Volume 16, Issue 4 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(4): 333-339 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.302

History

Received: 2024/11/1 | Accepted: 2025/12/12 | Published: 2024/12/15

Received: 2024/11/1 | Accepted: 2025/12/12 | Published: 2024/12/15

How to cite this article

Mirzakhani Araghi N, Saei S, Mehri Mirza S, Pashmdarfard M, Aghapour E. Relationship between Suicidal Ideation, Mindfulness, and Sensory Processing Patterns in Soldiers. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (4) :333-339

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1520-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1520-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Rehabilitation Research Center” and “Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences”, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Social Welfare Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Rehabilitation Research Center” and “Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences”, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Tehran Central Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Social Welfare Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (704 Views)

Introduction

Military service, a mandatory phase for Iranian male citizens under conscription laws, marks a significant transitional period often characterized by unique psychological and environmental challenges [1]. This period introduces substantial changes in lifestyle, including alterations in nutrition, sleep, and personal autonomy, along with the need to adapt to a hierarchical and culturally diverse environment [2]. These changes, often abrupt and intense, can lead to an overwhelming sense of vulnerability and stress, potentially exacerbating underlying mental health conditions. The resulting stressors—stemming from interpersonal conflicts, demanding responsibilities, and feelings of isolation—can contribute to heightened anxiety and stress levels [3]. As soldiers confront these challenges, their ability to adapt and cope is critical in mitigating the risk of mental health issues. These stressors are significant risk factors for suicidal ideation, defined as thoughts or plans to end one’s life [4]. Global data highlight the alarmingly high rates of suicide among soldiers, particularly during the first year of service, underscoring the urgency of addressing this issue [2, 5]. The vulnerability of soldiers to suicidal ideation during this period demands immediate attention and effective interventions.

Mindfulness, the ability to remain present and aware of one’s internal and external experiences (including sensations, feelings, and thoughts) without judgment, has emerged as a potential protective factor against suicidal ideation [6]. This practice has gained considerable attention in clinical settings for its potential to enhance emotional well-being and psychological resilience. Research has consistently shown that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with improved emotional regulation, better coping strategies, and reduced psychological distress [7-9]. Furthermore, mindfulness interventions have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating suicidal thoughts by enhancing self-awareness and promoting adaptive coping mechanisms [10]. Thus, mindfulness serves as an important tool for soldiers, particularly in high-stress environments where emotional regulation can significantly impact mental health outcomes.

Another critical factor potentially influencing suicidal ideation is sensory processing, which refers to the way individuals perceive, process, and respond to sensory stimuli [11, 12]. Sensory processing patterns are categorized into four quadrants, namely sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration. Sensory seeking involves a preference for stimulating environments, which may be beneficial for stress relief but can lead to maladaptive behaviors if unchecked. Sensory avoiding reflects an effort to minimize sensory input, which may help prevent overstimulation but could also contribute to social withdrawal and isolation. Sensory sensitivity is characterized by heightened awareness of sensory stimuli, often linked to emotional reactivity and stress. Low registration denotes a reduced response to sensory stimuli, potentially leading to disengagement and detachment from the environment [13]. Disruptions in sensory processing, particularly in high-stress situations, can profoundly impact a soldier’s ability to maintain focus, adapt to changing environments, and regulate emotions effectively.

Research suggests that disruptions in sensory processing can negatively impact emotional regulation and increase vulnerability to mental health issues, including suicidal ideation [14, 15]. For example, individuals with sensory impairments, particularly auditory ones, have reported higher rates of suicidal thoughts compared to those without such impairments [16]. Additionally, studies indicate that sensory processing difficulties are associated with lower levels of mindfulness, as challenges in managing sensory input can hinder present-moment awareness [9, 17]. As such, the combined influence of sensory processing and mindfulness is crucial for understanding the full scope of psychological factors that contribute to suicidal ideation in military personnel.

Despite evidence linking mindfulness and sensory processing patterns to mental health, there is a lack of research exploring their combined influence on suicidal ideation, particularly in the high-stress context of military service. Previous studies have primarily focused on either mindfulness or sensory processing individually, leaving a significant gap in understanding their interplay in predicting suicidal ideation among soldiers.

This study aimed to explore the relationships between suicidal ideation, mindfulness, and sensory processing patterns-including sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration-in soldiers. By addressing a critical gap in the literature, the research offered a novel, integrative perspective by examining sensory quadrants alongside mindfulness. The findings provided valuable insights into the psychological and sensory contributors to suicidal ideation in a military context.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was done on 200 soldiers serving in military barracks in Tehran, Iran in 2023.

Participants

Participants were selected using a convenience sampling method, with the inclusion criteria specifying that they must have completed at least three months of military service, be 18 years of age or older, possess basic literacy skills, and provide informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria included soldiers who were away on missions or those who expressed unwillingness to continue their participation.

Sample size

The sample size of 200 soldiers was determined using G*Power 3.1 software, with a medium effect size (0.30), a significance level (α) set at 0.05, and a power (1-β) of 0.80, which suggested a minimum of 192 participants for detecting a true effect. To account for potential non-responses or incomplete data, 200 soldiers were selected for participation.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the researcher secured the necessary permissions from the university and military authorities. Soldiers in Tehran’s barracks were approached with a formal introduction letter and consent process. Participants who met the inclusion criteria provided written consent and completed the study’s questionnaires. Data collection was conducted in a single session at the military barracks in Tehran, Iran, during the winter of 2023, and participants completed the questionnaires independently under the supervision of the researcher.

