Volume 14, Issue 2 (2022)

Iran J War Public Health 2022, 14(2): 147-155 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2022/01/20 | Accepted: 2022/04/13 | Published: 2022/05/30

Received: 2022/01/20 | Accepted: 2022/04/13 | Published: 2022/05/30

How to cite this article

Eyni S, Hashemi Z, Ebadi M. Relationship between Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies and Experiential Avoidance with Death Anxiety of Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: The mediating role of Coping Self-Efficac. Iran J War Public Health 2022; 14 (2) :147-155

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1107-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1107-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Psychology, University of Kurdistan, Sanandaj, Iran

2- Department of Psychology, University of Maragheh, Maragheh, Iran

3- Department of Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran

2- Department of Psychology, University of Maragheh, Maragheh, Iran

3- Department of Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (457 Views)

Introduction

One such challenge transitioning veterans may encounter is unmet mental health needs, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a trauma-related disorder in which the specific diagnostic criterion begins with the exposure to a traumatic and/or stressful event [1]. Evidence suggests that veterans are especially at risk of developing PTSD due to the potential stressors associated with combat exposure and military-related trauma. The prevalence of PTSD among veterans ranges from 11 to 30% based on the area of service [2]. Individuals with PTSD are also 80% more likely to develop symptoms that are consistent with another mental disorder when compared with individuals without PTSD symptoms [1]. Commonly, individuals with PTSD also suffer from depression, anxiety, and cognitive difficulties like poor concentration [3]. This means that when military individuals are exposed to combat, the risk of PTSD greatly increases and when PTSD develops, the individual has a significant risk of developing depression or anxiety in relation to the traumatic stress experienced.

The aftermath of war is fraught with a high density of post-war stressors that survivors face on a daily basis [4]. Death anxiety becomes a larger concern for the individual when exposed to a traumatic event where he/she is placed in a situation where there is a real threat of harm or death. Death anxiety is a conscious or unconscious psychological state resulting from a defense mechanism that can be triggered when people feel threatened by death [5]. The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association defines death anxiety as a feeling of unsafety, anxiety, or fear related to death or near-death [6]. Death anxiety will become more conscious and can become excessive in the face of death or death experiences. For soldiers, the most common form of this is exposure to war. Soldiers are exposed to the actual harm and fear of death, and the fear becomes heightened because it is no longer just the anticipation of a life-threatening situation or event, this leads to a change in death anxiety overall [7]. Research has shown that Iranian War veterans who have been exposed to death trauma on the battlefield may carry the added burden of unique cognitions and fears related to personal death [8]. Exposure to death and trauma on the battlefield is commonly recognized as a precursor to a posttraumatic stress disorder, but many veterans demonstrate resilience and are able to adjust positively to reentry into civilian life [9].

Cognitive emotion regulation strategies can be considered as one of the variables involved in the death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. This type of emotion regulation is concerned with how individuals manage the intake of information that is emotionally arousing through the use of cognition [10]. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies include processes such as cognitive restructuring, self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, other-blame, acceptance, planning, positive reappraisal, positive-refocusing and putting into perspective [11]. Maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have been proposed to contribute to the maintenance of PTSD [12]. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies except positive refocusing and reappraisal had significant independent main effects on symptoms of depression while only war experiences, self-blame and blaming others had significant main effects on conduct problems in war-affected youth [4]. Higher levels of emotion dysregulation were directed related to higher posttraumatic stress symptom (PTS) severity and lower quality of life (QOL), through more severe negative post-combat worldview and lower coping self-efficacy appraisals [13]. The research of [14] showed that catastrophizing and rumination were associated with more post-traumatic stress symptoms and higher psychological distress. On the other hand, positive reappraisal, refocus on planning, and acceptance was associated with fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms and lower psychological distress.

Another process that warrants examination in connection with the death anxiety of veterans with PTSD is experiential avoidance, defined as rigid behavioral attempts to alter the form, frequency, or intensity of unwanted private events (i.e., thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations) when such behavior impedes valued living [15]. The function of experiential avoidance is to control or minimize the impact of annoying experiences and can provide immediate and short-term relief that negatively reinforces behavior [16]. People who experience more experiential avoidance use more self-destruction, denial, emotional support, behavioral disruption, and self-blame, and experience more intense emotional experiences than pleasant and unpleasant stimuli [17]. A link between experiential avoidance and PTSD symptoms is well established, particularly cross-sectionally [18]. There is a link between negative affectivity, empirical avoidance, cognitive concerns, emotional non-acceptance, and symptoms of PTSD among traumatized individuals [19]. The results of [20] showed that a number of individual difference factors, including emotional distress intolerance, experiential avoidance and anxiety sensitivity, have been implicated in the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptomatology. Experimental avoidance for soldiers with high anxiety sensitivity and anxiety traits is used as an effective short-term strategy and causes PTSD in them [21].

The role of coping self-efficacy with regard to death anxiety appears to tap into a range of skills, beliefs and attitudes about self and death [22]. Self-efficacy is an important proactive “agentic” factor in posttraumatic recovery as well as other psychiatric disorders [23]. Agentic refers to intentionally being an agent of change through one’s actions. One domain-specific measure of self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy (CSE), concerns individuals’ “perceived self-efficacy for coping with challenges or threats” [24]. Self-efficacy plays a proactive role in adaptation to extremely stressful events and thus influences the development of PTSD [25]. Self‐efficacy moderates the relationship between combat exposure and PTSD severity [26]. The research studied the impact of coping skills on death anxiety and PTSD and found that self-efficacy was significantly related to psychiatric comorbidity and death anxiety [22]. On the other hand, a review of death anxiety literature shows self-efficacy is both a predictor and mediator of death anxiety [27].

A review of the research background shows that death anxiety is associated with PTSD and psychiatric comorbidity and coping strategies can impact on these health outcomes, what is not clear is the interrelationship between death anxiety, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, experiential avoidance and coping self-efficacy in veterans with PTSD. It is not clear whether coping self-efficacy would mediate the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance and death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. The impact of death anxiety is an overlooked, yet potentially important component for finding a treatment that focuses on core difficulties and not just the current manifestation of symptoms. On the other hand, war veterans are one of the assets of any society and their psychological problems cannot be ignored. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the causal modeling of death anxiety in veterans with PTSD based on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance with the mediating role of coping self-efficacy. Figure.1 shows the hypothetical model of death anxiety in veterans with PTSD.

