Volume 15, Issue 1 (2023)

Iran J War Public Health 2023, 15(1): 83-91 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2022/11/13 | Accepted: 2023/03/14 | Published: 2023/03/19

Received: 2022/11/13 | Accepted: 2023/03/14 | Published: 2023/03/19

How to cite this article

Alizadeh A, Javanmard Y, Dowran B, Azizi M, Salimi S. Causes and Consequences of Psychological Distress among Military Personnel. Iran J War Public Health 2023; 15 (1) :83-91

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1256-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1256-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Education and Research, Army Center of Excellence (NEZAJA), Center of Consultation of Khanevadeh Hospital, Tehran, Iran

2- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Health in Disaster and Emergencies, Faculty of Nursing, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- “Sport and Physiology Research Center” and “Clinical Psychology Department, Faculty of Medicine”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Health in Disaster and Emergencies, Faculty of Nursing, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- “Sport and Physiology Research Center” and “Clinical Psychology Department, Faculty of Medicine”, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (741 Views)

Introduction

High-risk occupations have remarkable levels of psychological and physical stress [1]. Encountering potentially traumatic events are common in the occupations of these people as a part of their job [2], and research has demonstrated the connection between passing such events and mental health problems among military staff members, police, as well as rescue and recovery workers [3].

While the military is defending the borders of the countries, it is also responsible for helping relief organizations when natural disasters and unexpected events occur. Hence, to constantly be well prepared and perfectly healthy is necessary. Instead, the Armed Forces’ nature and missions are so special that their related organization is continually dynamic and efficient. Therefore, their organization is more likely to change than others, which brings inconsistency and stress [4]. Certainly, mental health problem rates have broadly been analyzed in the military, particularly among troops on combat deployments [3].

Psychological Distress (PD) is an unfavorable emotional state which has physical and emotional manifestations and can consider an indicator of psychological problems examined in studies and clinical collections with psychological, social, and behavioral symptoms which are connected to anxiety and depression [2, 5]. PD can be considered as an emotional suffering that poses a real or perceived physical or psychological threat to an individual. A person's emotional challenges and psychological reactions to fit into the environment are defined by PD as a key indicator that negatively influences the occupational capacity of a person, his/her family life, and well-being [6].

Psychophysiological and behavioral symptoms that are not specific to a given mental pathology illustrate PD, which is a mental health consequence. Symptoms such as anxiety, depressive responses, irritability, descending intellectual capacity, fatigue, sleepiness, etc., and PD seem to be prevented by conditions of a work organization related to skill application, decision authority, social support in the workplace, and satisfaction while psychological, physical and contractual needs usually increase it [7, 8].

Military jobs are constantly faced with psychological distress and physical pressures such as lack of sleep, recreation, high monotony of the environment, and ceremonial and repetitive tasks. High job stress, low autonomy, and long working hours are other stressors of a military work environment. Some military personnel are constantly and intensely lonely and do not have the opportunity to receive assistance. These demands can lead to adjustment difficulties that manifest themselves in the form of distress and psychological disorders, and even suicide attempts [9]. Research has demonstrated the connection between traumatic, unpredictable events [3], and also rapid changes [4] with PD in the military.

The psychological distress of military jobs has major and dramatic consequences in the family and organizational environment. Weakening of individual and group performance, low accuracy at work, emotional problems, alcohol and drug abuse, misplaced violence, lack of cooperation and partnership with the commander, withdrawal from operational areas, divorce and marital and moral problems, and difficulty in decision-making are the consequences of PD in military personnel [10].

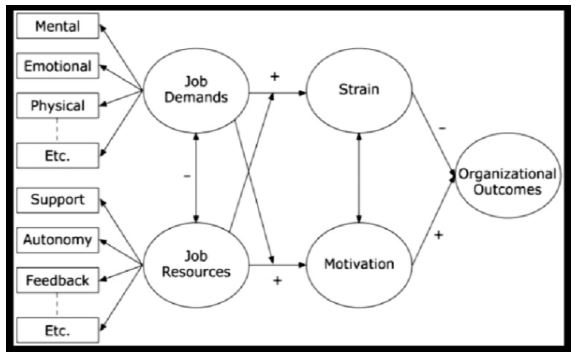

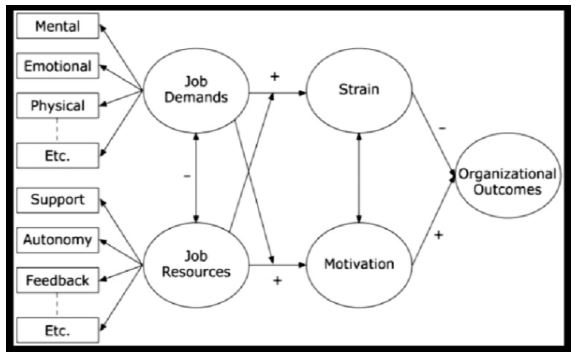

Military occupations in which personnel face high demands from the unit lead to greater psychological distress. The Job Demand-Resource Model (JD-R) classifies the factors affecting employee well-being into two different categories: job demands and job resources. Job demand includes those factors (such as time pressure and workload) that reduce health and energy and cause severe mental disorders over some time and ultimately, poor employee performance. In contrast, job resources include a variety of factors (such as management support, supervisor feedback, skills, and independence) that motivate employees and reduce the negative consequences of the job. In this model, two paths are identified: the destructive path of health and the path of motivation. In the destructive path of health, increasing demands and reducing resources can harm a person's health and have negative consequences such as burnout. While on the motivational path, increasing resources (rather than just reducing demand) can lead to increased employees' motivation and thus, better organizational performance (Figure 1) [11].

Figure 1) The job demand resource model [11]

Surprisingly, in our search, we did not find a study that comprehensively examines the factors influencing employees' psychological distress. Therefore, it is necessary to examine this concept in military personnel in depth without labeling it as a disorder and fear of stigma. In addition, especially this research type among the Iranian military personnel had a weak background in studies. Hence, there was a need for a better understanding of military psychological distress. We aimed to address the causes and patterns of PD in military personnel in detail and fundamentally. Thus, in examining this concept, the question arose in the research literature and the views of military personnel: “What factors contributed to the occurrence of psychological distress?” Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the factors that caused PD in Iranian military staff members.

Participants and Methods

Study design

This study is a qualitative research, which was done in two steps on PD among military personnel. The first stage was a brief review. We studied texts related to the factors influencing "PD in the military" in ScienceDirect, PubMed, Medline, IranDoc, SID, Ovid, ProQuest, IranMedex and Google Scholar, and other related texts from 2010 to 2020. The keywords PD, depression, anxiety, and anger with the keywords military, armed forces, soldier, and family were searched. Then we carefully read the found articles and texts. Moreover, we extracted the factors affecting PD from the texts. The second stage was the stage of interviewing experts including interviews with military psychologists. The researchers performed an in-depth direct analysis of the military experiences. The results were presented as codes, subcategories, and categories using an inductive approach. Finally, the results were organized into the framework of the JD-R model.

