Volume 13, Issue 1 (2021)

Iran J War Public Health 2021, 13(1): 23-29 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/02/13 | Accepted: 2021/05/25 | Published: 2021/07/3

Received: 2021/02/13 | Accepted: 2021/05/25 | Published: 2021/07/3

How to cite this article

Alizadeh A, Afkhami S, Dowran B, Ahmadi Tahoor M, Salimi S. Psychological Distress in One of the Branches of the Iranian Military: The Role of Virtues and Character Strengths. Iran J War Public Health 2021; 13 (1) :23-29

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-959-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-959-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Student Research Committee, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Professional University for Health, Aid and Treatment of YAHYAVI Nezaja, Tehran, Iran

3- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- “Exercise Physiology Research Center institute for Life Style” and “Department of Clinical Psychology”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Postal Code: 1756813119

2- Professional University for Health, Aid and Treatment of YAHYAVI Nezaja, Tehran, Iran

3- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- “Exercise Physiology Research Center institute for Life Style” and “Department of Clinical Psychology”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Postal Code: 1756813119

Full-Text (HTML) (1394 Views)

Introduction

Psychological distress (anxiety, depressive reactions, irritability, declining intellectual capacity, tiredness, sleepiness) is a mental health outcome typified by psycho-physiological and behavioral symptoms that are not specific to a given mental pathology [1]. Military personnel faces unpredictable, difficult, and stressful situations in their day-to-day work, and they must be able to handle situations that occur suddenly and with unknown content. As a result, actions may be affected by a high level of difficulty and unpredictability [2]. Consequences such as impairment of individual and group performance, low accuracy at work, emotional problems, alcohol and drug use, inappropriate violence, lack of cooperation and cooperation with the commander, withdrawal from operational areas, divorce and marital problems, Side effects on moral issues and decision-making in military complexes have been cited as complications of psychological distress [3].

Psychological distress is very common in military personnel. Based on a study, the prevalence of various symptoms based on the general GSI syndrome index of the SCL-90 questionnaire was 35.5% [4]. Difficult situations, life dissatisfaction, health problems, work environment conditions, overwork, constant stress, and victimization [5], Job stress (high psychological demands and low decision-making freedom), and isolation stress (high work pressure with low social support) [6], Witnessing acts of cruelty, fear of physical harm, feelings of insecurity, fear of meaninglessness and contact with prisoners, confrontation with war, low social support, and multiple physical symptoms were associated with psychological distress [7].

Military as a positive institution consists of pathology-free mentally and physically fit soldiers, share positive traits, positive emotions, and positive relationships. Therefore, it is imperative to identify, nurture, and optimize all those positive aspects of a soldier, strengthening him for better operational effectiveness, adjustment, and optimal functioning [8]. According to positive military psychology, the military doctrine has affirmed that Virtues and character strengths can be more suitable predictors for successful military personnel and institution [9, 10]. An individual expresses his or her values through one's character. This has been found to play an important role in leadership, adaptability, and achievement [10, 11]. Therefore, Character strengths are important factors for being resilient applicants to high-risk organizations [12].

A soldier must have the courage and aggression to carry out military operations and cultivate the necessary empathy and compassion for dealing humanely with non-combatants and enemy prisoners. Often, the whole spectrum of moral virtues is called to service within minutes [13]. Virtue ethics as the best way to increase the likelihood of soldiers' moral behavior due to laws or rules of conduct applied from above lack flexibility and less room for personal integrity. In addition, changes in the military environment have led to a shift from traditional tasks to more complex ones, and especially in today's missions, one can expect those appropriate virtues are not just combated [14]. Virtues and character strengths are perhaps one of the most potential areas in which positive psychology establishes the US and European army forces [8]. The military doctrine of the Argentine army explicitly states that the future military leader must have certain character strengths [15].

According to Aristotle, virtue is good behavior and enables a person to have a good and prosperous life [16]. Virtue is a profound characteristic of personality that provides the reasons for action with the right motivation to choose, feel, react appropriately in different situations, and have at least two basic characteristics. First, they tend to influence behavior and specifically show appropriate behavior. Then, they mean universal ("universal attributes"). They are assumed to be well-being components that can be used to summarize the representative's past behavior and predict the agent's future behavior [17]. They are a stable and orderly behavior in a wide range of different objective situations [16] and an important and necessary step in advancing the scientific study of moral excellence [15]. Character strengths are psychological ingredients (processes and mechanisms) that define character virtues [15] and are a specific phenomenon that coexists with goals, interests, and values and can be developed through increased awareness and effort [18]. Positive psychology (virtues and character strengths) argues that psychological pathology and distress occur when people's capacities are neutralized by psychological and socio-cultural factors [19].

Peterson and Seligman listed six virtues and 24 character strengths, included wisdom and knowledge (creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, perspective), courage (authenticity, bravery, persistence, zest), humanity (kindness, love, and social intelligence), Justice ( fairness, leadership, citizenship), temperance (forgiveness, modesty, prudence, self-regulation) and transcendence (appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality) [20]. We have designed this study to address several gaps in virtues and character strengths literature. First, Few studies have been conducted on the virtues and character strengths in the military in Iran. Although, a study to investigate the role of character strengths, emotions, and resilience in predicting job stress in a sample of Iranian military personnel. The results showed that higher flexibility and courage are associated with lower job stress [21]. This study only examined virtues and does not include character strengths in the study. Second, a review of previous studies [9, 11, 18] showed that these studies focused on a small sample of experienced military personnel.