Data collection tools

Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (AASP)

It is a self-report tool designed to assess individuals’ reactions to sensory stimuli. It consists of 60 items divided across four sensory processing quadrants, namely low registration, sensory seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoiding. These quadrants capture different sensory processing styles. Participants rate how often they experience each sensory event on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (almost never) to five (almost always). Scores for each quadrant range from 5 to 75 [18]. The Persian version of the AASP has shown strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.894 to 0.916, and excellent test-retest reliability, with sub-test reliability coefficients between 0.885 and 0.948 [19].

Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

Designed by Baer et al., this tool includes 39 items assessing five mindfulness subscales, including observation, description, acting with awareness, non-judgment, and non-reactivity. Participants rate their responses on a five-point Likert scale (one=never, five=always) [20]. The FFMQ has been shown to have good reliability and validity in previous studies, with a test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.80 in Iran [21].

Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI)

This tool contains 19 items evaluating the presence and intensity of suicidal thoughts over the week prior to assessment. Responses are rated on a three-point scale (0-2), yielding a total score range of 0 to 38. A score of 0-5 indicates low risk, 6-19 indicates high risk, and 20-38 indicates very high risk for suicide [22]. The BSSI has demonstrated strong reliability and validity, with Cronbach’s alpha reported as 0.95 in Iranian samples [23].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and questionnaire scores, including means and standard deviations. Multivariate regression analysis was employed to examine the predictive relationships between sensory processing quadrants (sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration), mindfulness facets (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reactivity), and suicidal ideation scores. The standardized beta coefficients were reported to evaluate the relative contribution of each predictor, with significance set at p<0.05. Multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF), ensuring that VIF values remained below 10. Model fit was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²) and adjusted R² to account for the predictors included in the model.

Findings

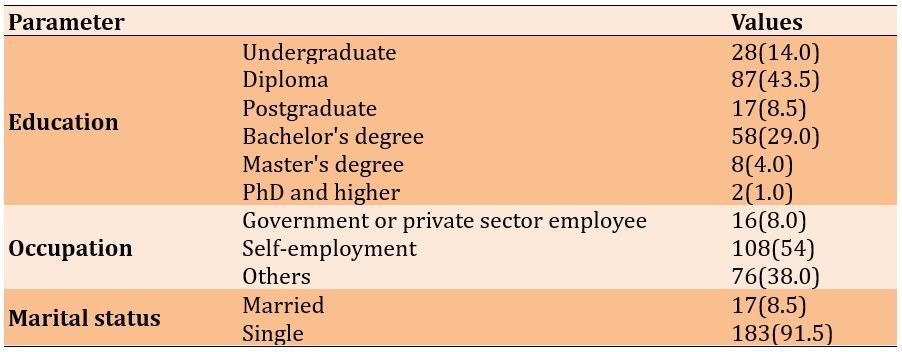

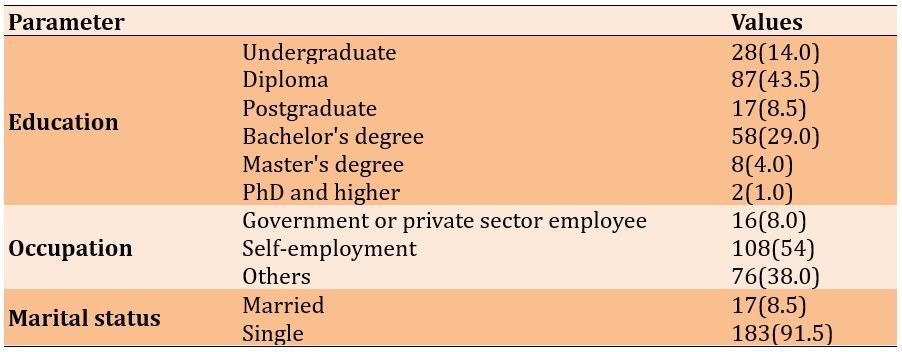

A total of 200 soldiers participated in the study, with a mean age of 23.3±3.3 years (Table 1). Most of the participants were unmarried (91.5%) and had varying educational backgrounds, with a significant proportion holding a diploma (43.5%) or a bachelor’s degree (29.0%). The majority of participants were self-employed (54%), while the remaining individuals were in either other job sectors (38%) or government/private sector employment (8%).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of soldiers

