Volume 16, Issue 3 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(3): 245-252 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.BMSU.REC.1402.069

History

Received: 2024/05/1 | Accepted: 2024/09/7 | Published: 2024/10/1

Received: 2024/05/1 | Accepted: 2024/09/7 | Published: 2024/10/1

How to cite this article

Basiri A, Abbasi Farajzadeh M, Mohammadian M, Heidaranlu E. Effect of Tabletop Exercise on the Preparedness Improvement of Military Hospitals in Mass Casualty Incidents. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (3) :245-252

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1457-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1457-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Health Research Center, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Health Research Center” and “Student Research Committee”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- “Nursing Care Research Center” and “Clinical Science Institute and Nursing Faculty”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- “Health Research Center” and “Student Research Committee”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- “Nursing Care Research Center” and “Clinical Science Institute and Nursing Faculty”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (554 Views)

Introduction

In recent decades, major accidents and disasters have been increasing globally, including in Iran. The occurrence of these incidents affects more people every day, disrupts the provision of health services, and slows down the development process [1, 2]. In accidents with mass casualties, not only are a large number of individuals in the affected community injured, but such incidents also lead to physical, mental, and social disabilities [3, 4]. Mass casualty incidents are those, in which hospital emergency service resources, including staff and equipment, cannot adequately respond due to the number and severity of injuries [5]. Given the high demand for health services during accidents and disasters, having a plan for preparedness and response is essential for effective hospital risk management [6, 7]. Developing a preparedness plan that includes training for all employees and regular exercises, along with forecasting the necessary resources, is crucial for incident management response [8]. Capacity building in hospitals, as the primary providers of health services during incidents with a high number of injuries, is a priority for the health system [9].

Health sector employees are the first group to respond to accidents and disasters involving mass casualties; therefore, their level of preparedness and appropriate response is a critical factor in determining the rates of death and potential injuries during such events [10, 11]. Exercises provide practical learning opportunities and serve as an effective method for assessing and improving personnel performance in simulated conditions based on various scenarios. Exercises empower personnel by enhancing their ability to analyze information and make decisions [12, 13]. These exercises are conducted for different purposes, including training personnel, increasing individual capabilities and skills, and identifying weaknesses and needs. Exercises can be categorized in various ways; one common method divides them into two types, including discussion-based and performance-based [14]. Performance-based training involves a form of training that combines practical work. This type of exercise is designed to evaluate plans, policies, memorandums, and procedures, clarify roles and responsibilities, and identify resource deficiencies in an operational environment. Performance-based training includes three types of exercises, including functional training and full-scale training [14, 15]. Unfortunately, recent studies have indicated that healthcare workers are not adequately prepared to respond to accidents. Various studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of discussion-based exercises, including roundtable exercises, in mass casualty incidents. Abbasi Dolatabadi et al. identified a lack of knowledge and preparation as factors contributing to emotional stress during the execution of duties in crisis and disaster situations. They believe that preparedness to respond to disasters enhances healthcare workers’ self-confidence and reduces the extent of damage and vulnerability when facing unforeseen events [16]. Khankeh et al. highlighted the trained workforce as one of the facilitating factors in providing health services [17, 18]. Kang et al. reported that training healthcare workers has long been recognized as a crucial component of disaster preparedness [19]. Experiences also indicate that health workers are not only inadequately prepared to respond to incidents, but inconsistencies and parallel or conflicting actions have exacerbated the situation, revealing a gap in crisis management methods. A scientific review of past experiences shows that the primary weakness of crisis management in hospitals is intra-organizational inconsistency and lack of coordination among primary responders, depending on the type and severity of incidents during disasters. One significant challenge is the unfamiliarity of healthcare workers with team functions in the context of crisis management. Unfortunately, most functions occur in isolated “islands,” leading to inefficiencies and an excess of responsible parties and incident commanders. Previous experiences have demonstrated that conducting training and various exercises focused on coordination and team performance, particularly among the members of the incident command system in hospitals, has resulted in better outcomes in crisis management [17, 19].

Achieving coordination and coherence among the various members of the incident command system involved in incidents requires a solid foundation, one of the key elements of which is team training, exercises, and coordination. Unfortunately, the prevailing approach to training for groups involved in accidents tends to focus on single-professional methods, which not only fail to prepare them for effective team performance but also foster an individualistic mindset. In a consolidated review study, Jose & Dufrene investigated the most effective methods or educational approaches to enhance the ability of healthcare workers to respond to a crisis. Their findings, based on a review of more than 190 primary studies, indicated that the most effective educational approach in this context is the implementation of roundtable exercises and simulations. To provide an effective, coordinated, and organized response to the impacts of various types of disasters and emergencies, the existence of emergency operation plans (EOPs) is essential [20]. However, it is important to note that this program should not only exist theoretically but should also be validated in written form through the execution of different types of exercises. Exercises are activities conducted with the purpose of training and enhancing capabilities.

Since the selected military hospital is located in a strategic area of Tehran, and preparedness to respond to accidents and disasters is particularly important in this region, the present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of training on accident and disaster management based on a practical approach. The study focused on the ability of members of the hospital incident command system (HICS) to manage mass casualties in a selected military hospital in Tehran.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sample

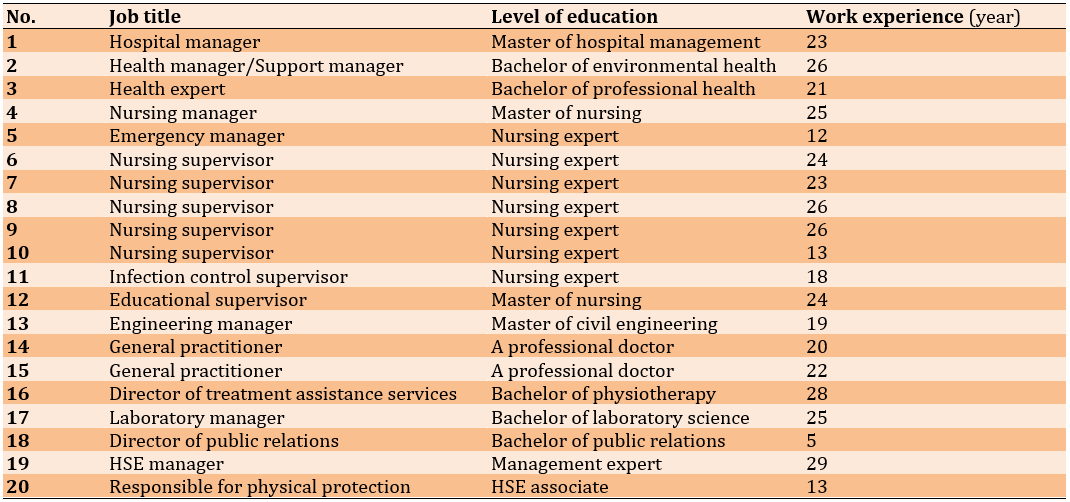

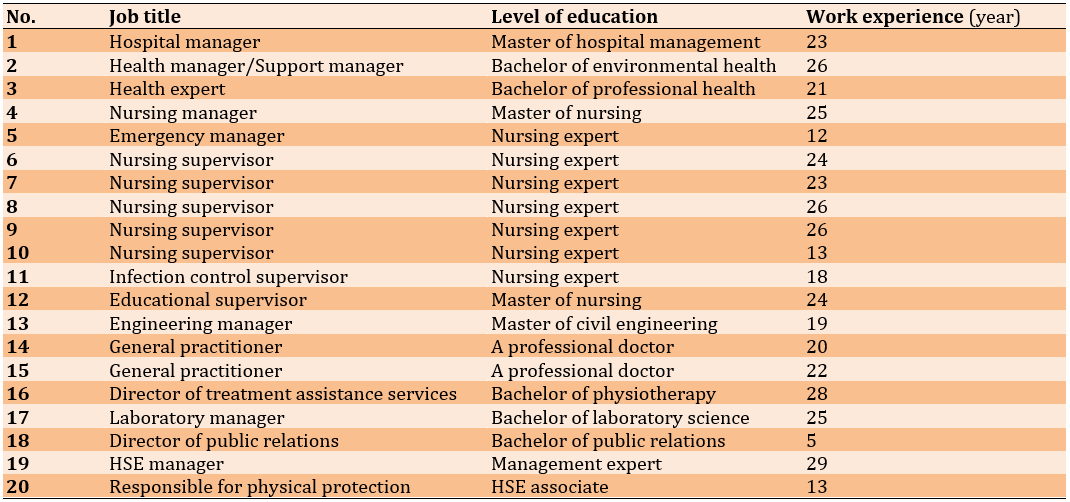

The current semi-experimental research involved a single group, including 20 directorate, senior and middle managers, doctors, nurses, and health and emergency managers, assessed before and after a tabletop exercise scenario focused on incidents with mass casualties in Tehran in 2023. The statistical population consisted of the members of the HICS who (Table 1).

