Volume 15, Issue 4 (2023)

Iran J War Public Health 2023, 15(4): 453-461 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

Ethics code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1401.211

History

Received: 2023/12/9 | Accepted: 2024/03/29 | Published: 2024/05/7

Received: 2023/12/9 | Accepted: 2024/03/29 | Published: 2024/05/7

How to cite this article

Ezzati Rastegar K, Khoshravesh S, Behzad G, Khazaei S, Soltanian A. Iranian Viewpoints on the Dimensions of Perceived Social Support during the COVID-19 Pandemic; a Qualitative Study. Iran J War Public Health 2023; 15 (4) :453-461

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1421-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1421-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

2- Health Education and Health Promotion, Health Center of Tuyserkan, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

3- Modeling of Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

2- Health Education and Health Promotion, Health Center of Tuyserkan, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

3- Modeling of Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (618 Views)

Introduction

The extensive effects of COVID-19 have disrupted various aspects of people's daily lives, such as healthcare and economic and social aspects [1]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, a serious global health concern, has greatly affected the mental health status of people around the world [2]. The results of a recent umbrella review indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the creation of many mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, mood disorders, psychological distress, post-traumatic stress disorder, insomnia, fear, stigmatization, low self-esteem, and lack of self-control [3]. Other adverse mental health outcomes have also been reported, such as emotional disturbances and suicidal behaviors [4].

Evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has been identified as a stressor [2]. Perceived social support can act as a protector against negative mental health impacts from COVID-19 [5]. Perceived social support plays an important role in reducing adverse impacts of events on people and can improve mental health [6]. Perceived social support is the level of perceived support for the family, groups, and society in the face of psychological pressures [7]. Social support could help individual mental health by providing the resources needed to deal with life's challenges [5].

There are four categories of social support in the literature. These types include emotional (i.e., providing empathy, kindness, love, hope, and caring), instrumental (i.e., providing tangible help and services that directly assist a person), informational (i.e., providing guidance, suggestions, and material that a person can use to address problems), and appraisal (i.e., providing information that is useful for self-evaluation purposes or constructive feedback and affirmation) supports [8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the adaption of some health policies, such as lockdowns and isolation for preventing disease transmission, has led to restricting the mobility, social interactions, and daily activities of people [3]. Despite the positive consequences of implementing health policies during the outbreak of COVID-19, these policies have also had negative effects at the community level [9]. For this reason, the recent epidemic has encouraged countries worldwide to consider supportive policies to protect their societies, including supporting employment, providing unemployment benefits, and creating social programs for vulnerable working groups. To comply with social distancing, insurance organizations utilize a variety of service delivery models (e.g., more use of digital channels, call centers to provide services to people, etc.). Universities and educational institutions have also had to change their educational systems, so in some countries, the education system has even changed to virtual space [10].

Although the outbreak of COVID-19 has impacted every country in the world, some countries have implemented accurate and timely policies that have caused minimal damage. For instance, what has been observed in China and its policies in support of disease prevention and control have been relatively successful in controlling the disease by adopting isolation and lockdown policies despite the influx of people [11].

In some countries, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching impacts. In the area of employment in Iran, macro surveys show that some individuals have not only lost their jobs due to COVID-19, but in addition to not having insurance, they had no access to government facilities and financial assistance. Although the government's support for managing labor supply and demand markets and support programs has been somewhat effective in this field [12]. Thus, given what has been mentioned, an important point for governments to consider when implementing health policies is to focus on the dimensions and problems caused by emerging diseases such as COVID-19. Social support and help to resolve the damage caused by COVID-19 should be placed in the work priorities of governments.

Therefore, the fundamental issues that arise in those areas for society members are how much people know about the support provided by the government and national and provincial policymakers and how much such support is tangible and could be implemented. Since no such research has been done in this field in Iran, it seems necessary to know the views of people from different professions regarding the perceived support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the perceived social support of Hamadan citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants and Methods

This content analysis qualitative study was conducted from September to December 2022 in the Hamadan province; 42 in-depth semi-structured interviews were completed with men and women residents. Eligible participants were adults over 18 and heads of household. They were physically and mentally capable of participating in this study and gave informed consent.

Participants were selected from different occupational groups. They were informed about the study objectives and procedures, and a consent form was signed if they agreed to participate. Once eligibility was established, an appointment was made for interviews. Before the start of each interview, the intended usage of an audiotape machine to record the interviews was explained to the study participants. We asked about demographic information, including age, marital situation, employment status, and level of education (warm-up questions). Interviews explored social support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interviews explored individuals' perceptions of social and occupational support during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research question guiding this exploration was:

1. What problems did you have in getting the right information about the disease during COVID-19?

2. What problems did you have in getting the right information in your job development?

3. What new crises did you encounter during the COVID-19 pandemic?

4. What psychological and emotional wounds did you have during the COVID-19 disease?

5. What financial losses did you have during the COVID-19 pandemic?

6. How did you manage your financial needs?

7. How did you evaluate your life conditions?

8. How did your family and others evaluate your job situation?

All interviews were conducted in a private room by two of the researchers. Each face-to-face interview lasted approximately 30 minutes. Interviewers were familiar with the local language, and all interviews were conducted in the local languages predominantly spoken in the study area. The researchers had previous training and experience in qualitative interview techniques and qualitative research procedures. We confirmed that all data would remain confidential and they could stop the interview or skip questions they did not like answering. One researcher asked questions, while the research assistant managed the audio equipment and took notes during the interview. Interview and sampling were continued until saturation was achieved. Also, researchers increased the credibility of the data by establishing a close rapport with participants and double-checking the notes and recorded transcripts.

The research team transcribed all interviews verbatim and double-checked the transcripts for accuracy. The team chose a qualitative content analysis approach to identify and investigate occupational and social support [13]. We conducted this approach in three steps preparation (researchers tried to make sense of the data. The goal was to immerse in the data, which is why the writings were read several times), organizing (process of open coding and creating categories, grouping codes, and, formulating an overall description of the research issues via making abstract categories and subcategories), and, reporting (interpretation, to which texts are to be placed under similar categories and subcategories). These techniques were employed, and the results of the coding process were documented to help construct a coherent category system.

