Volume 13, Issue 2 (2021)

Iran J War Public Health 2021, 13(2): 91-96 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/07/26 | Accepted: 2021/08/25 | Published: 2021/09/28

Received: 2021/07/26 | Accepted: 2021/08/25 | Published: 2021/09/28

How to cite this article

Reisi S, Sadeghi K, Parvizifard A, Behrozi S, Ahmadi S, Ahmadi S. Psychometric Properties of Obsession with COVID-19 Scale in the General Population of Kermanshah, Iran. Iran J War Public Health 2021; 13 (2) :91-96

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-982-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-982-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Student Research Committee, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medical, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

3- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medical, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medical, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

3- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medical, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (701 Views)

Introduction

COVID-19 first appeared in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and its main symptoms include fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath. According to WHO, COVID-19 was introduced as the sixth public health emergency of international concern [1-3]. Proper attention and giving the proper amount of thought to this issue could assist the pandemic. But when thinking about COVID-19 becomes an obsession, it could lead to an inability to complete the daily tasks and a reduction in functions [4, 5]. With the spread of COVID-19, the hygiene protocols have highlighted the role of frequent handwashing, avoiding physical touch, avoiding touching specific surfaces directly, and using detergents or disinfectants. These actions overlap with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms, and committing to these actions affects the appearance of OCD [6]. The obsessive thought content does not suddenly emerge; it appears after external events [7, 8]. Obsessive-compulsive disorder can be identified by repeated and disturbing thoughts or images (obsessive) along with behavioral efforts to neutralize obsessive-compulsive disorder [9].

The epidemic nature of infectious diseases leads to a rise in psychological disorders; however, the features of the COVID-19 pandemic can directly affect obsessive-compulsive disorder and its process, and it is predicted that about 3% of the general population is affected by them [10]. The most dangerous aspects of being diagnosed with COVID-19-related obsessive thoughts are observed in individuals concerned about getting contaminated or damaging others. Furthermore, the individuals who seek reassurance or confirmation of the others by doing excessive research on COVID-19 news are significantly at more risk. Some individuals get rid of COVID-19-related anxiety by repetitive handwashing [11]. The main Obsession with COVID-19 scale was designed in America [4]. This scale is a new measurement that consists of four items. These items were assessed persistently and disturbed thinking about COVID-19. Higher scores predict more intense COVID-19-related obsession [12].

According to the prevalence of COVID-19, utilizing a reliable and valid scale for the accurate assessment of COVID-19 related obsession symptoms during the pandemic seems necessary. Therefore, the current study aimed at determining the psychometric properties of the COVID-19 related obsession scale in the general population of Kermanshah.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out on all people of Kermanshah, Iran, in 2020. After using the convenience sampling method, 405 individuals were selected based on the Morgan sample size table. Inclusion criteria in this study include living in Kermanshah City, Iran, and the ability to read and write. Exclusion criteria in the present study included: invalid questionnaires (incomplete response to the questionnaire).

The measurements utilized include the demographic information questionnaire, Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS), The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), and The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS).

Demographic information questionnaires: This research-made questionnaire included items about the age, gender, marital status, education, being diagnosed with COVID-19 (for the participants and their family/people who had close contact with the participants), history of underlying conditions, and history of substance abuse or smoking.

Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS) [4]: This recently developed scale consists of four items that assess the constant distressing thoughts about COVID-19. The items are scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day) on a 5-point Likert scale and assess the persistent and disturbed thinking about COVID-19 within the last two weeks. Higher scores indicated a more severe obsession with COVID-19. The scores of this scale vary from 0 to 16. The reliability of this scale is 0.74 [12]. Lee has reported the cut-off point to be seven or higher [4]. The correlation coefficient of the American and Pakistani versions of OCS is 0.68, indicating a quite strong correlation [12].

Depression, anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [13]: This scale includes two long (42 items) and short (21 items) versions. In the current study, the short form has been utilized. In the 21-item version, each subscale, including depression, anxiety, and stress, is examined via seven items. All the items are scored between 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much) on a 4-point Likert scale. To measure the score for each subscale, the relevant items are added up and then multiplied by two. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. The total score of this scale ranges from 0 to 126 and from 0 to 42 for each subscale. According to the findings, the test-retest reliability measurements for depression, anxiety, and stress were 0.71, 0.79, and 0.81, respectively [13]. The correlations between this scale and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were 0.81 and 0.74 sequentially [13]. The 21-item form of DASS was validated for the general population of Kermanshah by Sahebi et al., and Cronbach's alpha was also reported for depression (0.77), anxiety (0.79), and stress (0.78) [14]. According to Moradipanah et al., the Cronbach's alpha for depression, anxiety, and stress are 0.94, 0.92, and 0.82 [15].