One such challenge transitioning veterans may encounter is unmet mental health needs, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a trauma-related disorder in which the specific diagnostic criterion begins with the exposure to a traumatic and/or stressful event [1]. Evidence suggests that veterans are especially at risk of developing PTSD due to the potential stressors associated with combat exposure and military-related trauma. The prevalence of PTSD among veterans ranges from 11 to 30% based on the area of service [2]. Individuals with PTSD are also 80% more likely to develop symptoms that are consistent with another mental disorder when compared with individuals without PTSD symptoms [1]. Commonly, individuals with PTSD also suffer from depression, anxiety, and cognitive difficulties like poor concentration [3]. This means that when military individuals are exposed to combat, the risk of PTSD greatly increases and when PTSD develops, the individual has a significant risk of developing depression or anxiety in relation to the traumatic stress experienced.

The aftermath of war is fraught with a high density of post-war stressors that survivors face on a daily basis [4]. Death anxiety becomes a larger concern for the individual when exposed to a traumatic event where he/she is placed in a situation where there is a real threat of harm or death. Death anxiety is a conscious or unconscious psychological state resulting from a defense mechanism that can be triggered when people feel threatened by death [5]. The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association defines death anxiety as a feeling of unsafety, anxiety, or fear related to death or near-death [6]. Death anxiety will become more conscious and can become excessive in the face of death or death experiences. For soldiers, the most common form of this is exposure to war. Soldiers are exposed to the actual harm and fear of death, and the fear becomes heightened because it is no longer just the anticipation of a life-threatening situation or event, this leads to a change in death anxiety overall [7]. Research has shown that Iranian War veterans who have been exposed to death trauma on the battlefield may carry the added burden of unique cognitions and fears related to personal death [8]. Exposure to death and trauma on the battlefield is commonly recognized as a precursor to a posttraumatic stress disorder, but many veterans demonstrate resilience and are able to adjust positively to reentry into civilian life [9].

Cognitive emotion regulation strategies can be considered as one of the variables involved in the death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. This type of emotion regulation is concerned with how individuals manage the intake of information that is emotionally arousing through the use of cognition [10]. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies include processes such as cognitive restructuring, self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, other-blame, acceptance, planning, positive reappraisal, positive-refocusing and putting into perspective [11]. Maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have been proposed to contribute to the maintenance of PTSD [12]. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies except positive refocusing and reappraisal had significant independent main effects on symptoms of depression while only war experiences, self-blame and blaming others had significant main effects on conduct problems in war-affected youth [4]. Higher levels of emotion dysregulation were directed related to higher posttraumatic stress symptom (PTS) severity and lower quality of life (QOL), through more severe negative post-combat worldview and lower coping self-efficacy appraisals [13]. The research of [14] showed that catastrophizing and rumination were associated with more post-traumatic stress symptoms and higher psychological distress. On the other hand, positive reappraisal, refocus on planning, and acceptance was associated with fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms and lower psychological distress.

Another process that warrants examination in connection with the death anxiety of veterans with PTSD is experiential avoidance, defined as rigid behavioral attempts to alter the form, frequency, or intensity of unwanted private events (i.e., thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations) when such behavior impedes valued living [15]. The function of experiential avoidance is to control or minimize the impact of annoying experiences and can provide immediate and short-term relief that negatively reinforces behavior [16]. People who experience more experiential avoidance use more self-destruction, denial, emotional support, behavioral disruption, and self-blame, and experience more intense emotional experiences than pleasant and unpleasant stimuli [17]. A link between experiential avoidance and PTSD symptoms is well established, particularly cross-sectionally [18]. There is a link between negative affectivity, empirical avoidance, cognitive concerns, emotional non-acceptance, and symptoms of PTSD among traumatized individuals [19]. The results of [20] showed that a number of individual difference factors, including emotional distress intolerance, experiential avoidance and anxiety sensitivity, have been implicated in the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptomatology. Experimental avoidance for soldiers with high anxiety sensitivity and anxiety traits is used as an effective short-term strategy and causes PTSD in them [21].

The role of coping self-efficacy with regard to death anxiety appears to tap into a range of skills, beliefs and attitudes about self and death [22]. Self-efficacy is an important proactive “agentic” factor in posttraumatic recovery as well as other psychiatric disorders [23]. Agentic refers to intentionally being an agent of change through one’s actions. One domain-specific measure of self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy (CSE), concerns individuals’ “perceived self-efficacy for coping with challenges or threats” [24]. Self-efficacy plays a proactive role in adaptation to extremely stressful events and thus influences the development of PTSD [25]. Self‐efficacy moderates the relationship between combat exposure and PTSD severity [26]. The research studied the impact of coping skills on death anxiety and PTSD and found that self-efficacy was significantly related to psychiatric comorbidity and death anxiety [22]. On the other hand, a review of death anxiety literature shows self-efficacy is both a predictor and mediator of death anxiety [27].

A review of the research background shows that death anxiety is associated with PTSD and psychiatric comorbidity and coping strategies can impact on these health outcomes, what is not clear is the interrelationship between death anxiety, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, experiential avoidance and coping self-efficacy in veterans with PTSD. It is not clear whether coping self-efficacy would mediate the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance and death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. The impact of death anxiety is an overlooked, yet potentially important component for finding a treatment that focuses on core difficulties and not just the current manifestation of symptoms. On the other hand, war veterans are one of the assets of any society and their psychological problems cannot be ignored. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the causal modeling of death anxiety in veterans with PTSD based on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance with the mediating role of coping self-efficacy. Figure.1 shows the hypothetical model of death anxiety in veterans with PTSD.

Figure 1) Hypothetical model death anxiety in veterans with PTSD

Materials and Methods

The method of the present study is descriptive and structural equations. The statistical population of the present study consisted of all veterans with PTSD who were admitted to Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil in 2019, from which 200 people were selected by the available sampling method. In descriptive research, a sample size for each predictor variable from at least 5 to 40 people has been suggested [28]. In order to increase the external validity and due to the existence of subscales in the predictor variables, 200 people were selected by the available sampling method. At first, the procedure was explained at a meeting with the veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder who were hospitalized and treated in Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil in 2019, and then all ethics, rules, and essential rules have explained to the veterans in a meeting. Then, 200 veterans were selected from all of the interested veterans. Inclusion criteria were: 1) Minimum cycle education; 2) age range 40 to 80 years; 3) Achieving a score higher than the cut-off point in the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PCL-M) checklist; 4) Absence of psychotic symptoms including hallucinations and delusions; 5) Lack of other diagnoses associated with post-traumatic stress disorder; 6) Do not suffer from disorders related to substance abuse. Exclusion criteria: 1) unwillingness to cooperate with the researcher; 2) the questionnaires were incomplete.

At the stage the test, before each one of the tests, the veterans were fully described how to hold and respond, and then they were asked to do the tests. At this stage, veterans have done Templer Death Anxiety Scale, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ) and Coping self-efficacy scale (CSES). Before finishing the tests, we asked the veterans also to provide demographic data including the participant’s age, level of study and job.

In order to ease the responsiveness and uncertainty in responding to the tests, several volunteers reviewed the veterans and made comments about the comprehensibility of the tests. Also, in order to avoid ambiguity during the testing participants during the time of the test, a psychologist guided the veterans in case of having a question, problems in understanding the question, etc.