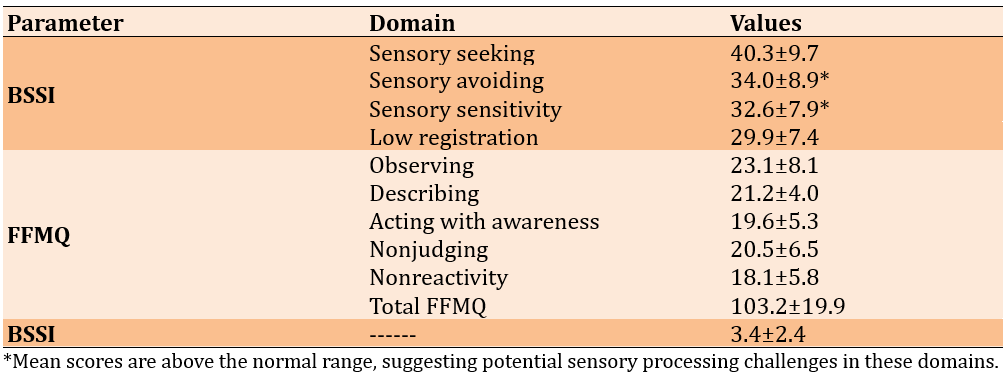

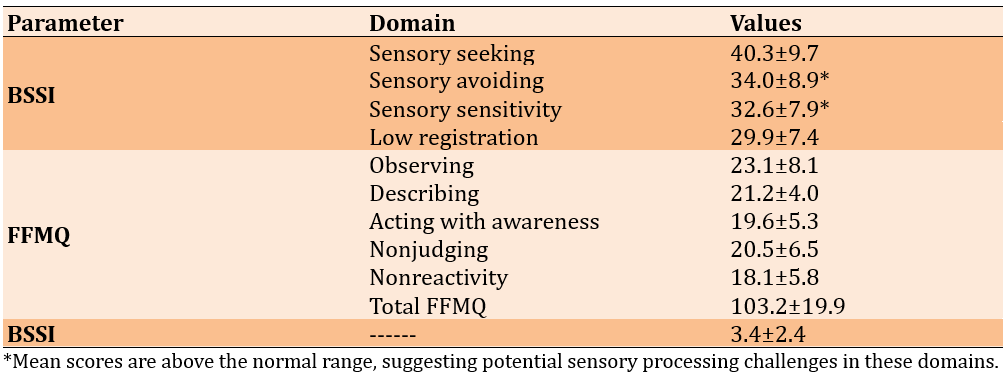

The mean scores for sensory avoidance and sensory sensitivity were above the normal range, indicating potential sensory processing challenges in these domains. Additionally, the average BSSI score in the study sample was 3.4±2.4, suggesting that participants were at low risk for suicidal ideation. For mindfulness, the participants’ total scores on the FFMQ ranged from 103.2±19.9, indicating a moderate level of mindfulness (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of the Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (AASP), the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), and the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) in participants

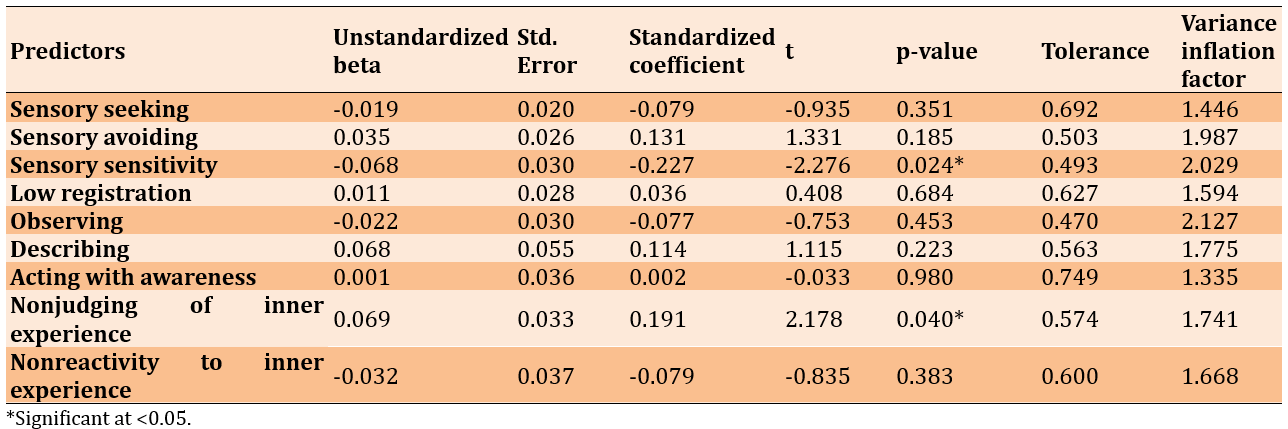

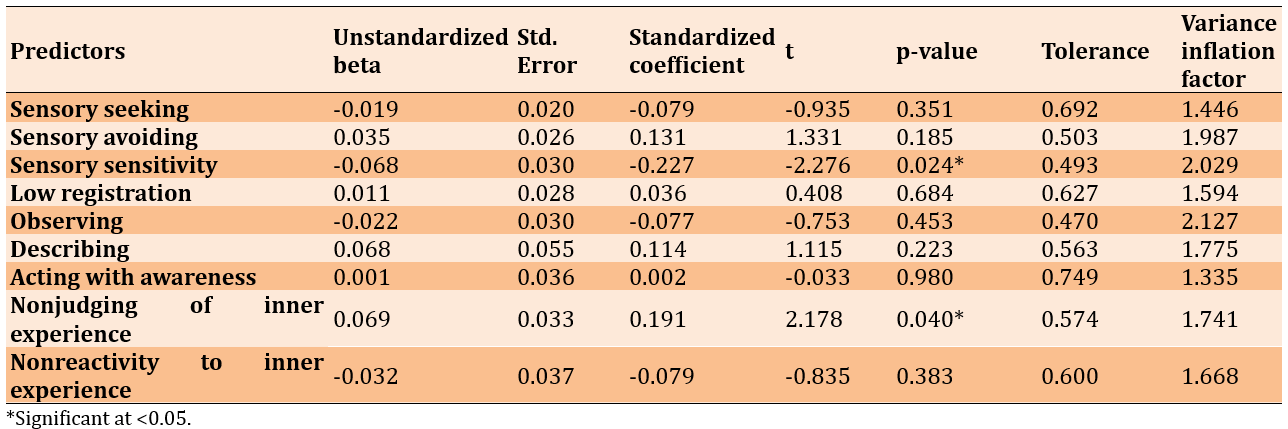

Sensory sensitivity and non-judging of inner experience were significant predictors of suicidal ideation. Specifically, higher sensory sensitivity scores were associated with lower levels of suicidal ideation, while higher non-judging scores were associated with increased suicidal ideation. Other sensory processing styles, including sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, and low registration, as well as mindfulness dimensions, such as observing, describing, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity, did not significantly predict suicidal ideation (Table 3).

