Volume 13, Issue 3 (2021)

Iran J War Public Health 2021, 13(3): 203-208 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/08/21 | Accepted: 2021/12/8 | Published: 2021/12/25

Received: 2021/08/21 | Accepted: 2021/12/8 | Published: 2021/12/25

How to cite this article

Sabzi Khoshnami M, Javadi S, Noruzi S, Vahdani B, Tahmasebi S, Azari Arghun T et al . Developing an Inter-Organizational Guide of Psychosocial Support for the Survivors and Victims’ Families of COVID-19. Iran J War Public Health 2021; 13 (3) :203-208

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-997-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-997-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

M. Sabzi Khoshnami1, S.M.H. Javadi1, S. Noruzi *2, B. Vahdani3, S. Tahmasebi4, T. Azari Arghun5, S. Sayar6

1- Department of Social Work, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Social Work, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

3- Department of Psychiatry, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

4- Preschool Department, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- Department of Social Work, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

6- Department of Sociology, North Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Social Work, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

3- Department of Psychiatry, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

4- Preschool Department, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- Department of Social Work, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

6- Department of Sociology, North Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (589 Views)

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization's epidemiology report, as of July 30, 2021, one hundred and ninety-six million people have been infected with the COVID-19 virus worldwide, of which four million one hundred and ninety-eight thousand people have died. That is, about 2 out of every 100 people in the world die from Covid-19, which is equivalent to 4 in Iran [1]. From the time of diagnosis, it usually takes less than two weeks for the patients to die, during which the companions may not be able to see the patient, so it is natural that family members of the deceased may not be able to adjust themselves to the grief [2].

Grief is a set of feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that people experience in the face of loss or the threat of loss. While mourning is natural and pervasive in all human societies, the expression of grief is different among individuals [3]. Grief is not considered a disorder and 6 months after the loss, the symptoms of mourning decrease [4]. About 10 percent of the bereaved also experience complex grief, which is called morbid or long-term grief [5]. This estimate is higher during crises [6]. Given the striking similarities between natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., high mortality, many secondary stressors, severe social deprivation), similar patterns in spiritual, mental, and social health symptoms are predicted among people affected by COVID-19 [7]. As spiritual and psychosocial health problems increase in natural disasters such as pandemics [8], less attention is given to the responses to intense grief and long and complicated mourning.

Complicated grief occurs when certain aspects of natural grief are distorted or exacerbated, such as failure to perform current cultural events, leading to psychosocial dysfunction [9]. The cause of death has always been recognized as a factor in the grief response, and there is evidence that sudden death leads to a more severe reaction in survivors [10].

The prevalence of complex and long-term grief depends on the circumstances of death, age range, and other factors. Experiencing long-term grief was reported in parents (between 30 and 50%). In another study of unexpected family deaths, survivors experience between 5 and 20 percent of long-term reactions and complex grief [11]. The prevalence of complex grief is higher in people with depression, adaptation problems, and psychiatric patients. In an Iranian sample with specific socio-economic characteristics, the prevalence of complex grief was estimated to be 3.73% [12]. In the case of the COVID_19 pandemic, it is not possible to hold a mourning ceremony to prevent the disease, and even the burial of the deceased is done with the least possible number of people [13]. In the current situation, all social support is taken away from the survivors and they find themselves alone. Self-isolation and lack of communication with the environment intensify and prolong the grieving process [13, 14]. Challenges in performing new social roles and responsibilities (such as finances, parenting, supervision) and losing one's identity can lead to prolonged grief and complex mourning [15]. The process of grief can be influenced by social systems, media coverage, and people's attitudes towards the type of death [7]. Perceived social support is one of the factors that help increase recovery in the grieving process, especially in complex grief. In this situation, the person feels loved and valued and belongs to a network of communication [16]. Given the lack of research on grief after the global outbreak of the virus, it can be argued that the Covid-19 virus may increase the complex mourning in the world [17]. Family and social consequences of grief include decreased social cohesion, increased tendency to isolation, and weakened interpersonal communication skills. People also become cold and unmotivated about healthy behaviors [18].

