Volume 16, Issue 2 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(2): 143-150 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/12/5 | Accepted: 2024/06/27 | Published: 2024/07/10

Received: 2023/12/5 | Accepted: 2024/06/27 | Published: 2024/07/10

How to cite this article

Hrefish Z, Hussein M. Psychological Burdens Experienced by Wives of Disabled People; A Focus on Disability-Related Factors. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (2) :143-150

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1413-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1413-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Psychological Burdens Experienced by Wives of Disabled People; A Focus on Disability-Related Factors

Authors

Z.A. Hrefish *1, M.A. Hussein2

1- Department of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Babylon, Hilla, Iraq

2- Department of Family and Ccommunity Health Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Babylon, Hilla, Iraq

2- Department of Family and Ccommunity Health Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Babylon, Hilla, Iraq

Full-Text (HTML) (924 Views)

Introduction

It is estimated that over a billion people around the globe live with some type of disability. The primary causes of these disabilities are often linked to chronic health conditions, such as visual impairment resulting from diabetes. Spouses of individuals with disabilities experience severe and complex psychological difficulties that vary depending on a set of parameters associated with the disability. Emotional exhaustion, anxiety, depression, and social isolation are common manifestations of these stressors [1]. The physical demands and chronic nature of the disability exacerbate the emotional burden of caregiving, which women typically bear. This caregiving dynamic often leads to feelings of being trapped and losing independence, as caring for a disabled spouse can involve many difficult and stressful tasks [2].

These mental costs result from several disability-related problems. The type of condition and its severity are important factors to consider. For example, disabilities, such as severe motor impairment or cognitive disorders that require regular monitoring or significant physical care place a greater burden on caregivers [3]. Long-term or permanent disabilities cause constant stress and progressively reduce the caregiver’s flexibility, making the duration of the condition a crucial issue. Wives often face financial struggles and social rejection, which can lead to feelings of helplessness and despair. These factors, along with the social stigma and economic obstacles associated with disability, further exacerbate psychological burdens [4].

Moreover, a woman’s psychological effects may be greatly influenced by her marital status before the onset of the disability. A strong and stable marriage can act as a stress reliever and reduce some of the emotional strain [5]. On the other hand, the caregiver’s perception of loneliness and psychological pain may be exacerbated by pre-existing marital discord or a lack of emotional closeness [6]. Spouses of individuals with disabilities often find significant relief from their limitations through their social support networks, underscoring the need for comprehensive support systems to address these psychological burdens. Such networks include friends, extended family, and community services [7].

Disability as an interpersonal experience affects the people patients are close with. Close relationship partners show the same levels of psychological distress as patients. For example, meta-analytic data suggest comparable patient and spouse psychological distress, which means that distress does not significantly differ between them. Although other family members also suffer, romantic partners are more at risk of developing distress related to the patient's impairment. Spouses of individuals with disabilities face significant psychological challenges that are influenced by a complex web of interconnected elements related to both the disability and the larger social and relational environment. A comprehensive strategy is needed to address these challenges, including social services, psychological support, and policies designed to reduce caregiving stress and improve the quality of life for individuals with disabilities and their spouses [1, 8]. We need to recognize the genuine needs of individuals with disabilities, as well as those of the caregivers who share their lives. Among these caregivers is the wife, who experiences similar challenges and circumstances as any other wife; however, the burdens faced by wives of individuals with disabilities are more intricate and significant, encompassing various economic, psychological, and social pressures. Due to their husband’s disability, many women are compelled to take on a productive role in addition to their responsibilities in managing the household and educating their children [9]. Furthermore, the psychological burdens imposed by society, stemming from a limited perception of the disabled individual and their family within a traditional cultural framework, complicate and hinder the adjustment process [10]. Caring for a sick or disabled family member can have negative emotional, social, and financial effects on the caregiver. In Iraq, strong family bonds and the importance of traditions are prevalent, leading family members to share both happiness and hardship. This unique aspect of Iraqi culture means that care for individuals with disabilities is a lifelong commitment. Typically, the primary caregivers are first-degree relatives, often wives, who not only help with the care of the disabled but also provide emotional support. While this role can bring emotional fulfillment to the caregiver, challenging living conditions can lead to various difficulties [11].

Several factors influence the burdens experienced by wives of individuals with disabilities. The challenges faced by illiterate wives differ from those of wives who are primary, secondary, or college graduates; specifically, lower educational attainment correlates with greater burdens. This relationship is largely attributed to economic circumstances, as many individuals without formal education lack employment and encounter financial difficulties. Consequently, there is little difference in burdens between those with low and moderate incomes, while those with higher incomes tend to experience fewer burdens than those with limited financial resources. The findings of this study align with existing literature, which indicates that higher education levels are associated with reduced caregiver burdens. For instance, Papastavrou et al. found that primary school graduates faced a significantly higher caregiver burden [12]. Stenberg et al. noted that caregivers with a bachelor’s degree reported a disproportionately low financial burden compared to others [13], and Shieh et al. indicated that higher education levels predicted a significantly lower caregiver burden [14]. Furthermore, Park et al. demonstrated that individuals with higher education levels received much greater family support [15]. A study in Mazandaran showed that there are many psychological problems in the spouses of neuropsychiatric veterans and the spouses of chemical veterans of the Iran-Iraq war; however, the results showed no significant change in the two groups based on age, number of children, percentage of injury, and literacy level [16].

As the number of individuals living with disabilities increases, a greater number of relationship dynamics will be affected by the implications of disability. Women encounter numerous challenges and issues stemming from gender distinctions rooted in traditional culture, and these challenges are particularly pronounced for the wives of individuals with disabilities. Assisting the wives of the disabled in adapting and alleviating these burdens, difficulties, and gaps in support is a crucial priority for easing their struggles and facilitating their integration into society. Therefore, this study assessed the psychological burden among wives of individuals with disabilities in light of disability-related factors at the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability in Iraq.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sample

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability from April 2 to June 12, 2024. A sample of 250 wives of individuals with disabilities in Babylon Province was used for the study; this sample constituted about 10% of the total study population. From the list of spouses registered with the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability, simple random sampling was employed to select the sample. According to the monthly reviews, there were 992 views in total and a quarter of the study community was appropriately selected.

