Volume 14, Issue 1 (2022)

Iran J War Public Health 2022, 14(1): 37-42 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/10/12 | Accepted: 2022/03/9 | Published: 2022/03/5

Received: 2021/10/12 | Accepted: 2022/03/9 | Published: 2022/03/5

How to cite this article

Mahdavitaree R, Esmaeili R, Mousavi B, Fani M. Effect of Spiritual-Religious Practice on Health and Life Satisfaction of War Survivors Hospitalized due to COVID-19. Iran J War Public Health 2022; 14 (1) :37-42

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1042-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1042-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Medical-Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Prevention Department, Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Islamic Education, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Medical-Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Prevention Department, Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Islamic Education, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text (HTML) (279 Views)

Introduction

Iran has witnessed profound effects on the mental health and well-being of soldiers and war survivors since the war. The war had many consequences on the economic, social, and cultural aspects. On the other hand, many war survivors are middle-aged or elderly, who in addition to the numerous problems caused by the war, also experience a number of other physiological changes, for example, changes in the physical-psychological systems [1]. According to studies, war survivors are divided into three groups: psychiatric war survivors, chemical war survivors, and war survivors with traumatic injuries [2].

The rapid changes in societies have led to changes in factors affecting human health (physical, chemical, biological and social factors). This development, in turn, has led to serious changes in the pattern of diseases, which necessitates the recognition and application of new methods, especially holistic. In parallel with these changes, the increasing use of new methods in medicine is evident. One of these methods, which has recently been considered scientifically in the world, is the spiritual-religious practice [3]. Studies have shown that when faced with a chronic illness, many people turn to their spirituality and religious beliefs. Research has also shown that people who are medically ill often use spiritual and religious practices to cope with their illness [4]. Spiritual care is necessary not only for people with religious beliefs but also for all people. Nursing researches show that the spiritual dimension is one of the most important aspects of nursing in caring for and relieving patients' pain [5]. At the end of December 2019, the spread of a new infectious disease was reported in China, caused by a new coronavirus and officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization. This virus has infected Iran, like other countries in the world [6]. The most common symptoms of this disease include fever, cough, and pulmonary involvement, which are sometimes accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms. Pulmonary damage also causes fibrosis of lung tissue, difficulty breathing, and decreased arterial oxygen levels [7]. Quality of life, which is one of the most important components of mental health, is a multidimensional and mental concept that originates from people's beliefs and perceptions. This multidimensional and mental concept not only reflects the individual's assessment of his or her environment, but also includes physical health, psychological state, autonomy, social relationships, and personal and spiritual beliefs [8]. Quality of life can be considered as the relationship between a person's health status on the one hand and the ability to pursue life goals on the other hand [9]. Since the concept of quality of life is one of the important concepts of life that is directly related to the concept of life satisfaction, so the awareness of the care team and nurses of the concept, dimensions, and factors of quality of life is one way to improve quality of life and patient satisfaction. Paying attention to improving the quality of life is an important key to community health [10].

Life satisfaction is the evaluation of the quality of life based on selected individual criteria and if the living conditions are in line with individual criteria, life satisfaction will be higher [11]. In theoretical concepts, the issue of life satisfaction is mentioned as one of the necessary conditions for the effective psychological functioning of a human being. According to the World Health Organization, the four factors that directly affect life satisfaction are physical health, mental health, social relationships, and the environment. Life satisfaction is essential for the overall quality of life [12]. One researcher believes that people who are more satisfied with their life use more effective and appropriate coping methods, experience deeper positive emotions, and have a higher quality of life [13]. Many studies have shown that the categories of life satisfaction and happiness are directly related to religious beliefs and behaviors [14].

Considering the importance and potential role of spiritual-religious practice as a complementary approach in health promotion, this study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of spiritual-religious practice on the quality of life and life satisfaction of hospitalized war survivors with COVID-19.

Materials & Methods

In this quasi-experimental clinical trial, the effect of spiritual-religious practice on the quality of life and life satisfaction of war survivors with COVID-19 admitted to Sasan Hospital in Tehran in 2021 was performed. Sampling was done by convenience sampling and division into intervention and random control groups. The number of samples was 67 in each group, due to the possibility of sample loss of 10% has been added to the samples (a total of 150 cases). War survivors were divided into two groups of 75 in the intervention and control groups. All participants in the pre-admission study were evaluated for vital signs and para clinics in terms of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were being a war survivor, hospitalization due to COVID-19 disease with a positive PCR test, alertness and those were having any clinical condition such as diagnosed mental problems, drowsiness and confusion, depression, and condition that affected a person's ability to participate in the study, patients admitted to the ICU or died within the first 48 hours of the study were excluded from the study.