The method of the present study is descriptive and structural equations. The statistical population of the present study consisted of all veterans with PTSD who were admitted to Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil in 2019, from which 200 people were selected by the available sampling method. In descriptive research, a sample size for each predictor variable from at least 5 to 40 people has been suggested [28]. In order to increase the external validity and due to the existence of subscales in the predictor variables, 200 people were selected by the available sampling method. At first, the procedure was explained at a meeting with the veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder who were hospitalized and treated in Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil in 2019, and then all ethics, rules, and essential rules have explained to the veterans in a meeting. Then, 200 veterans were selected from all of the interested veterans. Inclusion criteria were: 1) Minimum cycle education; 2) age range 40 to 80 years; 3) Achieving a score higher than the cut-off point in the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PCL-M) checklist; 4) Absence of psychotic symptoms including hallucinations and delusions; 5) Lack of other diagnoses associated with post-traumatic stress disorder; 6) Do not suffer from disorders related to substance abuse. Exclusion criteria: 1) unwillingness to cooperate with the researcher; 2) the questionnaires were incomplete.

At the stage the test, before each one of the tests, the veterans were fully described how to hold and respond, and then they were asked to do the tests. At this stage, veterans have done Templer Death Anxiety Scale, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ) and Coping self-efficacy scale (CSES). Before finishing the tests, we asked the veterans also to provide demographic data including the participant’s age, level of study and job.

In order to ease the responsiveness and uncertainty in responding to the tests, several volunteers reviewed the veterans and made comments about the comprehensibility of the tests. Also, in order to avoid ambiguity during the testing participants during the time of the test, a psychologist guided the veterans in case of having a question, problems in understanding the question, etc.

Questionnaires were as follows:

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Military Prescription (PCL-M): This tool consists of 17 items of 5 options based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a diagnostic aid tool by Weathers and Collaborators for the National Center for Post Traumatic Disorder in the United States [29]. 5 articles are related to re-experiencing traumatic symptoms, 7 articles are related to emotional numbness and avoidance symptoms, and the other 5 articles are related to symptoms of severe arousal. The cut-off point for post-traumatic stress disorder is 50. In Iran, it has been standardized [30] that the internal consistency of the questionnaire was 0.93 and in the study[29], the homogeneity coefficient of 0.97 was reported for Vietnam War veterans.

Templer Death Anxiety Scale (TDAS): The TDAS includes 15 items which are scored on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The total score of the scale ranges from 15 to 75. Lower scores indicate lower levels of DA. Items 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 15 are scored in reverse [31]. Research [32] has validated this scale in veterans of Iran–Iraq Warfare. The construct validity of the scale was obtained using exploratory factor analysis that showed four factors with Eigenvalues of greater than 1 and test-retest and internal consistency (total alpha) was 0.91 and 0.89. The reliability of this scale in the present study was 0.79 by Cronbach's alpha method.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire- a short 18-item version (CERQ): Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) is an 18-item tool that measures cognitive emotion regulation strategies in response to the experience of threatening or stressful life events on a five-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always) in terms of 9 subscales: Self-blame; Other Blame; Focus on thought/rumination; Catastrophizing; putting into perspective; Positive refocusing; Positive reappraisal; Acceptance; Refocus on planning. The minimum and maximum scores in each subscale are 6 and 10, respectively, and a higher score indicates more use of that cognitive strategy. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies fall into two general categories: adaptive strategies and maladaptive strategies. The CERQ has been shown to have good factorial validity, good discriminative properties and good construct validity [10]. Cronbach’s alpha of the subscales ranged from 0.62 to 0.85 [10]. In the Persian version of this scale, Cronbach's alpha was obtained in the range of 68 to 82 and it was found that 9 subscales of the CERQ-18 item have good validity [33]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.83.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ): The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire was used to assess EA. Participants respond to 9 items using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=never true to 7=always true). AAQ total scores range from 9–63, with high scores indicating more EA. The AAQ has acceptable internal consistency (αs=0.70-0.86) [34] and demonstrates good concurrent validity with relevant constructs such as thought suppression and mental health symptoms [35]. In Iran, the study [36] examined the psychometric properties of this questionnaire; The results of exploratory factor analysis showed two factors: avoidance of emotional experiences and control over life. Also, the internal consistency and halving coefficient of the questionnaire in different groups was between 0.71-0.89 and satisfactory. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient was 0.89 and the retest reliability coefficient was 0.72. [37] reported the reliability of this questionnaire in the injured people was 0.78. The reliability of this scale in the present study was 0.79 by Cronbach's alpha method.

Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES): Self-efficacy for coping with threats and challenges was assessed using the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale [24]. The measure consists of 26 items rated on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (cannot do at all), 5 (moderately certain can do), to10 (certain can do). Items tap into three subscales: stopping unpleasant emotions and thoughts, using problem-focused coping, and getting support from family and friends, with higher scores indicating greater CSE. Scores can range from 0 to 260. This scale’s total score has exhibited both high internal consistency (α=0.95), and good construct validity, as evidenced by its relation with measures of psychological distress, well-being, and social support [24]. In the Persian version of this scale, the reliability coefficients of the scale factors were obtained by Cronbach's alpha method and the Halving coefficient between 0.63 and 0.91. Also, this scale showed a positive correlation with the general self-efficacy scale [38]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.83.

In order to collect research data, first, an agreement was obtained from the Vice Chancellor for Research of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili stating that data collection and research should be unimpeded. Initially, 200 veterans with PTSD were selected based on inclusion criteria and, if they wished to participate in the study, by available sampling method. Before submitting the questionnaires and collecting information, the sample was individually informed about the objectives and scope of the research, and the necessary communication was established with them. After obtaining written consent from the veterans, the questionnaires were presented to the subjects to complete.

Data analysis was performed using the Pearson correlation test and structural equation using SPSS-23 and Lisrel 8.8 statistical software. Death anxiety was considered as a criterion variable, cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance were considered predictor variables and coping self-efficacy was considered as a mediator variable.

Findings

The statistical sample studied included 200 veterans with PTSD with a mean (standard deviation) of the age of 59.36 (6.74) years. Which ranged in age from 51 to 74 years. 43 (%21.5) of these veterans were single and 157 (%78.5) were married. 58 persons (%29) of education under the diploma and 142 (%71) had a degree of diploma or higher. There were also 72 persons (%36) employees, 79 persons (%39) with a free job and 49 persons (%24.5) unemployed or retired.