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) [16]: Being a semi-structured interview, Y-BOCS is utilized for examining the intensity of the current obsessions and compulsions. Unlike the other available questionnaires for assessing this disorder, Y-BOCS is highly sensitive, such that some researchers have mentioned this scale as the gold standard for examining the intensity of OCD symptoms [17]. Y-BOCS consists of two inventories: A Symptom Checklist (SC) and a Severity Scale (SS) [16]. This 10-item scale is scored from 0 to 4 on a 5-point Likert rating system. The final scores range from 0 to 40. Higher scores are indications of the higher severity of the disorder. The internal consistency of the symptom checklist (SC) and the Severity Scale (SS) is 0.97 and 0.95, respectively. Moreover, the split-half reliability was 0.93 for the symptom checklist (SC) and 0.89 for the severity scale (SS). The total test-retest reliability was 0.99 [18].

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. All procedures followed the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The questionnaires were available online regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and the number of the mentioned population for data collection. The participants were given some information about the research at the top of the online form to make an informed decision about their participation in the investigation. Moreover, the participants could take part in the study completely freely. The questionnaires were prepared online using Google Form and sent to Kermanshah groups or pages in WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram social media messages. In addition, in some cases, they were sent via email to individuals from July to October 2020.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 21 software. Descriptive statistics were utilized to examine the frequency indexes, frequency rate, mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum scores of the participants. Cronbach's alpha was measured to examine the reliability (internal consistency) of OCS, and higher rates than 0.70 were considered proper and acceptable [19]. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was applied to determine the convergent validity of OCS with DASS-21 and Y-BOCS. To interpret the correlation coefficient, 0.40 and higher correlations than 0.40 were considered acceptable. The ranges for interpreting correlation coefficients were as follows: 0.81-1=as excellent, 0.61-0.80=very good, 0.41-0.60=good, 0.21-0.40=fair, and 0-0.20=poor [20]. To examine the construct validity via confirmatory factor analysis, Amos 20 was used. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Chi-Square/degree of freedom ratio (χ2/df) was selected as the proper indexes for examining the fitness and appropriateness of the model. Since the size of the Chi-square is sensitive to the sample size, the chi-square/degree of freedom ratio is used for the general evaluation of the model. The size of χ2/df≤2 indicates the properness of the model, and 2˂χ 2/df≤3 indicates that the model is acceptable. 0≤RMSEA≤0.05 is an indication of good fitness, and 0.05˂RMSEA≤0.08 shows that fitness is acceptable. 0.90≤GFI˂0.95 means that there is an acceptable fitness and 0.95≤GFI≤1.0 indicates acceptable fitness. 0.95≤CFI<0.97 shows acceptable fitness, and 0.97≤CFI≤1.0 shows good fitness. 0.90≤AGFI≤1.0 means good fitness, and 0.85≤AGFI˂0.90 means the fitness is acceptable. 0.95≤NFI≤1.0 and 0.90≤NFI˂0.95 indicate good and acceptable fitness, respectively [21]. Finally, 0.90≤IFI≤1.0 shows good and acceptable fitness for IFI [22].

Findings

During the first stage of data collection, 405 individuals completed the forms. Having screened these participants, five of them were excluded. So, the final analyzed data belonged to 400 participants.

