Volume 17, Issue 1 (2025)

Iran J War Public Health 2025, 17(1): 29-35 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.IAU.TMU.REC.1403.042

History

Received: 2025/01/25 | Accepted: 2025/02/28 | Published: 2025/03/2

Received: 2025/01/25 | Accepted: 2025/02/28 | Published: 2025/03/2

How to cite this article

Keyvan Nasab S, Hamid B, Ganji L, Amini M, Pashmdarfard M, Davari Z. Relationship of Loneliness, Perceived Social Support, and Dysfunctional Attitudes with Death Anxiety in Older Adults; the Mediating Role of Spiritual Health. Iran J War Public Health 2025; 17 (1) :29-35

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1549-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1549-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Educational Psychology and Rehabilitation Counselling, Tehran Medical Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- “Rehabilitation Research Centre” and “Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences”, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- “Rehabilitation Research Centre” and “Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences”, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (765 Views)

Introduction

Death anxiety encompasses a range of thoughts, fears, and emotions associated with the concept of mortality [1]. Available literature, including comprehensive reviews of research undertaken in nonclinical populations, has shown that death anxiety is a prevalent phenomenon within the general population [2]. In late adulthood, individuals often become increasingly preoccupied with the concept of death, engaging in discussions about it more frequently. This heightened awareness is frequently prompted by observable physical changes, an uptick in illness and disability, and the bereavement of relatives and friends. While experiencing a certain degree of anxiety regarding death is normative, excessive manifestations of such anxiety may hinder psychological adjustment and functional capabilities. Notably, the predominant human response to death tends to be characterized by feelings of hatred, hostility, and disgust, which are often intermingled with fear. The intensity and expression of these emotions can differ significantly among individuals, influenced by temporal, racial, religious, and cultural contexts [3].

Another pertinent variable influencing individuals' mental health, particularly among older adults, is loneliness. Loneliness represents a profoundly distressing experience that can precipitate severe psychological and physical health issues [4]. Research has identified a correlation between loneliness and various adverse outcomes, including depression, suicidal tendencies, substance abuse, feelings of hopelessness, and aggravation of physical ailments [5]. Some scholars have conceptualized loneliness in terms of the discrepancy between desired and actual levels of social relationships, assessing both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. Thus, the experience of loneliness is underpinned by the gap between an individual’s aspirations regarding interpersonal connections and the reality of their existing relationships and intimacy. As this disparity increases, so too does the sensation of loneliness. Given the significant implications of loneliness for psychological and physical health, it is imperative to analyze the factors contributing to it [6].

Several factors contribute to loneliness among the elderly. A particularly salient variable is perceived social support. Researchers and experts in gerontology argue that the perception of social support is instrumental in mitigating the adverse physiological complications associated with various medical conditions in older adults. It can enhance levels of self-care and self-confidence, positively influencing older adults' physical, mental, and social well-being, thereby markedly improving their overall performance and quality of life [7].

In the context of older adults, perceived social support not only affects their psychological status but also plays a pivotal role in determining the severity of their medical conditions, which can subsequently impact their physical and mental health [8]. Empirical studies indicate that augmenting the perceived social support available to physically ill elderly patients can lead to a reduction in mortality rates and the severity of their illnesses. Furthermore, older adults with robust social support networks are observed to face a lower risk of disease progression and exhibit diminished psychological vulnerability [9].

Despite the recognized importance of perceived social support, there exists a notable paucity of research addressing its implications for loneliness, death anxiety, and quality of life for older adults. Consequently, an additional objective of the present study is to explain the role of perceived social support within this demographic [10].

Moreover, depression among older adults frequently correlates with the presence of dysfunctional attitudes [10]. According to Aaron Beck's theoretical framework, these dysfunctional attitudes represent enduring personality traits that predispose individuals to depressive disorders. They are characterized by negative cognitive schemas concerning the self, the world, and the future, often conceptualized as the negative cognitive triangle [11].

Historically, health has been delineated through specific dimensions encompassing physical, mental, and social well-being. Some scholars have advocated for the inclusion of spiritual health within this holistic model of health, prompting increased attention from policymakers and community health planners across various governmental entities. Research indicates that spiritual health is inextricably linked with other biological dimensions of an individual's life, thereby underscoring that achieving optimal quality of life necessitates the integration of these diverse health dimensions [12].

Spiritual health encompasses the individual's spiritual experiences from two distinct perspectives: The religious health perspective, which examines how individuals understand their health concerning a higher power, and the existential health perspective, which focuses on social and psychological concerns and how individuals adapt to their societal and environmental contexts. Diverse definitions of spiritual health exist. Some posit that spirituality is inherently derived from religious beliefs, leading to variations in definitions of spiritual health across different faiths. Factors such as life events, belief systems, religious practices, gender, and individual life stages significantly influence one's spirituality [13].

The Academy of Medical Sciences of Iran has articulated a definition of spiritual health, describing it as a dynamic state characterized by varying levels of insight, tendencies, and abilities that facilitate the elevation of the soul toward a connection with the Divine. This definition emphasizes the harmonious and balanced utilization of all internal capacities in

alignment with overarching spiritual goals, manifesting in internal and external behaviors reflecting this pursuit of connection with God, self, society, and nature [14].

This study aimed to investigate the correlation between loneliness, death anxiety, perceived social support, and spiritual health. A critical focus was placed on evaluating the mediating role of spiritual health in this relationship, aiming to clarify how it may serve as a buffer against the effects of loneliness and dysfunctional attitudes on death anxiety.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sampling

In this descriptive cross-sectional study, which lasted from May to July 2024, women aged 60 and above who were members of the Shahr-e Rey Retirement Institution of Tehran Province and lived in Tehran were invited to participate in volunteer through direct invitations. Any health condition or sudden event that disrupted the data collection process resulted in the participant's exclusion.

