Volume 16, Issue 1 (2024)

Iran J War Public Health 2024, 16(1): 9-15 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/05/28 | Accepted: 2024/01/10 | Published: 2024/01/30

Received: 2023/05/28 | Accepted: 2024/01/10 | Published: 2024/01/30

How to cite this article

Zohrehvand M, Rahmati F, Saffari M, Dowran B. Literacy of Suicide Scale in the Iranian Military Youth; The Validity and Reliability of the Persian Version. Iran J War Public Health 2024; 16 (1) :9-15

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1351-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1351-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran

2- Health Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- “Health Research Center, Life Style Institute” and “Health Education Department, Faculty of Health”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Health Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- “Health Research Center, Life Style Institute” and “Health Education Department, Faculty of Health”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (610 Views)

Introduction

Suicide is a significant public health issue [1] and ranks among the leading causes of death globally [2]. It is also one of the top ten causes of death and lost years of life in many parts of the world [3]. The term "suicide" refers to death caused by self-inflicted injury with the intent to die [4].

The World Health Organization has identified suicide as a public health priority, stating that suicide prevention is essential in all countries. Key underlying factors of suicide include predisposing physical diseases, mental disorders, demographic factors, economic factors, environmental factors, issues related to refuge and immigration, emotional-communication problems, incarceration, and family issues [5, 6].

Every year, approximately 700,000 individuals die from suicide worldwide. Suicide can occur at any point throughout the life cycle and stands as the fourth leading cause of death among individuals aged 15-29 years globally [7]. Common methods of suicide include the use of firearms, hanging, suffocation, drowning, carbon monoxide poisoning, jumping, and drug overdose. The incidence of suicide has been rising gradually worldwide, particularly in European countries. For example, in the Netherlands, the number of suicides increases annually by between 3% and 6% [8].

Suicide rates are also increasing in Iran. A meta-analysis concluded that in recent decades, Iran has seen the largest increase in suicide rates among Islamic and Eastern Mediterranean countries [9]. The provinces of Ilam, Lorestan, Hamadan, Kurdistan, and Kermanshah have the highest rates of completed suicides, while the provinces of Isfahan, Yazd, Semnan, and Qom have the highest rates of attempted suicide and the lowest rates of completed suicide [10]. Furthermore, findings from Zarani and Ahmadi's study indicate that contrary to global statistics, suicide attempts are more prevalent among Iranian men [11].

Suicidal behavior is categorized into four main types: suicidal thoughts, planning, attempts, and completed suicide. Suicidal ideation involves harboring thoughts and plans for suicide without necessarily acting on them. In the planning stage, an individual makes preparations by securing the means or location for suicide [12].

Suicide can also occur among soldiers. In a survey, the suicide rate for military personnel was reported as twelve per 100,000 people, compared to nine per 100,000 among civilians [13]. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has reported that 17 veterans die by suicide every day. Consistent with this, studies have estimated that suicide is more common among military personnel than civilians [14, 15].

Furthermore, suicide literacy is crucial both in the general population and particularly among military personnel. Suicide literacy refers to the understanding of the causes, risk factors, signs, symptoms, and treatments of suicide. This knowledge is vital as it can help reduce the prevalence of suicide by encouraging individuals to seek professional help. In contrast, incorrect or incomplete knowledge may cause hesitance in seeking the necessary support for suicide prevention [16]. Generally, suicide literacy is insufficient [17], leading to the stigmatization of suicide as a taboo topic and the neglect of its warning signs [18].

Studies have shown that the quality of nursing care for patients who have attempted suicide can be influenced by various factors, including the nurses' knowledge about suicide, their ability to assess suicide risk, and their professional experiences, attitudes, and beliefs about suicide as a taboo subject [19]. Additional research also confirms that suicide literacy effectively improves attitudes, reduces stigmatization, and decreases judgment toward affected individuals [20-23].

As a result, it is crucial to identify groups with limited literacy in this field to promote mental health programs. By enhancing public and professional awareness about suicide, we can better manage and prevent it. One tool that can be used to evaluate the level of suicide literacy is a questionnaire. The Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS) by Calear et al. is a suitable tool for this purpose [16]. This scale is valuable and practical due to its reference scale and the absence of a similar questionnaire in Iran. The LOSS contains 27 items; twelve items are taken from the Revised Facts on Suicide Quiz (RFOS) developed by Hubbard and McIntosh, with additional items included to more accurately assess the four domains of suicide literacy identified by Calear et al. [16]. These domains are: a) signs and symptoms of suicide, b) causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, c) risk factors, and d) treatment and prevention of suicide. The psychometric properties of this questionnaire have been validated in various studies and have been effective in clinical studies and interventions [24]. By understanding the level of suicide literacy among individuals and exploring how this type of literacy impacts other psychological variables, we can gain a deeper understanding of this area and aid specialists and psychotherapists in suicide-related interventions. Additionally, this study is important as there is no existing tool in Persian to measure suicide literacy and evaluate it alongside other related variables.

Moreover, given that military personnel, especially soldiers, are prone to suicidal thoughts due to factors such as the pressures of the military environment, challenges with commanders, difficulty adapting to changes, and personality issues, it is necessary to investigate and measure the level of suicide literacy within this population. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to translate and assess the validity and reliability of the LOSS by Calear et al. in the military community.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study employed a methodological approach. The study population consisted of military personnel serving in the guard corps of Tehran and Arak during April and May 2021.

The sample was selected via convenience sampling and included 10 experts for the content validity assessment stage, 20 soldiers for the qualitative assessment of face validity, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), difficulty coefficient, and a test-retest assessment within a 2-week period, and 415 soldiers to assess the concurrent validity. Inclusion criteria were the absence of psychological disorders or any history of suicide and self-mutilation. Exclusion criteria included refusal to participate in the study and incomplete questionnaire responses.

Translation process

Initially, the English version of the questionnaire was translated into Farsi by experts in the English language. Subsequently, in the backward-forward stage, the Farsi translation was independently re-translated into English by two bilingual individuals. This version was then compared with the original, and the final version was prepared by the research team. The final Persian version of the questionnaire was approved after being reviewed by an expert in Persian language and literature.

Validation

Face validity

To evaluate face validity, the questionnaires were completed by 20 soldiers, and their validity was assessed using the Impact Score formula. The accepted standard for the item impact score was 1.5.