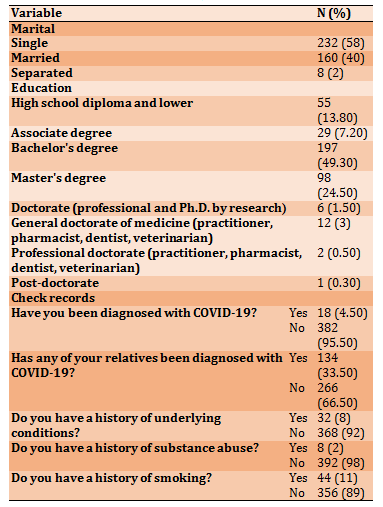

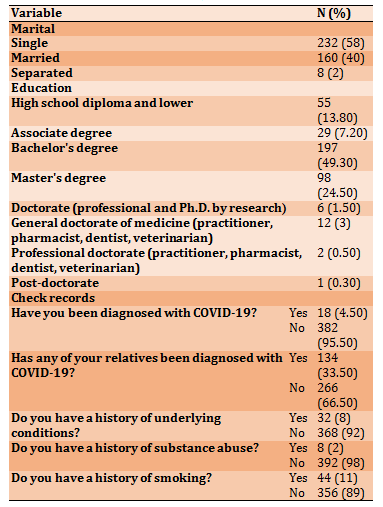

The study population consisted of 94 males (23.5%) and 306 females participants (76.5%), and the mean±SD age of participants was 29.48±9.32 years (Table 1).

Table 1) The information about the demographic characteristics and the background of participants (N=400)

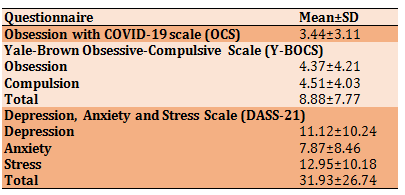

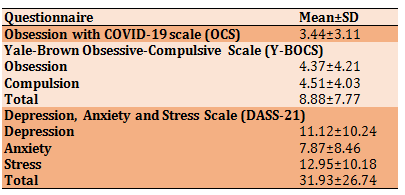

The Mean±SD of indicators for Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS), The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), and The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) were presented in Table 2.

Table 2) Results of mean±SD of questionnaires' variables

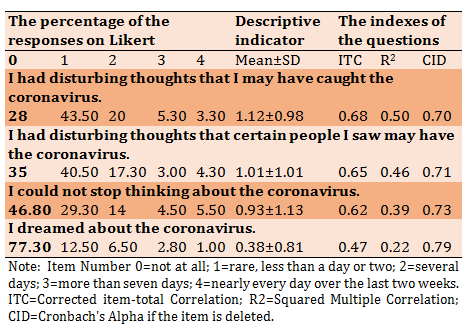

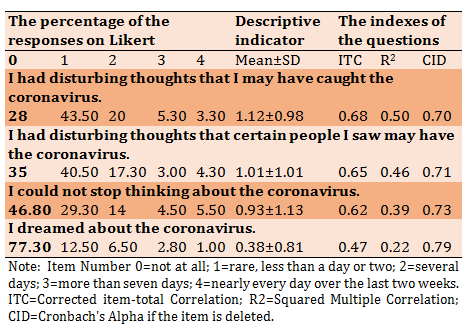

Reliability: The items internal consistency of the OCS questionnaire was provided using Cronbach's alpha, and it was 0.79 (Table 3).

Table 3) The items internal consistency of OCS questionnaire using Cronbach's alpha

Convergent validity: The results of the correlation coefficient test in this study showed that there was a relationship between the OCS scale with Yale-Brown scale (0.46), with obsession subscale was (0.46), and with Compulsion, subscale was (0.41) (p<0.001). Also, there was a significant relationship between OCS scale with DASS-21 scale (0.56), depression subscale was (0.47), anxiety subscale was (0.57), and with stress, subscale was (0.54) (p<0.001).

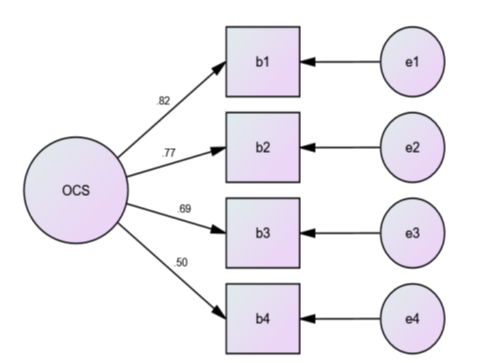

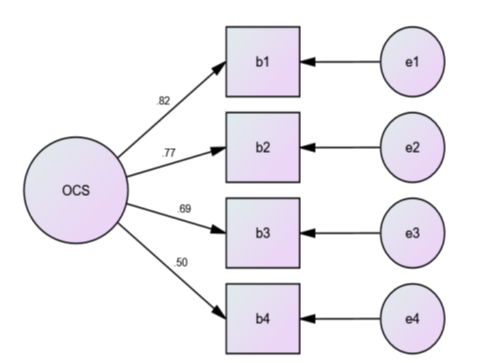

Structural validity: To examine the Structural validity of OCS, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1) The single-factor OCS model

