Volume 16, Issue 3 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(3): 295-300 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/09/9 | Accepted: 2024/10/15 | Published: 2024/11/1

Received: 2024/09/9 | Accepted: 2024/10/15 | Published: 2024/11/1

How to cite this article

Noori T, Chiad I, Taqi F, Sabah H. Knowledge of Health & Medical Technologies’ Students about Herpes Zoster Virus. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (3) :295-300

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1507-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1507-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Community Health, Faculty of College of Health and Medical Technologies, Middle Technical University, Baghdad, Iraq

2- Department of Community Health, Faculty of Technical Medical Institute, Northern Technical University, Mousl, Iraq

2- Department of Community Health, Faculty of Technical Medical Institute, Northern Technical University, Mousl, Iraq

Full-Text (HTML) (562 Views)

Introduction

Herpes zoster (HZ), commonly called shingles, is a highly contagious condition caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). This virus remains latent within the cranial sensory and spinal ganglia after an individual has had an initial varicella (chickenpox) infection, typically occurring during childhood or adolescence [1, 2]. As a result, HZ only occurs in individuals previously infected with chickenpox [3].

The clinical presentation of HZ primarily involves a dermatological rash limited to one side of the body, adhering to a single dermatome and not crossing the midline. This rash comprises clusters of vesicles on an erythematous base, which typically crust over within ten days and may take up to four weeks to heal completely. The rash is often accompanied by varying degrees of pain, ranging from mild discomfort to severe, debilitating pain. Before the rash appears, patients may experience a prodromal phase characterized by pain, itching, or paresthesia in the affected dermatome, signaling the condition's onset [4].

Patients with HZ may also suffer from hypersensitivity, tingling sensations, aching, or burning pain, which can significantly impact their quality of life [2, 5]. Certain risk factors are known to predispose individuals to the development of HZ. These include chronic conditions like malignancies, diabetes mellitus, and tuberculosis, as well as the use of immunosuppressive medications, HIV infection, and exposure to radiotherapy [6]. Additionally, studies show that approximately 95% of immunocompetent individuals over 50 are seropositive for VZV, significantly increasing their likelihood of developing HZ as their immune system weakens with age [7].

HZ progresses through three distinct clinical stages. The first stage (pre-eruptive or pre-herpetic neuralgia) lasts 1 to 10 days. It is characterized by sensory disturbances, including pain, tingling, or itching, confined to one or more dermatomes. Systemic symptoms such as malaise, muscle aches, headaches, and photophobia may also accompany these sensory phenomena. This stage often causes diagnostic uncertainty, as its symptoms can mimic other conditions, delaying treatment [4].

The Acute Eruptive Stage, the second stage, involves the development of the characteristic vesicular rash. The lesions are often painful and may coalesce into larger patches. The rash resolves within 10 to 15 days, but in some cases, residual scarring may persist. This stage can be particularly distressing for patients due to the combination of pain and visible skin involvement. Prompt antiviral therapy during this phase has been shown to reduce the duration and severity of symptoms and the risk of complications like post-herpetic neuralgia [8].

The thirst stage, Chronic Stage or Post-herpetic Neuralgia, is a potential progression of HZ, characterized by pain persisting for months after the resolution of the rash. This complication is more common in older adults and those who experienced severe acute symptoms [4, 8]. Given the broad spectrum of symptoms and potential for significant complications, early diagnosis and intervention are crucial. Promptly initiated antiviral medications can shorten the disease course and reduce the likelihood of complications. Immunization against VZV in older adults has also emerged as a critical preventive strategy, highlighting the importance of public health measures in reducing the burden of HZ [8].

In the chronic stage (post-herpetic neuralgia), considered the third phase, some patients experience persistent pain lasting more than 30 days after the resolution of the acute infection. This condition can significantly affect the quality of life and is more common in older individuals and those with severe initial symptoms [4]. Several predisposing factors have been associated with the occurrence of HZ, including malignancies, diabetes, tuberculosis, immunosuppressive drugs, HIV infection, and radiation therapy [9]. Additionally, about 95% of immunocompetent individuals over 50 are seropositive for VZV, which increases their risk of developing HZ [10].

Over the years, global demographic changes have shifted toward an increase in the elderly population. With advancing age, the incidence of HZ also rises, suggesting a greater anticipated impact [11]. The high risk of HZ in older patients is likely due to immunosenescence, a condition in which the immune system gradually deteriorates with age. The VZV is typically maintained in a latent state within the sensory dorsal root ganglia by specific cell-mediated immunity [12]. While cellular immunity naturally declines over time, it is usually bolstered by exogenous and endogenous mechanisms, preventing VZV reactivation and the development of HZ.

Exogenous boosting occurs through repeated exposure to live VZV, resulting in subclinical infections rapidly controlled by cell-mediated immune processes [12]. Endogenously, subclinical reactivation of VZV stimulates CD4+ cells to release cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) [13].

In elderly patients with reduced immune function, cell-mediated immunity specific to VZV (including CD4, CD8, and memory T cells) falls below the threshold required to maintain viral latency. This increases the risk of VZV reactivation and the development of herpes zoster in this population [11]. HZ can lead to various complications, some of which are serious or even life-threatening. The most common complication of HZ is post-herpetic neuralgia, often defined as chronic pain that persists or emerges three months after the initial rash or HZ diagnosis. This condition is associated with an average maximum pain score of ≥3 on the Likert scale, as measured by the Zoster Brief Pain Inventory [14].