Content validity

Content validity was evaluated using the content validity ratio (CVR) according to Lawshe's table. With ten experts, a CVR above 0.62 was considered acceptable [25]. The content validity index (CVI) according to Waltz & Bausell was also used to measure content validity. According to this index, items scoring below 0.7 are rejected, those between 0.7 and 0.79 need revision, and those above 0.79 are acceptable [26].

To this end, questionnaires were initially sent to ten experts in health education, nursing, nutrition, and psychology to assess the necessity and importance of the questions. For questions with a CVI and CVR estimated to be less than 0.62 and 0.70 respectively, these questions were presented to the ten experts again in a second stage; six experts responded, and the CVI and CVR were recalculated.

Reliability

To assess reliability, the questionnaires were initially administered to 20 soldiers. After two weeks, the same participants were asked to fill out the questionnaires again. Subsequently, the intra-class correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the consistency of the responses over time.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was assessed by examining the relationship between the scores of the LOSS and the Stigma of Suicide Scale (SOSS), which measures convergent validity. The difficulty coefficient was also utilized in this study.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23 by Spearman’s rank correlation, and also we measured item difficulty and analyzed the scale reliability using Cronbach's alpha coefficient.

Tools

Literacy of Suicide Scale

The LOSS was developed by Calear et al. to measure the level of suicide literacy. This scale contains 27 items, 12 of which are taken from the Revised Facts on Suicide Quiz (RFOS) developed by Hubbard and McIntosh, with additional items added to more accurately assess the four domains of suicide literacy identified by Calear et al. [16]. These domains include: a) causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (questions 1 to 10), b) risk factors (questions 11 to 17), c) signs and symptoms of suicide (questions 18 to 23), and d) treatment and prevention of suicide (questions 24 to 27). In this questionnaire, correct answers are scored as 1, while incorrect answers and responses of "I don't know" receive a score of 0. The sum of the correct answers and the total score indicates an individual's literacy level. Higher scores reflect a higher level of suicide literacy. This scale is useful for identifying the strengths and weaknesses of individuals' awareness in the realm of suicide [16].

Stigma of Suicide Scale

This questionnaire, created by Batterham et al., is designed to evaluate the stigmatizing attitudes of the general public toward individuals who commit suicide. It comes in two versions: a long version with 58 questions and a short version with 16 questions. Each question is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), where higher scores indicate greater levels of stigmatization towards those who are suicidal [27]. The SOSS includes three subscales: Stigma, Isolation/Depression, and Glorification/Normalization. The first subscale, Stigma, has shown a Cronbach's alpha of 0.70 for narrative validity. The convergence validity of the total scale score was 0.66 according to Batterham et al., and the construct validity for the depression subscale was reported as 0.46 [27]. In a study by Chan et al. [28], Cronbach's alpha for the subscales of stigma, isolation/depression, and glorification/normalization were estimated to be 0.95, 0.90, and 0.88, respectively. Ozturk et al. reported an internal correlation of 0.93 for the Turkish version of this scale [29]. In the present study, this questionnaire was used to assess convergent validity.

Findings

Demographic information

First stage

In the initial stage, 30 soldiers were studied. All participants were single, from the city of Arak, served in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and had no history of self-harm, drug use, or psychiatric referrals. The mean age of the participants was 21.75±2.97 years, and the mean duration of military service was 20.55±3.72 months.

Second stage

To test concurrent validity, a questionnaire was administered to 415 soldiers. All participants were single, from the city of Arak, and served in the IRGC. The mean age of the participants was 21.40 ± 2.41 years. Among the participants, 72 had a low economic status (up to 118.5 dollars), 181 had a moderate economic status (118.5 to 237 dollars), and 162 had a high economic status (more than 237 dollars). The mean duration of military service was 20.55 months with a standard deviation of 3.72.