Demographic information, history of diseases, and risk factors were assessed at the beginning of the study. Risk factors assessed in the study included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, immune deficiency, malignancy or chemotherapy, hyperlipidemia, organ transplants, AIDS, BMI higher than 40, and recently corticosteroid use. 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) and Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) questionnaires were used to determine the quality of life and life satisfaction scores. The SF-12 questionnaire was developed in 1996 by War-Kasinski and Keller. This questionnaire has 8 subscales that determine the dimensions of quality of life during the last four weeks. These eight dimensions include physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, emotional role, vitality, and mental health. Some questions were answered using yes and no and others in five-point Likert. The score is 12-48. A score of 12-24 indicates a poor quality of life, a score of 25-36 indicates an average quality of life, and a score of 37-48 indicates a good quality of life. So a higher score indicates a better quality of life [15]. Montazeri et al. examined the validity of this questionnaire in Iran. Samples in this study were randomly selected from people aged 15 and over who lived in Tehran. Reliability was assessed using internal consistency and validity was assessed using known group control and convergent validity. Cronbach's alpha was 0.73 for the physical component summary and 0.72 for the psychological component summary. Finally, the findings showed that SF12 is a valid measure of health-related quality of life among the Iranian people [15]. Diner et al. developed a life satisfaction scale for all age groups. The scale consisted of 48 questions that reflected life satisfaction and well-being. 10 questions were related to life satisfaction, which after several studies was finally reduced to 5 questions and used as a separate scale. Questions are answered in a five-point Likert from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Scoring is between 5 and 25. A higher score indicates higher life satisfaction. To determine the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Iran, 109 students of Islamic Azad University, completed this questionnaire. The validity of the Life Satisfaction Scale was 0.83 using the Cronbach's alpha method and 0.69 using the retest method [16].

This research was approved by School of Nursing & Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The aims of the study were explained to eligible war survivors. After providing complete information about the aims of the study, informed consent was obtained from all participants. In this study, the patient's usual medical treatments were continued according to the physician's instructions and there was no interruption. Participants also had the right to be excluded from the study if they wanted, and it was ensured that there would be no restrictions on receiving the required medical services. The participants received their usual treatment protocol according to the instructions ordered by their physicians, who were independent of the research team. The spiritual-religious practice intervention was performed by the war survivor himself with the intention of healing and recovery so that the war survivors prayed for themselves and since they were aware of the intervention, it was not possible to blind them and the data analysis was analyzed by the researcher (single-blinded). War survivors were asked to recite “Surah Al-Hamd” and “Ya Allah” for the sake of healing and recovery. The duration of the intervention was seven days (from the beginning of hospitalization in Sasan Hospital in March and April 2021) three times a day for 5 minutes each time, which included a total of 21 interventions sessions- spiritual-religious practice with three times “Surah Al-Hamd” and then 66 times “YaAllah”. Intervention times were considered with the patient's medication (approximately every 8 hours). War survivors in the intervention group (75 people) were given a registration form for spiritual-religious practice and were asked to check the registration form by checking each time. Participants were taught how to record data on spiritual-religious practice. During the 7-day intervention period, at the beginning of each day, the intervention record was checked and also remind of the spiritual practices. War survivors who had practiced less than 15 times were excluded from the study.

The data were analyzed by SPSS 20. First, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov quantitative data normality test was performed and parametric tests were used to analyze the data of variables with normal distribution. Data analysis was analyzed using Chi-square, independent t-test, and Fisher's exact test. GEE analysis was used to determine factors that are independently related to the quality of life and life satisfaction.

Findings

Of the 183 war survivors who met the inclusion criteria, 153 war survivors were reluctant to participate in the study (Participation rate: 81.9%). The data of war survivors done religious spiritual care more than 15 times were analyzed (and the data with less than15 times were excluded from the study (%1.6)). The total data of 150 war survivors who completed the intervention are presented in this study. The mean age of participants was 56.48±4.74, and 56.48±4.74 in the intervention and control groups, respectively (p=0.64). Also, the mean war survivor disability rate was 14.16±11.646, and 16.09±15.56 in the intervention and control groups, respectively (p=0.39). Most participants in both intervention and control groups were male, married, unemployed, and above Diploma (Table 1).

There were no significant differences between the two groups in all dimensions at the beginning of the study (p>0.05). The differences between before and after the intervention were significant in the intervention group in the following dimensions: physical functioning; role physical; mental health; social functioning; bodily pain; general health; mental Component Summary and Physical Component Summary (p<0.05). The differences in physical function, role physical, social functioning, bodily pain, general health, mental Component summary, and physical component summary were significant in the control group between before and at the end of the study, as well (p<0.05; Table 2).

