Volume 15, Issue 1 (2023)

Iran J War Public Health 2023, 15(1): 61-66 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2022/03/26 | Accepted: 2023/02/28 | Published: 2023/03/6

Received: 2022/03/26 | Accepted: 2023/02/28 | Published: 2023/03/6

How to cite this article

Keyhani A, Rahnejat A, Dabaghi P, Taghva A, Ebrahimi M, Nezami Asl A. Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among the Healthcare Workers Involved with COVID-19 Treatment and its Effective Factors in Military Hospitals of Iran. Iran J War Public Health 2023; 15 (1) :61-66

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1137-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1137-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Medicine Research Center, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Medicine Research Center, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (653 Views)

Introduction

At the end of December 2019, a new infectious disease caused by a new coronavirus was reported in Wuhan, China, and officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic poses unprecedented challenges to the healthcare system worldwide. The Cable News Network (CNN) has compared the impact of this pandemic on civilizations with World War II [2]. In this regard, unfortunately, this virus has infected Iran, like other countries. One of the characteristics of this disease is its rapid transmission, which endangers the mental health status of people at different levels of society [3-5]. In this regard, there is strong evidence that these people are prone to the symptoms of psychological disorders [6]. Anxiety, fear, depression, labeling, avoidance behaviors, irritability, sleep disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), marital conflicts, dependence on online networks, etc., are the most common problems and mental illnesses during the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. Findings from various studies show high COVID-19 infection among Healthcare Workers (HCWs) during the outbreak. In this regard, Wu and McGoogan found that the COVID-19 infection rate among HCWs is 3.8% [8]. Therefore, considering this high exposure, these conditions have created unprecedented challenges for healthcare systems that include uncertainty about the severity, duration, and effects of the crisis, concerns about the level of preparedness in personal and public healthcare organizations, inadequate personal protective equipment and other required medical equipment, and potential threats to for transmission of the infection to HCWs, their loved ones and colleagues [9, 10]. These conditions cause a high level of fear and anxiety in the short run and put HCWs at risk for persistent stress syndromes, professional burnout, and subclinical mental health symptom in the long run [11]. According to the results of many studies, PTSD is one of the most common disorders among HCWs during a crisis. In a study of PTSD symptoms among HCWs and public service providers during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Norway, Johnson et al. concluded that 28.9% of the HCWs had clinical and subclinical PTSD symptoms, and symptoms were significantly higher in those who worked directly with patients [12]. In a cross-sectional study of 863 HCWs involved with COVID-19 treatment in China, Yu et al. found that PTSD was common in this group, and 40.2% of them showed PTSD symptoms, and nurses ranked first during this pandemic than other HCWs [13]. Jacobowitz et al. reported that the PTSD prevalence was almost equal among physicians and nurses, and Kim et al. also reported that the PTSD prevalence among HCWs was estimated to be above 50% [14, 15]. Overall, in HCWs with higher levels of exposure, arousal symptoms were more common, and there was a significant difference between people with PTSD and without PTSD in terms of sleep quality [16]. Considering that the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a huge burden on governments, organizations and various individuals, especially HCWs [17], who are in the frontline of fight against this critical situation, they consequently are at higher risk for psychological distress, especially PTSD and other mental health disorders [18]. Therefore, their mental health should be given special attention by managers, officials, and mental health planners to design targeted interventions to control mental crises in these people [19, 20].

Hence, the present study aimed to investigate the PTSD prevalence among the HCWs involved with COVID-19 treatment and the effective factors in the Military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The results of the present study can provide strong evidence that HCWs in both military and non-military hospitals need support and appropriate psychological interventions in the form of effective treatment models, including resilience strategies at the organizational and personal levels due to the stressful COVID-19 period to reduce and prevent the psychological effects of this pandemic, especially PTSD. Providing psychological resilience interventions for the front-line HCWs is one of the highest priorities during this pandemic. Also, the results of the present research can be an effective first step for management departments and policymakers in the field of mental health to plan for holding workshops and training seminars to train mental HCWs, such as workshops on stress management, resilience, etc.

Instruments and Methods

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional study, which was performed within the first two months of 2021 (fourth peak). The study population included all HCWs in the military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in Tehran. They were involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in the military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran since the end of 2017. The samples were selected using cluster random sampling among the HCWs working in three hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran, including Imam Reza or 501, Family, and Hajar (503) hospitals based on Cochran's sample size formula in epidemiological studies and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

It should be noted that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iran is reported to be about 25%. The sample size of the present study was estimated at 335 people. On the other hand, considering the possible 10% dropout, finally, a sample size of 356 people was included in the present study after obtaining the necessary permissions from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of the University of Medical Sciences. These participants were selected from HCWs working in three hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran, including Imam Reza or 501, Family, and Hajar (503) hospitals based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included: being an HCW in COVID-19 treatment since late 2019 and having the necessary motivation and desire to participate in the research.

The PTSD prevalence was investigated using the instruments as follows:

1) Researcher-made demographic characteristics questionnaire: This questionnaire contained questions about age, sex, education level, rank, years of work experience, type of job, duration of employment in COVID-19 treatment, etc.

2) PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview for DSM-5 (PSS-I-5): The first version of this scale, titled PSS-I-3, was developed in 1993 by FOA et al. in 2013 and was modified by Edna B. Foa and Sandy Capaldi as a semi-structured-and flexible interview based on the DSM-5 (PSS-I-5) to detect PTSD as well as assess the severity of symptoms to clinicians who were familiar with PTSD. When completing PSS-I-5, interviewers should relate the symptoms to a specific “target” stressful trauma; PSS-I-5 may be used to assess symptoms associated with any traumatic event. To validate the PTSD symptom rating, the interviewer must determine the time frame in which the symptoms are reported. This version of PSS-I-5 is only used for symptoms that have occurred in the last month. Theoretically, PSS-I-5 could be used to assess symptoms over longer and shorter periods, but the interview validity has not been investigated here. Ultimate severity is a combination of information according to the prevalence with which symptoms are experienced and the severity of symptoms when they are experienced. PSS-I-5 standardization and scoring help us achieve the most reliable results. PTSD is diagnosed by counting the number of confirmed symptoms (rank 1 or higher) in each cluster of symptoms. One intrusion symptom, one avoidance symptom, two cognition and mood symptoms, and two anxiety and arousal symptoms are required to meet the diagnostic criteria. The PTSD diagnosis also requires the presence of symptoms for more than a month (F) and significant clinical discomfort or disorder (G) [21]. Evidence from the PSS-I-5 evaluation in FOA et al.'s study in 2015 shows that the internal consistency of the study is high (0.89), and the test-retest reliability is 0.87. Also, the inter-rater reliability is high (0.98), and the inter-rater agreement for PTSD diagnosis is 0.84 [22].

To analyze the data at the descriptive level, descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were used. At the analytical level, Chi-square test were used. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26 software.

Findings

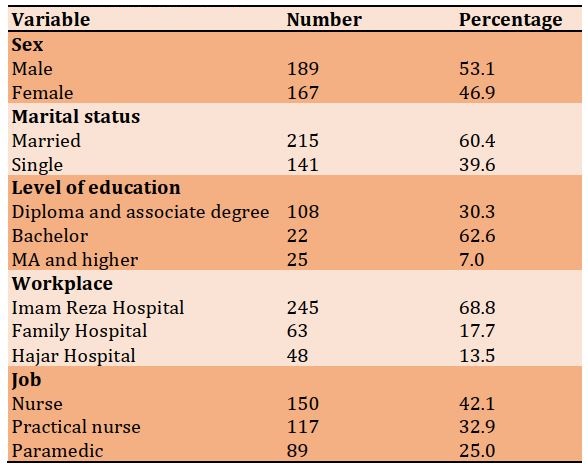

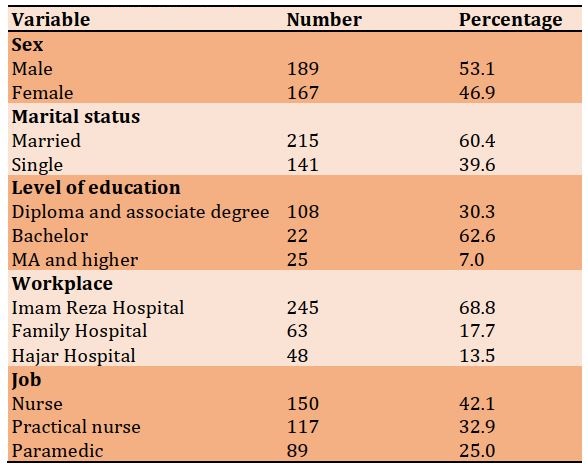

The mean age of the participants was 34.06±7.78 years. 189 participants were male, and 167 were female, of whom 39.6% of the HCWs were single and 60.4% were married. 245, 63, and 48 HCWs worked in Imam Reza Hospital, Family Hospital, and Hajar Hospital, respectively. 62.6% of participants had a bachelor's degree, and 7% of them had a master's degree or higher. 42.1% of HCWs were nurses, 32.9% were practical nurses, and 25% were paramedics (Table 1).

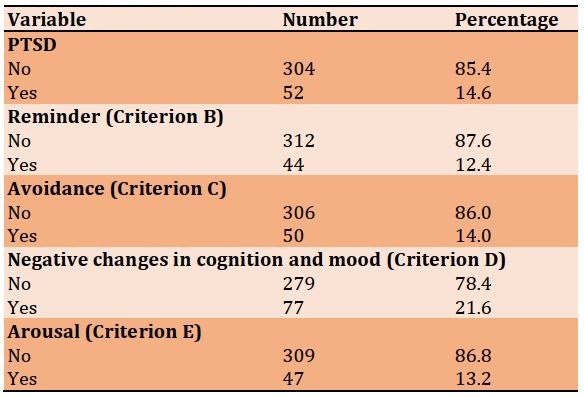

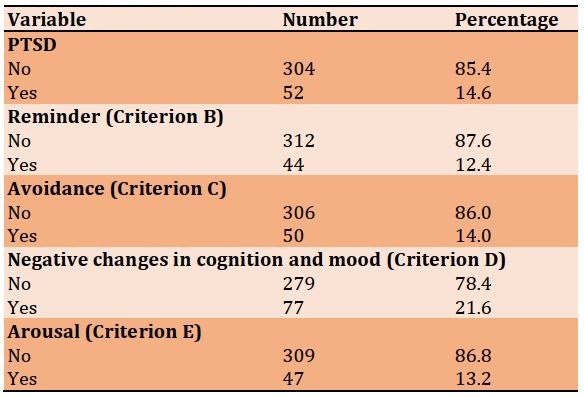

85.4% of the studied HCWs had no PTSD, and 14.6% had PTSD. 12.4% of the HCWs had criteria B (intrusion), 14% had criteria C (avoidance), 21.6% had criteria D (negative changes in cognition and mood), and 13.2% had criteria E (arousal) (Table 2).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of demographic characteristics of study participants (n=356)