We wanted to investigate virtues and strengths in ordinary military forces and the most important virtues and character strengths in the ordinary military. In addition, we are interested to know what is the difference between these virtues with increasing education and work experience in military personnel. Given the importance of positive psychology and psychological distress in militaries, the question is raised about whether virtues and character strengths are related to psychological distress. Can virtues predict psychological distress? Our research did not find a study that comprehensively examines these virtues in relation to the degree of psychological distress in military personnel. Therefore, this study was aimed to examine the role of virtues and character strengths on psychological distress in military personnel comprehensively.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on military men in Tehran from June 3, 2020, to October 31, 2020. The military personnel of Tehran were selected by available sampling. 384 people were selected by available sampling based on the Cochran sample size formula (In this formula: z=1.96; p=q=0.5; and d (error value) =0.05) [22]. To compensate for possible errors and increase the test power, the sample size was increased by 410 units. Participants include male militaries with more than two years of work experiences and higher education of diploma.

A demographic questionnaire was used such as age, work experience (in years), education, military rank). Virtues Inventory in Action (VIA-120) was used to evaluate the virtues and strengths of military personnel. Seligman and Patterson developed a short form of VIA that included 120 items for every 24 factors or character strength. Items are completed on a 5-point Likert scale from "very much like me" [5] to "very much unlike me" [1] and dimensionally represent each character's strength. It is equivalent to the original English long-form (VIA- 240) in reliability, validity, and factor structure. Validity and comparability of the German VIA-120 were examined and indicated that the VIA 120 short form is comparable regarding the validity and reliability of the original VIA 240-item version indicating its potential to be used in large-scale research studies [23]. The reliability of this scale was evaluated by Namdari et al., which was 0.70. Therefore, the face and content validity of the scale was confirmed. In the study, scale reliability through test-retest 0.62 to 0.86, and Cronbach's alpha for the whole scale was 0.97, and the scale of wisdom was 0.87, courage 0.82, humanity 0.82, justice 0.83, temperance 0.78, and transcendence 0.87 is calculated [24]. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was calculated 0.95 for the whole scale and 0.91 for the Wisdom Scale, 0.88 for courage, 0.85 for humanity, 0.84 for Justice, 0.84 for temperance, and 0.91 for transcendence. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was also used to assess psychological distress with 10-item. Responses were scored on a five-point ordinal scale reflecting how much of over the past month time respondents had experienced ten symptoms, such as "feeling tired out for no good reason" and "sad or depressed". The measure has five response categories ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). The items were summed to generate a total score ranging from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological distress. K10 scale has satisfactory psychometric properties for use to measure non-specific psychological distress in the military population [25]. The Persian version of K10 is valid and reliable for evaluating mental health status among patients with type 2 diabetes [26].

This article is part of a doctoral dissertation approved by Baqiyatallah University of Medical Science. Target individuals were informed about the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw from the study at any point. All questionnaires were kept confidential. First, the necessary permits were obtained from the relevant centers to implement the questionnaires, and then the command of each unit was coordinated. Questionnaires were distributed among the military personnel, and explanations were given on answering and confidentiality of the answers. After completing the answer, questionnaires were collected.

Data were analyzed by SPSS 18 and using statistical methods such as correlation, regression, independent-test, and one-way analysis of variance.

Findings

The mean±SD of the age and work experience (years of work in the organization) of the participants were 36.72±7.02 and 17.35±6.19, respectively. In addition, 70% were married, and 30% had mastered and doctorate degrees. 60% worked in the morning shift, 30% in variable work shifts. Participants had 18% employees and non-military ranks in terms of military rank, approximately 50% lieutenants and captains, and the rest of them were majors and colonel.

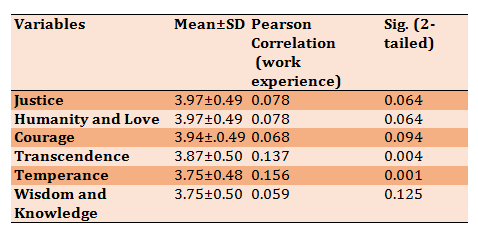

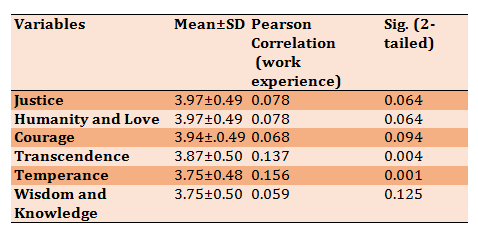

The most important virtues in the Iranian military were Justice, humanity, courage, transcendence, temperance, and wisdom. There was a positive and significant relationship between the two virtues of transcendence and temperance with the work experience of individuals. Transcendence and temperance in the Iranian military had increased with increasing the experience of individuals in the work environment. Other virtues did not show a significant correlation with people's work experience (Table 1).