Findings

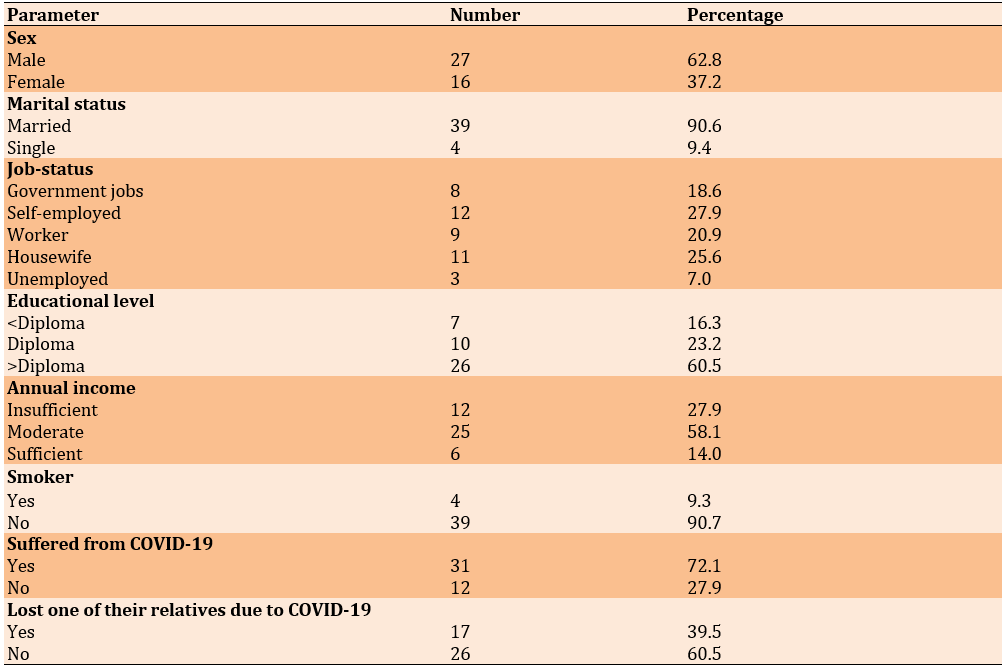

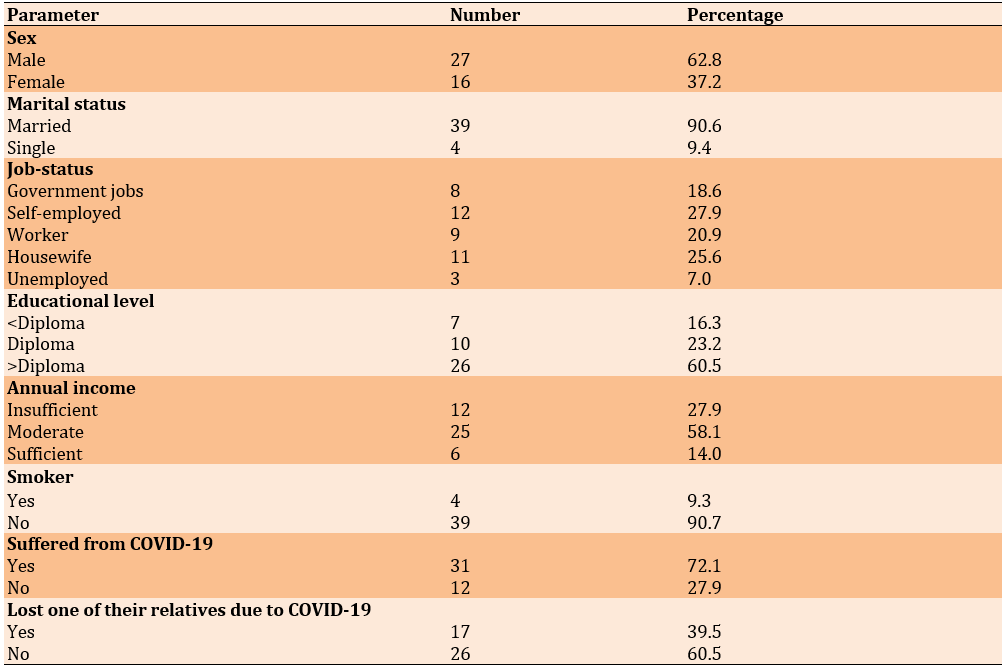

The sample included 62.8% males and 37.2% females. The mean age of the participants was 39.85±9.57 (24 to 65 years). The mean of the participants’ households was 3.38±1.28 (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of the participants

Social support is the functional content of relationships which can be categorized into four types of supportive behavior or action:

Emotional

Emotional support provides affection, kindness, and attention to another person and ensures the person feels valued and noticed. In this regard, the participants’ claims showed that they received the highest support from their families.

Participant No. 5 (male, hairdresser, 32 years) stated:

“I have a very close relationship with customers because of my job, which was dangerous during the COVID-19 times. Nevertheless, my wife was kind to me like before. She was not worried if I spread the disease in the house”.

Participant No. 32 (male, worker, 35 years) claimed:

“Although my job status experienced recession and seasonal jobs were low and also, I am a tenant and do not have much income, my wife and my parents always told me: Everything will be alright. Also, they expected me to spend less money”.

However, the participants sometimes talked about the lack of attention from family and relatives.

Participant No. 4 (male, shop owner, 28 years) stated:

“We were among the businesses that had to close the shop during the COVID-19 times. That was why we stayed home. Sometimes, I had arguments with my wife as if we were used to seeing each other only at night”.

Participant No. 15 (female, hairdresser, 34 years) said:

“Honestly, I complained to my husband why he came home late but during the COVID-19 times that we both had to stay home, we felt that we were fed up with each other, so we had quarrels with each other under different excuses. I can say that we were all anxious.”

Informational

Information support provides consultation, suggestions, and information that a person can use to solve problems. This kind of support occurs when a person helps another person understand a stressful situation better and determines which source and coping strategy are required to face that situation. Most participants sought appropriate information during the COVID-19 crisis and acquired information from official and unofficial channels.

Participant No. 17 (male, baker, 31 years) stated:

“We were one of the businesses that should not have been closed, and just God knows what difficulties we went through. Every day, we hear different information. We did not know whether to believe the TV news or social media”.

Another participant (male, bank clerk, 39 years) stated:

“We were in danger because of our customers and the closed atmosphere of the bank. I got infected with COVID-19. Sometimes, the information was scary but nowhere could be reliable except the health centers and hospitals. They worked as much as they could and provided us with the right information as well”.

A housewife stated:

“I would sit in front of the TV all day to see what we had to do. I tried to comply with all the orders they gave. But sometimes I heard things from friends and neighbors and could not distinguish who told the truth”.

Instrumental

Instrumental support provides tangible aids such as services, financial aid, and other specific goods. This type of support includes aid for the shortage of financial resources such as money and accommodation or may solve daily life problems such as child care, housework, etc. Regarding the COVID-19 crisis, most participants had encountered financial problems, according to their statements. Instrumental support was categorized into two areas of support from family, friends, guilds, and government.

Participant No. 32 (male, driver, 45 years) expressed:

"I pay installments for my car. If I do not work, I can pay the installments aside from the extra costs of the car like tires or gas. There were fewer passengers because of the limitations and our income had reduced. The :union: did not help at all and I did not know what to do with my installments”.

Participant No. 39 (housewife, 52 years) said:

"My husband had rented a fast-food stand with his friend. We are also a tenant. When our shop was closed during the lockdown times, our conditions got worse as well. We had heard that the tenants and loan receivers would be given a grace time during the COVID-19 era, but it was not true and we lived with difficulty”.