Table 1. The statistical population of the research

Study instrument

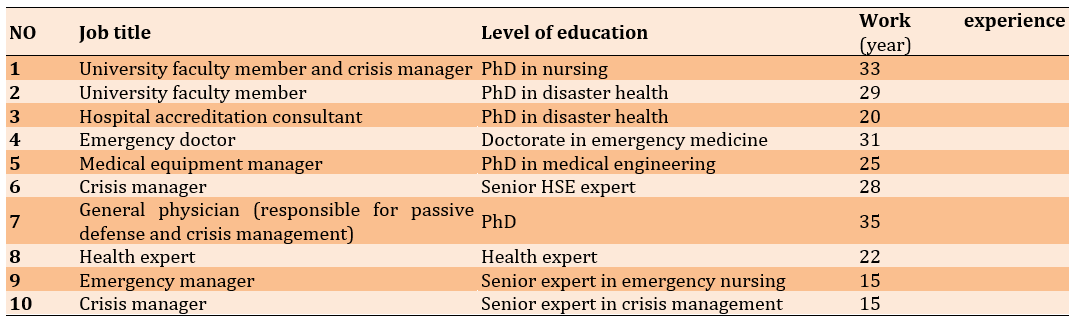

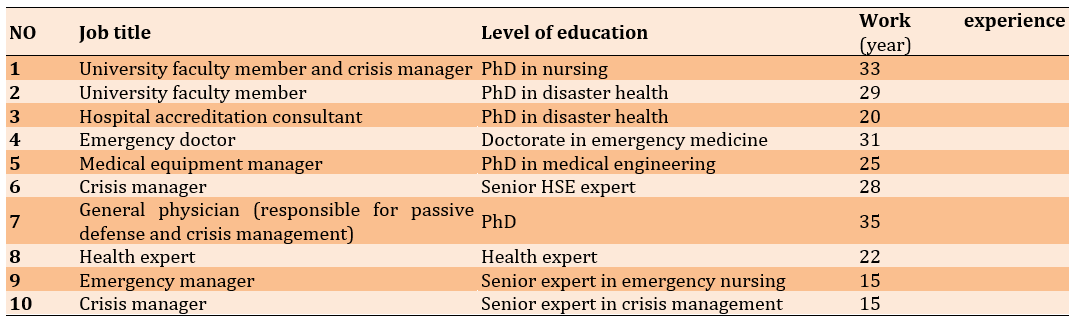

Data collection was conducted using a researcher-developed questionnaire, which underwent content and face validity assessments by ten experts. The questionnaire was designed to measure components of the hospital’s readiness regarding the HICS, overcapacity, and early warning system (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic information of experts and specialists in the content validity of the questionnaire

Data collection

After confirming the news of the accident and announcing the crisis code, the members of the HICS were summoned to the hospital’s command center by the commander. During the roundtable exercise, each process owner participating in the research was asked to describe their tasks. At the end of the roundtable exercise, the strengths and weaknesses, as well as the effectiveness of the training provided, were discussed through interaction, mutual thinking, and reflection.

The members of the HICS participated in a training workshop that included presentations on the theoretical foundations of crisis management and the HICS, along with descriptions of duties and the roles of the members defined in the HICS. To implement the roundtable exercise, the emergency operations center (EOC) of the University of Medical Sciences was informed of the incident by announcing the arrival of the injured at the news center, according to the prepared scenario. The intervention consisted of two two-day (4-hour) training workshops on accident and disaster risk management, which included presentations on the fundamentals of the HICS and a practical component involving the scenario-based roundtable exercise with the participation of the process owners.

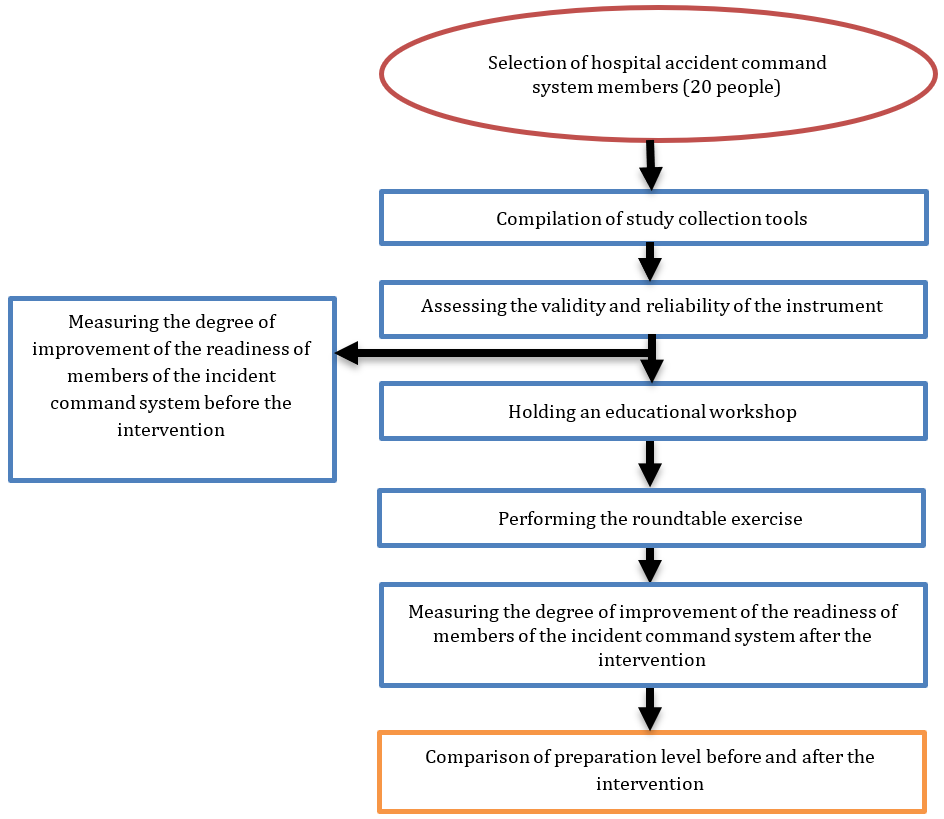

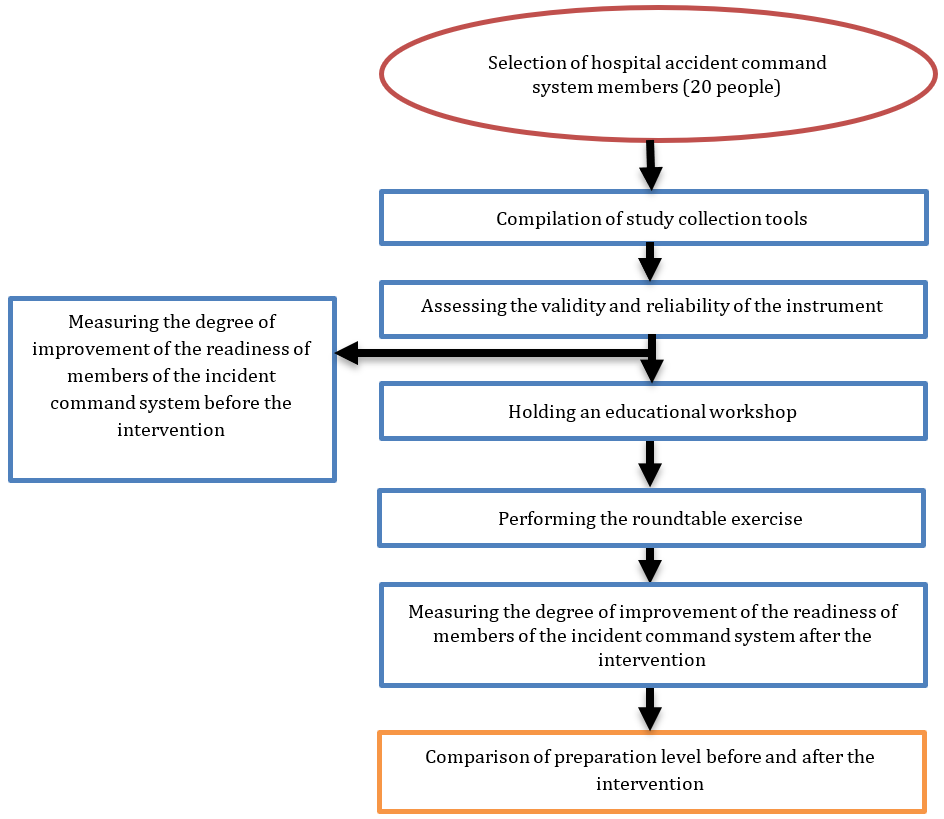

Statistical analysis

Data were collected before and after the intervention using a standard questionnaire to assess readiness, both prior to and following the roundtable exercise (Figure 1). SPSS version 21 software was used for data analysis and data were expressed using descriptive statistics.