Studies have shown that HZ and PHN negatively affect healthy aging and quality of life [15]. Other common complications of HZ include ocular, neurological, and dermatological issues [12]. Some of these complications have severe health impacts, such as Ramsay Hunt syndrome, which can lead to facial paralysis or delayed contralateral hemiparesis [16]. Additionally, chronic infections have significant clinical relevance [17]. The primary goals of herpes zoster treatment are to reduce pain, accelerate healing, and prevent complications. Antiviral therapy, initiated promptly after diagnosis, reduces the risk of post-herpetic neuralgia. Corticosteroids may help manage pain and skin lesions.

Other aspects of treatment include isolating the patient and managing skin lesions locally. Patient isolation is crucial to prevent nosocomial infections [18].

Over the years, a worldwide shift has been toward an aging population. A higher impact of HZ can be anticipated, given that the incidence of HZ rises with age [19]. If HZ is not treated or prevented, it may increase the co-morbidities of elderly individuals, which would be detrimental to their quality of life [20, 21]. Immunizations have contributed to lower morbidity and mortality rates from various diseases in a range of age groups [22]. As declined by the World Health Organization (WHO) In 2016 (last available estimates), approximately 67% of the global population had HSV-1 infection (oral or genital), the infection acquired mostly throughout childhood [23].

This study was carried out to determine the level of knowledge about herpes zoster virus among students of the College of Health and Medical Technologies in Baghdad.

Instrument and Methods

This is an analytic cross-sectional study of senior students of the College of Health and Medical Technologies in Baghdad, examining their knowledge of the herpes zoster virus from November 2023 to February 2024. All fourth-year students (n=215) were collected as samples.

Data was collected using a questionnaire designed by the supervisor and the researcher based on scientific books, research, and studies. Then, the questionnaire was sent to experts to determine its validity. The questionnaire was divided into two parts; demographic characteristics and general information about the herpes zoster virus. This part had 9 questions; Each had multiple choices, and each should be answered (yes, no, don't know). The correct answer was given 3 scores, the false answer was given 1 score, and “don't know” was given 2 scores. The maximum knowledge score was 27, and the minimum score was 9, so the poor score was <18, the acceptable score was 18-22.5, and the good score was ≥22.5.

Data analysis was carried out using the available statistical package of SPSS 24 software. Data were presented in simple measures of frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and range (minimum-maximum values). The significance of the difference of different percentages (qualitative data) was tested using the Chi-square test.

Findings

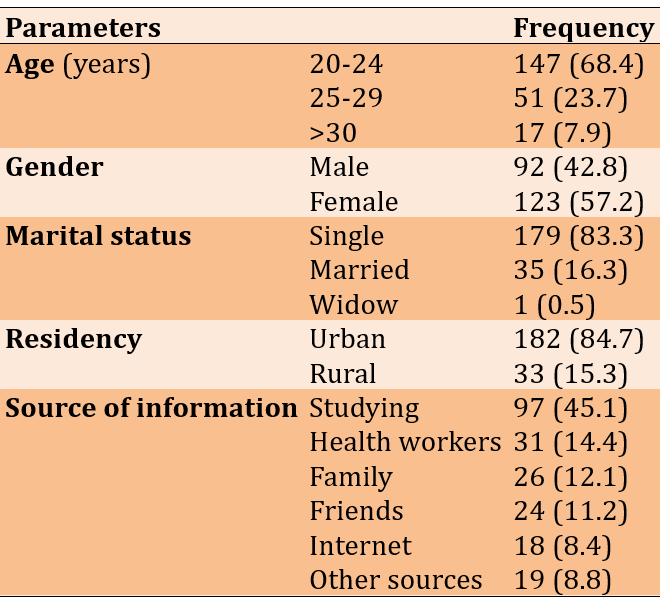

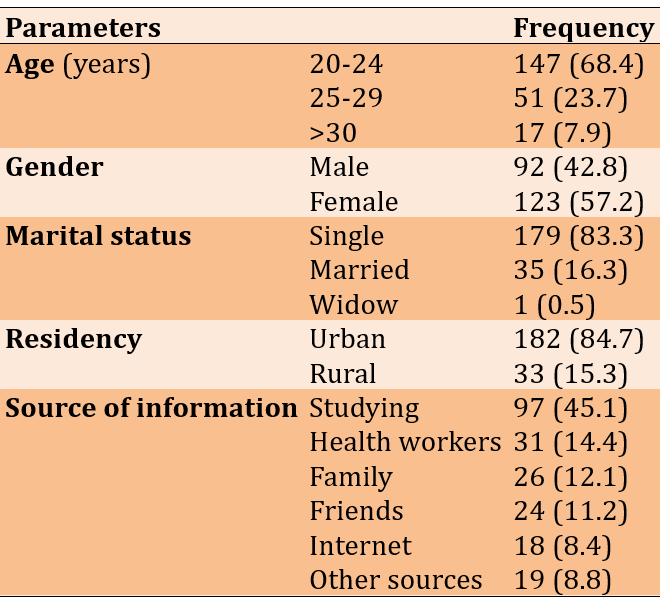

Most of the studied sample (68.4%) were in the 20-24 age group (24.6±3.4); 57.2% were female, 83.3% were single, and 84.7% lived in urban areas. Information was mostly received from studying (45.1%; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency (the numbers in parentheses are percentages) of the demographic parameters of participants