Translation process and content validity

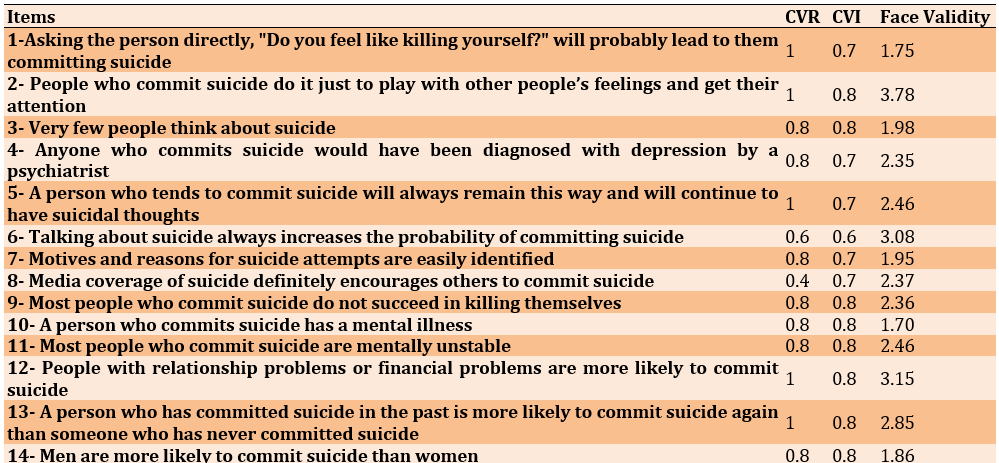

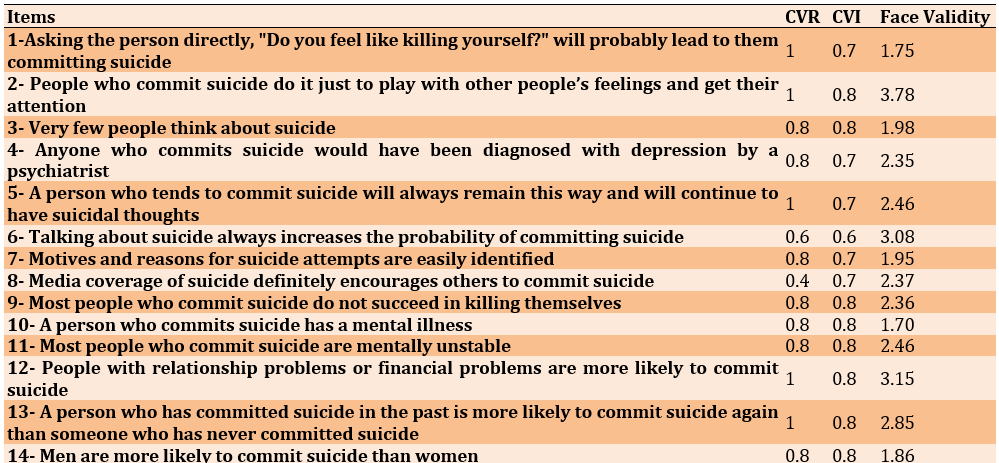

In the suicide literacy questionnaire, questions 1 ("Asking someone directly, 'Do you feel like committing suicide?' will probably lead to that person's suicide"), 8 ("Media coverage of suicide will definitely encourage others to commit suicide"), 22 ("Suicide rarely happens without warning"), and 23 ("The highest risk of suicide in depressed people is when they start to recover") were modified based on expert feedback. The removal of these questions was due to their CVR and CVI.

The face validity study results indicated that the CVR for questions 1, 2, 5, 12, 13, 17, 19, and 21 was 1; for questions 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, and 24 it was 0.8; for questions 6, 22, 23, 25, and 27 it was 0.6; and for questions 8 and 26 it was 0.4. The CVI for questions 2, 3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19 was also 0.8; for questions 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 20, 21, and 22 it was 0.7; for questions 6, 23, 24, and 25 it was 0.6; for question 26 it was 0.5; and for question 27 it was 0.4.

Based on the results obtained, the face validity of each question was reported as favorable (ranging from 1.39 to 3.78).

In the first stage, questionnaires were sent to 30 people, of whom 10 experts responded and their CVI and CVR were calculated. Based on the cutoff point of 0.62 for CVR and 0.70 for CVI, some questions scored below these thresholds. After recalculations, in the suicide literacy questionnaire, seven questions (6, 8, 22, 23, 25, 26, and 27) fell below the CVR cutoff point and six questions (6, 23, 24, 25, 26, and 27) fell below the CVI cutoff point. The rest of the questions were considered favorable.

In the second stage, these questions were once again sent to six experts. The results indicated that in the suicide literacy questionnaire, all the questions were retained, but nine questions were edited, modified, and considered to be fluently phrased (Table 1).

Table 1. The CVR, CVI and the face validity values of the Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS)

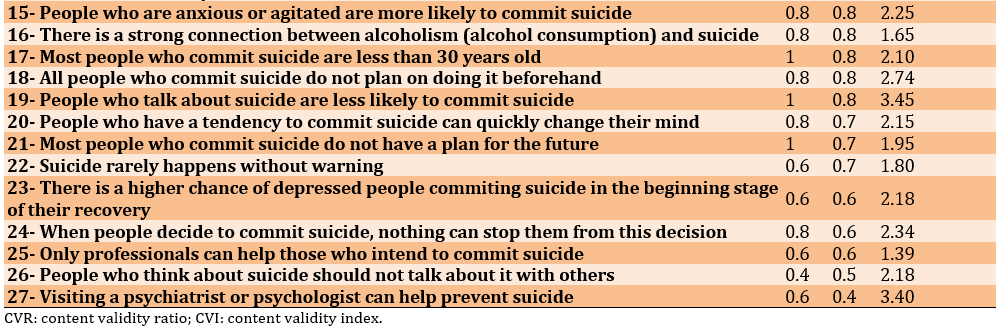

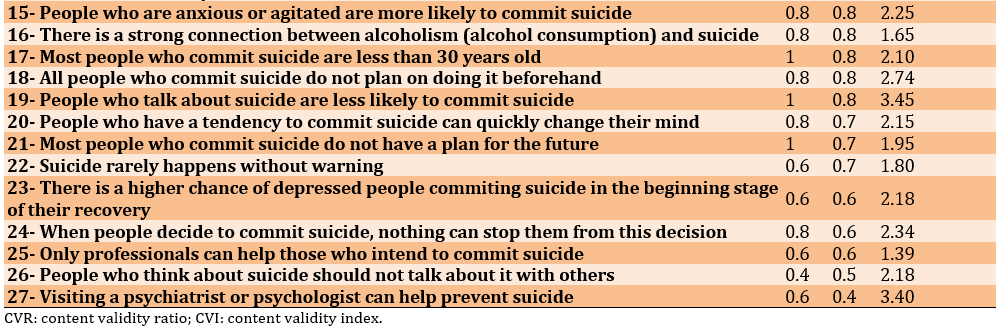

Reliability

The Cronbach's alpha for the components of the suicide literacy questionnaire was higher than 0.70, indicating good reliability. Additionally, the Kuder-Richardson and ICC values were also at a favorable level. According to experts, the difficulty level of the questions was deemed appropriate (Table 2).

Table 2. Measurement of the reliability of the Persian version of the Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS) (n=20)