As mentioned before, in the current context, in addition to the psychological and societal pressures on the families and survivors of the Covid-19 deceased, the loss of a guardian, lack of income, and economic pressures could exacerbate their problems. Some families have lost more than one loved one and remaining family members were under quarantine, supporting programs are needed in addition to grief counseling. As long as communities face this problem, having an indigenous program and model for the social rehabilitation of the families of the deceased can alleviate the problems caused by Covid-19 deaths. Therefore, this study aimed to design and develop inter-organizational psychosocial support for the family and survivors of the deceased Covid-19 and to pay attention to the inter-organizational aspects of providing psychosocial support.

Participants and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted in 2021. At first, all accessible search engines and databases, especially those for systematic reviews and guidelines were searched. Then, several focus group discussions and rounds of Delphi were carried out with 35 experts, who were selected purposively in the first phase.

The literature review was performed on databases that serve as references of guidelines and protocols for social workers and psychologists, such as the International Social Welfare Federation (FASW) website, the National Association of Social Workers, United States Social Network (NASW) and the International Network of Guidelines (GIN). Also, the databases of PubMed, Scopus, ISI (Web of sciences), the database of the World Health Organization, and PsychINFO were studied to review the articles from 2000 to 2020. The following keywords were searched: Psycho-social support in COVID-19, Psycho-social support, Psycho-social support for the family of the deceased, Psycho-social support in grief.

Extracted data were collected through the Delphi Method with 25 social workers and clients working at hospitals in Iran as well as experts and scholars in the field of mental health, experts of Welfare Organizations, Red Crescent center, Imam Khomeini Relief Committee, and Tehran Municipality. Inclusion criteria for forming the Delphi group were: having at least a master's degree in social work and psychology (general and clinical), people with a degree in psychiatry, having at least two years of working experience in health care centers, and willingness to collaborate in this study.