Considering the number of parameters, increasing statistical power, and managing potential participant dropouts [15], the sample size was calculated to be at least 384 individuals. Considering the total number of members at the Shahr-e Ray Retirement Center in Tehran Province was 1,322, the Cochran formula was applied, resulting in an estimated sample size of approximately 386.58 individuals. This was adjusted to account for possible dropouts, confirming a target sample size of 384 individuals. The same figure was ultimately reached in both approaches to determining the sample size. A convenience sampling method was employed to select participants.

Measures

Death Anxiety Scale (DAS): developed and validated by Templer in 1970, is one of the most widely utilized instruments for assessing death anxiety [16]. This self-administered questionnaire consists of 15 true-false questions to evaluate an individual's attitudes toward death. It operates within the dimensions of general anxiety, specific anxieties related to death, and fears surrounding surgical interventions. A 'yes' response indicates the presence of an anxiety-provoking factor in the individual, suggesting a level of psychological distress. The scoring on the DAS ranges from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater levels of death anxiety [16]. The test-retest validity of the Persian version of the DAS has been reported at 0.85, while the split-half reliability coefficient stands at 0.62. The overall reliability, as measured by Cronbach's alpha, is 0.73 [16]. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the 15 questions of the DAS was determined to be 0.78, indicating a consistent and reliable measure of death anxiety.

Revised Russell Loneliness Scale (R-RLS): developed by Russell et al., is a psychometric instrument comprising 20 items that utilize a 4-point Likert scale ranging from "never" (score of 1) to "always" (score of 4) [17]. The scale is evenly divided, containing 10 positively and 10 negatively framed items [17]. The overall score for the scale is calculated by summing the responses to all questions, yielding a total score that ranges from 20 to 80 [17].

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): was developed by Zimet et al. and comprises 12 items that are categorized into three distinct subscales: Social support received from family (four items), social support received from friends (four items), and social support received from significant others (four items) [18]. This scale assesses perceived social support from familial, friendly, and other significant relationships within an individual’s social network. The developers reported satisfactory validity and reliability for the MSPSS [18]. Similarly, Salimi & Bozorgpour demonstrated the reliability of the Persian version of the MSPSS, finding Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.86, 0.86, and 0.82 for the dimensions of social support received from family, friends, and significant others, respectively [19].

Dysfunctional Attitudes Questionnaire (DAQ): was developed by Weissman & Beck based on Beck's theory regarding the cognitive structure of depression [20]. This questionnaire consists of four subscales and 26 items; Achievement-perfectionism, the need for approval from others, the need to please others, and vulnerability to performance evaluation. Ebrahimi et al. have reported the internal consistency of the 26-item version of the DAQ using a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 [21].

Spiritual Health Assessment Scale (SHAS): The scale developed by Lata Gaur & Sharma comprises three distinct subscales and 21 items [22]. These subscales are categorized as follows: 1) self-growth, 2) self-actualization, and 3) self-realization. Each subscale is further delineated into seven specific components. The self-growth subscale encompasses the components of foresight, gratitude, generosity, charity, tolerance, self-control, and ethical behavior. The self-actualization subscale includes introspection, purpose in life, pathways in life, strengths, weaknesses, solutions, and considerations of the end of life. The self-realization subscale comprises recklessness, yoga, satisfaction, freedom, understanding of inner truths, happiness, and the sixth sense [22].

Procedure

After obtaining the ethical approval, data was collected by the trained individuals. Each participant completed all measures, and informed consent was obtained before they engaged with the questionnaires.

Data analysis

We utilized Pearson correlation coefficients to analyze the relationships between loneliness, perceived social support, death anxiety, spiritual

health, and death anxiety. We conducted path analysis to assess both the direct and indirect effects among the constructs. Several key criteria were assessed to evaluate model fit indices accurately. A chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio of less than 3 was considered acceptable, alongside other metrics such as the adaptive fit index, fitness index, and reduced fitness index, which should ideally be greater than or equal to 0.9. A square root of the approximation error of less than 0.08, coupled with a non-adaptive fit index exceeding 0.9, serves as additional indicators of model appropriateness.

All analyses were performed using SPSS 22 and AMOS 22 software at a significance level of p<0.05.

Findings

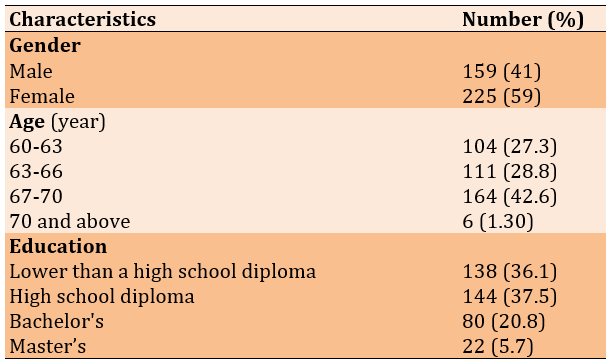

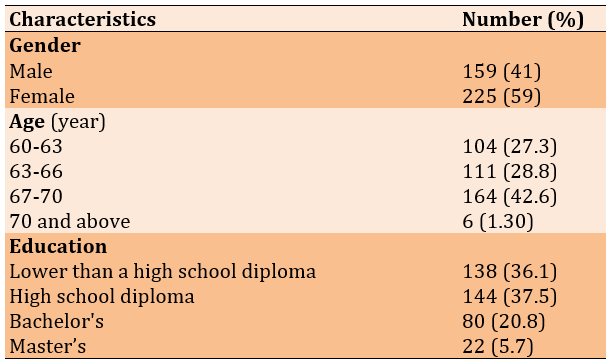

The mean age of the participants was 69.0±7.4 years. Most participants were female (59.0%), between 67 and 70 years old (42.6%), and with a high school diploma (37.5%; Table 1).

