Volume 17, Issue 3 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(3): 211-216 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.ZBMU.REC.1402.080

History

Received: 2025/05/27 | Accepted: 2025/07/3 | Published: 2025/07/22

Received: 2025/05/27 | Accepted: 2025/07/3 | Published: 2025/07/22

How to cite this article

Maghsoudloomahalli M, Shahdadi H, Naderifar M, Abdollahimohammad A, Podinehmoghadam M. Effects of Home Visit Empowerment Program on Burden and Self-Efficacy of Caregivers of Iran-Iraq War Diabetic Veterans. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (3) :211-216

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1577-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1577-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

M. Maghsoudloomahalli *1, H. Shahdadi2, M. Naderifar1, A. Abdollahimohammad1, M. Podinehmoghadam1

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Zabol University of Medical Science, Zabol, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Zabol University of Medical Science, Zabol, Iran, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Ferdosi Sharghi Street, Zabol, Iran. Postal Code: 9861663335 (zb5950@gmail.com)

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Zabol University of Medical Science, Zabol, Iran, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Ferdosi Sharghi Street, Zabol, Iran. Postal Code: 9861663335 (zb5950@gmail.com)

Full-Text (HTML) (190 Views)

Introduction

Veterans of the Iran-Iraq war experience numerous health challenges that extend to their families [1]. The presence of a chronic illness in a family member significantly impacts family dynamics, relationships, and overall family structure, presenting challenges in adaptation and management [2]. Research highlights the reciprocal influence between chronic patients and their families, where the health of one member affects the well-being of others. Family caregivers play an essential role in healthcare services, contributing significantly to the treatment and management of chronic diseases [3].

Over time, caregivers often experience exhaustion and fatigue due to the physical and mental toll of caregiving. In addition to attending to the veteran’s needs, they must also manage other household responsibilities [4]. The balance between the patient’s demands and the caregiver’s resources and capabilities often leads to caregiving burden, which encompasses physical, emotional, social, and financial strains [5]. Symptoms of caregiving burden include depression, anxiety, feelings of entrapment, and, in severe cases, helpless decision-making or even abandonment of care [6]. Studies indicate that caregivers of veterans frequently experience moderate levels of caregiving burden [7].

Several interventions have been proposed to alleviate caregiving burden, with medical and nursing teams playing a crucial role. These interventions generally focus on empowering caregivers through education, psychological support, and social assistance [8]. In contrast to caregiving burden, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform caregiving tasks effectively. High self-efficacy fosters motivation and belief in one’s caregiving abilities, whereas a decline in self-efficacy can negatively impact both the caregiver’s and the veteran’s health [9, 10]. Engaging caregivers in the treatment process through education can enhance their confidence, improve patient self-care, and increase overall quality of life. While caregivers are not obligated to acquire caregiving knowledge, it is essential for the healthcare team to emphasize their critical role as the veteran’s primary support system [11].

One effective approach to caregiver education is home visits, which tailor educational content to caregivers’ specific needs and available resources [12, 13]. Home visits help deliver healthcare education to individuals with chronic conditions, particularly those living in remote areas with limited access to medical facilities [14]. These programs empower both patients and caregivers, promoting greater independence [15]. The growing recognition of the importance of home visits has led to specialized training programs for nurses in various communities [16]. Proper education and a well-structured home care environment provide continuous support for caregivers and chronic patients while also serving as a cost-effective solution [13].

Beyond the direct consequences of war, veterans experience a higher prevalence of various disorders and diseases compared to the general population. Studies indicate that the prevalence of diabetes among war-injured soldiers in the United States is 25%, while research in Iran has reported a 7.5% prevalence of diabetes among neuropsychiatric veterans [17, 18]. Furthermore, diabetes control among individuals remains suboptimal due to poor adherence to treatment regimens, lifestyle modifications, and disease-related complications [19, 20]. Since more than 95% of diabetes care is managed within the home setting [21], caregivers face significant burdens.

Although numerous studies have examined caregiver burden and self-efficacy, there is a paucity of research specifically focusing on caregivers of Iranian-Iraqi war veterans with diabetes. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effect of a home visit empowerment program on the burden and self-efficacy of caregivers of veterans with diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This single-blind randomized clinical trial was performed on caregivers of veterans diagnosed with diabetes in 2024 at selected healthcare centers in Gorgan, Iran. The sample size was initially estimated at a minimum of 22 participants per group, based on a 95% confidence level, 80% test power, and a 30% probability of attrition [22]. However, to enhance generalizability, 32 participants per group (a total of 64 participants) were recruited. Due to illness-related dropouts, 60 participants completed the study and were included in the final analysis. The sampling method involved purposive selection of health care facilities followed by stratified random sampling of eligible caregivers in the selected facilities.

Caregivers were eligible if they provided full-time care for a veteran with at least a 50% disability and diabetes, were in good health at the time of the study, had at least a fifth-grade education, were not simultaneously caring for another patient, and had not experienced a stressful event in the past six months. Participants were excluded if they withdrew from the study, experienced the death of the caregiver or veteran, developed an acute illness, required hospitalization during the study, encountered a stressful event during the study, or missed two consecutive home visit sessions [4, 23].

Demographic data were collected using a veteran demographic questionnaire, which included details, such as age, gender, economic status, duration of illness, and percentage of disability. Additionally, caregiver demographic information was gathered, covering age, gender, duration of care, caregiver-to-veteran relationship, and education level.

To assess caregiver self-efficacy, Sherer’s Self-Efficacy Questionnaire was used. This 17-item scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items 1, 3, 8, 9, 13, and 15 are reverse-scored. The total possible score ranges from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. Sherer reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 for the general self-efficacy scale. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire have been confirmed in multiple studies conducted in Iran [24, 25].

To measure caregiving burden, the Caregiver Burden Inventory by Novak and Guest, developed in 1989, was used. This 24-item questionnaire is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always), with a total score ranging from 24 to 120. Higher scores indicate a greater caregiving burden [26]. The validity of this questionnaire was confirmed by Abbasi et al. using content and face validity, and its reliability was established with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.69 to 0.87 for subscales and 0.80 for the total questionnaire [11]. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the questionnaire have also been confirmed in various studies in Iran [26, 27].