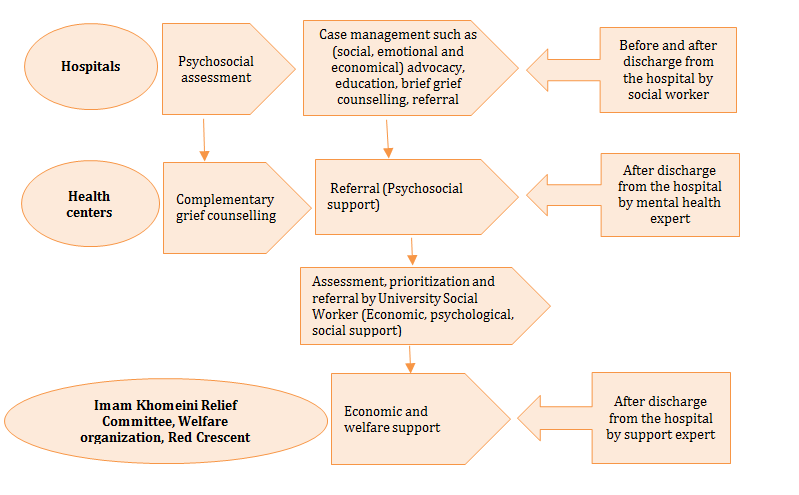

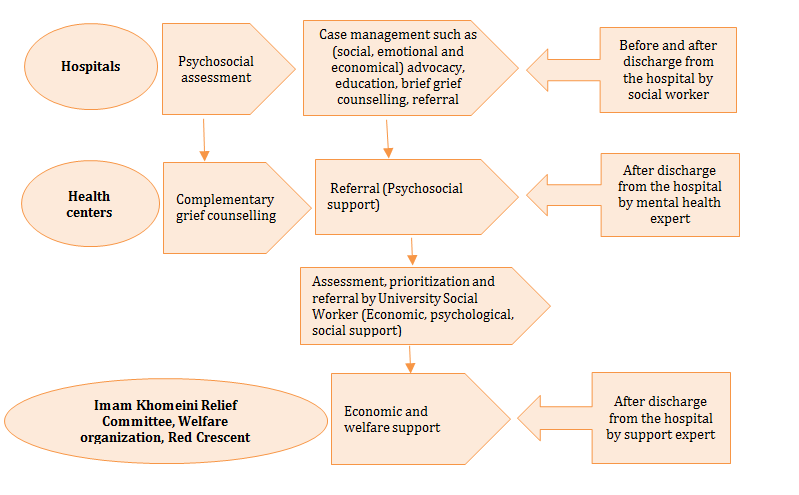

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Ministry of Health. In all stages of the study, all ethical issues regarding review and qualitative research have been observed. Due to time constraints and critical conditions, the Delphi technique was performed in three rounds. In the Delphi method, a questionnaire was prepared with the help of research team members, and questions were asked about psychosocial support to crisis survivors and the services of welfare organizations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were asked to return their written feedbacks in 48 hours. The results were then reviewed, summarized, and returned to Delphi members. The results of the second round were summarized and the resulting process was shared and discussed in a focus group discussion session (Chart 1).

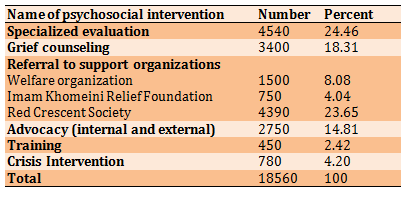

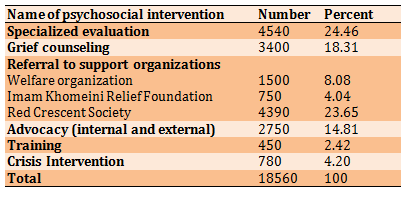

The findings of the Delphi method and resource review were examined using a focus group discussion method. Ten experts participated in three virtual sessions and one face-to-face session. A panel of experts was used to evaluate the validity and reliability of the interventions. The panel consisted of 5 social experts with work experience and familiarity with support organizations. The interventions were first piloted for two weeks in five cities (Tehran, Borujerd, Esfahan, Mashhad, and Qom) and then for six months (April 15-September 20) in all provinces of Iran (Table 1).

Table 1) Psychosocial interventions for the survivors of the deceased Covid-19 (Total number of deceased=52670)

Out of the 18560 households of deceased members, 4540 people were evaluated. The majority of them (24.5%) referred to Red Crescent Society and about 18.3% received grief counseling the least common type of intervention was training (2.42%).