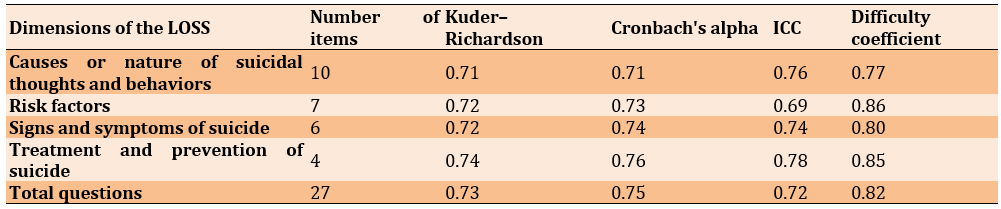

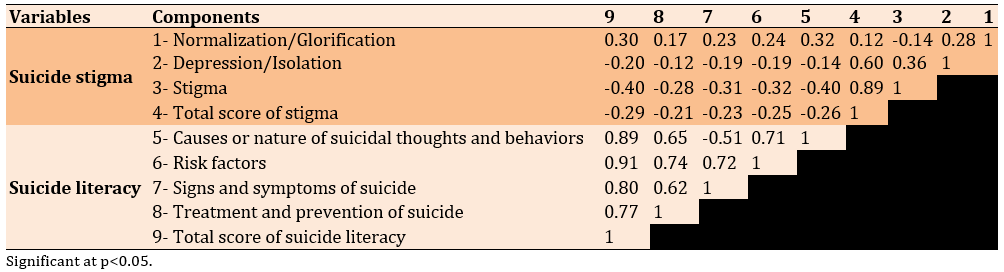

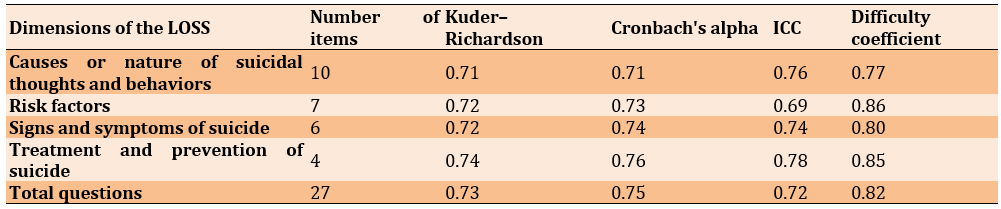

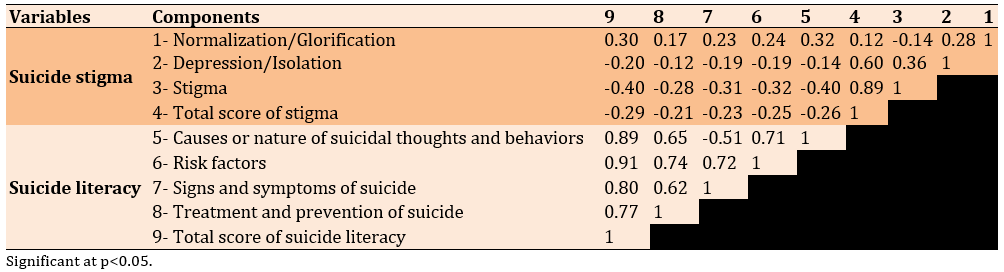

Convergent validity

In Table 3, the relationships between the components of the LOSS and the SOSS are explored.

Table 3. Correlation of the components of Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS) and Stigma of Suicide Scale (SOSS) (n=415)

As detailed in Table 3, the total score of suicide literacy shows a direct and significant relationship with the normalization components, causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, risk factors, signs and symptoms of suicide, and treatment and prevention of suicide. It also exhibits an indirect and significant relationship with the components of depression, stigma, and the total stigma score.

All components of suicide literacy—causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, risk factors, signs and symptoms of suicide, and treatment and prevention of suicide—demonstrate a direct and significant relationship with the total score of this questionnaire at both stages. Specifically, in the first stage, the components with the highest correlation with the total score were risk factors (r=0.702; p=0.01), causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (r=0.666; p=0.01), signs and symptoms of suicide (r=0.490; p=0.01), and treatment and prevention of suicide (r=0.358; p=0.01), respectively.

In the second stage, the components with the highest correlation were causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (r=0.768; p=0.01), risk factors (r=0.721; p=0.01), signs and symptoms of suicide (r=0.556; p=0.01), and treatment and prevention of suicide (r=0.432; p=0.01), respectively.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to psychometrically evaluate the LOSS within military forces. The statistical sample included two specialists and experts during the translation stage, 16 experts in the content validity evaluation stage, 20 soldiers for the qualitative evaluation of face validity, and 415 soldiers to assess convergent validity. The results indicated that based on the CVR, CVI, and face validity, all questions of the suicide literacy questionnaire were at the optimal level and all 27 questions were maintained and found to be culturally compatible. The CVI of our study was 0.7 and above, while the CVI of the Malay version of the LOSS (M-LOSS (I-CVI)) and the Turkish version was 0.83 (and above) and 0.8 (and above), respectively [30, 31]. Given that the population of our study was the military community, a unique demographic, the CVI results of this study justify and demonstrate the validity of the Persian version.

Additionally, Kuder-Richardson and optimal components were calculated. Al-Dalake et al. [32] concluded in their study that the LOSS has a favorable Cronbach's alpha (Cronbach's alpha>0.70). The Kuder-Richardson score in the Turkish version was 0.61, which was lower than in our study [31]. In a study on the general population of Iran, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.85 and the ICC was 0.89, both higher than in the present study [33]. A study in India on medical students reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74, similar to our findings. Thus, the reliability index of our study was moderate and favorable compared to other studies [23].

The results of Spearman's internal correlation coefficient showed that all components of suicide literacy had a direct and significant relationship with the total score of this questionnaire, and the subscales of LOSS had a positive and strong correlation with each other. However, there was a weak negative correlation between the subscales of the SOSS and LOSS. The significance, strength, and direction of the correlation were reported in the Arabic version [32]. The correlation of this questionnaire with the stigma questionnaire was reported as -0.50, indicating that the suicide literacy and suicide stigma questionnaires in Arab society have good validity and reliability. Similar to the present study, in the German population, LOSS was negatively associated with SOSS [34]. Gholamrezaei et al. found a significant relationship between suicide literacy and suicide stigma at the 0.05 level [21]. In line with these results, Claire et al. [24] concluded that this questionnaire has good validity and reliability and can be used for psychological education interventions. Consequently, LOSS demonstrated good convergent validity with the SOSS.

According to the obtained and previous results, it can be said that the increase in suicide literacy in people causes the attitude of people and the way they deal with suicide to change in a positive way, and this understanding and knowledge, both for them and for the people who commit suicide, can be fruitful. As a result, the availability of suitable tools for evaluating the level of suicide literacy can be very useful in assessing the level of awareness and literacy in individuals, provinces of the country, different cultures, military personnel, etc. Accreditation and localization of such a tool assist in understanding the prevalence, rate and severity of suicide in the country (and especially among the military) and in taking appropriate measures to prevent and reduce it. Compared with other researches, the obtained results have good validity and vision. As a result, according to the results of this research and other researches, it can be concluded that this questionnaire can be used in Iranian society.

Given the increasing statistics of suicide in Iran, the taboo nature of the subject in society, and the general public's lack of awareness about the causes and consequences of suicide, coupled with insufficient research in this area, this study proves to be valuable. By understanding the level of suicide literacy among the population and exploring how this type of literacy affects other psychological variables, we can gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding in this field. This knowledge assists specialists and psychotherapists in developing interventions related to suicide prevention and management.