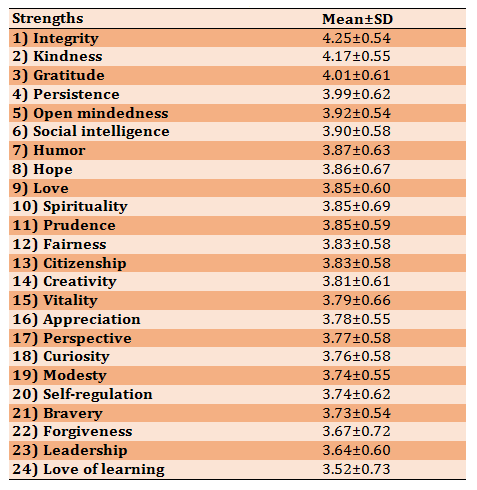

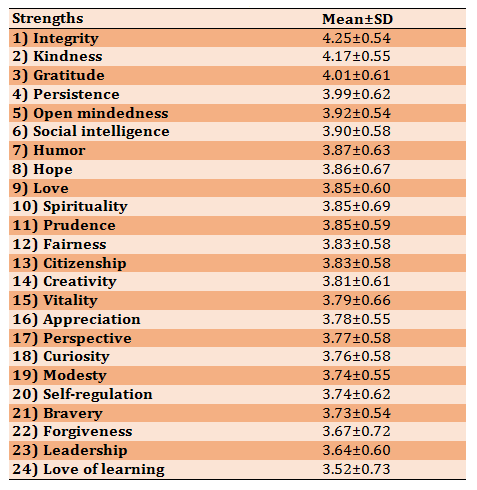

Participants had the highest character strengths: integrity, kindness, gratitude, persistence, Open-mindedness, social intelligence, humor, hope, love, spirituality, and prudence, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1) Mean and Pearson Correlation values between virtues and work experience

Table2) means of character strengths

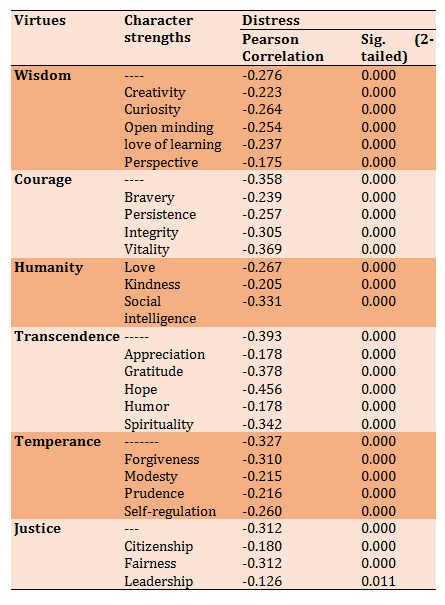

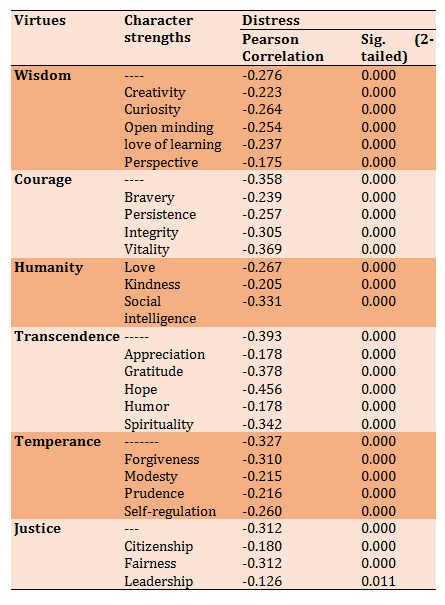

Psychological distress had an inverse and significant relationship with all levels of virtues and character strengths. The virtues and character strengths increased, but the psychological distress decreased (Table 3).

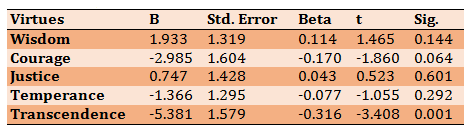

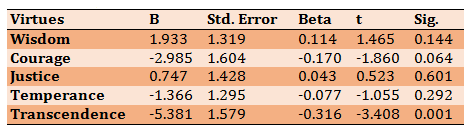

There was a significant difference between the two groups of undergraduate and graduate militaries personnel only in the virtue of wisdom (t=-2.453, df=368, P=.015). In people with higher education, the virtue of wisdom was significantly higher than people with undergraduate. The result of ANOVA showed no significant difference in the six virtues among the groups of military ranks. The results showed that 16% of the variance of psychological distress is explained by this model, which is significant (F=15.95, df=5, p=0.00). Based on this analysis, only the virtue of transcendence could predict psychological distress in military personnel (Table 4).

Table3) Correlations table between virtues and character strengths with psychological distress

Table 4) Regression coefficients' results

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of virtues and character strengths on psychological distress and examine the Iranian military's most important virtues and character strengths. We also wanted to examine the relationship between virtues and character strengths with work experience and education, and military ranks in military personnel.

According to the results of this study, humanity and Justice were two virtues that had a higher average among the six moral virtues of Seligman and Patterson in the Iranian military. There is a lot of overlap and solidarity between the strengths of the character of Justice and humanity [27]. While love is interpersonally created in smaller, individual relationships, Justice is relevant to the individual and the community's optimal interaction [20]. This finding indicates that the Iranian military has strengthened and attached more importance to interpersonal relations than other virtues. In explaining this finding, we can point to the importance of the position of the rights of others in Islam. Human relation requires mercy, empathy, compassion, and kindness, enabling Muslims to strengthen the brotherhood and solidarity among them [28].