Figure 1. Flowchart of research execution method

Findings

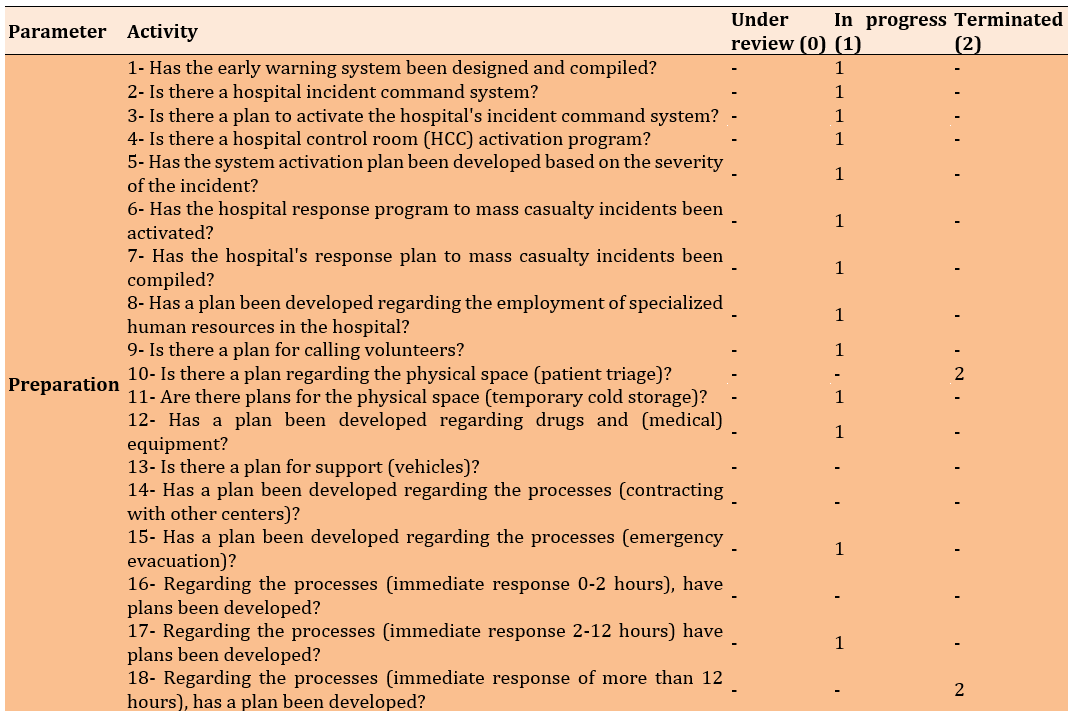

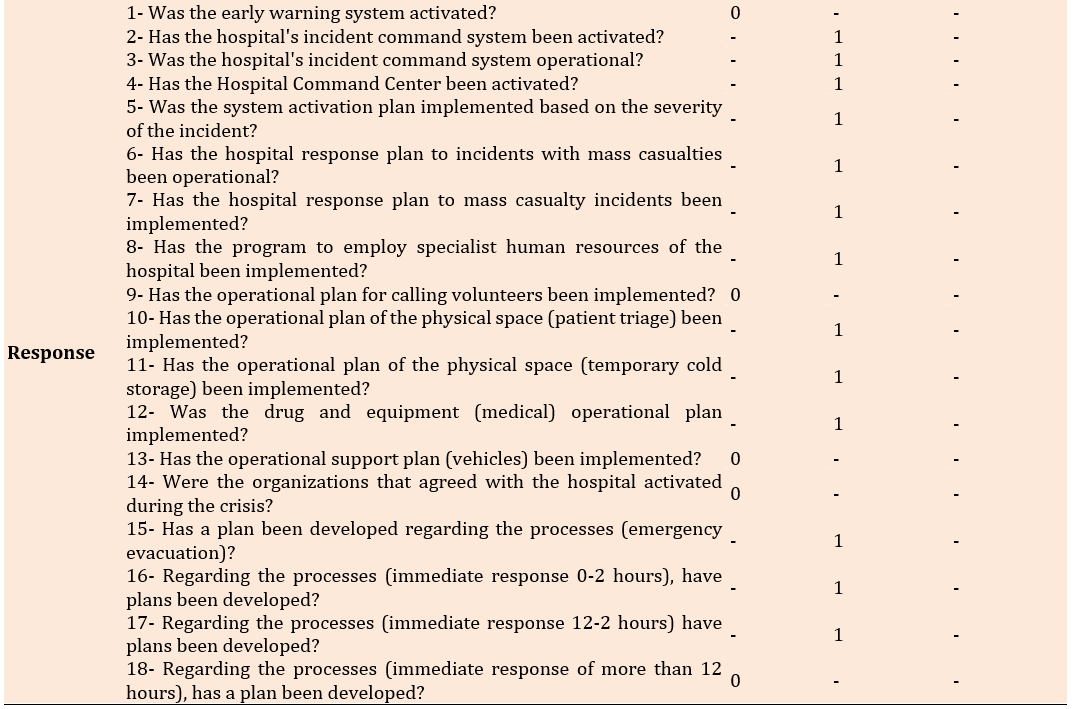

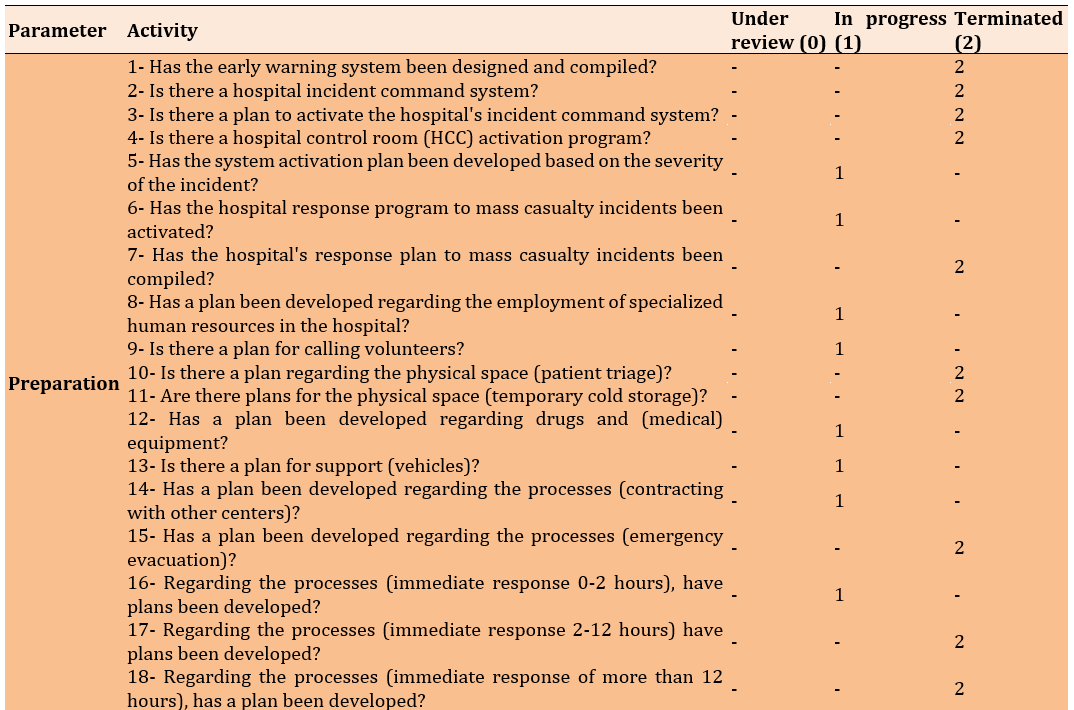

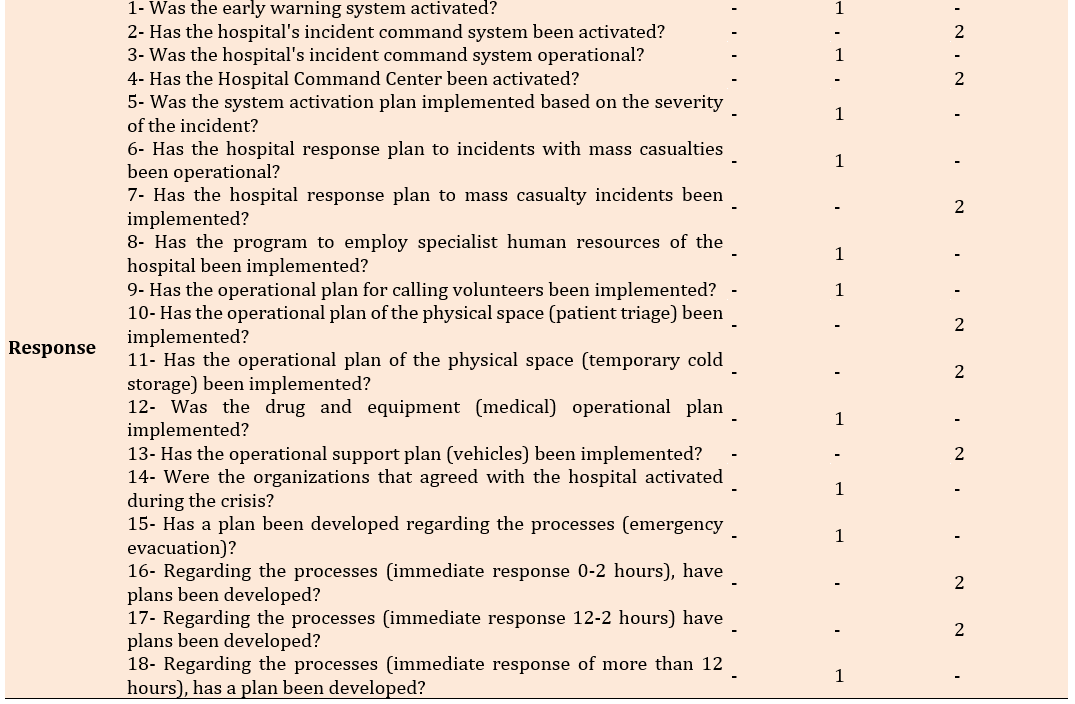

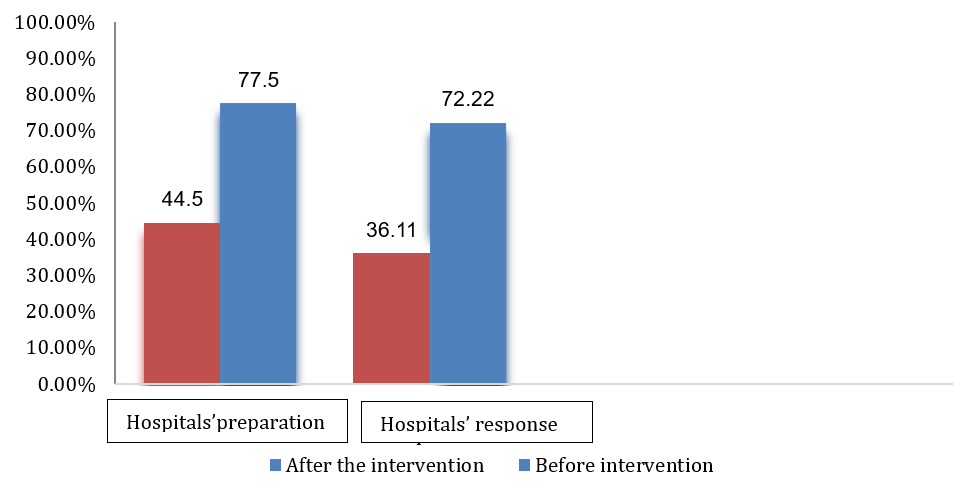

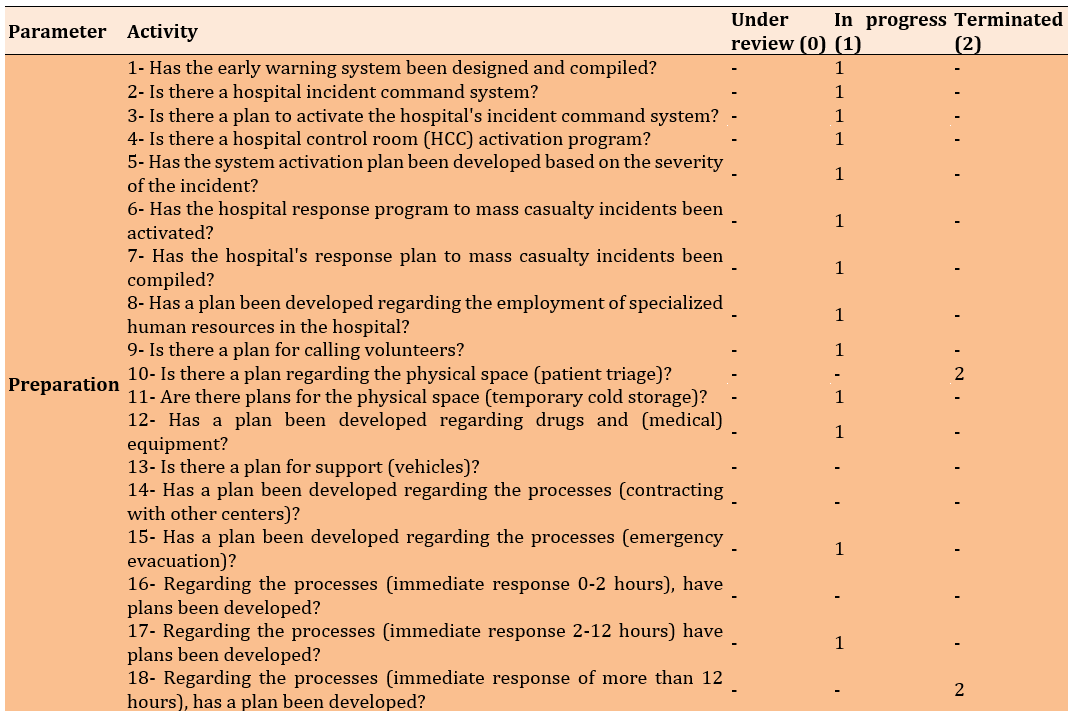

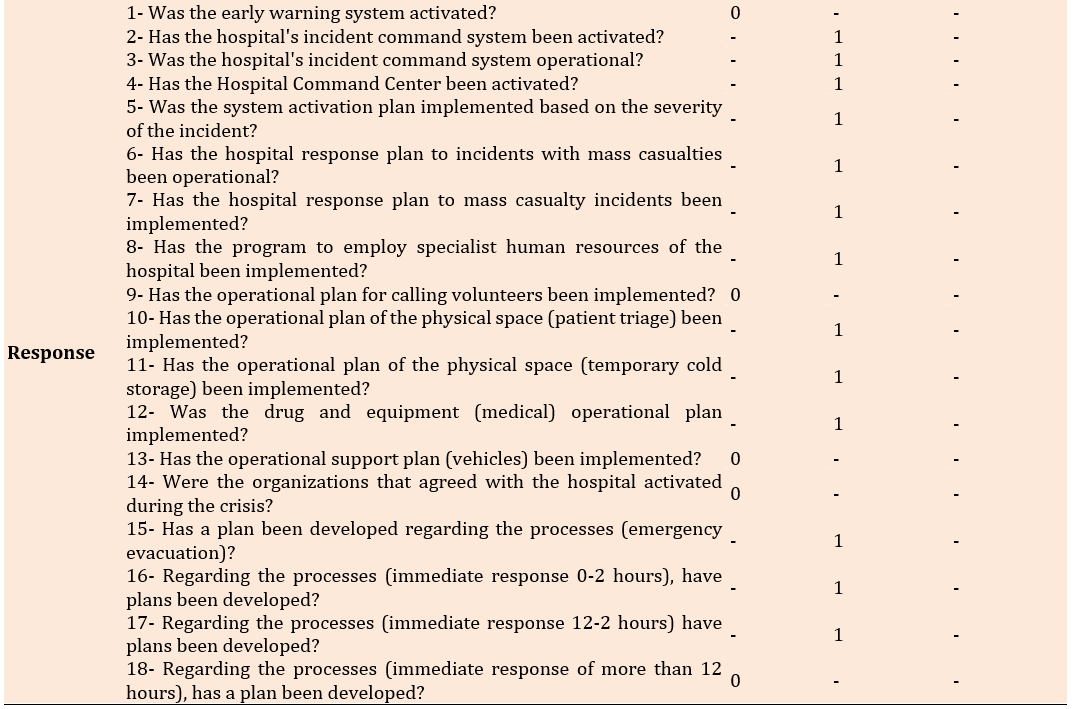

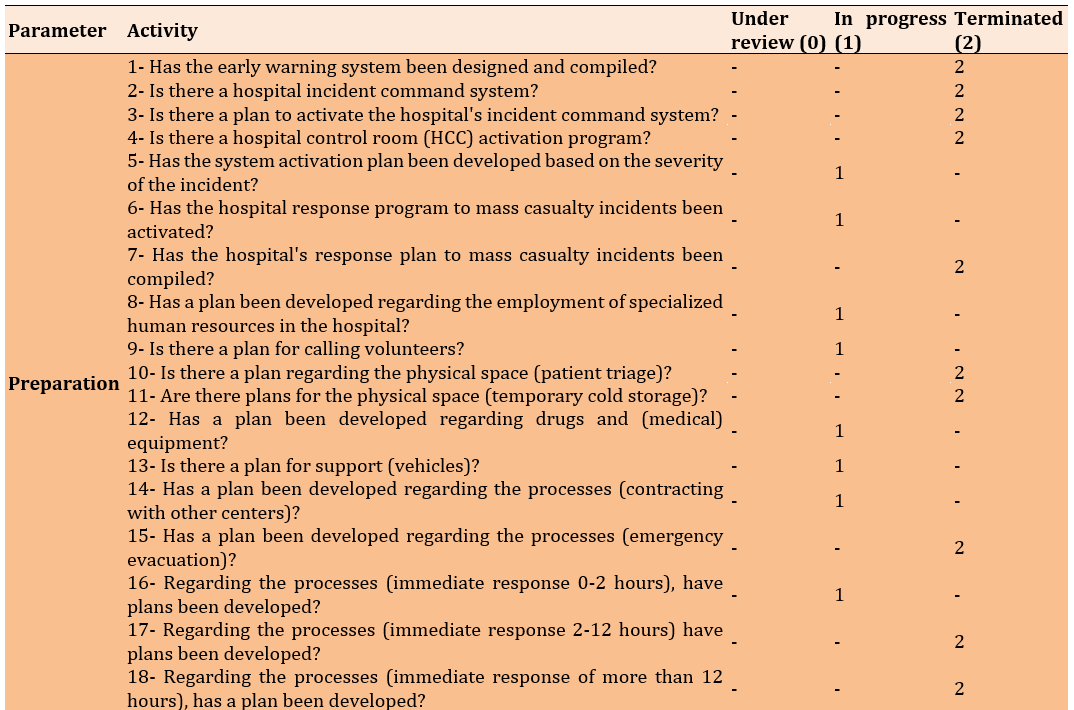

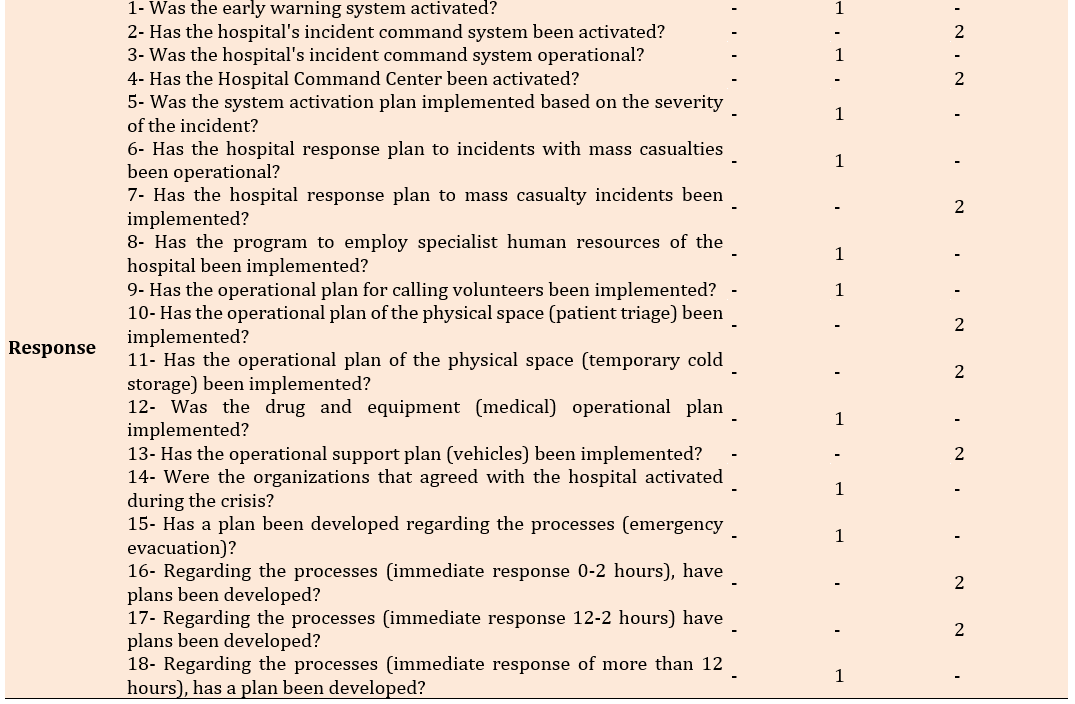

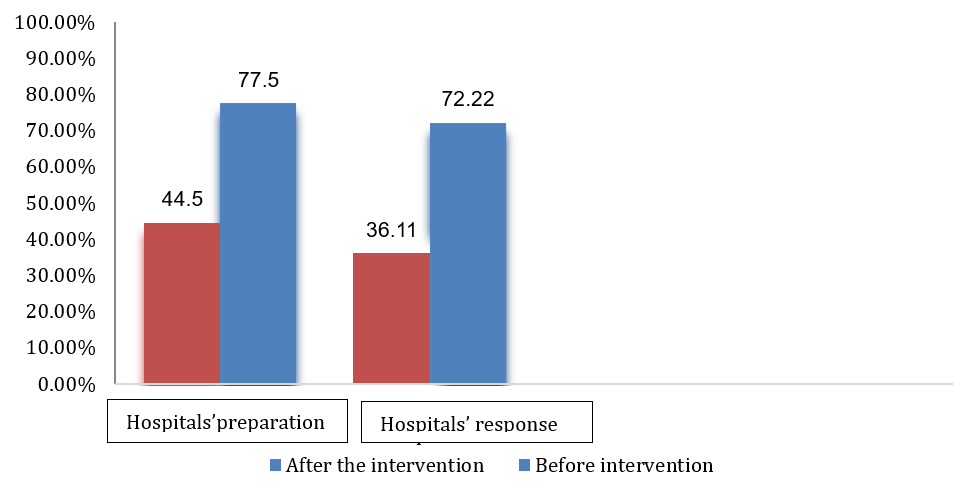

This study involved 20 members of the HICS and assessed the components of the early warning system, the incident command system, overcapacity, and operational plans were examined in two dimensions, including preparation and response, both before and after the roundtable exercise. Despite the impact of desk training on the readiness of members of the HICS to manage incidents with mass casualties, the average percentage of readiness and response before the intervention was 44.5% and 36.11%, respectively. After the intervention involving desk training, the percentage of readiness increased to 77.5%, while the hospital’s response score rose to 72.22%, which increased by 33% for readiness and 36.11% for response (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. Preparation scores before the roundtable exercise

Table 4. Preparation scores after the roundtable exercise

