began to develop content tailored to this target group. In addition to education, these public organizations also began to use appropriate communication channels and broadcasting, primarily for PWDs, which has an essential role in increasing the awareness of PWDs. Another form of public participation to raise awareness of PWDs was the voluntary counseling of some physicians and health workers, who were focused on answering their questions and providing them with the necessary information. The last facilitator was the empowerment of PWDs. Those PWDs from high socio-economic classes had a higher level of awareness about COVID-19, mainly due to their characteristics and better access to educational content.

-Factors that improve attitude PWDs regarding COVID-19: According to participants, the excellent practice of responsible organizations and agencies improved the attitude of PWDs toward COVID-19. Society's active participation in managing the pandemic has also been considered a facilitator. Participants noted that continuous participation of NGOs, donors, and friendly relationships between members of social networks, caused PWDs in small groups to connect and share their fears and experiences to create and maintain more hopeful views. Another facilitator was the sound and respectful behavior of health care providers, which addressed their concerns about inadequate services during the pandemic.

"Ministry of Health, national broadcasting, and Red Crescent Organization appropriately reacted. They informed, educated, and provided care to PWDs, eventuated in satisfaction and positive vision towards them" (M8).

-Facilitating factors for improving the practice of PWDs about COVID-19: Participants mentioned increased awareness as the most important facilitator of observing public health protocols. Community participation was another facilitator mentioned by almost all participants. Community participation can be in the form of providing assistance and support packages, educational and information services (tailored to the PWDs' needs), and monitoring and following up on the status of PWDs. This factor has facilitated taking care of PWDs infected with COVID-19. Besides, it was also useful for mobilizing society to provide supportive packages for the poor.

Another important facilitator is access to personal protective equipment (PPE). Although initially, it was challenging to find PPEs, it gradually became easy as the country expanded its production and distribution network. Meanwhile, affordability is another critical issue that should be considered. PWDs or their families' empowerment was another critical factor for good practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"We were gathering every month in our conference hall, but now everything is online." (M5)

Theme 2: Obstacles of KAP of PWDs towards COVID-19

-Obstacles for increasing knowledge of PWD about COVID-19: Although the level of knowledge of PWDs about COVID-19 was satisfactory, participants mentioned substantial obstacles. While PWDs have tried to develop educational content tailored to their special needs, such contents were not coherent enough to be understandable. Another challenge noted by participants was ignorance or neglect of policy-makers in providing proper and continuous education about COVID- 19 to PWDs. Participants believed that the health authorities were mostly focused on training the whole society or high-risk groups, and there was no plan for PWDs. Even though the elderly were introduced as a high-risk group for COVID-19 infection, sufficient attention is not paid. Low quality of educational content was also a significant challenge noted by participants. False information regarding controlling or preventing the disease may disrupt increasing the awareness of PWDs. Insufficient access to educational programs and content due to not using appropriate messages to PWDs was another obstacle.

"No, it wasn't. They also should provide special training to PWDs through national TV, which is ignored. For example, what protocols should be implemented by a blind person when s/he is out of the home to avoid COVID-19 infection." (M4)

Obstacles to improving attitudes of PWDs about COVID-19: According to participants, the negative view of PWDs about COVID-19 was mostly due to the government's poor performance and responsible organizations in providing services to PWDs. Almost all participants mentioned these organizations' inadequate agility and access to services as the main reasons for their disappointment. Other identified obstacles are mostly related to governance issues. One of these obstacles was the lack of data and information about PWDs in some organizations and lack of trust in the reports, statistics, and information announced by some relevant organizations about the COVID-19 patients in Iran and assistance and care provided to PWDs. Moreover, the lack of transparency in the performance of responsible organizations has intensified the dissatisfactions of PWDs.

Another obstacle was the low accountability of the responsible organizations in addressing society's problems, especially PWDs. Lack of accountability has caused disappointment among PWDs so that they were disappointed with any fundamental change. Also, they mentioned not implementing the Disability Law, which was enacted several years ago, as another reason for their dissatisfaction. While before the outbreak, PWDs considered their demands forgotten in the policies, participants of this study believed the COVID-19 pandemic had intensified this problem. Besides, given the absence of defined guidelines and mechanisms for monitoring rehabilitation equipment, PWDs considered the government unable to manage the pandemic effectively.