Research tools

A checklist collected socio-demographic factors, including the age of the spouses, level of education, and monthly income. Factors associated with disability included the types of disabilities, the causes of disabilities, and the duration of disabilities. The 22 items of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (ZCBS), developed by Zarit et al. in 1980 [17], measured how caregiving affects the caregiver. Each item is rated as never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), very often (3), and usually almost always (4) on a five-point Likert scale. The maximum score on the scale is 88, while the lowest possible score is 0. A high score indicates an increased burden on spouses. The validity and reliability of the scale were examined in Iraq by Malih Radhi et al., with results showing that the test-retest reliability was 0.81 and that the internal consistency ranged from 0.87 [1].

The reliability of the research tool was evaluated by conducting a pilot study that included 20 respondents, or 10% of the study sample. When the participants visited the Babylon Center for Rehabilitation of the Disabled, the researcher provided a brief introduction and asked them to complete a questionnaire to share their thoughts and participate in the study. Next, the researcher presented a summary of the study objectives and title to assess the clarity of the study and the ease of understanding of the questionnaire. It was expected that each form would take about 20 minutes to complete. After examining the data, the responses from the pilot study were excluded from the sample without making any changes. In our research, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.81, indicating a reasonable degree of reliability.

Data collection

The data were collected over a full month at the Babylon Center for Rehabilitation of the Disabled. The researchers conducted individual interviews with each study participant to explain the project’s goal and obtain verbal consent. Participant interviews were used to collect data according to the inclusion criteria.

Participants studying psychological difficulties among couples with disabilities must meet several requirements to be considered for inclusion. The first requirement is that they must be adult females (18 years and older) currently married to someone with a recognized disability, such as a physical, intellectual, or sensory disability. To ensure that the impairment has a significant impact on daily functioning, it must be medically verified and have persisted for at least six months. Furthermore, participants must live with their spouses with disabilities to ensure the sharing of daily experiences and caregiving obligations. In addition to being willing to participate in surveys or interviews about their psychological and emotional experiences, they must also be able to provide informed consent. Participants must have been providing care for at least six months to demonstrate that they have significant experience managing the psychological responsibilities that come with the role.

Those who did not meet the age or gender requirements were not allowed to participate in the study, following the exclusion criteria. Spouses of individuals with short-term disabilities (less than six months) were not eligible, as the study focused more on the long-term psychological effects. Furthermore, individuals who were not living with a spouse with a disability were not accepted, as their caregiving experiences may differ significantly from those of individuals who live with their spouses. To further ensure the validity of the data, women with serious mental health issues or cognitive impairments that prevent them from providing informed consent or accurately recalling their experiences were excluded. Finally, to avoid biases or confounding effects in the data collected, participants involved in other psychological research on caregiving were not permitted to participate.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20 software. Numbers and percentages were used to rank parameters, while the mean and standard deviation were used to statistically describe continuous parameters. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were employed to test for normality. In addition, associations and predictors among study parameters were examined using simple linear regression and the Kruskal-Wallis test. A significance threshold of 0.05 was applied to the statistical interpretations.

Findings

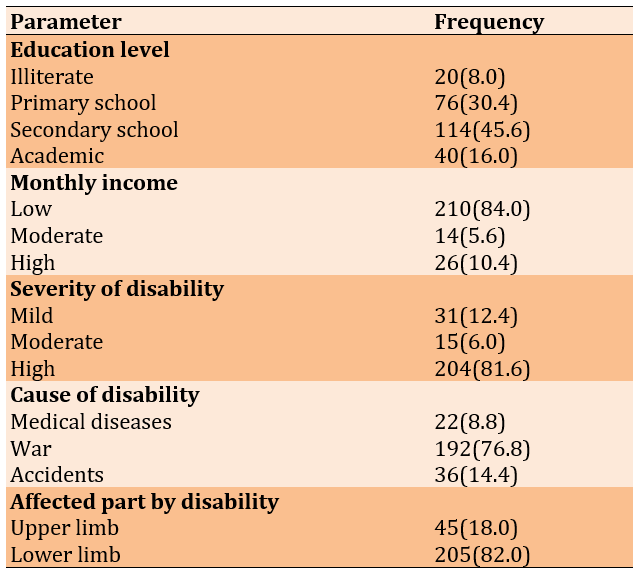

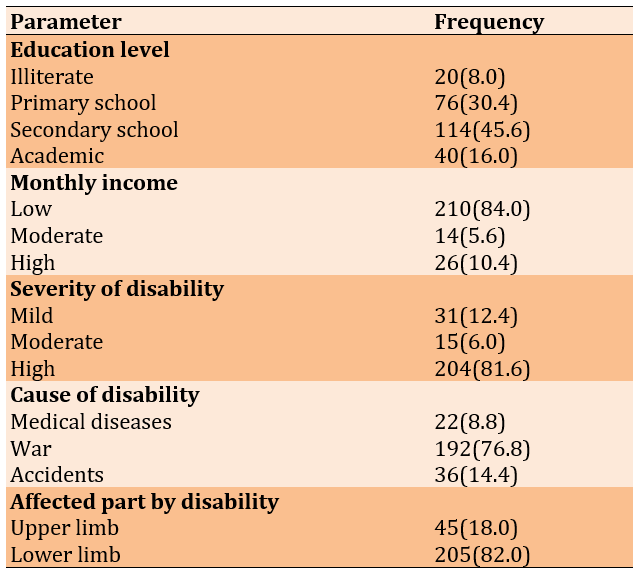

The mean age of participants was 37.93±10.02 years. Notably, most samples were secondary school graduates (45.6%). The majority of the study sample reported a low monthly income (84.0%). Additionally, 81.6% expressed a high severity of disability. War was identified as the major cause of disabilities (76.8%), with lower limb disabilities accounting for 82.0%. The average duration of disabilities was 9.87±5.09 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and disability-related factors

A significant proportion (204, 81.6%) of the wives of people with disabilities reported a high psychological burden, followed by those indicating moderate (26, 10.4%) and low (20, 8.0%) levels. The total mean score of psychological burdens was 73.87±19.44.

The linear regression analysis indicated the predicted relationship between psychological burdens among wives of people with disabilities and their monthly income, severity of disabilities, and duration of disabilities (Table 2).