Chart 1) Delphi results

Findings

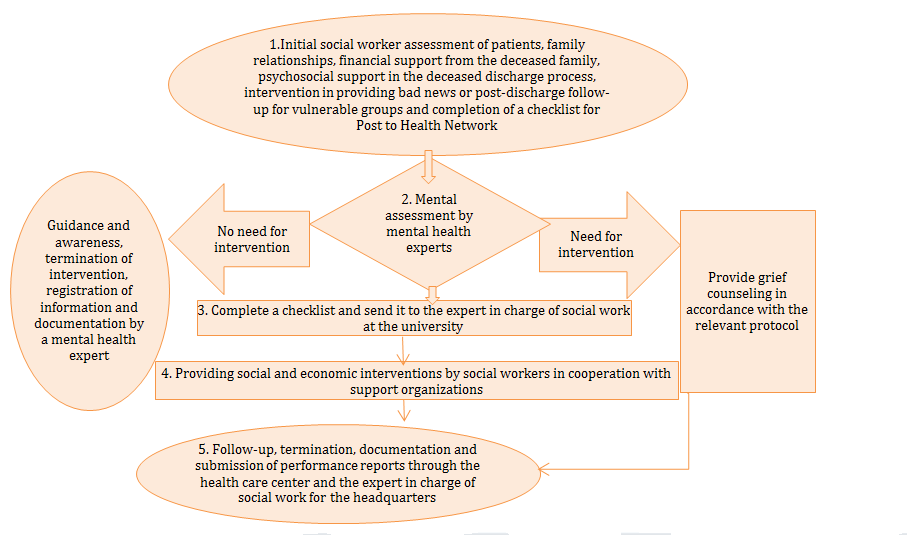

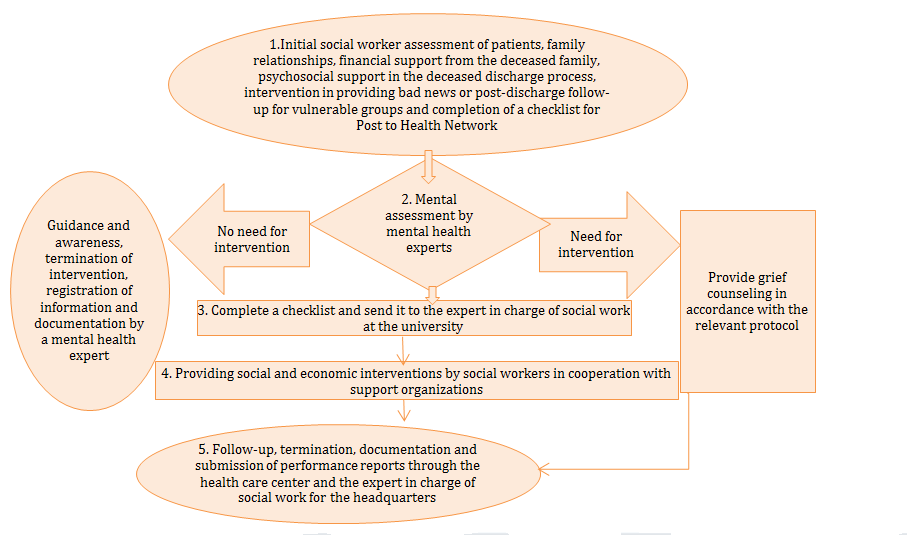

After reviewing the sources, Delphi, and group discussion, a process with 5 steps was designed, which are: Initial social worker assessment, mental assessment by mental health experts, complete a checklist and send it to the expert in charge of social work at the university, providing social and economic interventions by social workers in cooperation with support organizations and finally follow-up, termination, and documentation (according to figure 1). The process of psychosocial support begins with an initial assessment in the hospitals. Patient evaluation includes case studies, family contact, and information from the treatment team about the patient's condition. The social worker provided the context for family members to communicate with the patient through observing social distance or virtual communication. After the death of the patient, the unpleasant news was reported to the family by the principles. In order to communicate with the survivors of the deceased, a list of the deceased and their family contact numbers were prepared by social workers and were sent to the mental health experts. The target groups were the survivors and families of the deceased Covid-19 patients who could receive psychosocial support according to the outlined process. Inclusion criteria are: the family of the deceased Corona, need to receive financial support and consulting services, Willingness to receive services, and Collaborate with the hospital social worker.

In the second stage, a mental assessment was performed by a mental health expert, and within 7 to 14 days after the death, the survivors were contacted by phone, and, while expressing sympathy, the purpose of the call was explained. If the family did not need specialized interventions, the intervention ended after informing and providing the necessary guidance. Grief counseling was provided for the family members who expressed the need for counseling. It was done in four stages of flexible event evaluation and increasing understanding of loss, coping with grief and mourning, retrieval and evaluation of treatment. People are referred to a psychiatrist if they need medication and emergency interventions. Given the role of each of the participating organizations in the protocol and the tasks assigned to them in Delphi, a checklist was designed to examine how to provide services quantitatively and qualitatively. Checklists were completed daily and sent to the university's social work expert for evaluation and referral to support organizations. The third step was to evaluate the checklist and plan for referrals and follow-up. The checklist includes the type, quantity, and quality of services provided. The final step includes follow-up, conclusion, documenting, and reporting performance. To prevent the spread of disease, follow-ups were done only by phone calls. The purpose of the follow-up was to review the receipt of services and support to which the client has been referred for a reason. If the desired service and support were not received by the client, the follow-up continued until the desired result was achieved.