Fitness indicators for the single-factor OCS model obtained (χ2=6.54; df=2; χ2/df=3.27; RMSEA=0.07; IFI=0.99; CFI=0.99; NFI=0.99; GFI=0.99; and AGFI=0.96). Therefore, the measured ratio for χ2/df was quite acceptable. The other calculated indexes, including GFI, AGFI, CFI, IFI, and NFI, indicate the good fitness of the model. Furthermore, the RMSEA ratio showed that the model had acceptable fitness.

Discussion

The current study aims to determine the psychometric properties of obsession with the COVID-19 scale in the general population of Kermanshah. According to the results of the present study, Cronbach's alpha was obtained for this acceptable scale. Furthermore, remove no item omission would lead to a higher Cronbach's alpha for the total scale. The results of this study are in line with the findings of Lee [4] and Ashraf et al. [12].

The results indicated that this scale is positively and significantly correlated with the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales of DASS-21 and Y-BOCS. This correlation indicates the suitable convergent validity of obsession with the COVID-19 scale. There is also a significant positive correlation between the anxiety subscale of DASS-21 and OCS, indicating high convergent validity. The mentioned findings were in line with the findings of Lee [4] and Ashraf et al. [12]. Lee has assessed the validity of obsession with COVID-19 scale using coronavirus anxiety (0.72–0.81), spiritual crisis (0.53–0.64), extreme hopelessness (0.66–0.70), and suicidal ideation (0.45–0.56). Also, the scale's cut-off point is seven and higher [4]. According to the measurements reported by Ashraf et al., the correlations between OCS and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), subscales of social dysfunction and loss of self-confidence were 0.18, 0.19, and 0.13, respectively [12]. Therefore, the OCS seems to be strongly valid.

Moreover, according to the current study, the Convergent Validity of this scale was confirmed and considered suitable for the general population of Kermanshah. Also, the results of this study showed that the single-factor model of this scale had been approved in Iran. These results were in line with results [4, 12].

Considering the situational factors and the specific psychiatric consequences that may emerge or deteriorate following a catastrophe. The pressure caused by obsessive-compulsive disorder is concerning. Even before the global spread of COVID-19, the prevalence of OCD in a lifetime was 2 to 3%. Of all the symptoms, the obsession with contamination and the compulsive handwashing were two of the most common symptoms. Moreover, even though these illnesses are quite effectively cured via medication and psychotherapy, they tend to recur due to being exposed to the stress caused by external or environmental triggers [23]. The recurrence of the symptoms may not happen immediately and take days to months to appear. Common factors, including increased handwashing, the emphasis on observing and following the hygiene guidelines, hypervigilance to contamination, constant searching using cyberspace, ruminative thoughts, and hoarding health supplies and antiseptics during the COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic, could lead to deterioration of symptoms in individuals who were already suffering from OCD symptoms [24]. Washing hands for a long time or using strong antiseptics do not decrease the risk of being infected by COVID-19. Handwashing effectively responds to being exposed to possible external contaminants (for example, when the individual has been outside the home). But in response to anxiety, fear from possible contamination, or mental contamination, handwashing is not an effective action to take [11]. According to what was mentioned above, this short-scale could be suitably utilized for screening the individuals and the related therapeutic diagnoses [25].

Since the questionnaires were completed online, the authors couldn't examine the participants in terms of medical and psychological history. Since all people of Kermanshah were included in the statistical population, some of them may not have been able to read and write; so, the inaccessibility of some individuals (especially in deprived and damage-prone areas) to the internet was a limitation. However, regarding the pandemic and its infectious nature, applying the online Google form was a suitable and safe way to prevent infection. It is suggested that future researchers use this suitable short scale to diagnose the COVID-19 related OCD symptoms and to examine its psychometric properties on patients with COVID-19 or other infectious diseases. Furthermore, it is suggested that the national media present the required education in observing the hygiene guidelines properly, keeping the social distance, wearing masks and gloves, using antiseptics, correct hand washing, and the effective management of the COVID-19 related thoughts to all people. Since the present study was conducted on the general population, the scatter of scores was high. Therefore, it is suggested that in future studies, this scale be studied in specific populations.