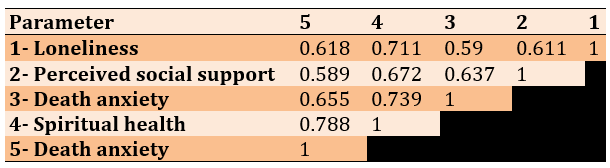

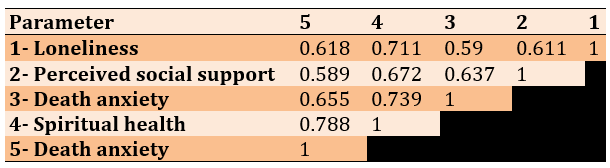

There were significant positive correlations between all the research parameters (p<0.001; Table 2).

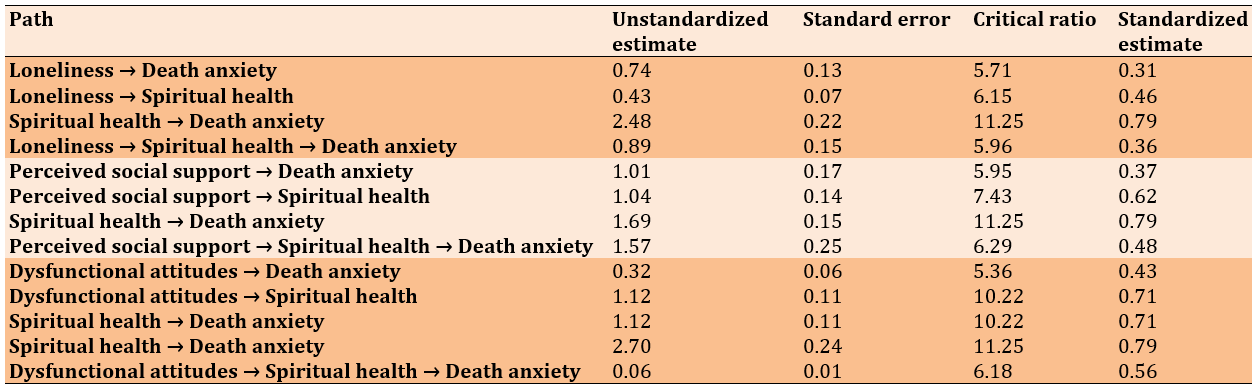

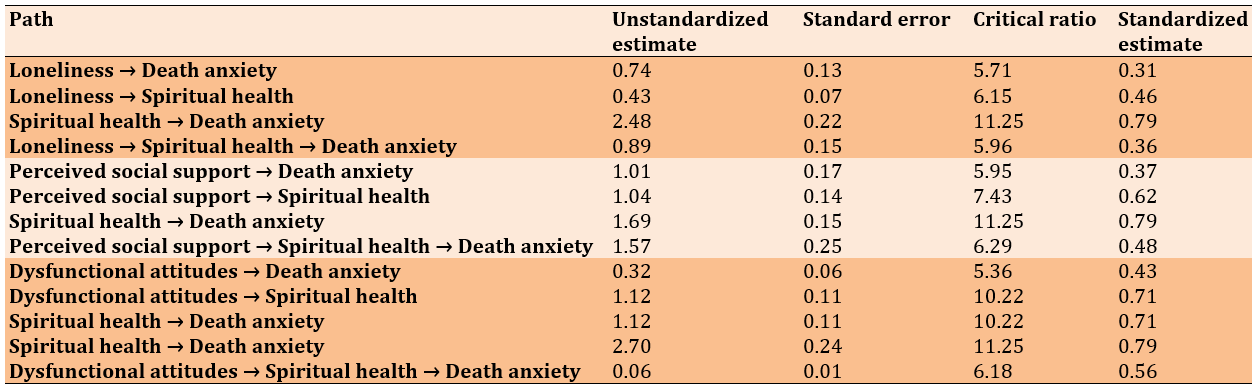

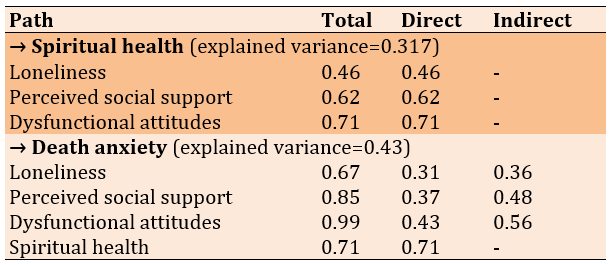

Path analysis was used to examine the relationship between “feelings of loneliness”, “perceived social support”, “dysfunctional attitudes” and “death anxiety”, considering the mediating role of spiritual health (Table 3).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

Table 2. The correlation coefficient between research parameters (all significant at p<0.001)

Table 3. Path analysis results

There was a significant effect of loneliness on spiritual health, with a coefficient of 0.46. Furthermore, the effect of spiritual health on death anxiety was quantified at 0.79. Both of these effects achieved statistical significance at the 99% confidence level. The calculation of the indirect effect of loneliness on death anxiety, derived from the product of these coefficients (0.46×0.79), yielded an indirect effect of 0.36. The critical ratio for this indirect effect exceeded 2.57 (p<0.01), thereby supporting the conclusion that there existed a noteworthy relationship between loneliness and death anxiety that was mediated by spiritual health. However, it was pertinent to note that loneliness maintained a significant direct effect on death anxiety, suggesting that the role of spiritual health as a mediator was relatively minor.

Similarly, the analysis revealed that the coefficient representing the effect of perceived social support on spiritual health was 0.62. In contrast, the effect of spiritual health on death anxiety again stood at 0.79, with both effects being significant at the 99% confidence level. The indirect effect of perceived social support on death anxiety, calculated by multiplying these coefficients (0.62×0.79), resulted in an indirect effect of 0.48. The critical ratio for this indirect effect also surpassed 2.57 (p<0.01), reinforcing the presence of a significant relationship between perceived social support and death anxiety through spiritual health (Table 4).

