Volume 13, Issue 1 (2021)

Iran J War Public Health 2021, 13(1): 41-47 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/03/16 | Accepted: 2021/05/14 | Published: 2021/09/11

Received: 2021/03/16 | Accepted: 2021/05/14 | Published: 2021/09/11

How to cite this article

Mousavi B, Asgari M, Soroush M, Montazeri A. Psychiatric Disorder and Quality of Life in Female Survivors of the Iran-Iraq war; Three Decades after Injuries. Iran J War Public Health 2021; 13 (1) :41-47

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-968-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-968-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Prevention Department, Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran , mousavi.b@gmail.com

2- Statistic Department, Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

3- Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

4- Mental Health Research Group, Health Metrics Research Center, Iranian Institute for Health Sciences Research, Tehran, Iran

2- Statistic Department, Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

3- Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

4- Mental Health Research Group, Health Metrics Research Center, Iranian Institute for Health Sciences Research, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (486 Views)

Introduction

More than fifty percent of the combat injuries are mostly extremities injuries and have a major impact on the disabled and the health care system [1]. Limited studies directly address combat-related stress and associated mental health consequences on the female [2]. There is a knowledge gap in the longer-term health effects of combat injuries on females [2, 3]; however, few studies related to chronic conditions [4]. Most of the studies have primarily focused on the male population, and gender differences in medical and mental health needs in the Iran-Iraq war have not yet been reported [5-8].

Understanding the impact of combat exposure and the physical and mental health needs of female war survivors are important to provide high-quality care. Females with physical disabilities due to combat-related injuries suffer more from mental health disorders [9]. Furthermore, females may experience stressors that vary from men, including poor social and family support [10]. Comparing to males, the female was more likely to have depression and adjustment disorders. They also remain more single with greater rates of health care service use [9].

Despite some surveys on the mental health of war casualties, there has never been a survey to assess all aspects of mental health among war-related injuries in females. More than 550,000 survivors of the Iran-Iraq war, both veterans and civilians [11] and 2% are female. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has been measured in various male veterans in different settings [5-8]. While female mental health readjustment issues might mirror the male population, they may face unique threats to their mental health. To our knowledge, no previous study has described the quality of life and mental health in females disabled with war-related etiologies.

Determination of the psychological status of female war victims can help detect mental disorders and plan for their quality of life improvement, and not enough research focused on the impact of war on the psychological and health-related quality of life of female war victims. Therefore, Therefore, we used the SCL-90-R questionnaire to determine nine domains of mental health, as well as, sf-36 for quality of life.

Instrument & Methods

In this Descriptive cross-sectional study, female survivors of the Iran-Iraq war participated in 2018. The baseline statistics of all injured veterans of the Iran–Iraq war were registered in the Veterans and Martyrs Affair Foundation (VMAF) that they are more than five thousand [7]. The 300 injured female survivors who suffered from severe disabilities were invited for psychological assessment and health-related quality of life.

Three questionnaire were used:

More than fifty percent of the combat injuries are mostly extremities injuries and have a major impact on the disabled and the health care system [1]. Limited studies directly address combat-related stress and associated mental health consequences on the female [2]. There is a knowledge gap in the longer-term health effects of combat injuries on females [2, 3]; however, few studies related to chronic conditions [4]. Most of the studies have primarily focused on the male population, and gender differences in medical and mental health needs in the Iran-Iraq war have not yet been reported [5-8].

Understanding the impact of combat exposure and the physical and mental health needs of female war survivors are important to provide high-quality care. Females with physical disabilities due to combat-related injuries suffer more from mental health disorders [9]. Furthermore, females may experience stressors that vary from men, including poor social and family support [10]. Comparing to males, the female was more likely to have depression and adjustment disorders. They also remain more single with greater rates of health care service use [9].

Despite some surveys on the mental health of war casualties, there has never been a survey to assess all aspects of mental health among war-related injuries in females. More than 550,000 survivors of the Iran-Iraq war, both veterans and civilians [11] and 2% are female. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has been measured in various male veterans in different settings [5-8]. While female mental health readjustment issues might mirror the male population, they may face unique threats to their mental health. To our knowledge, no previous study has described the quality of life and mental health in females disabled with war-related etiologies.

Determination of the psychological status of female war victims can help detect mental disorders and plan for their quality of life improvement, and not enough research focused on the impact of war on the psychological and health-related quality of life of female war victims. Therefore, Therefore, we used the SCL-90-R questionnaire to determine nine domains of mental health, as well as, sf-36 for quality of life.