According to the obtained results, the mean score of death anxiety in the studied veterans was 7.78±2.73, which was above average level. In terms of the mean score of the variable maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies was equal to 29.82±4.43, which was higher than the mean value according to the cutting point equal to 24. The mean score of the variable adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies was 20.04±5.72 and according to the cutting point (30), it was less than the average value. Also the mean score of the experimental avoidance variable (39.40±11.27), also showed that the experimental avoidance of veterans was higher than the average level. The mean score of the coping self-efficacy variable (80.97±31.88) was lower than the mean value.

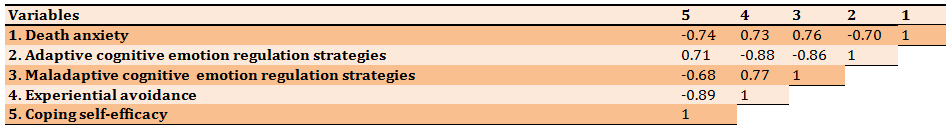

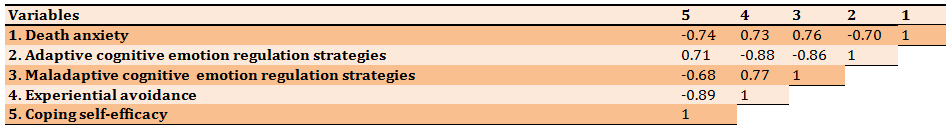

On the other hand, the observed skewness value for the research variables was in the range (-2, 2) that is, in terms of skew, the research variables were normal and their distribution was symmetrical. Also, their Kurtosis value was in the range (-2, 2) this shows the distribution of the variables studied from normal kurtosis. In order to investigate the relationship between research variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used (Table 1).

Based on the results of the correlation matrix (Table 1), there was a negative and significant relationship between the death anxiety with adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and coping self-efficacy (p<0.01), and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance a positive and significant relationship was established (p<0.01). Also, there was a negative and significant relationship between adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with experiential avoidance and a positive and significant relationship with coping self-efficacy (p<0.01). There was a positive and significant relationship between maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance and a negative and significant relationship with coping self-efficacy and finally between experiential avoidance and coping self-efficacy a negative and significant relationship (p<0.01).

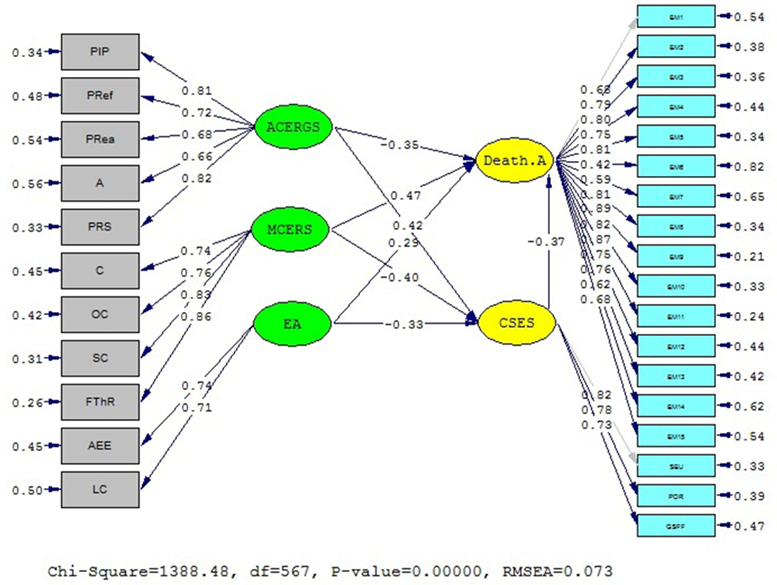

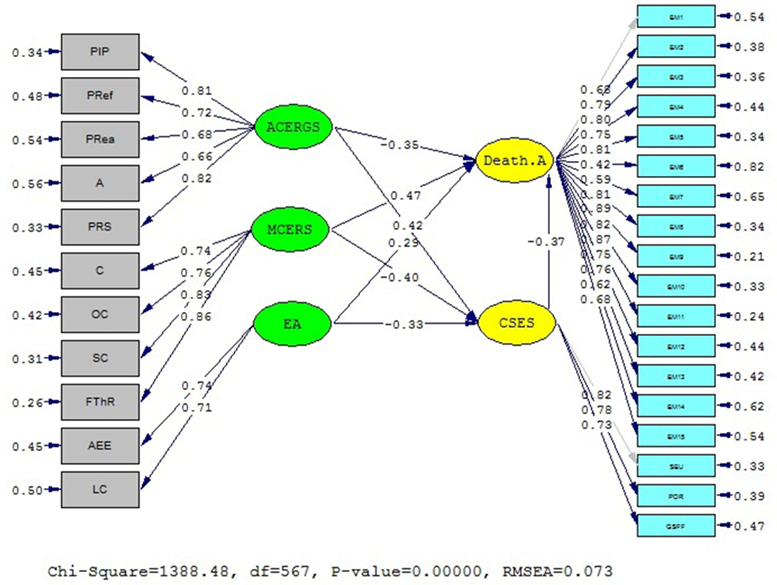

In the following, using structural equations, the direct and indirect effects of adaptive and maladaptive strategies for emotion regulation and experiential avoidance were investigated by mediating coping self-efficacy in combating death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. Figures 2 and 3 show the research model test in standard mode and T value, respectively.

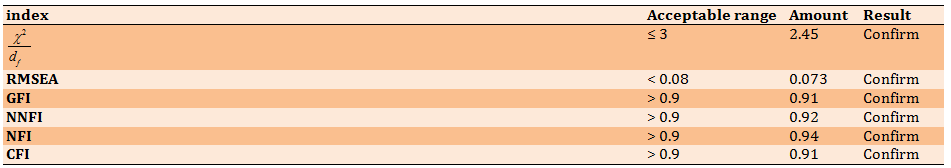

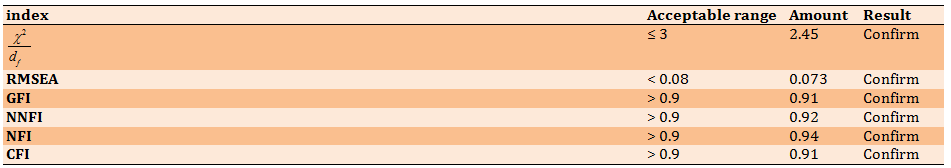

Table 2 shows research model fit indexes. According to the results, we can say that the research model was approved in terms of meaningful and fit indices.

According to Table 3, the direct effect of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies variable on death anxiety was negative and significant, also, adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have a positive and significant direct effect on coping self-efficacy. The direct effect of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies variable and experiential avoidance on death anxiety was positive and significant, and on coping self-efficacy was negative and significant. Finally, the direct effect of the coping self-efficacy variable with death anxiety was negative and significant.