Among the character strengths, respectively, Integrity, Kindness, Gratitude, Persistence, Open-mindedness, Social intelligence were six of the most important strengths with which military personnel described themselves. This finding is consistent with the study [29] that mentioned integrity is one of their foremost values in the U.S. Air Force and Army, proclaim [11, 12] team worker, persistence, and love of learning for successful applicants to the Australian Army Special Forces [11]. Previous research has identified 12 character strengths that are the most important for military leaders: leadership, integrity, persistence, bravery, open-mindedness, fairness, citizenship, self-regulation, love of learning, social intelligence, perspective, and creativity [13]. Also, integrity, leadership, good judgment, trustworthiness, and team workers were ranked by the respondents as their chief personal strengths at frequencies significantly above those expected from random allocation [30]. In a study, fairness, honesty, judgment, kindness, and love were the top-five individual signature character strengths on 274 hospital physicians [23].

Next question, what is the difference between the virtues and strengths of personality in Iran's military and previous studies. We reviewed previous studies in this area. In previous studies [9, 18], the average strengths were from about 1.70 to 4.97, but in our study, the average was from 3.52 to 4.25. This difference can be due to the characteristics of the mean mentioned in the introduction. These studies have been conducted on leaders and special officers, and the current study is on a range of Iranian military personnel, regardless of rank, education, or job position. In addition, in the studies mentioned above, the lowest mean was assigned to strengths related to the virtue of transcendence, while in our study, scores of the virtue of transcendence and its character strengths were selected in higher priorities by the Iranian military. In both previous studies, spirituality was the lowest average. In contrast, in our study, gratitude was in the third priority, humor and hope we are in the fourth and fifth, respectively, spirituality in the tenth priority, and admiration of beauty in the sixteenth priority. This finding strengthened the possibility of differences in strengths in the Iranian military under the influence of Iranian society's spiritual and religious culture.

Our findings showed, with the increase of work experience in the military personnel, the virtue of temperance and transcendence has increased. Results of a previous study approved virtues of transcendence increased in old age [31]. Gratitude and appreciation of beauty were given significantly more value in older age than in middle age. Positive associations between spirituality and life satisfaction were found in older but not middle-

aged [31].

According to our findings, virtues differed significantly only in wisdom at the top graduate levels with the undergraduate level. Also, no significant differences were found between the virtues in military ranks. Also, all dimensions of virtues and character strengths were significantly associated with psychological distress. Nevertheless, only the dimension of transcendence had the power to predict psychological distress. In examining the effects of Positive psychology interventions (PPIs), wherein the focus is on eliciting positive feelings, cognitions or behaviors, not only have the potential to improve well-being and reduce distress in populations with clinical disorders. PPIs improved well-being and decreased psychological distress in mood and depressive and psychotic disorders and improving quality of life and well-being in breast cancer patients [32]. In a study, resilience is positively associated with virtues and PTG; by contrast, PTSD scores were negatively but not significantly related to most of these factors [33]. Following the literature, the most strongly related character strengths to life satisfaction were curiosity, gratitude, hope, love, and zest and subjective well-being in total, curiosity, hope. In addition, the possession and applicability of signature character strengths were important in work and private life, but to different degrees. Possessing fairness, honesty, or kindness indicated significant positive relations with subjective well-being, whereas judgment and kindness seemed to interact with reduced personal accomplishment [34] negatively.

According al-Balkhi, when the soul is healthy, all its faculties will be tranquil without any psychological symptoms such as anger, panic, depression, and other similar forms of sickness. Without the control of the rival power of the inner self, negative thought or faulty thinking would lead to emotional pathological habits of anxiety, anger, and sadness and is the main reason behind the psychic disorders of the soul. Therefore, transcendence such as gratitude and spirituality is related to mental health [28], like what was found in our study.

In order to improve future studies, it is suggested that positive psychology interventions be practiced by military personnel and that the results be reviewed on their psychological distress. Also, it is better to examine the relationship between positive psychological variables (virtues and strengths of personality) and hardiness and the degree of tolerance of military conditions in military operational units that serve in specific borders and conditions.

The present study is only a description, and we have not examined the effect of different factors of age, education, and history on the main research variable. In addition, the influence of different regions and cultures of Iranian ethnic groups has not been studied in this study. As their number was very limited, giving a questionnaire to female personnel was another problem in this study. This caused the study to plan for just men personnel. In this study, we did not mention the participants' job characteristics (type of air, land, naval, and defense unit) for security reasons. This study was also conducted in Tehran by the available sampling method. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings of this study.

Conclusion

Strengthening the dimension of transcendence can reduce psychological distress in military personnel. Recognizing the most important Virtues and character strengths in Military Personnel and discovering implications additional ways to promote the virtues, military personnel can improve their performance.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the research participants for their participation in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This article is part of a doctoral dissertation approved with IR.BMSU.REC.1399.341 Ethics Code.

Conflict of Interests: There is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions: Alizadeh A. (First author), Original researcher (35%); Afkhami S.M. (Second author) Introduction author (10%); Dowran B. (Third author) Discussion author (10%); Ahmadi Tahoor M. (Fourth author) Statistical analyst (10%), Salimi S.H. (Fifth author) Assistant researcher (35%).

Funding/Sources: The authors did not receive any resources or funding from any organization.

Psychological distress (anxiety, depressive reactions, irritability, declining intellectual capacity, tiredness, sleepiness) is a mental health outcome typified by psycho-physiological and behavioral symptoms that are not specific to a given mental pathology [1]. Military personnel faces unpredictable, difficult, and stressful situations in their day-to-day work, and they must be able to handle situations that occur suddenly and with unknown content. As a result, actions may be affected by a high level of difficulty and unpredictability [2]. Consequences such as impairment of individual and group performance, low accuracy at work, emotional problems, alcohol and drug use, inappropriate violence, lack of cooperation and cooperation with the commander, withdrawal from operational areas, divorce and marital problems, Side effects on moral issues and decision-making in military complexes have been cited as complications of psychological distress [3].