Among the limitations of this research are the lack of confidence in the study by individuals with a history of suicide, the fact that the research was conducted only on soldiers, the absence of samples from different ethnicities and cultures, and the incomplete filling out of a number of questionnaires by the soldiers (due to fatigue and lack of time). This resulted in some questionnaires being discarded and replaced with others. Additionally, because the items are binary-coded (correct or incorrect), factor structure analysis was not conducted on the LOSS. Nevertheless, this is the first time such research has been conducted within the military community in Iran. The convenience sampling method also limits the generalizability of the results.

We recommend enhancing the suicide literacy of soldiers through various classes and workshops, teaching them concepts related to suicide. Furthermore, following the completion of the psychometric evaluation, we recommend using the current questionnaire to assess the level of suicide literacy in the general population.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the LOSS within the soldier community demonstrates good and favorable validity and reliability, making it suitable for measuring the level of suicide literacy in this group.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank all the soldiers who participated in this study and Kosar Jafari for editing this paper. We are also grateful to the Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah Hospital for their cooperation.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical considerations were duly observed in this study. Necessary permits for this study were obtained from the relevant research center. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their recorded information. This study has been registered with the ethics code IR.BMSU.REC.1400.097 at Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Zohrehvand M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (30%); Rahmati F (Second Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer (30%); Saffari M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Dowran B (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: There is nothing to be declared.

Suicide is a significant public health issue [1] and ranks among the leading causes of death globally [2]. It is also one of the top ten causes of death and lost years of life in many parts of the world [3]. The term "suicide" refers to death caused by self-inflicted injury with the intent to die [4].

The World Health Organization has identified suicide as a public health priority, stating that suicide prevention is essential in all countries. Key underlying factors of suicide include predisposing physical diseases, mental disorders, demographic factors, economic factors, environmental factors, issues related to refuge and immigration, emotional-communication problems, incarceration, and family issues [5, 6].

Every year, approximately 700,000 individuals die from suicide worldwide. Suicide can occur at any point throughout the life cycle and stands as the fourth leading cause of death among individuals aged 15-29 years globally [7]. Common methods of suicide include the use of firearms, hanging, suffocation, drowning, carbon monoxide poisoning, jumping, and drug overdose. The incidence of suicide has been rising gradually worldwide, particularly in European countries. For example, in the Netherlands, the number of suicides increases annually by between 3% and 6% [8].

Suicide rates are also increasing in Iran. A meta-analysis concluded that in recent decades, Iran has seen the largest increase in suicide rates among Islamic and Eastern Mediterranean countries [9]. The provinces of Ilam, Lorestan, Hamadan, Kurdistan, and Kermanshah have the highest rates of completed suicides, while the provinces of Isfahan, Yazd, Semnan, and Qom have the highest rates of attempted suicide and the lowest rates of completed suicide [10]. Furthermore, findings from Zarani and Ahmadi's study indicate that contrary to global statistics, suicide attempts are more prevalent among Iranian men [11].

Suicidal behavior is categorized into four main types: suicidal thoughts, planning, attempts, and completed suicide. Suicidal ideation involves harboring thoughts and plans for suicide without necessarily acting on them. In the planning stage, an individual makes preparations by securing the means or location for suicide [12].

Suicide can also occur among soldiers. In a survey, the suicide rate for military personnel was reported as twelve per 100,000 people, compared to nine per 100,000 among civilians [13]. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has reported that 17 veterans die by suicide every day. Consistent with this, studies have estimated that suicide is more common among military personnel than civilians [14, 15].

Furthermore, suicide literacy is crucial both in the general population and particularly among military personnel. Suicide literacy refers to the understanding of the causes, risk factors, signs, symptoms, and treatments of suicide. This knowledge is vital as it can help reduce the prevalence of suicide by encouraging individuals to seek professional help. In contrast, incorrect or incomplete knowledge may cause hesitance in seeking the necessary support for suicide prevention [16]. Generally, suicide literacy is insufficient [17], leading to the stigmatization of suicide as a taboo topic and the neglect of its warning signs [18].

Studies have shown that the quality of nursing care for patients who have attempted suicide can be influenced by various factors, including the nurses' knowledge about suicide, their ability to assess suicide risk, and their professional experiences, attitudes, and beliefs about suicide as a taboo subject [19]. Additional research also confirms that suicide literacy effectively improves attitudes, reduces stigmatization, and decreases judgment toward affected individuals [20-23].

As a result, it is crucial to identify groups with limited literacy in this field to promote mental health programs. By enhancing public and professional awareness about suicide, we can better manage and prevent it. One tool that can be used to evaluate the level of suicide literacy is a questionnaire. The Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS) by Calear et al. is a suitable tool for this purpose [16]. This scale is valuable and practical due to its reference scale and the absence of a similar questionnaire in Iran. The LOSS contains 27 items; twelve items are taken from the Revised Facts on Suicide Quiz (RFOS) developed by Hubbard and McIntosh, with additional items included to more accurately assess the four domains of suicide literacy identified by Calear et al. [16]. These domains are: a) signs and symptoms of suicide, b) causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, c) risk factors, and d) treatment and prevention of suicide. The psychometric properties of this questionnaire have been validated in various studies and have been effective in clinical studies and interventions [24]. By understanding the level of suicide literacy among individuals and exploring how this type of literacy impacts other psychological variables, we can gain a deeper understanding of this area and aid specialists and psychotherapists in suicide-related interventions. Additionally, this study is important as there is no existing tool in Persian to measure suicide literacy and evaluate it alongside other related variables.

Moreover, given that military personnel, especially soldiers, are prone to suicidal thoughts due to factors such as the pressures of the military environment, challenges with commanders, difficulty adapting to changes, and personality issues, it is necessary to investigate and measure the level of suicide literacy within this population. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to translate and assess the validity and reliability of the LOSS by Calear et al. in the military community.

Instrument and Methods

This cross-sectional study employed a methodological approach. The study population consisted of military personnel serving in the guard corps of Tehran and Arak during April and May 2021.