Conclusion

The single-factor model of the obsession with the COVID-19 scale has been confirmed in the general population of Kermanshah.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences and the individuals who participated in the present investigation.

Ethical Permissions: This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (IR.KUMS.REC.1399.595).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Reisi S. (First Author), Original Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (20%); Sadeghi Kh. (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (15%); Parvizifard A. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (15%); Behrozi S. (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Ahmadi S.M. (Fifth), Methodologist/Original or Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Ahmadi S.M. (Sixth), Methodologist/Original or Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was financially supported by the vice chancellor for research and technology of Kermanshah University of Medical sciences. This article is taken from the approved plan with code "990593" in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

COVID-19 first appeared in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and its main symptoms include fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath. According to WHO, COVID-19 was introduced as the sixth public health emergency of international concern [1-3]. Proper attention and giving the proper amount of thought to this issue could assist the pandemic. But when thinking about COVID-19 becomes an obsession, it could lead to an inability to complete the daily tasks and a reduction in functions [4, 5]. With the spread of COVID-19, the hygiene protocols have highlighted the role of frequent handwashing, avoiding physical touch, avoiding touching specific surfaces directly, and using detergents or disinfectants. These actions overlap with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms, and committing to these actions affects the appearance of OCD [6]. The obsessive thought content does not suddenly emerge; it appears after external events [7, 8]. Obsessive-compulsive disorder can be identified by repeated and disturbing thoughts or images (obsessive) along with behavioral efforts to neutralize obsessive-compulsive disorder [9].

The epidemic nature of infectious diseases leads to a rise in psychological disorders; however, the features of the COVID-19 pandemic can directly affect obsessive-compulsive disorder and its process, and it is predicted that about 3% of the general population is affected by them [10]. The most dangerous aspects of being diagnosed with COVID-19-related obsessive thoughts are observed in individuals concerned about getting contaminated or damaging others. Furthermore, the individuals who seek reassurance or confirmation of the others by doing excessive research on COVID-19 news are significantly at more risk. Some individuals get rid of COVID-19-related anxiety by repetitive handwashing [11]. The main Obsession with COVID-19 scale was designed in America [4]. This scale is a new measurement that consists of four items. These items were assessed persistently and disturbed thinking about COVID-19. Higher scores predict more intense COVID-19-related obsession [12].

According to the prevalence of COVID-19, utilizing a reliable and valid scale for the accurate assessment of COVID-19 related obsession symptoms during the pandemic seems necessary. Therefore, the current study aimed at determining the psychometric properties of the COVID-19 related obsession scale in the general population of Kermanshah.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out on all people of Kermanshah, Iran, in 2020. After using the convenience sampling method, 405 individuals were selected based on the Morgan sample size table. Inclusion criteria in this study include living in Kermanshah City, Iran, and the ability to read and write. Exclusion criteria in the present study included: invalid questionnaires (incomplete response to the questionnaire).

The measurements utilized include the demographic information questionnaire, Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS), The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), and The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS).

Demographic information questionnaires: This research-made questionnaire included items about the age, gender, marital status, education, being diagnosed with COVID-19 (for the participants and their family/people who had close contact with the participants), history of underlying conditions, and history of substance abuse or smoking.

Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS) [4]: This recently developed scale consists of four items that assess the constant distressing thoughts about COVID-19. The items are scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day) on a 5-point Likert scale and assess the persistent and disturbed thinking about COVID-19 within the last two weeks. Higher scores indicated a more severe obsession with COVID-19. The scores of this scale vary from 0 to 16. The reliability of this scale is 0.74 [12]. Lee has reported the cut-off point to be seven or higher [4]. The correlation coefficient of the American and Pakistani versions of OCS is 0.68, indicating a quite strong correlation [12].

Depression, anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [13]: This scale includes two long (42 items) and short (21 items) versions. In the current study, the short form has been utilized. In the 21-item version, each subscale, including depression, anxiety, and stress, is examined via seven items. All the items are scored between 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much) on a 4-point Likert scale. To measure the score for each subscale, the relevant items are added up and then multiplied by two. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. The total score of this scale ranges from 0 to 126 and from 0 to 42 for each subscale. According to the findings, the test-retest reliability measurements for depression, anxiety, and stress were 0.71, 0.79, and 0.81, respectively [13]. The correlations between this scale and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were 0.81 and 0.74 sequentially [13]. The 21-item form of DASS was validated for the general population of Kermanshah by Sahebi et al., and Cronbach's alpha was also reported for depression (0.77), anxiety (0.79), and stress (0.78) [14]. According to Moradipanah et al., the Cronbach's alpha for depression, anxiety, and stress are 0.94, 0.92, and 0.82 [15].