Another participant (female, housewife, 24 years) stated:

“At the beginning of the COVID-19 days, they said hospitals and health centers supplied masks and disinfectants. We referred to those places several times but they said that was not true. Masks and disinfectants were expensive and rare”.

Meanwhile, a 26-year-old female teacher stated the problem in another way:

“It is true that I was a government employee and had a fixed annual salary, but COVID-19 turned classes online. It was not possible to supply a phone or tablet for my child. I had even students who could not buy a phone and it was difficult to teach them. Phone or tablet was not the only problem. Internet problems and the lack of a good program were other problems which that all families were coping with. Support was presented in a different way in terms of support from family and relatives”.

Participant No. 3 (male, jewelry seller, 36 years) claimed:

"The market works with checks and securities. People referred to the market less and bought less. I had checks as well. I asked everyone I knew to help me but they did not even those to whom I had lent money before when they had problems”.

However, another participant (male, mechanic, 53 years) stated:

"We had also financial problems like all other businesses. We had to use our savings. When the savings were over, my father and brothers helped me".

Appraisal

Appraisal support provides useful information for self-evaluation. In other words, feedback from others on performance can result in improvement. The participants in the present study reported various appraisal supports.

Participant No. 18 (30 years, marketer) said:

“We had to communicate with production and sales units because of our job conditions. We referred to electronic advertising and services when some businesses were down due to COVID-19. Actually, the customers were satisfied and we developed our services. At least, we could reduce many transportation costs".

Another participant (male, computer services, 24 years) stated:

"COVID-19 greatly helped the computer service businesses. Although the businesses were closed, we could provide services out of the office. Most organizations and companies required offline services and that was in our favor. Our customers were also satisfied and it gave a good feeling, I mean both customer satisfaction and more profits”.

On the other hand, some businesses did not receive good feedback during the COVID-19 period.

Participant No. 15 (male, teacher, 45 years) explained:

"Online education was not what we thought. The problems related to phones, tablets, and the internet on the one hand and the major problems of dissatisfaction with education on the other hand. The inadequate and unfavorable activity of students meant the poor performance of the teacher. We did not have any good feedback as we tried and this is an alarm”.

Another employee said:

"They changed the working hours during the COVID-19 times and some personnel worked either part-time or remotely. This process was not very appropriate. The customers were the same but we faced problems with our tasks. The customers were not satisfied at all. I had to do my colleague's duties as well during the working day and I was not very successful at all, or on the day when my colleague worked instead of me, he did not do the job as he had to”.

Discussion

The present study's findings showed that the social support perceived by our study participants during the COVID-19 pandemic was classified into four categories: Informational support, emotional support, instrumental support, and appraisal support.

The evidence indicates that people benefiting from various types of social support are in better health conditions than people without social support, and as these supports increase, mental health also increases, and the incidence of clinical disorders decreases [14].

The participants of our study stated that due to facing a newly emerging disease and the stressful situation of this disease, they tried to obtain information from various official and unofficial channels to learn more about the disease and its details. In the early stages of a crisis, the informational support of the public population is vital [15]. Informational support included reference/referral, advice, feedback/opinion, facts, personal experience, and perceptual knowledge [16, 17]. The results of a study in Iran revealed that many of the participants stated the use of social networks in information and education to increase public awareness in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic to be very effective and believed that social networks could be a suitable platform for information, education, and awareness [18] and a study in Taiwan showed that the most used sources of information related to COVID-19 in the studied subjects were the internet, traditional media, and family members respectively [19]. In Iran, official internet news agencies, traditional media, doctors, and healthcare personnel were the most important sources of information about COVID-19 [20]. Regarding information support, it is important that correct and reliable information is available to the public. Although the spread of the pandemic and the information related to COVID-19 spread on different media platforms, the infodemic was a big challenge in the recent pandemic [21]. In the present study, the participants stated that in addition to the need to obtain information, they also needed reliable information support; Because sometimes contradictory information was published in mass media and virtual space, which confused the people. As the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak, the world was quickly confronted with an overwhelming amount of true and false information that made it difficult to find reliable information for the people who needed it, what is termed by the World Health Organization as infodemics [22, 23]. The main information challenges this society faced during COVID-19 included the lack of a scientific reference source to access accurate information and the existence of a large amount of information in virtual networks, which led to confusion among people in society [21]. The main reason for the infodemic is the increase in people's access to the internet and social media, which in a short time gives a person a huge amount of information, which may be only a part of this reliable information [22]. Infodemics can have very bad effects on pandemics, such as making it difficult to access reliable sources and documents for the general population and health policymakers, increasing negative psychological consequences, including creating feelings of anxiety and depression in the general population, and delays in quick decisions and the inability of officials to control the published content [23]. During pandemics, policymakers must carefully consider the quality of information disseminated through different sources. In addition, when disseminating urgent health information, various and reliable sources should be used to ensure that different populations have access to critical knowledge [24].

Also, our participants stated that the healthcare system supported the citizens more than other sources of information, so this source was more reliable for the citizens. A national study in Japan showed that although television was the most used source of information, doctors and nurses were the most reliable sources of information [25].

Evidence shows that emotional support during a crisis can be very helpful in relieving general emotions [15]. The results of our study showed that most of the participants had received emotional support from their families during the pandemic. Family support is very important in times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The family can provide peace and control the emotions of family members (both sick and healthy members) by creating a safe place [26]. The participants of the study stated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, they had anxiety and worry due to contracting the disease and transmitting it to family members. Available evidence proves that isolation from family, relatives, and friends, deprivation of psychological support during hospitalization, worry about other family members getting sick, and social stigma caused by getting sick significantly increase anxiety in patients [27, 28]. Another study disclosed that due to the high prevalence of anxiety and depression in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, more family support for sick people prevents the transformation of these symptoms into long-term mental disorders [29]. The types of social support of the family for the affected people lead to the recovery of those affected by COVID-19. However, the strongest component related to the recovery of the patients was the family's emotional support [26]. The results of a multinational cross-sectional survey have confirmed that the lack of emotional support is mentioned as an independent risk factor for developing psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression during the recent pandemic [30]. Some of the citizens of our study also reported that they had not received any emotional support from their family and friends. These people believed that during COVID-19, staying at home caused frequent family arguments and bothered the family members. Considering the nature of the spread of the disease, one of the disease control policies was home quarantine, which caused family members to spend more time together at home during the outbreak of COVID-19. In this era, fear of illness, fear of death, the spread of false news and rumors, interference in daily activities, prohibitions or restrictions on travel and transit, reduction of social relations, and the occurrence of job and financial problems were threatening the mental health of families [31]. So, when families experience stress caused by negative life events, their adaption decreases [32]. This can cause dysfunctional responses in family members, leading to the formation and intensification of family conflicts [33]. Of course, we should not neglect the effect of the heavy use of social networks in this era. On the one hand, increasing the time spent using social networks during lockdown negatively affects couples' relationships and feelings towards each other and strengthens self-infatuation; on the other hand, it leads to various communication problems, reducing positive feelings of couples and marital conflicts [34]. The evidence shows that in epidemics, a healthy relationship, effective communication, positive thinking, and emotional support can create a more adaptive response to the crisis [35].