Although most participants described community participation as an influential factor in creating a positive view of the future, some participants expressed dissatisfaction with some associations. Some participants' misunderstanding about NGOs and government agencies' defined roles and responsibilities led to their unsound expectations reflected in this study. The last obstacle was discrimination and inequality in providing routine rehabilitation services and services and care related to COVID-19. With a sense of second-class citizenship, most of them always feel a sense of discrimination in providing services to PWDs.

"They didn't send any information to the Welfare Organization about the number of PWDs who have been infected with COVID-19, to provide support packages to those in need, or national broadcasting. But we are not a priority for them." (M10)

-Obstacles to improving the practice of PWDs about COVID-19: The most critical obstacle to implementing public health advice by PWDs was the inaccessibility of PPE. Although it was tried to address this problem by mobilizing society, it was insufficient and could not provide everyone access. Participants mentioned inaccessibility in financial and physical access, so buying PPEs was not affordable for many despite the low price.

"It was both rationed and expensive. Disposable gloves and a small bottle of disinfectants, and there was an alcohol and a mask." (M12)

Difficulties in following public health protocols by PWDs was another significant obstacle noted by participants, particularly for those with severe physical disabilities or intellectual disabilities. The lack of infrastructure for providing remote services was another challenge noted by participants. They believed many services could be provided through online platforms. In this case, there was no need to refer to rehabilitation centers, which are in line with public health protocols. However, few people noted receiving online services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The last obstacle was the poor economic condition and the need to provide living expenses, which led them to go into the community to meet their needs despite recommendations to stay at home. However, some cases had no option except to go to their workplace.

Themes 3: Strategies proposed to increase KAP of PWD about COVID-19

Strategies to increase knowledge of PWD about COVID-19: Many participants emphasized that educational content should be developed based on the target group's needs. However, attention should be paid to the needs of PWDs with a history of COVID-19 infection. According to the PWDs' needs, another effective measure would be developing a mental health package, including promoting or maintaining PWDs' mental health. Increase the knowledge of PWDs and respecting their specific needs were other strategies proposed by participants. In this way, we can increase society's participation in meeting some educational needs of PWDs. Empowering PWDs was another strategy proposed by participants. As it's an effective strategy, it can significantly impact increasing awareness of PWDs. Moreover, they mentioned expanding collaborations and facilitating informing and educating PWDs during crises.

"New crises will emerge, and COVID-19 won't be the last. Therefore, we have to be prepared. A crisis Management Organization is established for this purpose. Enabling PWDs to provide first aid, or training rescue teams or firefighters about how to deal with PWDs during crises are important." (M23).

-Strategies for improving the attitude of PWDs about COVID-19: Most participants believed that strengthening collaborations between organizations responsible for providing services to PWDs is the primary strategy to improve their vision by creating a sense of trust, transparency, responsibility, and accountability. Identifying the duties of each organization, better planning for providing services to PWDs, especially regarding how to continue assisting in the COVID-19 crisis, organizing preparation and distribution of medical equipment as well as PPE needed by PWDs, and paying more attention to the activities of NGOs and associations were among the strategies that, according to the participants, can strengthen the government's governance. A few participants also noted the implementation of the Disability Act in the country as a strategy that can motivate them.

"All organizations should work together, such as government offices and municipalities, because we have the right to physical exercise. We are getting older, but there is no one to train us, as there is no gym for PWDs." (M4)

-Strategies for improving the practice of PWDs on COVID-19: Many participants suggested livelihood support packages, either financial or non-financial, as facilitators of observing public health recommendations or even health insurance packages to cover rehabilitation services. Another proposal made by some participants was to continue emphasizing public health protocols and health recommendations by the relevant organizations. Punishments that are even more serious should be considered for violation of these protocols. Considering the vital role of community participation, especially NGOs, in mobilizing resources, providing PPE, and increasing communications, some participants emphasized facilitating their activities and closer relationships with responsible organizations to implement public health protocols better. Few participants also noted creating job opportunities tailored to the current situation for PWDs.

"During the national lockdown, punishments were more serious. There should be punishments for those who violate protocols. We need at least three weeks of lockdown. Besides, the government should support the poor" (M1).

Discussion

The findings indicated that PWDs have a desirable knowledge regarding the COVID-19. Several international [18-29] and national studies [30, 31] reported a desirable level of awareness concerning COVID-19 among the populations. In a study conducted in Germany, Ziprich et al. reported high levels of awareness among patients with Parkinson's disease [32]. Applying different tools for measuring awareness cannot be compared with the present study's findings. However, previous studies have shown several effective interventions performed in different settings to increase communities' awareness [26, 28, 33-35]. Increasing society's awareness has been considered a highly effective policy to fight COVID-19 in Iran, like many other countries [31].