Table 2. Linear regression analysis of the study parameters to predict psychological burdens

Every decrease in monthly income was associated with an increase in psychological burdens among the wives of disabled individuals by 29.28 times. When the disability became severe, there was an increase in psychological burdens among the wives of disabled individuals by 27.83 times. Also, every increase in the duration of disability was associated with an increase in psychological burdens among the wives of disabled individuals by 2.340 times.

The findings of the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in psychological burdens among wives of people with disabilities based on the reasons for their husbands’ disabilities (p=0.001) and the affected parts due to disabilities, whether upper or lower limbs (p=0.001; Table 3).

Table 3. Differences in psychological burdens based on the cause of disability and affected parts due to disability

Discussion

This study assessed the psychological burden among wives of individuals with disabilities in light of disability-related factors at the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability in Iraq. The results indicated significant psychological burdens experienced by spouses of persons with disabilities. According to the measurement scale applied, 81.6% of these women reported high levels of psychological burden, with a mean score of 73.87±19.44. This high percentage highlights the extent of the psychological difficulties experienced by these women. Although the majority of them feel intense stress, the degree and type of this stress can vary greatly, as the large standard deviation demonstrates. Several reasons contribute to the psychological stress endured by spouses of persons with disabilities. Stress levels are often elevated due to caregiving obligations, the emotional impact of witnessing a loved one in distress, and the potential for financial problems. Given the chronic nature of many disabilities, psychological stress persists as a result of these stressors. Feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and sadness may arise from this situation, further increasing the burden.

Previous research has repeatedly demonstrated the significant psychological stress experienced by wives and other caregivers of people with disabilities. Providing care to individuals with long-term illnesses or disabilities often results in high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among caregivers. Research from South Australia indicates that compared with non-carers, caregivers of people with chronic illnesses experience significantly greater levels of psychological burden [18]. This finding is consistent with recent research highlighting the substantial psychological impact endured by spouses of individuals with disabilities.

Additionally, a Belgian study supported the idea that caregiving is associated with poor mental health outcomes. The study revealed that constant care demands often cause emotional stress for caregivers, which can lead to chronic stress and burnout [19]. This is particularly important for spouses of people with disabilities, who often have to provide long-term care without downtime or adequate assistance.

Moreover, studies conducted in China have found that a lack of financial resources and social support may exacerbate the psychological burden faced by caregivers. Caregivers who feel lonely or lack adequate support networks are more likely to experience elevated stress levels and mental health problems [20]. This finding is consistent with existing research suggesting that a lack of external support and social acceptance of caregiving roles may contribute to the significant psychological burden experienced by spouses of individuals with disabilities.

Previous research also supports the heterogeneity in these women’s experiences, based on the large standard deviation in the present results. For example, a systematic review found that the psychological impacts on caregivers may vary widely based on the degree of disability, the availability of support systems, and the coping strategies employed by caregivers [21]. This variation underscores the importance of providing individualized treatment and support plans to meet the specific needs of each caregiver.

The current study’s findings are consistent with a body of previous research that highlights the significant psychological harms endured by caregivers (especially spouses) of people with disabilities. Previous research has drawn attention to the emotional toll, ongoing stress, and diversity of experiences that caregivers face, underscoring the need to improve support networks and social recognition of their vital role. By addressing these issues, the overall health of caregivers can be enhanced, and their psychological burden can be reduced.

The results indicated the significant influence of factors related to economic status, as well as the degree and duration of a person’s condition, on the psychological difficulties experienced by spouses of persons with disabilities. These data reveal a strong and statistically significant relationship between these factors and caregivers’ mental health, suggesting that these women’s psychological struggles are likely to worsen as their financial burden, the severity and duration of the disability, and the disability itself increase.

Wives of people with disabilities experienced an increase in psychological difficulties for every monthly reduction in income. This research highlights the significant impact that financial stability has on mental health. Stress, anxiety, and depression can be exacerbated by economic instability, especially for individuals already managing caregiving demands. The emotional and psychological toll of being unable to meet financial obligations is likely to be worsened by this, underscoring the need for resources and targeted financial assistance to alleviate this burden. This is supported by a wealth of existing literature. For example, research suggests that caregivers experiencing financial difficulties are more likely to report higher levels of stress, anxiety, and hopelessness. Financial stress is a strong predictor of depressive symptoms in Hong Kong, emphasizing the need for financial support systems to alleviate the pressures of caring for older individuals [22]. Similarly, in Galveston, USA, it was noted that the presence of financial challenges may make caregiving more emotionally and mentally stressful, highlighting the importance of financial measures to enhance caregivers’ mental health [23].

The psychological burdens of these couples increase with their degree of vulnerability. There is often a need for more comprehensive and ongoing care for those with severe disabilities, which can be mentally and physically exhausting. The amount and type of caregiving responsibilities appear to be important determinants of mental health, as evidenced by the observed rise in psychological burden associated with increasing severity of disability. This highlights the need for comprehensive support networks, such as counseling, community services, and respite care, to assist these caregivers in managing the additional challenges that come with more severe disabilities. Previous studies also support these conclusions. According to a Korean study, caregivers of individuals with more severe disabilities experience higher levels of caregiver sadness and stress [24]. Stress and emotional exhaustion for caregivers can be exacerbated by the added responsibilities of caring for someone with a severe disability, such as increased medical appointments and physical care needs. Additionally, according to a study conducted in Victoria, Australia, there is a link between increased severity of disability and heightened caregiver suffering. This underscores the need for improved support services for those caring for people with severe disabilities [25].

Finally, women with disabilities experience more psychological problems every year when their husbands have a disability. Long-term caregiving duties without adequate support can gradually weaken mental resilience, leading to chronic stress and burnout. This research underscores the importance of long-term support plans for caregivers, ensuring they have continued access to support networks, mental health treatments, and other resources to maintain their well-being over time. The literature similarly reflects these findings. Long-term caregiving has been linked to ongoing stress and an increased likelihood of developing mental health problems. Chronic caregiving has been associated with severe psychological morbidity, including higher levels of anxiety and sadness, according to German research [26]. Moreover, burnout is common among long-term caregivers, highlighting the need for ongoing assistance and short-term respite care to help them cope with their obligations over time [1].