The statistical population of the first stage was all studies in the research literature related to the PD of the military. For the second stage, Participants were selected through the purposive sampling method from several universities. Selection of samples was based on the objective of the study. Research samples included groups of military personnel and military psychologists. Interviews with personnel were done at their workplaces. The endpoint for sample selection was reaching data saturation. Data collection and analysis for this study were done from October 10th, 2019 to April 16th, 2020, through in-depth semi-structured interviews with the participants. Interviews with participants began with an explanation of the psychological distress concept, and according to the interview guidelines, general open-ended questions were asked, “In your opinion, what factors cause psychological distress in military personnel?” Or “What factors cause discomfort and anxiety in military personnel?” Then, depending on the context of the responses, the interviewer continued with exploratory questions, “Can you please give an example?” or “Could you explain more?” to clarify concepts for the researcher and participants. The interview duration ranged between 45 and 60 minutes, depending on the willingness and situation of the respondent. Finally, by adding this question, “Would you like to add anything else?” the possibility of having experiences or cases beyond the author's imagination was examined.

After each interview, verbatim transcriptions were prepared using MAXQDA 10. Each entire interview was considered as an analysis unit. The transcribed script was read several times to become familiar with the context. Then, the meaning units were identified. After that, the condensed meaning units were abstracted and labeled with a code, and compared based on differences and similarities, and sorted into sub-categories and categories. Finally, the results were organized into the framework of the JD-R model.

Trustworthiness of data

Several strategies were used to ensure the credibility of the data. In this regard, data gathering lasted about one month, and the researchers were deeply oriented to data and the atmosphere of the field during this time. Some strategies were used to ensure the credibility of the data, including peer review (data and their interpretations were checked by other researchers) and member checking (data were rechecked by participants and, our interpretations from data were reviewed and confirmed by them).

Findings

Stage 1

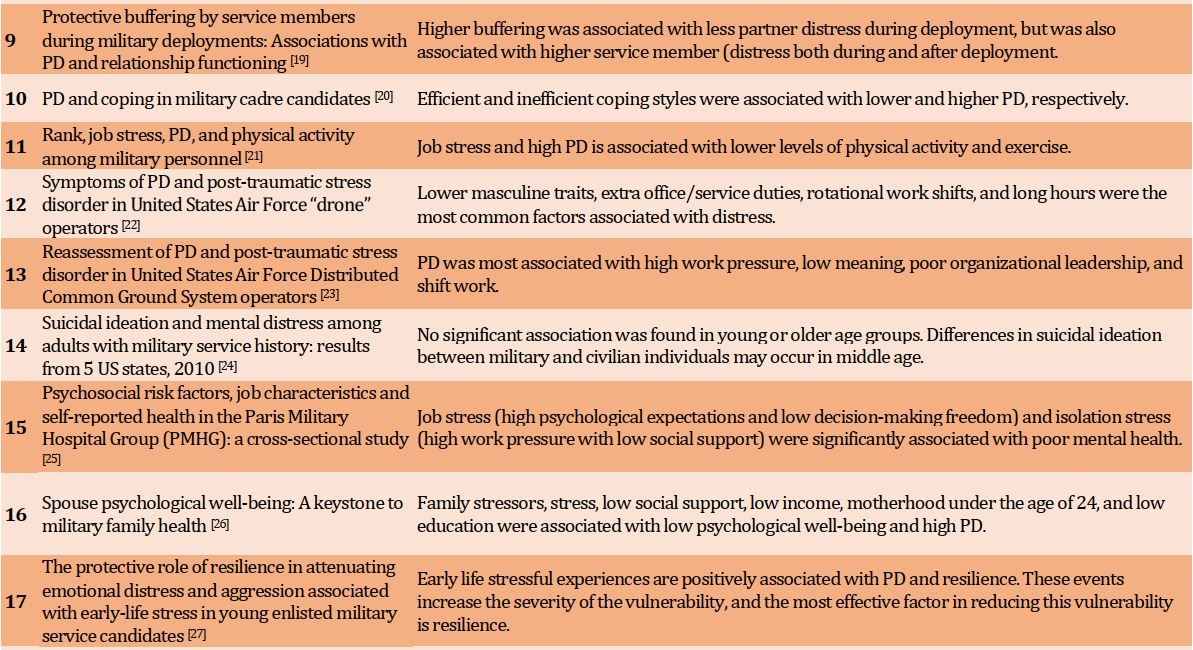

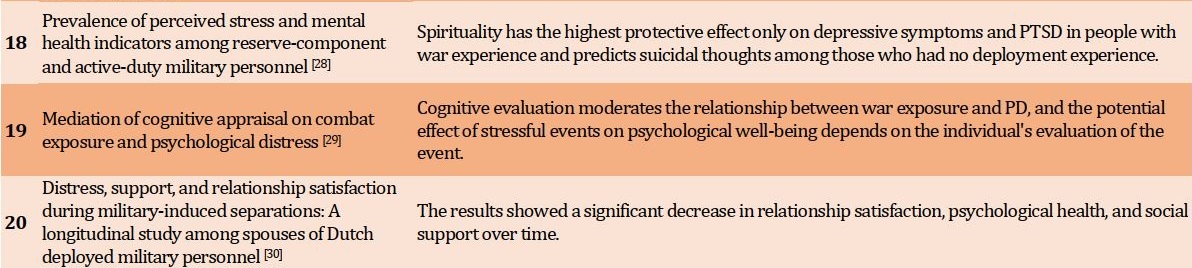

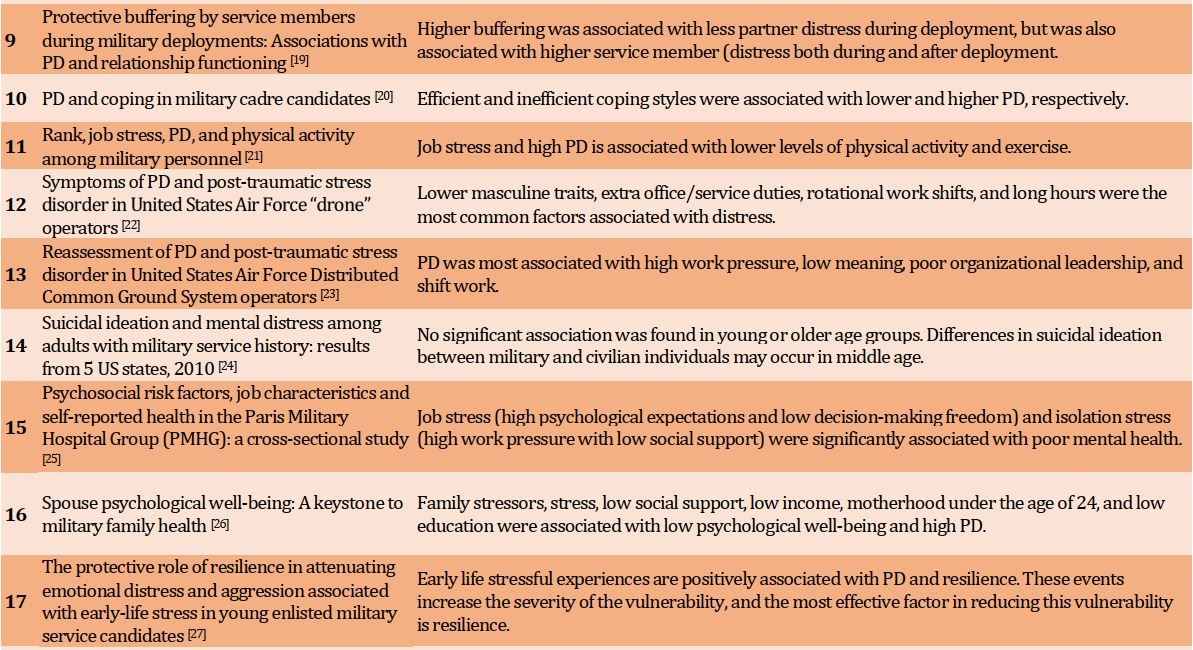

In the first stage, it was found 25 studies related to the PD of the armed forces and synonymous terms. Factors affecting PD were extracted and presented in Table 1.