Instrument & Methods

In this Descriptive cross-sectional study, female survivors of the Iran-Iraq war participated in 2018. The baseline statistics of all injured veterans of the Iran–Iraq war were registered in the Veterans and Martyrs Affair Foundation (VMAF) that they are more than five thousand [7]. The 300 injured female survivors who suffered from severe disabilities were invited for psychological assessment and health-related quality of life.

Three questionnaire were used:

- The Persian version of the health-related quality of life (HRQoL-SF36) questionnaire [12] was used. Its psychometric properties are well documented. SF-36 is a generic questionnaire consisting of 36 questions that measure eight health-related domains of quality of life. These domains include physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health. The first four domains comprise physical component summary (PCS), while the latter indicates mental component summary (MCS). Scores on each subscale range from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the worst and 100 representing the best health-related quality of life [12]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire had been validated in Montazeri et al. study [12]. The internal consistency showed that all eight SF-36 scales met the minimum reliability standard, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranging from 0.77 to 0.90 with the exception of the vitality scale (α=0.65). Convergent validity using each item correlation with its hypothesized scale showed satisfactory results (all correlations above 0.40 ranging from 0.58 to 0.95).

- The Symptom Check List 90 Revised (SCL-90-R), a 90-item psychiatric symptoms checklist that assesses psychiatric symptomatology and psychological reactions, was also used. The SCL-90-R is a self-report system inventory [13] designed to reflect the psychological symptom patterns of the community. The SCL-90-R was translated into Persian, which is simple and comprehensible to Iranian, and its validity and reliability were approved [14]. Internal consistency for all dimensions of the questionnaire was more than 0.70. The correlation coefficient of the questionnaire based on pre-test and post-test was 0.97. The SCL-90 sensitivity and specificity compared to DSM III-R were 0.94 and 0.98, respectively [14]. Each item in SCL-90-R is rated on a five-point scale of distress (0-4) ranging from "not at all" to "extremely". The nine psychopathology symptom dimensions are labeled as: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobia, paranoid ideation, and psychosis, and a Global Severity Index (GSI) derived from this questionnaire. The score in each domain reflects the presence of mental problems, as well as their severity. The test time is about 10-15 minutes. Respondents rated 90 items using a 5-point scale to measure the extent to which they have experienced the listed symptoms during the last seven days. Raw scores are calculated by dividing the sum of scores for a dimension by the number of items. The SCL-90-R also has three global indexes: the GSI measures the extent or depth of the individual's psychiatric disturbances; the Positive Symptom Total (PST) counts the total number of questions rated above 1 point; the Positive Symptoms Distress Index (PSDI) is calculated by dividing the sum of all items values by the PST. Since GSI is suggested to be the best single indicator of the current level of the disorder, in this study, we only reported GSI and raw scores of 9 SCL-90-R subscales [13]. An optimal cut-off point of 0.4 was considered based on the standardized test results for Iran [14, 15].

- Demographic characteristics of the surviving injured females were collected from VMFA data bank. The study was approved by the Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran. Before the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were asked to fill 3 questionnaires. The interviews were conducted separately for each participant, face-to-face, for about 30-40 minutes for each participant. The scores data obtained from female war survivors have been compared with the normal Iranian female population scores achieved of both Iranian SCL-90 cut of point and the samples of the Montazeri et al. study [12, 13].

Descriptive statistics were used. Chi-square test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and one-sample t-test were applied to assess the differences between groups where appropriate. The logistic regression model was used to quantify the contribution of independent variables to the female war survivors' PCS and MCS of the SF-36. Independent variables included female war survivors' characteristics: Age, education, employment, psychiatric disorders, the severity of casualties, and comorbidity. Relative to the mean PCS and MCS scores, the study sample was divided into two groups, those who scored equal or greater than mean and those who scored lower than mean. We consider the lower scores of the mean as the baseline. As a rough guide, the mean score for any given population seems to be the best cut-off point to determine whether a group or individual scores above or below the average. All statistical analyzes of the data were performed using the R 3.4.3 Software for Windows.

Findings

The mean age of participants was 44.47±14.06 years. The majority of the population were unemployed (81.9%: N=113), and less than half of the survivors never married (40.6%: N=56). A lower diploma was observed in the most (60.9%: N=84), then diploma 12.3% (N=17) and higher education 26.8% (N=37). Severe disabilities were observed in 44.9% (N=62) of the cases. The injuries included spinal cord injuries (21 cases), blindness (7 cases), bilateral lower limb amputation (40 cases), bilateral upper limb amputation (2 cases), unilateral blindness (38 cases), unilateral upper/lower limb amputation (32 cases), and severe lung-eye injuries due to sulfur mustard exposure (6 cases). In 67 of the female survivors (46.8%), injuries happened after the war (1988- 2016) due to landmine and explosive remnants of war.