Evidence from previous research highlights the urgent need for comprehensive support systems to address the short- and long-term financial difficulties experienced by caregivers of disabled individuals. When these findings are compared with previous studies, it becomes clear that targeted treatments are necessary to reduce the psychological costs to this vulnerable group.

Our findings indicated that there are noticeable differences in the psychological burdens borne by spouses of people with disabilities, depending on the affected part of the body and the cause of the condition. Compared with wives whose husbands acquired their disabilities in other ways, wives of husbands who suffered war-related impairments bear much greater psychological costs. There are several reasons for this increased burden. Veterans and their spouses are not the only ones affected by the complex emotional and psychological ramifications resulting from war-related injuries, which often include trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. These women may experience greater emotional stress and a stronger sense of duty or helplessness due to constant reminders of war and a higher level of war casualties in the community. Furthermore, they may worry about their husbands’ recurring mental health crises or medical problems due to the severe and unexpected nature of combat injuries.

Studies have consistently shown the extreme psychological stress that wives of war veterans experience. For example, a study conducted in Falls Church, Virginia, USA, discovered that, compared with wives of non-combatant veterans, spouses of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exhibit greater degrees of emotional burdens, hopelessness, and anxiety [27]. This is attributed to the widespread effects of PTS, which impacts not only the veteran but also his or her family members, leading to a tense and unstable home life. Similarly, research conducted in Garden City, New York, USA, found that wives of veterans with mental health problems experience significant declines in their psychological well-being, supporting the notion that husbands suffer profound emotional effects from war-related disabilities [28].

In addition, the affected part due to the disability has a significant impact on psychological difficulties. According to our results, wives of individuals who suffer from disabilities in the lower limbs experienced more psychological problems than wives of those with disabilities in the upper limbs. Functional and caregiving consequences associated with different types of disabilities may explain this differentiation. Disabilities that affect the lower extremities often result in severe mobility issues that require more intensive physical care and may necessitate changes in living arrangements. Increased stress and emotional fatigue may arise from heightened caregiving responsibilities, as well as the potential need for assistance with simple daily tasks, such as dressing, washing, and using the bathroom. On the other hand, limitations in the upper extremities, although still significant, provide more freedom of movement and require less intensive physical care, thereby reducing the psychological burden on the husband. This is well supported by Korean research, which found that higher levels of caregiving burden are experienced by those who provide care for individuals with spinal cord injuries, which predominantly affect the lower extremities. Due to the increased intensity of caregiving duties and the frequent need for constant and comprehensive assistance from the care recipient, this stress has both physical and emotional components [29]. Furthermore, the obligations of providing physical care and the emotional burden of witnessing loved ones lose their independence have increased stress and deteriorated the quality of life for family members of individuals with significant mobility impairments, especially for spouses [1, 30, 31].

The observed differences in psychological burdens between spouses of individuals with disabilities, based on the type and location of their disability, are strongly supported by these previous investigations. They emphasize the need for support networks tailored to address the practical and emotional difficulties faced by caregivers. These customized interventions are essential for reducing the rising psychological costs and improving the overall health of these couples.

Generalizing the study results to the psychological difficulties experienced by spouses of individuals with disabilities, while taking disability-related characteristics into account, is one potential limitation. The sample did not accurately reflect the range of couples’ experiences across different social, cultural, and geographic contexts. Furthermore, because the study relied solely on self-report measures, response bias may have been introduced, as participants might over-report their experiences based on their perceptions of the questions or how desirable they believe the information is. Additionally, the cross-sectional study design makes it difficult to determine a cause-and-effect relationship or to assess how these women’s psychological burdens change over time. Longitudinal approaches and more diverse participant groups may enhance the validity and applicability of the findings in future studies. The results underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to support these women, including financial assistance programs, psychological support services, and initiatives to improve the quality of life for families affected by disabilities. Policymakers and healthcare providers should prioritize these interventions to alleviate the psychological stress faced by wives of individuals with disabilities and improve their overall well-being.

Conclusions

The majority of wives people with disability suffer from significant psychological burdens and low monthly income, the severity of the disability, and the duration of the disability greatly exacerbate these burdens.

Acknowledgments: We are incredibly appreciative of all the wives of individuals with disabilities who participated in this study and kindly shared their knowledge and experiences. Their candor regarding their struggles has been extremely helpful to our research.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Nursing/Babylon University (122, dated April/5/2024).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Hrefish ZA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (50%); Hussein MA (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%)

Funding/Support: The present study was not financially supported.

It is estimated that over a billion people around the globe live with some type of disability. The primary causes of these disabilities are often linked to chronic health conditions, such as visual impairment resulting from diabetes. Spouses of individuals with disabilities experience severe and complex psychological difficulties that vary depending on a set of parameters associated with the disability. Emotional exhaustion, anxiety, depression, and social isolation are common manifestations of these stressors [1]. The physical demands and chronic nature of the disability exacerbate the emotional burden of caregiving, which women typically bear. This caregiving dynamic often leads to feelings of being trapped and losing independence, as caring for a disabled spouse can involve many difficult and stressful tasks [2].

These mental costs result from several disability-related problems. The type of condition and its severity are important factors to consider. For example, disabilities, such as severe motor impairment or cognitive disorders that require regular monitoring or significant physical care place a greater burden on caregivers [3]. Long-term or permanent disabilities cause constant stress and progressively reduce the caregiver’s flexibility, making the duration of the condition a crucial issue. Wives often face financial struggles and social rejection, which can lead to feelings of helplessness and despair. These factors, along with the social stigma and economic obstacles associated with disability, further exacerbate psychological burdens [4].

Moreover, a woman’s psychological effects may be greatly influenced by her marital status before the onset of the disability. A strong and stable marriage can act as a stress reliever and reduce some of the emotional strain [5]. On the other hand, the caregiver’s perception of loneliness and psychological pain may be exacerbated by pre-existing marital discord or a lack of emotional closeness [6]. Spouses of individuals with disabilities often find significant relief from their limitations through their social support networks, underscoring the need for comprehensive support systems to address these psychological burdens. Such networks include friends, extended family, and community services [7].