The regression model explained a modest proportion of the variance in suicidal ideation (R²=0.071; adjusted R2=0.027). These findings suggest that while sensory processing and mindfulness factors contribute to suicidal ideation, additional unmeasured parameters may also play a role.

Table 3. Results of multivariate regression analysis on entry style to predict suicidal ideation through sensory processing quadrants and mindfulness aspects

Discussion

This study explored the relationships between suicidal ideation, mindfulness, and sensory processing patterns in soldiers, focusing on how sensory sensitivity and mindfulness dimensions predict suicidal thoughts. Our results provided valuable insights into how psychological and sensory factors contribute to suicidal ideation in the military context, an environment known for its unique stressors. Sensory sensitivity and the non-judging facets of mindfulness significantly influence suicidal ideation, while other sensory processing patterns and mindfulness components were not significant predictors.

Sensory sensitivity predicted lower suicidal ideation, which aligns with previous studies showing that heightened sensory sensitivity, often characterized by emotional reactivity to sensory input, is associated with higher emotional distress [24, 25]. Research has demonstrated that individuals with high sensory sensitivity may experience overwhelming emotional reactions, increasing their vulnerability to mental health challenges, including suicidal ideation [11, 26]. This finding is consistent with the study by Dunn, who suggests that individuals with sensory sensitivities may struggle with emotional regulation, potentially heightening their risk of mental health issues [27]. However, it is important to note that sensory sensitivity alone does not directly lead to suicidal ideation; instead, it may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities or interact with other factors, such as mindfulness, to contribute to suicidal thoughts. Additionally, the finding that higher sensory sensitivity was associated with lower suicidal ideation may appear counterintuitive at first glance. However, one possible explanation for this could be the adaptive coping mechanisms developed by highly sensitive individuals, which may allow them to process emotional stimuli in a way that ultimately reduces their suicidal thoughts. Future studies might explore whether coping strategies mediate the relationship between sensory sensitivity and suicidal ideation.

The non-judging facet of mindfulness was found to significantly predict increased suicidal ideation, which is consistent with studies suggesting that non-judging, a component of mindfulness, may be linked to negative emotional outcomes when not properly managed [28, 29]. Non-judging involves accepting internal experiences, such as emotions and thoughts, without evaluation. While non-judging can enhance emotional regulation when practiced effectively, its presence without sufficient awareness of how to process distressing emotions may lead to maladaptive patterns, such as rumination or emotional suppression, which could exacerbate suicidal thoughts [30, 31]. The finding that non-judging was associated with greater suicidal ideation aligns with research by Weber, who noted that mindfulness practices need to be coupled with a capacity for emotional awareness and regulation, rather than just non-judging, to achieve a positive outcome [32].

In contrast, other sensory processing patterns, such as sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, and low registration, were not significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Previous studies have shown that sensory seeking can be a protective factor in alleviating stress by providing stimulation [33, 34]; however, no direct link to suicidal ideation was found. This result is somewhat consistent with findings by Oppenheimer et al., which suggest that sensory-seeking behaviors can be a form of self-regulation to manage distress but do not directly mitigate or contribute to suicidal thoughts [35]. Similarly, sensory-avoiding behaviors, which aim to minimize overwhelming sensory input, did not predict suicidal ideation. It is possible that sensory avoiding, which can promote withdrawal or isolation, does not necessarily lead to suicidal ideation unless combined with other risk factors, such as poor emotional regulation. Earlier studies by Smith & Sharp found that sensory avoidance behaviors can exacerbate feelings of isolation and depression [36]; however, the results of this study do not support a direct link to suicidal ideation in soldiers.

Mindfulness, more generally, was also a significant predictor of suicidal ideation. Studies on mindfulness have consistently shown that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with decreased emotional distress and suicidal ideation [37]. Our findings reinforce the literature indicating that mindfulness, particularly components like non-judging, may provide insight into emotional regulation challenges among soldiers. However, mindfulness alone may not be sufficient to prevent suicidal ideation, especially when other factors, such as sensory processing or social support, are not adequately addressed.

One of the notable results of our study is the modest explanatory power of the regression model, indicating that while sensory processing and mindfulness components play a role in understanding suicidal ideation, they account for only a small portion of the variance in suicidal ideation. This suggests the presence of other unmeasured parameters (such as social support, life stress, or trauma exposure) that likely contribute to the complexity of suicidal thoughts among soldiers. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of contextual and environmental factors in influencing mental health outcomes, particularly in high-stress environments like military service [38, 39]. It is crucial to consider how broader life stressors, such as interpersonal relationships, military-specific challenges, and a history of trauma, may interact with mindfulness and sensory processing patterns to influence suicidal ideation.

In comparison to other studies, the prevalence of suicidal ideation in the current sample was relatively low. This contrasts with research in other military populations, where rates of suicidal ideation have been much higher, particularly among those in their first year of service [5]. However, given the cross-sectional design of this study, the observed relationships cannot be interpreted as causal, and longitudinal research is necessary to determine the directionality and long-term effects of sensory processing and mindfulness on suicidal ideation.

Despite these valuable findings, this study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design prevents conclusions about causality or the directionality of the relationships between sensory processing, mindfulness, and suicidal ideation. Self-report measures may introduce response biases. The sample was limited to soldiers, which affects the generalizability of the results. Additionally, factors such as social support, trauma history, and clinical diagnoses were not included; future research should incorporate these parameters to provide a more comprehensive understanding of suicidal ideation. In conclusion, the findings from this study offer a unique contribution to understanding the complex relationship between sensory processing patterns, mindfulness, and suicidal ideation in soldiers. Future research should investigate additional psychological, social, and environmental factors that may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the risk factors for suicidal ideation in military personnel.