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) [16]: Being a semi-structured interview, Y-BOCS is utilized for examining the intensity of the current obsessions and compulsions. Unlike the other available questionnaires for assessing this disorder, Y-BOCS is highly sensitive, such that some researchers have mentioned this scale as the gold standard for examining the intensity of OCD symptoms [17]. Y-BOCS consists of two inventories: A Symptom Checklist (SC) and a Severity Scale (SS) [16]. This 10-item scale is scored from 0 to 4 on a 5-point Likert rating system. The final scores range from 0 to 40. Higher scores are indications of the higher severity of the disorder. The internal consistency of the symptom checklist (SC) and the Severity Scale (SS) is 0.97 and 0.95, respectively. Moreover, the split-half reliability was 0.93 for the symptom checklist (SC) and 0.89 for the severity scale (SS). The total test-retest reliability was 0.99 [18].

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. All procedures followed the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The questionnaires were available online regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and the number of the mentioned population for data collection. The participants were given some information about the research at the top of the online form to make an informed decision about their participation in the investigation. Moreover, the participants could take part in the study completely freely. The questionnaires were prepared online using Google Form and sent to Kermanshah groups or pages in WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram social media messages. In addition, in some cases, they were sent via email to individuals from July to October 2020.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 21 software. Descriptive statistics were utilized to examine the frequency indexes, frequency rate, mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum scores of the participants. Cronbach's alpha was measured to examine the reliability (internal consistency) of OCS, and higher rates than 0.70 were considered proper and acceptable [19]. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was applied to determine the convergent validity of OCS with DASS-21 and Y-BOCS. To interpret the correlation coefficient, 0.40 and higher correlations than 0.40 were considered acceptable. The ranges for interpreting correlation coefficients were as follows: 0.81-1=as excellent, 0.61-0.80=very good, 0.41-0.60=good, 0.21-0.40=fair, and 0-0.20=poor [20]. To examine the construct validity via confirmatory factor analysis, Amos 20 was used. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Chi-Square/degree of freedom ratio (χ2/df) was selected as the proper indexes for examining the fitness and appropriateness of the model. Since the size of the Chi-square is sensitive to the sample size, the chi-square/degree of freedom ratio is used for the general evaluation of the model. The size of χ2/df≤2 indicates the properness of the model, and 2˂χ 2/df≤3 indicates that the model is acceptable. 0≤RMSEA≤0.05 is an indication of good fitness, and 0.05˂RMSEA≤0.08 shows that fitness is acceptable. 0.90≤GFI˂0.95 means that there is an acceptable fitness and 0.95≤GFI≤1.0 indicates acceptable fitness. 0.95≤CFI<0.97 shows acceptable fitness, and 0.97≤CFI≤1.0 shows good fitness. 0.90≤AGFI≤1.0 means good fitness, and 0.85≤AGFI˂0.90 means the fitness is acceptable. 0.95≤NFI≤1.0 and 0.90≤NFI˂0.95 indicate good and acceptable fitness, respectively [21]. Finally, 0.90≤IFI≤1.0 shows good and acceptable fitness for IFI [22].

Findings

During the first stage of data collection, 405 individuals completed the forms. Having screened these participants, five of them were excluded. So, the final analyzed data belonged to 400 participants.

The study population consisted of 94 males (23.5%) and 306 females participants (76.5%), and the mean±SD age of participants was 29.48±9.32 years (Table 1).

Table 1) The information about the demographic characteristics and the background of participants (N=400)

The Mean±SD of indicators for Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS), The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), and The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) were presented in Table 2.

Table 2) Results of mean±SD of questionnaires' variables

Reliability: The items internal consistency of the OCS questionnaire was provided using Cronbach's alpha, and it was 0.79 (Table 3).