Disability as an interpersonal experience affects the people patients are close with. Close relationship partners show the same levels of psychological distress as patients. For example, meta-analytic data suggest comparable patient and spouse psychological distress, which means that distress does not significantly differ between them. Although other family members also suffer, romantic partners are more at risk of developing distress related to the patient's impairment. Spouses of individuals with disabilities face significant psychological challenges that are influenced by a complex web of interconnected elements related to both the disability and the larger social and relational environment. A comprehensive strategy is needed to address these challenges, including social services, psychological support, and policies designed to reduce caregiving stress and improve the quality of life for individuals with disabilities and their spouses [1, 8]. We need to recognize the genuine needs of individuals with disabilities, as well as those of the caregivers who share their lives. Among these caregivers is the wife, who experiences similar challenges and circumstances as any other wife; however, the burdens faced by wives of individuals with disabilities are more intricate and significant, encompassing various economic, psychological, and social pressures. Due to their husband’s disability, many women are compelled to take on a productive role in addition to their responsibilities in managing the household and educating their children [9]. Furthermore, the psychological burdens imposed by society, stemming from a limited perception of the disabled individual and their family within a traditional cultural framework, complicate and hinder the adjustment process [10]. Caring for a sick or disabled family member can have negative emotional, social, and financial effects on the caregiver. In Iraq, strong family bonds and the importance of traditions are prevalent, leading family members to share both happiness and hardship. This unique aspect of Iraqi culture means that care for individuals with disabilities is a lifelong commitment. Typically, the primary caregivers are first-degree relatives, often wives, who not only help with the care of the disabled but also provide emotional support. While this role can bring emotional fulfillment to the caregiver, challenging living conditions can lead to various difficulties [11].

Several factors influence the burdens experienced by wives of individuals with disabilities. The challenges faced by illiterate wives differ from those of wives who are primary, secondary, or college graduates; specifically, lower educational attainment correlates with greater burdens. This relationship is largely attributed to economic circumstances, as many individuals without formal education lack employment and encounter financial difficulties. Consequently, there is little difference in burdens between those with low and moderate incomes, while those with higher incomes tend to experience fewer burdens than those with limited financial resources. The findings of this study align with existing literature, which indicates that higher education levels are associated with reduced caregiver burdens. For instance, Papastavrou et al. found that primary school graduates faced a significantly higher caregiver burden [12]. Stenberg et al. noted that caregivers with a bachelor’s degree reported a disproportionately low financial burden compared to others [13], and Shieh et al. indicated that higher education levels predicted a significantly lower caregiver burden [14]. Furthermore, Park et al. demonstrated that individuals with higher education levels received much greater family support [15]. A study in Mazandaran showed that there are many psychological problems in the spouses of neuropsychiatric veterans and the spouses of chemical veterans of the Iran-Iraq war; however, the results showed no significant change in the two groups based on age, number of children, percentage of injury, and literacy level [16].

As the number of individuals living with disabilities increases, a greater number of relationship dynamics will be affected by the implications of disability. Women encounter numerous challenges and issues stemming from gender distinctions rooted in traditional culture, and these challenges are particularly pronounced for the wives of individuals with disabilities. Assisting the wives of the disabled in adapting and alleviating these burdens, difficulties, and gaps in support is a crucial priority for easing their struggles and facilitating their integration into society. Therefore, this study assessed the psychological burden among wives of individuals with disabilities in light of disability-related factors at the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability in Iraq.

Instrument and Methods

Design and sample

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability from April 2 to June 12, 2024. A sample of 250 wives of individuals with disabilities in Babylon Province was used for the study; this sample constituted about 10% of the total study population. From the list of spouses registered with the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability, simple random sampling was employed to select the sample. According to the monthly reviews, there were 992 views in total and a quarter of the study community was appropriately selected.

Research tools

A checklist collected socio-demographic factors, including the age of the spouses, level of education, and monthly income. Factors associated with disability included the types of disabilities, the causes of disabilities, and the duration of disabilities. The 22 items of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (ZCBS), developed by Zarit et al. in 1980 [17], measured how caregiving affects the caregiver. Each item is rated as never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), very often (3), and usually almost always (4) on a five-point Likert scale. The maximum score on the scale is 88, while the lowest possible score is 0. A high score indicates an increased burden on spouses. The validity and reliability of the scale were examined in Iraq by Malih Radhi et al., with results showing that the test-retest reliability was 0.81 and that the internal consistency ranged from 0.87 [1].

The reliability of the research tool was evaluated by conducting a pilot study that included 20 respondents, or 10% of the study sample. When the participants visited the Babylon Center for Rehabilitation of the Disabled, the researcher provided a brief introduction and asked them to complete a questionnaire to share their thoughts and participate in the study. Next, the researcher presented a summary of the study objectives and title to assess the clarity of the study and the ease of understanding of the questionnaire. It was expected that each form would take about 20 minutes to complete. After examining the data, the responses from the pilot study were excluded from the sample without making any changes. In our research, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.81, indicating a reasonable degree of reliability.

Data collection

The data were collected over a full month at the Babylon Center for Rehabilitation of the Disabled. The researchers conducted individual interviews with each study participant to explain the project’s goal and obtain verbal consent. Participant interviews were used to collect data according to the inclusion criteria.

Participants studying psychological difficulties among couples with disabilities must meet several requirements to be considered for inclusion. The first requirement is that they must be adult females (18 years and older) currently married to someone with a recognized disability, such as a physical, intellectual, or sensory disability. To ensure that the impairment has a significant impact on daily functioning, it must be medically verified and have persisted for at least six months. Furthermore, participants must live with their spouses with disabilities to ensure the sharing of daily experiences and caregiving obligations. In addition to being willing to participate in surveys or interviews about their psychological and emotional experiences, they must also be able to provide informed consent. Participants must have been providing care for at least six months to demonstrate that they have significant experience managing the psychological responsibilities that come with the role.

Those who did not meet the age or gender requirements were not allowed to participate in the study, following the exclusion criteria. Spouses of individuals with short-term disabilities (less than six months) were not eligible, as the study focused more on the long-term psychological effects. Furthermore, individuals who were not living with a spouse with a disability were not accepted, as their caregiving experiences may differ significantly from those of individuals who live with their spouses. To further ensure the validity of the data, women with serious mental health issues or cognitive impairments that prevent them from providing informed consent or accurately recalling their experiences were excluded. Finally, to avoid biases or confounding effects in the data collected, participants involved in other psychological research on caregiving were not permitted to participate.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20 software. Numbers and percentages were used to rank parameters, while the mean and standard deviation were used to statistically describe continuous parameters. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were employed to test for normality. In addition, associations and predictors among study parameters were examined using simple linear regression and the Kruskal-Wallis test. A significance threshold of 0.05 was applied to the statistical interpretations.