Figure 1) Inter-organizational psychosocial support for the families and survivors of COVID-19 deceased

According to the World Health Organization's epidemiology report, as of July 30, 2021, one hundred and ninety-six million people have been infected with the COVID-19 virus worldwide, of which four million one hundred and ninety-eight thousand people have died. That is, about 2 out of every 100 people in the world die from Covid-19, which is equivalent to 4 in Iran [1]. From the time of diagnosis, it usually takes less than two weeks for the patients to die, during which the companions may not be able to see the patient, so it is natural that family members of the deceased may not be able to adjust themselves to the grief [2].

Grief is a set of feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that people experience in the face of loss or the threat of loss. While mourning is natural and pervasive in all human societies, the expression of grief is different among individuals [3]. Grief is not considered a disorder and 6 months after the loss, the symptoms of mourning decrease [4]. About 10 percent of the bereaved also experience complex grief, which is called morbid or long-term grief [5]. This estimate is higher during crises [6]. Given the striking similarities between natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., high mortality, many secondary stressors, severe social deprivation), similar patterns in spiritual, mental, and social health symptoms are predicted among people affected by COVID-19 [7]. As spiritual and psychosocial health problems increase in natural disasters such as pandemics [8], less attention is given to the responses to intense grief and long and complicated mourning.

Complicated grief occurs when certain aspects of natural grief are distorted or exacerbated, such as failure to perform current cultural events, leading to psychosocial dysfunction [9]. The cause of death has always been recognized as a factor in the grief response, and there is evidence that sudden death leads to a more severe reaction in survivors [10].

The prevalence of complex and long-term grief depends on the circumstances of death, age range, and other factors. Experiencing long-term grief was reported in parents (between 30 and 50%). In another study of unexpected family deaths, survivors experience between 5 and 20 percent of long-term reactions and complex grief [11]. The prevalence of complex grief is higher in people with depression, adaptation problems, and psychiatric patients. In an Iranian sample with specific socio-economic characteristics, the prevalence of complex grief was estimated to be 3.73% [12]. In the case of the COVID_19 pandemic, it is not possible to hold a mourning ceremony to prevent the disease, and even the burial of the deceased is done with the least possible number of people [13]. In the current situation, all social support is taken away from the survivors and they find themselves alone. Self-isolation and lack of communication with the environment intensify and prolong the grieving process [13, 14]. Challenges in performing new social roles and responsibilities (such as finances, parenting, supervision) and losing one's identity can lead to prolonged grief and complex mourning [15]. The process of grief can be influenced by social systems, media coverage, and people's attitudes towards the type of death [7]. Perceived social support is one of the factors that help increase recovery in the grieving process, especially in complex grief. In this situation, the person feels loved and valued and belongs to a network of communication [16]. Given the lack of research on grief after the global outbreak of the virus, it can be argued that the Covid-19 virus may increase the complex mourning in the world [17]. Family and social consequences of grief include decreased social cohesion, increased tendency to isolation, and weakened interpersonal communication skills. People also become cold and unmotivated about healthy behaviors [18].

As mentioned before, in the current context, in addition to the psychological and societal pressures on the families and survivors of the Covid-19 deceased, the loss of a guardian, lack of income, and economic pressures could exacerbate their problems. Some families have lost more than one loved one and remaining family members were under quarantine, supporting programs are needed in addition to grief counseling. As long as communities face this problem, having an indigenous program and model for the social rehabilitation of the families of the deceased can alleviate the problems caused by Covid-19 deaths. Therefore, this study aimed to design and develop inter-organizational psychosocial support for the family and survivors of the deceased Covid-19 and to pay attention to the inter-organizational aspects of providing psychosocial support.

Participants and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted in 2021. At first, all accessible search engines and databases, especially those for systematic reviews and guidelines were searched. Then, several focus group discussions and rounds of Delphi were carried out with 35 experts, who were selected purposively in the first phase.

The literature review was performed on databases that serve as references of guidelines and protocols for social workers and psychologists, such as the International Social Welfare Federation (FASW) website, the National Association of Social Workers, United States Social Network (NASW) and the International Network of Guidelines (GIN). Also, the databases of PubMed, Scopus, ISI (Web of sciences), the database of the World Health Organization, and PsychINFO were studied to review the articles from 2000 to 2020. The following keywords were searched: Psycho-social support in COVID-19, Psycho-social support, Psycho-social support for the family of the deceased, Psycho-social support in grief.