Quality of life scores (all eight subscales) in female war survivors was significantly lower than the general female Iranian population (p<0.001;

Figure 1).

Figure 1) Quality of life scores in female war survivors and a general Iranian female population**

(*:Pvalue<0.001; PF: Physical functioning, RF: Role physical, BP: Bodily pain, GH: General Health, V: Vitality, SF: Social functioning, RE: Role emotional, and MH: Mental health. **:Derived from Montazeri et al. study [12]

Females who suffered from chemical warfare injuries or being injured with explosive remnants of war at younger ages had significantly lower mean scores in all 8 subscales of HRQOL-SF36 and both PCS and MCS compared to their counterparts (p<0.01). The SCL-90 psychological subscales mean scores lower than 2 were as somatization: 66.5% (n=71); obsessive-compulsive: 64.6% (n=69); interpersonal sensitivity: 64.3% (n=68); depression: 66.0% (n=70); anxiety: 64.2% (n=68); hostility: 50.0% (n=53); phobia: 50.9% (n=54); paranoid ideation: 68.4% (n=62) and psychosis: 49.1% (n=52). Somatization, hostility, and paranoid perceptions had a significant effect on the PCS (Table 1).

Somatization had the greatest impact; for each unit increase in the score of this variable, the score of the PCS decreases by 15 units. Depression and hostility had a significant effect on MCS. Depression had more impact on the decrease in the MCS. For each unit increase in the score of depression, the score of the MCS decreases by ten units. The results obtained from logistic regression analysis indicated that GSI score was the only determinant for both poor PCS (OR=0.18, 95%CI=0.87 to 0.37, p<0.001) and MCS (OR=0.13, 95%CI=0.06 to 0.30, p<0.001; Table 2).

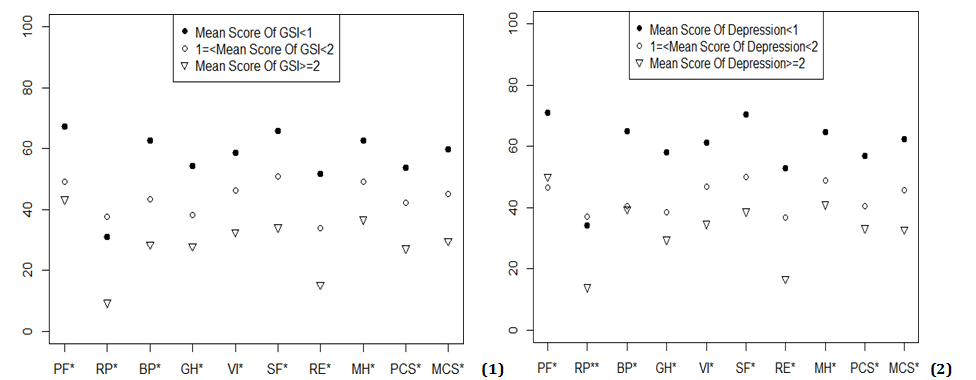

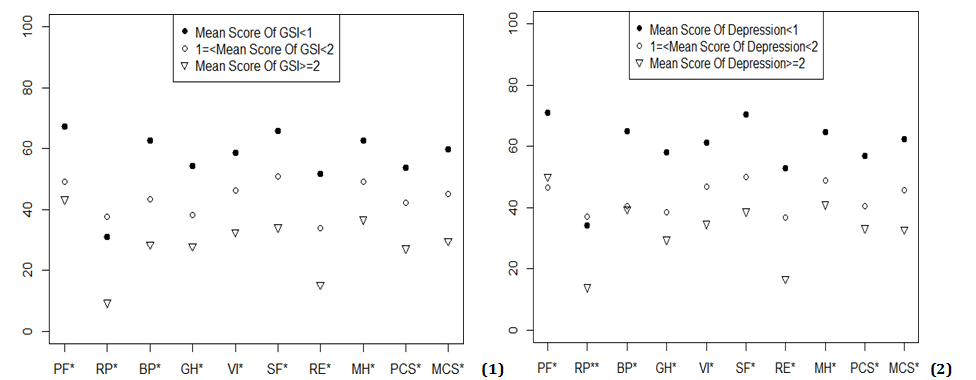

Quality of life in female war survivors based on GSI, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety mean scores were demonstrated in Figure 2 (p<0.05). These figures showed that as the mean scores of GSI, depression, and anxiety rising, the quality-of-life scores in 8 domains of SF-36 were dropped. Role physical, role emotional, and general health had the least scores (below 20) in females' war survivors when their scores of SCL-90 in four subscales including GSI, depression, anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity were equal or more than 2 (p<0.05).