A list of veterans who met the inclusion criteria was first compiled. Eligible veterans were defined as those with a disability rating of 50% or higher and a confirmed diagnosis of diabetes. Using this list, their caregivers were identified and numbered. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group, with the first randomly selected caregiver placed in the intervention group and the next in the control group. This alternation continued until all participants were assigned, ensuring equal distribution across groups. After obtaining written informed consent, the intervention was initiated. Ethical principles were fully observed in this research. The research objectives were explained to the participants, who were informed about the study process. The confidentiality of participants’ identities and research data was maintained. Additionally, participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

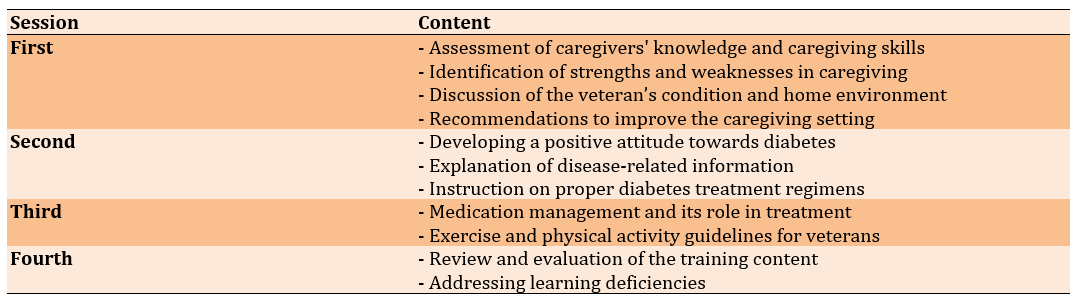

A diabetes education program was developed using relevant sources and under the guidance of diabetes experts and faculty members. After incorporating expert feedback, the program was validated. The intervention consisted of four face-to-face training sessions, each lasting 40 to 60 minutes, conducted in veterans’ homes over a four-week period. Sessions were scheduled weekly, and prior coordination was ensured with caregivers.

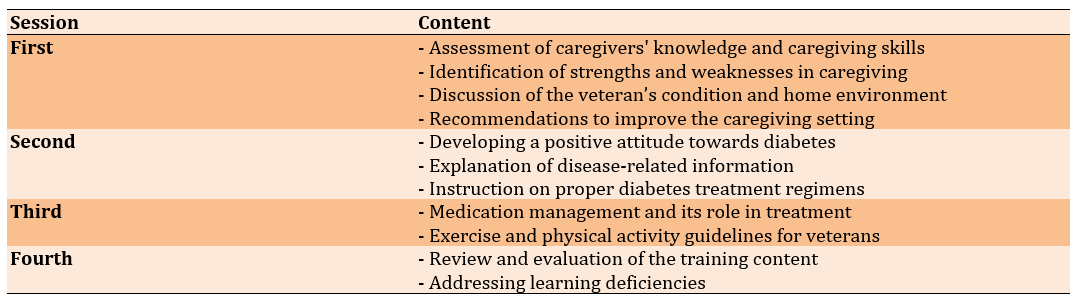

The control group received only routine training through an educational pamphlet. The intervention period lasted three months, during which caregivers in the intervention group received follow-up phone calls to address any training-related questions. Both groups were monitored for compliance with exclusion criteria [28]. At the end of the study, the educational content provided to the intervention group was also given to the control group in booklet form as an appreciation for their participation (Table 1).

Table 1. Home visit empowerment program sessions and content list

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 22 using the Chi-square test, independent t-test, and Fisher’s exact test to compare the two groups.