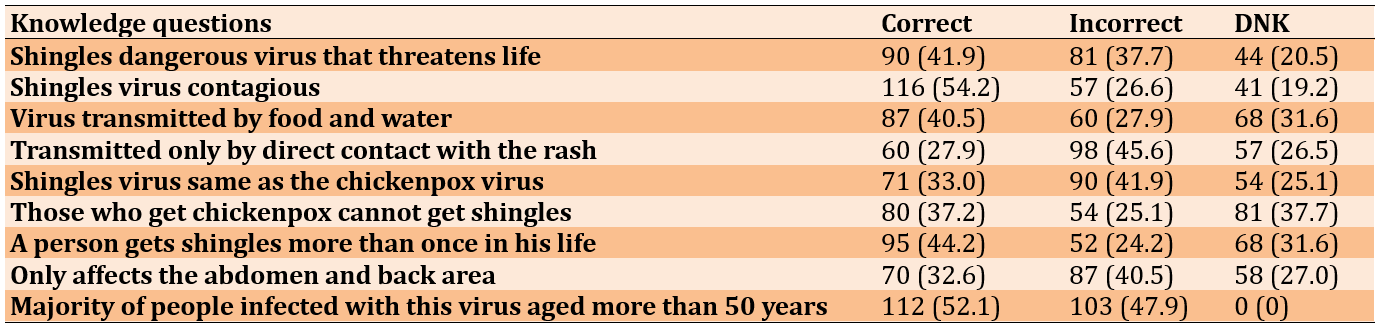

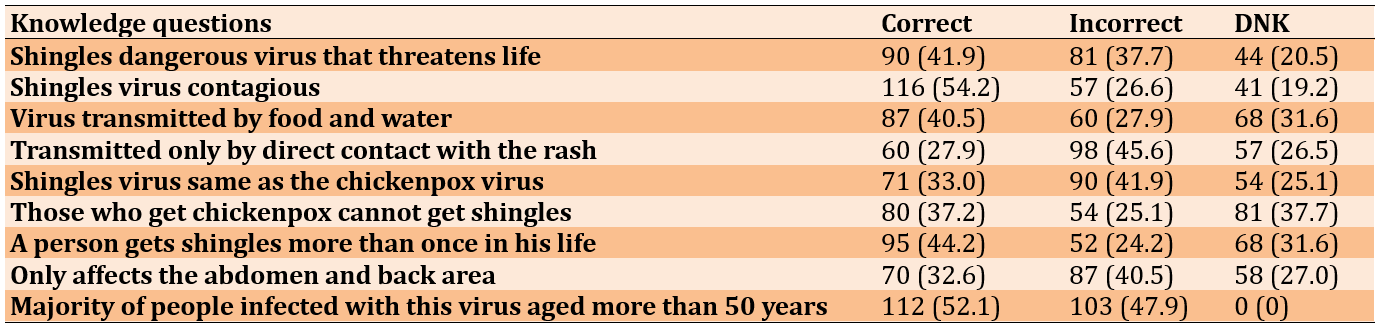

Several questions were asked to determine students' level of knowledge regarding herpes zoster, a dangerous virus that threatens life. Approximately 42% had the correct answers. The major participants answered correctly when they asked the following questions (Shingles virus contagious, virus transmitted by food and water, a person gets shingles more than once in his life, and most people infected with this virus aged more than 50 years). Questions such as disease transmission, Shingles virus, the same as the chickenpox virus, and body parts affected were answered incorrectly. 37% of study samples didn’t know if the person who gets chickenpox cannot get shingles (Table 2).