Stage 2

The participants of the study were 15 people (1 woman and 14 men). The participants were in the age range of 33 to 60 and included 8 psychologists and 7 staff with enough history of military experiences who were familiar with the PD of military environments. In the present study, participants referred to two general categories that contribute PD of military personnel. The first category included demands in four subcategories: Military related demands, Occupational-organizational demands, Individual-occupational demands, and personal demands. The second category was resources, including personal resources and job resources. The data from interviews showed 395 concepts in six subcategories, and two categories were obtained in this context (Table 2).

Demands

1. Military related demands

In the subcategory of military related demands, eight codes were found. These codes included the right to protest, social position for militarists, punishments and encouragement, military culture, military isolation, family satisfaction with being military, army facilities for families, and overcoming military identity.

Regarding the concept of protest rights, participants acknowledged that employees in some cases could not object to the decision made or express their opinions freely. For example, participant No. 11 said: “The inability of employees to protest is not recognized so that subordinates can’t express peaceful protest.”

Regarding the concept of social status, participant No. 4 said: “The weak social status of military personnel in society is one of the things that can increase the psychological distress of employees.”

Table 1) Factors affecting PD, extracted from the review of previous studies

Table 2) Concepts extracted from participant’s experiences on psychological distress

The reward and punishment system is another concept that has been raised in the field of organization and leadership. As participant No. 5 said: “Lack of proper reward and unbalanced and unstable reward distribution system are some of the things that lead to distress.”

Several concepts, including daily practices, hierarchy, inflexible commands, missions, ranks, and military parade, are categorized as military culture. Because these concepts are specific to military occupations and for better management of codes, they are placed under the concept of military culture.

In the concept of daily practices, experts introduced exercises that military personnel are required to perform daily. Participant No. 7 said: “Practicing every day can be a kind of distress for a military person.” Also, about the hierarchy of inflexible commands, participants talked about the lack of up-to-date commands, inflexibility, and strictness in executing commands. Participant No. 15 said: “Commands that are not in line with the conditions and have little flexibility lead to the distress of military personnel.”

In the lack of support of family, participants acknowledged that in military organizations, they do not pay enough attention to families and their well-being. Participant No. 6 stated: “In military organizations, more attention should be paid to the welfare facilities of families, and more time should be spent for them.”

Concerning the concept of social isolation, participants acknowledged that military personnel, as they usually live in military settlements, are far from the heart of society and that separation can lead to distress for them and their families. “Social segregation includes separate workplaces, separate living spaces.”

About family satisfaction, participant No. 3 said: “If the family accepts military service, they will more easily tolerate its problems.”

The next concept was the dominance of military identity over individual identity. For example, participant No. 9 said: “Another argument is the role of individual identity in military personnel. Individuality decreases, and the military role becomes more prominent. He is an individual, and his role is not his personal personality and identity.”

2. Occupational-organizational demands

Concepts raised in the category of demands were occupational-organizational demands, which included role problems, quantitative demands, appropriate training, predictability, quality of leadership, and salary.

Regarding the concept of role problems, participant No. 4 said: “A military person may not consider a job role appropriate for him/her, and the role assigned to him/her may be heavier than his/her ability, and this person is more likely to fail.

In the concept of quantitative demands, participants talked about working hours that are sooner or later than usual. For example, Specialist No. 9 said: “Militarists usually arrive at work earlier than usual.”

Regarding the concept of leadership, the participants emphasized the leadership style and characteristics of the leaders. For example, participant No. 6 said: “The characteristics of the leaders are very important in increasing the distress of personnel. A leader creates so much hell for his staff that the distress of all the personnel increases, and another commander removes the distress from the personnel due to his special companionship and management.”

Regarding salary, financial difficulties were raised, such as housing problems, economic problems, and weak welfare facilities. Participant No. 15 said: “One of the most important causes of distress in military personnel can be financial problems.”

3. Individual-occupational demands

This subcategory included variables that depend on both the job and the individual characteristics of the employees. These concepts consisted of commitment, meaning of work, and family-work conflict. Finding meaning in work was another concept that experts said played an important role in reducing staff PD. For example, participant No. 5 said: “It is very important for a person to have a sublime meaning for what he does, especially in the armed forces.”

The concept of family-work conflict is like transferring a stressful work environment to the family or a military person being absent due to a mission. Participant No. 6 introduced this concept and said: “The absence of a military person in different life situations due to missions and busy schedules is another factor that causes distress.”

4. Personal demands

This subcategory included concepts that are only relevant to the person, such as physical and psychological problems and diseases.

Concerning family conflicts, for example, participant No. 2 said: “The relationship between the couple and the relationship between parents and children have a huge impact on the distress of military personnel.”

Resources

1. Personal resources

In the subcategory of personal resources, participants raised concepts that reduce distress and make a person resistant to it, such as hope, adherence to ethics, biological readiness, creativity, emotional intelligence, attitude, and resilience.

Hope is another concept that participants came up with. For example, participant No. 10 said: Feeling hopelessness causes a lot of distress and should be avoided to eliminate it.

About adherence to ethics, participant No. 6 said: “As a military, if I try to reach morality and ethics, many problems will be solved, but now for us, individual interests are a priority, and major people suffer due to not achieving their priorities.”

The participants also mentioned biological readiness. For example, participant No. 1 said: "Fear has a biological basis, and some people are more cautious and take less risk." The biological basis of fear is important in individuals.

Creativity was also a personality trait that was mentioned by the participants. For example, participant No. 7 said: “A person's level of creativity is very important in reducing stress.”

Emotional intelligence was also a personality trait that was mentioned by the participants. For example, participant No. 8 said: “A person's level of awareness of their emotions and how they manage them play a role in a person's level of distress.”

Individual attitudes were also personality traits that were mentioned by the participants. For example, participant No. 3 said: “The stress perceived by different people can affect a person's distress rate.”

Resilience in military personnel was also a personality trait that could reduce distress. For example, participant No. 1 said: “Military personnel must have high resilience and strengthen it to perform properly in sensitive situations.”

2. Job resources

This subcategory included social support, trust, and justice. Participant No. 11 said: “The organization's psychological support of staff is important. For example, personnel who have a problem can be better handled if the organization and the commander understand them.”

Another concept was justice. For example, participant No. 12 said: “Justice can make employees feel good.”

The concept of trust in the organization is another issue that raised. For example, participant No. 5 said, "I think the sense of belonging and confidence is vital. It feels like you could do something for me."