Table 2) Frequency distribution of PTSD and its clusters in study participants (n=356)

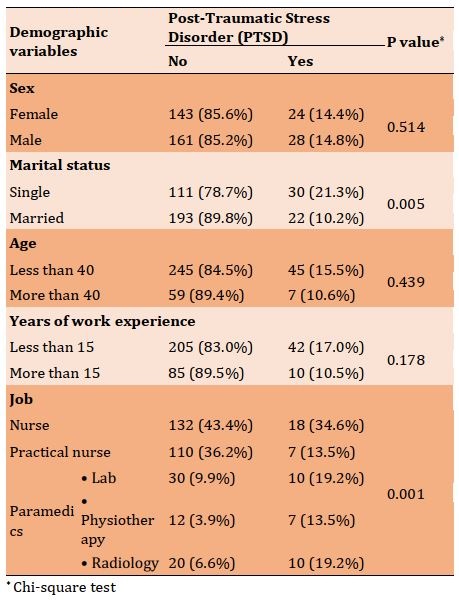

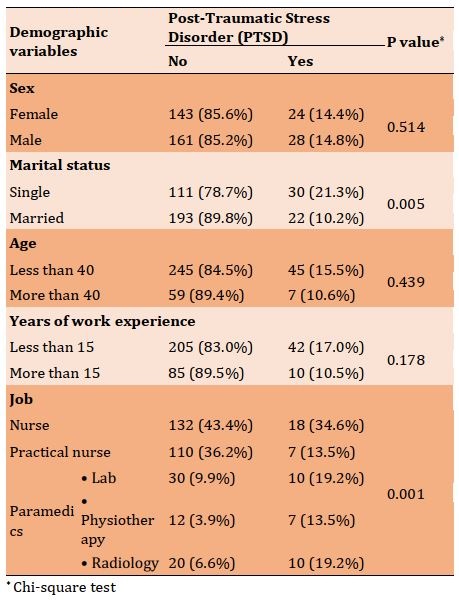

The most common clusters included negative changes in mood and cognition (21.6%), avoidance (14%), arousal (13.6%), and intrusion (12.4%), respectively. There was no significant difference in the PTSD of HCWs based on sex. There was no relationship between age and PTSD prevalence rate. There was no relationship between years of work experience and PTSD prevalence in the HCWs. But the PTSD prevalence rate in single people was higher than in married people. The PTSD incidence rate was higher in nurses; therefore, there was a relationship between the type of job and the PTSD incidence rate.

42.1%, 32.9%, and 25% of the HCWs were nurses, practical nurses, and paramedics, respectively. Also, concerning the D criterion (negative changes in cognition and mood), the PTSD prevalence rate among nurses, practical nurses, and paramedics was 20.7%, 9.4%, and 39.3%, respectively. An analytical comparison of the results showed a statistically significant difference in the PTSD rate based on the job variable in criterion D (Table 3).

Table 3) Comparison of the frequency distribution of PTSD in the HCWs based on demographic variables

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the PTSD prevalence among HCWs involved with COVID-19 and its effective factors in the military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran, within the first two months of 2021 (fourth peak).

According to previous studies, the PTSD incidence rate and lifetime prevalence among the general population is approximately between 1% and 9% [23] and about 4.6 to 7% among adults living in cities during the COVID-19 crisis [6]. The present study is consistent with the results of study by Wu et al. (PTSD prevalence=10%) [24], but inconsistent with studies by Johnson et al. [12], Zhu et al. [16], Robinson [18], and Kim Lee et al. [5] that reported that the PTSD prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic was higher than the present study (25% and 55.1%). The present study is also inconsistent with the study by Sun et al. [9], Liu et al. [25], Si et al. [23], and Yin et al. [26] that reported lower PTSD prevalence rates during the COVID-19 pandemic as compared the present study (3.8% and 8.1%).

PTSD occurs after a severe traumatic event [14]. There is no doubt that HCWs are more vulnerable than other people due to the nature of the job and the need to intervene in critical situations. HCWs become stressed and feel lonely because they are more likely to develop COVID-19 than the rest of society, and due to the length of quarantine, lack of space for physical activity, stress from limited social interactions, and anxiety about fear of transmitting the infection to family members. Therefore, it is necessary to pay more attention to the mental health of these people. This suggests that social isolation can lead to negative emotions [3]. The inconsistency may be due to high working hours, different organizational structures in different countries, differences in the selection of people, workload, social and organizational support. Also, the severity of the trauma and its duration (being in the hospital) increase the severity of PTSD symptoms. It is also possible that this rate may increase in the study population in the future.