Sobel test has been used to investigate the indirect effect of adaptive and maladaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation and experiential avoidance by mediating coping self-efficacy with death anxiety. It was also used to determine the intensity of the indirect effect through intermediaries called VAF, which provides a value between 0 to 1; and the closer the value was to 1, the greater the effect of the mediator effect. In fact, the amount of indirect effect affects the total effect.

According to the amount of indirect t-statistic (T-Sobel) between the above variables, which was out of range (-1/96 & 1/96), the hypothesis of the indirect effect of adaptive and maladaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation and experimental avoidance on death anxiety was accepted. Therefore, adaptive and maladaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation and experimental avoidance, in addition to the direct effect, indirectly affect death anxiety through coping self-efficacy. Table 4 shows the results of the analysis of the indirect effect.

Based on the amount obtained for VAF statistics it can be explained that %31 of the effects of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies on death anxiety, 24% of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies on death anxiety and 30% of the effect of experimental avoidance on death anxiety through coping self-efficacy can be explained.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Military Prescription (PCL-M): This tool consists of 17 items of 5 options based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a diagnostic aid tool by Weathers and Collaborators for the National Center for Post Traumatic Disorder in the United States [29]. 5 articles are related to re-experiencing traumatic symptoms, 7 articles are related to emotional numbness and avoidance symptoms, and the other 5 articles are related to symptoms of severe arousal. The cut-off point for post-traumatic stress disorder is 50. In Iran, it has been standardized [30] that the internal consistency of the questionnaire was 0.93 and in the study[29], the homogeneity coefficient of 0.97 was reported for Vietnam War veterans.

Templer Death Anxiety Scale (TDAS): The TDAS includes 15 items which are scored on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The total score of the scale ranges from 15 to 75. Lower scores indicate lower levels of DA. Items 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 15 are scored in reverse [31]. Research [32] has validated this scale in veterans of Iran–Iraq Warfare. The construct validity of the scale was obtained using exploratory factor analysis that showed four factors with Eigenvalues of greater than 1 and test-retest and internal consistency (total alpha) was 0.91 and 0.89. The reliability of this scale in the present study was 0.79 by Cronbach's alpha method.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire- a short 18-item version (CERQ): Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) is an 18-item tool that measures cognitive emotion regulation strategies in response to the experience of threatening or stressful life events on a five-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always) in terms of 9 subscales: Self-blame; Other Blame; Focus on thought/rumination; Catastrophizing; putting into perspective; Positive refocusing; Positive reappraisal; Acceptance; Refocus on planning. The minimum and maximum scores in each subscale are 6 and 10, respectively, and a higher score indicates more use of that cognitive strategy. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies fall into two general categories: adaptive strategies and maladaptive strategies. The CERQ has been shown to have good factorial validity, good discriminative properties and good construct validity [10]. Cronbach’s alpha of the subscales ranged from 0.62 to 0.85 [10]. In the Persian version of this scale, Cronbach's alpha was obtained in the range of 68 to 82 and it was found that 9 subscales of the CERQ-18 item have good validity [33]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.83.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ): The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire was used to assess EA. Participants respond to 9 items using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=never true to 7=always true). AAQ total scores range from 9–63, with high scores indicating more EA. The AAQ has acceptable internal consistency (αs=0.70-0.86) [34] and demonstrates good concurrent validity with relevant constructs such as thought suppression and mental health symptoms [35]. In Iran, the study [36] examined the psychometric properties of this questionnaire; The results of exploratory factor analysis showed two factors: avoidance of emotional experiences and control over life. Also, the internal consistency and halving coefficient of the questionnaire in different groups was between 0.71-0.89 and satisfactory. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient was 0.89 and the retest reliability coefficient was 0.72. [37] reported the reliability of this questionnaire in the injured people was 0.78. The reliability of this scale in the present study was 0.79 by Cronbach's alpha method.

Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES): Self-efficacy for coping with threats and challenges was assessed using the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale [24]. The measure consists of 26 items rated on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (cannot do at all), 5 (moderately certain can do), to10 (certain can do). Items tap into three subscales: stopping unpleasant emotions and thoughts, using problem-focused coping, and getting support from family and friends, with higher scores indicating greater CSE. Scores can range from 0 to 260. This scale’s total score has exhibited both high internal consistency (α=0.95), and good construct validity, as evidenced by its relation with measures of psychological distress, well-being, and social support [24]. In the Persian version of this scale, the reliability coefficients of the scale factors were obtained by Cronbach's alpha method and the Halving coefficient between 0.63 and 0.91. Also, this scale showed a positive correlation with the general self-efficacy scale [38]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.83.

In order to collect research data, first, an agreement was obtained from the Vice Chancellor for Research of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili stating that data collection and research should be unimpeded. Initially, 200 veterans with PTSD were selected based on inclusion criteria and, if they wished to participate in the study, by available sampling method. Before submitting the questionnaires and collecting information, the sample was individually informed about the objectives and scope of the research, and the necessary communication was established with them. After obtaining written consent from the veterans, the questionnaires were presented to the subjects to complete.

Data analysis was performed using the Pearson correlation test and structural equation using SPSS-23 and Lisrel 8.8 statistical software. Death anxiety was considered as a criterion variable, cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance were considered predictor variables and coping self-efficacy was considered as a mediator variable.

Findings

The statistical sample studied included 200 veterans with PTSD with a mean (standard deviation) of the age of 59.36 (6.74) years. Which ranged in age from 51 to 74 years. 43 (%21.5) of these veterans were single and 157 (%78.5) were married. 58 persons (%29) of education under the diploma and 142 (%71) had a degree of diploma or higher. There were also 72 persons (%36) employees, 79 persons (%39) with a free job and 49 persons (%24.5) unemployed or retired.

According to the obtained results, the mean score of death anxiety in the studied veterans was 7.78±2.73, which was above average level. In terms of the mean score of the variable maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies was equal to 29.82±4.43, which was higher than the mean value according to the cutting point equal to 24. The mean score of the variable adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies was 20.04±5.72 and according to the cutting point (30), it was less than the average value. Also the mean score of the experimental avoidance variable (39.40±11.27), also showed that the experimental avoidance of veterans was higher than the average level. The mean score of the coping self-efficacy variable (80.97±31.88) was lower than the mean value.

On the other hand, the observed skewness value for the research variables was in the range (-2, 2) that is, in terms of skew, the research variables were normal and their distribution was symmetrical. Also, their Kurtosis value was in the range (-2, 2) this shows the distribution of the variables studied from normal kurtosis. In order to investigate the relationship between research variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used (Table 1).

Based on the results of the correlation matrix (Table 1), there was a negative and significant relationship between the death anxiety with adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and coping self-efficacy (p<0.01), and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance a positive and significant relationship was established (p<0.01). Also, there was a negative and significant relationship between adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies with experiential avoidance and a positive and significant relationship with coping self-efficacy (p<0.01). There was a positive and significant relationship between maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance and a negative and significant relationship with coping self-efficacy and finally between experiential avoidance and coping self-efficacy a negative and significant relationship (p<0.01).