Table 2. Knowledge questions for the studied samples

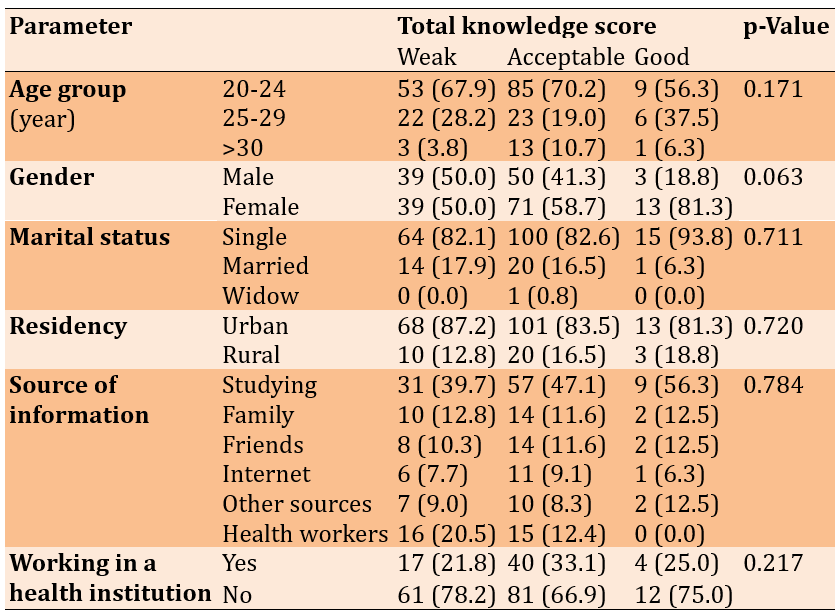

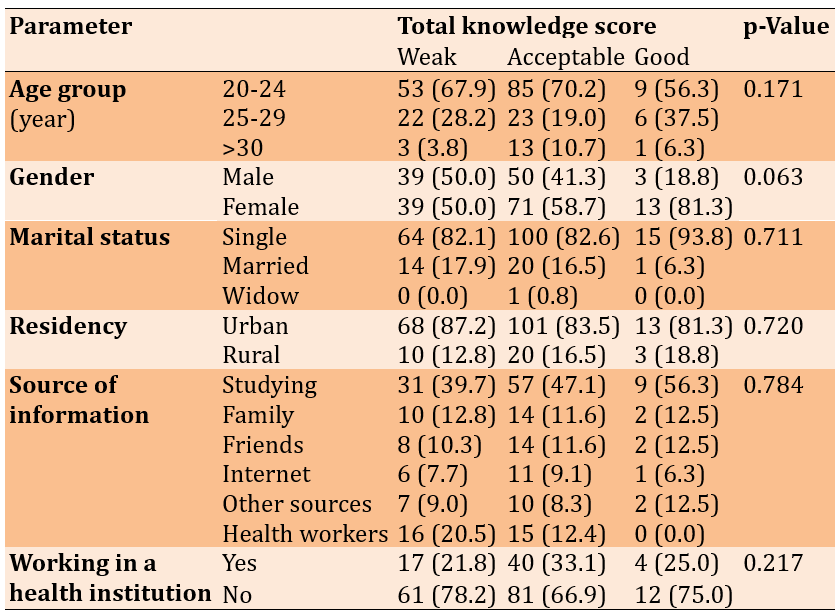

No significant association was found between knowledge score and demographic parameters (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. Association between demographic parameters and total knowledge score

Most study samples had acceptable knowledge scores (56%), 36% had weak scores, and just 8% had good scores.

Discussion

Herpes zoster is a disease primarily associated with aging and can profoundly impact the quality of life of those affected. The underlying cause of HZ is the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which remains dormant in the body after an individual has been infected with chickenpox in childhood. As people age, their immune systems, particularly cell-mediated immunity, naturally decline, creating a favorable environment for the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus [24]. This decline in immunity is a significant factor in the higher incidence of HZ among older adults. While the disease can occur at any age, the likelihood increases with age, especially in individuals over 50, due to the waning of immune defenses, which leaves them more vulnerable to infections such as HZ. This phenomenon is particularly alarming given that older adults often experience more severe outcomes from the disease, including persistent pain, complications, and a diminished quality of life.

In the current study, most participants demonstrated adequate knowledge about herpes zoster, with the largest group (56%) reporting fair or acceptable awareness of the disease and 8% indicating a good understanding. This suggests a relatively positive trend in awareness among the study population, which could be attributed to ongoing health education campaigns or accessible healthcare resources. These findings are consistent with research conducted by Hesham et al. in Malaysia, where a significant proportion of participants had sufficient knowledge about herpes zoster, highlighting the importance of informed populations in preventing and managing such diseases [25]. However, it is crucial to note that while the overall awareness in our study sample was reasonable, it may not be representative of broader populations, as factors such as education level, healthcare access, and public health campaigns can vary significantly from region to region.

Contrastingly, a study by Shanbari et al. [26] in Saudi Arabia reported alarming gaps in knowledge, with only 7.8% of individuals at risk having high knowledge about herpes zoster and a mere 3.1% aware of the availability of the herpes zoster vaccine. These figures indicate that while some regions, such as Malaysia and our study population, may exhibit relatively higher levels of awareness, other regions still face significant educational deficits regarding the disease. This disparity underscores the need for targeted health education interventions that address these gaps and promote awareness about the risks associated with herpes zoster and the preventative measures available, such as vaccination. The differing levels of knowledge across regions highlight the importance of culturally sensitive approaches to health education that consider local healthcare infrastructures, societal attitudes, and historical experiences with infectious diseases.

Moreover, the findings from a study conducted in South Korea reinforce the idea that certain populations can possess high awareness about both herpes zoster and the corresponding vaccine. In this study, over 80% of participants understood the disease, and over half were aware of the vaccine’s existence [27]. This result suggests that proactive public health measures, such as national immunization programs and widespread awareness campaigns, can significantly improve knowledge and increase vaccination rates, particularly among vulnerable populations. When individuals are well-informed about the risks of herpes zoster and the availability of preventive measures, they are more likely to take steps to protect themselves, such as seeking vaccination.

In contrast, the findings from a study in Hong Kong highlight the complex nature of public awareness regarding herpes zoster [28]. Despite acknowledging the potential health impacts of the disease, many older adults expressed a lack of concern about contracting herpes zoster. This disconnect between awareness and concern presents a unique challenge for public health officials. It suggests that while individuals may be aware of the disease, they may not fully appreciate the severity of its consequences or may underestimate their own risk of developing the disease. Such a mindset can significantly hinder vaccination efforts, as individuals may not perceive a strong enough incentive to take preventive action. This highlights the need to improve awareness about the disease and address misconceptions and concerns that might prevent people from engaging in preventive behaviors, such as vaccination.

In this study, regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants, the highest percentage (68.4%) was in the age group 20-25 years. The lowest percentage (7.9%) of the studied sample was in the group >30 years; the percentage of females in the studied sample (57.2%) was more than the percentage of male participants (42.8%). These results are similar when compared with the result of a similar study conducted in Namibia by Tomas & Kampanza, who found that a higher percentage of participants was in the age group 18-25, and regarding gender, found the proportion of females was slightly higher than the males as well, the percentage of female was 56%. In comparison, the percentage of males was 44% [29]. Regarding the general knowledge about herpes zoster, the correct answer about shingles as a dangerous virus that threatens life was 41.9%. This result agreed with what had been reported in a study conducted by Hesham et al. at the University of Kebangsaan Malaysia, who found that 40.8% answered correctly that varicella can be fatal [25]. In this study, only 27.9% had correct knowledge about the transmission of the virus. This result was lower than what had been reported in the United Arab Emirates by Arif & Qadir, who found that most of the study samples knew about the transmission of the virus; this difference may be due to the difference in societies [30]. In the current study, about 52.1% had correct answers about the majority of people who are older than 50 years infected with this virus. This result disagrees with the percentage of correct answers (71%) found in a study conducted in Namibia by Tomas & Kampanza. This differs due to the low knowledge of participants in our study about the risk group who may infected with this virus. Older adults have a greater risk of developing complications from shingles, typically due to having weaker immune systems [29].