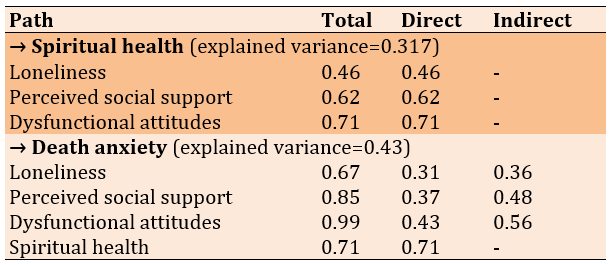

Table 4. Total, direct, and indirect standard coefficients of the model

Discussion

This study sought to examine the relationship between loneliness, mental health, and dysfunctional attitudes while also examining the mediating role of spiritual health among community-dwelling elderly individuals. The findings reveal a significant correlation among cognitive components, including loneliness, dysfunctional attitudes, and perceived social support, alongside their impact on spiritual health. These results suggest that loneliness may adversely affect both mental and spiritual well-being. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of social connections and support in fostering spiritual health. Engagement in activities such as meditation, yoga, and creative expression is posited to mitigate feelings of loneliness and enhance spiritual well-being, thereby underscoring the multifaceted interplay between these variables in the elderly population.

In light of the findings from the present study, robust interpersonal connections, a profound sense of meaning and purpose in life, and experiences of coherence and personal growth all significantly contribute to an individual’s spiritual health. Conversely, the experience of loneliness is associated with heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, which can adversely affect spiritual well-being. Individuals grappling with loneliness often perceive a lack of social support and connection, leading to diminished self-esteem and amplified stress and anxiety [23].

Moreover, spiritual health encompasses a strong connection with oneself and others alongside an overarching sense of meaning and purpose. Consequently, loneliness may disrupt these important connections, undermining spiritual health. The reduction in social ties, integral to nurturing spiritual wellness, illustrates the detrimental impact of loneliness. Close relationships foster a sense of belonging and validation, crucial for emotional and spiritual enrichment. Thus, loneliness can precipitate stagnation in personal growth and engender feelings of worthlessness, which are detrimental to spiritual health. For instance, the emotional ramifications of loneliness may manifest as depression, anxiety, and a pervasive sense of dissatisfaction, all of which serve to compromise one’s spiritual health [24].

The findings of this study elucidate the interrelationship between loneliness and spiritual health, particularly in the context of older adults. Loneliness can result in a significant deprivation of meaningful interpersonal connections, adversely affecting individuals' emotional well-being and motivation. The experience of loneliness may contribute to heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, all of which can detrimentally impact one's spiritual health. Conversely, spiritual health encompasses meaningful relationships, a sense of purpose, and an overarching coherence in one’s life. In this regard, when older adults experience low levels of loneliness and cultivate positive, supportive connections, it may fortify their spiritual health and enhance their overall enjoyment of life [25].

Maintaining a constructive relationship with loneliness and promoting spiritual health is paramount for older adults. A deeper comprehension of the interplay between these factors can facilitate the identification of effective resources to enhance spiritual well-being, thereby mitigating feelings of loneliness [26].

Moreover, the results elucidate several pathways through which dysfunctional attitudes may adversely impact spiritual health. Firstly, the perpetuation of feelings of worthlessness can exacerbate restlessness, negatively affect self-confidence, and heighten stress levels, all disadvantageous to spiritual well-being. Secondly, individuals burdened by negative attitudes may find themselves struggling to navigate life's challenges, leading to heightened levels of depression and anxiety, ultimately compromising their spiritual health.

Additionally, such negative attitudes can diminish one's sense of satisfaction and happiness in life, which is intrinsically linked to spiritual well-being. Furthermore, the presence of dysfunctional attitudes has the potential to impede spiritual connections, subsequently reducing social support networks and fostering feelings of loneliness, which can further harm spiritual health.

It is important to note that this study faced certain limitations, particularly due to the unique circumstances surrounding the elderly population. These limitations include the challenge of generalizing findings to other diseases and patients residing in different locations or settings. Furthermore, the reliance on questionnaire-based data collection, coupled with the inherent tedium of questionnaire completion, is another limitation of this research. Consequently, it is recommended that future studies incorporate alternative methodologies, such as qualitative interviews, and explore the impact of the examined factors on a broader demographic.

This study's limitations include generalizability concerns, as it exclusively involved elderly participants from Tehran province, which may not reflect the experiences of elderly individuals in other regions. Data collection faced delays due to a lack of cooperation from some participants, leading to a slower process. Additionally, the physical and mental states of the elderly while completing the questionnaires could have influenced their responses, raising questions about data accuracy. The use of self-report instruments introduces potential bias, which is common in retrospective studies. Furthermore, the study did not account for cultural and social factors as predictors of death anxiety, focusing solely on psychological variables, which may have limited the understanding of the issue. Lastly, the possibility of participant fatigue from completing lengthy questionnaires could have negatively affected the data quality. Together, these limitations suggest a careful interpretation of the findings and highlight the need for further research that encompasses a broader range of factors.

The implications of this study underscore the critical importance of addressing spiritual health and psychological well-being in elderly populations, particularly in relation to death anxiety and loneliness. The findings suggest that care programs for the elderly should incorporate spiritual health initiatives and counseling methods to alleviate death anxiety, potentially enhancing their mental health outcomes. Additionally, fostering social support is crucial in combating loneliness and creating a sense of usefulness among elderly individuals. Future research is recommended to explore the impact of various mediating factors, such as education level and income, and to include a broader demographic, including those residing in nursing homes. Longitudinal and mixed-method approaches may yield valuable insights into the dynamics of death anxiety and its interplay with loneliness in different contexts. Overall, expanding studies to include diverse samples across various regions will contribute significantly to understanding and improving the lives of the elderly. Future research should explore holistic approaches that integrate spiritual practices and community support systems into mental health initiatives tailored for older adults. Such strategies may empower individuals to cope better with their mortality and cultivate a more fulfilling and meaningful late-life experience.