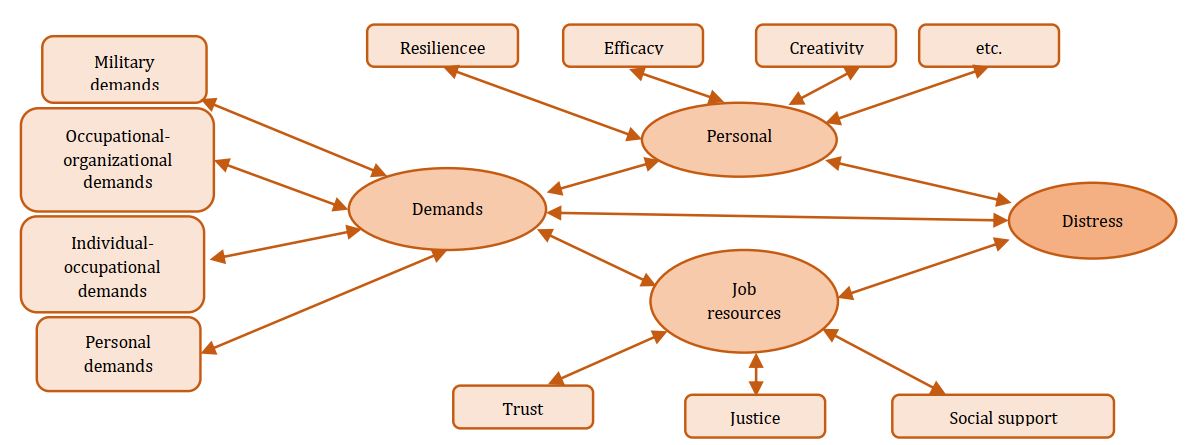

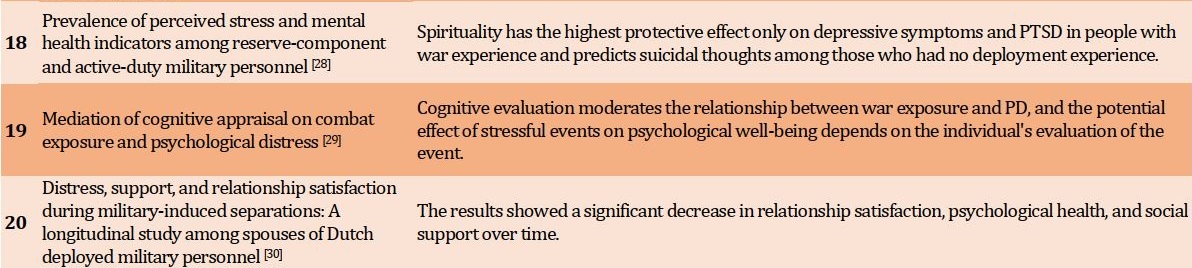

In Figure 2, the factors extracted from the study were included in the demand-resource model.

Figure 2) Iranian military JD-R model

Discussion

The present qualitative study examined the PD factors in Iranian military personnel. Findings included two main categories, including demands and resources. These concepts included the right to protest, punishments and encouragement, military culture, social position, military isolation, family satisfaction with being military, army facilities for families, and overcoming military identity. Organizational structures, arrangement, and codes determine the meaning of a military culture which is significantly unique. Military staff and their family are limited by military rules, regulations, conventions, ethics, and values that are different from those of civilians [36]. The military culture contains both ceremonial discipline acts, like shining shoes, uniforms, and salutes, as well as a functional discipline where commanders’ orders are followed by service members. For example, the chain of command is a hierarchical structure of seniors and subordinates [36]. Leaders in boot camp deconstruct the recruits’ civilian status and give them a new identity. The recruits go through a harsh, humiliating, physically and emotionally exhausting process. They are exposed to their new norms, languages, codes, and identities. In the military, cutting hair, common uniforms, enduring hard situations, and collectively eating, exercising and accommodating, as well as being kept apart from friends and the family, are necessary [36]. Veterans who had reported higher levels of the military identity, had also reported higher levels of PD [37].

In any form of social congruity and culture, specific worldviews are developed and shared. In 1978, Sue defined a worldview and its importance to the formation and maintenance of a person’s identity by stating that it was related to the individual’s perception of and relationship with the world. In other words, these acted as a “filter” through which one read reality [38].

Haslam argued Social Identification Theory (SIT). Social identification played a key role in establishing the important organizational behaviors and higher levels of physical and emotional well-being. Van Dick et al. argued that the main prediction of SIT for organizational contexts is that the more an individual defines him or herself in terms of a member of an organizational group (for instance, the Armed Forces), the more his/her attitudes and behaviors were governed by this group membership [39].

Other concepts raised in the context of occupational demands were role problems, quantitative demands, appropriate training, predictability, quality of leadership, and salary. These concepts rely on theoretical frameworks, such as the Effort-Reward Imbalance model or the Job Demands-Control model, that provide insights regarding the impact of an individual’s job design. In 2002, Michie and Williams showed that the most common work factors associated with psychological illness are work demands (long hours, workload, and pressure), a lack of control over work, and poor support from managers, as well as, the Organization Climate (OC) that concerns the meaning employees attach to the tangible policies, practices, and procedures they experience in their work situation including (1) leadership characteristics, (2) group behaviors and relationships, (3) communication, and (4) structural attributes of the quality of work life [40].

Commitment, the meaning of work, and family-work conflict were concepts that participants raised in the individual-occupational demands subcategory. Work-family conflicts significantly lead to health consequences as well as burnout. Baruch-Feldman et al. showed that work-family support was negatively associated with burnout. Parasuraman et al. found significant indirect effects of emotional support on job satisfaction and life stress with a mediating role of family-work interaction [41]. Organizational commitment is partly the result of intrinsic and partial characteristics of the individual and how employees perceive the organization and the immediate role of their work. Also, organizational identity leads to the individual's high effort to achieve organizational goals [42].

About personal demand, concepts including family conflict, psychological problems, and physical illness were found. To get higher performance and behavior, individuals set requirements for themselves that force them to exert efforts in their work and are consequently connected with physical and psychological costs; these requirements are termed personal demand. As Bakker said, personal demands and personal resources should be studied together [43]. In this study, concepts such as hope, adherence to ethics, biological readiness, creativity, emotional intelligence, attitude, and resilience were found. He argued that the nature of the personal demands would define the process as a motivational process or health impairment process. Personal demands are considered challenges for employees that energize or motivate them to participate in their work. Similarly, personal resources also have a positive attitude towards the work environment, which is evident from various studies. Personal demands and personal resources lead to an opportunity to meet basic needs, which in turn creates a positive connection with the work environment [43].

Job resources included social support, trust, and justice. According to literature, organizational climate encompasses a broad range of individual and contextual level factors that form the immediate environment of individual workers. Organizational justice is a key aspect of a supportive climate. It has been found that organizational justice affects outcomes of an organization, including welfare, satisfaction, emotional fatigue, and accomplishment [44]. In general, Judge and Colquitt noted: “Justice can reduce the uncertainty and lack of control that are at the heart of feelings of stress”. In addition, organizational justice theories implicitly include distress due to imbalance and motivation to change the situation. Presumably, injustice, similar to what Lazarus and Folkman (1984) stated, is strongly related to an anticipated threat and thereby lies at the heart of the primary appraisal processes [45].

The current study tested the strain hypotheses based on the Job Demand-Control-Support (JDCS) model framework. Specifically, the direct effect of job demands on depression, as well as the moderating role of job control, social support, and their joint effect (job control × social support) on the job demand-depression link were investigated. Social support and, to a partial extent, job control buffered the negative effects of job demands on depression. High social support intensified the buffering effect of job control on the organizational demands-depression link. The concept of the JDCS model is quite supported by the results and give more perception of processes resulting in police officers’ illness in their workplaces [46].