Extracted data were collected through the Delphi Method with 25 social workers and clients working at hospitals in Iran as well as experts and scholars in the field of mental health, experts of Welfare Organizations, Red Crescent center, Imam Khomeini Relief Committee, and Tehran Municipality. Inclusion criteria for forming the Delphi group were: having at least a master's degree in social work and psychology (general and clinical), people with a degree in psychiatry, having at least two years of working experience in health care centers, and willingness to collaborate in this study.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Ministry of Health. In all stages of the study, all ethical issues regarding review and qualitative research have been observed. Due to time constraints and critical conditions, the Delphi technique was performed in three rounds. In the Delphi method, a questionnaire was prepared with the help of research team members, and questions were asked about psychosocial support to crisis survivors and the services of welfare organizations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were asked to return their written feedbacks in 48 hours. The results were then reviewed, summarized, and returned to Delphi members. The results of the second round were summarized and the resulting process was shared and discussed in a focus group discussion session (Chart 1).

The findings of the Delphi method and resource review were examined using a focus group discussion method. Ten experts participated in three virtual sessions and one face-to-face session. A panel of experts was used to evaluate the validity and reliability of the interventions. The panel consisted of 5 social experts with work experience and familiarity with support organizations. The interventions were first piloted for two weeks in five cities (Tehran, Borujerd, Esfahan, Mashhad, and Qom) and then for six months (April 15-September 20) in all provinces of Iran (Table 1).

Table 1) Psychosocial interventions for the survivors of the deceased Covid-19 (Total number of deceased=52670)

Out of the 18560 households of deceased members, 4540 people were evaluated. The majority of them (24.5%) referred to Red Crescent Society and about 18.3% received grief counseling the least common type of intervention was training (2.42%).

Chart 1) Delphi results

Findings

After reviewing the sources, Delphi, and group discussion, a process with 5 steps was designed, which are: Initial social worker assessment, mental assessment by mental health experts, complete a checklist and send it to the expert in charge of social work at the university, providing social and economic interventions by social workers in cooperation with support organizations and finally follow-up, termination, and documentation (according to figure 1). The process of psychosocial support begins with an initial assessment in the hospitals. Patient evaluation includes case studies, family contact, and information from the treatment team about the patient's condition. The social worker provided the context for family members to communicate with the patient through observing social distance or virtual communication. After the death of the patient, the unpleasant news was reported to the family by the principles. In order to communicate with the survivors of the deceased, a list of the deceased and their family contact numbers were prepared by social workers and were sent to the mental health experts. The target groups were the survivors and families of the deceased Covid-19 patients who could receive psychosocial support according to the outlined process. Inclusion criteria are: the family of the deceased Corona, need to receive financial support and consulting services, Willingness to receive services, and Collaborate with the hospital social worker.

In the second stage, a mental assessment was performed by a mental health expert, and within 7 to 14 days after the death, the survivors were contacted by phone, and, while expressing sympathy, the purpose of the call was explained. If the family did not need specialized interventions, the intervention ended after informing and providing the necessary guidance. Grief counseling was provided for the family members who expressed the need for counseling. It was done in four stages of flexible event evaluation and increasing understanding of loss, coping with grief and mourning, retrieval and evaluation of treatment. People are referred to a psychiatrist if they need medication and emergency interventions. Given the role of each of the participating organizations in the protocol and the tasks assigned to them in Delphi, a checklist was designed to examine how to provide services quantitatively and qualitatively. Checklists were completed daily and sent to the university's social work expert for evaluation and referral to support organizations. The third step was to evaluate the checklist and plan for referrals and follow-up. The checklist includes the type, quantity, and quality of services provided. The final step includes follow-up, conclusion, documenting, and reporting performance. To prevent the spread of disease, follow-ups were done only by phone calls. The purpose of the follow-up was to review the receipt of services and support to which the client has been referred for a reason. If the desired service and support were not received by the client, the follow-up continued until the desired result was achieved.