Conclusion

Enhancing spiritual health through strengthening perceived social support is a viable strategy to alleviate death anxiety among older adults. Addressing loneliness and fostering supportive social relationships can improve older adults' mental health and quality of life.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the participating older adults for their valuable contributions to this study. We also appreciate the support from Shahr-e-Rey Retirement Institution.

Ethical Permissions: The Research Ethics Committees of Tehran Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences approved this study (code of ethics: IR.IAU.TMU.REC.1403.042).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this research. There were no competing interests that could have influenced the outcomes of this study.

Authors' Contribution: Keyvan Nasab Sh (First Author), Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Hamid B (Second Author), Discussion Writer (20%); Ganji L (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Amini M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Pashmdarfard M (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Davari Z (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%)

Funding/Support: The authors declare that no financial support was received for the conduct of this study or the preparation of this manuscript. All research and writing efforts were conducted independently without external funding.

Death anxiety encompasses a range of thoughts, fears, and emotions associated with the concept of mortality [1]. Available literature, including comprehensive reviews of research undertaken in nonclinical populations, has shown that death anxiety is a prevalent phenomenon within the general population [2]. In late adulthood, individuals often become increasingly preoccupied with the concept of death, engaging in discussions about it more frequently. This heightened awareness is frequently prompted by observable physical changes, an uptick in illness and disability, and the bereavement of relatives and friends. While experiencing a certain degree of anxiety regarding death is normative, excessive manifestations of such anxiety may hinder psychological adjustment and functional capabilities. Notably, the predominant human response to death tends to be characterized by feelings of hatred, hostility, and disgust, which are often intermingled with fear. The intensity and expression of these emotions can differ significantly among individuals, influenced by temporal, racial, religious, and cultural contexts [3].

Another pertinent variable influencing individuals' mental health, particularly among older adults, is loneliness. Loneliness represents a profoundly distressing experience that can precipitate severe psychological and physical health issues [4]. Research has identified a correlation between loneliness and various adverse outcomes, including depression, suicidal tendencies, substance abuse, feelings of hopelessness, and aggravation of physical ailments [5]. Some scholars have conceptualized loneliness in terms of the discrepancy between desired and actual levels of social relationships, assessing both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. Thus, the experience of loneliness is underpinned by the gap between an individual’s aspirations regarding interpersonal connections and the reality of their existing relationships and intimacy. As this disparity increases, so too does the sensation of loneliness. Given the significant implications of loneliness for psychological and physical health, it is imperative to analyze the factors contributing to it [6].

Several factors contribute to loneliness among the elderly. A particularly salient variable is perceived social support. Researchers and experts in gerontology argue that the perception of social support is instrumental in mitigating the adverse physiological complications associated with various medical conditions in older adults. It can enhance levels of self-care and self-confidence, positively influencing older adults' physical, mental, and social well-being, thereby markedly improving their overall performance and quality of life [7].

In the context of older adults, perceived social support not only affects their psychological status but also plays a pivotal role in determining the severity of their medical conditions, which can subsequently impact their physical and mental health [8]. Empirical studies indicate that augmenting the perceived social support available to physically ill elderly patients can lead to a reduction in mortality rates and the severity of their illnesses. Furthermore, older adults with robust social support networks are observed to face a lower risk of disease progression and exhibit diminished psychological vulnerability [9].

Despite the recognized importance of perceived social support, there exists a notable paucity of research addressing its implications for loneliness, death anxiety, and quality of life for older adults. Consequently, an additional objective of the present study is to explain the role of perceived social support within this demographic [10].

Moreover, depression among older adults frequently correlates with the presence of dysfunctional attitudes [10]. According to Aaron Beck's theoretical framework, these dysfunctional attitudes represent enduring personality traits that predispose individuals to depressive disorders. They are characterized by negative cognitive schemas concerning the self, the world, and the future, often conceptualized as the negative cognitive triangle [11].

Historically, health has been delineated through specific dimensions encompassing physical, mental, and social well-being. Some scholars have advocated for the inclusion of spiritual health within this holistic model of health, prompting increased attention from policymakers and community health planners across various governmental entities. Research indicates that spiritual health is inextricably linked with other biological dimensions of an individual's life, thereby underscoring that achieving optimal quality of life necessitates the integration of these diverse health dimensions [12].

Spiritual health encompasses the individual's spiritual experiences from two distinct perspectives: The religious health perspective, which examines how individuals understand their health concerning a higher power, and the existential health perspective, which focuses on social and psychological concerns and how individuals adapt to their societal and environmental contexts. Diverse definitions of spiritual health exist. Some posit that spirituality is inherently derived from religious beliefs, leading to variations in definitions of spiritual health across different faiths. Factors such as life events, belief systems, religious practices, gender, and individual life stages significantly influence one's spirituality [13].

The Academy of Medical Sciences of Iran has articulated a definition of spiritual health, describing it as a dynamic state characterized by varying levels of insight, tendencies, and abilities that facilitate the elevation of the soul toward a connection with the Divine. This definition emphasizes the harmonious and balanced utilization of all internal capacities in

alignment with overarching spiritual goals, manifesting in internal and external behaviors reflecting this pursuit of connection with God, self, society, and nature [14].

This study aimed to investigate the correlation between loneliness, death anxiety, perceived social support, and spiritual health. A critical focus was placed on evaluating the mediating role of spiritual health in this relationship, aiming to clarify how it may serve as a buffer against the effects of loneliness and dysfunctional attitudes on death anxiety.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sampling

In this descriptive cross-sectional study, which lasted from May to July 2024, women aged 60 and above who were members of the Shahr-e Rey Retirement Institution of Tehran Province and lived in Tehran were invited to participate in volunteer through direct invitations. Any health condition or sudden event that disrupted the data collection process resulted in the participant's exclusion.