Findings

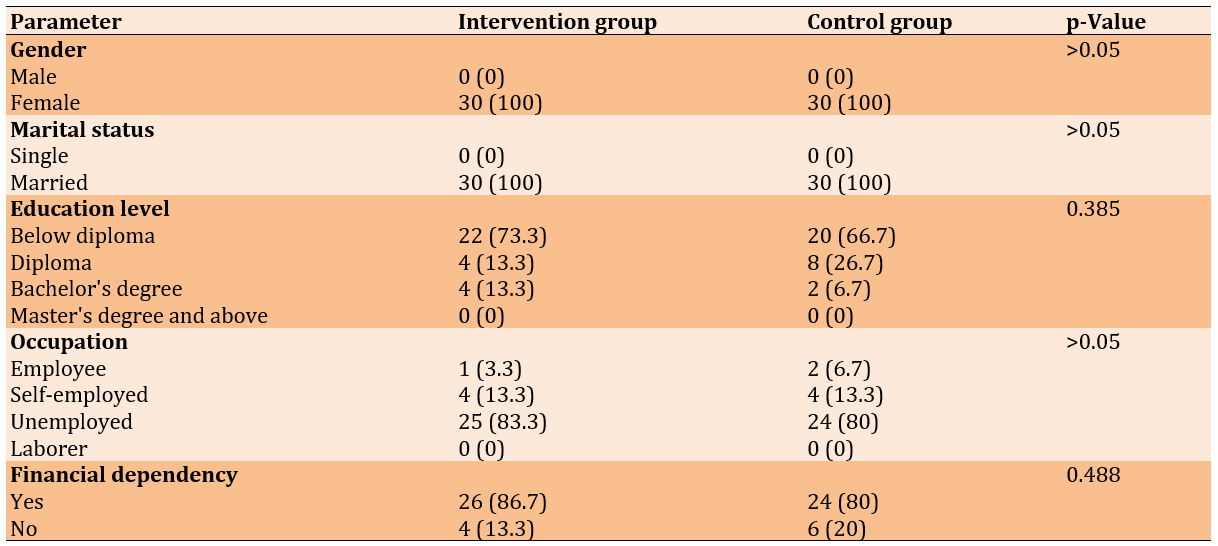

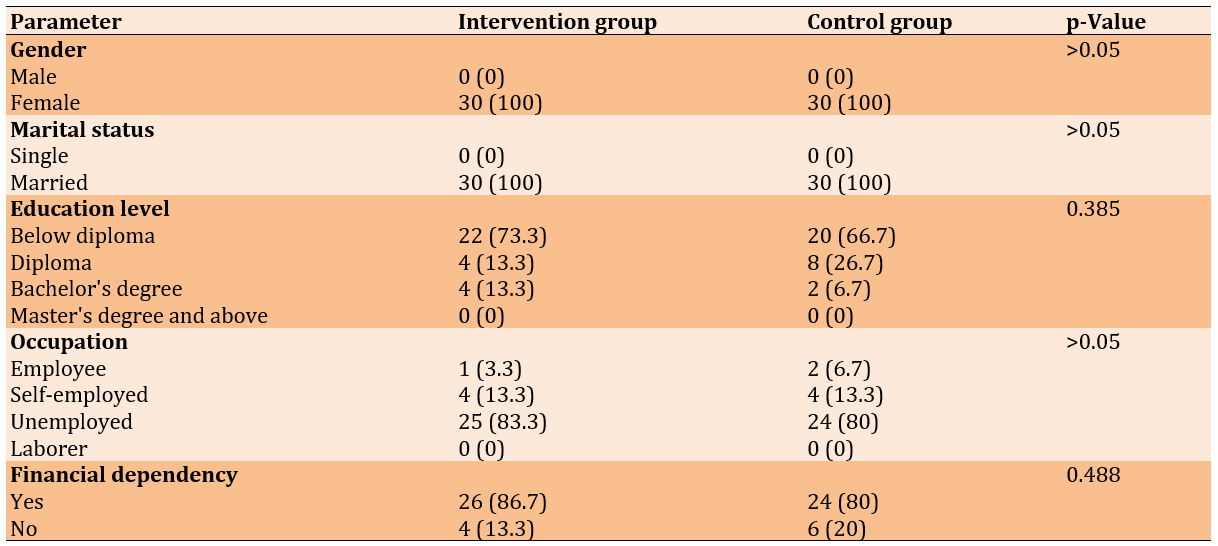

The mean age in the intervention group was 51.13±6.12 years, while in the control group it was 52.53±4.61, with no significant difference between the groups (p=0.321). The Chi-square test indicated no statistically significant difference between the two groups concerning caregivers’ demographic characteristics. Furthermore, all caregivers in both the intervention and control groups had no secondary caregiver, lacked financial support, and had no acute illness or stressful event in the last six months (p>0.05). The independent t-test also did not reveal a significant difference in average income (p=0.460) and caregiving duration (p=0.294) between the intervention and control groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of caregivers of veterans with diabetes