The results of the present study are inconsistent with studies by Safa et al. [13] and Yin et al. [26], where the prevalence of PTSD clusters during the COVID-19 pandemic was lower than in the present study.

The discrepancy between the present study and some studies in terms of PTSD prevalence may be attributed to the difference in the evaluation method and the type of tools used in the present study. In most of the mentioned studies, only the questionnaire was used, and no clinical interview was conducted, and diagnosis was made based on the scores of the questionnaires without considering the level of performance of the subject and without segregation of PTSD-related psychological symptoms. This makes it difficult to make an accurate diagnosis. Since a semi-structured interview that allows accurate diagnosis was used in the present study, the results can be more reliable.

According to the results of the semi-structured PSS-I-5 interview in the present study, negative changes in mood and cognition symptoms accounted for the highest prevalence in HCWs involved with COVID -19 treatment. It indicates that the COVID -19 pandemic causes changes in mood and cognition of the health care workers, which in turn indicates an increase in negative thoughts and a decrease in mood stability. One of the reasons for this increase is the possibility of being exposed to COVID-19 infection and the fear of death of oneself and relatives, which indicates that being separated from others can cause negative feelings. Among these people are HCWs who spent a lot of time away from their families and were in quarantine [12]. Hence, the World Health Organization (WHO) has replaced the term “social distance” with “physical distance” so that people do not feel lonely and isolated; because, according to previous studies, “loneliness” is a risk factor for death, and this change of term to some extent reduces the resulting negative emotions and anxiety.

Also, the analytical comparison of the results showed no not statistically significant difference in the PTSD prevalence among male and female HCWs (p<0.05). Therefore, there is no relationship between sex and PTSD prevalence in HCWs, which was consistent with the study by Safa et al. [13] and Narimani et al. [14], and inconsistent with the study by Karimi et al. [3], Liu et al. [4], Sun et al. [9] Kessler et al. [10], and Yin et al. [26].

The relative equality of women and men in the face of stressful situations in the present study, which is inconsistent with other relevant studies, can indicate that female participants of the present study have become more adaptable in recent years due to various problems such as war, earthquakes, economic crises, etc. and do not necessarily react more severely than men in the face of crises such as the COVID -19 pandemic.

The results based on marital variables showed that the PTSD prevalence in single people is higher than in married people, which was consistent with studies by Safa et al. [13] and Narimani et al. [14]. This suggests that social relationships are a preventative factor for PTSD and that loneliness increases the risk of developing PTSD and is regarded as a risk factor for developing PTSD in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, where many people are quarantined. It means the lack of social support (for example, spouse, family, friends, etc.) after a traumatic event or the persistent life stresses such as unemployment, financial pressures, disabilities etc., are among other factors influencing the emergence of this disorder.

The results based on the years of work experience also showed that the PTSD prevalence in the HCWs with less and more than 15 years of work experience is almost the same. Also, concerning the job variable, the results showed that PTSD prevalence is higher in nurses. Therefore, there was a relationship between the type of job and PTSD prevalence.

Limitations

- Because the study population included the medical staff of three Army hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Tehran, therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results of this research to the military treatment staff involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in other hospitals in the cities and other medical teams.

- Because the study population included the medical staff of three Army hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Tehran, therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results of this research to the non-military treatment staff involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in other hospitals in the cities and other medical teams.

Suggestions

- To know about the generalizability of the findings, it is suggested that the present research should be repeated in a larger sample size of the medical staff that works in army hospitals of other cities of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- To know about the generalizability of the findings, it is suggested that the present research should be repeated in a larger sample size of the treatment staff of other non-military hospitals in different cities of the country.

- It is suggested that the present study be conducted as a longitudinal study a few months after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and to evaluate the prevalence of delayed or chronic PTSD and job burnout.

- It is suggested that the present study be conducted jointly on the medical staff involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in other countries to obtain an accurate global estimate of the prevalence of PTSD among them.

- It is suggested to investigate the prevalence of other psychological disorders (depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, etc.) among the medical staff who provide healthcare services to COVID-19 patients.

- It is suggested to investigate the prevalence of PTSD among the recovered COVID-19 cases. The study group should not be only the medical staff, and other people should also be investigated.

Conclusion

COVID-19 disease can lead to serious psychological problems, especially in front-line medical treatment, and the serious spread of traumatic psychiatric symptoms in the current situation can lead to damage to the health system. The presence of PTSD and burnout in the HCWs should be considered an important factor affecting the health and performance of HCWs. While efforts are needed in many areas during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also imperative that time and money be spent on improving the mental health of at-risk HCWs as well as society as a whole.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the administration of the hospital, the respected HCWs, and the dear professors for their unreserved efforts and cooperation in the present study.

Ethical Permission: To observe ethical considerations, informed consent was first obtained, and the research objectives were explained, and participants were assured that their information would remain confidential. Confidentiality of personal information was observed by coding the questionnaires. Completion of the questionnaires and study participation were voluntary. The present research project was approved by the Faculty of Medicine of the Military University of Medical Sciences with the code of ethics in research IR.AJAMUS.REC.1399.162 on November 15, 2020.