Findings

The mean age of participants was 37.93±10.02 years. Notably, most samples were secondary school graduates (45.6%). The majority of the study sample reported a low monthly income (84.0%). Additionally, 81.6% expressed a high severity of disability. War was identified as the major cause of disabilities (76.8%), with lower limb disabilities accounting for 82.0%. The average duration of disabilities was 9.87±5.09 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of demographic and disability-related factors

A significant proportion (204, 81.6%) of the wives of people with disabilities reported a high psychological burden, followed by those indicating moderate (26, 10.4%) and low (20, 8.0%) levels. The total mean score of psychological burdens was 73.87±19.44.

The linear regression analysis indicated the predicted relationship between psychological burdens among wives of people with disabilities and their monthly income, severity of disabilities, and duration of disabilities (Table 2).

Table 2. Linear regression analysis of the study parameters to predict psychological burdens

Every decrease in monthly income was associated with an increase in psychological burdens among the wives of disabled individuals by 29.28 times. When the disability became severe, there was an increase in psychological burdens among the wives of disabled individuals by 27.83 times. Also, every increase in the duration of disability was associated with an increase in psychological burdens among the wives of disabled individuals by 2.340 times.

The findings of the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated statistically significant differences in psychological burdens among wives of people with disabilities based on the reasons for their husbands’ disabilities (p=0.001) and the affected parts due to disabilities, whether upper or lower limbs (p=0.001; Table 3).

Table 3. Differences in psychological burdens based on the cause of disability and affected parts due to disability

Discussion

This study assessed the psychological burden among wives of individuals with disabilities in light of disability-related factors at the Babylon Rehabilitation Center for Disability in Iraq. The results indicated significant psychological burdens experienced by spouses of persons with disabilities. According to the measurement scale applied, 81.6% of these women reported high levels of psychological burden, with a mean score of 73.87±19.44. This high percentage highlights the extent of the psychological difficulties experienced by these women. Although the majority of them feel intense stress, the degree and type of this stress can vary greatly, as the large standard deviation demonstrates. Several reasons contribute to the psychological stress endured by spouses of persons with disabilities. Stress levels are often elevated due to caregiving obligations, the emotional impact of witnessing a loved one in distress, and the potential for financial problems. Given the chronic nature of many disabilities, psychological stress persists as a result of these stressors. Feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and sadness may arise from this situation, further increasing the burden.

Previous research has repeatedly demonstrated the significant psychological stress experienced by wives and other caregivers of people with disabilities. Providing care to individuals with long-term illnesses or disabilities often results in high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among caregivers. Research from South Australia indicates that compared with non-carers, caregivers of people with chronic illnesses experience significantly greater levels of psychological burden [18]. This finding is consistent with recent research highlighting the substantial psychological impact endured by spouses of individuals with disabilities.

Additionally, a Belgian study supported the idea that caregiving is associated with poor mental health outcomes. The study revealed that constant care demands often cause emotional stress for caregivers, which can lead to chronic stress and burnout [19]. This is particularly important for spouses of people with disabilities, who often have to provide long-term care without downtime or adequate assistance.

Moreover, studies conducted in China have found that a lack of financial resources and social support may exacerbate the psychological burden faced by caregivers. Caregivers who feel lonely or lack adequate support networks are more likely to experience elevated stress levels and mental health problems [20]. This finding is consistent with existing research suggesting that a lack of external support and social acceptance of caregiving roles may contribute to the significant psychological burden experienced by spouses of individuals with disabilities.

Previous research also supports the heterogeneity in these women’s experiences, based on the large standard deviation in the present results. For example, a systematic review found that the psychological impacts on caregivers may vary widely based on the degree of disability, the availability of support systems, and the coping strategies employed by caregivers [21]. This variation underscores the importance of providing individualized treatment and support plans to meet the specific needs of each caregiver.

The current study’s findings are consistent with a body of previous research that highlights the significant psychological harms endured by caregivers (especially spouses) of people with disabilities. Previous research has drawn attention to the emotional toll, ongoing stress, and diversity of experiences that caregivers face, underscoring the need to improve support networks and social recognition of their vital role. By addressing these issues, the overall health of caregivers can be enhanced, and their psychological burden can be reduced.

The results indicated the significant influence of factors related to economic status, as well as the degree and duration of a person’s condition, on the psychological difficulties experienced by spouses of persons with disabilities. These data reveal a strong and statistically significant relationship between these factors and caregivers’ mental health, suggesting that these women’s psychological struggles are likely to worsen as their financial burden, the severity and duration of the disability, and the disability itself increase.

Wives of people with disabilities experienced an increase in psychological difficulties for every monthly reduction in income. This research highlights the significant impact that financial stability has on mental health. Stress, anxiety, and depression can be exacerbated by economic instability, especially for individuals already managing caregiving demands. The emotional and psychological toll of being unable to meet financial obligations is likely to be worsened by this, underscoring the need for resources and targeted financial assistance to alleviate this burden. This is supported by a wealth of existing literature. For example, research suggests that caregivers experiencing financial difficulties are more likely to report higher levels of stress, anxiety, and hopelessness. Financial stress is a strong predictor of depressive symptoms in Hong Kong, emphasizing the need for financial support systems to alleviate the pressures of caring for older individuals [22]. Similarly, in Galveston, USA, it was noted that the presence of financial challenges may make caregiving more emotionally and mentally stressful, highlighting the importance of financial measures to enhance caregivers’ mental health [23].