Psychological distress is very common in military personnel. Based on a study, the prevalence of various symptoms based on the general GSI syndrome index of the SCL-90 questionnaire was 35.5% [4]. Difficult situations, life dissatisfaction, health problems, work environment conditions, overwork, constant stress, and victimization [5], Job stress (high psychological demands and low decision-making freedom), and isolation stress (high work pressure with low social support) [6], Witnessing acts of cruelty, fear of physical harm, feelings of insecurity, fear of meaninglessness and contact with prisoners, confrontation with war, low social support, and multiple physical symptoms were associated with psychological distress [7].

Military as a positive institution consists of pathology-free mentally and physically fit soldiers, share positive traits, positive emotions, and positive relationships. Therefore, it is imperative to identify, nurture, and optimize all those positive aspects of a soldier, strengthening him for better operational effectiveness, adjustment, and optimal functioning [8]. According to positive military psychology, the military doctrine has affirmed that Virtues and character strengths can be more suitable predictors for successful military personnel and institution [9, 10]. An individual expresses his or her values through one's character. This has been found to play an important role in leadership, adaptability, and achievement [10, 11]. Therefore, Character strengths are important factors for being resilient applicants to high-risk organizations [12].

A soldier must have the courage and aggression to carry out military operations and cultivate the necessary empathy and compassion for dealing humanely with non-combatants and enemy prisoners. Often, the whole spectrum of moral virtues is called to service within minutes [13]. Virtue ethics as the best way to increase the likelihood of soldiers' moral behavior due to laws or rules of conduct applied from above lack flexibility and less room for personal integrity. In addition, changes in the military environment have led to a shift from traditional tasks to more complex ones, and especially in today's missions, one can expect those appropriate virtues are not just combated [14]. Virtues and character strengths are perhaps one of the most potential areas in which positive psychology establishes the US and European army forces [8]. The military doctrine of the Argentine army explicitly states that the future military leader must have certain character strengths [15].

According to Aristotle, virtue is good behavior and enables a person to have a good and prosperous life [16]. Virtue is a profound characteristic of personality that provides the reasons for action with the right motivation to choose, feel, react appropriately in different situations, and have at least two basic characteristics. First, they tend to influence behavior and specifically show appropriate behavior. Then, they mean universal ("universal attributes"). They are assumed to be well-being components that can be used to summarize the representative's past behavior and predict the agent's future behavior [17]. They are a stable and orderly behavior in a wide range of different objective situations [16] and an important and necessary step in advancing the scientific study of moral excellence [15]. Character strengths are psychological ingredients (processes and mechanisms) that define character virtues [15] and are a specific phenomenon that coexists with goals, interests, and values and can be developed through increased awareness and effort [18]. Positive psychology (virtues and character strengths) argues that psychological pathology and distress occur when people's capacities are neutralized by psychological and socio-cultural factors [19].

Peterson and Seligman listed six virtues and 24 character strengths, included wisdom and knowledge (creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, perspective), courage (authenticity, bravery, persistence, zest), humanity (kindness, love, and social intelligence), Justice ( fairness, leadership, citizenship), temperance (forgiveness, modesty, prudence, self-regulation) and transcendence (appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality) [20]. We have designed this study to address several gaps in virtues and character strengths literature. First, Few studies have been conducted on the virtues and character strengths in the military in Iran. Although, a study to investigate the role of character strengths, emotions, and resilience in predicting job stress in a sample of Iranian military personnel. The results showed that higher flexibility and courage are associated with lower job stress [21]. This study only examined virtues and does not include character strengths in the study. Second, a review of previous studies [9, 11, 18] showed that these studies focused on a small sample of experienced military personnel.

We wanted to investigate virtues and strengths in ordinary military forces and the most important virtues and character strengths in the ordinary military. In addition, we are interested to know what is the difference between these virtues with increasing education and work experience in military personnel. Given the importance of positive psychology and psychological distress in militaries, the question is raised about whether virtues and character strengths are related to psychological distress. Can virtues predict psychological distress? Our research did not find a study that comprehensively examines these virtues in relation to the degree of psychological distress in military personnel. Therefore, this study was aimed to examine the role of virtues and character strengths on psychological distress in military personnel comprehensively.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on military men in Tehran from June 3, 2020, to October 31, 2020. The military personnel of Tehran were selected by available sampling. 384 people were selected by available sampling based on the Cochran sample size formula (In this formula: z=1.96; p=q=0.5; and d (error value) =0.05) [22]. To compensate for possible errors and increase the test power, the sample size was increased by 410 units. Participants include male militaries with more than two years of work experiences and higher education of diploma.