In total, the hospital improved by 33% in the readiness index and 36.11% in the response index, indicating that the roundtable exercise was effective in enhancing the hospital’s preparedness in the face of accidents and disasters (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of the hospital’s readiness and response percentages before and after the intervention.

Discussion

This study was designed to determine the effect of educational interventions and tabletop exercises on the preparedness of healthcare workers at a selected military hospital in Tehran to handle incidents involving mass casualties. Approximately half of the healthcare workers (48%) had faced crises and disasters, and 65.3% of nurses reported that they had received training in disaster response. However, most of them (92%) felt that they needed additional training, which may indicate that the training provided was either ineffective and insufficient or not delivered at the appropriate time.

In the study by Pek et al., evaluation outcomes across full-scale exercises are different, leading to challenges in consolidating the effectiveness of simulations into a single measure [21]. It is recommended that best evidence-based practices for simulation be adhered to in full-scale exercises so that training can translate into better outcomes for casualties during actual disasters or mass-casualty incidents. Additionally, the reporting of simulation use in full-scale exercises should be standardized using a framework, and the evaluation process should be rigorous to determine and compare effectiveness across full-scale exercises [21, 22].

In the study by Al-Romaihi et al., the evaluation outcomes indicated that the overall mean knowledge score regarding communicable disease (CD) threats among study participants is 75.0%, with the majority of participants having a favorable attitude toward CD preparedness during mass gatherings (MG) events. Participants achieved high scores in workshops on triaging, first aid, and infection control. Additionally, study participants had positive perceptions of the current preparedness of their respective hospitals to respond to CD outbreaks during MG events [23, 24].

Teng-Calleja et al. showed that the overall scores in the areas of knowledge, attitude, and performance increased significantly after the intervention compared to before [25, 26]. Xia et al. reported that students receiving the program display greater increases in knowledge and skills related to disaster preparedness than those in the control group. One month after the intervention, the experimental group still demonstrated significantly higher levels of disaster knowledge and skills than the control group. There were no statistically significant differences over time in attitude measures. This program enhanced students’ abilities, and the findings can serve as a basis for further developing public health education for all nurses. Chinese leaders of public health institutions and nursing administrators can create guidelines for public health nursing (PHN) competencies and prepare the public health nursing workforce to be effective in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery [27].