Considering the number of parameters, increasing statistical power, and managing potential participant dropouts [15], the sample size was calculated to be at least 384 individuals. Considering the total number of members at the Shahr-e Ray Retirement Center in Tehran Province was 1,322, the Cochran formula was applied, resulting in an estimated sample size of approximately 386.58 individuals. This was adjusted to account for possible dropouts, confirming a target sample size of 384 individuals. The same figure was ultimately reached in both approaches to determining the sample size. A convenience sampling method was employed to select participants.

Measures

Death Anxiety Scale (DAS): developed and validated by Templer in 1970, is one of the most widely utilized instruments for assessing death anxiety [16]. This self-administered questionnaire consists of 15 true-false questions to evaluate an individual's attitudes toward death. It operates within the dimensions of general anxiety, specific anxieties related to death, and fears surrounding surgical interventions. A 'yes' response indicates the presence of an anxiety-provoking factor in the individual, suggesting a level of psychological distress. The scoring on the DAS ranges from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater levels of death anxiety [16]. The test-retest validity of the Persian version of the DAS has been reported at 0.85, while the split-half reliability coefficient stands at 0.62. The overall reliability, as measured by Cronbach's alpha, is 0.73 [16]. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the 15 questions of the DAS was determined to be 0.78, indicating a consistent and reliable measure of death anxiety.

Revised Russell Loneliness Scale (R-RLS): developed by Russell et al., is a psychometric instrument comprising 20 items that utilize a 4-point Likert scale ranging from "never" (score of 1) to "always" (score of 4) [17]. The scale is evenly divided, containing 10 positively and 10 negatively framed items [17]. The overall score for the scale is calculated by summing the responses to all questions, yielding a total score that ranges from 20 to 80 [17].

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): was developed by Zimet et al. and comprises 12 items that are categorized into three distinct subscales: Social support received from family (four items), social support received from friends (four items), and social support received from significant others (four items) [18]. This scale assesses perceived social support from familial, friendly, and other significant relationships within an individual’s social network. The developers reported satisfactory validity and reliability for the MSPSS [18]. Similarly, Salimi & Bozorgpour demonstrated the reliability of the Persian version of the MSPSS, finding Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.86, 0.86, and 0.82 for the dimensions of social support received from family, friends, and significant others, respectively [19].

Dysfunctional Attitudes Questionnaire (DAQ): was developed by Weissman & Beck based on Beck's theory regarding the cognitive structure of depression [20]. This questionnaire consists of four subscales and 26 items; Achievement-perfectionism, the need for approval from others, the need to please others, and vulnerability to performance evaluation. Ebrahimi et al. have reported the internal consistency of the 26-item version of the DAQ using a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 [21].

Spiritual Health Assessment Scale (SHAS): The scale developed by Lata Gaur & Sharma comprises three distinct subscales and 21 items [22]. These subscales are categorized as follows: 1) self-growth, 2) self-actualization, and 3) self-realization. Each subscale is further delineated into seven specific components. The self-growth subscale encompasses the components of foresight, gratitude, generosity, charity, tolerance, self-control, and ethical behavior. The self-actualization subscale includes introspection, purpose in life, pathways in life, strengths, weaknesses, solutions, and considerations of the end of life. The self-realization subscale comprises recklessness, yoga, satisfaction, freedom, understanding of inner truths, happiness, and the sixth sense [22].

Procedure

After obtaining the ethical approval, data was collected by the trained individuals. Each participant completed all measures, and informed consent was obtained before they engaged with the questionnaires.

Data analysis

We utilized Pearson correlation coefficients to analyze the relationships between loneliness, perceived social support, death anxiety, spiritual

health, and death anxiety. We conducted path analysis to assess both the direct and indirect effects among the constructs. Several key criteria were assessed to evaluate model fit indices accurately. A chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio of less than 3 was considered acceptable, alongside other metrics such as the adaptive fit index, fitness index, and reduced fitness index, which should ideally be greater than or equal to 0.9. A square root of the approximation error of less than 0.08, coupled with a non-adaptive fit index exceeding 0.9, serves as additional indicators of model appropriateness.

All analyses were performed using SPSS 22 and AMOS 22 software at a significance level of p<0.05.

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 69.0±7.4 years. Most participants were female (59.0%), between 67 and 70 years old (42.6%), and with a high school diploma (37.5%; Table 1).

There were significant positive correlations between all the research parameters (p<0.001; Table 2).

Path analysis was used to examine the relationship between “feelings of loneliness”, “perceived social support”, “dysfunctional attitudes” and “death anxiety”, considering the mediating role of spiritual health (Table 3).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

Table 2. The correlation coefficient between research parameters (all significant at p<0.001)

Table 3. Path analysis results

There was a significant effect of loneliness on spiritual health, with a coefficient of 0.46. Furthermore, the effect of spiritual health on death anxiety was quantified at 0.79. Both of these effects achieved statistical significance at the 99% confidence level. The calculation of the indirect effect of loneliness on death anxiety, derived from the product of these coefficients (0.46×0.79), yielded an indirect effect of 0.36. The critical ratio for this indirect effect exceeded 2.57 (p<0.01), thereby supporting the conclusion that there existed a noteworthy relationship between loneliness and death anxiety that was mediated by spiritual health. However, it was pertinent to note that loneliness maintained a significant direct effect on death anxiety, suggesting that the role of spiritual health as a mediator was relatively minor.