The variations in knowledge levels across studies underscore the importance of tailored public health education initiatives. While some studies indicate a fair level of awareness among certain populations, significant gaps remain that could impact vaccination rates and overall public health outcomes. For instance, while students in Malaysia showed reasonable knowledge levels, those in Saudi Arabia exhibited much lower awareness regarding both HZ and its vaccination.

The findings suggest that educational campaigns should increase awareness about herpes zoster transmission, its complications, and preventive measures such as vaccination. Engaging college students through workshops or seminars could enhance their understanding and encourage them to disseminate accurate information within their communities. Awareness sessions and scientific symposiums from time to time on communicable diseases should performed in society and encourage students to participate in them. More detailed and accurate studies are needed to diagnose these gaps and work to address them in the future.

Conclusion

The overall knowledge score regarding herpes zoster virus among students of the College of Health and Medical Technologies for all departments was acceptable. There was no significant association between knowledge score and demographic variables.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all students participating in the sample.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Middle Technical University, Baghdad, Iraq.

Conflicts of Interests: There were no conflicts.

Authors' Contribution: Noori TA (First Author), Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (49%); Chiad IA (Second Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Taqi FMM (Third Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (44%); Sabah HG (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (2%)

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Herpes zoster (HZ), commonly called shingles, is a highly contagious condition caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). This virus remains latent within the cranial sensory and spinal ganglia after an individual has had an initial varicella (chickenpox) infection, typically occurring during childhood or adolescence [1, 2]. As a result, HZ only occurs in individuals previously infected with chickenpox [3].

The clinical presentation of HZ primarily involves a dermatological rash limited to one side of the body, adhering to a single dermatome and not crossing the midline. This rash comprises clusters of vesicles on an erythematous base, which typically crust over within ten days and may take up to four weeks to heal completely. The rash is often accompanied by varying degrees of pain, ranging from mild discomfort to severe, debilitating pain. Before the rash appears, patients may experience a prodromal phase characterized by pain, itching, or paresthesia in the affected dermatome, signaling the condition's onset [4].

Patients with HZ may also suffer from hypersensitivity, tingling sensations, aching, or burning pain, which can significantly impact their quality of life [2, 5]. Certain risk factors are known to predispose individuals to the development of HZ. These include chronic conditions like malignancies, diabetes mellitus, and tuberculosis, as well as the use of immunosuppressive medications, HIV infection, and exposure to radiotherapy [6]. Additionally, studies show that approximately 95% of immunocompetent individuals over 50 are seropositive for VZV, significantly increasing their likelihood of developing HZ as their immune system weakens with age [7].

HZ progresses through three distinct clinical stages. The first stage (pre-eruptive or pre-herpetic neuralgia) lasts 1 to 10 days. It is characterized by sensory disturbances, including pain, tingling, or itching, confined to one or more dermatomes. Systemic symptoms such as malaise, muscle aches, headaches, and photophobia may also accompany these sensory phenomena. This stage often causes diagnostic uncertainty, as its symptoms can mimic other conditions, delaying treatment [4].

The Acute Eruptive Stage, the second stage, involves the development of the characteristic vesicular rash. The lesions are often painful and may coalesce into larger patches. The rash resolves within 10 to 15 days, but in some cases, residual scarring may persist. This stage can be particularly distressing for patients due to the combination of pain and visible skin involvement. Prompt antiviral therapy during this phase has been shown to reduce the duration and severity of symptoms and the risk of complications like post-herpetic neuralgia [8].

The thirst stage, Chronic Stage or Post-herpetic Neuralgia, is a potential progression of HZ, characterized by pain persisting for months after the resolution of the rash. This complication is more common in older adults and those who experienced severe acute symptoms [4, 8]. Given the broad spectrum of symptoms and potential for significant complications, early diagnosis and intervention are crucial. Promptly initiated antiviral medications can shorten the disease course and reduce the likelihood of complications. Immunization against VZV in older adults has also emerged as a critical preventive strategy, highlighting the importance of public health measures in reducing the burden of HZ [8].

In the chronic stage (post-herpetic neuralgia), considered the third phase, some patients experience persistent pain lasting more than 30 days after the resolution of the acute infection. This condition can significantly affect the quality of life and is more common in older individuals and those with severe initial symptoms [4]. Several predisposing factors have been associated with the occurrence of HZ, including malignancies, diabetes, tuberculosis, immunosuppressive drugs, HIV infection, and radiation therapy [9]. Additionally, about 95% of immunocompetent individuals over 50 are seropositive for VZV, which increases their risk of developing HZ [10].