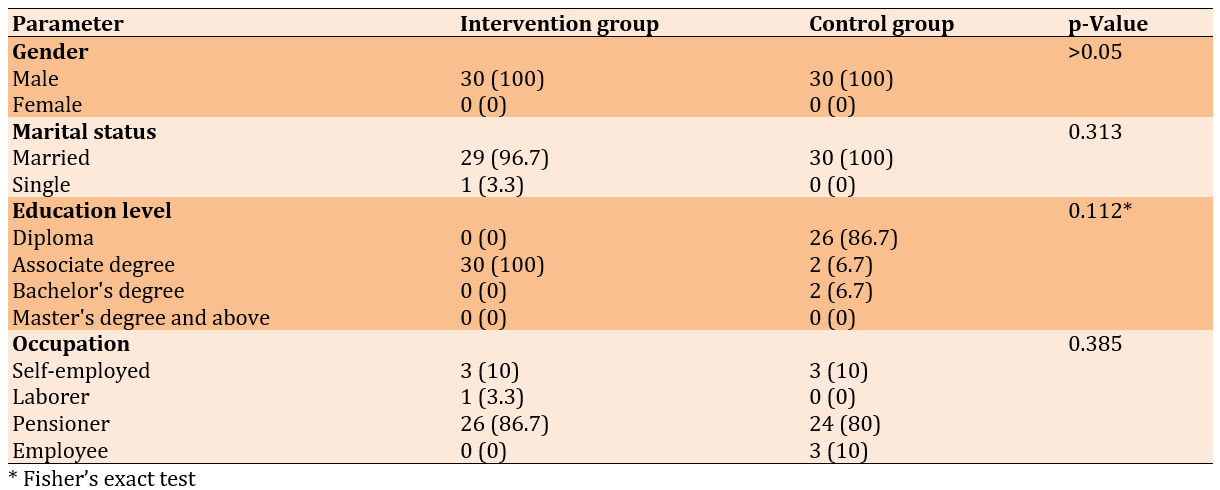

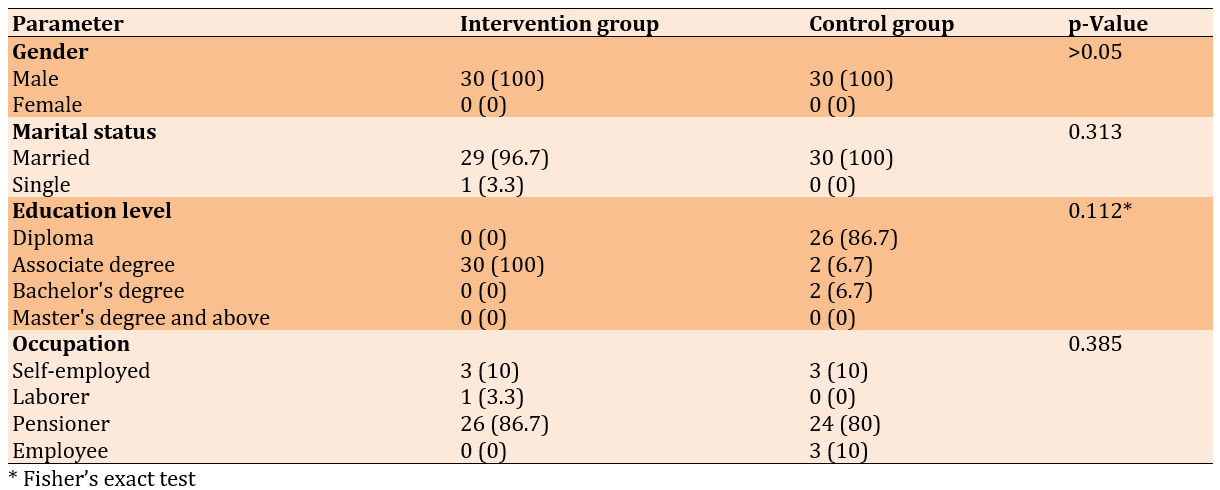

The mean age in the intervention group was 60.30±3.52 years, while in the control group it was 59.97±4.27, with no significant difference between the groups (p=0.746). The frequency distribution of veterans’ demographic characteristics was not different between the two groups. Additionally, all veterans in both groups had no acute illness or stressful events (p>0.05) and similar disability ratings (p = 0.956) in the last six months (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of veterans with diabetes

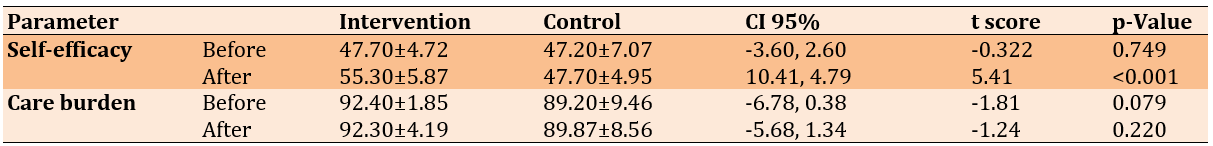

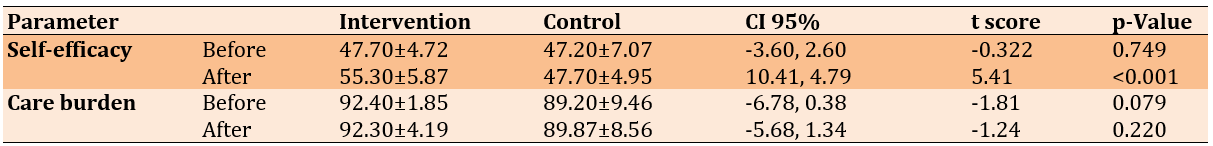

There was no significant difference in the mean self-efficacy before the intervention between the two groups (p=0.749). However, after the intervention, a statistically significant difference was observed in caregivers’ self-efficacy (p<0.001). Moreover, before (p=0.079) and after (p=0.220) the intervention, the average caregiving burden did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of the mean self-efficacy and care burden pre- and post-intervention in the intervention and control groups

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effect of a home visit empowerment program on the burden and self-efficacy of caregivers of veterans with diabetes. The home visit empowerment program significantly improved the self-efficacy of veteran caregivers. This improvement can be attributed to the needs-based and ability-focused training provided, which allowed caregivers to receive personalized instruction and enhance their caregiving skills. Similar results have been reported in previous studies. For instance, a study in Taiwan examined the effect of a home caregiver training program on self-efficacy in 48 participants and found that home-based training significantly improves caregivers’ self-efficacy [29]. Likewise, Hejazi et al. [30] highlight that self-efficacy is one of the most influential cognitive mechanisms and can be enhanced through education and attitude formation. Furthermore, Anggraini et al. [31] investigated the impact of diet management training on the self-efficacy and care performance of caregivers for diabetic patients. Their findings demonstrated that educational interventions improve both self-efficacy and management performance in home caregivers [31].

However, contrasting findings were reported in a study conducted in Thailand, reporting that a family-centered educational program consisting of three sessions does not improve caregivers’ ability to control the blood sugar levels of diabetic patients at home [32]. The researcher attributes this discrepancy to differences in the study population, research environment, content, and implementation methods.

The caregiving burden did not change significantly in either the intervention or control group after the home visit empowerment program. While the researcher initially expected that educational training would help reduce the burden, the findings did not support this hypothesis. This result differs from studies, such as the one conducted by Othman et al., which assessed the impact of a home-based training program on the caregiving behaviors of parents of children with diabetes. They reported that education on caregiving necessities and proper implementation improves patient symptoms and increases caregivers’ sense of responsibility, ultimately reducing their care-related burden [33].

The researcher speculates that the complexity and high demands of diabetes care may have contributed to caregivers continuing to experience a burden, despite receiving informational support through training. Caregivers may still feel overwhelmed by their responsibilities, which suggests that educational interventions alone may not be enough to alleviate burdens.

To effectively reduce caregiving stress, it may be necessary to incorporate non-educational interventions into the home visit programs. Psychosocial and spiritual support services could help caregivers manage their burdens through practical caregiving education. Weiss [34] argues that home visits, while necessary, are insufficient to fully meet the complex needs of families. Therefore, comprehensive, continuous, and family-centered programs are more effective. Furthermore, the success of such programs depends on the availability and quality of comprehensive support services, as well as caregivers’ capacity to access and engage with these services [34]. Similarly, Leung et al. [35] emphasize the importance of social support in caregiving. Their study suggests that increased self-efficacy, combined with strong family and social support, can significantly alleviate caregiving burden. This implies that caregivers who receive greater emotional and practical support from their families and communities experience lower caregiving stress [35].

The results of the study by Zupa et al. [36] align with our findings, indicating that a simultaneous caregiving program for veterans with diabetes, which involved both the veteran and their caregivers, does not significantly affect the caregivers’ caregiving burden [37]. Furthermore, studies conducted by Louie et al. [37] and Van Den Heuvel et al. [38], with interventions lasting 1 month and 2 months, respectively, also report an increase in caregivers’ knowledge with no significant impact on their psychological burden [37, 38].