Nejadshafiee et al. indicated that the majority of experts (76%) assess the necessity of training and developing the required capabilities in nurses for handling accidents and disasters and caring for the injured as “very high,” while 23.53% rate it as “high” [28]. In the study by Mulyasari et al., the evaluation outcomes regarding the level of healthcare in dealing with disasters are reported to be average [29]. Fung et al. found that nurses in Hong Kong are not adequately prepared for disasters but are aware of the need for such preparation. Therefore, disaster management training should be included in the basic education of nurses [30, 31].

Training programs for disaster response will enhance hospital personnel’s awareness of existing disaster management plans, increase employee participation in planning and problem-solving related to these programs, and improve employees’ skills in performing their assigned tasks [24]. Consequently, training and practice are effective methods for preparing personnel to respond to disasters and to face unexpected events [25, 26].

Skryabina et al. indicated that the main advantage of participating in the exercise and learning how to respond to an incident is that, considering the rarity of major incidents with mass casualties, simulation exercises are the only option for testing major incident programs. These exercises help keep response protocols up-to-date by enhancing skills and knowledge to improve response coordination through adherence to practiced incident plans, thereby increasing people’s confidence when responding [32].

Moss & Gaarder suggest that training is likely to boost employees’ self-confidence and make them feel more prepared. Practice should be tailored to the needs and potential challenges of each healthcare system [33].

Ugelvik et al. found significant gaps between prehospital rescue and emergency services in Norway regarding preparedness efforts. This highlights the need for national standards, minimum requirements, follow-up procedures for organizations, and future re-evaluations. The implementation of mandatory interdisciplinary training among fire/rescue, police, and emergency ambulance services appears to have been beneficial. Regular reviews of the standards can serve as a useful tool for evaluating and tracking mass casualty preparedness at the national, regional, and local levels [34].

Schulz et al. investigated the perceptions of first medical responders regarding mass casualty scenario training. Support for realistic scenarios, inter-agency collaboration, improved incident management skills, and thorough post-training evaluations are identified as important factors. Additionally, utilizing the potential of virtual reality technologies as a valuable tool for training significantly enhances the training experience [35].

Cocco & Thomas-Boaz, in their research, demonstrated that the lessons learned from preparedness assessments are closely related to those from actual incidents, highlighting the importance of these assessments. They play a crucial role, and exercises of any kind can effectively identify and improve opportunities while increasing preparedness. Mitigating interoperability issues during an emergency requires investment in training, planning, and preparedness, as well as routine mass casualty incident training and exercises that involve all affected departments and services throughout the hospital environment. Additionally, incorporating the principles of capacity management into hospital emergency plans is essential for maintaining the continuity of health center operations during a crisis [36].

Veenema et al. demonstrated that among different disciplines, nurses report the lowest level of knowledge and confidence. This indicates serious deficiencies in healthcare providers’ knowledge, skills, and self-perceived abilities to participate in a large-scale mass casualty event [37].

Ashkenazi et al. found that conducting exercises helps identify deficiencies in the hospital’s disaster plan, particularly in triage, emergency department management, and the appropriate use of resources such as radiology, operating rooms, and secondary patient transport. Having prior knowledge about disease diagnosis, identifying problems, and understanding the statistics of deficiencies, as well as specifying resources, enables accurate identification in clinical decision-making and effective resource management [38].

According to the results of the present study, accident and disaster managers must conduct training courses continuously in this field and implement limited operational exercises to improve the readiness of members of the incident command system and hospital staff, enabling them to respond effectively to accidents with mass casualties.

Limitations of the study included limitations in time and resources for implementing round table exercises, difficulty in coordinating and ensuring the participation of all key personnel due to military duties, and restrictions on access to sensitive and confidential information.

Conclusion

The tabletop exercises have a significant effect on enhancing the capabilities of the members of the incident command system and the hospital in managing disasters.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank the “Clinical Research Development Unit” of Baqiyatallah Hospital for its kind cooperation.

Ethical Permissions: This article is derived from the approved research project 402000006 at Baqiyatullah University of Medical Sciences (IR.BMSU.REC.1402.069). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. The confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were ensured by coding the questionnaires. Study participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Basiri A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (30%); Abbasi Farajzadeh M (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (25%); Mohammadian M (Third Author), Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Heidaranlu E (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer/Assistant Researcher (35%)

Funding/Support: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

In recent decades, major accidents and disasters have been increasing globally, including in Iran. The occurrence of these incidents affects more people every day, disrupts the provision of health services, and slows down the development process [1, 2]. In accidents with mass casualties, not only are a large number of individuals in the affected community injured, but such incidents also lead to physical, mental, and social disabilities [3, 4]. Mass casualty incidents are those, in which hospital emergency service resources, including staff and equipment, cannot adequately respond due to the number and severity of injuries [5]. Given the high demand for health services during accidents and disasters, having a plan for preparedness and response is essential for effective hospital risk management [6, 7]. Developing a preparedness plan that includes training for all employees and regular exercises, along with forecasting the necessary resources, is crucial for incident management response [8]. Capacity building in hospitals, as the primary providers of health services during incidents with a high number of injuries, is a priority for the health system [9].

Health sector employees are the first group to respond to accidents and disasters involving mass casualties; therefore, their level of preparedness and appropriate response is a critical factor in determining the rates of death and potential injuries during such events [10, 11]. Exercises provide practical learning opportunities and serve as an effective method for assessing and improving personnel performance in simulated conditions based on various scenarios. Exercises empower personnel by enhancing their ability to analyze information and make decisions [12, 13]. These exercises are conducted for different purposes, including training personnel, increasing individual capabilities and skills, and identifying weaknesses and needs. Exercises can be categorized in various ways; one common method divides them into two types, including discussion-based and performance-based [14]. Performance-based training involves a form of training that combines practical work. This type of exercise is designed to evaluate plans, policies, memorandums, and procedures, clarify roles and responsibilities, and identify resource deficiencies in an operational environment. Performance-based training includes three types of exercises, including functional training and full-scale training [14, 15]. Unfortunately, recent studies have indicated that healthcare workers are not adequately prepared to respond to accidents. Various studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of discussion-based exercises, including roundtable exercises, in mass casualty incidents. Abbasi Dolatabadi et al. identified a lack of knowledge and preparation as factors contributing to emotional stress during the execution of duties in crisis and disaster situations. They believe that preparedness to respond to disasters enhances healthcare workers’ self-confidence and reduces the extent of damage and vulnerability when facing unforeseen events [16]. Khankeh et al. highlighted the trained workforce as one of the facilitating factors in providing health services [17, 18]. Kang et al. reported that training healthcare workers has long been recognized as a crucial component of disaster preparedness [19]. Experiences also indicate that health workers are not only inadequately prepared to respond to incidents, but inconsistencies and parallel or conflicting actions have exacerbated the situation, revealing a gap in crisis management methods. A scientific review of past experiences shows that the primary weakness of crisis management in hospitals is intra-organizational inconsistency and lack of coordination among primary responders, depending on the type and severity of incidents during disasters. One significant challenge is the unfamiliarity of healthcare workers with team functions in the context of crisis management. Unfortunately, most functions occur in isolated “islands,” leading to inefficiencies and an excess of responsible parties and incident commanders. Previous experiences have demonstrated that conducting training and various exercises focused on coordination and team performance, particularly among the members of the incident command system in hospitals, has resulted in better outcomes in crisis management [17, 19].

Achieving coordination and coherence among the various members of the incident command system involved in incidents requires a solid foundation, one of the key elements of which is team training, exercises, and coordination. Unfortunately, the prevailing approach to training for groups involved in accidents tends to focus on single-professional methods, which not only fail to prepare them for effective team performance but also foster an individualistic mindset. In a consolidated review study, Jose & Dufrene investigated the most effective methods or educational approaches to enhance the ability of healthcare workers to respond to a crisis. Their findings, based on a review of more than 190 primary studies, indicated that the most effective educational approach in this context is the implementation of roundtable exercises and simulations. To provide an effective, coordinated, and organized response to the impacts of various types of disasters and emergencies, the existence of emergency operation plans (EOPs) is essential [20]. However, it is important to note that this program should not only exist theoretically but should also be validated in written form through the execution of different types of exercises. Exercises are activities conducted with the purpose of training and enhancing capabilities.

Since the selected military hospital is located in a strategic area of Tehran, and preparedness to respond to accidents and disasters is particularly important in this region, the present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of training on accident and disaster management based on a practical approach. The study focused on the ability of members of the hospital incident command system (HICS) to manage mass casualties in a selected military hospital in Tehran.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sample

The current semi-experimental research involved a single group, including 20 directorate, senior and middle managers, doctors, nurses, and health and emergency managers, assessed before and after a tabletop exercise scenario focused on incidents with mass casualties in Tehran in 2023. The statistical population consisted of the members of the HICS who (Table 1).