Table 1) Results of demographic and clinical features in hospitalized war survivors with COVID-19 before the intervention

Table 2) Mean results of quality of life score in war survivors admitted with COVID-19 in two groups at the beginning and end of the study

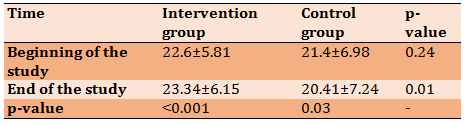

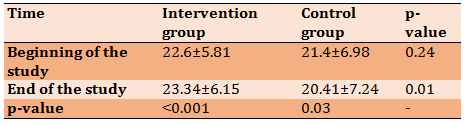

There were no significant differences between the two groups at the beginning of the study (p>0.05). The mean score of life satisfaction was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group. At the end of the study, the scores of life satisfaction had significant differences in the intervention and control groups (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 3) Comparison of the mean and standard deviation of life satisfaction scores in war survivors hospitalized with COVID-19 before and after intervention

The mean differences between the two groups showed that role of physical and Physical Component Summary had significantly increased in the intervention group who have spiritual practice (Table 4).

Table 4) Comparison of the mean±SD difference in the quality of life and life satisfaction between two groups

Discussion

This study showed that spiritual-religious practice with healing intentions improved role physical, Physical Component Summary, and life satisfaction among war survivors hospitalized due to COVID-19.

Spiritual care hasn’t found its proper position in the care setting of Iran yet, and members of the healthcare team do not have sufficient training to provide this kind of care [17]. However Spiritual care is important in nursing practice, and spiritual well-being and spiritual care are associated with better health [18].

Currently, the use of complementary and alternative medicines in COVID-19 seems to be a common practice all over the world. Limited research exists from human clinical trials regarding the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicines in COVID-19. Several clinical trials on complementary and alternative medicines have been registered in the Middle-east such as Meditation or holy Quran recitation, cupping therapy (Hijama), acupuncture, massage, specific nutritional tonics, and herbs such as honey, dates, figs, peaches, garlic, olives, Anthemis hyaline (chamomile) and black cumin seeds [19].

In recent decades, much scientific research has been done on the impact of spiritual care on health improvement. The results of most studies indicated that spiritual care had a potential beneficial effect on the quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness [20].

In our study most participants had risk factors and the most important risk factors were blood pressure and diabetes, which the rate was similar to the other studies [21-25]. The desire to pray is a natural feeling and spiritual care is a basic need in human beings. Many people pray when they are sick, but the clinical effects of spiritual care are not well understood [26]. The results of Mazandarani et al.'s study showed that Spiritual counseling provides self-efficacy, self-control, and daily self-calculation in patients and improves the quality of life (in emotional function) in patients [27]. A study on spiritual health in war survivors showed that there is a direct relationship between spiritual health and general health and quality of life (there were significant differences between spiritual health and physical functioning and bodily pain). This study revealed that higher spiritual health is accompanied by a better quality of life and general health [28]. The other study investigates the relationship between spirituality and life satisfaction among patients with spinal cord injury. Data analysis indicated that there was a significant positive correlation between life satisfaction and psychological/spiritual factors of the quality of life [29].

Different studies used a variety of Quranic recitations to practice spiritual healing including Surah “Al-Hamd”; “Altowhid”; “Alqadr” and “YaAllah recitation” for the sake of healing and recovery [30-34]. Farzin Ara et al.'s study showed that “Ya Allah” reduced the patients’ pain after orthopedic surgery [30]. Also in the study of Etefagh et al., reciting the “Surah Alhamd” “Surah Altowhid” and “Surah Alqadr” reduced the severity of clinical symptoms in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome [31]. In Forouhari et al.'s study, the effect of Quran sound on labor pain was investigated. The results of this study showed that listening to the Quran is a complementary method to reduce labor pain in nulliparous women [32]. Hassanpour et al. investigated the effect of Hazrat Zahra’s praises recitations on the pain. The results showed that reciting Hazrat Zahra’s praises reduced pain severity in hospitalized patients [33]. Another study on the effect of the Holy Quran on pain due to heel-stick showed that there was no significant difference between the pain of the patients before and after the intervention [34].

Bartlett et al. find that spiritual transcendence such as reading the bible and praying frequently as is independently associated with happiness psychological health, subjective well-being, and life satisfaction [35]. However, spirituality and religious beliefs were better predictors of happiness and quality of life for Protestants and Catholics than Jews [36].

The main barriers to spiritual care are the difficulty in defining spirituality; lack of palliative care departments; lack of clear guidelines for the nurse's role in providing spiritual care and nurses' lack of time and high workloads to provide spiritual care [17, 18]. Also in this study, most participants were male and the age range of most of them in both groups was 55-64 years because of choosing war survivors for this study. Therefore, the impact of the intervention on women as well as other age groups needs further investigation. Another limitation in this study was that patients with COVID-19 were unable to participate in spiritual-religious practice due to weakness and lethargy.