However, some studies have shown a positive effect of educational interventions on caregiving burden. For instance, in a study conducted in Turkey, nurse-led home visits reduce the caregiving pressure experienced by home caregivers of asthma patients [39]. This intervention was conducted over five sessions across a three-month period, with both patients and caregivers receiving education and educational evaluations performed between sessions. This approach differs from the intervention in the present study, suggesting that the duration and frequency of sessions may play a significant role in reducing caregiving burden. Additionally, Yang et al. [40] reveal that a mindfulness-based training program significantly reduces caregiving stress among caregivers. The researchers emphasize the importance of using strategies to prevent or relieve caregiving stress, urging healthcare providers to implement such interventions as a mandatory part of caregiving support [40].

A potential limitation of this study is the receipt of additional information regarding interventions, which may have influenced the results and introduced confounding factors. Future studies should address this by controlling for such parameters and considering their potential impact on the outcomes.

This study demonstrated that the home visit empowerment program was effective in improving caregivers’ self-efficacy, which can enhance their caregiving capacity. However, since caregiving burden did not show significant improvement, it is likely that the educational intervention alone was insufficient to alleviate caregivers’ caregiving burden. The study suggests the need to supplement educational programs with additional interventions, including psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual support, to reduce caregiving burden.

Conclusion

The home visit empowerment program is effective in improving caregivers’ self-efficacy.

Acknowledgments: The researcher extends sincere thanks and appreciation to the Vice Chancellor for Research at Zabol and Golestan Universities of Medical Sciences, as well as to the caregivers and their veterans who wholeheartedly cooperated in this research. Their contributions were invaluable in conducting this study.

Ethical Permissions: This article is based on a master’s thesis in nursing approved by the Ethics Committee of Zabol University of Medical Sciences (code IR.ZBMU.REC.1402.080) with the clinical trial code IRCT20231018059763N.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Maghsoudloomahalli M (First Author), Main Researcher (40%); Shahdadi H (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (30%); Naderifar M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (10%); Abdollahimohammad A (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Podinehmoghadam M (Fifth Author), Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: No funding was received.

Veterans of the Iran-Iraq war experience numerous health challenges that extend to their families [1]. The presence of a chronic illness in a family member significantly impacts family dynamics, relationships, and overall family structure, presenting challenges in adaptation and management [2]. Research highlights the reciprocal influence between chronic patients and their families, where the health of one member affects the well-being of others. Family caregivers play an essential role in healthcare services, contributing significantly to the treatment and management of chronic diseases [3].

Over time, caregivers often experience exhaustion and fatigue due to the physical and mental toll of caregiving. In addition to attending to the veteran’s needs, they must also manage other household responsibilities [4]. The balance between the patient’s demands and the caregiver’s resources and capabilities often leads to caregiving burden, which encompasses physical, emotional, social, and financial strains [5]. Symptoms of caregiving burden include depression, anxiety, feelings of entrapment, and, in severe cases, helpless decision-making or even abandonment of care [6]. Studies indicate that caregivers of veterans frequently experience moderate levels of caregiving burden [7].

Several interventions have been proposed to alleviate caregiving burden, with medical and nursing teams playing a crucial role. These interventions generally focus on empowering caregivers through education, psychological support, and social assistance [8]. In contrast to caregiving burden, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform caregiving tasks effectively. High self-efficacy fosters motivation and belief in one’s caregiving abilities, whereas a decline in self-efficacy can negatively impact both the caregiver’s and the veteran’s health [9, 10]. Engaging caregivers in the treatment process through education can enhance their confidence, improve patient self-care, and increase overall quality of life. While caregivers are not obligated to acquire caregiving knowledge, it is essential for the healthcare team to emphasize their critical role as the veteran’s primary support system [11].

One effective approach to caregiver education is home visits, which tailor educational content to caregivers’ specific needs and available resources [12, 13]. Home visits help deliver healthcare education to individuals with chronic conditions, particularly those living in remote areas with limited access to medical facilities [14]. These programs empower both patients and caregivers, promoting greater independence [15]. The growing recognition of the importance of home visits has led to specialized training programs for nurses in various communities [16]. Proper education and a well-structured home care environment provide continuous support for caregivers and chronic patients while also serving as a cost-effective solution [13].

Beyond the direct consequences of war, veterans experience a higher prevalence of various disorders and diseases compared to the general population. Studies indicate that the prevalence of diabetes among war-injured soldiers in the United States is 25%, while research in Iran has reported a 7.5% prevalence of diabetes among neuropsychiatric veterans [17, 18]. Furthermore, diabetes control among individuals remains suboptimal due to poor adherence to treatment regimens, lifestyle modifications, and disease-related complications [19, 20]. Since more than 95% of diabetes care is managed within the home setting [21], caregivers face significant burdens.

Although numerous studies have examined caregiver burden and self-efficacy, there is a paucity of research specifically focusing on caregivers of Iranian-Iraqi war veterans with diabetes. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effect of a home visit empowerment program on the burden and self-efficacy of caregivers of veterans with diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This single-blind randomized clinical trial was performed on caregivers of veterans diagnosed with diabetes in 2024 at selected healthcare centers in Gorgan, Iran. The sample size was initially estimated at a minimum of 22 participants per group, based on a 95% confidence level, 80% test power, and a 30% probability of attrition [22]. However, to enhance generalizability, 32 participants per group (a total of 64 participants) were recruited. Due to illness-related dropouts, 60 participants completed the study and were included in the final analysis. The sampling method involved purposive selection of health care facilities followed by stratified random sampling of eligible caregivers in the selected facilities.

Caregivers were eligible if they provided full-time care for a veteran with at least a 50% disability and diabetes, were in good health at the time of the study, had at least a fifth-grade education, were not simultaneously caring for another patient, and had not experienced a stressful event in the past six months. Participants were excluded if they withdrew from the study, experienced the death of the caregiver or veteran, developed an acute illness, required hospitalization during the study, encountered a stressful event during the study, or missed two consecutive home visit sessions [4, 23].

Demographic data were collected using a veteran demographic questionnaire, which included details, such as age, gender, economic status, duration of illness, and percentage of disability. Additionally, caregiver demographic information was gathered, covering age, gender, duration of care, caregiver-to-veteran relationship, and education level.