The psychological burdens of these couples increase with their degree of vulnerability. There is often a need for more comprehensive and ongoing care for those with severe disabilities, which can be mentally and physically exhausting. The amount and type of caregiving responsibilities appear to be important determinants of mental health, as evidenced by the observed rise in psychological burden associated with increasing severity of disability. This highlights the need for comprehensive support networks, such as counseling, community services, and respite care, to assist these caregivers in managing the additional challenges that come with more severe disabilities. Previous studies also support these conclusions. According to a Korean study, caregivers of individuals with more severe disabilities experience higher levels of caregiver sadness and stress [24]. Stress and emotional exhaustion for caregivers can be exacerbated by the added responsibilities of caring for someone with a severe disability, such as increased medical appointments and physical care needs. Additionally, according to a study conducted in Victoria, Australia, there is a link between increased severity of disability and heightened caregiver suffering. This underscores the need for improved support services for those caring for people with severe disabilities [25].

Finally, women with disabilities experience more psychological problems every year when their husbands have a disability. Long-term caregiving duties without adequate support can gradually weaken mental resilience, leading to chronic stress and burnout. This research underscores the importance of long-term support plans for caregivers, ensuring they have continued access to support networks, mental health treatments, and other resources to maintain their well-being over time. The literature similarly reflects these findings. Long-term caregiving has been linked to ongoing stress and an increased likelihood of developing mental health problems. Chronic caregiving has been associated with severe psychological morbidity, including higher levels of anxiety and sadness, according to German research [26]. Moreover, burnout is common among long-term caregivers, highlighting the need for ongoing assistance and short-term respite care to help them cope with their obligations over time [1].

Evidence from previous research highlights the urgent need for comprehensive support systems to address the short- and long-term financial difficulties experienced by caregivers of disabled individuals. When these findings are compared with previous studies, it becomes clear that targeted treatments are necessary to reduce the psychological costs to this vulnerable group.

Our findings indicated that there are noticeable differences in the psychological burdens borne by spouses of people with disabilities, depending on the affected part of the body and the cause of the condition. Compared with wives whose husbands acquired their disabilities in other ways, wives of husbands who suffered war-related impairments bear much greater psychological costs. There are several reasons for this increased burden. Veterans and their spouses are not the only ones affected by the complex emotional and psychological ramifications resulting from war-related injuries, which often include trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. These women may experience greater emotional stress and a stronger sense of duty or helplessness due to constant reminders of war and a higher level of war casualties in the community. Furthermore, they may worry about their husbands’ recurring mental health crises or medical problems due to the severe and unexpected nature of combat injuries.

Studies have consistently shown the extreme psychological stress that wives of war veterans experience. For example, a study conducted in Falls Church, Virginia, USA, discovered that, compared with wives of non-combatant veterans, spouses of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exhibit greater degrees of emotional burdens, hopelessness, and anxiety [27]. This is attributed to the widespread effects of PTS, which impacts not only the veteran but also his or her family members, leading to a tense and unstable home life. Similarly, research conducted in Garden City, New York, USA, found that wives of veterans with mental health problems experience significant declines in their psychological well-being, supporting the notion that husbands suffer profound emotional effects from war-related disabilities [28].

In addition, the affected part due to the disability has a significant impact on psychological difficulties. According to our results, wives of individuals who suffer from disabilities in the lower limbs experienced more psychological problems than wives of those with disabilities in the upper limbs. Functional and caregiving consequences associated with different types of disabilities may explain this differentiation. Disabilities that affect the lower extremities often result in severe mobility issues that require more intensive physical care and may necessitate changes in living arrangements. Increased stress and emotional fatigue may arise from heightened caregiving responsibilities, as well as the potential need for assistance with simple daily tasks, such as dressing, washing, and using the bathroom. On the other hand, limitations in the upper extremities, although still significant, provide more freedom of movement and require less intensive physical care, thereby reducing the psychological burden on the husband. This is well supported by Korean research, which found that higher levels of caregiving burden are experienced by those who provide care for individuals with spinal cord injuries, which predominantly affect the lower extremities. Due to the increased intensity of caregiving duties and the frequent need for constant and comprehensive assistance from the care recipient, this stress has both physical and emotional components [29]. Furthermore, the obligations of providing physical care and the emotional burden of witnessing loved ones lose their independence have increased stress and deteriorated the quality of life for family members of individuals with significant mobility impairments, especially for spouses [1, 30, 31].

The observed differences in psychological burdens between spouses of individuals with disabilities, based on the type and location of their disability, are strongly supported by these previous investigations. They emphasize the need for support networks tailored to address the practical and emotional difficulties faced by caregivers. These customized interventions are essential for reducing the rising psychological costs and improving the overall health of these couples.

Generalizing the study results to the psychological difficulties experienced by spouses of individuals with disabilities, while taking disability-related characteristics into account, is one potential limitation. The sample did not accurately reflect the range of couples’ experiences across different social, cultural, and geographic contexts. Furthermore, because the study relied solely on self-report measures, response bias may have been introduced, as participants might over-report their experiences based on their perceptions of the questions or how desirable they believe the information is. Additionally, the cross-sectional study design makes it difficult to determine a cause-and-effect relationship or to assess how these women’s psychological burdens change over time. Longitudinal approaches and more diverse participant groups may enhance the validity and applicability of the findings in future studies. The results underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to support these women, including financial assistance programs, psychological support services, and initiatives to improve the quality of life for families affected by disabilities. Policymakers and healthcare providers should prioritize these interventions to alleviate the psychological stress faced by wives of individuals with disabilities and improve their overall well-being.

Conclusions

The majority of wives people with disability suffer from significant psychological burdens and low monthly income, the severity of the disability, and the duration of the disability greatly exacerbate these burdens.

Acknowledgments: We are incredibly appreciative of all the wives of individuals with disabilities who participated in this study and kindly shared their knowledge and experiences. Their candor regarding their struggles has been extremely helpful to our research.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Nursing/Babylon University (122, dated April/5/2024).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Hrefish ZA (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher/Discussion Writer (50%); Hussein MA (Second Author), Methodologist/Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (50%)

Funding/Support: The present study was not financially supported.