Conclusion

People who are medically ill often use spiritual and religious practices to cope with their illness. Spiritual care is necessary not only for people with religious beliefs but also for all people. As the World Health Organization confirmed spiritual health is an important dimension of health on which health can be enjoyed and is an important base for other dimensions of health. This study showed that spiritual-religious practice with healing intentions in addition to routine medical treatments improved role physical, Physical Component Summary, and life satisfaction among war survivors hospitalized due to COVID-19. However, more research is needed to clarify the various dimensions recommended.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express my deep thanks to all war survivors enrolled in the current study for their kind cooperation to complete the present trial; and Dr. Marziyeh Asgari, Mrs Bajouli and Dr. Zohreh Ganjparvar who have contributed to the various stages of the present study. The authors are grateful for the guidance and spiritual support of the honorable master Akram Jahangir throughout the study.

Ethical Permissions: This research was approved with the ethics code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1400.006 and Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials code IRCT20210227050517N1.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflict of interest was reported.

Authors’ Contribution: Mahdavi R (First Author), Main Researcher (25%); Esmaeili R (Second Author), Discussion Writer (25%); Mousavi B (Third Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Fani M (Forth Author), Assistant Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: The present study was extracted from the master thesis by Raheleh Mahdavi in Sasan hospital and was conducted with the financial support of School of Nursing & Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Iran has witnessed profound effects on the mental health and well-being of soldiers and war survivors since the war. The war had many consequences on the economic, social, and cultural aspects. On the other hand, many war survivors are middle-aged or elderly, who in addition to the numerous problems caused by the war, also experience a number of other physiological changes, for example, changes in the physical-psychological systems [1]. According to studies, war survivors are divided into three groups: psychiatric war survivors, chemical war survivors, and war survivors with traumatic injuries [2].

The rapid changes in societies have led to changes in factors affecting human health (physical, chemical, biological and social factors). This development, in turn, has led to serious changes in the pattern of diseases, which necessitates the recognition and application of new methods, especially holistic. In parallel with these changes, the increasing use of new methods in medicine is evident. One of these methods, which has recently been considered scientifically in the world, is the spiritual-religious practice [3]. Studies have shown that when faced with a chronic illness, many people turn to their spirituality and religious beliefs. Research has also shown that people who are medically ill often use spiritual and religious practices to cope with their illness [4]. Spiritual care is necessary not only for people with religious beliefs but also for all people. Nursing researches show that the spiritual dimension is one of the most important aspects of nursing in caring for and relieving patients' pain [5]. At the end of December 2019, the spread of a new infectious disease was reported in China, caused by a new coronavirus and officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization. This virus has infected Iran, like other countries in the world [6]. The most common symptoms of this disease include fever, cough, and pulmonary involvement, which are sometimes accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms. Pulmonary damage also causes fibrosis of lung tissue, difficulty breathing, and decreased arterial oxygen levels [7]. Quality of life, which is one of the most important components of mental health, is a multidimensional and mental concept that originates from people's beliefs and perceptions. This multidimensional and mental concept not only reflects the individual's assessment of his or her environment, but also includes physical health, psychological state, autonomy, social relationships, and personal and spiritual beliefs [8]. Quality of life can be considered as the relationship between a person's health status on the one hand and the ability to pursue life goals on the other hand [9]. Since the concept of quality of life is one of the important concepts of life that is directly related to the concept of life satisfaction, so the awareness of the care team and nurses of the concept, dimensions, and factors of quality of life is one way to improve quality of life and patient satisfaction. Paying attention to improving the quality of life is an important key to community health [10].

Life satisfaction is the evaluation of the quality of life based on selected individual criteria and if the living conditions are in line with individual criteria, life satisfaction will be higher [11]. In theoretical concepts, the issue of life satisfaction is mentioned as one of the necessary conditions for the effective psychological functioning of a human being. According to the World Health Organization, the four factors that directly affect life satisfaction are physical health, mental health, social relationships, and the environment. Life satisfaction is essential for the overall quality of life [12]. One researcher believes that people who are more satisfied with their life use more effective and appropriate coping methods, experience deeper positive emotions, and have a higher quality of life [13]. Many studies have shown that the categories of life satisfaction and happiness are directly related to religious beliefs and behaviors [14].

Considering the importance and potential role of spiritual-religious practice as a complementary approach in health promotion, this study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of spiritual-religious practice on the quality of life and life satisfaction of hospitalized war survivors with COVID-19.

Materials & Methods

In this quasi-experimental clinical trial, the effect of spiritual-religious practice on the quality of life and life satisfaction of war survivors with COVID-19 admitted to Sasan Hospital in Tehran in 2021 was performed. Sampling was done by convenience sampling and division into intervention and random control groups. The number of samples was 67 in each group, due to the possibility of sample loss of 10% has been added to the samples (a total of 150 cases). War survivors were divided into two groups of 75 in the intervention and control groups. All participants in the pre-admission study were evaluated for vital signs and para clinics in terms of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were being a war survivor, hospitalization due to COVID-19 disease with a positive PCR test, alertness and those were having any clinical condition such as diagnosed mental problems, drowsiness and confusion, depression, and condition that affected a person's ability to participate in the study, patients admitted to the ICU or died within the first 48 hours of the study were excluded from the study.