Conclusion

Sensory sensitivity and the non-judging facet of mindfulness predict suicidal ideation among soldiers.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to the participants for their valuable contributions to this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti Medical University (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.302).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Mirzakhani Araghi N (First Author), Main Researcher (25%); Saei Sh (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Mehri Mirza S (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (20%); Pashmdarfard M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Aghapour E (Fifth Author), Methodologist (10%)

Funding/Support: There is nothing to be declared.

Military service, a mandatory phase for Iranian male citizens under conscription laws, marks a significant transitional period often characterized by unique psychological and environmental challenges [1]. This period introduces substantial changes in lifestyle, including alterations in nutrition, sleep, and personal autonomy, along with the need to adapt to a hierarchical and culturally diverse environment [2]. These changes, often abrupt and intense, can lead to an overwhelming sense of vulnerability and stress, potentially exacerbating underlying mental health conditions. The resulting stressors—stemming from interpersonal conflicts, demanding responsibilities, and feelings of isolation—can contribute to heightened anxiety and stress levels [3]. As soldiers confront these challenges, their ability to adapt and cope is critical in mitigating the risk of mental health issues. These stressors are significant risk factors for suicidal ideation, defined as thoughts or plans to end one’s life [4]. Global data highlight the alarmingly high rates of suicide among soldiers, particularly during the first year of service, underscoring the urgency of addressing this issue [2, 5]. The vulnerability of soldiers to suicidal ideation during this period demands immediate attention and effective interventions.

Mindfulness, the ability to remain present and aware of one’s internal and external experiences (including sensations, feelings, and thoughts) without judgment, has emerged as a potential protective factor against suicidal ideation [6]. This practice has gained considerable attention in clinical settings for its potential to enhance emotional well-being and psychological resilience. Research has consistently shown that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with improved emotional regulation, better coping strategies, and reduced psychological distress [7-9]. Furthermore, mindfulness interventions have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating suicidal thoughts by enhancing self-awareness and promoting adaptive coping mechanisms [10]. Thus, mindfulness serves as an important tool for soldiers, particularly in high-stress environments where emotional regulation can significantly impact mental health outcomes.

Another critical factor potentially influencing suicidal ideation is sensory processing, which refers to the way individuals perceive, process, and respond to sensory stimuli [11, 12]. Sensory processing patterns are categorized into four quadrants, namely sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration. Sensory seeking involves a preference for stimulating environments, which may be beneficial for stress relief but can lead to maladaptive behaviors if unchecked. Sensory avoiding reflects an effort to minimize sensory input, which may help prevent overstimulation but could also contribute to social withdrawal and isolation. Sensory sensitivity is characterized by heightened awareness of sensory stimuli, often linked to emotional reactivity and stress. Low registration denotes a reduced response to sensory stimuli, potentially leading to disengagement and detachment from the environment [13]. Disruptions in sensory processing, particularly in high-stress situations, can profoundly impact a soldier’s ability to maintain focus, adapt to changing environments, and regulate emotions effectively.

Research suggests that disruptions in sensory processing can negatively impact emotional regulation and increase vulnerability to mental health issues, including suicidal ideation [14, 15]. For example, individuals with sensory impairments, particularly auditory ones, have reported higher rates of suicidal thoughts compared to those without such impairments [16]. Additionally, studies indicate that sensory processing difficulties are associated with lower levels of mindfulness, as challenges in managing sensory input can hinder present-moment awareness [9, 17]. As such, the combined influence of sensory processing and mindfulness is crucial for understanding the full scope of psychological factors that contribute to suicidal ideation in military personnel.

Despite evidence linking mindfulness and sensory processing patterns to mental health, there is a lack of research exploring their combined influence on suicidal ideation, particularly in the high-stress context of military service. Previous studies have primarily focused on either mindfulness or sensory processing individually, leaving a significant gap in understanding their interplay in predicting suicidal ideation among soldiers.

This study aimed to explore the relationships between suicidal ideation, mindfulness, and sensory processing patterns-including sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration-in soldiers. By addressing a critical gap in the literature, the research offered a novel, integrative perspective by examining sensory quadrants alongside mindfulness. The findings provided valuable insights into the psychological and sensory contributors to suicidal ideation in a military context.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was done on 200 soldiers serving in military barracks in Tehran, Iran in 2023.

Participants

Participants were selected using a convenience sampling method, with the inclusion criteria specifying that they must have completed at least three months of military service, be 18 years of age or older, possess basic literacy skills, and provide informed consent to participate. Exclusion criteria included soldiers who were away on missions or those who expressed unwillingness to continue their participation.

Sample size

The sample size of 200 soldiers was determined using G*Power 3.1 software, with a medium effect size (0.30), a significance level (α) set at 0.05, and a power (1-β) of 0.80, which suggested a minimum of 192 participants for detecting a true effect. To account for potential non-responses or incomplete data, 200 soldiers were selected for participation.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the researcher secured the necessary permissions from the university and military authorities. Soldiers in Tehran’s barracks were approached with a formal introduction letter and consent process. Participants who met the inclusion criteria provided written consent and completed the study’s questionnaires. Data collection was conducted in a single session at the military barracks in Tehran, Iran, during the winter of 2023, and participants completed the questionnaires independently under the supervision of the researcher.