Over the years, global demographic changes have shifted toward an increase in the elderly population. With advancing age, the incidence of HZ also rises, suggesting a greater anticipated impact [11]. The high risk of HZ in older patients is likely due to immunosenescence, a condition in which the immune system gradually deteriorates with age. The VZV is typically maintained in a latent state within the sensory dorsal root ganglia by specific cell-mediated immunity [12]. While cellular immunity naturally declines over time, it is usually bolstered by exogenous and endogenous mechanisms, preventing VZV reactivation and the development of HZ.

Exogenous boosting occurs through repeated exposure to live VZV, resulting in subclinical infections rapidly controlled by cell-mediated immune processes [12]. Endogenously, subclinical reactivation of VZV stimulates CD4+ cells to release cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) [13].

In elderly patients with reduced immune function, cell-mediated immunity specific to VZV (including CD4, CD8, and memory T cells) falls below the threshold required to maintain viral latency. This increases the risk of VZV reactivation and the development of herpes zoster in this population [11]. HZ can lead to various complications, some of which are serious or even life-threatening. The most common complication of HZ is post-herpetic neuralgia, often defined as chronic pain that persists or emerges three months after the initial rash or HZ diagnosis. This condition is associated with an average maximum pain score of ≥3 on the Likert scale, as measured by the Zoster Brief Pain Inventory [14].

Studies have shown that HZ and PHN negatively affect healthy aging and quality of life [15]. Other common complications of HZ include ocular, neurological, and dermatological issues [12]. Some of these complications have severe health impacts, such as Ramsay Hunt syndrome, which can lead to facial paralysis or delayed contralateral hemiparesis [16]. Additionally, chronic infections have significant clinical relevance [17]. The primary goals of herpes zoster treatment are to reduce pain, accelerate healing, and prevent complications. Antiviral therapy, initiated promptly after diagnosis, reduces the risk of post-herpetic neuralgia. Corticosteroids may help manage pain and skin lesions.

Other aspects of treatment include isolating the patient and managing skin lesions locally. Patient isolation is crucial to prevent nosocomial infections [18].

Over the years, a worldwide shift has been toward an aging population. A higher impact of HZ can be anticipated, given that the incidence of HZ rises with age [19]. If HZ is not treated or prevented, it may increase the co-morbidities of elderly individuals, which would be detrimental to their quality of life [20, 21]. Immunizations have contributed to lower morbidity and mortality rates from various diseases in a range of age groups [22]. As declined by the World Health Organization (WHO) In 2016 (last available estimates), approximately 67% of the global population had HSV-1 infection (oral or genital), the infection acquired mostly throughout childhood [23].

This study was carried out to determine the level of knowledge about herpes zoster virus among students of the College of Health and Medical Technologies in Baghdad.

Instrument and Methods

This is an analytic cross-sectional study of senior students of the College of Health and Medical Technologies in Baghdad, examining their knowledge of the herpes zoster virus from November 2023 to February 2024. All fourth-year students (n=215) were collected as samples.

Data was collected using a questionnaire designed by the supervisor and the researcher based on scientific books, research, and studies. Then, the questionnaire was sent to experts to determine its validity. The questionnaire was divided into two parts; demographic characteristics and general information about the herpes zoster virus. This part had 9 questions; Each had multiple choices, and each should be answered (yes, no, don't know). The correct answer was given 3 scores, the false answer was given 1 score, and “don't know” was given 2 scores. The maximum knowledge score was 27, and the minimum score was 9, so the poor score was <18, the acceptable score was 18-22.5, and the good score was ≥22.5.

Data analysis was carried out using the available statistical package of SPSS 24 software. Data were presented in simple measures of frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and range (minimum-maximum values). The significance of the difference of different percentages (qualitative data) was tested using the Chi-square test.

Findings

Most of the studied sample (68.4%) were in the 20-24 age group (24.6±3.4); 57.2% were female, 83.3% were single, and 84.7% lived in urban areas. Information was mostly received from studying (45.1%; Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency (the numbers in parentheses are percentages) of the demographic parameters of participants

Several questions were asked to determine students' level of knowledge regarding herpes zoster, a dangerous virus that threatens life. Approximately 42% had the correct answers. The major participants answered correctly when they asked the following questions (Shingles virus contagious, virus transmitted by food and water, a person gets shingles more than once in his life, and most people infected with this virus aged more than 50 years). Questions such as disease transmission, Shingles virus, the same as the chickenpox virus, and body parts affected were answered incorrectly. 37% of study samples didn’t know if the person who gets chickenpox cannot get shingles (Table 2).

Table 2. Knowledge questions for the studied samples

No significant association was found between knowledge score and demographic parameters (p>0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. Association between demographic parameters and total knowledge score

Most study samples had acceptable knowledge scores (56%), 36% had weak scores, and just 8% had good scores.

Discussion

Herpes zoster is a disease primarily associated with aging and can profoundly impact the quality of life of those affected. The underlying cause of HZ is the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which remains dormant in the body after an individual has been infected with chickenpox in childhood. As people age, their immune systems, particularly cell-mediated immunity, naturally decline, creating a favorable environment for the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus [24]. This decline in immunity is a significant factor in the higher incidence of HZ among older adults. While the disease can occur at any age, the likelihood increases with age, especially in individuals over 50, due to the waning of immune defenses, which leaves them more vulnerable to infections such as HZ. This phenomenon is particularly alarming given that older adults often experience more severe outcomes from the disease, including persistent pain, complications, and a diminished quality of life.