Table 3) The items internal consistency of OCS questionnaire using Cronbach's alpha

Convergent validity: The results of the correlation coefficient test in this study showed that there was a relationship between the OCS scale with Yale-Brown scale (0.46), with obsession subscale was (0.46), and with Compulsion, subscale was (0.41) (p<0.001). Also, there was a significant relationship between OCS scale with DASS-21 scale (0.56), depression subscale was (0.47), anxiety subscale was (0.57), and with stress, subscale was (0.54) (p<0.001).

Structural validity: To examine the Structural validity of OCS, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1) The single-factor OCS model

Fitness indicators for the single-factor OCS model obtained (χ2=6.54; df=2; χ2/df=3.27; RMSEA=0.07; IFI=0.99; CFI=0.99; NFI=0.99; GFI=0.99; and AGFI=0.96). Therefore, the measured ratio for χ2/df was quite acceptable. The other calculated indexes, including GFI, AGFI, CFI, IFI, and NFI, indicate the good fitness of the model. Furthermore, the RMSEA ratio showed that the model had acceptable fitness.

Discussion

The current study aims to determine the psychometric properties of obsession with the COVID-19 scale in the general population of Kermanshah. According to the results of the present study, Cronbach's alpha was obtained for this acceptable scale. Furthermore, remove no item omission would lead to a higher Cronbach's alpha for the total scale. The results of this study are in line with the findings of Lee [4] and Ashraf et al. [12].

The results indicated that this scale is positively and significantly correlated with the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales of DASS-21 and Y-BOCS. This correlation indicates the suitable convergent validity of obsession with the COVID-19 scale. There is also a significant positive correlation between the anxiety subscale of DASS-21 and OCS, indicating high convergent validity. The mentioned findings were in line with the findings of Lee [4] and Ashraf et al. [12]. Lee has assessed the validity of obsession with COVID-19 scale using coronavirus anxiety (0.72–0.81), spiritual crisis (0.53–0.64), extreme hopelessness (0.66–0.70), and suicidal ideation (0.45–0.56). Also, the scale's cut-off point is seven and higher [4]. According to the measurements reported by Ashraf et al., the correlations between OCS and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), subscales of social dysfunction and loss of self-confidence were 0.18, 0.19, and 0.13, respectively [12]. Therefore, the OCS seems to be strongly valid.

Moreover, according to the current study, the Convergent Validity of this scale was confirmed and considered suitable for the general population of Kermanshah. Also, the results of this study showed that the single-factor model of this scale had been approved in Iran. These results were in line with results [4, 12].

Considering the situational factors and the specific psychiatric consequences that may emerge or deteriorate following a catastrophe. The pressure caused by obsessive-compulsive disorder is concerning. Even before the global spread of COVID-19, the prevalence of OCD in a lifetime was 2 to 3%. Of all the symptoms, the obsession with contamination and the compulsive handwashing were two of the most common symptoms. Moreover, even though these illnesses are quite effectively cured via medication and psychotherapy, they tend to recur due to being exposed to the stress caused by external or environmental triggers [23]. The recurrence of the symptoms may not happen immediately and take days to months to appear. Common factors, including increased handwashing, the emphasis on observing and following the hygiene guidelines, hypervigilance to contamination, constant searching using cyberspace, ruminative thoughts, and hoarding health supplies and antiseptics during the COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic, could lead to deterioration of symptoms in individuals who were already suffering from OCD symptoms [24]. Washing hands for a long time or using strong antiseptics do not decrease the risk of being infected by COVID-19. Handwashing effectively responds to being exposed to possible external contaminants (for example, when the individual has been outside the home). But in response to anxiety, fear from possible contamination, or mental contamination, handwashing is not an effective action to take [11]. According to what was mentioned above, this short-scale could be suitably utilized for screening the individuals and the related therapeutic diagnoses [25].

Since the questionnaires were completed online, the authors couldn't examine the participants in terms of medical and psychological history. Since all people of Kermanshah were included in the statistical population, some of them may not have been able to read and write; so, the inaccessibility of some individuals (especially in deprived and damage-prone areas) to the internet was a limitation. However, regarding the pandemic and its infectious nature, applying the online Google form was a suitable and safe way to prevent infection. It is suggested that future researchers use this suitable short scale to diagnose the COVID-19 related OCD symptoms and to examine its psychometric properties on patients with COVID-19 or other infectious diseases. Furthermore, it is suggested that the national media present the required education in observing the hygiene guidelines properly, keeping the social distance, wearing masks and gloves, using antiseptics, correct hand washing, and the effective management of the COVID-19 related thoughts to all people. Since the present study was conducted on the general population, the scatter of scores was high. Therefore, it is suggested that in future studies, this scale be studied in specific populations.