Military organizations and leaders should consider the factors of psychological distress raised by specialists and assign policies to improve the mental health of military staff members.

Conclusion

Different factors affect the military members’ psychological distress, which are divided into two categories and six subcategories: Demands (military related demands, occupational-organizational demands, individual-occupational demands, and personal demands) and Resources (personal resources and job resources).

Acknowledgements: The researchers of the present study appreciate all participants who helped us in this study.

Ethical Permission: This research was approved by the ethical code IR.BMSU.REC.1399.341.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Alizadeh A (First Author), Main Researcher (30%); Javanmard Y (Second Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Dowran B (Third Author), Methodologist (15%); Azizi M (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (10%); Salimi SH (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher (%)

Funding: This article is a part of a doctoral dissertation and was done with the financial support of Baqiyatullah University of Medical Sciences.

High-risk occupations have remarkable levels of psychological and physical stress [1]. Encountering potentially traumatic events are common in the occupations of these people as a part of their job [2], and research has demonstrated the connection between passing such events and mental health problems among military staff members, police, as well as rescue and recovery workers [3].

While the military is defending the borders of the countries, it is also responsible for helping relief organizations when natural disasters and unexpected events occur. Hence, to constantly be well prepared and perfectly healthy is necessary. Instead, the Armed Forces’ nature and missions are so special that their related organization is continually dynamic and efficient. Therefore, their organization is more likely to change than others, which brings inconsistency and stress [4]. Certainly, mental health problem rates have broadly been analyzed in the military, particularly among troops on combat deployments [3].

Psychological Distress (PD) is an unfavorable emotional state which has physical and emotional manifestations and can consider an indicator of psychological problems examined in studies and clinical collections with psychological, social, and behavioral symptoms which are connected to anxiety and depression [2, 5]. PD can be considered as an emotional suffering that poses a real or perceived physical or psychological threat to an individual. A person's emotional challenges and psychological reactions to fit into the environment are defined by PD as a key indicator that negatively influences the occupational capacity of a person, his/her family life, and well-being [6].

Psychophysiological and behavioral symptoms that are not specific to a given mental pathology illustrate PD, which is a mental health consequence. Symptoms such as anxiety, depressive responses, irritability, descending intellectual capacity, fatigue, sleepiness, etc., and PD seem to be prevented by conditions of a work organization related to skill application, decision authority, social support in the workplace, and satisfaction while psychological, physical and contractual needs usually increase it [7, 8].

Military jobs are constantly faced with psychological distress and physical pressures such as lack of sleep, recreation, high monotony of the environment, and ceremonial and repetitive tasks. High job stress, low autonomy, and long working hours are other stressors of a military work environment. Some military personnel are constantly and intensely lonely and do not have the opportunity to receive assistance. These demands can lead to adjustment difficulties that manifest themselves in the form of distress and psychological disorders, and even suicide attempts [9]. Research has demonstrated the connection between traumatic, unpredictable events [3], and also rapid changes [4] with PD in the military.

The psychological distress of military jobs has major and dramatic consequences in the family and organizational environment. Weakening of individual and group performance, low accuracy at work, emotional problems, alcohol and drug abuse, misplaced violence, lack of cooperation and partnership with the commander, withdrawal from operational areas, divorce and marital and moral problems, and difficulty in decision-making are the consequences of PD in military personnel [10].

Military occupations in which personnel face high demands from the unit lead to greater psychological distress. The Job Demand-Resource Model (JD-R) classifies the factors affecting employee well-being into two different categories: job demands and job resources. Job demand includes those factors (such as time pressure and workload) that reduce health and energy and cause severe mental disorders over some time and ultimately, poor employee performance. In contrast, job resources include a variety of factors (such as management support, supervisor feedback, skills, and independence) that motivate employees and reduce the negative consequences of the job. In this model, two paths are identified: the destructive path of health and the path of motivation. In the destructive path of health, increasing demands and reducing resources can harm a person's health and have negative consequences such as burnout. While on the motivational path, increasing resources (rather than just reducing demand) can lead to increased employees' motivation and thus, better organizational performance (Figure 1) [11].

Figure 1) The job demand resource model [11]

Surprisingly, in our search, we did not find a study that comprehensively examines the factors influencing employees' psychological distress. Therefore, it is necessary to examine this concept in military personnel in depth without labeling it as a disorder and fear of stigma. In addition, especially this research type among the Iranian military personnel had a weak background in studies. Hence, there was a need for a better understanding of military psychological distress. We aimed to address the causes and patterns of PD in military personnel in detail and fundamentally. Thus, in examining this concept, the question arose in the research literature and the views of military personnel: “What factors contributed to the occurrence of psychological distress?” Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the factors that caused PD in Iranian military staff members.

Participants and Methods

Study design

This study is a qualitative research, which was done in two steps on PD among military personnel. The first stage was a brief review. We studied texts related to the factors influencing "PD in the military" in ScienceDirect, PubMed, Medline, IranDoc, SID, Ovid, ProQuest, IranMedex and Google Scholar, and other related texts from 2010 to 2020. The keywords PD, depression, anxiety, and anger with the keywords military, armed forces, soldier, and family were searched. Then we carefully read the found articles and texts. Moreover, we extracted the factors affecting PD from the texts. The second stage was the stage of interviewing experts including interviews with military psychologists. The researchers performed an in-depth direct analysis of the military experiences. The results were presented as codes, subcategories, and categories using an inductive approach. Finally, the results were organized into the framework of the JD-R model.

The statistical population of the first stage was all studies in the research literature related to the PD of the military. For the second stage, Participants were selected through the purposive sampling method from several universities. Selection of samples was based on the objective of the study. Research samples included groups of military personnel and military psychologists. Interviews with personnel were done at their workplaces. The endpoint for sample selection was reaching data saturation. Data collection and analysis for this study were done from October 10th, 2019 to April 16th, 2020, through in-depth semi-structured interviews with the participants. Interviews with participants began with an explanation of the psychological distress concept, and according to the interview guidelines, general open-ended questions were asked, “In your opinion, what factors cause psychological distress in military personnel?” Or “What factors cause discomfort and anxiety in military personnel?” Then, depending on the context of the responses, the interviewer continued with exploratory questions, “Can you please give an example?” or “Could you explain more?” to clarify concepts for the researcher and participants. The interview duration ranged between 45 and 60 minutes, depending on the willingness and situation of the respondent. Finally, by adding this question, “Would you like to add anything else?” the possibility of having experiences or cases beyond the author's imagination was examined.

After each interview, verbatim transcriptions were prepared using MAXQDA 10. Each entire interview was considered as an analysis unit. The transcribed script was read several times to become familiar with the context. Then, the meaning units were identified. After that, the condensed meaning units were abstracted and labeled with a code, and compared based on differences and similarities, and sorted into sub-categories and categories. Finally, the results were organized into the framework of the JD-R model.

Trustworthiness of data

Several strategies were used to ensure the credibility of the data. In this regard, data gathering lasted about one month, and the researchers were deeply oriented to data and the atmosphere of the field during this time. Some strategies were used to ensure the credibility of the data, including peer review (data and their interpretations were checked by other researchers) and member checking (data were rechecked by participants and, our interpretations from data were reviewed and confirmed by them).