Data collection tools

Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (AASP)

It is a self-report tool designed to assess individuals’ reactions to sensory stimuli. It consists of 60 items divided across four sensory processing quadrants, namely low registration, sensory seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoiding. These quadrants capture different sensory processing styles. Participants rate how often they experience each sensory event on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (almost never) to five (almost always). Scores for each quadrant range from 5 to 75 [18]. The Persian version of the AASP has shown strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.894 to 0.916, and excellent test-retest reliability, with sub-test reliability coefficients between 0.885 and 0.948 [19].

Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

Designed by Baer et al., this tool includes 39 items assessing five mindfulness subscales, including observation, description, acting with awareness, non-judgment, and non-reactivity. Participants rate their responses on a five-point Likert scale (one=never, five=always) [20]. The FFMQ has been shown to have good reliability and validity in previous studies, with a test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.80 in Iran [21].

Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI)

This tool contains 19 items evaluating the presence and intensity of suicidal thoughts over the week prior to assessment. Responses are rated on a three-point scale (0-2), yielding a total score range of 0 to 38. A score of 0-5 indicates low risk, 6-19 indicates high risk, and 20-38 indicates very high risk for suicide [22]. The BSSI has demonstrated strong reliability and validity, with Cronbach’s alpha reported as 0.95 in Iranian samples [23].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and questionnaire scores, including means and standard deviations. Multivariate regression analysis was employed to examine the predictive relationships between sensory processing quadrants (sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration), mindfulness facets (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reactivity), and suicidal ideation scores. The standardized beta coefficients were reported to evaluate the relative contribution of each predictor, with significance set at p<0.05. Multicollinearity was assessed using tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF), ensuring that VIF values remained below 10. Model fit was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²) and adjusted R² to account for the predictors included in the model.

Findings

A total of 200 soldiers participated in the study, with a mean age of 23.3±3.3 years (Table 1). Most of the participants were unmarried (91.5%) and had varying educational backgrounds, with a significant proportion holding a diploma (43.5%) or a bachelor’s degree (29.0%). The majority of participants were self-employed (54%), while the remaining individuals were in either other job sectors (38%) or government/private sector employment (8%).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic characteristics of soldiers

The mean scores for sensory avoidance and sensory sensitivity were above the normal range, indicating potential sensory processing challenges in these domains. Additionally, the average BSSI score in the study sample was 3.4±2.4, suggesting that participants were at low risk for suicidal ideation. For mindfulness, the participants’ total scores on the FFMQ ranged from 103.2±19.9, indicating a moderate level of mindfulness (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of the Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (AASP), the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), and the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) in participants

Sensory sensitivity and non-judging of inner experience were significant predictors of suicidal ideation. Specifically, higher sensory sensitivity scores were associated with lower levels of suicidal ideation, while higher non-judging scores were associated with increased suicidal ideation. Other sensory processing styles, including sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, and low registration, as well as mindfulness dimensions, such as observing, describing, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity, did not significantly predict suicidal ideation (Table 3).

The regression model explained a modest proportion of the variance in suicidal ideation (R²=0.071; adjusted R2=0.027). These findings suggest that while sensory processing and mindfulness factors contribute to suicidal ideation, additional unmeasured parameters may also play a role.

Table 3. Results of multivariate regression analysis on entry style to predict suicidal ideation through sensory processing quadrants and mindfulness aspects

Discussion

This study explored the relationships between suicidal ideation, mindfulness, and sensory processing patterns in soldiers, focusing on how sensory sensitivity and mindfulness dimensions predict suicidal thoughts. Our results provided valuable insights into how psychological and sensory factors contribute to suicidal ideation in the military context, an environment known for its unique stressors. Sensory sensitivity and the non-judging facets of mindfulness significantly influence suicidal ideation, while other sensory processing patterns and mindfulness components were not significant predictors.

Sensory sensitivity predicted lower suicidal ideation, which aligns with previous studies showing that heightened sensory sensitivity, often characterized by emotional reactivity to sensory input, is associated with higher emotional distress [24, 25]. Research has demonstrated that individuals with high sensory sensitivity may experience overwhelming emotional reactions, increasing their vulnerability to mental health challenges, including suicidal ideation [11, 26]. This finding is consistent with the study by Dunn, who suggests that individuals with sensory sensitivities may struggle with emotional regulation, potentially heightening their risk of mental health issues [27]. However, it is important to note that sensory sensitivity alone does not directly lead to suicidal ideation; instead, it may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities or interact with other factors, such as mindfulness, to contribute to suicidal thoughts. Additionally, the finding that higher sensory sensitivity was associated with lower suicidal ideation may appear counterintuitive at first glance. However, one possible explanation for this could be the adaptive coping mechanisms developed by highly sensitive individuals, which may allow them to process emotional stimuli in a way that ultimately reduces their suicidal thoughts. Future studies might explore whether coping strategies mediate the relationship between sensory sensitivity and suicidal ideation.

The non-judging facet of mindfulness was found to significantly predict increased suicidal ideation, which is consistent with studies suggesting that non-judging, a component of mindfulness, may be linked to negative emotional outcomes when not properly managed [28, 29]. Non-judging involves accepting internal experiences, such as emotions and thoughts, without evaluation. While non-judging can enhance emotional regulation when practiced effectively, its presence without sufficient awareness of how to process distressing emotions may lead to maladaptive patterns, such as rumination or emotional suppression, which could exacerbate suicidal thoughts [30, 31]. The finding that non-judging was associated with greater suicidal ideation aligns with research by Weber, who noted that mindfulness practices need to be coupled with a capacity for emotional awareness and regulation, rather than just non-judging, to achieve a positive outcome [32].