Conclusion

The single-factor model of the obsession with the COVID-19 scale has been confirmed in the general population of Kermanshah.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences and the individuals who participated in the present investigation.

Ethical Permissions: This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (IR.KUMS.REC.1399.595).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Reisi S. (First Author), Original Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (20%); Sadeghi Kh. (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (15%); Parvizifard A. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Discussion Writer (15%); Behrozi S. (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer/Discussion Writer (15%); Ahmadi S.M. (Fifth), Methodologist/Original or Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Ahmadi S.M. (Sixth), Methodologist/Original or Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%)

Funding/Support: This research was financially supported by the vice chancellor for research and technology of Kermanshah University of Medical sciences. This article is taken from the approved plan with code "990593" in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Keywords:

COVID-19 [MeSH], Obsession with COVID-19 Scale [MeSH], Psychometrics [MeSH], Validity [MeSH], Reliability [MeSH]

References

1. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20. [] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):929-36. [] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):15-6. [] [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X]

4. Lee SA. How much thinking about COVID-19 is clinically dysfunctional. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:97-8. [] [DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.067] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. Jassi A, Shahriyarmolki K, Taylor T, Peile L, Challacombe F, Clark B, et al. OCD and COVID-19: A new frontier. Cogn Behav Therap. 2020;13:27. [] [DOI:10.1017/S1754470X20000318] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. Fontenelle LF, Miguel EC. The impact of COVID‐19 in the diagnosis and treatment of obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(6):510-1. [] [DOI:10.1002/da.23037] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Rachman S. A cognitive theory of obsessions: Elaborations. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(4):385-401. [] [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10041-9]

8. Rowa K, Purdon C, Summerfeldt LJ, Antony MM. Why are some obsessions more upsetting than others. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(11):1453-65. [] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.003] [PMID]

9. American psychiatric association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Virginia: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [] [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

10. Silva RM, Shavitt RG, Costa DL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43(1):108. [] [DOI:10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1189] [PMID] [PMCID]

11. Shafran R, Coughtrey A, Whittal M. Recognising and addressing the impact of COVID-19 on obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):570-2. [] [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30222-4]

12. Ashraf F, Lee SA, Elizabeth Crunk A. Factorial validity of the Urdu version of the obsession with COVID-19 scale: Preliminary investigation using a university sample in Pakistan. Death Stud. 2020 Jun:1-6. [] [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2020.1779436] [PMID]

13. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335-43. [] [DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U]

14. Sahebi A, Asghari MJ, Salari RS. Validation of depression anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21) for an Iranian population. J Iran Psychol. 2005;4(1):299-313. [Persian] []

15. Moradipanah F, Mohammadi E, Mohammadil AZ. Effect of music on anxiety, stress, and depression levels in patients undergoing coronary angiography. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(3):639-47. [] [DOI:10.26719/2009.15.3.639] [PMID]

16. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, et al. The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: II validity. Archives Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1012-6. [] [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008] [PMID]

17. Steketee G, Frost RO. Measurement of risk-taking in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1994;22(4):287-98. [] [DOI:10.1017/S1352465800013175]

18. Esfahani SR, Motaghipour Y, Kamkari K, Zahiredin A, Janbozorgi M. Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the yale-brown obsessive-compulsive scale (Y-BOCS). Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2012;17(4):297-303. [Persian] []

19. Morgan GA, Leech NL, Gloeckner GW, Barrett KC. SPSS for intermediate statistics: Use and interpretation. Taylor & Francis; 2011. [] [DOI:10.4324/9780203842966]

20. Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Omidvari S. The Iranian version of 12-item short form health survey (SF-12): Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:341. [] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-341] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Muller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online. 2003;8(2):23-74. []

22. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238-46. [] [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238] [PMID]

23. Cordeiro T, Sharma MP, Thennarasu K, Reddy YCJ. Symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive beliefs. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(4):403-8. [] [DOI:10.4103/0253-7176.168579] [PMID] [PMCID]

24. Banerjee D. The other side of COVID-19: Impact on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112966. [] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112966] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;70:102196. [] [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102196] [PMID] [PMCID]