In the following, using structural equations, the direct and indirect effects of adaptive and maladaptive strategies for emotion regulation and experiential avoidance were investigated by mediating coping self-efficacy in combating death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. Figures 2 and 3 show the research model test in standard mode and T value, respectively.

Table 2 shows research model fit indexes. According to the results, we can say that the research model was approved in terms of meaningful and fit indices.

According to Table 3, the direct effect of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies variable on death anxiety was negative and significant, also, adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have a positive and significant direct effect on coping self-efficacy. The direct effect of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies variable and experiential avoidance on death anxiety was positive and significant, and on coping self-efficacy was negative and significant. Finally, the direct effect of the coping self-efficacy variable with death anxiety was negative and significant.

Sobel test has been used to investigate the indirect effect of adaptive and maladaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation and experiential avoidance by mediating coping self-efficacy with death anxiety. It was also used to determine the intensity of the indirect effect through intermediaries called VAF, which provides a value between 0 to 1; and the closer the value was to 1, the greater the effect of the mediator effect. In fact, the amount of indirect effect affects the total effect.

According to the amount of indirect t-statistic (T-Sobel) between the above variables, which was out of range (-1/96 & 1/96), the hypothesis of the indirect effect of adaptive and maladaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation and experimental avoidance on death anxiety was accepted. Therefore, adaptive and maladaptive strategies of cognitive emotion regulation and experimental avoidance, in addition to the direct effect, indirectly affect death anxiety through coping self-efficacy. Table 4 shows the results of the analysis of the indirect effect.

Based on the amount obtained for VAF statistics it can be explained that %31 of the effects of adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies on death anxiety, 24% of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies on death anxiety and 30% of the effect of experimental avoidance on death anxiety through coping self-efficacy can be explained.

Table 1) Correlation matrix of variables (p<0.01)

Figure 2) Research model test (In Standard Mode)

Figure 3) Research model test (T value)

Table 2) Research model fit indexes

Table 3) Structural equations of the research model (p<0.05)

Table 4) Results of indirect effects analysis

Figure 2) Research model test (In Standard Mode)

Figure 3) Research model test (T value)

Table 2) Research model fit indexes

Table 3) Structural equations of the research model (p<0.05)

Table 4) Results of indirect effects analysis

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the causal modeling of death anxiety in veterans with PTSD based on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance with the mediating role of coping self-efficacy.

The results showed that adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have a negative and significant direct effect and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have a positive and significant direct on death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with the results of research [4, 12, 14]. To explain these findings, it can be argued that when confronted with stressful situations, cognitive emotion regulation strategies help individuals make sense of strong emotions following stressful or traumatic events [10]. Veterans with PTSD who use adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies experience lower levels of anxiety. In other words, the negative association between adaptive cognitive regulation strategies and death anxiety can be attributed to the veterans’ ability to change her view in the face of stressful events and pay attention to the positive and long-term outcomes, which in turn decreases the level of stress and helps the veterans to reframe the events to accept what cannot be controlled, which results in reduced stress. In contrast, those who employ maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation experience higher levels of anxiety, through hasty reactions, instead of using appropriate methods. The source of stress can be recognized by applying efficient emotion regulation strategies; that result in increased self-esteem and self-confidence as well as reduced anxiety and distress associated with PTSD.

The results showed that experiential avoidance has a positive and significant direct on death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with the results of research [18, 20, 21]. Experiential avoidance appears to promote PTSD when it is applied inflexibly and across situations [18]. Traumatic exposure can bring about strong, painful emotions and memories that are difficult to reconcile with previous experiences. When an individual is exposed to trauma, they may engage in more EA due to the presence of posttraumatic symptoms (e.g., intrusive memories and nightmares), but those who naturally recover may oscillate between processing and avoidance. Over time, those who oscillate facilitate the integration of new information, and the emotional intensity may subside, leading to recovery; the maladaptive reliance on EA in those who go on to develop PTSD may inhibit this process. On the other hand, death anxiety can be heightened following exposure to traumatic life events or the development of posttraumatic stress disorder [22]. Therefore, veterans with PTSD who exercise experiential avoidance flexibly will experience less death anxiety.

The results showed that coping self-efficacy has a negative and significant direct on death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with the results of research of [22]. In explaining this finding, we can say that based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory, perceived self-efficacy to exercise control over potential threats plays a central role in anxiety arousal [39]. People’s self-efficacy includes a sense of competency in relation to death; low competency results in high death anxiety and vice versa [22]. In other words, self-efficacy is used as a buffer mechanism against death anxiety and it includes a sense of competency in general and can be applied to death anxiety. Hence, veterans with PTSD who have high coping self-efficacy suffer less from death anxiety.

The results also showed that coping self-efficacy can mediate the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. No research has been found that is directly consistent with these results, but there are studies from which such results can be inferred. Higher levels of emotion dysregulation were directed related to higher posttraumatic stress symptom (PTS) severity and lower quality of life (QOL), through more severe negative post-combat worldview and lower coping self-efficacy appraisals [13]. CSE acted as a mediator between acute stress response and both PTSD symptoms and global distress [23]. Based on the social-cognitive theory of post-traumatic recovery, the agentic adaptation model can be used to demonstrate the mediational role of coping self-efficacy between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. This theory has its roots in an agentic perspective that views people as self-organizing, proactive, self-reflecting and self-regulating, not just as reactive organisms shaped by traumatic forces or driven by inner pathology [23]. Coping self-efficacy refers to individuals’ beliefs in their ability to cope with emotions and stressful events; it can be concluded that the coping self‐efficacy leads to the regulation of cognitive or positive assessments of their environment. So, in veterans with PTSD, the coping self-efficacy between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and death anxiety has a mediating role.

Finally, the results showed that coping self-efficacy can mediate the relationship between experiential avoidance and death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. No research has been found that is directly consistent with these results, but there are studies from which such results can be inferred [26, 27]. Analyses of the causal structure of self-protective behavior show that anxiety arousal and avoidant behavior are mainly co-effects of perceived coping inefficacy [23]. Those who have high levels of experiential avoidance prior to traumatic exposure may continue to rely on experiential avoidance in a maladaptive manner to cope with the trauma, hindering natural recovery, whereas those with lower levels of experiential avoidance pre-trauma may not rely on experiential avoidance rigidly and naturally recover.

This study is limited to veterans with PTSD in Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil. In generalizing the results, caution should be observed. This research is conducted in a correlational manner, based on which it is not possible to explain the causal relationship, so we must be careful in interpreting the results, and also that this research has been done only quantitatively if there is a change in research objectives. It made it possible to use qualitative methods such as in-depth and semi-structured interviews; more complete results were obtained; Therefore, it is suggested that this research be conducted in other regions of the country and on more samples.