Most of the participants reported that they faced financial problems during the COVID-19 crisis. These problems included postponement of house and shop rents, inability to repay loans, bounced bank checks, reduced monthly income due to frequent holidays, use of savings for daily living, increasing in household health expenses, such as the costs of buying masks and disinfectants, the need to purchase smartphones/tablets and internet to participate in virtual classes.

A study in Chile confirmed that during the pandemic, unemployment and loss of income predicted the experience of many financial problems, such as reduced savings, problems in paying bills, debt, and mortgage loans [36]. The participants of the present study also stated that although they were sometimes financially supported by their families, despite the financial problems, they were not given any financial support by the :union:. In other words, considering the existing financial problems, the study participants expected the :union:s to adopt supportive policies in this field. Han's study in the USA indicated that :union: workers had more job security than non-:union: workers and received more pay for the hours they did not work due to COVID-19 [37]. Evidence proves that financial problems during the pandemic caused psychological problems in different populations, especially vulnerable populations [36, 38]. One of the coping strategies for managing psychological problems related to financial problems during the pandemic is to facilitate social support, improving public health facilities and improving health insurance, financial support for pregnant women and child care, special care for the elderly, and adopting policies to revive damaged businesses and strengthen entrepreneurs [38].

In the field of appraisal support, the study participants stated that they had received different feedback from others regarding their performance. For example, the participants with jobs that could provide services electronically expressed a tendency towards electronic services and advertising. Its expansion caused more profit and increased customer satisfaction.

Lockdown and the need for social distancing as policies adopted during the pandemic caused significant changes in online shopping, introducing digital payment systems, remote work, and electronic service delivery [39]. Evidence shows that the quality of electronic services is the key to achieving customer satisfaction [40]. It seems that in different communities, with the spread of COVID-19, the provision of electronic services has been developed, leading to customer satisfaction.

Some participants also believed that during COVID-19, education in the virtual space caused dissatisfaction among both students and teachers with the teaching method. In the era of COVID-19, one of the important changes in the education field worldwide was virtual education instead of face-to-face education [41]. This sudden change brought many challenges for people involved in education [42]. Teachers faced challenges implementing online education due to insufficient training with digital tools, lack of constant contact with students to monitor their study routine, and lack of support and help from parents [43]. A national study of medical students showed that despite the high flexibility of online education platforms, family distractions and poor internet connection were major problems with using these platforms [44]. The result of a study in Iran regarding the problems of online education also reported that the problems of virtual education from the teachers' point of view include the harm of excessive use of the internet by students, the problems of the special network for students, and digital resources, the violation of educational justice, the lack of basic facilities, the problems of the teaching-learning process, job pressure, parents' non-cooperation and low media literacy and from the parents' view included lack of basic facilities, damages of excessive use of the internet, reduction of teacher's efficiency, interruption in student's personality development, reduction of motivation, disruption of home order and unfamiliarity with the elements and educational skills of parents [45]. On the one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic increased the beneficiaries' skills and educational experience. On the other hand, it caused physical and mental disorders, academic failure, and job burnout [46]. Considering the challenges of virtual education, it seems that this issue will be developed in the future with the design of coherent and effective infrastructures, fundamental revision of human, financial, and support resources and lead to productivity.

In this study, telecommuting of employees in different departments caused disruptions in the performance of their work duties and reduced client satisfaction. With the spread of COVID-19, various organizations had to quickly train their employees to perform their work duties online and at home while maintaining productivity. Many employees faced difficulties adapting to online work, combining work hours with daily tasks, family commitments, information security, and privacy [47]. The benefits of telecommuting working in Indonesian teachers include more flexibility, no tracking of work hours, no travel expenses, reduced stress levels, and more free time. However, reduced work motivation was reported as a disadvantage [48]. Russian employees have perceived remote work as a positive experience [49]. Remote work can be a short-term and long-term answer to urban issues and emergency conditions. However, remote work has not yet become mainstream in modern human life [50].

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic has shed light on global crises' irrefutable mental and social health repercussions. Crucially, this pandemic highlighted the detrimental impact on households' jobs and incomes.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful to all those who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethical Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (IR.UMSHA.REC.1401.211).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contributions: Ezzati Rastegar K (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Khoshravesh S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Behzad G (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (10%); Khazaei S (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Soltanian AR (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: The authors thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for support (No. 140103171646).

The extensive effects of COVID-19 have disrupted various aspects of people's daily lives, such as healthcare and economic and social aspects [1]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, a serious global health concern, has greatly affected the mental health status of people around the world [2]. The results of a recent umbrella review indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the creation of many mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, mood disorders, psychological distress, post-traumatic stress disorder, insomnia, fear, stigmatization, low self-esteem, and lack of self-control [3]. Other adverse mental health outcomes have also been reported, such as emotional disturbances and suicidal behaviors [4].

Evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has been identified as a stressor [2]. Perceived social support can act as a protector against negative mental health impacts from COVID-19 [5]. Perceived social support plays an important role in reducing adverse impacts of events on people and can improve mental health [6]. Perceived social support is the level of perceived support for the family, groups, and society in the face of psychological pressures [7]. Social support could help individual mental health by providing the resources needed to deal with life's challenges [5].

There are four categories of social support in the literature. These types include emotional (i.e., providing empathy, kindness, love, hope, and caring), instrumental (i.e., providing tangible help and services that directly assist a person), informational (i.e., providing guidance, suggestions, and material that a person can use to address problems), and appraisal (i.e., providing information that is useful for self-evaluation purposes or constructive feedback and affirmation) supports [8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the adaption of some health policies, such as lockdowns and isolation for preventing disease transmission, has led to restricting the mobility, social interactions, and daily activities of people [3]. Despite the positive consequences of implementing health policies during the outbreak of COVID-19, these policies have also had negative effects at the community level [9]. For this reason, the recent epidemic has encouraged countries worldwide to consider supportive policies to protect their societies, including supporting employment, providing unemployment benefits, and creating social programs for vulnerable working groups. To comply with social distancing, insurance organizations utilize a variety of service delivery models (e.g., more use of digital channels, call centers to provide services to people, etc.). Universities and educational institutions have also had to change their educational systems, so in some countries, the education system has even changed to virtual space [10].

Although the outbreak of COVID-19 has impacted every country in the world, some countries have implemented accurate and timely policies that have caused minimal damage. For instance, what has been observed in China and its policies in support of disease prevention and control have been relatively successful in controlling the disease by adopting isolation and lockdown policies despite the influx of people [11].