Findings

Stage 1

In the first stage, it was found 25 studies related to the PD of the armed forces and synonymous terms. Factors affecting PD were extracted and presented in Table 1.

Stage 2

The participants of the study were 15 people (1 woman and 14 men). The participants were in the age range of 33 to 60 and included 8 psychologists and 7 staff with enough history of military experiences who were familiar with the PD of military environments. In the present study, participants referred to two general categories that contribute PD of military personnel. The first category included demands in four subcategories: Military related demands, Occupational-organizational demands, Individual-occupational demands, and personal demands. The second category was resources, including personal resources and job resources. The data from interviews showed 395 concepts in six subcategories, and two categories were obtained in this context (Table 2).

Demands

1. Military related demands

In the subcategory of military related demands, eight codes were found. These codes included the right to protest, social position for militarists, punishments and encouragement, military culture, military isolation, family satisfaction with being military, army facilities for families, and overcoming military identity.

Regarding the concept of protest rights, participants acknowledged that employees in some cases could not object to the decision made or express their opinions freely. For example, participant No. 11 said: “The inability of employees to protest is not recognized so that subordinates can’t express peaceful protest.”

Regarding the concept of social status, participant No. 4 said: “The weak social status of military personnel in society is one of the things that can increase the psychological distress of employees.”

Table 1) Factors affecting PD, extracted from the review of previous studies

Table 2) Concepts extracted from participant’s experiences on psychological distress

The reward and punishment system is another concept that has been raised in the field of organization and leadership. As participant No. 5 said: “Lack of proper reward and unbalanced and unstable reward distribution system are some of the things that lead to distress.”

Several concepts, including daily practices, hierarchy, inflexible commands, missions, ranks, and military parade, are categorized as military culture. Because these concepts are specific to military occupations and for better management of codes, they are placed under the concept of military culture.

In the concept of daily practices, experts introduced exercises that military personnel are required to perform daily. Participant No. 7 said: “Practicing every day can be a kind of distress for a military person.” Also, about the hierarchy of inflexible commands, participants talked about the lack of up-to-date commands, inflexibility, and strictness in executing commands. Participant No. 15 said: “Commands that are not in line with the conditions and have little flexibility lead to the distress of military personnel.”

In the lack of support of family, participants acknowledged that in military organizations, they do not pay enough attention to families and their well-being. Participant No. 6 stated: “In military organizations, more attention should be paid to the welfare facilities of families, and more time should be spent for them.”

Concerning the concept of social isolation, participants acknowledged that military personnel, as they usually live in military settlements, are far from the heart of society and that separation can lead to distress for them and their families. “Social segregation includes separate workplaces, separate living spaces.”

About family satisfaction, participant No. 3 said: “If the family accepts military service, they will more easily tolerate its problems.”

The next concept was the dominance of military identity over individual identity. For example, participant No. 9 said: “Another argument is the role of individual identity in military personnel. Individuality decreases, and the military role becomes more prominent. He is an individual, and his role is not his personal personality and identity.”

2. Occupational-organizational demands

Concepts raised in the category of demands were occupational-organizational demands, which included role problems, quantitative demands, appropriate training, predictability, quality of leadership, and salary.

Regarding the concept of role problems, participant No. 4 said: “A military person may not consider a job role appropriate for him/her, and the role assigned to him/her may be heavier than his/her ability, and this person is more likely to fail.

In the concept of quantitative demands, participants talked about working hours that are sooner or later than usual. For example, Specialist No. 9 said: “Militarists usually arrive at work earlier than usual.”

Regarding the concept of leadership, the participants emphasized the leadership style and characteristics of the leaders. For example, participant No. 6 said: “The characteristics of the leaders are very important in increasing the distress of personnel. A leader creates so much hell for his staff that the distress of all the personnel increases, and another commander removes the distress from the personnel due to his special companionship and management.”

Regarding salary, financial difficulties were raised, such as housing problems, economic problems, and weak welfare facilities. Participant No. 15 said: “One of the most important causes of distress in military personnel can be financial problems.”

3. Individual-occupational demands

This subcategory included variables that depend on both the job and the individual characteristics of the employees. These concepts consisted of commitment, meaning of work, and family-work conflict. Finding meaning in work was another concept that experts said played an important role in reducing staff PD. For example, participant No. 5 said: “It is very important for a person to have a sublime meaning for what he does, especially in the armed forces.”

The concept of family-work conflict is like transferring a stressful work environment to the family or a military person being absent due to a mission. Participant No. 6 introduced this concept and said: “The absence of a military person in different life situations due to missions and busy schedules is another factor that causes distress.”

4. Personal demands

This subcategory included concepts that are only relevant to the person, such as physical and psychological problems and diseases.

Concerning family conflicts, for example, participant No. 2 said: “The relationship between the couple and the relationship between parents and children have a huge impact on the distress of military personnel.”

Resources

1. Personal resources

In the subcategory of personal resources, participants raised concepts that reduce distress and make a person resistant to it, such as hope, adherence to ethics, biological readiness, creativity, emotional intelligence, attitude, and resilience.

Hope is another concept that participants came up with. For example, participant No. 10 said: Feeling hopelessness causes a lot of distress and should be avoided to eliminate it.

About adherence to ethics, participant No. 6 said: “As a military, if I try to reach morality and ethics, many problems will be solved, but now for us, individual interests are a priority, and major people suffer due to not achieving their priorities.”

The participants also mentioned biological readiness. For example, participant No. 1 said: "Fear has a biological basis, and some people are more cautious and take less risk." The biological basis of fear is important in individuals.

Creativity was also a personality trait that was mentioned by the participants. For example, participant No. 7 said: “A person's level of creativity is very important in reducing stress.”

Emotional intelligence was also a personality trait that was mentioned by the participants. For example, participant No. 8 said: “A person's level of awareness of their emotions and how they manage them play a role in a person's level of distress.”

Individual attitudes were also personality traits that were mentioned by the participants. For example, participant No. 3 said: “The stress perceived by different people can affect a person's distress rate.”

Resilience in military personnel was also a personality trait that could reduce distress. For example, participant No. 1 said: “Military personnel must have high resilience and strengthen it to perform properly in sensitive situations.”

2. Job resources

This subcategory included social support, trust, and justice. Participant No. 11 said: “The organization's psychological support of staff is important. For example, personnel who have a problem can be better handled if the organization and the commander understand them.”

Another concept was justice. For example, participant No. 12 said: “Justice can make employees feel good.”

The concept of trust in the organization is another issue that raised. For example, participant No. 5 said, "I think the sense of belonging and confidence is vital. It feels like you could do something for me."

In Figure 2, the factors extracted from the study were included in the demand-resource model.

Figure 2) Iranian military JD-R model

Discussion

The present qualitative study examined the PD factors in Iranian military personnel. Findings included two main categories, including demands and resources. These concepts included the right to protest, punishments and encouragement, military culture, social position, military isolation, family satisfaction with being military, army facilities for families, and overcoming military identity. Organizational structures, arrangement, and codes determine the meaning of a military culture which is significantly unique. Military staff and their family are limited by military rules, regulations, conventions, ethics, and values that are different from those of civilians [36]. The military culture contains both ceremonial discipline acts, like shining shoes, uniforms, and salutes, as well as a functional discipline where commanders’ orders are followed by service members. For example, the chain of command is a hierarchical structure of seniors and subordinates [36]. Leaders in boot camp deconstruct the recruits’ civilian status and give them a new identity. The recruits go through a harsh, humiliating, physically and emotionally exhausting process. They are exposed to their new norms, languages, codes, and identities. In the military, cutting hair, common uniforms, enduring hard situations, and collectively eating, exercising and accommodating, as well as being kept apart from friends and the family, are necessary [36]. Veterans who had reported higher levels of the military identity, had also reported higher levels of PD [37].