Also, according to the research findings, it is suggested that the results of this study be used in psychiatric hospitals to decrease the death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. It is recommended that courses in coping self-efficacy and adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and improvement of experiential avoidance be conducted as training workshops in psychiatric hospitals.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings of this study showed that coping self-efficacy as a mediating variable could explain the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies, experiential avoidance, and death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and coping self-efficacy of veterans reduce death anxiety in them.

Acknowledgments: Finally, the authors of this article would like to express their gratitude for the cooperation of the dear veterans of Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil, as well as the support of the officials of the Martyrs and Veterans Affairs Foundation of Ardabil.

Ethical Permissions: This work was done individually and in case of any ambiguity while completing the questionnaires, the necessary instructions were provided to the subject in the framework of how to implement the relevant questionnaires. In addition ensuring the confidentiality of the information and preparing people for the research sample to participate in the research was one of the ethical points of this research. Also, common codes of ethics in medical research include 14, 13, 2 (benefits from the findings for the advancement of human knowledge), code 20 (coordination of research with religious and cultural standards) and codes 1, 3, 24 (satisfaction Subjects and his legal representative) have been observed in this research.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Eyni S (First Author), Main Researcher (50%); Hashemi Z (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Ebadi M (Third Author), Article Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

The aim of this study was to investigate the causal modeling of death anxiety in veterans with PTSD based on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and experiential avoidance with the mediating role of coping self-efficacy.

The results showed that adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have a negative and significant direct effect and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies have a positive and significant direct on death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with the results of research [4, 12, 14]. To explain these findings, it can be argued that when confronted with stressful situations, cognitive emotion regulation strategies help individuals make sense of strong emotions following stressful or traumatic events [10]. Veterans with PTSD who use adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies experience lower levels of anxiety. In other words, the negative association between adaptive cognitive regulation strategies and death anxiety can be attributed to the veterans’ ability to change her view in the face of stressful events and pay attention to the positive and long-term outcomes, which in turn decreases the level of stress and helps the veterans to reframe the events to accept what cannot be controlled, which results in reduced stress. In contrast, those who employ maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation experience higher levels of anxiety, through hasty reactions, instead of using appropriate methods. The source of stress can be recognized by applying efficient emotion regulation strategies; that result in increased self-esteem and self-confidence as well as reduced anxiety and distress associated with PTSD.

The results showed that experiential avoidance has a positive and significant direct on death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with the results of research [18, 20, 21]. Experiential avoidance appears to promote PTSD when it is applied inflexibly and across situations [18]. Traumatic exposure can bring about strong, painful emotions and memories that are difficult to reconcile with previous experiences. When an individual is exposed to trauma, they may engage in more EA due to the presence of posttraumatic symptoms (e.g., intrusive memories and nightmares), but those who naturally recover may oscillate between processing and avoidance. Over time, those who oscillate facilitate the integration of new information, and the emotional intensity may subside, leading to recovery; the maladaptive reliance on EA in those who go on to develop PTSD may inhibit this process. On the other hand, death anxiety can be heightened following exposure to traumatic life events or the development of posttraumatic stress disorder [22]. Therefore, veterans with PTSD who exercise experiential avoidance flexibly will experience less death anxiety.

The results showed that coping self-efficacy has a negative and significant direct on death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. This finding is consistent with the results of research of [22]. In explaining this finding, we can say that based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory, perceived self-efficacy to exercise control over potential threats plays a central role in anxiety arousal [39]. People’s self-efficacy includes a sense of competency in relation to death; low competency results in high death anxiety and vice versa [22]. In other words, self-efficacy is used as a buffer mechanism against death anxiety and it includes a sense of competency in general and can be applied to death anxiety. Hence, veterans with PTSD who have high coping self-efficacy suffer less from death anxiety.

The results also showed that coping self-efficacy can mediate the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. No research has been found that is directly consistent with these results, but there are studies from which such results can be inferred. Higher levels of emotion dysregulation were directed related to higher posttraumatic stress symptom (PTS) severity and lower quality of life (QOL), through more severe negative post-combat worldview and lower coping self-efficacy appraisals [13]. CSE acted as a mediator between acute stress response and both PTSD symptoms and global distress [23]. Based on the social-cognitive theory of post-traumatic recovery, the agentic adaptation model can be used to demonstrate the mediational role of coping self-efficacy between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. This theory has its roots in an agentic perspective that views people as self-organizing, proactive, self-reflecting and self-regulating, not just as reactive organisms shaped by traumatic forces or driven by inner pathology [23]. Coping self-efficacy refers to individuals’ beliefs in their ability to cope with emotions and stressful events; it can be concluded that the coping self‐efficacy leads to the regulation of cognitive or positive assessments of their environment. So, in veterans with PTSD, the coping self-efficacy between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and death anxiety has a mediating role.

Finally, the results showed that coping self-efficacy can mediate the relationship between experiential avoidance and death anxiety in veterans with PTSD. No research has been found that is directly consistent with these results, but there are studies from which such results can be inferred [26, 27]. Analyses of the causal structure of self-protective behavior show that anxiety arousal and avoidant behavior are mainly co-effects of perceived coping inefficacy [23]. Those who have high levels of experiential avoidance prior to traumatic exposure may continue to rely on experiential avoidance in a maladaptive manner to cope with the trauma, hindering natural recovery, whereas those with lower levels of experiential avoidance pre-trauma may not rely on experiential avoidance rigidly and naturally recover.

This study is limited to veterans with PTSD in Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil. In generalizing the results, caution should be observed. This research is conducted in a correlational manner, based on which it is not possible to explain the causal relationship, so we must be careful in interpreting the results, and also that this research has been done only quantitatively if there is a change in research objectives. It made it possible to use qualitative methods such as in-depth and semi-structured interviews; more complete results were obtained; Therefore, it is suggested that this research be conducted in other regions of the country and on more samples.

Also, according to the research findings, it is suggested that the results of this study be used in psychiatric hospitals to decrease the death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. It is recommended that courses in coping self-efficacy and adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and improvement of experiential avoidance be conducted as training workshops in psychiatric hospitals.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings of this study showed that coping self-efficacy as a mediating variable could explain the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies, experiential avoidance, and death anxiety of veterans with PTSD. Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and coping self-efficacy of veterans reduce death anxiety in them.

Acknowledgments: Finally, the authors of this article would like to express their gratitude for the cooperation of the dear veterans of Isar Psychiatric Hospital in Ardabil, as well as the support of the officials of the Martyrs and Veterans Affairs Foundation of Ardabil.