In some countries, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching impacts. In the area of employment in Iran, macro surveys show that some individuals have not only lost their jobs due to COVID-19, but in addition to not having insurance, they had no access to government facilities and financial assistance. Although the government's support for managing labor supply and demand markets and support programs has been somewhat effective in this field [12]. Thus, given what has been mentioned, an important point for governments to consider when implementing health policies is to focus on the dimensions and problems caused by emerging diseases such as COVID-19. Social support and help to resolve the damage caused by COVID-19 should be placed in the work priorities of governments.

Therefore, the fundamental issues that arise in those areas for society members are how much people know about the support provided by the government and national and provincial policymakers and how much such support is tangible and could be implemented. Since no such research has been done in this field in Iran, it seems necessary to know the views of people from different professions regarding the perceived support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the perceived social support of Hamadan citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants and Methods

This content analysis qualitative study was conducted from September to December 2022 in the Hamadan province; 42 in-depth semi-structured interviews were completed with men and women residents. Eligible participants were adults over 18 and heads of household. They were physically and mentally capable of participating in this study and gave informed consent.

Participants were selected from different occupational groups. They were informed about the study objectives and procedures, and a consent form was signed if they agreed to participate. Once eligibility was established, an appointment was made for interviews. Before the start of each interview, the intended usage of an audiotape machine to record the interviews was explained to the study participants. We asked about demographic information, including age, marital situation, employment status, and level of education (warm-up questions). Interviews explored social support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interviews explored individuals' perceptions of social and occupational support during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research question guiding this exploration was:

1. What problems did you have in getting the right information about the disease during COVID-19?

2. What problems did you have in getting the right information in your job development?

3. What new crises did you encounter during the COVID-19 pandemic?

4. What psychological and emotional wounds did you have during the COVID-19 disease?

5. What financial losses did you have during the COVID-19 pandemic?

6. How did you manage your financial needs?

7. How did you evaluate your life conditions?

8. How did your family and others evaluate your job situation?

All interviews were conducted in a private room by two of the researchers. Each face-to-face interview lasted approximately 30 minutes. Interviewers were familiar with the local language, and all interviews were conducted in the local languages predominantly spoken in the study area. The researchers had previous training and experience in qualitative interview techniques and qualitative research procedures. We confirmed that all data would remain confidential and they could stop the interview or skip questions they did not like answering. One researcher asked questions, while the research assistant managed the audio equipment and took notes during the interview. Interview and sampling were continued until saturation was achieved. Also, researchers increased the credibility of the data by establishing a close rapport with participants and double-checking the notes and recorded transcripts.

The research team transcribed all interviews verbatim and double-checked the transcripts for accuracy. The team chose a qualitative content analysis approach to identify and investigate occupational and social support [13]. We conducted this approach in three steps preparation (researchers tried to make sense of the data. The goal was to immerse in the data, which is why the writings were read several times), organizing (process of open coding and creating categories, grouping codes, and, formulating an overall description of the research issues via making abstract categories and subcategories), and, reporting (interpretation, to which texts are to be placed under similar categories and subcategories). These techniques were employed, and the results of the coding process were documented to help construct a coherent category system.

Findings

The sample included 62.8% males and 37.2% females. The mean age of the participants was 39.85±9.57 (24 to 65 years). The mean of the participants’ households was 3.38±1.28 (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of the participants

Social support is the functional content of relationships which can be categorized into four types of supportive behavior or action:

Emotional

Emotional support provides affection, kindness, and attention to another person and ensures the person feels valued and noticed. In this regard, the participants’ claims showed that they received the highest support from their families.

Participant No. 5 (male, hairdresser, 32 years) stated:

“I have a very close relationship with customers because of my job, which was dangerous during the COVID-19 times. Nevertheless, my wife was kind to me like before. She was not worried if I spread the disease in the house”.

Participant No. 32 (male, worker, 35 years) claimed:

“Although my job status experienced recession and seasonal jobs were low and also, I am a tenant and do not have much income, my wife and my parents always told me: Everything will be alright. Also, they expected me to spend less money”.

However, the participants sometimes talked about the lack of attention from family and relatives.

Participant No. 4 (male, shop owner, 28 years) stated:

“We were among the businesses that had to close the shop during the COVID-19 times. That was why we stayed home. Sometimes, I had arguments with my wife as if we were used to seeing each other only at night”.

Participant No. 15 (female, hairdresser, 34 years) said:

“Honestly, I complained to my husband why he came home late but during the COVID-19 times that we both had to stay home, we felt that we were fed up with each other, so we had quarrels with each other under different excuses. I can say that we were all anxious.”

Informational

Information support provides consultation, suggestions, and information that a person can use to solve problems. This kind of support occurs when a person helps another person understand a stressful situation better and determines which source and coping strategy are required to face that situation. Most participants sought appropriate information during the COVID-19 crisis and acquired information from official and unofficial channels.

Participant No. 17 (male, baker, 31 years) stated:

“We were one of the businesses that should not have been closed, and just God knows what difficulties we went through. Every day, we hear different information. We did not know whether to believe the TV news or social media”.

Another participant (male, bank clerk, 39 years) stated:

“We were in danger because of our customers and the closed atmosphere of the bank. I got infected with COVID-19. Sometimes, the information was scary but nowhere could be reliable except the health centers and hospitals. They worked as much as they could and provided us with the right information as well”.

A housewife stated:

“I would sit in front of the TV all day to see what we had to do. I tried to comply with all the orders they gave. But sometimes I heard things from friends and neighbors and could not distinguish who told the truth”.

Instrumental

Instrumental support provides tangible aids such as services, financial aid, and other specific goods. This type of support includes aid for the shortage of financial resources such as money and accommodation or may solve daily life problems such as child care, housework, etc. Regarding the COVID-19 crisis, most participants had encountered financial problems, according to their statements. Instrumental support was categorized into two areas of support from family, friends, guilds, and government.

Participant No. 32 (male, driver, 45 years) expressed:

"I pay installments for my car. If I do not work, I can pay the installments aside from the extra costs of the car like tires or gas. There were fewer passengers because of the limitations and our income had reduced. The :union: did not help at all and I did not know what to do with my installments”.

Participant No. 39 (housewife, 52 years) said:

"My husband had rented a fast-food stand with his friend. We are also a tenant. When our shop was closed during the lockdown times, our conditions got worse as well. We had heard that the tenants and loan receivers would be given a grace time during the COVID-19 era, but it was not true and we lived with difficulty”.

Another participant (female, housewife, 24 years) stated:

“At the beginning of the COVID-19 days, they said hospitals and health centers supplied masks and disinfectants. We referred to those places several times but they said that was not true. Masks and disinfectants were expensive and rare”.

Meanwhile, a 26-year-old female teacher stated the problem in another way:

“It is true that I was a government employee and had a fixed annual salary, but COVID-19 turned classes online. It was not possible to supply a phone or tablet for my child. I had even students who could not buy a phone and it was difficult to teach them. Phone or tablet was not the only problem. Internet problems and the lack of a good program were other problems which that all families were coping with. Support was presented in a different way in terms of support from family and relatives”.