Demographic information, history of diseases, and risk factors were assessed at the beginning of the study. Risk factors assessed in the study included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, immune deficiency, malignancy or chemotherapy, hyperlipidemia, organ transplants, AIDS, BMI higher than 40, and recently corticosteroid use. 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) and Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) questionnaires were used to determine the quality of life and life satisfaction scores. The SF-12 questionnaire was developed in 1996 by War-Kasinski and Keller. This questionnaire has 8 subscales that determine the dimensions of quality of life during the last four weeks. These eight dimensions include physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, emotional role, vitality, and mental health. Some questions were answered using yes and no and others in five-point Likert. The score is 12-48. A score of 12-24 indicates a poor quality of life, a score of 25-36 indicates an average quality of life, and a score of 37-48 indicates a good quality of life. So a higher score indicates a better quality of life [15]. Montazeri et al. examined the validity of this questionnaire in Iran. Samples in this study were randomly selected from people aged 15 and over who lived in Tehran. Reliability was assessed using internal consistency and validity was assessed using known group control and convergent validity. Cronbach's alpha was 0.73 for the physical component summary and 0.72 for the psychological component summary. Finally, the findings showed that SF12 is a valid measure of health-related quality of life among the Iranian people [15]. Diner et al. developed a life satisfaction scale for all age groups. The scale consisted of 48 questions that reflected life satisfaction and well-being. 10 questions were related to life satisfaction, which after several studies was finally reduced to 5 questions and used as a separate scale. Questions are answered in a five-point Likert from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Scoring is between 5 and 25. A higher score indicates higher life satisfaction. To determine the validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Iran, 109 students of Islamic Azad University, completed this questionnaire. The validity of the Life Satisfaction Scale was 0.83 using the Cronbach's alpha method and 0.69 using the retest method [16].

This research was approved by School of Nursing & Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The aims of the study were explained to eligible war survivors. After providing complete information about the aims of the study, informed consent was obtained from all participants. In this study, the patient's usual medical treatments were continued according to the physician's instructions and there was no interruption. Participants also had the right to be excluded from the study if they wanted, and it was ensured that there would be no restrictions on receiving the required medical services. The participants received their usual treatment protocol according to the instructions ordered by their physicians, who were independent of the research team. The spiritual-religious practice intervention was performed by the war survivor himself with the intention of healing and recovery so that the war survivors prayed for themselves and since they were aware of the intervention, it was not possible to blind them and the data analysis was analyzed by the researcher (single-blinded). War survivors were asked to recite “Surah Al-Hamd” and “Ya Allah” for the sake of healing and recovery. The duration of the intervention was seven days (from the beginning of hospitalization in Sasan Hospital in March and April 2021) three times a day for 5 minutes each time, which included a total of 21 interventions sessions- spiritual-religious practice with three times “Surah Al-Hamd” and then 66 times “YaAllah”. Intervention times were considered with the patient's medication (approximately every 8 hours). War survivors in the intervention group (75 people) were given a registration form for spiritual-religious practice and were asked to check the registration form by checking each time. Participants were taught how to record data on spiritual-religious practice. During the 7-day intervention period, at the beginning of each day, the intervention record was checked and also remind of the spiritual practices. War survivors who had practiced less than 15 times were excluded from the study.

The data were analyzed by SPSS 20. First, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov quantitative data normality test was performed and parametric tests were used to analyze the data of variables with normal distribution. Data analysis was analyzed using Chi-square, independent t-test, and Fisher's exact test. GEE analysis was used to determine factors that are independently related to the quality of life and life satisfaction.

Findings

Of the 183 war survivors who met the inclusion criteria, 153 war survivors were reluctant to participate in the study (Participation rate: 81.9%). The data of war survivors done religious spiritual care more than 15 times were analyzed (and the data with less than15 times were excluded from the study (%1.6)). The total data of 150 war survivors who completed the intervention are presented in this study. The mean age of participants was 56.48±4.74, and 56.48±4.74 in the intervention and control groups, respectively (p=0.64). Also, the mean war survivor disability rate was 14.16±11.646, and 16.09±15.56 in the intervention and control groups, respectively (p=0.39). Most participants in both intervention and control groups were male, married, unemployed, and above Diploma (Table 1).