In the current study, most participants demonstrated adequate knowledge about herpes zoster, with the largest group (56%) reporting fair or acceptable awareness of the disease and 8% indicating a good understanding. This suggests a relatively positive trend in awareness among the study population, which could be attributed to ongoing health education campaigns or accessible healthcare resources. These findings are consistent with research conducted by Hesham et al. in Malaysia, where a significant proportion of participants had sufficient knowledge about herpes zoster, highlighting the importance of informed populations in preventing and managing such diseases [25]. However, it is crucial to note that while the overall awareness in our study sample was reasonable, it may not be representative of broader populations, as factors such as education level, healthcare access, and public health campaigns can vary significantly from region to region.

Contrastingly, a study by Shanbari et al. [26] in Saudi Arabia reported alarming gaps in knowledge, with only 7.8% of individuals at risk having high knowledge about herpes zoster and a mere 3.1% aware of the availability of the herpes zoster vaccine. These figures indicate that while some regions, such as Malaysia and our study population, may exhibit relatively higher levels of awareness, other regions still face significant educational deficits regarding the disease. This disparity underscores the need for targeted health education interventions that address these gaps and promote awareness about the risks associated with herpes zoster and the preventative measures available, such as vaccination. The differing levels of knowledge across regions highlight the importance of culturally sensitive approaches to health education that consider local healthcare infrastructures, societal attitudes, and historical experiences with infectious diseases.

Moreover, the findings from a study conducted in South Korea reinforce the idea that certain populations can possess high awareness about both herpes zoster and the corresponding vaccine. In this study, over 80% of participants understood the disease, and over half were aware of the vaccine’s existence [27]. This result suggests that proactive public health measures, such as national immunization programs and widespread awareness campaigns, can significantly improve knowledge and increase vaccination rates, particularly among vulnerable populations. When individuals are well-informed about the risks of herpes zoster and the availability of preventive measures, they are more likely to take steps to protect themselves, such as seeking vaccination.

In contrast, the findings from a study in Hong Kong highlight the complex nature of public awareness regarding herpes zoster [28]. Despite acknowledging the potential health impacts of the disease, many older adults expressed a lack of concern about contracting herpes zoster. This disconnect between awareness and concern presents a unique challenge for public health officials. It suggests that while individuals may be aware of the disease, they may not fully appreciate the severity of its consequences or may underestimate their own risk of developing the disease. Such a mindset can significantly hinder vaccination efforts, as individuals may not perceive a strong enough incentive to take preventive action. This highlights the need to improve awareness about the disease and address misconceptions and concerns that might prevent people from engaging in preventive behaviors, such as vaccination.

In this study, regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants, the highest percentage (68.4%) was in the age group 20-25 years. The lowest percentage (7.9%) of the studied sample was in the group >30 years; the percentage of females in the studied sample (57.2%) was more than the percentage of male participants (42.8%). These results are similar when compared with the result of a similar study conducted in Namibia by Tomas & Kampanza, who found that a higher percentage of participants was in the age group 18-25, and regarding gender, found the proportion of females was slightly higher than the males as well, the percentage of female was 56%. In comparison, the percentage of males was 44% [29]. Regarding the general knowledge about herpes zoster, the correct answer about shingles as a dangerous virus that threatens life was 41.9%. This result agreed with what had been reported in a study conducted by Hesham et al. at the University of Kebangsaan Malaysia, who found that 40.8% answered correctly that varicella can be fatal [25]. In this study, only 27.9% had correct knowledge about the transmission of the virus. This result was lower than what had been reported in the United Arab Emirates by Arif & Qadir, who found that most of the study samples knew about the transmission of the virus; this difference may be due to the difference in societies [30]. In the current study, about 52.1% had correct answers about the majority of people who are older than 50 years infected with this virus. This result disagrees with the percentage of correct answers (71%) found in a study conducted in Namibia by Tomas & Kampanza. This differs due to the low knowledge of participants in our study about the risk group who may infected with this virus. Older adults have a greater risk of developing complications from shingles, typically due to having weaker immune systems [29].

The variations in knowledge levels across studies underscore the importance of tailored public health education initiatives. While some studies indicate a fair level of awareness among certain populations, significant gaps remain that could impact vaccination rates and overall public health outcomes. For instance, while students in Malaysia showed reasonable knowledge levels, those in Saudi Arabia exhibited much lower awareness regarding both HZ and its vaccination.

The findings suggest that educational campaigns should increase awareness about herpes zoster transmission, its complications, and preventive measures such as vaccination. Engaging college students through workshops or seminars could enhance their understanding and encourage them to disseminate accurate information within their communities. Awareness sessions and scientific symposiums from time to time on communicable diseases should performed in society and encourage students to participate in them. More detailed and accurate studies are needed to diagnose these gaps and work to address them in the future.

Conclusion

The overall knowledge score regarding herpes zoster virus among students of the College of Health and Medical Technologies for all departments was acceptable. There was no significant association between knowledge score and demographic variables.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all students participating in the sample.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Middle Technical University, Baghdad, Iraq.

Conflicts of Interests: There were no conflicts.