A demographic questionnaire was used such as age, work experience (in years), education, military rank). Virtues Inventory in Action (VIA-120) was used to evaluate the virtues and strengths of military personnel. Seligman and Patterson developed a short form of VIA that included 120 items for every 24 factors or character strength. Items are completed on a 5-point Likert scale from "very much like me" [5] to "very much unlike me" [1] and dimensionally represent each character's strength. It is equivalent to the original English long-form (VIA- 240) in reliability, validity, and factor structure. Validity and comparability of the German VIA-120 were examined and indicated that the VIA 120 short form is comparable regarding the validity and reliability of the original VIA 240-item version indicating its potential to be used in large-scale research studies [23]. The reliability of this scale was evaluated by Namdari et al., which was 0.70. Therefore, the face and content validity of the scale was confirmed. In the study, scale reliability through test-retest 0.62 to 0.86, and Cronbach's alpha for the whole scale was 0.97, and the scale of wisdom was 0.87, courage 0.82, humanity 0.82, justice 0.83, temperance 0.78, and transcendence 0.87 is calculated [24]. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was calculated 0.95 for the whole scale and 0.91 for the Wisdom Scale, 0.88 for courage, 0.85 for humanity, 0.84 for Justice, 0.84 for temperance, and 0.91 for transcendence. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was also used to assess psychological distress with 10-item. Responses were scored on a five-point ordinal scale reflecting how much of over the past month time respondents had experienced ten symptoms, such as "feeling tired out for no good reason" and "sad or depressed". The measure has five response categories ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). The items were summed to generate a total score ranging from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological distress. K10 scale has satisfactory psychometric properties for use to measure non-specific psychological distress in the military population [25]. The Persian version of K10 is valid and reliable for evaluating mental health status among patients with type 2 diabetes [26].

This article is part of a doctoral dissertation approved by Baqiyatallah University of Medical Science. Target individuals were informed about the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw from the study at any point. All questionnaires were kept confidential. First, the necessary permits were obtained from the relevant centers to implement the questionnaires, and then the command of each unit was coordinated. Questionnaires were distributed among the military personnel, and explanations were given on answering and confidentiality of the answers. After completing the answer, questionnaires were collected.

Data were analyzed by SPSS 18 and using statistical methods such as correlation, regression, independent-test, and one-way analysis of variance.

Findings

The mean±SD of the age and work experience (years of work in the organization) of the participants were 36.72±7.02 and 17.35±6.19, respectively. In addition, 70% were married, and 30% had mastered and doctorate degrees. 60% worked in the morning shift, 30% in variable work shifts. Participants had 18% employees and non-military ranks in terms of military rank, approximately 50% lieutenants and captains, and the rest of them were majors and colonel.

The most important virtues in the Iranian military were Justice, humanity, courage, transcendence, temperance, and wisdom. There was a positive and significant relationship between the two virtues of transcendence and temperance with the work experience of individuals. Transcendence and temperance in the Iranian military had increased with increasing the experience of individuals in the work environment. Other virtues did not show a significant correlation with people's work experience (Table 1).

Participants had the highest character strengths: integrity, kindness, gratitude, persistence, Open-mindedness, social intelligence, humor, hope, love, spirituality, and prudence, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1) Mean and Pearson Correlation values between virtues and work experience

Table2) means of character strengths

Psychological distress had an inverse and significant relationship with all levels of virtues and character strengths. The virtues and character strengths increased, but the psychological distress decreased (Table 3).

There was a significant difference between the two groups of undergraduate and graduate militaries personnel only in the virtue of wisdom (t=-2.453, df=368, P=.015). In people with higher education, the virtue of wisdom was significantly higher than people with undergraduate. The result of ANOVA showed no significant difference in the six virtues among the groups of military ranks. The results showed that 16% of the variance of psychological distress is explained by this model, which is significant (F=15.95, df=5, p=0.00). Based on this analysis, only the virtue of transcendence could predict psychological distress in military personnel (Table 4).

Table3) Correlations table between virtues and character strengths with psychological distress

Table 4) Regression coefficients' results

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of virtues and character strengths on psychological distress and examine the Iranian military's most important virtues and character strengths. We also wanted to examine the relationship between virtues and character strengths with work experience and education, and military ranks in military personnel.

According to the results of this study, humanity and Justice were two virtues that had a higher average among the six moral virtues of Seligman and Patterson in the Iranian military. There is a lot of overlap and solidarity between the strengths of the character of Justice and humanity [27]. While love is interpersonally created in smaller, individual relationships, Justice is relevant to the individual and the community's optimal interaction [20]. This finding indicates that the Iranian military has strengthened and attached more importance to interpersonal relations than other virtues. In explaining this finding, we can point to the importance of the position of the rights of others in Islam. Human relation requires mercy, empathy, compassion, and kindness, enabling Muslims to strengthen the brotherhood and solidarity among them [28].

Among the character strengths, respectively, Integrity, Kindness, Gratitude, Persistence, Open-mindedness, Social intelligence were six of the most important strengths with which military personnel described themselves. This finding is consistent with the study [29] that mentioned integrity is one of their foremost values in the U.S. Air Force and Army, proclaim [11, 12] team worker, persistence, and love of learning for successful applicants to the Australian Army Special Forces [11]. Previous research has identified 12 character strengths that are the most important for military leaders: leadership, integrity, persistence, bravery, open-mindedness, fairness, citizenship, self-regulation, love of learning, social intelligence, perspective, and creativity [13]. Also, integrity, leadership, good judgment, trustworthiness, and team workers were ranked by the respondents as their chief personal strengths at frequencies significantly above those expected from random allocation [30]. In a study, fairness, honesty, judgment, kindness, and love were the top-five individual signature character strengths on 274 hospital physicians [23].