Findings

The mean age of participants was 44.47±14.06 years. The majority of the population were unemployed (81.9%: N=113), and less than half of the survivors never married (40.6%: N=56). A lower diploma was observed in the most (60.9%: N=84), then diploma 12.3% (N=17) and higher education 26.8% (N=37). Severe disabilities were observed in 44.9% (N=62) of the cases. The injuries included spinal cord injuries (21 cases), blindness (7 cases), bilateral lower limb amputation (40 cases), bilateral upper limb amputation (2 cases), unilateral blindness (38 cases), unilateral upper/lower limb amputation (32 cases), and severe lung-eye injuries due to sulfur mustard exposure (6 cases). In 67 of the female survivors (46.8%), injuries happened after the war (1988- 2016) due to landmine and explosive remnants of war.

Quality of life scores (all eight subscales) in female war survivors was significantly lower than the general female Iranian population (p<0.001;

Figure 1).

Figure 1) Quality of life scores in female war survivors and a general Iranian female population**

(*:Pvalue<0.001; PF: Physical functioning, RF: Role physical, BP: Bodily pain, GH: General Health, V: Vitality, SF: Social functioning, RE: Role emotional, and MH: Mental health. **:Derived from Montazeri et al. study [12]

Females who suffered from chemical warfare injuries or being injured with explosive remnants of war at younger ages had significantly lower mean scores in all 8 subscales of HRQOL-SF36 and both PCS and MCS compared to their counterparts (p<0.01). The SCL-90 psychological subscales mean scores lower than 2 were as somatization: 66.5% (n=71); obsessive-compulsive: 64.6% (n=69); interpersonal sensitivity: 64.3% (n=68); depression: 66.0% (n=70); anxiety: 64.2% (n=68); hostility: 50.0% (n=53); phobia: 50.9% (n=54); paranoid ideation: 68.4% (n=62) and psychosis: 49.1% (n=52). Somatization, hostility, and paranoid perceptions had a significant effect on the PCS (Table 1).

Somatization had the greatest impact; for each unit increase in the score of this variable, the score of the PCS decreases by 15 units. Depression and hostility had a significant effect on MCS. Depression had more impact on the decrease in the MCS. For each unit increase in the score of depression, the score of the MCS decreases by ten units. The results obtained from logistic regression analysis indicated that GSI score was the only determinant for both poor PCS (OR=0.18, 95%CI=0.87 to 0.37, p<0.001) and MCS (OR=0.13, 95%CI=0.06 to 0.30, p<0.001; Table 2).

Quality of life in female war survivors based on GSI, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety mean scores were demonstrated in Figure 2 (p<0.05). These figures showed that as the mean scores of GSI, depression, and anxiety rising, the quality-of-life scores in 8 domains of SF-36 were dropped. Role physical, role emotional, and general health had the least scores (below 20) in females' war survivors when their scores of SCL-90 in four subscales including GSI, depression, anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity were equal or more than 2 (p<0.05).

Table 1) Association of 9 dimensions of SCL-90 with SF-36 physical and mental component scales (n=138)

Table 2) Determinants of poor physical and mental components of quality of life in the female with war-related injuries (N=138)

Figure 2) Quality of life in female war survivors based on1- GSI, 2- Depression, 3- Anxiety, 4- Interpersonal sensitivity mean scores. PF: Physical functioning, RF: Role physical, BP: Bodily pain, GH: General Health, V: Vitality, SF: Social functioning, RE: Role emotional, and MH: Mental health. *:p<0.05

Table 2) Determinants of poor physical and mental components of quality of life in the female with war-related injuries (N=138)

Figure 2) Quality of life in female war survivors based on1- GSI, 2- Depression, 3- Anxiety, 4- Interpersonal sensitivity mean scores. PF: Physical functioning, RF: Role physical, BP: Bodily pain, GH: General Health, V: Vitality, SF: Social functioning, RE: Role emotional, and MH: Mental health. *:p<0.05

Continue of Figure 2) Quality of life in female war survivors based on1- GSI, 2- Depression, 3- Anxiety, 4- Interpersonal sensitivity mean scores. PF: Physical functioning, RF: Role physical, BP: Bodily pain, GH: General Health, V: Vitality, SF: Social functioning, RE: Role emotional, and MH: Mental health. *:p<0.05

Discussion

Several key outcomes were revealed in this study. First, relative to normal population norms, the female survivors reported more psychiatric symptomatology on the SCL–90–R. This increase was noticeable mainly for depression, somatization, obsessive-compulsive and interpersonal sensitivity. Second, the females suffered from poor physical and mental quality of life. Third, somatization, anger/hostility and paranoid ideation were similarly correlated with the participants' poor quality of life with more association to the Anger/hostility. Our results point to the significant impact of war-related distress in determining participants' QOL and psychiatric symptomatology rates.