Conflict of Interests: The authors state that there is no conflict of interest in the present study.

Authors’ Contribution:

Keyhani A (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (25%); Rahnejat AM (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Dabaghi P (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%); Taghva A (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (15%); Ebrahemi MR (Fifth Author), Discussion Writer (15%); Nezami Asl A (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer (10%)

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any university or research center.

At the end of December 2019, a new infectious disease caused by a new coronavirus was reported in Wuhan, China, and officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic poses unprecedented challenges to the healthcare system worldwide. The Cable News Network (CNN) has compared the impact of this pandemic on civilizations with World War II [2]. In this regard, unfortunately, this virus has infected Iran, like other countries. One of the characteristics of this disease is its rapid transmission, which endangers the mental health status of people at different levels of society [3-5]. In this regard, there is strong evidence that these people are prone to the symptoms of psychological disorders [6]. Anxiety, fear, depression, labeling, avoidance behaviors, irritability, sleep disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), marital conflicts, dependence on online networks, etc., are the most common problems and mental illnesses during the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. Findings from various studies show high COVID-19 infection among Healthcare Workers (HCWs) during the outbreak. In this regard, Wu and McGoogan found that the COVID-19 infection rate among HCWs is 3.8% [8]. Therefore, considering this high exposure, these conditions have created unprecedented challenges for healthcare systems that include uncertainty about the severity, duration, and effects of the crisis, concerns about the level of preparedness in personal and public healthcare organizations, inadequate personal protective equipment and other required medical equipment, and potential threats to for transmission of the infection to HCWs, their loved ones and colleagues [9, 10]. These conditions cause a high level of fear and anxiety in the short run and put HCWs at risk for persistent stress syndromes, professional burnout, and subclinical mental health symptom in the long run [11]. According to the results of many studies, PTSD is one of the most common disorders among HCWs during a crisis. In a study of PTSD symptoms among HCWs and public service providers during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Norway, Johnson et al. concluded that 28.9% of the HCWs had clinical and subclinical PTSD symptoms, and symptoms were significantly higher in those who worked directly with patients [12]. In a cross-sectional study of 863 HCWs involved with COVID-19 treatment in China, Yu et al. found that PTSD was common in this group, and 40.2% of them showed PTSD symptoms, and nurses ranked first during this pandemic than other HCWs [13]. Jacobowitz et al. reported that the PTSD prevalence was almost equal among physicians and nurses, and Kim et al. also reported that the PTSD prevalence among HCWs was estimated to be above 50% [14, 15]. Overall, in HCWs with higher levels of exposure, arousal symptoms were more common, and there was a significant difference between people with PTSD and without PTSD in terms of sleep quality [16]. Considering that the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a huge burden on governments, organizations and various individuals, especially HCWs [17], who are in the frontline of fight against this critical situation, they consequently are at higher risk for psychological distress, especially PTSD and other mental health disorders [18]. Therefore, their mental health should be given special attention by managers, officials, and mental health planners to design targeted interventions to control mental crises in these people [19, 20].

Hence, the present study aimed to investigate the PTSD prevalence among the HCWs involved with COVID-19 treatment and the effective factors in the Military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The results of the present study can provide strong evidence that HCWs in both military and non-military hospitals need support and appropriate psychological interventions in the form of effective treatment models, including resilience strategies at the organizational and personal levels due to the stressful COVID-19 period to reduce and prevent the psychological effects of this pandemic, especially PTSD. Providing psychological resilience interventions for the front-line HCWs is one of the highest priorities during this pandemic. Also, the results of the present research can be an effective first step for management departments and policymakers in the field of mental health to plan for holding workshops and training seminars to train mental HCWs, such as workshops on stress management, resilience, etc.

Instruments and Methods

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional study, which was performed within the first two months of 2021 (fourth peak). The study population included all HCWs in the military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in Tehran. They were involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in the military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran since the end of 2017. The samples were selected using cluster random sampling among the HCWs working in three hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran, including Imam Reza or 501, Family, and Hajar (503) hospitals based on Cochran's sample size formula in epidemiological studies and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

It should be noted that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iran is reported to be about 25%. The sample size of the present study was estimated at 335 people. On the other hand, considering the possible 10% dropout, finally, a sample size of 356 people was included in the present study after obtaining the necessary permissions from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of the University of Medical Sciences. These participants were selected from HCWs working in three hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran, including Imam Reza or 501, Family, and Hajar (503) hospitals based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included: being an HCW in COVID-19 treatment since late 2019 and having the necessary motivation and desire to participate in the research.

The PTSD prevalence was investigated using the instruments as follows:

1) Researcher-made demographic characteristics questionnaire: This questionnaire contained questions about age, sex, education level, rank, years of work experience, type of job, duration of employment in COVID-19 treatment, etc.

2) PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview for DSM-5 (PSS-I-5): The first version of this scale, titled PSS-I-3, was developed in 1993 by FOA et al. in 2013 and was modified by Edna B. Foa and Sandy Capaldi as a semi-structured-and flexible interview based on the DSM-5 (PSS-I-5) to detect PTSD as well as assess the severity of symptoms to clinicians who were familiar with PTSD. When completing PSS-I-5, interviewers should relate the symptoms to a specific “target” stressful trauma; PSS-I-5 may be used to assess symptoms associated with any traumatic event. To validate the PTSD symptom rating, the interviewer must determine the time frame in which the symptoms are reported. This version of PSS-I-5 is only used for symptoms that have occurred in the last month. Theoretically, PSS-I-5 could be used to assess symptoms over longer and shorter periods, but the interview validity has not been investigated here. Ultimate severity is a combination of information according to the prevalence with which symptoms are experienced and the severity of symptoms when they are experienced. PSS-I-5 standardization and scoring help us achieve the most reliable results. PTSD is diagnosed by counting the number of confirmed symptoms (rank 1 or higher) in each cluster of symptoms. One intrusion symptom, one avoidance symptom, two cognition and mood symptoms, and two anxiety and arousal symptoms are required to meet the diagnostic criteria. The PTSD diagnosis also requires the presence of symptoms for more than a month (F) and significant clinical discomfort or disorder (G) [21]. Evidence from the PSS-I-5 evaluation in FOA et al.'s study in 2015 shows that the internal consistency of the study is high (0.89), and the test-retest reliability is 0.87. Also, the inter-rater reliability is high (0.98), and the inter-rater agreement for PTSD diagnosis is 0.84 [22].

To analyze the data at the descriptive level, descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were used. At the analytical level, Chi-square test were used. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26 software.

Findings

The mean age of the participants was 34.06±7.78 years. 189 participants were male, and 167 were female, of whom 39.6% of the HCWs were single and 60.4% were married. 245, 63, and 48 HCWs worked in Imam Reza Hospital, Family Hospital, and Hajar Hospital, respectively. 62.6% of participants had a bachelor's degree, and 7% of them had a master's degree or higher. 42.1% of HCWs were nurses, 32.9% were practical nurses, and 25% were paramedics (Table 1).

85.4% of the studied HCWs had no PTSD, and 14.6% had PTSD. 12.4% of the HCWs had criteria B (intrusion), 14% had criteria C (avoidance), 21.6% had criteria D (negative changes in cognition and mood), and 13.2% had criteria E (arousal) (Table 2).

Table 1) Frequency distribution of demographic characteristics of study participants (n=356)

Table 2) Frequency distribution of PTSD and its clusters in study participants (n=356)

The most common clusters included negative changes in mood and cognition (21.6%), avoidance (14%), arousal (13.6%), and intrusion (12.4%), respectively. There was no significant difference in the PTSD of HCWs based on sex. There was no relationship between age and PTSD prevalence rate. There was no relationship between years of work experience and PTSD prevalence in the HCWs. But the PTSD prevalence rate in single people was higher than in married people. The PTSD incidence rate was higher in nurses; therefore, there was a relationship between the type of job and the PTSD incidence rate.

42.1%, 32.9%, and 25% of the HCWs were nurses, practical nurses, and paramedics, respectively. Also, concerning the D criterion (negative changes in cognition and mood), the PTSD prevalence rate among nurses, practical nurses, and paramedics was 20.7%, 9.4%, and 39.3%, respectively. An analytical comparison of the results showed a statistically significant difference in the PTSD rate based on the job variable in criterion D (Table 3).

Table 3) Comparison of the frequency distribution of PTSD in the HCWs based on demographic variables

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the PTSD prevalence among HCWs involved with COVID-19 and its effective factors in the military hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Tehran, within the first two months of 2021 (fourth peak).

According to previous studies, the PTSD incidence rate and lifetime prevalence among the general population is approximately between 1% and 9% [23] and about 4.6 to 7% among adults living in cities during the COVID-19 crisis [6]. The present study is consistent with the results of study by Wu et al. (PTSD prevalence=10%) [24], but inconsistent with studies by Johnson et al. [12], Zhu et al. [16], Robinson [18], and Kim Lee et al. [5] that reported that the PTSD prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic was higher than the present study (25% and 55.1%). The present study is also inconsistent with the study by Sun et al. [9], Liu et al. [25], Si et al. [23], and Yin et al. [26] that reported lower PTSD prevalence rates during the COVID-19 pandemic as compared the present study (3.8% and 8.1%).

PTSD occurs after a severe traumatic event [14]. There is no doubt that HCWs are more vulnerable than other people due to the nature of the job and the need to intervene in critical situations. HCWs become stressed and feel lonely because they are more likely to develop COVID-19 than the rest of society, and due to the length of quarantine, lack of space for physical activity, stress from limited social interactions, and anxiety about fear of transmitting the infection to family members. Therefore, it is necessary to pay more attention to the mental health of these people. This suggests that social isolation can lead to negative emotions [3]. The inconsistency may be due to high working hours, different organizational structures in different countries, differences in the selection of people, workload, social and organizational support. Also, the severity of the trauma and its duration (being in the hospital) increase the severity of PTSD symptoms. It is also possible that this rate may increase in the study population in the future.

The results of the present study are inconsistent with studies by Safa et al. [13] and Yin et al. [26], where the prevalence of PTSD clusters during the COVID-19 pandemic was lower than in the present study.