To assess caregiver self-efficacy, Sherer’s Self-Efficacy Questionnaire was used. This 17-item scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items 1, 3, 8, 9, 13, and 15 are reverse-scored. The total possible score ranges from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. Sherer reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 for the general self-efficacy scale. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire have been confirmed in multiple studies conducted in Iran [24, 25].

To measure caregiving burden, the Caregiver Burden Inventory by Novak and Guest, developed in 1989, was used. This 24-item questionnaire is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always), with a total score ranging from 24 to 120. Higher scores indicate a greater caregiving burden [26]. The validity of this questionnaire was confirmed by Abbasi et al. using content and face validity, and its reliability was established with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.69 to 0.87 for subscales and 0.80 for the total questionnaire [11]. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the questionnaire have also been confirmed in various studies in Iran [26, 27].

A list of veterans who met the inclusion criteria was first compiled. Eligible veterans were defined as those with a disability rating of 50% or higher and a confirmed diagnosis of diabetes. Using this list, their caregivers were identified and numbered. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group, with the first randomly selected caregiver placed in the intervention group and the next in the control group. This alternation continued until all participants were assigned, ensuring equal distribution across groups. After obtaining written informed consent, the intervention was initiated. Ethical principles were fully observed in this research. The research objectives were explained to the participants, who were informed about the study process. The confidentiality of participants’ identities and research data was maintained. Additionally, participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

A diabetes education program was developed using relevant sources and under the guidance of diabetes experts and faculty members. After incorporating expert feedback, the program was validated. The intervention consisted of four face-to-face training sessions, each lasting 40 to 60 minutes, conducted in veterans’ homes over a four-week period. Sessions were scheduled weekly, and prior coordination was ensured with caregivers.

The control group received only routine training through an educational pamphlet. The intervention period lasted three months, during which caregivers in the intervention group received follow-up phone calls to address any training-related questions. Both groups were monitored for compliance with exclusion criteria [28]. At the end of the study, the educational content provided to the intervention group was also given to the control group in booklet form as an appreciation for their participation (Table 1).

Table 1. Home visit empowerment program sessions and content list

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 22 using the Chi-square test, independent t-test, and Fisher’s exact test to compare the two groups.

Findings

The mean age in the intervention group was 51.13±6.12 years, while in the control group it was 52.53±4.61, with no significant difference between the groups (p=0.321). The Chi-square test indicated no statistically significant difference between the two groups concerning caregivers’ demographic characteristics. Furthermore, all caregivers in both the intervention and control groups had no secondary caregiver, lacked financial support, and had no acute illness or stressful event in the last six months (p>0.05). The independent t-test also did not reveal a significant difference in average income (p=0.460) and caregiving duration (p=0.294) between the intervention and control groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of caregivers of veterans with diabetes

The mean age in the intervention group was 60.30±3.52 years, while in the control group it was 59.97±4.27, with no significant difference between the groups (p=0.746). The frequency distribution of veterans’ demographic characteristics was not different between the two groups. Additionally, all veterans in both groups had no acute illness or stressful events (p>0.05) and similar disability ratings (p = 0.956) in the last six months (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the frequency of demographic characteristics of veterans with diabetes

There was no significant difference in the mean self-efficacy before the intervention between the two groups (p=0.749). However, after the intervention, a statistically significant difference was observed in caregivers’ self-efficacy (p<0.001). Moreover, before (p=0.079) and after (p=0.220) the intervention, the average caregiving burden did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of the mean self-efficacy and care burden pre- and post-intervention in the intervention and control groups

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effect of a home visit empowerment program on the burden and self-efficacy of caregivers of veterans with diabetes. The home visit empowerment program significantly improved the self-efficacy of veteran caregivers. This improvement can be attributed to the needs-based and ability-focused training provided, which allowed caregivers to receive personalized instruction and enhance their caregiving skills. Similar results have been reported in previous studies. For instance, a study in Taiwan examined the effect of a home caregiver training program on self-efficacy in 48 participants and found that home-based training significantly improves caregivers’ self-efficacy [29]. Likewise, Hejazi et al. [30] highlight that self-efficacy is one of the most influential cognitive mechanisms and can be enhanced through education and attitude formation. Furthermore, Anggraini et al. [31] investigated the impact of diet management training on the self-efficacy and care performance of caregivers for diabetic patients. Their findings demonstrated that educational interventions improve both self-efficacy and management performance in home caregivers [31].

However, contrasting findings were reported in a study conducted in Thailand, reporting that a family-centered educational program consisting of three sessions does not improve caregivers’ ability to control the blood sugar levels of diabetic patients at home [32]. The researcher attributes this discrepancy to differences in the study population, research environment, content, and implementation methods.

The caregiving burden did not change significantly in either the intervention or control group after the home visit empowerment program. While the researcher initially expected that educational training would help reduce the burden, the findings did not support this hypothesis. This result differs from studies, such as the one conducted by Othman et al., which assessed the impact of a home-based training program on the caregiving behaviors of parents of children with diabetes. They reported that education on caregiving necessities and proper implementation improves patient symptoms and increases caregivers’ sense of responsibility, ultimately reducing their care-related burden [33].

The researcher speculates that the complexity and high demands of diabetes care may have contributed to caregivers continuing to experience a burden, despite receiving informational support through training. Caregivers may still feel overwhelmed by their responsibilities, which suggests that educational interventions alone may not be enough to alleviate burdens.

To effectively reduce caregiving stress, it may be necessary to incorporate non-educational interventions into the home visit programs. Psychosocial and spiritual support services could help caregivers manage their burdens through practical caregiving education. Weiss [34] argues that home visits, while necessary, are insufficient to fully meet the complex needs of families. Therefore, comprehensive, continuous, and family-centered programs are more effective. Furthermore, the success of such programs depends on the availability and quality of comprehensive support services, as well as caregivers’ capacity to access and engage with these services [34]. Similarly, Leung et al. [35] emphasize the importance of social support in caregiving. Their study suggests that increased self-efficacy, combined with strong family and social support, can significantly alleviate caregiving burden. This implies that caregivers who receive greater emotional and practical support from their families and communities experience lower caregiving stress [35].