Participant No. 3 (male, jewelry seller, 36 years) claimed:

"The market works with checks and securities. People referred to the market less and bought less. I had checks as well. I asked everyone I knew to help me but they did not even those to whom I had lent money before when they had problems”.

However, another participant (male, mechanic, 53 years) stated:

"We had also financial problems like all other businesses. We had to use our savings. When the savings were over, my father and brothers helped me".

Appraisal

Appraisal support provides useful information for self-evaluation. In other words, feedback from others on performance can result in improvement. The participants in the present study reported various appraisal supports.

Participant No. 18 (30 years, marketer) said:

“We had to communicate with production and sales units because of our job conditions. We referred to electronic advertising and services when some businesses were down due to COVID-19. Actually, the customers were satisfied and we developed our services. At least, we could reduce many transportation costs".

Another participant (male, computer services, 24 years) stated:

"COVID-19 greatly helped the computer service businesses. Although the businesses were closed, we could provide services out of the office. Most organizations and companies required offline services and that was in our favor. Our customers were also satisfied and it gave a good feeling, I mean both customer satisfaction and more profits”.

On the other hand, some businesses did not receive good feedback during the COVID-19 period.

Participant No. 15 (male, teacher, 45 years) explained:

"Online education was not what we thought. The problems related to phones, tablets, and the internet on the one hand and the major problems of dissatisfaction with education on the other hand. The inadequate and unfavorable activity of students meant the poor performance of the teacher. We did not have any good feedback as we tried and this is an alarm”.

Another employee said:

"They changed the working hours during the COVID-19 times and some personnel worked either part-time or remotely. This process was not very appropriate. The customers were the same but we faced problems with our tasks. The customers were not satisfied at all. I had to do my colleague's duties as well during the working day and I was not very successful at all, or on the day when my colleague worked instead of me, he did not do the job as he had to”.

Discussion

The present study's findings showed that the social support perceived by our study participants during the COVID-19 pandemic was classified into four categories: Informational support, emotional support, instrumental support, and appraisal support.

The evidence indicates that people benefiting from various types of social support are in better health conditions than people without social support, and as these supports increase, mental health also increases, and the incidence of clinical disorders decreases [14].

The participants of our study stated that due to facing a newly emerging disease and the stressful situation of this disease, they tried to obtain information from various official and unofficial channels to learn more about the disease and its details. In the early stages of a crisis, the informational support of the public population is vital [15]. Informational support included reference/referral, advice, feedback/opinion, facts, personal experience, and perceptual knowledge [16, 17]. The results of a study in Iran revealed that many of the participants stated the use of social networks in information and education to increase public awareness in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic to be very effective and believed that social networks could be a suitable platform for information, education, and awareness [18] and a study in Taiwan showed that the most used sources of information related to COVID-19 in the studied subjects were the internet, traditional media, and family members respectively [19]. In Iran, official internet news agencies, traditional media, doctors, and healthcare personnel were the most important sources of information about COVID-19 [20]. Regarding information support, it is important that correct and reliable information is available to the public. Although the spread of the pandemic and the information related to COVID-19 spread on different media platforms, the infodemic was a big challenge in the recent pandemic [21]. In the present study, the participants stated that in addition to the need to obtain information, they also needed reliable information support; Because sometimes contradictory information was published in mass media and virtual space, which confused the people. As the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak, the world was quickly confronted with an overwhelming amount of true and false information that made it difficult to find reliable information for the people who needed it, what is termed by the World Health Organization as infodemics [22, 23]. The main information challenges this society faced during COVID-19 included the lack of a scientific reference source to access accurate information and the existence of a large amount of information in virtual networks, which led to confusion among people in society [21]. The main reason for the infodemic is the increase in people's access to the internet and social media, which in a short time gives a person a huge amount of information, which may be only a part of this reliable information [22]. Infodemics can have very bad effects on pandemics, such as making it difficult to access reliable sources and documents for the general population and health policymakers, increasing negative psychological consequences, including creating feelings of anxiety and depression in the general population, and delays in quick decisions and the inability of officials to control the published content [23]. During pandemics, policymakers must carefully consider the quality of information disseminated through different sources. In addition, when disseminating urgent health information, various and reliable sources should be used to ensure that different populations have access to critical knowledge [24].

Also, our participants stated that the healthcare system supported the citizens more than other sources of information, so this source was more reliable for the citizens. A national study in Japan showed that although television was the most used source of information, doctors and nurses were the most reliable sources of information [25].

Evidence shows that emotional support during a crisis can be very helpful in relieving general emotions [15]. The results of our study showed that most of the participants had received emotional support from their families during the pandemic. Family support is very important in times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The family can provide peace and control the emotions of family members (both sick and healthy members) by creating a safe place [26]. The participants of the study stated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, they had anxiety and worry due to contracting the disease and transmitting it to family members. Available evidence proves that isolation from family, relatives, and friends, deprivation of psychological support during hospitalization, worry about other family members getting sick, and social stigma caused by getting sick significantly increase anxiety in patients [27, 28]. Another study disclosed that due to the high prevalence of anxiety and depression in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, more family support for sick people prevents the transformation of these symptoms into long-term mental disorders [29]. The types of social support of the family for the affected people lead to the recovery of those affected by COVID-19. However, the strongest component related to the recovery of the patients was the family's emotional support [26]. The results of a multinational cross-sectional survey have confirmed that the lack of emotional support is mentioned as an independent risk factor for developing psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression during the recent pandemic [30]. Some of the citizens of our study also reported that they had not received any emotional support from their family and friends. These people believed that during COVID-19, staying at home caused frequent family arguments and bothered the family members. Considering the nature of the spread of the disease, one of the disease control policies was home quarantine, which caused family members to spend more time together at home during the outbreak of COVID-19. In this era, fear of illness, fear of death, the spread of false news and rumors, interference in daily activities, prohibitions or restrictions on travel and transit, reduction of social relations, and the occurrence of job and financial problems were threatening the mental health of families [31]. So, when families experience stress caused by negative life events, their adaption decreases [32]. This can cause dysfunctional responses in family members, leading to the formation and intensification of family conflicts [33]. Of course, we should not neglect the effect of the heavy use of social networks in this era. On the one hand, increasing the time spent using social networks during lockdown negatively affects couples' relationships and feelings towards each other and strengthens self-infatuation; on the other hand, it leads to various communication problems, reducing positive feelings of couples and marital conflicts [34]. The evidence shows that in epidemics, a healthy relationship, effective communication, positive thinking, and emotional support can create a more adaptive response to the crisis [35].

Most of the participants reported that they faced financial problems during the COVID-19 crisis. These problems included postponement of house and shop rents, inability to repay loans, bounced bank checks, reduced monthly income due to frequent holidays, use of savings for daily living, increasing in household health expenses, such as the costs of buying masks and disinfectants, the need to purchase smartphones/tablets and internet to participate in virtual classes.