The discrepancy between the present study and some studies in terms of PTSD prevalence may be attributed to the difference in the evaluation method and the type of tools used in the present study. In most of the mentioned studies, only the questionnaire was used, and no clinical interview was conducted, and diagnosis was made based on the scores of the questionnaires without considering the level of performance of the subject and without segregation of PTSD-related psychological symptoms. This makes it difficult to make an accurate diagnosis. Since a semi-structured interview that allows accurate diagnosis was used in the present study, the results can be more reliable.

According to the results of the semi-structured PSS-I-5 interview in the present study, negative changes in mood and cognition symptoms accounted for the highest prevalence in HCWs involved with COVID -19 treatment. It indicates that the COVID -19 pandemic causes changes in mood and cognition of the health care workers, which in turn indicates an increase in negative thoughts and a decrease in mood stability. One of the reasons for this increase is the possibility of being exposed to COVID-19 infection and the fear of death of oneself and relatives, which indicates that being separated from others can cause negative feelings. Among these people are HCWs who spent a lot of time away from their families and were in quarantine [12]. Hence, the World Health Organization (WHO) has replaced the term “social distance” with “physical distance” so that people do not feel lonely and isolated; because, according to previous studies, “loneliness” is a risk factor for death, and this change of term to some extent reduces the resulting negative emotions and anxiety.

Also, the analytical comparison of the results showed no not statistically significant difference in the PTSD prevalence among male and female HCWs (p<0.05). Therefore, there is no relationship between sex and PTSD prevalence in HCWs, which was consistent with the study by Safa et al. [13] and Narimani et al. [14], and inconsistent with the study by Karimi et al. [3], Liu et al. [4], Sun et al. [9] Kessler et al. [10], and Yin et al. [26].

The relative equality of women and men in the face of stressful situations in the present study, which is inconsistent with other relevant studies, can indicate that female participants of the present study have become more adaptable in recent years due to various problems such as war, earthquakes, economic crises, etc. and do not necessarily react more severely than men in the face of crises such as the COVID -19 pandemic.

The results based on marital variables showed that the PTSD prevalence in single people is higher than in married people, which was consistent with studies by Safa et al. [13] and Narimani et al. [14]. This suggests that social relationships are a preventative factor for PTSD and that loneliness increases the risk of developing PTSD and is regarded as a risk factor for developing PTSD in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, where many people are quarantined. It means the lack of social support (for example, spouse, family, friends, etc.) after a traumatic event or the persistent life stresses such as unemployment, financial pressures, disabilities etc., are among other factors influencing the emergence of this disorder.

The results based on the years of work experience also showed that the PTSD prevalence in the HCWs with less and more than 15 years of work experience is almost the same. Also, concerning the job variable, the results showed that PTSD prevalence is higher in nurses. Therefore, there was a relationship between the type of job and PTSD prevalence.

Limitations

- Because the study population included the medical staff of three Army hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Tehran, therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results of this research to the military treatment staff involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in other hospitals in the cities and other medical teams.

- Because the study population included the medical staff of three Army hospitals of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Tehran, therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results of this research to the non-military treatment staff involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in other hospitals in the cities and other medical teams.

Suggestions

- To know about the generalizability of the findings, it is suggested that the present research should be repeated in a larger sample size of the medical staff that works in army hospitals of other cities of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- To know about the generalizability of the findings, it is suggested that the present research should be repeated in a larger sample size of the treatment staff of other non-military hospitals in different cities of the country.

- It is suggested that the present study be conducted as a longitudinal study a few months after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and to evaluate the prevalence of delayed or chronic PTSD and job burnout.

- It is suggested that the present study be conducted jointly on the medical staff involved in the treatment of COVID-19 in other countries to obtain an accurate global estimate of the prevalence of PTSD among them.

- It is suggested to investigate the prevalence of other psychological disorders (depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, etc.) among the medical staff who provide healthcare services to COVID-19 patients.

- It is suggested to investigate the prevalence of PTSD among the recovered COVID-19 cases. The study group should not be only the medical staff, and other people should also be investigated.

Conclusion

COVID-19 disease can lead to serious psychological problems, especially in front-line medical treatment, and the serious spread of traumatic psychiatric symptoms in the current situation can lead to damage to the health system. The presence of PTSD and burnout in the HCWs should be considered an important factor affecting the health and performance of HCWs. While efforts are needed in many areas during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also imperative that time and money be spent on improving the mental health of at-risk HCWs as well as society as a whole.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the administration of the hospital, the respected HCWs, and the dear professors for their unreserved efforts and cooperation in the present study.

Ethical Permission: To observe ethical considerations, informed consent was first obtained, and the research objectives were explained, and participants were assured that their information would remain confidential. Confidentiality of personal information was observed by coding the questionnaires. Completion of the questionnaires and study participation were voluntary. The present research project was approved by the Faculty of Medicine of the Military University of Medical Sciences with the code of ethics in research IR.AJAMUS.REC.1399.162 on November 15, 2020.

Conflict of Interests: The authors state that there is no conflict of interest in the present study.