The impact of long-term mental health and cumulative psychosocial adversity has not been adequately investigated, but the prevalence and severity of war-related violence in exposed women increase psychiatric disorders. Systematic review research has been done on the prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the Iranian population following disasters and wars, and 47 studies were included in this meta-analysis. This study showed that the war injured male veterans and their female spouses had been the subjects of some studies, but none of these researches were assessed the mental health of female war survivors. PTSD related to war, and the pooled prevalence was 47% [5].

The Iran-Iraq war accounts for 30-46% of the psychological disorders, especially PTSD, on Iranian veterans [16-20]. During the eight-year war, exposure to irregular air attacks and massive artillery fire caused more devastating consequences [5]. Other countries involving in war reported an increased rate of mental disorders, which is in line with our results, and the rate of mental disorders and PTSD is 2-5 times higher [21, 22]. Some of these differences might be due to the gap between exposure to war violence and time of the survey, experiencing varieties of war events, and the severity of such exposures. Subordinate social status and continuous responsibility for the care of others put the female survivors at higher risk, as well. Additional risk factors such as negative life experiences/events and stressors besides the war injuries are significantly interrelated with more depression, anxiety and somatic symptoms.

Anxiety and other mental disorders were detected among half of war-injured with worse marital relations and a higher rate in war-wounded children [23, 24]. In our study, female war survivors with lower GIS are likely to experience poorer physical functioning and lower objective and subjective living conditions. Younger age, chemical warfare injuries, and GIS were predictive factors for the poor quality of life. More than half of the participants were single, less educated (lower diploma) and unemployed; improving physical function recovers the individual's ability to stay employed. Female survivors need support from the employer, health authorities, and the educational system to optimize their adaption and back to life and community reintegration. Psychological disorders are important outcomes having a noticeable impact on quality of life and overall well-being. The literature and evidence on mental disorders and quality of life in female war survivors are restricted [25]. Female mental health issues are expected to mirror the male veteran population, but women may also experience unique threats. Despite provided mental health facilities for veterans transitioning to normal life, the problems continue or even worsen, especially in hostility/anger outbursts, tension in family relationships, depression, and substance use [26]. Development and design of an intervention to improve the gender awareness of healthcare providers showed successfully increased gender-specific sensitivity and knowledge [27].

Mental health problem rates differ in gender populations, with the female having higher adjustment disorders and depression rates and men having a higher rate of PTSD [28]. Some studies found small or non-significant differences [27, 29, 30], while the opposite, some found that the female gender was linked with more PTSD [31, 32]. Additionally, females had greater rates of health care service use, highlighting the complexity of female health care. These findings raise approaches concerning outreach to females in the same situations but do not use mental health care [9]. Consequently, health care providers need to support improved inclusive women's health services [33]. Further research could help to fully identify the role of gender in increase mental disorders on the Iranian side.

The majority of females' physical and mental health issues are not captured by research conducted in Iran. This raising key concerns of worthy further research need to address; coping with disabilities, readjustment, gender assault/harassment and interpersonal stressors. The impact of war casualties is mostly predicated on the experiences of males, studies on women's health expanding an opportunity to capture the experiences of female war survivors more effectively. Our study revealed several essentials, including better-quality access to care, mental health counseling/management and implications for policymakers.

Our findings indicate that being exposed to direct and indirect combat-related stressors is experienced by numerous females. Some repeatedly were subject to combat-related exposure and injuries. Due to this exposure and stress, females might experience sleep difficulties, interpersonal conflicts, and adjustment issues in family with their spouses and children [34]. These need to be addressed in future studies.