Figure 1) Inter-organizational psychosocial support for the families and survivors of COVID-19 deceased

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly affected all countries of the world, and medical centers, as pioneers of services, had little opportunity to adapt. The number of deaths is increasing every day and the survivors are facing many mental, psychological, and economic problems. In this study, inter-organizational interventions were designed to support survivors and families of the deceased since their hospital stay, and this support is provided inter-organizationally. The process of providing psychosocial support to the survivors and families of the Covid-19 deceased, like most specialized processes, begins with an initial assessment. Social work experts believed that assessment helps us gain a better understanding of the patient and his or her condition. Studies are suggested that assessment provides a framework that improves communication and collaboration between the client and the social worker [19, 20]. In this study, two basic service categories are provided to survivors (grief counseling (by mental health experts) and advocacy and referral (by social workers).

Grief counseling is important because it can increase our understanding of how to prevent negative consequences. There are two types of intervention associated with grief, counseling, and treatment. In this study, grief consultations are performed by mental health experts and if the person needs treatment, s/he is introduced to psychiatric clinics. The results of studies showed that counseling and treatment are effective for the survivors of the deceased [2, 5, 12, 21]. Unexpected loss is associated with more severe grief reactions, and survivors experience more severe grief and more severe mental and social health problems in the sudden death of a loved one (including earthquake and Covid-19) than in natural death or death from chronic illness [2, 12, 20]. Old age, the loss of a loved person, and low socioeconomic status are also major predictors of complex grief [12].

One of the most important services provided by social workers is social resource management and referral, which is done internally and externally. Bourguet concluded that counselors are usually less often referred to physicians and specialists, while a large proportion of counselors' referrals are to physicians [22]. He also concluded that the best referral is made formally, using a written letter [23]. If the referral is superficial and unprincipled, it can endanger the client or double his problem. Attention to the phenomenon of transmission and counter-transmission, referral to a committed and specialized person, observance of gender or cultural homogeneity are among the principles that are considered in referral. Social workers establish a link between clients and social resources through advocacy.

Dalrymple believes that advocacy is the heart of social work and increases the quality of life, justice, and social enjoyment [23]. Rivera and Wilks consider two types of internal and external advocacy [24-26]. In the present study, in addition to the internal advocacy provided by the social workers of the hospitals, the external advocacy is provided through referrals to relief and welfare institutions. Due to time constraints and emergencies, it was not possible to evaluate the effectiveness of the protocol. It is suggested that this be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

Mourning counseling, social and economic support for the families of the deceased A participatory model with an approach of internal and cross-sectoral cooperation was implemented in the country to prevent complex mourning. According to the evaluation reports of this research project, it can be used to strengthen cross-sectoral cooperation for other crises and problems, if needed in the future.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all the experts and participants in the research process.

Ethical Permissions: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Ministry of Health. (Letter number 100/193).

Conflicts of Interests: There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Authors’ Contributions: Sabzi Khoshnami M. (First Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (16%); Javadi S.M.H. (Second Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher (14%); Noruzi S. (Third Author), Introduction Writer/Methodologist/Main Researcher/Statistical Analyst/Discussion Writer (14%); Vahdani B. (Fourth Author) Introduction Writer (14%); Tahmasebi S. (Fifth Author) Introduction Writer (14%); Azari Arghun T. (Sixth Author), Discussion Writer (14%); Sayar S. (Seventh Author), Discussion Writer (14%).

Funding/Sources: There was no funding for this research.

Keywords:

References

1. WHO. Novel coronavirus-2019 , technical and guidance for health workers. Geneva: WHO; 2020. [Link]

2. Vahdani B, Javadi SMH, Sabzi Khoshnami M, Arian M. Grief Process and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Wise Intervention in Vulnerable Groups and Survivors. Iranian J Psychiatry Behavl Sci. 2020;14(2);e103855. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.103855]

3. Esmaeilpour K, Bakhshalizadeh Moradi S. The severity of grief reactions following death of first-grade relatives. Iranian J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2015;20(4):363-71. [Link]