Authors’ Contribution:

Keyhani A (First Author), Methodologist/Main Researcher (25%); Rahnejat AM (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Discussion Writer (20%); Dabaghi P (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Assistant Researcher (15%); Taghva A (Fourth Author), Statistical Analyst (15%); Ebrahemi MR (Fifth Author), Discussion Writer (15%); Nezami Asl A (Sixth Author), Introduction Writer (10%)

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any university or research center.

Keywords:

References

1. Shahyad S, Mohammadi MT. Psychological impacts of Covid-19 outbreak on mental health status of society individuals: a narrative review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(2):184-92. [Persian] [Link]

2. Restauri N, Sheridan AD. Burnout and posttraumatic stress disorder in the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic: intersection, impact, and interventions. J Am Coll of Radiol. 2020;17(7):921-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.021]

3. Karimi L, Khalili R, Sirati Nir M. Prevalence of various psychological disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic: systematic review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(6):648-62. [Persian] [Link]

4. Liu X, Na RS, Bi ZQ. Challenges to prevent and control the outbreak of novel coronavirus pneumonia (Covid-19). Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(7):994-7. [Chinese] [Link]

5. Li S, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhao N, Zhu T. The impact of Covid-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active Weibo users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2032. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17062032]

6. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923921. [Link] [DOI:10.12659/MSM.923921]

7. Rahnedjat AM. The role of thought control strategies on the symptoms of chronic post-traumatic stress disorders caused by war. Int J Behav Sci. 2015;8(4):347-54. [Persian] [Link]

8. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.2648]

9. Sun L, Sun Z, Wu L, Zhu Z, Zhang F, Shang Z, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of acute posttraumatic stress symptoms during the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. MedRxiv. 2020:1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1101/2020.03.06.20032425]

10. Shahed Hagh Ghadam H, Fathi Ashtiani A, Rahnejat AM, Ahmadi Tahour Soltani M, Taghva A, Ebrahimi MR, et al . Psychological Consequences and Interventions during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Narrative Review. J Mar Med. 2020;2(1):1-11. [Persian] [Link]

11. Rahnejat AM, Rabiei M, Salimi SH, Fathi Ashtiani A, Donyavi V, Mirzai J. Causal metacognitive model war-related chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2015;20(4):317-25. [Persian] [Link]

12. Johnson SU, Ebrahimi OV, Hoffart A. PTSD symptoms among health workers and public service providers during the Covid-19 outbreak. PloS One. 2020;15(10):e0241032. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0241032]

13. Safa M, Esmaeili Doulabinezhad S, Ghasem Boroujerdi F, Hajizadeh F, Mirabzadeh Ardakani B. Incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder after Covid-19 among medical staff of Masih Daneshvari Hospital. J Med Counc Iran. 2020;38(1):27-33. [Persian] [Link]

14. Ebrahimpour M, Azzizadeh Forouzi M, Tirgari B. The relationship between post-traumatic stress symptoms and professional quality of life in psychiatric nurses. Hayat. 2017;22(4):312-24. [Persian] [Link]

15. Kim Y, Seo E, Seo Y, Dee V, Hong E. Effects of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus on post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout among registered nurses in South Korea. Int J Healthcare. 2018;4(2):27-33. [Link] [DOI:10.5430/ijh.v4n2p27]

16. Zhu Z, Xu S, Wang H, Liu Z, Wu J, Li G, et al. Covid-19 in Wuhan: immediate psychological impact on 5062 health workers. MedRxiv. 2020. [Link] [DOI:10.1101/2020.02.20.20025338]

17. World Health Organization. WHO timeline-Covid-19 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2022 May 01]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19. [Link]

18. Mehrad A. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) effect of coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic and role of emotional intelligence. J Soc Sci Res. 2020;15:185-90. [Link] [DOI:10.24297/jssr.v15i.8750]

19. Mirkazehi-Rigi Z, Dadpisheh S, Sheikhi F, Baloch V, Kalkali S. Challenges and solutions to deal with Covid-19 from the point of view of physicians and nurses in southern Sistan and Baluchistan (Iranshahr). J Mil Med. 2020;22(6):599-606. [Persian] [Link]

20. Safari M, Vahidian-Azimi A, Mahmoudi H. Self-protection experiences of nurses while caring for Covid-19 patients. J Mil Med. 2020;22(6):570-9. [Persian] [Link]

21. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Rezaei F, translator. Fifth Edition. Tehran: Arjmand; 2016. [Persian] [Link]

22. Karimi M, Rahnejat AM, Dabaghi P, Taghva A, Majdian M, Donyavi V, et al. The psychometric properties of the post-traumatic stress disorder symptom scale-interview based on DSM-5, in military personnel participated in warfare. Iran J War Public Health. 2020;12(47):115-24. [Link] [DOI:10.29252/ijwph.12.2.115]

23. Si MY, Su XY, Jiang Y, Wang WJ, Gu XF, Ma L, et al. Psychological impact of Covid-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):1-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0]

24. Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302-11. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/070674370905400504]

25. Liu SL, Wang ZG, Xie HY, Liu AA, Lamb DC, Pang DW. Single-virus tracking: from imaging methodologies to virological applications. Chem Rev. 2020;120(3):1936-79. [Link] [DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00692]

26. Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, Ni X, Deng X, Jia Y, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27(3):384-95. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2477]