The results of the study by Zupa et al. [36] align with our findings, indicating that a simultaneous caregiving program for veterans with diabetes, which involved both the veteran and their caregivers, does not significantly affect the caregivers’ caregiving burden [37]. Furthermore, studies conducted by Louie et al. [37] and Van Den Heuvel et al. [38], with interventions lasting 1 month and 2 months, respectively, also report an increase in caregivers’ knowledge with no significant impact on their psychological burden [37, 38].

However, some studies have shown a positive effect of educational interventions on caregiving burden. For instance, in a study conducted in Turkey, nurse-led home visits reduce the caregiving pressure experienced by home caregivers of asthma patients [39]. This intervention was conducted over five sessions across a three-month period, with both patients and caregivers receiving education and educational evaluations performed between sessions. This approach differs from the intervention in the present study, suggesting that the duration and frequency of sessions may play a significant role in reducing caregiving burden. Additionally, Yang et al. [40] reveal that a mindfulness-based training program significantly reduces caregiving stress among caregivers. The researchers emphasize the importance of using strategies to prevent or relieve caregiving stress, urging healthcare providers to implement such interventions as a mandatory part of caregiving support [40].

A potential limitation of this study is the receipt of additional information regarding interventions, which may have influenced the results and introduced confounding factors. Future studies should address this by controlling for such parameters and considering their potential impact on the outcomes.

This study demonstrated that the home visit empowerment program was effective in improving caregivers’ self-efficacy, which can enhance their caregiving capacity. However, since caregiving burden did not show significant improvement, it is likely that the educational intervention alone was insufficient to alleviate caregivers’ caregiving burden. The study suggests the need to supplement educational programs with additional interventions, including psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual support, to reduce caregiving burden.

Conclusion

The home visit empowerment program is effective in improving caregivers’ self-efficacy.

Acknowledgments: The researcher extends sincere thanks and appreciation to the Vice Chancellor for Research at Zabol and Golestan Universities of Medical Sciences, as well as to the caregivers and their veterans who wholeheartedly cooperated in this research. Their contributions were invaluable in conducting this study.

Ethical Permissions: This article is based on a master’s thesis in nursing approved by the Ethics Committee of Zabol University of Medical Sciences (code IR.ZBMU.REC.1402.080) with the clinical trial code IRCT20231018059763N.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution: Maghsoudloomahalli M (First Author), Main Researcher (40%); Shahdadi H (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher (30%); Naderifar M (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (10%); Abdollahimohammad A (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (10%); Podinehmoghadam M (Fifth Author), Discussion Writer (10%)

Funding/Support: No funding was received.

Keywords:

Home Visits [MeSH], Care Burden [MeSH], Self-Efficacy [MeSH], Caregivers [MeSH], Veterans [MeSH], Diabetes [MeSH]

References

1. Ghahramani S, Ghaedrahmat M, Saberi N, Ghanei-Gheshlagh R, Dalvand P, Barzgaran R. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the quality of life of Iranian veterans' wives. J Mil Med. 2022;24(4):1260-9. [Persian] [Link]

2. Madani FS, Zarani F. Managing chronic illness in the family: A systematic review. J Fam Res. 2022;18(1):57-73. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.52547/JFR.18.1.57]

3. Parandeh AK, Saeed KB, Salari MM, Alhani FA. Effect of family-centered empowerment model on the quality of life in chemical warfare veterans: Randomized controlled clinical trial. J Mil Med. 2018;20(5):554-62. [Persian] [Link]

4. Raisimanesh M, Seyrafi M, Mashayekh M. Predicting illness attitude based on caregiver burden and stress coping styles in disabled veterans. Mil Psychol. 2020;11(42):19-30. [Persian] [Link]

5. Adili D, Dehghani-Arani F. The relationship between caregiver's burden and patient's quality of life in women with breast cancer. J Res Psychol Health. 2018;12(2):30-9. [Link]

6. Safiri S, Moghimian M, Sadeghi N, Sasani L. The effect of continuous care model on self-efficacy and care burden of parents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;10(4):61-70. [Persian] [Link]

7. Thandi G, Harden L, Cole L, Greenberg N, Fear NT. Systematic review of caregiver burden in spouses and partners providing informal care to wounded, injured or sick (WIS) military personnel. J R Army Med Corps. 2018;164(5):365-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/jramc-2017-000821]

8. Sousa H, Ribeiro O, Afreixo V, Costa E, Paúl C, Ribeiro F, et al. "Should WE Stand Together?": A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of family-based interventions for adults with chronic physical diseases. Fam Process. 2021;60(4):1098-116. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/famp.12707]

9. Burger K, Samuel R. The role of perceived stress and self-efficacy in young people's life satisfaction: A longitudinal study. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(1):78-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10964-016-0608-x]

10. Zanjari N, Namjoo S, Aminzadeh DM, Delbari A. Relationship between self-efficacy and depression among family caregivers of chemical warfare elderly veterans. Iran J War Public Health. 2019;11(4):223-31. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijwph.11.4.223]

11. Abbasi A, Shamsizadeh M, Asayesh H, Rahmani H, Hosseini S, Talebi M. The relationship between caregiver burden with coping strategies in family caregivers of cancer patients. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;1(3):62-71. [Persian] [Link]

12. Unwin BK, Jerant AF. The home visit. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(5):1481-8. [Link]

13. Dehi M, Norozi K, Aghajari P, Khoahbakht M, Vosoghi N. The effect of home visit on quality of life of patients with type II diabetes. Iran J Diabetes Metab. 2018;17(1):31-8. [Persian] [Link]

14. Torres HD, Santos LM, Cordeiro PM. Home visit: An educational health strategy for self-care in diabetes. ACTA PAULISTA DE ENFERMAGEM. 2014;27(1):23-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/1982-0194201400006]

15. Gholizadeh M, Akrami R, Tadayonfar M, Akbarzadeh R. An evaluation on the effectiveness of patient care education on quality of life of stroke caregivers: A randomized field trial. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2016;22(6):955-64. [Persian] [Link]