Similarly, the analysis revealed that the coefficient representing the effect of perceived social support on spiritual health was 0.62. In contrast, the effect of spiritual health on death anxiety again stood at 0.79, with both effects being significant at the 99% confidence level. The indirect effect of perceived social support on death anxiety, calculated by multiplying these coefficients (0.62×0.79), resulted in an indirect effect of 0.48. The critical ratio for this indirect effect also surpassed 2.57 (p<0.01), reinforcing the presence of a significant relationship between perceived social support and death anxiety through spiritual health (Table 4).

Table 4. Total, direct, and indirect standard coefficients of the model

Discussion

This study sought to examine the relationship between loneliness, mental health, and dysfunctional attitudes while also examining the mediating role of spiritual health among community-dwelling elderly individuals. The findings reveal a significant correlation among cognitive components, including loneliness, dysfunctional attitudes, and perceived social support, alongside their impact on spiritual health. These results suggest that loneliness may adversely affect both mental and spiritual well-being. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of social connections and support in fostering spiritual health. Engagement in activities such as meditation, yoga, and creative expression is posited to mitigate feelings of loneliness and enhance spiritual well-being, thereby underscoring the multifaceted interplay between these variables in the elderly population.

In light of the findings from the present study, robust interpersonal connections, a profound sense of meaning and purpose in life, and experiences of coherence and personal growth all significantly contribute to an individual’s spiritual health. Conversely, the experience of loneliness is associated with heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, which can adversely affect spiritual well-being. Individuals grappling with loneliness often perceive a lack of social support and connection, leading to diminished self-esteem and amplified stress and anxiety [23].

Moreover, spiritual health encompasses a strong connection with oneself and others alongside an overarching sense of meaning and purpose. Consequently, loneliness may disrupt these important connections, undermining spiritual health. The reduction in social ties, integral to nurturing spiritual wellness, illustrates the detrimental impact of loneliness. Close relationships foster a sense of belonging and validation, crucial for emotional and spiritual enrichment. Thus, loneliness can precipitate stagnation in personal growth and engender feelings of worthlessness, which are detrimental to spiritual health. For instance, the emotional ramifications of loneliness may manifest as depression, anxiety, and a pervasive sense of dissatisfaction, all of which serve to compromise one’s spiritual health [24].

The findings of this study elucidate the interrelationship between loneliness and spiritual health, particularly in the context of older adults. Loneliness can result in a significant deprivation of meaningful interpersonal connections, adversely affecting individuals' emotional well-being and motivation. The experience of loneliness may contribute to heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, all of which can detrimentally impact one's spiritual health. Conversely, spiritual health encompasses meaningful relationships, a sense of purpose, and an overarching coherence in one’s life. In this regard, when older adults experience low levels of loneliness and cultivate positive, supportive connections, it may fortify their spiritual health and enhance their overall enjoyment of life [25].

Maintaining a constructive relationship with loneliness and promoting spiritual health is paramount for older adults. A deeper comprehension of the interplay between these factors can facilitate the identification of effective resources to enhance spiritual well-being, thereby mitigating feelings of loneliness [26].

Moreover, the results elucidate several pathways through which dysfunctional attitudes may adversely impact spiritual health. Firstly, the perpetuation of feelings of worthlessness can exacerbate restlessness, negatively affect self-confidence, and heighten stress levels, all disadvantageous to spiritual well-being. Secondly, individuals burdened by negative attitudes may find themselves struggling to navigate life's challenges, leading to heightened levels of depression and anxiety, ultimately compromising their spiritual health.

Additionally, such negative attitudes can diminish one's sense of satisfaction and happiness in life, which is intrinsically linked to spiritual well-being. Furthermore, the presence of dysfunctional attitudes has the potential to impede spiritual connections, subsequently reducing social support networks and fostering feelings of loneliness, which can further harm spiritual health.

It is important to note that this study faced certain limitations, particularly due to the unique circumstances surrounding the elderly population. These limitations include the challenge of generalizing findings to other diseases and patients residing in different locations or settings. Furthermore, the reliance on questionnaire-based data collection, coupled with the inherent tedium of questionnaire completion, is another limitation of this research. Consequently, it is recommended that future studies incorporate alternative methodologies, such as qualitative interviews, and explore the impact of the examined factors on a broader demographic.

This study's limitations include generalizability concerns, as it exclusively involved elderly participants from Tehran province, which may not reflect the experiences of elderly individuals in other regions. Data collection faced delays due to a lack of cooperation from some participants, leading to a slower process. Additionally, the physical and mental states of the elderly while completing the questionnaires could have influenced their responses, raising questions about data accuracy. The use of self-report instruments introduces potential bias, which is common in retrospective studies. Furthermore, the study did not account for cultural and social factors as predictors of death anxiety, focusing solely on psychological variables, which may have limited the understanding of the issue. Lastly, the possibility of participant fatigue from completing lengthy questionnaires could have negatively affected the data quality. Together, these limitations suggest a careful interpretation of the findings and highlight the need for further research that encompasses a broader range of factors.

The implications of this study underscore the critical importance of addressing spiritual health and psychological well-being in elderly populations, particularly in relation to death anxiety and loneliness. The findings suggest that care programs for the elderly should incorporate spiritual health initiatives and counseling methods to alleviate death anxiety, potentially enhancing their mental health outcomes. Additionally, fostering social support is crucial in combating loneliness and creating a sense of usefulness among elderly individuals. Future research is recommended to explore the impact of various mediating factors, such as education level and income, and to include a broader demographic, including those residing in nursing homes. Longitudinal and mixed-method approaches may yield valuable insights into the dynamics of death anxiety and its interplay with loneliness in different contexts. Overall, expanding studies to include diverse samples across various regions will contribute significantly to understanding and improving the lives of the elderly. Future research should explore holistic approaches that integrate spiritual practices and community support systems into mental health initiatives tailored for older adults. Such strategies may empower individuals to cope better with their mortality and cultivate a more fulfilling and meaningful late-life experience.