Meanwhile, the importance of tailoring the content and choosing the right communication channels shouldn't be ignored. As shown in the qualitative phase, not using content tailored based on the PWD's needs and inappropriate communication channels were identified as the main obstacles to increase the awareness of PWDs. Several studies have emphasized using educational content tailored to the needs of the target population to increase awareness of health literacy during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for vulnerable groups [23, 24, 29, 30].

According to the findings, socio-economic status was directly associated with PWD's awareness of COVID-19, which was also emphasized in the qualitative phase. This finding can be attributed to higher socio-economic status increases provide opportunities that increase individuals' awareness. This finding is consistent with several studies conducted in different settings [18, 28, 30]. Therefore, it is recommended that policy-makers prioritize programs to improve the livelihood status of PWDs through better education and job opportunities. Investing in eradicating poverty and proper education, especially for disadvantaged populations, has been a constant recommendation to countries to achieve Sustainable Development Goals.

The findings also revealed that the positive attitudes of PWDs about COVID-19 in Iran are not as strong/positive as awareness. Some studies conducted in Iran also reported a soft attitude toward COVID-19 prevention [30]. Some international studies also reported weak attitudes [20]. Some organizations' poor performance responsible for controlling the pandemic and dissatisfaction with their performance has caused negative attitudes in PWDs. Other studies in the Philippines [22] and Nigeria [26] also reported the poor performance of health systems on people's attitudes toward COVID-19. However, the desirable performance of governmental institutions in Vietnam resulted in people's positive attitudes toward COVID-19 [28]. In Iran, what has caused negative attitudes towards COVID-19 is related to the governance at the national level, particularly in the health sector, to provide rehabilitation services. Since promoting preventive behaviors toward COVID-19 would require promoting knowledge and efficacy beliefs among vulnerable people [36-39], we recommend that a particular emphasis be placed on the dynamic health communication process to improve attitude and preventive behavior efficacy among PWDs.

The most important reasons for distrust in governmental organizations are the lack of up-to-date or incorrect statistics, lack of transparency, low accountability, and inadequate inter-sectoral collaboration. Since good governance is crucial for managing crises, policy-makers should prioritize establishing appropriate communication and timely provision of information to increase the sense of trust and hope in society. Several studies mentioned the high impact of government trust on attitudes toward COVID-19 [18, 19, 23, 25]. Another reason for negative attitudes among PWDs was not fulfilling promises, especially on implementing the Comprehensive Disability Welfare Act enacted in 2003 and General Health Policies. Failure to fully enforce the laws or their partial implementation is a common issue in Iran, which is too stressed by previously conducted studies [33]. In addition to these factors, the sense of being ignored or marginalized and not providing necessary facilities were other underlying factors that caused the PWDs to have a more negative attitude. These factors are also mentioned in studies conducted in this field [29, 34, 35]. Thus, more programs and interventions are needed to eliminate discrimination and increase justice, targeting disadvantaged groups.

Concerning the practice of PWD about COVID-19, findings indicated most PWDs follow public health protocols. Previously conducted studies in Iran [30, 31] and other countries [20, 22-29] have reported an adequate practice level. A study on Parkinson's disease reported good adherence to public health protocols [32]. It seems that community participation is the main factor for adherence to these protocols. However, levels of participation were different. The lowest participation level was educating and information at the community scale using various human and social networks.

Although these pieces of training were not specially designed for PWDs, their extensive scope could increase the awareness of PWDs, resulting in improved practice [40]. Although some studies reported that, for COVID-19, patients' training was not associated with improved attitudes and practice [26], several studies reported a significant association [20, 22, 24, 25, 28, 32]. A part of this participation was to assist and cooperate with grassroots groups and organizations in training, informing, mobilizing resources, providing services, and even collecting data and tracking patients. Public participation has a vital role in service provision and providing resources during the pandemic [41]. Considering the government's limited capacity to provide health services and the country's limited fiscal space, it seems that developing programs and interventions to increase community participation in the field of rehabilitative services is necessary.

Despite having an adequate level of practice, it seems that it had a low status compared to the knowledge, somehow due to inadequate, insufficient training. However, it appears that the lack of financial resources or even physical restrictions to purchase the necessary equipment for cleaning and disinfection are the main reasons for non-adherence to public health protocols. This issue indicates the necessity of providing livelihood packages, both financial and non-financial, and programs for the employment of PWDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies also recommended that the government or NGOs pay greater attention to providing PPEs [20, 23].