In any form of social congruity and culture, specific worldviews are developed and shared. In 1978, Sue defined a worldview and its importance to the formation and maintenance of a person’s identity by stating that it was related to the individual’s perception of and relationship with the world. In other words, these acted as a “filter” through which one read reality [38].

Haslam argued Social Identification Theory (SIT). Social identification played a key role in establishing the important organizational behaviors and higher levels of physical and emotional well-being. Van Dick et al. argued that the main prediction of SIT for organizational contexts is that the more an individual defines him or herself in terms of a member of an organizational group (for instance, the Armed Forces), the more his/her attitudes and behaviors were governed by this group membership [39].

Other concepts raised in the context of occupational demands were role problems, quantitative demands, appropriate training, predictability, quality of leadership, and salary. These concepts rely on theoretical frameworks, such as the Effort-Reward Imbalance model or the Job Demands-Control model, that provide insights regarding the impact of an individual’s job design. In 2002, Michie and Williams showed that the most common work factors associated with psychological illness are work demands (long hours, workload, and pressure), a lack of control over work, and poor support from managers, as well as, the Organization Climate (OC) that concerns the meaning employees attach to the tangible policies, practices, and procedures they experience in their work situation including (1) leadership characteristics, (2) group behaviors and relationships, (3) communication, and (4) structural attributes of the quality of work life [40].

Commitment, the meaning of work, and family-work conflict were concepts that participants raised in the individual-occupational demands subcategory. Work-family conflicts significantly lead to health consequences as well as burnout. Baruch-Feldman et al. showed that work-family support was negatively associated with burnout. Parasuraman et al. found significant indirect effects of emotional support on job satisfaction and life stress with a mediating role of family-work interaction [41]. Organizational commitment is partly the result of intrinsic and partial characteristics of the individual and how employees perceive the organization and the immediate role of their work. Also, organizational identity leads to the individual's high effort to achieve organizational goals [42].

About personal demand, concepts including family conflict, psychological problems, and physical illness were found. To get higher performance and behavior, individuals set requirements for themselves that force them to exert efforts in their work and are consequently connected with physical and psychological costs; these requirements are termed personal demand. As Bakker said, personal demands and personal resources should be studied together [43]. In this study, concepts such as hope, adherence to ethics, biological readiness, creativity, emotional intelligence, attitude, and resilience were found. He argued that the nature of the personal demands would define the process as a motivational process or health impairment process. Personal demands are considered challenges for employees that energize or motivate them to participate in their work. Similarly, personal resources also have a positive attitude towards the work environment, which is evident from various studies. Personal demands and personal resources lead to an opportunity to meet basic needs, which in turn creates a positive connection with the work environment [43].

Job resources included social support, trust, and justice. According to literature, organizational climate encompasses a broad range of individual and contextual level factors that form the immediate environment of individual workers. Organizational justice is a key aspect of a supportive climate. It has been found that organizational justice affects outcomes of an organization, including welfare, satisfaction, emotional fatigue, and accomplishment [44]. In general, Judge and Colquitt noted: “Justice can reduce the uncertainty and lack of control that are at the heart of feelings of stress”. In addition, organizational justice theories implicitly include distress due to imbalance and motivation to change the situation. Presumably, injustice, similar to what Lazarus and Folkman (1984) stated, is strongly related to an anticipated threat and thereby lies at the heart of the primary appraisal processes [45].

The current study tested the strain hypotheses based on the Job Demand-Control-Support (JDCS) model framework. Specifically, the direct effect of job demands on depression, as well as the moderating role of job control, social support, and their joint effect (job control × social support) on the job demand-depression link were investigated. Social support and, to a partial extent, job control buffered the negative effects of job demands on depression. High social support intensified the buffering effect of job control on the organizational demands-depression link. The concept of the JDCS model is quite supported by the results and give more perception of processes resulting in police officers’ illness in their workplaces [46].

Military organizations and leaders should consider the factors of psychological distress raised by specialists and assign policies to improve the mental health of military staff members.

Conclusion

Different factors affect the military members’ psychological distress, which are divided into two categories and six subcategories: Demands (military related demands, occupational-organizational demands, individual-occupational demands, and personal demands) and Resources (personal resources and job resources).

Acknowledgements: The researchers of the present study appreciate all participants who helped us in this study.

Ethical Permission: This research was approved by the ethical code IR.BMSU.REC.1399.341.

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors’ Contribution: Alizadeh A (First Author), Main Researcher (30%); Javanmard Y (Second Author), Introduction Writer (15%); Dowran B (Third Author), Methodologist (15%); Azizi M (Fourth Author), Discussion Writer (10%); Salimi SH (Fifth Author), Assistant Researcher (%)

Funding: This article is a part of a doctoral dissertation and was done with the financial support of Baqiyatullah University of Medical Sciences.

Keywords:

References

1. Khankeh H, Alizadeh A, Nouri M, Bidaki R, Azizi M. Long-term consequences of the psychological distress in Iranian emergency medical personnel: a qualitative research. Health Emerge Disast Q. 2022;8(1):7-14. [Link] [DOI:10.32598/hdq.8.1.318.2]

2. Azizi M, Ebadi A, Ostadtaghizadeh A, Dehghani Tafti A, Roudini J, Barati M, et al. Psychological distress model among Iranian pre-hospital personnel in disasters: a grounded theory study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:689226. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689226]

3. Adler AB, Saboe KN, Anderson J, Sipos ML, Thomas JL. Behavioral health leadership: New directions in occupational mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):484. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11920-014-0484-6]

4. Balouchi Anaraki M, Amini M, Azad E, Shirmardi A. The mental health promotion programs and strategies used in US, UK, Russia and Iran's military organizations: systematic review. J Mil Med. 2019;21(3):208-20. [Persian] [Link]

5. Bessaha ML. Factor structure of the kessler psychological distress scale (K6) among emerging adults. Res Soc Work Pract. 2017;27(5):616-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1049731515594425]

6. Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Lapointe L, Dubois M-F, Almirall J. Psychological distress and multimorbidity in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(5):417-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1370/afm.528]

7. Marchand A, Drapeau A, Beaulieu-Prévost D. Psychological distress in Canada: The role of employment and reasons of non-employment. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58(6):596-604. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0020764011418404]

8. Azizi M, Bidaki R, Ebadi A, Ostadtaghizadeh A, Tafti AD, Hajebi A, et al. Psychological distress management in iranian emergency prehospital providers: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:442. [Link]

9. Azadmarzabadi E, Niknafas S. Models of opposing against job stress among military staff. Payavard. 2016;10(4):299-310. [Persian] [Link]

10. Skomorovsky A, LeBlanc MM. Intimate partner violence in the Canadian Armed Forces: Psychological distress and the role of individual factors among military spouses. Mil Med. 2017;182(1-2):e1568-75. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00566]

11. Demerouti E, Bakker AB. The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J Indust Psychol. 2011;37(2):1-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974]