Conclusion

Enhancing spiritual health through strengthening perceived social support is a viable strategy to alleviate death anxiety among older adults. Addressing loneliness and fostering supportive social relationships can improve older adults' mental health and quality of life.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the participating older adults for their valuable contributions to this study. We also appreciate the support from Shahr-e-Rey Retirement Institution.

Ethical Permissions: The Research Ethics Committees of Tehran Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences approved this study (code of ethics: IR.IAU.TMU.REC.1403.042).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this research. There were no competing interests that could have influenced the outcomes of this study.

Authors' Contribution: Keyvan Nasab Sh (First Author), Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Hamid B (Second Author), Discussion Writer (20%); Ganji L (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (20%); Amini M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Pashmdarfard M (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (20%); Davari Z (Sixth Author), Assistant Researcher (5%)

Funding/Support: The authors declare that no financial support was received for the conduct of this study or the preparation of this manuscript. All research and writing efforts were conducted independently without external funding.

Keywords:

References

1. Shakeri B, Abdi K, Bagi M, Dalvand S, Shahriari H, Sadeghi S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of death anxiety among Iranian patients with cancer. Omega. 2024;89(1):247-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/00302228211070400]

2. Gürbüz A, Yorulmaz O. Death anxiety in psychopathology: A systematic review. Curr Approaches Psychiatry. 2024;16(1):159-74. [Link] [DOI:10.18863/pgy.1267748]

3. Fekih-Romdhane F, Malaeb D, Postigo A, Sakr F, Dabbous M, Khatib SE, et al. The relationship between climate change anxiety and psychotic experiences is mediated by death anxiety. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2024;70(3):574-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/00207640231221102]

4. Menzies RE, Menzies RG. Death anxiety and mental health: Requiem for a dreamer. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2023;78:101807. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2022.101807]

5. Soleimani MA, Bahrami N, Allen KA, Alimoradi Z. Death anxiety in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48: 101803. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101803]

6. Lin WH, Chiao C. Adverse adolescence experiences, feeling lonely across life stages and loneliness in adulthood. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2020;20(3):243-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.006]

7. Jefferson R, Barreto M, Verity L, Qualter P. Loneliness during the school years: How it affects learning and how schools can help. J Sch Health. 2023;93(5):428-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/josh.13306]

8. Wang S, Wu T, Liu J, Guan W. Relationship between perceived discrimination and social anxiety among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders in China: The mediating roles of affiliate stigma and perceived social support. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2024;111:102310. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102310]

9. Woods C, Richardson T, Palmer‐Cooper E. Are dysfunctional attitudes elevated and linked to mood in bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2024;63(1):16-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12442]

10. Fausor R, García-Vera MP, Moran N, Cobos B, Navarro R, Sánchez-Marqueses JM, et al. Depressive dysfunctional attitudes and post-traumatic stress in victims of terrorist attacks. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2023;32(3):430-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10926771.2022.2112341]

11. Rajabi R, Eslami Aliabadi H, Afrazandeh SS. Relationship between social support, dysfunctional attitude, and perceived academic stress in students of Ferdows school of medical sciences. J Med Educ Dev. 2024;16(52):75-83. [Link] [DOI:10.32592/jmed.2023.16.52.75]

12. Rahbar Karbasdehi E, Afrooz G A, Rahbar Karbasdehi F. The effect of family-based behavioral management program training on dysfunctional attitudes and psychological well-being in adolescents with a tendency towards drug use. Sci Q Res Addctn. 2024;18(71):85-102. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.61186/etiadpajohi.18.71.85]

13. Mensah GB, Addy A. Critical issues for regulating AI use in mental healthcare and medical negligence. 2023. [Link]

14. Olawade DB, Wada OZ, Odetayo A, David-Olawade AC, Asaolu F, Eberhardt J. Enhancing mental health with Artificial Intelligence: Current trends and future prospects. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;3:100099. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100099]

15. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. [Link]

16. Sharif Nia H, Ebadi A, Lehto RH, Mousavi B, Peyrovi H, Chan YH. Reliability and validity of the Persian version of templer death anxiety scale extended in veterans of Iran-Iraq warfare. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2014;8(4):29-37. [Link]

17. Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472-80. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472]

18. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess. 1988;52(1):30-41. [Link] [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2]

19. Salimi A, Bozorgpour F. Percieved social support and social-emotional loneliness. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;69:2009-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.158]

20. Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and validation of the dysfunctional attitude scale: A preliminary investigation. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse, 1978. [Link]

21. Ebrahimi A, Samouei R, Mousavii SG, Bornamanesh AR. Development and validation of a 26-item dysfunctional attitude scale. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5(2):101-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/appy.12020]

22. Lata Gaur K, Sharma M. Measuring spiritual health: Spiritual health assessment scale (SHAS). Int J Innov Res Dev. 2014;3(3):63-7. [Link]

23. Karahan M, Eliacik BK, Baydili KN. The interplay of spiritual health, resilience, and happiness: An evaluation among a group of dental students at a state university in Turkey. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):587. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12903-024-04297-4]

24. Lotfi MH, Faraz MM, Namiranian N, Arab R, Dashtabadi M, Khormizi HZ. A review about the role of spiritual health in type 2 diabetes mellitus people. Iran J Diabetes Obes. 2024;16(1):59-63. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/ijdo.v16i1.15243]

25. Rajabi R, Eslami Aliabadi H, Javad Mahdizadeh M, Azzizadeh Forouzi M. A comparative study of religious beliefs, spiritual intelligence and spiritual well-being in two therapies based on education (anonymous drug user) and methadone in drug user in Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2023;16(1):101. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13104-023-06377-0]

26. Oshvandi K, Torabi M, Khazaei M, Khazaei S, Yousofvand V. Impact of hope on stroke patients receiving a spiritual care program in Iran: A randomized controlled trial. J Relig Health. 2024;63(1):356-69. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10943-022-01696-1]