The findings also showed that the government's educational contents, as a response to the COVID-19 outbreak, had the highest role in increasing the knowledge of PWDs. Several studies emphasized the continuation of training regarding COVID-19 and providing appropriate information to increase society's health literacy. Training should be supplied through main communication channels or identifying prominent influencers, resulting in an interactive and constructive relationship [18, 19, 22, 23, 26-29, 32]. Increased awareness and knowledge are the main facilitators of the satisfactory practice of PWDs. As mentioned earlier, training society is an effective way to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran.

Another facilitator that significantly contributed to the high level of KAP among PWDs was community participation in different dimensions. There is a large body of evidence regarding the impact of community participation in health programs' success, including those related to COVID-19. The next important facilitator was the high level of education and economic status of the PWDs and their families. Both of these factors are social determinants of health, which several studies mentioned their role in promoting health. Previous works mentioned improving the status of these factors to promote societies' health, particularly for vulnerable groups [20, 23]. The same can be true for COVID-19.

Regarding the obstacles to promoting the KAP of PWDs, the most critical barrier is the system's poor governance in service provision. Refraining from implementing the law and regulations, the lack of transparency and accountability, inadequate intersectoral collaboration among institutions engaged in providing services to PWDs, and poor monitoring of distributing services were identified as the main reasons for weak governance in service provision PWDs. The issue of poor governance is also reported by previous studies [42]. Besides directing activities efficiently in normal circumstances, good governance also plays a significant role in crises. Some countries' experience in successful control of the pandemic also indicates the significant role of good governance. Another obstacle was the poor performance of organizations and institutions involved in providing services to PWDs, which has resulted in the sense of dissatisfaction, pessimism, and hopelessness among PWDs. However, one of the government's duties during a crisis is to protect the people, particularly vulnerable groups. Identifying these facilitators and obstacles can provide useful information for policy-makers to implement corrective and supplementary programs to improve the current situation.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first mixed-method study done in Iran to examine the KAP towards COVID-19 among PWDs. We hope that the study will facilitate effective policy implementation to enable PWDs to control the disease. However, the limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The questionnaires were completed by PWDs. On the issues threatening self-reporting studies, reporting bias needs to be improved using administrative data in future studies. We also conducted online interviews, which may have prevented the creation of a conducive atmosphere for participants to involve actively. Further investigations with vigor methodology are recommended to identify the health need of PWDs during a crisis.

Conclusion

Three factors contributed to the desired level of KAP of PWDs about COVID-19, including measures taken since the onset of the outbreak to prepare various educational contents and their distribution, community participation in mobilizing resources, and empowerment of the PWDs and their family. However, since the average KAP of PWDs in almost half of the country's provinces was lower than the national score, there seem to be obstacles to increasing the KAP of PWDs. Based on the findings, the essential barrier is poor governance of rehabilitation services, which caused ignoring the specific needs of PWDs in policies and planning, inequitable distribution of services, which resulted in inappropriate service provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, it can be argued that despite attempts to provide services to PWDs during the COVID-19 pandemic and the necessity of revising the distribution of services, additional interventions are still needed to increase the KAP of PWDs.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the participants who took part in the study.

Ethical Permissions: The approval for this study was granted by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (approved No: IR.USWR.REC.1399.032).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution: Sajadi H.S. (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (35%); Shirazikhah M. (Second Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (30%); Nazari M. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%); Sajadi F.S. (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/

Statistical Analyst (10%); Setareh Forouzan A. (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%); Jorjoran Shushtari Z. (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%)

Funding/Support: This study is done with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Grant no: 2466).

Keywords:

References

1. Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185-93. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Andrews EE, Ayers KB, Brown KS, Dunn DS, Pilarski CR. Nobody is expendable: Medical rationing and disability justice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2021;76(3):451-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/amp0000709] [PMID]

3. Ton KT, Gaillard JC, Adamson CE, Akgungor C, Ho HT. Expanding the capabilities of Persons with disabilities in disaster risk reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019;34:11-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.11.002]

4. Sabatello M, Landes SD, McDonald KE. Persons with disabilities in COVID-19: Fixing our priorities. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2020;20(7):187-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15265161.2020.1779396] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. Hassiotis A, Ali A, Courtemanche A, Lunsky Y, McIntyre LL, Napolitamo D, et al. In the time of the pandemic: Safeguarding people with developmental disabilities against the impact of coronavirus. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;13(2):63-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/19315864.2020.1756080]