12. Wolfe-Clark AL, Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Reynolds ML, Fuessel-Herrmann D, White KL, et al. Child sexual abuse, military sexual trauma, and psychological distress among male military personnel and veterans. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2017;10(2):121-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s40653-017-0144-1]

13. Hughes JM, Ulmer CS, Hastings SN, Gierisch JM, Workgroup M-AVM, Howard MO. Sleep, resilience, and psychological distress in United States military Veterans. Mil Psychol. 2018;30(5):404-14. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08995605.2018.1478551]

14. Manalo M. The role of self-compassion in the relationship between moral injury and psychological distress among military veterans [Dissertation]. San Bernardino: California State University; 2019. [Link]

15. Verma R, Singh R. Last held military rank and wellbeing (psychological distress) of army ex-servicemen (non-commissioned officers). Int J Indian Psychol. 2016;3(4):25. [Link] [DOI:10.25215/0304.135]

16. Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Erbes CR, Polusny MA, Rath CM, Sponheim SR. Predictors of emotional distress reported by soldiers in the combat zone. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(7):470-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.10.010]

17. de Souza ER, de Souza Minayo MC, eSilva JG, de Oliveira Pires T. Factors associated with psychological distress among military police in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2012;28(7):1297-311. [Portuguese] [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0102-311X2012000700008]

18. Moreno JL, Nabity PS, Kanzler KE, Bryan CJ, McGeary CA, McGeary DD. Negative life events (NLEs) contributing to psychological distress, pain, and disability in a US military sample. Mil Med. 2019;184(1-2):e148-55. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/milmed/usy259]

19. Carter SP, Renshaw KD, Curby TW, Allen ES, Markman HJ, Stanley SM. Protective buffering by service members during military deployments: Associations with psychological distress and relationship functioning. Fam Process. 2020;59(2):525-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/famp.12426]

20. Nakkas C, Annen H, Brand S. Psychological distress and coping in military cadre candidates. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2237-43. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S113220]

21. Martins LCX, Lopes CS. Rank, job stress, psychological distress and physical activity among military personnel. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-13-716]

22. Chappelle WL, McDonald KD, Prince L, Goodman T, Ray-Sannerud BN, Thompson W. Symptoms of psychological distress and post-traumatic stress disorder in United States Air Force "drone" operators. Mil Med. 2014;179(8 Suppl):63-70. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00501]

23. Prince L, Chappelle WL, McDonald KD, Goodman T, Cowper S, Thompson W. Reassessment of psychological distress and post-traumatic stress disorder in United States Air Force Distributed Common Ground System operators. Mil Med. 2015;180(3 Suppl):171-8. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00397]

24. Blosnich JR, Gordon AJ, Bossarte RM. Suicidal ideation and mental distress among adults with military service history: results from 5 US states, 2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 4):S595-602. [Link] [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302064]

25. Ferrand J-F, Verret C, Trichereau J, Rondier J-P, Viance P, Migliani R. Psychosocial risk factors, job characteristics and self-reported health in the Paris Military Hospital Group (PMHG): a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e000999. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000999]

26. Green S, Nurius PS, Lester P. Spouse psychological well-being: A keystone to military family health. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2013;23(6):753-68. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10911359.2013.795068]

27. Kim J, Seok J-H, Choi K, Jon D-I, Hong HJ, Hong N, et al. The protective role of resilience in attenuating emotional distress and aggression associated with early-life stress in young enlisted military service candidates. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(11):1667-74. [Link] [DOI:10.3346/jkms.2015.30.11.1667]

28. Lane ME, Hourani LL, Bray RM, Williams J. Prevalence of perceived stress and mental health indicators among reserve-component and active-duty military personnel. Am J of Public Health. 2012;102(6):1213-20. [Link] [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300280]

29. McCuaig Edge HJ, Ivey GW. Mediation of cognitive appraisal on combat exposure and psychological distress. Mil Psychol. 2012;24(1):71-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/08995605.2012.642292]

30. Andres M. Distress, support, and relationship satisfaction during military-induced separations: A longitudinal study among spouses of Dutch deployed military personnel. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(1):22-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0033750]

31. Smith AJ, Benight CC, Cieslak R. Social support and postdeployment coping self-efficacy as predictors of distress among combat veterans. Mil Psychol. 2013;25(5):452-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/mil0000013]

32. Smith RT, True G. Warring identities: Identity conflict and the mental distress of American veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soc Ment Health. 2014;4(2):147-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/2156869313512212]

33. Nissen LR, Marott JL, Gyntelberg F, Guldager B. Danish soldiers in Iraq: perceived exposures, psychological distress, and reporting of physical symptoms. Mil Med. 2011;176(10):1138-43. [Link] [DOI:10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00094]

34. Frappell-Cooke W, Gulina M, Green K, Hacker Hughes J, Greenberg N. Does trauma risk management reduce psychological distress in deployed troops? Occup Med. 2010;60(8):645-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/occmed/kqq149]

35. Birkeland MS, Nielsen MB, Knardahl S, Heir T. Associations between work environment and psychological distress after a workplace terror attack: the importance of role expectations, predictability and leader support. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0124849. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0124849]

36. Redmond SA, Wilcox SL, Campbell S, Kim A, Finney K, Barr K, et al. A brief introduction to the military workplaceculture. Work. 2015;50(1):9-20. [Link] [DOI:10.3233/WOR-141987]

37. Zwiebach L, Lannert BK, Sherrill AM, McSweeney LB, Sprang K, Goodnight JR, et al. Military cultural competence in the context of cognitive behavioural therapy. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;12:e5. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/S1754470X18000132]

38. Weiss E, Coll JE. The influence of military culture and veteran worldviews on mental health treatment: practice implications for combat veteran help-seeking and wellness. Int J Health Wellness Soc. 2011;1(2):75-86. [Link] [DOI:10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v01i02/41168]

39. Johansen RB, Martinussen M, Kvilvang N. The influence of military identity on work engagement and burnout in the Norwegian army rapid reaction force. J Mil Stud. 2015;6(1). [Link] [DOI:10.1515/jms-2016-0196]

40. Bronkhorst B, Tummers L, Steijn B, Vijverberg D. Organizational climate and employee mental health outcomes: a systematic review of studies in health care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2014;40(3):254-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000026]

41. Blanch A, Aluja A. Social support (family and supervisor), work-family conflict, and burnout: Sex differences. Hum Relat. 2012;65(7):811-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0018726712440471]

42. Moynihan DP, Pandey SK. The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Admin Rev. 2007;67(1):40-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00695.x]

43. Waqas M, Anjum Z-U-Z, Naeem B, Anwar F. How personal resources and personal demands help in engaging employees at work? Investigating the mediating role of need based satisfaction. Econ Bus Manage. 2017;XI(3):143-57. [Link]

44. Trinkner R, TylerMacklin TR, Goff PA. Justice from within: The relations between a procedurally just organizational climate and police organizational efficiency, endorsement of democratic policing, and officer well-being. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2016;22(2):158-72. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/law0000085]

45. Lang J, Lang JWB, Adler A, Bliese PD. Work gets unfair for the depressed: cross-lagged relations between organizational justice perceptions and depressive symptoms. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(3):602-18. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0022463]

46. Baka L. Types of job demands make a difference. Testing the job demand-control-support model among Polish police officers. Int J Hum Resource Manage. 2020;31(18):2265-88. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/09585192.2018.1443962]