A study in Chile confirmed that during the pandemic, unemployment and loss of income predicted the experience of many financial problems, such as reduced savings, problems in paying bills, debt, and mortgage loans [36]. The participants of the present study also stated that although they were sometimes financially supported by their families, despite the financial problems, they were not given any financial support by the :union:. In other words, considering the existing financial problems, the study participants expected the :union:s to adopt supportive policies in this field. Han's study in the USA indicated that :union: workers had more job security than non-:union: workers and received more pay for the hours they did not work due to COVID-19 [37]. Evidence proves that financial problems during the pandemic caused psychological problems in different populations, especially vulnerable populations [36, 38]. One of the coping strategies for managing psychological problems related to financial problems during the pandemic is to facilitate social support, improving public health facilities and improving health insurance, financial support for pregnant women and child care, special care for the elderly, and adopting policies to revive damaged businesses and strengthen entrepreneurs [38].

In the field of appraisal support, the study participants stated that they had received different feedback from others regarding their performance. For example, the participants with jobs that could provide services electronically expressed a tendency towards electronic services and advertising. Its expansion caused more profit and increased customer satisfaction.

Lockdown and the need for social distancing as policies adopted during the pandemic caused significant changes in online shopping, introducing digital payment systems, remote work, and electronic service delivery [39]. Evidence shows that the quality of electronic services is the key to achieving customer satisfaction [40]. It seems that in different communities, with the spread of COVID-19, the provision of electronic services has been developed, leading to customer satisfaction.

Some participants also believed that during COVID-19, education in the virtual space caused dissatisfaction among both students and teachers with the teaching method. In the era of COVID-19, one of the important changes in the education field worldwide was virtual education instead of face-to-face education [41]. This sudden change brought many challenges for people involved in education [42]. Teachers faced challenges implementing online education due to insufficient training with digital tools, lack of constant contact with students to monitor their study routine, and lack of support and help from parents [43]. A national study of medical students showed that despite the high flexibility of online education platforms, family distractions and poor internet connection were major problems with using these platforms [44]. The result of a study in Iran regarding the problems of online education also reported that the problems of virtual education from the teachers' point of view include the harm of excessive use of the internet by students, the problems of the special network for students, and digital resources, the violation of educational justice, the lack of basic facilities, the problems of the teaching-learning process, job pressure, parents' non-cooperation and low media literacy and from the parents' view included lack of basic facilities, damages of excessive use of the internet, reduction of teacher's efficiency, interruption in student's personality development, reduction of motivation, disruption of home order and unfamiliarity with the elements and educational skills of parents [45]. On the one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic increased the beneficiaries' skills and educational experience. On the other hand, it caused physical and mental disorders, academic failure, and job burnout [46]. Considering the challenges of virtual education, it seems that this issue will be developed in the future with the design of coherent and effective infrastructures, fundamental revision of human, financial, and support resources and lead to productivity.

In this study, telecommuting of employees in different departments caused disruptions in the performance of their work duties and reduced client satisfaction. With the spread of COVID-19, various organizations had to quickly train their employees to perform their work duties online and at home while maintaining productivity. Many employees faced difficulties adapting to online work, combining work hours with daily tasks, family commitments, information security, and privacy [47]. The benefits of telecommuting working in Indonesian teachers include more flexibility, no tracking of work hours, no travel expenses, reduced stress levels, and more free time. However, reduced work motivation was reported as a disadvantage [48]. Russian employees have perceived remote work as a positive experience [49]. Remote work can be a short-term and long-term answer to urban issues and emergency conditions. However, remote work has not yet become mainstream in modern human life [50].

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic has shed light on global crises' irrefutable mental and social health repercussions. Crucially, this pandemic highlighted the detrimental impact on households' jobs and incomes.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful to all those who participated in the study.

Ethical Permissions: The Ethical Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (IR.UMSHA.REC.1401.211).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contributions: Ezzati Rastegar K (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (30%); Khoshravesh S (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (15%); Behzad G (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (10%); Khazaei S (Fourth Author), Introduction Writer (5%); Soltanian AR (Fifth Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (40%)

Funding/Support: The authors thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for support (No. 140103171646).

Keywords:

References

1. Javaid M, Khan IH, Vaishya R, Singh RP, Vaish A. Data analytics applications for COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Med Res Pract. 2021;11(2):105-6. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/cmrp.cmrp_82_20]

2. Labrague LJ. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(7):1893-905. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13336]

3. Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42:e2020038. [Link] [DOI:10.4178/epih.e2020038]

4. Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, Faizah F, Mazumder H, Zou L, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636. [Link] [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.24457.1]

5. Li X, Wu H, Meng F, Li L, Wang Y, Zhou M. Relations of COVID-19-related stressors and social support with Chinese college students' psychological response during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fron Psychiatry. 2020;11:551315. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.551315]

6. Roberts JE, Gotlib IH. Social support and personality in depression: Implications from quantitative genetics. In: Pierce GR, Lakey B, Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Sourcebook of social support and personality. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. p. 187-214. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4899-1843-7_9]

7. Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer J. Handbook of health psychology. 2nd ed. New York: Psychology Press; 2011. [Link] [DOI:10.4324/9780203804100]

8. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. Hoboken: Jossey-bass Publishing; 2008. [Link]

9. Narimani M, Eyni S. The causal model of coronavirus anxiety in the elderly based on perceived stress and sense of cohesion: The mediating role of perceived social support. Aging Psychol. 2021;7(1):13-27. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.1177/23337214211048324]

10. Mirhaji SS, Soleymanpour M, Saboury AA, Bazargan A. A look at the Corona virus and the evolution of university education in the world: Challenges and perspectives. Environ Hazards Manag. 2020;7(2):197-223. [Persian] [Link]

11. Doshmangir L, Mahbub Ahari A, Qolipour K, Azami-Aghdash S, Kalankesh L, Doshmangir P, et al. East Asia's strategies for effective response to COVID-19: Lessons learned for Iran. Manag Strateg Health Sys. 2020;4(4):370-3. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.18502/mshsj.v4i4.2542]

12. Taherinia M, Hassanvand A. Economic consequences of Covid-19 disease on the Iranian economy; With an emphasis on employment. Q J Nurs Manag. 2020;9(3):43-58. [Persian] [Link]

13. Moeini B, Rezapur-Shahkolai F, Jahanfar S, Naghdi A, Karami M, Ezzati-Rastegar K. Utilizing the PEN-3 model to identify socio-cultural factors affecting intimate partner violence against pregnant women in Suburban Hamadan. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(11):1212-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/07399332.2019.1578777]

14. Mishra S. Social networks, social capital, social support and academic success in higher education: A systematic review focusing on 'underrepresented' students. Educ Res Rev. 2020;29:100307. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100307]

15. Zhu R, Hu X. The public needs more: The informational and emotional support of public communication amidst the Covid-19 in China. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023;84:103469. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103469]

16. Chuang KY, Yang CC. Informational support exchanges using different computer‐mediated communication formats in a social media alcoholism community. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2014;65(1):37-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/asi.22960]