This study was conducted to explore the mental health and quality of life among female war survivors. The present study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the data presented are based on small sample size and cannot be generalized to all female war survivors because we only had access to data from VMAF who had severe disabilities. Second, findings relied on the use of SCL-90 and HRQOL-SF36 measures designed to screen for physical and mental health, which cannot be used instead of formal diagnostic procedures. Third, because data regarding females' mental health before injuries were not available, the effects of war-related stressors on the participant's health outcome could not be directed. Stressors identified in other studies included child care, financial situation, employment as stressors related to female war survivors before, during, and post injuries have not been identified [34]. This area needs further investigation whether the female survivors

indicated seeking physical or mental health assistance or reported any difficulties in community reintegration and back to normal life.

Conclusion

The female injured survivors have more psychiatric symptomatology than the normal population, and the majority are suspected cases of mental disorder and poor health-related quality of life. Depression, somatization, obsessive-compulsive and interpersonal sensitivity are the most common psychiatric symptomatology. Chemical warfare injuries have a more negative impact on health-related quality of life compared to other war-related disabilities. The Global Severity Index score is the most important determinant for both poor PCS.

Acknowledgments: -

Ethical Permissions: The research ethics committee of the Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), approved the study (88-E-P-107).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions: Mousavi B. (First Author), Introduction Writer (25%); Asgari M. (Second Author), Methodologist (25%); Soroush M. (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Montazeri A. (Forth Author), Discussion Writer (25%).

Funding/Support: Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), and Veterans and Martyrs Affair Foundation (VMAF) funded the study.

Several key outcomes were revealed in this study. First, relative to normal population norms, the female survivors reported more psychiatric symptomatology on the SCL–90–R. This increase was noticeable mainly for depression, somatization, obsessive-compulsive and interpersonal sensitivity. Second, the females suffered from poor physical and mental quality of life. Third, somatization, anger/hostility and paranoid ideation were similarly correlated with the participants' poor quality of life with more association to the Anger/hostility. Our results point to the significant impact of war-related distress in determining participants' QOL and psychiatric symptomatology rates.

The impact of long-term mental health and cumulative psychosocial adversity has not been adequately investigated, but the prevalence and severity of war-related violence in exposed women increase psychiatric disorders. Systematic review research has been done on the prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the Iranian population following disasters and wars, and 47 studies were included in this meta-analysis. This study showed that the war injured male veterans and their female spouses had been the subjects of some studies, but none of these researches were assessed the mental health of female war survivors. PTSD related to war, and the pooled prevalence was 47% [5].

The Iran-Iraq war accounts for 30-46% of the psychological disorders, especially PTSD, on Iranian veterans [16-20]. During the eight-year war, exposure to irregular air attacks and massive artillery fire caused more devastating consequences [5]. Other countries involving in war reported an increased rate of mental disorders, which is in line with our results, and the rate of mental disorders and PTSD is 2-5 times higher [21, 22]. Some of these differences might be due to the gap between exposure to war violence and time of the survey, experiencing varieties of war events, and the severity of such exposures. Subordinate social status and continuous responsibility for the care of others put the female survivors at higher risk, as well. Additional risk factors such as negative life experiences/events and stressors besides the war injuries are significantly interrelated with more depression, anxiety and somatic symptoms.

Anxiety and other mental disorders were detected among half of war-injured with worse marital relations and a higher rate in war-wounded children [23, 24]. In our study, female war survivors with lower GIS are likely to experience poorer physical functioning and lower objective and subjective living conditions. Younger age, chemical warfare injuries, and GIS were predictive factors for the poor quality of life. More than half of the participants were single, less educated (lower diploma) and unemployed; improving physical function recovers the individual's ability to stay employed. Female survivors need support from the employer, health authorities, and the educational system to optimize their adaption and back to life and community reintegration. Psychological disorders are important outcomes having a noticeable impact on quality of life and overall well-being. The literature and evidence on mental disorders and quality of life in female war survivors are restricted [25]. Female mental health issues are expected to mirror the male veteran population, but women may also experience unique threats. Despite provided mental health facilities for veterans transitioning to normal life, the problems continue or even worsen, especially in hostility/anger outbursts, tension in family relationships, depression, and substance use [26]. Development and design of an intervention to improve the gender awareness of healthcare providers showed successfully increased gender-specific sensitivity and knowledge [27].

Mental health problem rates differ in gender populations, with the female having higher adjustment disorders and depression rates and men having a higher rate of PTSD [28]. Some studies found small or non-significant differences [27, 29, 30], while the opposite, some found that the female gender was linked with more PTSD [31, 32]. Additionally, females had greater rates of health care service use, highlighting the complexity of female health care. These findings raise approaches concerning outreach to females in the same situations but do not use mental health care [9]. Consequently, health care providers need to support improved inclusive women's health services [33]. Further research could help to fully identify the role of gender in increase mental disorders on the Iranian side.