Keywords:

References

1. Malih Radhi M, Juma Elywy G, Khyoosh Al-Eqabi QA. Burdens among wives of disabled people in the light of some social variables. Iran Rehabil J. 2023;21(3):473-84. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/irj.21.3.1765.3]

2. Elywy GJ, Malih Radhi M, Khyoosh Al-Eqabi QA. Relationship between social support and self-hardiness among breast cancer women in Nasiriyah, Iraq. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023;73(9):S9-14. [Link] [DOI:10.47391/JPMA.IQ-02]

3. Reynolds MC, Palmer SB, Barton KN. Supporting active aging for persons with severe disabilities and their families across the life course. Res Pract Pers Sev Disabil. 2019;44(4):211-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1540796919880561]

4. Cejalvo E, Marti-Vilar M, Merino-Soto C, Aguirre-Morales MT. Caregiving role and psychosocial and individual factors: A systematic review. Healthcare. 2021;9(12):1690. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare9121690]

5. Bertschi IC, Meier F, Bodenmann G. Disability as an interpersonal experience: A systematic review on dyadic challenges and dyadic coping when one partner has a chronic physical or sensory impairment. Front Psychol. 2021;12:624609. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624609]

6. Malih Radhi M, Khyoosh Al-Eqabi QA, Hindi NK. Rehabilitation problems of people with motor disabilities at Babylon center for rehabilitation of the disabled. Med J Babylon. 2023;20(4):838-43. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/MJBL.MJBL_674_23]

7. Juma Elywy G, Malih Radhi M, Khyoosh Al-Eqabi QA. Social support and its association with the quality of life (QoL) of amputees. Iran Rehabil J. 2022;20(2):253-60. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/irj.20.2.1784.1]

8. Khyoosh Al-Eqabi QA, Niazy SM, Malih Radhi M. Amputation-related factors influencing activities of daily living among amputees. Iran J War Public Health. 2024;16(2):1001-9. [Link]

9. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2]

10. Iudici A, Favaretto G, Turchi GP. Community perspective: How volunteers, professionals, families and the general population construct disability: Social, clinical and health implications. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(2):171-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.11.014]

11. Malih Radhi M, Juma Elywy G, Abbas Khyoosh Al-Eqabi Q. Burdens Among Wives of Disabled People in the Light of Some Social Variables. Iran Rehabil J. 2023;21(3):473-484. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/irj.21.3.1765.3]

12. Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H. Exploring the other side of cancer care: the informal caregiver. Eur J Oncology Nurs. 2009;13(2):128-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ejon.2009.02.003]

13. Stenberg U, Cvancarova M, Ekstedt M, Olsson M, Ruland C. Family caregivers of cancer patients: perceived burden and symptoms during the early phases of cancer treatment. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53(3):289-309. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00981389.2013.873518]

14. Shieh SC, Tung HS, Liang SY. Social support as influencing primary family caregiver burden in Taiwanese patients with colorectal cancer. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(3):223-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01453.x]

15. Park CH, Shin DW, Choi JY, Kang J, Baek YJ, Mo HN, Lee MS, Park SJ, Park SM, Park S. Determinants of the burden and positivity of family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients in Korea. Psycho‐Oncol. 2012;21(3):282-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/pon.1893]

16. Mirzamani SM, Karaminia R, Azad-Marzabadi E, Salimi SH, Hosseini-Sangtrashani SA. Being a wife of a veteran with psychiatric problem or chemical warfare exposure: A preliminary report from Iran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1(2):65-9. [Link]

17. Zarit SH. Aging & mental disorders (psychological approaches to assessment & treatment). New York: Simon and Schuster; 1980. [Link]

18. Stacey AF, Gill TK, Price K, Taylor AW. Differences in risk factors and chronic conditions between informal (family) carers and non-carers using a population-based cross-sectional survey in South Australia. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e020173. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020173]

19. Gérain P, Zech E. Informal caregiver burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1748. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01748]

20. Sit HF, Huang L, Chang K, Chau WI, Hall BJ. Caregiving burden among informal caregivers of people with disability. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(3):790-813. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12434]

21. Fairfax A, Brehaut J, Colman I, Sikora L, Kazakova A, Chakraborty P, et al. A systematic review of the association between coping strategies and quality of life among caregivers of children with chronic illness and/or disability. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):215. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12887-019-1587-3]

22. Sun Q, Wang Y, Lu N, Lyu S. Intergenerational support and depressive symptoms among older adults in rural China: The moderating roles of age, living alone, and chronic diseases. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):83. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12877-021-02738-1]

23. Theng B, Tran JT, Serag H, Raji M, Tzeng HM, Shih M, et al. Understanding caregiver challenges: A comprehensive exploration of available resources to alleviate caregiving burdens. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43052. [Link] [DOI:10.7759/cureus.43052]

24. Uhm KE, Jung H, Woo MW, Kwon HE, Oh-Park M, Lee BR, et al. Influence of preparedness on caregiver burden, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of people with disabilities. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1153588. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1153588]

25. He C, Evans N, Graham H, Milner K. Group-based caregiver support interventions for children living with disabilities in low-and-middle-income countries: Narrative review and analysis of content, outcomes, and implementation factors. J Glob Health. 2024;14:04055. [Link] [DOI:10.7189/jogh.14.04055]

26. Janson P, Willeke K, Zaibert L, Budnick A, Berghöfer A, Kittel-Schneider S, et al. Mortality, morbidity and health-related outcomes in informal caregivers compared to non-caregivers: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):5864. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19105864]

27. Kelber MS, Liu X, O'Gallagher K, Stewart LT, Belsher BE, Morgan MA, et al. Women in combat: The effects of combat exposure and gender on the incidence and persistence of posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;133:16-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.010]

28. Marini CM, Fiori KL, Wilmoth JM, Pless Kaiser A, Martire LM. Psychological adjustment of aging Vietnam veterans: The role of social network ties in reengaging with wartime memories. Gerontology. 2020;66(2):138-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000502340]

29. Lee SJ, Kim MG, Kim JH, Min YS, Kim CH, Kim KT, et al. Factor analysis affecting degree of depression in family caregivers of patients with spinal cord injury: A cross-sectional pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10878. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph191710878]

30. Malih Radhi M, Zair Balat K. Health literacy and its association with medication adherence in patients with hypertension: A mediating role of social support. Iran Rehabil J. 2024;22(1):117-28. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/irj.22.1.1989.1]

31. Malih Radhi M, Abd RK, Khyoosh Al-Eqabi QA. The body image and its relation to self-esteem among amputation patients at Artificial Limbs Hospital at Kut City, Iraq. J Public Health Afr. 2022;13(4):a411. [Link] [DOI:10.4081/jphia.2022.1228]