Ethical Permissions: This work was done individually and in case of any ambiguity while completing the questionnaires, the necessary instructions were provided to the subject in the framework of how to implement the relevant questionnaires. In addition ensuring the confidentiality of the information and preparing people for the research sample to participate in the research was one of the ethical points of this research. Also, common codes of ethics in medical research include 14, 13, 2 (benefits from the findings for the advancement of human knowledge), code 20 (coordination of research with religious and cultural standards) and codes 1, 3, 24 (satisfaction Subjects and his legal representative) have been observed in this research.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' Contribution: Eyni S (First Author), Main Researcher (50%); Hashemi Z (Second Author), Assistant Researcher/Statistical Analyst (25%); Ebadi M (Third Author), Article Writer (25%)

Funding/Support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Keywords:

References

1. Vahia V.N. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(3):220-3 [Link] [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.117131]

2. Muller J, Ganeshamoorthy S, Myers J. Risk factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in US veterans: A cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181647. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0181647]

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 10th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Link]

4. Amone-P′Olak K, Stochl J, Ovuga E, Abbott R, Meiser-Stedman R, Croudace TJ, et al. Postwar environment and long-term mental health problems in former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: the WAYS study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(5):425-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/jech-2013-203042]

5. Kesebir P. A quiet ego quiets death anxiety: humility as an existential anxiety buffer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106(4):610-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0035814]

6. Malinauskaite I, Slapikas R, Courvoisier D, Mach F, Gencer B. The fear of dying and occurrence of posttraumatic stress symptoms after an acute coronary syndrome: a prospective observational study. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(2):208-17. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1359105315600233]

7. Kibble CJ. The relationship between death anxiety and combat-related stress. J Hosp Med Manage. 2019;5(1):2. [Link]

8. Sharif Nia H, Ebadi A, Lehto RH, Peyrovi H. The experience of death anxiety in Iranian war veterans: A phenomenology study. Death Stud. 2015;39(1-5):281-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2014.991956]

9. Pietrzak RH, Cook JM. Psychological resilience in older U.S. veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(5):432-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/da.22083]

10. Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire - development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Pers Individ Differ. 2006;41(6):1045-53. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010]

11. Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Pers Individ Diff. 2001;30(8):1311-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6]

12. Kaczkurkin AN, Zang Y, Gay N, Peterson AL, Yarvis JS, Borah EV, et al. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies associated with the DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30(4):343-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jts.22202]

13. Smith AJ, Holohan DR, Jones RT. Emotion regulation difficulties and social cognitions predicting PTSD severity and quality of life among treatment seeking combat veterans. Mil Behav Health. 2019;7(1):73-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/21635781.2018.1540314]

14. Min D, Lee SH. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies in post-traumatic stress disorder. Mood Emot. 2019;17(1):1-11. [Link]

15. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. 2nd edition. The Guilford Press; 2012. [Link]

16. Eifert GH, Forsyth JP, Arch J, Espejo E, Keller M, Langer D. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety disorders: Three case studies exemplifying a unified treatment protocol. Cogn Behav Pract. 2009;16(4):368-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.001]

17. Karekla M, Panayiotou G. Coping and experiential avoidance: Unique or overlapping constructs?. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42(2):163-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.10.002]

18. Seligowski AV, Lee DJ, Bardeen JR, Orcutt HK. Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2015;44(2):87-102. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2014.980753]

19. Bakhshaie J, Zvolensky MJ, Allan N, Vujanovic AA, Schmidt NB. Differential effects of anxiety sensitivity components in the relation between emotional non-acceptance and post-traumatic stress symptoms among trauma-exposed treatment-seeking smokers. Cogn Behav Ther. 2015;44(3):175-89. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/16506073.2015.1004191]

20. Bardeen JR, Fergus TM. Emotional distress intolerance, experiential avoidance, and anxiety sensitivity: the buffering effect of attentional control on associations with posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38:320-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s10862-015-9522-x]

21. Cobb AR, Lancaster CL, Meyer EC, Lee HJ, Telch MJ. Pre-deployment trait anxiety, anxiety sensitivity and experiential avoidance predict war-zone stress-evoked psychopathology. J Context Behav Sci. 2017;6(3):276-87. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.05.002]

22. Hoelterhoff M, Chung MC. Self-efficacy as an agentic protective factor against death anxiety in PTSD and psychiatric co-morbidity. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(1):165-81. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11126-019-09694-5]

23. Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(10):1129-48. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008]

24. Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 3):421-37. [Link] [DOI:10.1348/135910705X53155]

25. Hirschel MJ, Schulenberg SE. Hurricane Katrina's impact on the Mississippi Gulf Coast: General self-efficacy's relationship to PTSD prevalence and severity. Psychol Serv. 2009;6(4):293-303. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/a0017467]

26. Blackburn L, Owens GP. The effect of self-efficacy and meaning in life on posttraumatic stress disorder and depression severity among veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2015;17(3):219-28. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22133]

27. Fry PS. Perceived self-efficacy domains as predictors of fear of the unknown and fear of dying among older adults. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):474-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.474]

28. Delavar A. Theoretical and practical research in the humanities and social sciences. Tehran: Roshd Press; 2017. [Persian] [Link]

29. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane T. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Hisser Studies San Antonio. Unknown publisher; 1993. [Link]

30. Goodarzi MA. Reliability and validity of post- traumatic stress disorder Mississippi scale. J Psychol. 2003;7(2):135-78. [Persian] [Link]

31. Templer DI. The construction and validation of a death anxiety scale. J Gen Psychol. 1970;82(2d Half):165-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/00221309.1970.9920634]

32. Sharif Nia H, Lehto RH, Ebadi A, Peyrovi H. Death anxiety among nurses and health care professionals: A review article. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2016;4(1):2-10. [Link]

33. Hasani J. The reliability and validity of the short form of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. J Res Behav Sci. 2011;9(4):229-40. [Persian] [Link]

34. Arch JJ, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Eifert GH, Craske MG. Longitudinal treatment mediation of traditional cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(7-8):469-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.007]

35. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. Psychol Record. 2004;54(4):553-78. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/BF03395492]

36. Abbasi I, Fati L, Moludi R, Zarrabi H. Psychometric properties of Persian version of acceptance and action questionnaire-II. J Psychol Models Methods. 2013;3(10):65-80. [Persian] [Link]

37. Basharpoor S, Shafiei M, Atadokht A, Narimani M. The role of experiential avoidance and mindfulness in predicting the symptoms of stress disorder after exposure to trauma in traumatized people supported by Emdad Committee and Bonyade Shahid organization of Gilan Gharb in the First half of 2014. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2015;14(5):405-16. [Persian] [Link]

38. Bahramiyan H, Morovati Z, Yousefi M, Amiri M. Reliability, validity, and factorial analysis of coping self-efficacy scale. Clin Psychol Pers. 2017;15(2):215-26. [Persian] [Link]

39. Butler G. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Br J ClinPsychol Leicester.1998;37(4):470. [Link]