The majority of females' physical and mental health issues are not captured by research conducted in Iran. This raising key concerns of worthy further research need to address; coping with disabilities, readjustment, gender assault/harassment and interpersonal stressors. The impact of war casualties is mostly predicated on the experiences of males, studies on women's health expanding an opportunity to capture the experiences of female war survivors more effectively. Our study revealed several essentials, including better-quality access to care, mental health counseling/management and implications for policymakers.

Our findings indicate that being exposed to direct and indirect combat-related stressors is experienced by numerous females. Some repeatedly were subject to combat-related exposure and injuries. Due to this exposure and stress, females might experience sleep difficulties, interpersonal conflicts, and adjustment issues in family with their spouses and children [34]. These need to be addressed in future studies.

This study was conducted to explore the mental health and quality of life among female war survivors. The present study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the data presented are based on small sample size and cannot be generalized to all female war survivors because we only had access to data from VMAF who had severe disabilities. Second, findings relied on the use of SCL-90 and HRQOL-SF36 measures designed to screen for physical and mental health, which cannot be used instead of formal diagnostic procedures. Third, because data regarding females' mental health before injuries were not available, the effects of war-related stressors on the participant's health outcome could not be directed. Stressors identified in other studies included child care, financial situation, employment as stressors related to female war survivors before, during, and post injuries have not been identified [34]. This area needs further investigation whether the female survivors

indicated seeking physical or mental health assistance or reported any difficulties in community reintegration and back to normal life.

Conclusion

The female injured survivors have more psychiatric symptomatology than the normal population, and the majority are suspected cases of mental disorder and poor health-related quality of life. Depression, somatization, obsessive-compulsive and interpersonal sensitivity are the most common psychiatric symptomatology. Chemical warfare injuries have a more negative impact on health-related quality of life compared to other war-related disabilities. The Global Severity Index score is the most important determinant for both poor PCS.

Acknowledgments: -

Ethical Permissions: The research ethics committee of the Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), approved the study (88-E-P-107).

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions: Mousavi B. (First Author), Introduction Writer (25%); Asgari M. (Second Author), Methodologist (25%); Soroush M. (Third Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Montazeri A. (Forth Author), Discussion Writer (25%).

Funding/Support: Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), and Veterans and Martyrs Affair Foundation (VMAF) funded the study.

Keywords:

References

1. Cross JD, Ficke JR, Hsu JR, Masini BD, Wenke JC. Battlefield orthopaedic injuries cause the majority of long-term disabilities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19 Suppl 1:1-7. [Link] [DOI:10.5435/00124635-201102001-00002]

2. Vogt D, Vaughn R, Glickman ME, Schultz M, Drainoni ML, Elwy R, et al. Gender differences in combat-related stressors and their association with postdeployment mental health in a nationally representative sample of US OEF/OIF veterans. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120(4):797-806. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0023452]

3. Runnals JJ, Garovoy N, McCutcheon SJ, Robbins AT, Mann-Wrobel MC, Elliott A, et al. Systematic of review of women veterans' mental health. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(5):485-502. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.012]

4. Dunan ER, Krebs EE, Ensrud K, Koeller E, MacDonald R, Velasquez T, et al. An evidence map of the women veterans' health research literature (2008-2015). J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1359-76. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11606-017-4152-5]

5. Sepahvand H, Mokhtari Hashtjini M, Salesi M, Sahraei H, Pirzad Jahromi G. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Iranian population following disasters and wars: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2019;13(1):66124. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs.66124]

6. Ganjparvar Z, Mousavi B, Masumi M, Soroush M, Montazeri A. Determinants of quality of life in the caregivers of Iranian war survivors with bilateral lower-limb amputation after more than two decades. Iran J Med Sci. 2016;41(4):257-64. [Persian] [Link]

7. Mousavi B, Soroush MR, Montazeri A. Quality of life in chemical warfare survivors with ophthalmologic injuries: The first results from Iran chemical warfare victims health assessment study. Health Qual life Outcomes. 2009;7:2. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-7-2]

8. Mousavi B, Seyed Hoseini Davarani SH, Soroush M, Jamali A, Khateri S, Talebi M, et al. Quality of life in caregivers of severely disabled war survivors. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40(3):139-47. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/rnj.159]

9. Haskell SG, Mattocks K, Goulet JL, Krebs EE, Skanderson M, Leslie D, et al. The burden of illness in the first year home: Do male and female VA users differ in health conditions and healthcare utilization. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(1):92-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.001]