Table 1. The statistical population of the research

Study instrument

Data collection was conducted using a researcher-developed questionnaire, which underwent content and face validity assessments by ten experts. The questionnaire was designed to measure components of the hospital’s readiness regarding the HICS, overcapacity, and early warning system (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic information of experts and specialists in the content validity of the questionnaire

Data collection

After confirming the news of the accident and announcing the crisis code, the members of the HICS were summoned to the hospital’s command center by the commander. During the roundtable exercise, each process owner participating in the research was asked to describe their tasks. At the end of the roundtable exercise, the strengths and weaknesses, as well as the effectiveness of the training provided, were discussed through interaction, mutual thinking, and reflection.

The members of the HICS participated in a training workshop that included presentations on the theoretical foundations of crisis management and the HICS, along with descriptions of duties and the roles of the members defined in the HICS. To implement the roundtable exercise, the emergency operations center (EOC) of the University of Medical Sciences was informed of the incident by announcing the arrival of the injured at the news center, according to the prepared scenario. The intervention consisted of two two-day (4-hour) training workshops on accident and disaster risk management, which included presentations on the fundamentals of the HICS and a practical component involving the scenario-based roundtable exercise with the participation of the process owners.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected before and after the intervention using a standard questionnaire to assess readiness, both prior to and following the roundtable exercise (Figure 1). SPSS version 21 software was used for data analysis and data were expressed using descriptive statistics.

Figure 1. Flowchart of research execution method

Findings

This study involved 20 members of the HICS and assessed the components of the early warning system, the incident command system, overcapacity, and operational plans were examined in two dimensions, including preparation and response, both before and after the roundtable exercise. Despite the impact of desk training on the readiness of members of the HICS to manage incidents with mass casualties, the average percentage of readiness and response before the intervention was 44.5% and 36.11%, respectively. After the intervention involving desk training, the percentage of readiness increased to 77.5%, while the hospital’s response score rose to 72.22%, which increased by 33% for readiness and 36.11% for response (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. Preparation scores before the roundtable exercise

Table 4. Preparation scores after the roundtable exercise

In total, the hospital improved by 33% in the readiness index and 36.11% in the response index, indicating that the roundtable exercise was effective in enhancing the hospital’s preparedness in the face of accidents and disasters (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of the hospital’s readiness and response percentages before and after the intervention.

Discussion

This study was designed to determine the effect of educational interventions and tabletop exercises on the preparedness of healthcare workers at a selected military hospital in Tehran to handle incidents involving mass casualties. Approximately half of the healthcare workers (48%) had faced crises and disasters, and 65.3% of nurses reported that they had received training in disaster response. However, most of them (92%) felt that they needed additional training, which may indicate that the training provided was either ineffective and insufficient or not delivered at the appropriate time.

In the study by Pek et al., evaluation outcomes across full-scale exercises are different, leading to challenges in consolidating the effectiveness of simulations into a single measure [21]. It is recommended that best evidence-based practices for simulation be adhered to in full-scale exercises so that training can translate into better outcomes for casualties during actual disasters or mass-casualty incidents. Additionally, the reporting of simulation use in full-scale exercises should be standardized using a framework, and the evaluation process should be rigorous to determine and compare effectiveness across full-scale exercises [21, 22].

In the study by Al-Romaihi et al., the evaluation outcomes indicated that the overall mean knowledge score regarding communicable disease (CD) threats among study participants is 75.0%, with the majority of participants having a favorable attitude toward CD preparedness during mass gatherings (MG) events. Participants achieved high scores in workshops on triaging, first aid, and infection control. Additionally, study participants had positive perceptions of the current preparedness of their respective hospitals to respond to CD outbreaks during MG events [23, 24].

Teng-Calleja et al. showed that the overall scores in the areas of knowledge, attitude, and performance increased significantly after the intervention compared to before [25, 26]. Xia et al. reported that students receiving the program display greater increases in knowledge and skills related to disaster preparedness than those in the control group. One month after the intervention, the experimental group still demonstrated significantly higher levels of disaster knowledge and skills than the control group. There were no statistically significant differences over time in attitude measures. This program enhanced students’ abilities, and the findings can serve as a basis for further developing public health education for all nurses. Chinese leaders of public health institutions and nursing administrators can create guidelines for public health nursing (PHN) competencies and prepare the public health nursing workforce to be effective in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery [27].

Nejadshafiee et al. indicated that the majority of experts (76%) assess the necessity of training and developing the required capabilities in nurses for handling accidents and disasters and caring for the injured as “very high,” while 23.53% rate it as “high” [28]. In the study by Mulyasari et al., the evaluation outcomes regarding the level of healthcare in dealing with disasters are reported to be average [29]. Fung et al. found that nurses in Hong Kong are not adequately prepared for disasters but are aware of the need for such preparation. Therefore, disaster management training should be included in the basic education of nurses [30, 31].

Training programs for disaster response will enhance hospital personnel’s awareness of existing disaster management plans, increase employee participation in planning and problem-solving related to these programs, and improve employees’ skills in performing their assigned tasks [24]. Consequently, training and practice are effective methods for preparing personnel to respond to disasters and to face unexpected events [25, 26].

Skryabina et al. indicated that the main advantage of participating in the exercise and learning how to respond to an incident is that, considering the rarity of major incidents with mass casualties, simulation exercises are the only option for testing major incident programs. These exercises help keep response protocols up-to-date by enhancing skills and knowledge to improve response coordination through adherence to practiced incident plans, thereby increasing people’s confidence when responding [32].

Moss & Gaarder suggest that training is likely to boost employees’ self-confidence and make them feel more prepared. Practice should be tailored to the needs and potential challenges of each healthcare system [33].

Ugelvik et al. found significant gaps between prehospital rescue and emergency services in Norway regarding preparedness efforts. This highlights the need for national standards, minimum requirements, follow-up procedures for organizations, and future re-evaluations. The implementation of mandatory interdisciplinary training among fire/rescue, police, and emergency ambulance services appears to have been beneficial. Regular reviews of the standards can serve as a useful tool for evaluating and tracking mass casualty preparedness at the national, regional, and local levels [34].

Schulz et al. investigated the perceptions of first medical responders regarding mass casualty scenario training. Support for realistic scenarios, inter-agency collaboration, improved incident management skills, and thorough post-training evaluations are identified as important factors. Additionally, utilizing the potential of virtual reality technologies as a valuable tool for training significantly enhances the training experience [35].

Cocco & Thomas-Boaz, in their research, demonstrated that the lessons learned from preparedness assessments are closely related to those from actual incidents, highlighting the importance of these assessments. They play a crucial role, and exercises of any kind can effectively identify and improve opportunities while increasing preparedness. Mitigating interoperability issues during an emergency requires investment in training, planning, and preparedness, as well as routine mass casualty incident training and exercises that involve all affected departments and services throughout the hospital environment. Additionally, incorporating the principles of capacity management into hospital emergency plans is essential for maintaining the continuity of health center operations during a crisis [36].

Veenema et al. demonstrated that among different disciplines, nurses report the lowest level of knowledge and confidence. This indicates serious deficiencies in healthcare providers’ knowledge, skills, and self-perceived abilities to participate in a large-scale mass casualty event [37].

Ashkenazi et al. found that conducting exercises helps identify deficiencies in the hospital’s disaster plan, particularly in triage, emergency department management, and the appropriate use of resources such as radiology, operating rooms, and secondary patient transport. Having prior knowledge about disease diagnosis, identifying problems, and understanding the statistics of deficiencies, as well as specifying resources, enables accurate identification in clinical decision-making and effective resource management [38].

According to the results of the present study, accident and disaster managers must conduct training courses continuously in this field and implement limited operational exercises to improve the readiness of members of the incident command system and hospital staff, enabling them to respond effectively to accidents with mass casualties.

Limitations of the study included limitations in time and resources for implementing round table exercises, difficulty in coordinating and ensuring the participation of all key personnel due to military duties, and restrictions on access to sensitive and confidential information.

Conclusion

The tabletop exercises have a significant effect on enhancing the capabilities of the members of the incident command system and the hospital in managing disasters.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank the “Clinical Research Development Unit” of Baqiyatallah Hospital for its kind cooperation.