Next question, what is the difference between the virtues and strengths of personality in Iran's military and previous studies. We reviewed previous studies in this area. In previous studies [9, 18], the average strengths were from about 1.70 to 4.97, but in our study, the average was from 3.52 to 4.25. This difference can be due to the characteristics of the mean mentioned in the introduction. These studies have been conducted on leaders and special officers, and the current study is on a range of Iranian military personnel, regardless of rank, education, or job position. In addition, in the studies mentioned above, the lowest mean was assigned to strengths related to the virtue of transcendence, while in our study, scores of the virtue of transcendence and its character strengths were selected in higher priorities by the Iranian military. In both previous studies, spirituality was the lowest average. In contrast, in our study, gratitude was in the third priority, humor and hope we are in the fourth and fifth, respectively, spirituality in the tenth priority, and admiration of beauty in the sixteenth priority. This finding strengthened the possibility of differences in strengths in the Iranian military under the influence of Iranian society's spiritual and religious culture.

Our findings showed, with the increase of work experience in the military personnel, the virtue of temperance and transcendence has increased. Results of a previous study approved virtues of transcendence increased in old age [31]. Gratitude and appreciation of beauty were given significantly more value in older age than in middle age. Positive associations between spirituality and life satisfaction were found in older but not middle-

aged [31].

According to our findings, virtues differed significantly only in wisdom at the top graduate levels with the undergraduate level. Also, no significant differences were found between the virtues in military ranks. Also, all dimensions of virtues and character strengths were significantly associated with psychological distress. Nevertheless, only the dimension of transcendence had the power to predict psychological distress. In examining the effects of Positive psychology interventions (PPIs), wherein the focus is on eliciting positive feelings, cognitions or behaviors, not only have the potential to improve well-being and reduce distress in populations with clinical disorders. PPIs improved well-being and decreased psychological distress in mood and depressive and psychotic disorders and improving quality of life and well-being in breast cancer patients [32]. In a study, resilience is positively associated with virtues and PTG; by contrast, PTSD scores were negatively but not significantly related to most of these factors [33]. Following the literature, the most strongly related character strengths to life satisfaction were curiosity, gratitude, hope, love, and zest and subjective well-being in total, curiosity, hope. In addition, the possession and applicability of signature character strengths were important in work and private life, but to different degrees. Possessing fairness, honesty, or kindness indicated significant positive relations with subjective well-being, whereas judgment and kindness seemed to interact with reduced personal accomplishment [34] negatively.

According al-Balkhi, when the soul is healthy, all its faculties will be tranquil without any psychological symptoms such as anger, panic, depression, and other similar forms of sickness. Without the control of the rival power of the inner self, negative thought or faulty thinking would lead to emotional pathological habits of anxiety, anger, and sadness and is the main reason behind the psychic disorders of the soul. Therefore, transcendence such as gratitude and spirituality is related to mental health [28], like what was found in our study.

In order to improve future studies, it is suggested that positive psychology interventions be practiced by military personnel and that the results be reviewed on their psychological distress. Also, it is better to examine the relationship between positive psychological variables (virtues and strengths of personality) and hardiness and the degree of tolerance of military conditions in military operational units that serve in specific borders and conditions.

The present study is only a description, and we have not examined the effect of different factors of age, education, and history on the main research variable. In addition, the influence of different regions and cultures of Iranian ethnic groups has not been studied in this study. As their number was very limited, giving a questionnaire to female personnel was another problem in this study. This caused the study to plan for just men personnel. In this study, we did not mention the participants' job characteristics (type of air, land, naval, and defense unit) for security reasons. This study was also conducted in Tehran by the available sampling method. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings of this study.

Conclusion

Strengthening the dimension of transcendence can reduce psychological distress in military personnel. Recognizing the most important Virtues and character strengths in Military Personnel and discovering implications additional ways to promote the virtues, military personnel can improve their performance.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the research participants for their participation in the study.

Ethical Permissions: This article is part of a doctoral dissertation approved with IR.BMSU.REC.1399.341 Ethics Code.

Conflict of Interests: There is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions: Alizadeh A. (First author), Original researcher (35%); Afkhami S.M. (Second author) Introduction author (10%); Dowran B. (Third author) Discussion author (10%); Ahmadi Tahoor M. (Fourth author) Statistical analyst (10%), Salimi S.H. (Fifth author) Assistant researcher (35%).

Funding/Sources: The authors did not receive any resources or funding from any organization.

Keywords:

References

1. Marchand A, Drapeau A, Beaulieu-Prévost D. Psychological distress in Canada: The role of employment and reasons of non-employment. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58(6):596-604. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0020764011418404]

2. Solberg OA, Laberg JC, Johnsen BH, Eid J. Predictors of self-efficacy in a Norwegian battalion prior to deployment in an international operation. Mil Psychol. 2005;17(4):299-314. [Link] [DOI:10.1207/s15327876mp1704_4]

3. Skomorovsky A, Sudom KA. Psychological well-being of canadian forces officer candidates: the unique roles of hardiness and personality. Mil Med. 2011;176(4):389-96. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00359]

4. Rahnejat A, Bahamin G, Sajadian SR, Donyavi V. Epidemiological study of psychological disorders in one of the ground units military forces of Islamic Republic of Iran. J Mil Psychol. 2011;2(6):27-36. [Link]

5. Ramos de Souza E, Cecília de Souza MinayoJuliana M, Guimarães e SilvaJ, de Oliveira Pires T. Factors associated with psychological distress among military police in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2012;28(7):1297-311. [Portugueses] [Link]