4. Sanderson C, Lobb EA, Mowll J, Butow PN, McGowan N, Price MA. Signs of post-traumatic stress disorder in caregivers following an expected death: A qualitative study. Palliative Med. 2013;27(7):625-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0269216313483663] [PMID]

5. Shear MK, SimonN, Wall M, Zisook S, Neimeyer R, Duan N, et al. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM‐5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(2):103-17 [Link] [DOI:10.1002/da.20780] [PMID] [PMCID]

6. Mousavi SS, Zargar Y, Davodi I, Naami A. The effectiveness of complicated grief treatment on symptoms of complicated grief: a single case research. J Couns Res. 2016;15(58):135-55. [Persian] [Link]

7. Eisma MC, Boelen PA, Lenferink LI. Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:113031. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Javadi SMH, Nateghi N. Coronavirus and its psychological effects on elderly population. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1-2. [Link]

9. Yousefpour N, Akbari A, Ahangari E, Samari AA. An investigation of the effectiveness of psychotherapy based on the life quality improvement on the reduction of depression of those suffering from complicated grief. Res Clin Psychol Couns. 2017;7:21-37. [Persian] [Link]

10. Miyabayashi S, Yasuda J. Effects of loss from suicide, accidents, acute illness and chronic illness on bereaved spouses and parents in Japan: Their general health, depressive mood, and grief reaction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(5):502-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01699.x] [PMID]

11. Javadi SMH, Sajadian M. Coronavirus pandemic a factor in delayed mourning in survivors: A letter to the editor. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2020;23(1):2-7. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JAMS.23.1.4578.3]

12. Assare M, Firouz Kohi Moghadam M, Karimi M, Hosseini M. Complicated grief: a descriptive cross-sectional prevalence study from Iran. Shenakht J Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;1(2):40-6. [Persian] [Link]

13. Damia D. Inidividual and environmental corrleates of anxiety in parentally bereaved children [dissertation]. Michigan: University of Michigan; 2013. [Link]

14. Chamani Ghalandari R, Dokaneifard F, Rezaei R. The effectiveness of semantic therapy training on psychological resilience and psychological well-being of mourning women. Shenakht J Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;6(4):26-36. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/shenakht.6.4.26]

15. Diolaiuti F, Marazziti D, Beatino MF, Mucci F, Pozza A. Impact and consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on complicated grief and persistent complex bereavement disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113916. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113916] [PMID] [PMCID]

16. Baglama B, Atak IE. Posttraumatic growth and related factors among postoperative breast cancer patients. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2015;190:448-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.024]

17. Baker SR, Farrokhnia RA, Meyer S, Pagel M, Yannelis C. How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Asset Pricing Stud. 2020:raaa009. [Link] [DOI:10.3386/w26949]

18. Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006. 11(3):277-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/13548500600595053] [PMID]

19. Berger RM, Kelly JJ. Social work in the ecological crisis. Soc Work. 1993;38:521-6. [Link]

20. Schaub J, Willis P, Dunk-West P. Accounting for self, sex and sexuality in UK social Workers' knowledge base: findings from an exploratory study. Br J Socl Work. 2017;47(2):427-46. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/bjsw/bcw015]

21. Lewis G, Fox S. Between theory and therapy: Grief and loss skills-based training for hospital social workers. Adv Soc Work Welfare Educ. 2019;21(1):110. [Link]

22. Bourguet C, Gilchrist V, McCord G. The consultation and referral process: a report from NEON (Northeastern Ohio Network Research Group). J Fam Pract. 1998;46:47-53. [Link]

23. Dalrymple J, Boylan J. Effective advocacy in social work. New York: SAGE; 2013. [Link] [DOI:10.4135/9781473957718]

24. Harms L, Boddy J, Hickey L, Hay K, Alexander M, Briggs L, et al. Post-disaster social work research: A scoping review of the evidence for practice. Int Soc Work. 2020. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0020872820904135]

25. Wilks T. Advocacy and social work practice. London: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012. [Link]

26. Javadi SMH, Arian M, Qorbani-Vanajemi M. The need for psychosocial interventions to manage the coronavirus crisis. Iranian J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2020;14(1):e102546. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.102546]