17. Cutrona CE, Suhr JA. Controllability of stressful events and satisfaction with spouse support behaviors. Commun Res. 1992;19(2):154-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/009365092019002002]

18. Janavi E, Mardnai F. The effect of information and education through social networks on the level of public awareness during the COVID-19 pandemic (case study: Tehran). Sci Tech Inf Manag. 2022;8(1):45-72. [Persian] [Link]

19. Wang PW, Lu WH, Ko NY, Chen YL, Li DJ, Chang YP, et al. COVID-19-related information sources and the relationship with confidence in people coping with COVID-19: Facebook survey study in Taiwan. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e20021. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/20021]

20. Yasamani K, Khalkhali HR, Farrokh Eslamlou HR, Didarloo A. Determinants of COVID-19 preventive behaviors among women of reproductive age in Urmia using a behavioral change model in 2021. Health Educ Health Promot. 2022;10(4):665-72. [Link]

21. Atighechian G, Rezaei F, Tavakoli N, Abarghoian M. Information challenges of COVID-19: A qualitative research. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:279. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1271_20]

22. PAHO. Understanding the infodemic and misinformation in the fight against COVID-19. Washington, D.C: Pan American Health Organization; 2020. [Link]

23. Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X]

24. Fridman I, Lucas N, Henke D, Zigler CK. Association between public knowledge about COVID-19, trust in information sources, and adherence to social distancing: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(3):e22060. [Link] [DOI:10.2196/22060]

25. Uchibori M, Ghaznavi C, Murakami M, Eguchi A, Kunishima H, Kaneko S, et al. Preventive behaviors and information sources during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14511. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph192114511]

26. Wardani DS, Arifin S. The role of family support in the recovery of corona virus disease-19 patients. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2021;9(E):1005-9. [Link] [DOI:10.3889/oamjms.2021.6025]

27. Carvalho PMM, Moreira MM, De Oliveira MNA, Landim JMM, Neto MLR. The psychiatric impact of the novel coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;286:112902. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112902]

28. Zhou X, Snoswell CL, Harding LE, Bambling M, Edirippulige S, Bai X, et al. The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(4):377-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/tmj.2020.0068]

29. Largani MH, Gorgani F, Abbaszadeh M, Arbabi M, Reyhan SK, Allameh SF, et al. Depression, anxiety, perceived stress and family support in COVID-19 patients. Iran J Psychiatry. 2022;17(3):257-64. [Link]

30. Jagiasi BG, Chanchalani G, Nasa P, Tekwani S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the emotional well-being of healthcare workers: A multinational cross-sectional survey. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25(5):499-506. [Link] [DOI:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23806]

31. Valero-Moreno S, Lacomba-Trejo L, Casaña-Granell S, Prado-Gascó VJ, Montoya-Castilla I, Pérez-Marín M. Psychometric properties of the questionnaire on threat perception of chronic illnesses in pediatric patients. Revista Latino Americana de Enfermagem. 2020;28:e3242. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/1518-8345.3144.3242]

32. Lavi I, Fladeboe K, King K, Kawamura J, Friedman D, Compas B, et al. Stress and marital adjustment in families of children with cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(4):1244-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pon.4661]

33. Timmons AC, Arbel R, Margolin G. Daily patterns of stress and conflict in couples: Associations with marital aggression and family-of-origin aggression. J Fam Psychol. 2017;31(1):93-104. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/fam0000227]

34. Rezapour R, Zakeri MM, Ebrahimi L. Prediction of Narcissism, perception of social interactions and marital conflicts based on the use of social networks. J Fam Res. 2017;13(2):197-214. [Persian] [Link]

35. Gayatri M, Irawaty DK. Family resilience during COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Fam J Alex Va. 2022;30(2):132-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/10664807211023875]

36. Borrescio-Higa F, Droller F, Valenzuela P. Financial distress and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Public Health. 2022;67:1604591. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/ijph.2022.1604591]

37. Han ES. What did :union:s do for :union: workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic?. Br J Ind Relat. 2023;61(3):623-52. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bjir.12716]

38. Singh S, Bedi D. Financial disruption and psychological underpinning during COVID-19: A review and research agenda. Front Psychol. 2022;13:878706. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.878706]

39. Renu N. Technological advancement in the era of COVID-19. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/20503121211000912]

40. Khan SA, Epoc F, Gangwar V, Ligori TAA, Ansari ZA. Will online banking sustain in Bhutan post COVID-19? A quantitative analysis of the customer e-satisfaction and e-loyalty in the kingdom of Bhutan. Transnatl Mark J. 2021;9(3):607-24. [Link] [DOI:10.33182/tmj.v9i3.1288]

41. Aboagye E, Yawson JA, Appiah KN. COVID-19 and e-learning: The challenges of students in tertiary institutions. Soc Educ Res. 2020;2(1):1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.37256/ser.212021422]

42. Zheng M, Bender D, Lyon C. Online learning during COVID-19 produced equivalent or better student course performance as compared with pre-pandemic: Empirical evidence from a school-wide comparative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):495. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12909-021-02909-z]

43. Shamir-Inbal T, Blau I. Facilitating emergency remote K-12 teaching in computing-enhanced virtual learning environments during COVID-19 pandemic-blessing or curse?. J Educ Comput Res. 2021;59(7):1243-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0735633121992781]

44. Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al-Nusair L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042378. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378]

45. Yadollāhi S, Tavakoli Torghe E, Poorsālehi Navide M, Āzartāsh F. Online teaching problems during COVID 19 pandemic from teachers and parents' viewpoints and suggesting practical solutions. J Educ Innov. 2021;20(3):117-45. [Persian] [Link]

46. Hajizadeh A, Azizi G, Keyhan G. Analyzing the opportunities and challenges of e-learning in the Corona era: An approach to the development of e-learning in the post-Corona. Res Teach. 2021;9(1):174-204. [Persian] [Link]

47. Al-Habaibeh A, Watkins M, Waried K, Javareshk MB. Challenges and opportunities of remotely working from home during Covid-19 pandemic. Glob Transit. 2021;3:99-108. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.glt.2021.11.001]

48. Purwanto A, Asbari M, Fahlevi M, Mufid A, Agistiawati E, Cahyono Y, et al. Impact of work from home (WFH) on Indonesian teachers performance during the Covid-19 pandemic: An exploratory study. Int J Adv Sci Technol. 2020;29(5):6235-44. [Link]

49. Toscano F, Bigliardi E, Polevaya MV, Kamneva EV, Zappalà S. Working remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic: Work-related psychosocial factors, work satisfaction, and job performance among Russian employees. Psychol Russ. 2022;15(1):3-19. [Link] [DOI:10.11621/pir.2022.0101]

50. Mendrika V, Darmawan D, Anjanarko TS, Jahroni J, Shaleh M, Handayani B. The effectiveness of the work from home (WFH) program during the Covid-19 pandemic. J Soc Sci Stud. 2021;1(2):44-6. [Link] [DOI:10.56348/jos3.v1i2.12]