There were no significant differences between the two groups in all dimensions at the beginning of the study (p>0.05). The differences between before and after the intervention were significant in the intervention group in the following dimensions: physical functioning; role physical; mental health; social functioning; bodily pain; general health; mental Component Summary and Physical Component Summary (p<0.05). The differences in physical function, role physical, social functioning, bodily pain, general health, mental Component summary, and physical component summary were significant in the control group between before and at the end of the study, as well (p<0.05; Table 2).

Table 1) Results of demographic and clinical features in hospitalized war survivors with COVID-19 before the intervention

Table 2) Mean results of quality of life score in war survivors admitted with COVID-19 in two groups at the beginning and end of the study

There were no significant differences between the two groups at the beginning of the study (p>0.05). The mean score of life satisfaction was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group. At the end of the study, the scores of life satisfaction had significant differences in the intervention and control groups (p<0.05; Table 3).

Table 3) Comparison of the mean and standard deviation of life satisfaction scores in war survivors hospitalized with COVID-19 before and after intervention

The mean differences between the two groups showed that role of physical and Physical Component Summary had significantly increased in the intervention group who have spiritual practice (Table 4).

Table 4) Comparison of the mean±SD difference in the quality of life and life satisfaction between two groups

Discussion

This study showed that spiritual-religious practice with healing intentions improved role physical, Physical Component Summary, and life satisfaction among war survivors hospitalized due to COVID-19.

Spiritual care hasn’t found its proper position in the care setting of Iran yet, and members of the healthcare team do not have sufficient training to provide this kind of care [17]. However Spiritual care is important in nursing practice, and spiritual well-being and spiritual care are associated with better health [18].

Currently, the use of complementary and alternative medicines in COVID-19 seems to be a common practice all over the world. Limited research exists from human clinical trials regarding the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicines in COVID-19. Several clinical trials on complementary and alternative medicines have been registered in the Middle-east such as Meditation or holy Quran recitation, cupping therapy (Hijama), acupuncture, massage, specific nutritional tonics, and herbs such as honey, dates, figs, peaches, garlic, olives, Anthemis hyaline (chamomile) and black cumin seeds [19].

In recent decades, much scientific research has been done on the impact of spiritual care on health improvement. The results of most studies indicated that spiritual care had a potential beneficial effect on the quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness [20].

In our study most participants had risk factors and the most important risk factors were blood pressure and diabetes, which the rate was similar to the other studies [21-25]. The desire to pray is a natural feeling and spiritual care is a basic need in human beings. Many people pray when they are sick, but the clinical effects of spiritual care are not well understood [26]. The results of Mazandarani et al.'s study showed that Spiritual counseling provides self-efficacy, self-control, and daily self-calculation in patients and improves the quality of life (in emotional function) in patients [27]. A study on spiritual health in war survivors showed that there is a direct relationship between spiritual health and general health and quality of life (there were significant differences between spiritual health and physical functioning and bodily pain). This study revealed that higher spiritual health is accompanied by a better quality of life and general health [28]. The other study investigates the relationship between spirituality and life satisfaction among patients with spinal cord injury. Data analysis indicated that there was a significant positive correlation between life satisfaction and psychological/spiritual factors of the quality of life [29].

Different studies used a variety of Quranic recitations to practice spiritual healing including Surah “Al-Hamd”; “Altowhid”; “Alqadr” and “YaAllah recitation” for the sake of healing and recovery [30-34]. Farzin Ara et al.'s study showed that “Ya Allah” reduced the patients’ pain after orthopedic surgery [30]. Also in the study of Etefagh et al., reciting the “Surah Alhamd” “Surah Altowhid” and “Surah Alqadr” reduced the severity of clinical symptoms in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome [31]. In Forouhari et al.'s study, the effect of Quran sound on labor pain was investigated. The results of this study showed that listening to the Quran is a complementary method to reduce labor pain in nulliparous women [32]. Hassanpour et al. investigated the effect of Hazrat Zahra’s praises recitations on the pain. The results showed that reciting Hazrat Zahra’s praises reduced pain severity in hospitalized patients [33]. Another study on the effect of the Holy Quran on pain due to heel-stick showed that there was no significant difference between the pain of the patients before and after the intervention [34].

Bartlett et al. find that spiritual transcendence such as reading the bible and praying frequently as is independently associated with happiness psychological health, subjective well-being, and life satisfaction [35]. However, spirituality and religious beliefs were better predictors of happiness and quality of life for Protestants and Catholics than Jews [36].

The main barriers to spiritual care are the difficulty in defining spirituality; lack of palliative care departments; lack of clear guidelines for the nurse's role in providing spiritual care and nurses' lack of time and high workloads to provide spiritual care [17, 18]. Also in this study, most participants were male and the age range of most of them in both groups was 55-64 years because of choosing war survivors for this study. Therefore, the impact of the intervention on women as well as other age groups needs further investigation. Another limitation in this study was that patients with COVID-19 were unable to participate in spiritual-religious practice due to weakness and lethargy.