The sample was selected via convenience sampling and included 10 experts for the content validity assessment stage, 20 soldiers for the qualitative assessment of face validity, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), difficulty coefficient, and a test-retest assessment within a 2-week period, and 415 soldiers to assess the concurrent validity. Inclusion criteria were the absence of psychological disorders or any history of suicide and self-mutilation. Exclusion criteria included refusal to participate in the study and incomplete questionnaire responses.

Translation process

Initially, the English version of the questionnaire was translated into Farsi by experts in the English language. Subsequently, in the backward-forward stage, the Farsi translation was independently re-translated into English by two bilingual individuals. This version was then compared with the original, and the final version was prepared by the research team. The final Persian version of the questionnaire was approved after being reviewed by an expert in Persian language and literature.

Validation

Face validity

To evaluate face validity, the questionnaires were completed by 20 soldiers, and their validity was assessed using the Impact Score formula. The accepted standard for the item impact score was 1.5.

Content validity

Content validity was evaluated using the content validity ratio (CVR) according to Lawshe's table. With ten experts, a CVR above 0.62 was considered acceptable [25]. The content validity index (CVI) according to Waltz & Bausell was also used to measure content validity. According to this index, items scoring below 0.7 are rejected, those between 0.7 and 0.79 need revision, and those above 0.79 are acceptable [26].

To this end, questionnaires were initially sent to ten experts in health education, nursing, nutrition, and psychology to assess the necessity and importance of the questions. For questions with a CVI and CVR estimated to be less than 0.62 and 0.70 respectively, these questions were presented to the ten experts again in a second stage; six experts responded, and the CVI and CVR were recalculated.

Reliability

To assess reliability, the questionnaires were initially administered to 20 soldiers. After two weeks, the same participants were asked to fill out the questionnaires again. Subsequently, the intra-class correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the consistency of the responses over time.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was assessed by examining the relationship between the scores of the LOSS and the Stigma of Suicide Scale (SOSS), which measures convergent validity. The difficulty coefficient was also utilized in this study.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23 by Spearman’s rank correlation, and also we measured item difficulty and analyzed the scale reliability using Cronbach's alpha coefficient.

Tools

Literacy of Suicide Scale

The LOSS was developed by Calear et al. to measure the level of suicide literacy. This scale contains 27 items, 12 of which are taken from the Revised Facts on Suicide Quiz (RFOS) developed by Hubbard and McIntosh, with additional items added to more accurately assess the four domains of suicide literacy identified by Calear et al. [16]. These domains include: a) causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (questions 1 to 10), b) risk factors (questions 11 to 17), c) signs and symptoms of suicide (questions 18 to 23), and d) treatment and prevention of suicide (questions 24 to 27). In this questionnaire, correct answers are scored as 1, while incorrect answers and responses of "I don't know" receive a score of 0. The sum of the correct answers and the total score indicates an individual's literacy level. Higher scores reflect a higher level of suicide literacy. This scale is useful for identifying the strengths and weaknesses of individuals' awareness in the realm of suicide [16].

Stigma of Suicide Scale

This questionnaire, created by Batterham et al., is designed to evaluate the stigmatizing attitudes of the general public toward individuals who commit suicide. It comes in two versions: a long version with 58 questions and a short version with 16 questions. Each question is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), where higher scores indicate greater levels of stigmatization towards those who are suicidal [27]. The SOSS includes three subscales: Stigma, Isolation/Depression, and Glorification/Normalization. The first subscale, Stigma, has shown a Cronbach's alpha of 0.70 for narrative validity. The convergence validity of the total scale score was 0.66 according to Batterham et al., and the construct validity for the depression subscale was reported as 0.46 [27]. In a study by Chan et al. [28], Cronbach's alpha for the subscales of stigma, isolation/depression, and glorification/normalization were estimated to be 0.95, 0.90, and 0.88, respectively. Ozturk et al. reported an internal correlation of 0.93 for the Turkish version of this scale [29]. In the present study, this questionnaire was used to assess convergent validity.

Findings

Demographic information

First stage

In the initial stage, 30 soldiers were studied. All participants were single, from the city of Arak, served in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and had no history of self-harm, drug use, or psychiatric referrals. The mean age of the participants was 21.75±2.97 years, and the mean duration of military service was 20.55±3.72 months.

Second stage

To test concurrent validity, a questionnaire was administered to 415 soldiers. All participants were single, from the city of Arak, and served in the IRGC. The mean age of the participants was 21.40 ± 2.41 years. Among the participants, 72 had a low economic status (up to 118.5 dollars), 181 had a moderate economic status (118.5 to 237 dollars), and 162 had a high economic status (more than 237 dollars). The mean duration of military service was 20.55 months with a standard deviation of 3.72.

Translation process and content validity

In the suicide literacy questionnaire, questions 1 ("Asking someone directly, 'Do you feel like committing suicide?' will probably lead to that person's suicide"), 8 ("Media coverage of suicide will definitely encourage others to commit suicide"), 22 ("Suicide rarely happens without warning"), and 23 ("The highest risk of suicide in depressed people is when they start to recover") were modified based on expert feedback. The removal of these questions was due to their CVR and CVI.

The face validity study results indicated that the CVR for questions 1, 2, 5, 12, 13, 17, 19, and 21 was 1; for questions 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, and 24 it was 0.8; for questions 6, 22, 23, 25, and 27 it was 0.6; and for questions 8 and 26 it was 0.4. The CVI for questions 2, 3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19 was also 0.8; for questions 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 20, 21, and 22 it was 0.7; for questions 6, 23, 24, and 25 it was 0.6; for question 26 it was 0.5; and for question 27 it was 0.4.

Based on the results obtained, the face validity of each question was reported as favorable (ranging from 1.39 to 3.78).

In the first stage, questionnaires were sent to 30 people, of whom 10 experts responded and their CVI and CVR were calculated. Based on the cutoff point of 0.62 for CVR and 0.70 for CVI, some questions scored below these thresholds. After recalculations, in the suicide literacy questionnaire, seven questions (6, 8, 22, 23, 25, 26, and 27) fell below the CVR cutoff point and six questions (6, 23, 24, 25, 26, and 27) fell below the CVI cutoff point. The rest of the questions were considered favorable.

In the second stage, these questions were once again sent to six experts. The results indicated that in the suicide literacy questionnaire, all the questions were retained, but nine questions were edited, modified, and considered to be fluently phrased (Table 1).