In contrast, other sensory processing patterns, such as sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, and low registration, were not significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Previous studies have shown that sensory seeking can be a protective factor in alleviating stress by providing stimulation [33, 34]; however, no direct link to suicidal ideation was found. This result is somewhat consistent with findings by Oppenheimer et al., which suggest that sensory-seeking behaviors can be a form of self-regulation to manage distress but do not directly mitigate or contribute to suicidal thoughts [35]. Similarly, sensory-avoiding behaviors, which aim to minimize overwhelming sensory input, did not predict suicidal ideation. It is possible that sensory avoiding, which can promote withdrawal or isolation, does not necessarily lead to suicidal ideation unless combined with other risk factors, such as poor emotional regulation. Earlier studies by Smith & Sharp found that sensory avoidance behaviors can exacerbate feelings of isolation and depression [36]; however, the results of this study do not support a direct link to suicidal ideation in soldiers.

Mindfulness, more generally, was also a significant predictor of suicidal ideation. Studies on mindfulness have consistently shown that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with decreased emotional distress and suicidal ideation [37]. Our findings reinforce the literature indicating that mindfulness, particularly components like non-judging, may provide insight into emotional regulation challenges among soldiers. However, mindfulness alone may not be sufficient to prevent suicidal ideation, especially when other factors, such as sensory processing or social support, are not adequately addressed.

One of the notable results of our study is the modest explanatory power of the regression model, indicating that while sensory processing and mindfulness components play a role in understanding suicidal ideation, they account for only a small portion of the variance in suicidal ideation. This suggests the presence of other unmeasured parameters (such as social support, life stress, or trauma exposure) that likely contribute to the complexity of suicidal thoughts among soldiers. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of contextual and environmental factors in influencing mental health outcomes, particularly in high-stress environments like military service [38, 39]. It is crucial to consider how broader life stressors, such as interpersonal relationships, military-specific challenges, and a history of trauma, may interact with mindfulness and sensory processing patterns to influence suicidal ideation.

In comparison to other studies, the prevalence of suicidal ideation in the current sample was relatively low. This contrasts with research in other military populations, where rates of suicidal ideation have been much higher, particularly among those in their first year of service [5]. However, given the cross-sectional design of this study, the observed relationships cannot be interpreted as causal, and longitudinal research is necessary to determine the directionality and long-term effects of sensory processing and mindfulness on suicidal ideation.

Despite these valuable findings, this study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design prevents conclusions about causality or the directionality of the relationships between sensory processing, mindfulness, and suicidal ideation. Self-report measures may introduce response biases. The sample was limited to soldiers, which affects the generalizability of the results. Additionally, factors such as social support, trauma history, and clinical diagnoses were not included; future research should incorporate these parameters to provide a more comprehensive understanding of suicidal ideation. In conclusion, the findings from this study offer a unique contribution to understanding the complex relationship between sensory processing patterns, mindfulness, and suicidal ideation in soldiers. Future research should investigate additional psychological, social, and environmental factors that may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the risk factors for suicidal ideation in military personnel.

Conclusion

Sensory sensitivity and the non-judging facet of mindfulness predict suicidal ideation among soldiers.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to the participants for their valuable contributions to this study.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti Medical University (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.302).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Mirzakhani Araghi N (First Author), Main Researcher (25%); Saei Sh (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (30%); Mehri Mirza S (Third Author), Statistical Analyst (20%); Pashmdarfard M (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Aghapour E (Fifth Author), Methodologist (10%)

Funding/Support: There is nothing to be declared.

Keywords:

References

1. Soltaninejad A, Fathi-Ashtiani A, Ahmadi K, Mirsharafoddini HS, Nikmorad A, Pilevarzadeh M. Personality factors underlying suicidal behavior among military youth. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(4):e12686. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.12686]

2. Nouri R, Fathi-Ashtiani A, Salimi S, Soltani Nejad A. Effective factors of suicide in soldiers of a military force. Iran J Mil Med. 2012;14(2):99-103. [Link]

3. Orasanu JM, Backer P. Stress and military performance. In: Stress and human performance. Hove: Psychology Press; 2013. p. 89-125. [Link]

4. Defayette AB, Esposito‐Smythers C, Cero I, Kleiman EM, López Jr R, Harris KM, et al. Examination of proinflammatory activity as a moderator of the relation between momentary interpersonal stress and suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(6):922-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/sltb.12993]

5. Leah S, Eyal G, Nirit Y, Ariel BY, Yossi LB. Suicide among Ethiopian origin soldiers in the IDF-A qualitative view of risk factors, triggers, and life circumstances. J Affect Disord. 2020;269:125-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.034]

6. Damirchi ES, Samadifard HR. The role of irrational beliefs, mindfulness and cognitive avoidance in the prediction of suicidal thoughts in soldiers. J Mil Med. 2018;20(4):431-8. [Persian] [Link]

7. Schmelefske E, Per M, Khoury B, Heath N. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on suicide outcomes: A meta-analysis. Arch Suicide Res. 2022;26(2):447-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13811118.2020.1833796]

8. Luoma JB, Villatte JL. Mindfulness in the treatment of suicidal individuals. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):265-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.12.003]

9. Hebert KR. The association between sensory processing styles and mindfulness. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79(9):557-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0308022616656872]

10. Cho AS. Suicide and non-suicidal self injury: Art therapy and mindfulness techniques in a school setting to help decrease levels of anxiety, depression, and stress in adolescents [dissertation]. Chicago: The Chicago School of Professional Psychology; 2016. [Link]

11. Wyller HB, Wyller VBB, Crane C, Gjelsvik B. The relationship between sensory processing sensitivity and psychological distress: A model of underpinning mechanisms and an analysis of therapeutic possibilities. Scand Psychol. 2017;4(9). [Link] [DOI:10.15714/scandpsychol.4.e15]