Authors' Contribution: Noori TA (First Author), Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst (49%); Chiad IA (Second Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Taqi FMM (Third Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (44%); Sabah HG (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher (2%)

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

References

1. Blair RJ. Varicella zoster virus. Pediatr Rev. 2019;40(7):375-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1542/pir.2017-0242]

2. Cohen JI. Clinical practice: Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):255-63. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp1302674]

3. Freer G, Pistello M. Varicella-zoster virus infection: Natural history, clinical manifestations, immunity and current and future vaccination strategies. New Microbiol. 2018;41(2):95-105. [Link]

4. Johnson RW, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Bijl M, Franco E, Gaillat J, Clara JG, et al. Herpes zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: A multidisciplinary perspective. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2015;3(4):109-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2051013615599151]

5. Schmader K. Herpes zoster. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(3):539-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cger.2016.02.011]

6. Babamahmoodi F, Alikhani A, Ahangarkani F, Delavarian L, Barani H, Babamahmoodi A. Clinical manifestations of herpes zoster, its comorbidities, and its complications in North of Iran from 2007 to 2013. Neurol Res Int. 2015;2015:896098. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2015/896098]

7. Shearer K, Maskew M, Ajayi T, Berhanu R, Majuba P, Sanne I, et al. Incidence and predictors of herpes zoster among antiretroviral therapy-naive patients initiating HIV treatment in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:56-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.10.016]

8. Johnson R, Rice A. Clinical practice: postherpetic neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1526-1533. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp1403062]

9. Kovac M, Lal H, Cunningham AL, Levin MJ, Johnson RW, Campora L. Complications of herpes zoster in immunocompetent older adults: incidence in vaccine and placebo groups in two large phase 3 trials. Vaccine. 2018;36(12):1537-1541. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.029]

10. Meyers JL, Madhwani S, Rausch D, Candrilli SD, Krishnarajah G, Yan S. Analysis of real-world health care costs among immunocompetent patients aged 50 years or older with herpes zoster in the United States. Hum Vaccine Immunother. 2017;13(8):1861-1872. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/21645515.2017.1324373]

11. Marra F, Parhar K, Huang B, Vadlamudi N. Risk factors for herpes zoster infection: a meta-analysis. Open Forum Infectious Dis. 2020;7(1):ofaa005. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ofid/ofaa005]

12. Oxman MN. Herpes zoster pathogenesis and cell-mediated immunity and immunosenescence. J Osteopat Med. 2009;109(62):13-17. [Link]

13. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, Cohrs RJ, Gershon MD, Gilden D, Yamanishi, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1(1):1-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2015.16]

14. Coplan PM, Schmader K, Nikas A, Chan IS, Choo P, Levin M. J, et al. Development of a measure of the burden of pain due to herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia for prevention trials: adaptation of the brief pain inventory. J Pain. 2004;5(6):344-356. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2004.06.001]

15. Lang P-O, Aspinall R. Vaccination for quality of life: herpes-zoster vaccines. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(4):1113-1122. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40520-019-01374-5]

16. Volpi A. Severe complications of herpes zoster. Herpes. 2007;14(2):35-39. [Link]

17. DeWane ME, Smith JS, DeSimone MS, Mostaghimi A. A case of refractory verrucous varicella zoster virus in a patient with persistent pancytopenia after CAR-T therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(3):e77. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bjd.21609]

18. Koshy E, Mengting L, Kumar H, Jianbo W. Epidemiology, treatment and prevention of herpes zoster: A comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:251. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_1021_16]

19. Wolfson LJ, Daniels VJ, Altland A, Black W, Huang W, Ou W. The impact of varicella vaccination on the incidence of varicella and Herpes Zoster in the United States: Updated evidence from observational databases, 1991-2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(6):995-1002. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/cid/ciz305]

20. Pickering G, Gavazzi G, Gaillat J, Paccalin M, Bloch K, Bouhassira D. Is herpes zoster an additional complication in old age alongside comorbidity and multiple medications? Results of the post hoc analysis of the 12-month longitudinal prospective observational ARIZONA cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009689. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009689]

21. Curran D, Oostvogels L, Heineman T, Matthews S, McElhaney J, McNeil S, et al. Quality of life impact of an adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine in adults aged 50 years and older. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1231-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/gerona/gly150]

22. Ciabattini A, Nardini C, Santoro F, Garagnani P, Franceschi C, Medaglini D. Vaccination in the elderly: The challenge of immune changes with aging. Semin Immunol. 2018;40:83-94. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.smim.2018.10.010]

23. WHO. Herpes simplex virus [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization [cited 2024, May, 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus. [Link]

24. Weinberg JM. Herpes zoster: Epidemiology, natural history, and common complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):S130-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.046]

25. Hesham R, Cheong JY, Hasni JM. Knowledge, attitude and vaccination status of varicella among students of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM). Med J Malaysia. 2009;64(3):257-62. [Link]

26. Al Shanbari N, Aldajani A, Almowallad F, Sodagar W, Almaghrabi H, Almuntashiri NS, et al. Assessment of the level of knowledge and attitude towards herpes zoster and its vaccination among individuals at risk in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2024:16(2). [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.53572]

27. Yang TU, Cheong HJ, Song JY, Noh JY, Kim WJ. Survey on public awareness, attitudes, and barriers for herpes zoster vaccination in South Korea. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:719-26. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/21645515.2015.1008885]

28. Lam AC, Chan MY, Chou HY, Ho SY, Li HL, Lo CY, et al. A cross-sectional study of the knowledge, attitude, and practice of patients aged 50 years or above towards herpes zoster in an out-patient setting. Hong Kong Med J. 2017;23(4):365. [Link]

29. Tomas N, Kampanza F. Awareness of varicella-zoster virus among undergraduate students at the University of Namibia. J Public Health Afr. 2022;13(2):1923. [Link] [DOI:10.4081/jphia.2022.1923]

30. Arif N, Qadir MI. Survey about the awareness of chicken pox among biology students. J Hum Virol Retrovirol. 2019;7(1):7-8. [Link] [DOI:10.15406/jhvrv.2019.07.00205]