Table 1. The CVR, CVI and the face validity values of the Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS)

Reliability

The Cronbach's alpha for the components of the suicide literacy questionnaire was higher than 0.70, indicating good reliability. Additionally, the Kuder-Richardson and ICC values were also at a favorable level. According to experts, the difficulty level of the questions was deemed appropriate (Table 2).

Table 2. Measurement of the reliability of the Persian version of the Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS) (n=20)

Convergent validity

In Table 3, the relationships between the components of the LOSS and the SOSS are explored.

Table 3. Correlation of the components of Literacy of Suicide Scale (LOSS) and Stigma of Suicide Scale (SOSS) (n=415)

As detailed in Table 3, the total score of suicide literacy shows a direct and significant relationship with the normalization components, causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, risk factors, signs and symptoms of suicide, and treatment and prevention of suicide. It also exhibits an indirect and significant relationship with the components of depression, stigma, and the total stigma score.

All components of suicide literacy—causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, risk factors, signs and symptoms of suicide, and treatment and prevention of suicide—demonstrate a direct and significant relationship with the total score of this questionnaire at both stages. Specifically, in the first stage, the components with the highest correlation with the total score were risk factors (r=0.702; p=0.01), causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (r=0.666; p=0.01), signs and symptoms of suicide (r=0.490; p=0.01), and treatment and prevention of suicide (r=0.358; p=0.01), respectively.

In the second stage, the components with the highest correlation were causes or nature of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (r=0.768; p=0.01), risk factors (r=0.721; p=0.01), signs and symptoms of suicide (r=0.556; p=0.01), and treatment and prevention of suicide (r=0.432; p=0.01), respectively.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to psychometrically evaluate the LOSS within military forces. The statistical sample included two specialists and experts during the translation stage, 16 experts in the content validity evaluation stage, 20 soldiers for the qualitative evaluation of face validity, and 415 soldiers to assess convergent validity. The results indicated that based on the CVR, CVI, and face validity, all questions of the suicide literacy questionnaire were at the optimal level and all 27 questions were maintained and found to be culturally compatible. The CVI of our study was 0.7 and above, while the CVI of the Malay version of the LOSS (M-LOSS (I-CVI)) and the Turkish version was 0.83 (and above) and 0.8 (and above), respectively [30, 31]. Given that the population of our study was the military community, a unique demographic, the CVI results of this study justify and demonstrate the validity of the Persian version.

Additionally, Kuder-Richardson and optimal components were calculated. Al-Dalake et al. [32] concluded in their study that the LOSS has a favorable Cronbach's alpha (Cronbach's alpha>0.70). The Kuder-Richardson score in the Turkish version was 0.61, which was lower than in our study [31]. In a study on the general population of Iran, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.85 and the ICC was 0.89, both higher than in the present study [33]. A study in India on medical students reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74, similar to our findings. Thus, the reliability index of our study was moderate and favorable compared to other studies [23].

The results of Spearman's internal correlation coefficient showed that all components of suicide literacy had a direct and significant relationship with the total score of this questionnaire, and the subscales of LOSS had a positive and strong correlation with each other. However, there was a weak negative correlation between the subscales of the SOSS and LOSS. The significance, strength, and direction of the correlation were reported in the Arabic version [32]. The correlation of this questionnaire with the stigma questionnaire was reported as -0.50, indicating that the suicide literacy and suicide stigma questionnaires in Arab society have good validity and reliability. Similar to the present study, in the German population, LOSS was negatively associated with SOSS [34]. Gholamrezaei et al. found a significant relationship between suicide literacy and suicide stigma at the 0.05 level [21]. In line with these results, Claire et al. [24] concluded that this questionnaire has good validity and reliability and can be used for psychological education interventions. Consequently, LOSS demonstrated good convergent validity with the SOSS.

According to the obtained and previous results, it can be said that the increase in suicide literacy in people causes the attitude of people and the way they deal with suicide to change in a positive way, and this understanding and knowledge, both for them and for the people who commit suicide, can be fruitful. As a result, the availability of suitable tools for evaluating the level of suicide literacy can be very useful in assessing the level of awareness and literacy in individuals, provinces of the country, different cultures, military personnel, etc. Accreditation and localization of such a tool assist in understanding the prevalence, rate and severity of suicide in the country (and especially among the military) and in taking appropriate measures to prevent and reduce it. Compared with other researches, the obtained results have good validity and vision. As a result, according to the results of this research and other researches, it can be concluded that this questionnaire can be used in Iranian society.

Given the increasing statistics of suicide in Iran, the taboo nature of the subject in society, and the general public's lack of awareness about the causes and consequences of suicide, coupled with insufficient research in this area, this study proves to be valuable. By understanding the level of suicide literacy among the population and exploring how this type of literacy affects other psychological variables, we can gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding in this field. This knowledge assists specialists and psychotherapists in developing interventions related to suicide prevention and management.

Among the limitations of this research are the lack of confidence in the study by individuals with a history of suicide, the fact that the research was conducted only on soldiers, the absence of samples from different ethnicities and cultures, and the incomplete filling out of a number of questionnaires by the soldiers (due to fatigue and lack of time). This resulted in some questionnaires being discarded and replaced with others. Additionally, because the items are binary-coded (correct or incorrect), factor structure analysis was not conducted on the LOSS. Nevertheless, this is the first time such research has been conducted within the military community in Iran. The convenience sampling method also limits the generalizability of the results.

We recommend enhancing the suicide literacy of soldiers through various classes and workshops, teaching them concepts related to suicide. Furthermore, following the completion of the psychometric evaluation, we recommend using the current questionnaire to assess the level of suicide literacy in the general population.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the LOSS within the soldier community demonstrates good and favorable validity and reliability, making it suitable for measuring the level of suicide literacy in this group.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank all the soldiers who participated in this study and Kosar Jafari for editing this paper. We are also grateful to the Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah Hospital for their cooperation.

Ethical Permissions: Ethical considerations were duly observed in this study. Necessary permits for this study were obtained from the relevant research center. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their recorded information. This study has been registered with the ethics code IR.BMSU.REC.1400.097 at Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contribution: Zohrehvand M (First Author), Introduction Writer/Main Researcher (30%); Rahmati F (Second Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer (30%); Saffari M (Third Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (20%); Dowran B (Fourth Author), Assistant Researcher/ Statistical Analyst (20%)

Funding/Support: There is nothing to be declared.