12. Gómez RG. Identification of electroencephalography and psychophysical parameters with potential diagnostic use for suicidal patients [dissertation]. Chile: Pontifical Catholic University of Chile; 2023. [Link]

13. Mirzakhani Araghi N, Pashazadeh Azari Z, Alizadeh Zarei M, Akbarzadeh Baghban A, Saei S, Yousefi Nodeh HR, et al. The relationship between sensory processing patterns and participation in childhood leisure and play activities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran Rehabil J. 2023;21(1):17-38. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/irj.21.1.1277.2]

14. Benarous X, Bury V, Lahaye H, Desrosiers L, Cohen D, Guilé JM. Sensory processing difficulties in youths with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:164. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00164]

15. Serafini G, Gonda X, Canepa G, Pompili M, Rihmer Z, Amore M, et al. Extreme sensory processing patterns show a complex association with depression, and impulsivity, alexithymia, and hopelessness. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:249-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.019]

16. Turner O, Windfuhr K, Kapur N. Suicide in deaf populations: A literature review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6:26. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1744-859X-6-26]

17. Finck C, Avila A, Jiménez-Leal W, Botero JP, Shambo D, Hernandez S, et al. A multisensory mindfulness experience: Exploring the promotion of sensory awareness as a mindfulness practice. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1230832. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1230832]

18. Brown C. Adolescent/adult sensory profile. In: Assessments in occupational therapy mental health. London: Routledge; 2024. p. 445-56. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9781003522645-33]

19. Zaree M, Hassani Mehraban A, Lajevardi L, Saneii S, Pashazadeh Azari Z, Mohammadian Rasnani F. Translation, reliability and validity of Persian version of adolescent/adult sensory profile in dementia. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2023;30(1):1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/23279095.2021.1904927]

20. Baer R, Gu J, Strauss C. Five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). In: Handbook of assessment in mindfulness research. Cham: Springer; 2022. p. 1-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-77644-2_15-1]

21. Hashemi R, Moustafa AA, Rahmati Kankat L, Valikhani A. Mindfulness and suicide ideation in Iranian cardiovascular patients: Testing the mediating role of patience. Psychol Rep. 2018;121(6):1037-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0033294117746990]

22. Ghasemi P, Shaghaghi A, Allahverdipour H. Measurement scales of suicidal ideation and attitudes: A systematic review article. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5(3):156-68. [Link] [DOI:10.15171/hpp.2015.019]

23. Esfahani M, Hashemi Y, Alavi K. Psychometric assessment of beck scale for suicidal ideation (BSSI) in general population in Tehran. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:268. [Link]

24. Aron EN, Aron A, Jagiellowicz J. Sensory processing sensitivity: A review in the light of the evolution of biological responsivity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2012;16(3):262-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1088868311434213]

25. Meyer B, Ajchenbrenner M, Bowles DP. Sensory sensitivity, attachment experiences, and rejection responses among adults with borderline and avoidant features. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(6):641-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1521/pedi.2005.19.6.641]

26. Khodabakhsh S. Effects of sensory processing intervention on depression and anxiety among international students in a public university [dissertation]. Malaysia: University of Malaya; 2016. [Link]

27. Dunn W. The sensations of everyday life: Empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(6):608-20. [Link] [DOI:10.5014/ajot.55.6.608]

28. Wahbeh H, Lu M, Oken B. Mindful awareness and non-judging in relation to posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Mindfulness. 2011;2(4):219-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12671-011-0064-3]

29. Cherry M. Decreasing stress through an emotion regulation and non-judging based intervention with trauma-exposed college students [dissertation]. Ruston: Louisiana Tech University; 2019. [Link]

30. Jovaišaitė B. The link between mindfulness and psychological resilience among adult populations [dissertation]. Lithuania: Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Research Management System; 2024. [Link]

31. Chiang HN, Medvedev ON, Ponder WN, Carbajal J, Vujanovic AA. Network of mindfulness and difficulties in regulating emotions in firefighters. Mindfulness. 2024;15:1315-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s12671-024-02348-z]

32. Weber J. Mindfulness is not enough: Why equanimity holds the key to compassion. Mindfulness Compassion. 2017;2(2):149-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mincom.2017.09.004]

33. Roberti JW. A review of behavioral and biological correlates of sensation seeking. J Res Personal. 2004;38(3):256-79. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00067-9]

34. Araghi NM, Asghari A, Mahmoudi E, Saei S. The predictor effect and relationship between brain-behavioral systems, cognitive flexibility, sensory processing and anxiety in Iranian immigrant students in Canada. Middle East J Rehabil Health Stud. 2024;11(3):e137243. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/mejrh-137243]

35. Oppenheimer CW, Bertocci M, Greenberg T, Chase HW, Stiffler R, Aslam HA, et al. Informing the study of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in distressed young adults: The use of a machine learning approach to identify neuroimaging, psychiatric, behavioral, and demographic correlates. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2021;317:111386. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2021.111386]

36. Smith RS, Sharp J. Fascination and isolation: A grounded theory exploration of unusual sensory experiences in adults with Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(4):891-910. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10803-012-1633-6]

37. Anastasiades MH, Kapoor S, Wootten J, Lamis DA. Perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in undergraduate women with varying levels of mindfulness. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(1):129-38. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00737-016-0686-5]

38. Kavanagh J. Stress and performance: A review of the literature and its applicability to the military. Santa Monica: Rand; 2005. [Link]

39. Langston V, Gould M, Greenberg N. Culture: What is its effect on stress in the military?. Mil Med. 2007;172(9):931-5. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED.172.9.931]