6. Armitage R, Nellums LB. The COVID-19 response must be disability inclusive. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):257. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30076-1]

7. Lebrasseur A, Fortin-Bedard N, Lettre J, Bussieres EL, Best K, Boucher N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on people with physical disabilities: A rapid review. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(1):101014. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101014] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Sakellariou D, Malfitano APS, Rotarou ES. Disability inclusiveness of government responses to COVID-19 in South America: A framework analysis study. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):131. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12939-020-01244-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

9. Neuville E, Sharma N, Raj L. What's on the other side? the impact of covid 19 on organizations serving people with disability across India. Asia Pac J Manag Technol. 2020;1(2):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.46977/apjmt.2020v01i02.001]

10. Turk MA, McDermott S. The COVID-19 pandemic and people with disability. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(3):100944. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100944] [PMID] [PMCID]

11. World health organization. Protecting people with disability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

12. Chiluba BC, Shula H, Simpamba MM, Kapenda C, Moyo G, Phiri PD, et al. Insights on COVID-19 and disability: A review of the consideration of people with disability in communicating the disease profile and interventions. J Prev Rehabil Med. 2020;2(1):76-83. [Link]

13. World health organization. Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2021 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Disability-2020-1. [Link]

14. Nutbeam D, Lloyd JE. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Ann Rev Public Health. 2021;42:159-73. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529] [PMID]

15. Boyle CA, Fox MH, Havercamp SM, Zubler J. The public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic for Persons with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(3):100943. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100943] [PMID] [PMCID]

16. Senjam SS. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people living with visual disability. Indian J ophthalmol. 2020;68(7):1367-70. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1513_20] [PMID] [PMCID]

17. behzisti.ir [Internet]. Tehran: Iran Welfare Organization; 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.behzisti.ir/. [Persian] [Link]

18. Almalki MJ. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: Planning implications for public health pandemics. Res Sq. 2020 Sep:1-18. [Link] [DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-67654/v1]

19. Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sern TJ, Ayub SH, Mohamad E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Plos One. 2020;15(5):e0233668. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0233668] [PMID] [PMCID]

20. Bates BR, Moncayo AL, Costales JA, Herrera-Cespedes CA, Grijalva MJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among ecuadorians during the outbreak: An online cross-sectional survey. J Community Health. 2020 Sep:1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10900-020-00916-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Geldsetzer P. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional online survey. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar:912. [Link] [DOI:10.7326/M20-0912] [PMID] [PMCID]

22. Lau LL, Hung N, Go DJ, Ferma J, Choi M, Dodd W, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the Philippines: A cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):11007. [Link] [DOI:10.7189/jogh.10.011007] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Ma L, Liu H, Tao Z, Jiang N, Wang S, Jiang X. Knowledge, Beliefs/Attitudes, and practices of rural residents in the prevention and control of COVID-19: An online questionnaire survey. Ame J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(6):2357-67. [Link] [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0314] [PMID] [PMCID]

24. Mousa KNAA, Saad MMY, Abdelghafor MTB. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding COVID-19 among Sudan citizens during the pandemic: An online cross-sectional study. Sudan J Med Sci. 2020;15:32-45. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/sjms.v15i5.7176]

25. Qutob N, Awartani F. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) towards COVID-19 among Palestinians during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional survey. Plos One. 2021;16(1):0244925. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0244925] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Reuben RC, Danladi MM, Saleh DA, Ejembi PE. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: an epidemiological survey in north-central Nigeria. J Community Health. 2020 Jul:1-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10900-020-00881-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Rios-Gonzalez CM. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 in paraguayans during the outbreak period: A quick online survey. Revista Salud Publica Del Paraguay. 2020;10(2):17-22. [Spanish] [Link] [DOI:10.18004/rspp.2020.diciembre.17]

28. Van Nhu H, Tuyet-Hanh TT, Van NTA, Linh TNQ, Tien TQ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the vietnamese as key factors in controlling COVID-19. J Community Health. 2020;45(6):1263-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10900-020-00919-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

29. Yue S, Zhang J, Cao M, Chen B. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among urban and rural residents in China: A cross-sectional study. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):286-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10900-020-00877-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Honarvar B, Lankarani KB, Kharmandar A, Shaygani F, Zahedroozgar M, Haghighi MRR, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, risk perceptions, and practices of adults toward COVID-19: A population and field-based study from Iran. Int J Public Health. 2020 Jun:1-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00038-020-01406-2] [PMID] [PMCID]