Keywords:

References

1. Boyd MA. Psychiatric nursing: Contemporary practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Link]

2. Mullins N, Kang J, Campos AI, Coleman JR, Edwards AC, Galfalvy H, et al. Dissecting the shared genetic architecture of suicide attempt, psychiatric disorders, and known risk factors. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91(3):313-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.05.029]

3. Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ. 2019;364:194. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmj.l94]

4. Hawton K, Van Heeringen K. Future perspectives. In: The international handbook on suicide and attempted suicide. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. p. 713-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/9780470698976.ch41]

5. Mohammadkhani P, Khanipour H, Jafari F, Mobarram A. Predictors of suicide in male prisoners with substance abuse and dependence: Protective factors and risk factors. Iran J forensic med. 2013;19(4 and 1):205-14. [Persian] [Link]

6. Shakeri A, Jafari Zadeh F. The reasons for successful suicides in Fars province. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2013;22(97):271-5. [Persian] [Link]

7. Lovero KL, Dos Santos PF, Come AX, Wainberg ML, Oquendo MA. Suicide in Global Mental Health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25(6):255-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11920-023-01423-x]

8. Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, Van Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):646-59. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X]

9. Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Zamani N. Suicide in Iran: The facts and the figures from nationwide reports. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(1):73-7. [Link]

10. Daliri S, Bazyar J, Sayehmiri K, Delpisheh A, Sayehmiri F. The incidence rates of suicide attempts and successful suicides in seven climatic conditions in Iran from 2001 to 2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2017;21(6):1-15. [Persian] [Link]

11. Zarani F, Ahmadi Z. Suicide in Iranian culture: A systematic review study. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi J. 2021;10(9):205-16. [Persian] [Link]

12. Bakhtar M, Rezaeian M. The prevalence of suicide thoughts and attempted suicide plus their risk factors among Iranian students: A systematic review study. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2017;15(11):1061-76. [Persian] [Link]

13. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences clinical psychiatry. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins Co; 1988. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/00004850-198904000-00007]

14. Anisi J, Fathi Ashtiani A, Soltani Nejad A, Amiri M. Prevalence of suicidal ideation in soldiers and its associated factors. J Mil Med. 2006;8(2):113-8. [Persian] [Link]

15. Lineberry TW, O'Connor SS. Suicide in the US army. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(9):871-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.002]

16. Calear A, Batterham PJ, Christensen H. The literacy of suicide scale: Psychometric properties and correlates of suicide literacy. Unpublished manuscript; 2012. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/t19723-000]

17. Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(5):396-401. [Link] [DOI:10.1192/bjp.177.5.396]

18. Medina CO, Kullgren G, Dahlblom K. A qualitative study on primary health care professionals' perceptions of mental health, suicidal problems and help-seeking among young people in Nicaragua. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:129. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2296-15-129]

19. Jones S, Krishna M, Rajendra RG, Keenan P. Nurses attitudes and beliefs to attempted suicide in Southern India. J Ment Health. 2015;24(6):423-9. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/09638237.2015.1019051]

20. Ferlatte O, Salway T, Oliffe JL, Rice SM, Gilbert M, Young I, et al. Depression and suicide literacy among Canadian sexual and gender minorities. Arch Suicide Res. 2021;25(4):876-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13811118.2020.1769783]

21. Gholamrezaei A, Rezapour-Nasrabad R, Ghalenoei M, Nasiri M. Correlation between suicide literacy and stigmatizing attitude of nurses toward patients with suicide attempts. Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertension. 2019;14(3):351-5. [Spanish] [Link]

22. Li A, Huang X, Jiao D, O'Dea B, Zhu T, Christensen H. An analysis of stigma and suicide literacy in responses to suicides broadcast on social media. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2018;10(1):e12314. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/appy.12314]

23. Ram D, Chandran S. Suicide and depression literacy among health professions' students in tertiary care centre in South India. J Mood Disord. 2017;7(3):149-55. [Link] [DOI:10.5455/jmood.20170830064910]

24. Calear AL, Batterham PJ, Trias A, Christensen H. The literacy of suicide scale: Development, validation, and application. Crisis. 2021;43(5):385-90. [Link] [DOI:10.1027/0227-5910/a000798]

25. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers psychol. 1975;28(4):563-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x]

26. Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: Design, statistics, and computer analysis. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 1981. [Link]

27. Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Christensen H. The stigma of suicide scale: Psychometric properties and correlates of the stigma of suicide. Crisis. 2013;34(1):13-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1027/0227-5910/a000156]

28. Chan WI, Batterham P, Christensen H, Galletly C. Suicide literacy, suicide stigma and help-seeking intentions in Australian medical students. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(2):132-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1039856214522528]

29. Öztürk A, Akın S, Durna Z. Testing the psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the stigma of suicide scale (SOSS) with a sample of university students. J Psychiatric Nurs. 2017;8(2):102-9. [Link] [DOI:10.14744/phd.2017.38981]

30. Phoa PKA, Razak AA, Kuay HS, Ghazali AK, Rahman AA, Husain M, et al. The Malay literacy of suicide scale: A Rasch model validation and its correlation with mental health literacy among Malaysian parents, caregivers and teachers. Healthcare. 2022;10(7):1304. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/healthcare10071304]

31. Öztürk A, Akın S. The Turkish version of literacy of suicide scale (LOSS): Validity and reliability on a sample of Turkish university students. Int J Psychiatry Psychol Res. 2016;(7):20-42. [Link] [DOI:10.17360/UHPPD.2016723150]

32. Aldalaykeh M, Dalky H, Shahrour G, Rababa M. Psychometric properties of two Arabic Suicide Scales: Stigma and literacy. Heliyon. 2020;6(4):e03877. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03877]

33. Jafari A, Moshki M, Mokhtari AM, Ghaffari A, Nejatian M. Title page: Psychometric properties of literacy of suicide scale (LOSS) in Iranian population: Long form. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:608. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12889-023-15528-8]

34. Ludwig J, Dreier M, Liebherz S, Härter M, Von Dem Knesebeck O. Suicide literacy and suicide stigma-Results of a population survey from Germany. J Ment Health. 2022;31(4):517-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09638237.2021.1875421]