10. Street AE, Vogt D, Dutra L. A new generation of women veterans: Stressors faced by women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):685-94. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.007]

11. Taebi G, Soroush MR, Modirian E, Khateri S, Mousavi B, Ganjparvar Z, et al. Human costs of Iraq's chemical war against Iran: An epidemiological study. Iran J War Public Health. 2015;7(2):115-21. [Persian] [Link]

12. Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:875-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5]

13. Rush AJ, First MB, Blacker D. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington: American Psychiatric Publication; 2009. pp. 81-4 [Link]

14. Bagheriyazdi A, Bolhari J, Shahmohammadi D. Psychiatric disorders in the rural district of Meybod (Yazd, Iran). Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 1994;1(1):32-41. [Persian] [Link]

15. Mirzaee R. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of SCL-90 test in Iran [dissertation]. Iran: Faculty of Literature and Humanities Sciences, Tehran University; 1980. [Persian] [Link]

16. Shafiee-Kamalabadi M, Bigdeli I, Alavi K, Kianersi F. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid personality disorders in the groups veterans Tehran city. J Clan Psycol. 2014;6(21):65-75. [Persian] [Link]

17. Nateghian S. Forgiveness and marital satisfaction in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and their wives. J Fundam Ment Health. 2008;10(37):33-46. [Persian] [Link]

18. Mohaghegh-Motlagh SJ, Momtazi S, Mousavinasab SN, Arab A, Saburi E, Saburi A. Post-traumatic stress disorder in male chemical injured war veterans compared to non-chemical war veterans. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2014;56(6):361-8. [Persian] [Link]

19. Poorafshar SA, Ahmadi K, Alyasi MH. Evaluation of secondary PTSD and marital satisfaction among spouses of PTSD veterans. J Mil Psychol. 2009;1(1):67-76. [Persian] [Link]

20. Hashemian F, Khoshnood K, Desai MM, Falahati F, Kasl S, Southwick S. Anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress in Iranian survivors of chemical warfare. JAMA. 2006;296(5):560-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jama.296.5.560]

21. Shaar KH. Post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents in Lebanon as wars gained in ferocity: A systematic review. J Public Health Res. 2013;2(2):17. [Link] [DOI:10.4081/jphr.2013.e17]

22. Richardson LK, Frueh BC, Acierno R. Prevalence estimates of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Critical review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(1):4-19. [Link] [DOI:10.3109/00048670903393597]

23. Ahmadi K, Reshadatjoo M, Karami GR, Anisi J. Evaluation of secondary post-traumatic stress disorder in chemical warfare victims' children. J Mil Med. 2010;12(3):153-9. [Persian] [Link]

24. Saki K, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Bahmani M. The study of intensity and frequency of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulting from war in Ilam city. Life Sci J. 2013;10:407-17. [Persian] [Link]

25. Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, Marx BP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: Extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8): 727-35. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006]

26. Derefinko KJ, Hallsell TA, Isaacs MB, Colvin LW, Salgado Garcia FIS, Bursac Z. Perceived needs of veterans transitioning from the military to civilian life. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2019;46(3):384-98. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11414-018-9633-8]

27. Kehle-Forbes SM, Harwood EM, Spoont MR, Sayer NA, Gerould H, Murdoch M. Experiences with VHA care: A qualitative study of U.S. women veterans with self-reported trauma histories. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):38. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12905-017-0395-x]

28. Seal KH, Metzier TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using department of veterans affairs healthcare, 2002-2008. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1651-8. [Link] [DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2008.150284]

29. Rona RJ, Fear NT, Hull L, Wessely S. Women in novel occupational roles: Mental health trends in the UK armed forces. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(2):329-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ije/dyl273]

30. Lapierre CB, Schwegler AF, LaBauve BJ. Posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms in soldiers returning from combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):933-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jts.20278]

31. Smith TC, Wingard DL, Ryan MAK, Kritz-Silverstein D, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, et al. Prior assault and posttraumatic stress disorder after combat deployment. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):505-12. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a9dff]

32. Tanielian TL, Jaycox L. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries and their consequences and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2008. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/e527612010-001]

33. Maynard C, Nelson K, Fihn SD. Characteristics of younger women veterans with service connected disabilities. Heliyon. 2019;1;5(3):01284 [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01284]

34. Krajewski-Jaime ER, Whitehead M, Kellman-Fritz J. Challenges and needs faced by female combat veterans. Int J Health Wellness Soc. 2013;3(2):73-83. [Link] [DOI:10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v03i02/41067]

Send email to the article author