16. Tabatabaee A, Mohammadnejad E, Karimi A, Salehi Z, Sadat Izadi-Avanji F. The effect of family-centered self-care program based on home visits on adherence to physical activity of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022;11(1):50-7. [Persian] [Link]

17. Nejati V, Ahmadi K. Evaluation of epidemiology of chronic disease in Iranian psychiatric veterans. Iran J War Public Health. 2010;2(4):8-12. [Persian] [Link]

18. Liu Y, Sayam S, Shao X, Wang K, Zheng S, Li Y, et al. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among veterans, United States, 2005-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E135. [Link] [DOI:10.5888/pcd14.170230]

19. Davoodi M, Dindamal B, Dargahi H, Faraji Khiavi F. Barriers and incentives for patients with type II diabetic referring to healthcare centers: A qualitative study. J Diabetes Nurs. 2020;8(4):1223-36. [Persian] [Link]

20. Torki-Harchegani F, Shirazi M, Keshvari M, Abazari P. The effect of home visit program on self-management behaviors and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2020;38(575):310-6. [Persian] [Link]

21. Setyoadi, Meiliana SW, Hakim FO, Hayati YS, Kristianingrum ND, Kartika AW, et al. The burden of family caregivers in the care of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A literature review. J Rural Community Nurs Pract. 2024;2(1):40-7. [Link] [DOI:10.58545/jrcnp.v2i1.207]

22. Wasmani A, Rahnama M, Abdollahimohammad A, Badakhsh M, Hashemi Z. The effect of family-centered education on the care burden of family caregivers of the elderly with cancer: A quasi-experimental study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23(3):1077-82. [Link] [DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.3.1077]

23. Kouhsari M, Shamsalinia A, Navabi N, Jannati Y. Effect of family-oriented education on care burden and anxiety of caregivers of the elderly with type 2 diabetes. Casp J Health Aging. 2022;7(2):61-73. [Persian] [Link]

24. Azad Marzabadi E, Fathi-Ashtiani A, Ahmadi-Zade MJ, Anisi J, Zamani-Nasab R. Relationship between physical-mental health and spirituality with self-efficacy in military staff. J Mil Med. 2015;16(4):217-23. [Persian] [Link]

25. Omidi B, Sabet M, Ahadi H, Nejat H. Effectiveness of emotion regulation training on perceived stress, self-efficacy and sleep quality in the elderly with type 2 diabetes (T2D). J Prev Med. 2022;9(2):132-43. [Persian] [Link]

26. Ebrahimi H, Sanagoo A, Behnampour N, Jouybari L. Care burden of home caregivers of patients with COVID-19. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2022;32(208):75-83. [Persian] [Link]

27. Ali Asgari Rizi M, Manshaee G. The effectiveness of mindfulness training on caring pressure and compassion fatigue in caregivers of heart transplant candidates. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2024;12(3):80-90. [Persian] [Link]

28. Omidi A, Miri F, Khodaveisi M, Karami M, Mohammadi N. The effect of training home care to type-2 diabetic patients on controlling blood glucose levels in patients admitted to the diabetes research center of Hamadan. Avicenna J Nurs Midwifery Care. 2014;22(3):24-32. [Persian] [Link]

29. Huang HL, Shyu YI, Chen MC, Chen ST, Lin LC. A pilot study on a home-based caregiver training program for improving caregiver self-efficacy and decreasing the behavioral problems of elders with dementia in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(4):337-45. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/gps.835]

30. Hejazi E, Sadeghi N, Khatoon Khaki S. A study on the relationship between teachers' job attitude, sense of efficacy and collective efficacy with their job commitment. J Educ Innov. 2012;11(42):7-29. [Persian] [Link]

31. Anggraini R, Suryawati C, Rachma N. Effects of dietary management education on self-efficacy and caregiver practice in dietary care of family members with type 2 DM. Indones J Nurs Midwifery. 2018;6(3):211-8. [Link] [DOI:10.21927/jnki.2018.6(3).43-50]

32. Wichit N, Mnatzaganian G, Courtney M, Schulz P, Johnson M. Randomized controlled trial of a family-oriented self-management program to improve self-efficacy, glycemic control and quality of life among Thai individuals with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;123:37-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2016.11.013]

33. Othman S, Hasan S, Garjees N. Effects of a home-based nursing intervention program on caregivers care adherence of children affected with type I diabetes mellitus. J Med Chem Sci. 2023;6(10):2319-26. [Link]

34. Weiss HB. Home visits: Necessary but not sufficient. Future Child. 1993;3(3):113-28. [Link] [DOI:10.2307/1602545]

35. Leung DYP, Chan HYL, Chiu PKC, Lo RSK, Lee LLY. Source of social support and caregiving self-efficacy on caregiver burden and patient's quality of life: A path analysis on patients with palliative care needs and their caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5457. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17155457]

36. Zupa MF, Lee A, Piette JD, Trivedi R, Youk A, Heisler M, et al. Impact of a dyadic intervention on family supporter involvement in helping adults manage type 2 diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(4):761-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11606-021-06946-8]

37. Louie SW, Liu PK, Man DW. The effectiveness of a stroke education group on persons with stroke and their caregivers. Int J Rehabil Res. 2006;29(2):123-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/01.mrr.0000191851.03317.f0]

38. Van Den Heuvel ET, De Witte LP, Nooyen-Haazen I, Sanderman R, Meyboom-de Jong B. Short-term effects of a group support program and an individual support program for caregivers of stroke patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40(2):109-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00066-X]

39. Ugur HG, Erci B. The effect of home care for stroke patients and education of caregivers on the caregiver burden and quality of life. Acta Clin Croat. 2019;58(2):321-32. [Link]

40. Yang SY, Fu SH, Hsieh PL, Lin YL, Chen MC, Lin PH. Improving the care stress, life quality, and family functions for family-caregiver in long-term care by home modification. Ind Health. 2022;60(5):485-97. [Link] [DOI:10.2486/indhealth.2021-0176]