6. Ferrand JF, Verret C, Trichereau J, Rondier JP, Viance P, Migliani R. Psychosocial risk factors, job characteristics and self-reported health in the Paris Military Hospital Group (PMHG): a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e000999. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000999]

7. Nissen LR, Marott JL, Gyntelberg F, Guldager B. Danish soldiers in Iraq: perceived exposures, psychological distress, and reporting of physical symptoms. Mil Med. 2011;176(10):1138-43. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00094]

8. Singh JK. Psychological strength in military set up: current status and Future direction. Def Life Sci J. 2018;3(4):340-7. [Link] [DOI:10.14429/dlsj.3.13403]

9. Boe BO, Bang H. The big 12: the most important character strengths for military officers. Athens J Soc Sci. 2017;2(2):161-74. [Link] [DOI:10.30958/ajss.4-2-4]

10. Matthews MD, Eid J, Kelly D, Bailey JKS, Peterson C. Character strengths and virtues of developing military leaders: an international comparison. Mil Psychol. 2006;18:57-68. [Link] [DOI:10.1207/s15327876mp1803s_5]

11. Gayton SD, Kehoe EJ. Character strengths and hardiness of Australian army special forces applicants. Mil Med. 2015;180(8):857-62. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00527]

12. Boe O. Building Resilience: The role of character strengths in the selection and education of military leaders. Int J Emerg Ment Health Human Resil. 2015;17(4):714-6. [Link] [DOI:10.4172/1522-4821.1000301]

13. Robinson P. Magnanimity and integrity as military virtues. J Mil Ethic. 2007;6(4):259-69. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15027570701755364]

14. Schulzke M. Rethinking military virtue ethics in an age of unmanned weapons. J Mil Ethic. 2016;15(3):187-204. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/15027570.2016.1257851]

15. Cosentino AC, Solano AC. Character Strengths: A Study of Argentinean Soldiers. Span J Psychol. 2012;15(1):199-215. [Link] [DOI:10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37310]

16. Martin MW. Happiness and virtue in positive psychology. J Theory Soc Behav. 2007;37(1):89-103. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-5914.2007.00322.x]

17. Alzola M. The possibility of virtue. Bus Ethic Q. 2015;22(2):377-404. [Link] [DOI:10.5840/beq201222224]

18. Boea O, Bangb H, Nilsen FA, editors. Experienced military officer's perception of important character strengths. Proced Soc Behav Sci. 2015;190:339-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.008]

19. Aspinwall LG, Tedeschi RG. The value of positive psychology for health psychology: Progress and pitfalls in examining the relation of positive phenomena to health. Annal behav med. 2010;39(1):4-15. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12160-009-9153-0]

20. Ruch W, Proyer RT. Mapping strengths into virtues: the relation of the 24 VIA-strengths to six ubiquitous virtues. Front Psychol. 2015;6:460. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00460]

21. Taghva A, Seyedi Asl ST, Rahnejat AM, Elikaee MM. Resilience, emotions, and character strengths as predictors of job stress in military personnel. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2020;14(2):e86477. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.86477]

22. Boe O, Nilsen FA, Kristianse O, Krogdahl P, Bang H. Measuring important character strengths in norwegian special forces officers. International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, Spain, 3-5 July, 2017. Unknown City: Iated; 2017. [Link] [DOI:10.21125/edulearn.2017.1349]

23. Naing L, Winn T, Rusli B. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofacial Sci. 2006;1:9-14. [Link]

24. Höfer S, Hausler M, Huber A, Strecker C, Renn D, Höge T. Psychometric characteristics of the German values in actioninventory of strengths 120-item short form. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15:597-611. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11482-018-9696-y]

25. Mahavarpoor F, Asadi S, Bakhshayesh A. Development of changes in virtues and character strengths in adulthood with regard to gender differences. Posit Psychol Res. 2019;5(1):71-88. [Persian] [Link]

26. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Zamorski M, Colman I. The psychometric properties of the 10-item kessler psychological distress scale (k10) in canadian military personnel. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196562. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0196562]

27. Ataei J, Shamshirgaran S, Iranparvar M, Safaeian A, Malek A. Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the Kessler psychological distress scale among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Anal Res Clin Med. 2015;3(2):99-106. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/jarcm.2015.015]

28. Park N, Peterson C. Character strengths: Research and practice. J College Character. 2009;10(4). [Link] [DOI:10.2202/1940-1639.1042]

29. Abdullah F. Virtues and character development in islamic ethics and positive psychology. Int J Educ Soc Sci. 2014;1(2):69-77. [Link]

30. Fine S, Goldenberg J, Noam Y. Integrity testing and the prediction of counterproductive behaviours in the military. J Occup Organiz Psychol. 2016;89:198-218. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/joop.12117]

31. Gayton M, Kehoe EJ. Character strengths of junior Australian army officers. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e147-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/milmed/usy251]

32. Margelisch K. Character strengths, their valuing and their association with well-being in middle and older age (an exploratory research study). Abschlussarbeit CAS Posit Psychol. 2017. [Link]

33. Chakhssi F, Kraiss JT, Sommers-Spijkerman M, Bohlmeijer ET. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):211. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1739-2]

34. Duan W, Guo P, Gan P. Relationships among trait resilience, virtues, posttraumatic stress disorder, and post-traumatic growth. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125707. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0125707]

35. Huber A, Strecker C, Hausler M, Kachel T, Höge T, Höfer S. Possession and applicability of signature character strengths: what is essential for well-being, work engagement, and burnout?. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15:415-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11482-018-9699-8]