Conclusion

People who are medically ill often use spiritual and religious practices to cope with their illness. Spiritual care is necessary not only for people with religious beliefs but also for all people. As the World Health Organization confirmed spiritual health is an important dimension of health on which health can be enjoyed and is an important base for other dimensions of health. This study showed that spiritual-religious practice with healing intentions in addition to routine medical treatments improved role physical, Physical Component Summary, and life satisfaction among war survivors hospitalized due to COVID-19. However, more research is needed to clarify the various dimensions recommended.

Acknowledgments: I would like to express my deep thanks to all war survivors enrolled in the current study for their kind cooperation to complete the present trial; and Dr. Marziyeh Asgari, Mrs Bajouli and Dr. Zohreh Ganjparvar who have contributed to the various stages of the present study. The authors are grateful for the guidance and spiritual support of the honorable master Akram Jahangir throughout the study.

Ethical Permissions: This research was approved with the ethics code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1400.006 and Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials code IRCT20210227050517N1.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflict of interest was reported.

Authors’ Contribution: Mahdavi R (First Author), Main Researcher (25%); Esmaeili R (Second Author), Discussion Writer (25%); Mousavi B (Third Author), Methodologist/Discussion Writer/Statistical Analyst (25%); Fani M (Forth Author), Assistant Researcher (25%)

Funding/Support: The present study was extracted from the master thesis by Raheleh Mahdavi in Sasan hospital and was conducted with the financial support of School of Nursing & Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Keywords:

Spiritual Therapies [MeSH], Quality of Life [MeSH], Patient Satisfaction [MeSH], Survivors [MeSH], COVID-19 [MeSH]

References

1. Taebi G, Soroush MR, Modirian E, Khateri S, Mousavi B, Ganjparvar Z, et al. Human costs of Iraq's chemical war against Iran; an epidemiological study. Iranian J War Public Health. 2015;7(2):115-21. [Persian] [Link]

2. Tavallie SA, Assari S, Habibi M, Nouhi S, Ghanei M. Correlation between cause and time of death with types of casualty in veterans. J Mil Med. 2005;7(3):211-7. [Persian] [Link]

3. Jahangir A, Khodaee Sh, Karbakhsh M, Shariati M. Intercessory prayer and ferritin and hemoglobin in major thalassemia: A pilot study. PAYESH. 2008;7(4):363-7. [Persian] [Link]

4. Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Lefebvre J, Underwood L, Caldwell DS, Drew J, et al. Living with rheumatoid arthritis: The role of daily spirituality and daily religious and spiritual coping. J Pain. 2001;2(2):101-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1054/jpai.2001.19296]

5. Sharifnia Sh, Hojjati H, Nazari R, Qorbani M, Akhoondzade G. The effect of prayer on mental health of hemodialysis patients. J Critic Care Nurs. 2012;5(1):29-34. [Persian] [Link]

6. Shahyad S, Mohammadi MT. Psychological impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on mental health status of society individuals: A narrative review. J Mil Med. 2020;22(2):184-92. [Persian] [Link]

7. Jalalvand M, Akhtari M, Farhadi E, Mahmoudi M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) immunopathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Iran J Biol. 2020;4(7):251-9. [Persian] [Link]

8. Jahangiri MM, Rafee Mohammadi N. Effect of logotherapy with quran recitation and prayer on quality of life in women with major depressive disorder. Islam life style. 2018;2(2). [Persian] [Link]

9. Khani H, Joharinia M, Kariminasab M, Ganji R, Azadmarzabadi E, Shakeri M, et al. Evaluation of quality of life in amputee veterans in Mazandaran. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2011;3(1):49-56. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jnkums.3.1.8]

10. Esmaeili R, Esmaeili M. Quality of life in the elderly: A meta-synthesis. J Res Relig Health. 2018;4(2):105-16. [Persian] [Link]

11. Roohi G, Asayesh H, Abbasi A, Ghorbani M. Some influential factors on life satisfaction in Gorgan veterans. Iran J War Public Health. 2011;3(3):13-8. [Persian] [Link]

12. Vahedi Kojnagh H, Afshari A, Rezaei Malajagh R, Eghbali A, Taheri M. The prediction of the elderly's life satisfaction based on health-promoting lifestyle. Aging Psychol. 2020;6(3):297-85. [Persian] [Link]

13. Molaei B, Nadrmohammadi M, Molavi P, Azarkolah A, Sharei AS, Alizadehgoradel J. The role of spiritual intelligence and life satisfaction in the mental health. Iranian J Nurs Res. 2021;15(6):47-55. [Persian] [Link]

14. Ferriss AL. Religion and the quality of life. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3(3):199-215. [Link] [DOI:10.1023/A:1020684404438]

15. Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Omidvari S. The Iranian version of 12-item short form health survey (SF-12): Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:341. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-341]