Ethical Permissions: This article is derived from the approved research project 402000006 at Baqiyatullah University of Medical Sciences (IR.BMSU.REC.1402.069). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. The confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were ensured by coding the questionnaires. Study participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' Contribution: Basiri A (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (30%); Abbasi Farajzadeh M (Second Author), Methodologist/Statistical Analyst (25%); Mohammadian M (Third Author), Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (10%); Heidaranlu E (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer/Assistant Researcher (35%)

Funding/Support: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Mahdi SS, Jafri HA, Allana R, Battineni G, Khawaja M, Sakina S, et al. Systematic review on the current state of disaster preparation simulation exercises (SimEx). BMC Emerg Med. 2023;23(1):52. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12873-023-00824-8]

2. Carenzo L, Ingrassia PL, Foti F, Albergoni E, Colombo D, Sechi GM, et al. A region-wide all-hazard training program for prehospital mass casualty incident management: A real-world case study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;17:e184. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2022.84]

3. Ebadi A, Heidaranlu E. Virtual learning: A new experience in the shadow of coronavirus disease. Shiraz E Med J. 2020;21(12):e106712. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/semj.106712]

4. Kman NE, Price A, Berezina‐Blackburn V, Patterson J, Maicher K, Way DP, et al. First responder virtual reality simulator to train and assess emergency personnel for mass casualty response. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2023;4(1):e12903. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/emp2.12903]

5. Yánez Benítez C, Tilsed J, Weinstein ES, Caviglia M, Herman S, Montán C, et al. Education, training and technological innovation, key components of the ESTES-NIGHTINGALE project cooperation for mass casualty incident preparedness in Europe. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2023;49(2):653-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00068-022-02198-1]

6. Jung Y. Virtual reality simulation for disaster preparedness training in hospitals: Integrated review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e30600. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/30600]

7. Heidaranlu E, Ebadi A, Ardalan A, Khankeh H. A scrutiny of tools used for assessment of hospital disaster preparedness in Iran. Am J Disaster Med. 2015;10(4):325-38. [Link] [DOI:10.5055/ajdm.2015.0215]

8. Biswas S, Bahouth H, Solomonov E, Waksman I, Halberthal M, Bala M. Preparedness for mass casualty incidents: The effectiveness of current training model. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;16(5):2120-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2021.264]

9. Montán KL, Örtenwall P, Blimark M, Montán C, Lennquist S. A method for detailed determination of hospital surge capacity: A prerequisite for optimal preparedness for mass-casualty incidents. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2023;49(2):619-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00068-022-02081-z]

10. Tovar MA, Zebley JA, Higgins M, Herur-Raman A, Zwemer CH, Pierce AZ, et al. Exposure to a virtual reality mass-casualty simulation elicits a differential sympathetic response in medical trainees and attending physicians. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2023;38(1):48-56. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X22002448]

11. Heidaranlu E, Amiri M, Salaree MM, Sarhangi F, Saeed Y, Tavan A. Audit of the functional preparedness of the selected military hospital in response to incidents and disasters: Participatory action research. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(1):168. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12873-022-00728-z]

12. Taschner MA, Nannini A, Laccetti M, Greene M. Emergency preparedness policy and practice in Massachusetts hospitals. Workplace Health Saf. 2017;65(3):129-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2165079916659505]

13. Gardner AK, DeMoya MA, Tinkoff GH, Brown KM, Garcia GD, Miller GT, et al. Using simulation for disaster preparedness. Surgery. 2016;160(3):565-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.surg.2016.03.027]

14. Langan JC, Lavin R, Wolgast KA, Veenema TG. Education for developing and sustaining a health care workforce for disaster readiness. Nurs Adm Q. 2017;41(2):118-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000225]

15. Rahmati-Najarkolaei F, Moeeni A, Ebadi A, Heidaranlu E. Assessment of a military hospital's disaster preparedness using a health incident command system. Trauma Mon. 2017;22(2):e31448. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.31448]

16. Abbasi Dolatabadi Z, Zakerimoghadam M, Bahrampouri S, Jazini A, Nabi Foodani M. Challenges of implementing correct triage: A systematic review study. J Mil Med. 2022;24(2):1096-105. [Persian] [Link]

17. Khankeh HR, Lotfolahbeygi M, Dalvandi A, Amanat N. Effects hospital incident command system establishment on disaster preparedness of Tehran hospitals affiliated to law enforcement staff under simulated conditions. Health Emerg Disasters Q. 2018;3(4):207-14. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/hdq.3.4.207]

18. Heidaranlu E, Bagheri M, Moayed MS. Assessing the preparedness of military clinical nurses in the face of biological threats: With a focus on the COVID-19 disease. J Mil Med. 2022;24(6):1419-26. [Persian] [Link]

19. Kang JS, Lee H, Seo JM. Relationship between nursing students' awareness of disaster, preparedness for disaster, willingness to participate in disaster response, and disaster nursing competency. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;17:e220. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2022.198]

20. Jose MM, Dufrene C. Educational competencies and technologies for disaster preparedness in undergraduate nursing education: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(4):543-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.021]

21. Pek JH, Quah LJJ, Valente M, Ragazzoni L, Della Corte F. Use of simulation in full-scale exercises for response to disasters and mass-casualty incidents: A scoping review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2023;38(6):792-806. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1049023X2300660X]

22. Heidaranlu E, Habibi F, Moradi A, Lotfian L. Determining functional preparedness of selected military hospitals in response to disasters. Trauma Mon. 2020;25(6):249-53. [Link]

23. Al-Romaihi H, Al-Dahshan A, Kehyayan V, Shawky S, Al-Masri H, Mahadoon L, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and training of health-care workers and preparedness of hospital emergency departments for the threat of communicable diseases at mass gathering events in Qatar: A cross-sectional study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021;17:e49. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2021.296]

24. Heidaranlu E, Tavan A, Aminizadeh M. Investigating the level of functional preparedness of selected Tehran hospitals in the face of biological events: A focus on COVID-19. Int J Disaster Resil Built Environ. 2022;13(2):150-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/IJDRBE-08-2021-0088]

25. Teng-Calleja M, Presbitero A, De Guzman MM. Dissecting HR's role in disaster preparedness and response: A phenomenological approach. Pers Rev. 2024;53(2):455-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1108/PR-12-2021-0867]

26. Heidaranlu E, Khankeh H, Ebadi A, Ardalan A. An evaluation of non-structural vulnerabilities of hospitals involved in the 2012 east Azerbaijan earthquake. Trauma Mon. 2017;22(2):e28590. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/traumamon.28590]

27. Xia R, Li S, Chen B, Jin Q, Zhang Z. Evaluating the effectiveness of a disaster preparedness nursing education program in Chengdu, China. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37(2):287-94. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/phn.12685]

28. Nejadshafiee M, Sarhangi F, Rahmani A, Salari MM. Necessity for learning the knowledge and skills required for nurses in disaster. Educ Strateg Med Sci. 2016;9(5):328-34. [Persian] [Link]

29. Mulyasari F, Inoue S, Prashar S, Isayama K, Basu M, Srivastava N, et al. Disaster preparedness: Looking through the lens of hospitals in Japan. Int J Disaster Risk Sci. 2013;4(2):89-100. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13753-013-0010-1]

30. Fung OW, Loke AY, Lai CK. Disaster preparedness among Hong Kong nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(6):698-703. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04655.x]

31. Heidaranlu E, Moayed MS, Parandeh A. Spiritual-cultural needs as the main causative factor of death anxiety in Iranian COVID-19 patients: A qualitative study. J Relig Health. 2024;63(1):817-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10943-023-01972-8]

32. Skryabina EA, Betts N, Reedy G, Riley P, Amlôt R. The role of emergency preparedness exercises in the response to a mass casualty terrorist incident: A mixed methods study. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;46:101503. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101503]

33. Moss R, Gaarder C. Exercising for mass casualty preparedness. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(2):e67-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.016]

34. Ugelvik KS, Thomassen Ø, Braut GS, Geisner T, Sjøvold JE, Agri J, et al. Evaluation of prehospital preparedness for major incidents on a national level, with focus on mass casualty incidents. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2024;50(3):945-57. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00068-023-02386-7]

35. Schulz F, Nguyen Q, Baetzner A, Sjöberg D, Gyllencreutz L. Exploring medical first responders' perceptions of mass casualty incident scenario training: A qualitative study on learning conditions and recommendations for improvement. BMJ Open. 2024;14(7):e084925. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2024-084925]

36. Cocco C, Thomas-Boaz W. Preparedness planning and response to a mass-casualty incident: A case study of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. J Bus Contin Emerg Plan. 2019;13(1):6-21. [Link] [DOI:10.69554/OQTK6473]

37. Veenema TG, Boland F, Patton D, O'Connor T, Moore Z, Schneider-Firestone S. Analysis of emergency health care workforce and service readiness for a mass casualty event in the Republic of Ireland. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13(2):243-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2018.45]

38. Ashkenazi I, Ohana A, Azaria B, Gelfer A, Nave C, Deutch Z, et al. Assessment of hospital disaster plans for conventional mass casualty incidents following terrorist explosions using a live exercise based upon the real data of actual patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2012;38(2):113-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00068-011-0154-x]