16. Bayani AA, Koocheky AM, Goodarzi H. The reliability and validity of the satisfaction with life scale. 2007;3(11):259-65. [Persian] [Link]

17. Farahani AS, Rassouli M, Salmani N, Mojen LK, Sajjadi M, Heidarzadeh M, et al. Evaluation of health-care providers' perception of spiritual care and the obstacles to its implementation. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(2):122-9. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/apjon.apjon_69_18]

18. Rushton L. What are the barriers to spiritual care in a hospital setting?. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(7):370-4. [Link] [DOI:10.12968/bjon.2014.23.7.370]

19. Paudyal V, Sun S, Hussain R, Abutaleb MH, Hedima EW. Complementary and alternative medicines use in COVID-19: A global perspective on practice, policy and research. Rese Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18(3):2524-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.05.004]

20. Chen J, Lin Y, Yan J, Wu Y, Hu R. The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: A a systematic review. Palliative Med. 2018;32(7):1167-79. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/0269216318772267]

21. Nasrollahzadeh Sabet M, Khanalipour M, Gholami M, Sarli A, Rahimi Khorrami A, Esmaeilzadeh E. Prevalence, clinical manifestation and mortality rate in Covid-19 patients with underlying diseases. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2020;23(5):740-9. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/JAMS.23.COV.5797.1]

22. Sheikhi F, Mirkazehi Z, Azarkish F, Kalkali S, Seidabadi M, Mirbaloochzehi A. Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with COVID-19 in Iranshahr Hospitals, southeastern Iran in 2020. J Mar Med. 2021;3(1):46-52. [Persian] [Link]

23. Liu L, Lei X, Xiao X, Yang J, Li J, Ji M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease-2019 in Shiyan city, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:284. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00284]

24. Akhavizadegan H, Aghaziarati M, Roshanfekr Balalami MQ, Arman Boroujeny Z, Taghizadeh F, et al. Investigating the association between comorbidity with chronic diseases and icu hospitalization/death rate in the elderly infected with COVID-19. SALMAND. 2021;16(1):86-101. [Persian] [Link]

25. Dadgari A, Mirrezaei SM, Talebi SS, Alaghemand Gheshlaghi Y, Rohani-Rasaf M. Investigating some risk factors related to the covid-19 pandemic in the middle-aged and elderly. SALMAND. 2021;16(1):102-11. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.32598/sija.16.1.3172.1]

26. Jahangir A, Mousavi B, Mahdavi R, Asgari M, Karbakhsh M. The effect of spiritual practice along with routine medical care on the recovery of patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. Iranian J War Public Health. 2020;12(4):213-21. [Link] [DOI:10.52547/ijwph.12.4.213]

27. Sun XH, Liu X, Zhang B, Wang YM, Fan L. Impact of spiritual care on the spiritual and mental health and quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11(8):449-62. [Link] [DOI:10.5498/wjp.v11.i8.449]

28. Pouraboli B, Hosseini SV, Miri S, Tirgari B, Arab M. Relationship between spiritual health and quality of life in post-traumatic stress disorder veterans. Iran J War Public Health. 2015;7(4):233-9. [Persian] [Link]

29. Brillhart B. A study of spirituality and life satisfaction among persons with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Nurs. 2005;30(1):31-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2005.tb00353.x]

30. Farzin Ara FZM, Mousavi Garmaroudi M, Behnam Vashani H, Talebi Sh. Comparative study of the effect of allah's recitation and rhythmic breathing on postoperative pain in orthopedic patients. J Anesthesiol Pain. 2018;9(1):68-78. [Persian] [Link]

31. Etefagh L, Azma K, A Jahangir. Prayer therapy: Using verses of Fatiha al-kitab, qadr and Towhid surahs on patients suffering from tunnel karp syndrome. Interdiscip Quran Stud. 2009;1(2):27-31. [Persian] [Link]

32. Forouhari S, Honarvaran R, Masumi R. Investigating the auditory effects of Holy Quranic voice on labor pain. Quran Med. 2017;2(3):14-8. [Persian] [Link]

33. Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Khodadi K, Khaledifar A, Salehi S. The effect of recommended recitals on the severity of perceived pain in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery: A randomized clinical trial. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2015;16(6):111-8. [Persian] [Link]

34. Vasigh A, Tarjoman A, Borji M. The effect of spiritual-religious interventions on patients' pain status: Systematic review. Anaesthesia Pain Intensive Care. 2018;22(4). [Link]

35. Bartlett SJ, Piedmont R, Bilderback A, Matsumoto AK, Bathon JM. Spirituality, well-being, and quality of life in people with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(6):778-83. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/art.11456]

36. Cohen A. The importance of spirituality in well-being for Jews and Christians. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3(3):287-310. [Link] [DOI:10.1023/A:1020656823365]