Volume 13, Issue 4 (2021)

Iran J War Public Health 2021, 13(4): 267-270 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2021/09/4 | Accepted: 2021/10/4 | Published: 2022/01/24

Received: 2021/09/4 | Accepted: 2021/10/4 | Published: 2022/01/24

How to cite this article

Mahmood Niazy S, Sameen E, Hadi Najm S, Abed Gatea A. Assessment of the Contributing Factors to Head Injury and its Health Outcomes. Iran J War Public Health 2021; 13 (4) :267-270

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1018-en.html

URL: http://ijwph.ir/article-1-1018-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Department of Community Health, Medical-Technical Institute, Baghdad Middle Technical University, Baghdad, Iraq

2- Medical-Technical Institute, Baghdad Middle Technical University, Baghdad, Iraq

3- Ministry of Health, Baghdad, Iraq

2- Medical-Technical Institute, Baghdad Middle Technical University, Baghdad, Iraq

3- Ministry of Health, Baghdad, Iraq

Full-Text (HTML) (526 Views)

Introduction

Painful brain injury is a very important cause of death and morbidity in developed countries. Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death among people under 45 years worldwide [1]. When referring to brain injury, the term "traumatic brain injury" is preferred to the use of "less specific and more general head injury". While the skull fracture may indicate the presence of painful head injury, neurological symptoms within the skull or proof of pathology are necessary to diagnose head injuries. It is not always necessary for a head injury to be painful due to direct trauma [2]. Every year, head injuries contribute to a large number of deaths and cases of permanent disability. In Europe, the annual incidence of head injury in hospital emergency departments is 2.3 per 1000 person-years [3]. A bump, blow or jolt to the head, or head injury penetrates the brain’s normal function. The intensity of traumatic head injuries may range from "mild" to "severe". There are reasons or multiple factors that contribute to such injuries [4]. The average annual percentage of head injuries by external causes in the United States in 2002-2006 was as follows: increase in emergency department visits related to injuries head (14.4%) and treatment in hospitals (19.5%), an increase of 62% in the related head injuries fall in emergency departments among children aged 14 years and younger, an increase in the associated head injuries falls among adults aged 65 and older; an increase of 46% in the emergency department visits, and a 34% increase in hospitals, and an increase of 27% in deaths related to head injuries [5].

Mortality rates in South Africa are six times higher, and the occurrence of road traffic injuries is doubled, compared to the global average. Major risk factors for head injuries are the age above 60 years and male gender at any age group [6]. In the United States, the main cause of head injury is tall, followed by car accidents and attacks against things [7]. It is economically, socially, and personally a devastating case, which embodies the adage that "prevention is better than cure". In the future, it will depend on improved patient outcomes response organization shocks systems, especially to prevent the potential effects that can be reversed to secondary brain injury[8].

Since there was no independent study to determine the contributing factors of traumatic head injuries in Baghdad province, this study aimed to assess the contributing factors of traumatic head injury and its health outcomes.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive study was conducted and involved all traumatic head injuries admitted to the Emergency Department of Baghdad Teaching Hospital. Emergency Departments that receive the patients with head trauma in a teaching hospital were selected as a rich field to collect the study participants by purposive sample. The participants were selected by probability sampling approach. A total of 60 patients exposed to traumatic head injuries during the study period were followed for one month to assess the Glasgow Coma Scale and Glasgow Outcome Scale.

A questionnaire specially designed for this purpose was used for interviewing the injured subjects or their attendants when their condition did not warrant the interview. The collected information consisted of personal identification data (age, gender, marital status, education, and occupation) and the contributing factors. Glasgow Coma Scale was used to describe the extent of impaired consciousness objectively. The scale assesses patients according to three aspects of responsiveness: eye-opening, motor, and verbal responses [9]. Glasgow Outcome Scale was used to assess the patients' recovery in five categories (Death, Persistent vegetative state, severe disability, moderate disability, and low disability) [10].

Was the study approved by the Ethics Committee of Baghdad University. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients or their attendance.

Data statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 software. Also, a descriptive statistical analysis approach that includes frequencies and percentages was used for quantitative variables.

Findings

According to Table 1, out of 60 patients, 20 (33.3%) aged 20-29 years, 41 (68.3%) were single, 53 (88.3%) were male, 28 (46.7%) had primary schools graduated, and 36 (60%) had free work.

Table 1) Demographic Characteristics of the studied patients (N=60)

Table 2 showed that RTA was the most traumatic head injury, especially automobile, which constituted (68.3%) of all the contributing factors.

Table 2) Contributing Factors of Traumatic Head Injuries

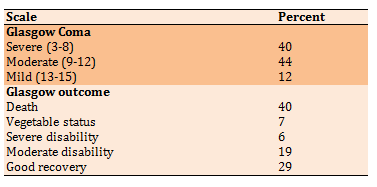

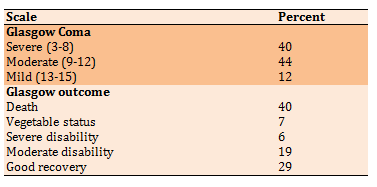

Table 3 indicated that most traumatic head injuries patients had moderate to severe levels of consciousness. Also, most traumatic head injuries patients died (40%).

Table 3) Glasgow Coma Scale and Health Outcome (Glasgow outcome scale)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first project to assess the contributing factors of traumatic head injuries and their health outcomes in Baghdad city. Head injuries are very serious because they can lead to permanent disability, mental retardation, and death. For most people, brain injuries or head injuries are considered unacceptable when engaging in accidents or different types of activities from the workplace. Conversely, head injuries are considered acceptable risks when engaging in sports or different types of activities. Out of 60 patients exposed to such injuries, 20 (33.3%) aged 20-29 years, 41 (68.3%) were single, 53 (88.3%) were male, 28 (46.7%) had primary schools graduated, and 36 (60%) had free work. These results are confirmed in many studies [11-13]. The high morbidity rate among younger age groups in the present study is in accordance with that concluded by Lin and Kraus [14] in developing countries and also that of et al. [15].

The higher incidence of accidents among males concluded in our study is consistent with the findings of other previous studies in other countries [16-19]. This association is not unexpected based on other global estimates and is likely linked to gender roles and high-risk behaviors [20, 21]. Wefaqq Mahdi et al., in 2018, performed the study to assess the contributing factors to head traumatic patients and

its relation to their outcomes at Al-Hilla Teaching Hospital. They concluded that the majority of the study samples (89.0%) were male and 50% aged 18-28 years with low educational levels; these factors were positively and significantly associated with the outcomes of head trauma [22]. Our findings indicated that the most traumatic head injuries were caused by Road Traffic accidents, especially automobiles, which constituted (68.3%) compared to the remaining accidents because injuries are caused by decreased attention, chaotic traffic, and unintentional. This result is consistent with a prospective analysis study conducted to investigate the outcomes in patients with a severe head injury. Their findings revealed that a road traffic accident was the commonest (83.64%) cause of severe head injury [23]. Also, the other study conducted by Gururaj indicated that the majority (60%) of cases of traumatic brain injury are due to road traffic injuries (RTI) [24].

In the current study, the patients exposed to traumatic head injuries had a severe modern loss of consciousness, and 40% USA, head injuries are estimated at 1.7 million each year. About 3% of these accidents lead to death. In adults, the infection rate is more than any other age group, and it is often due to falling injuries, car accidents, collisions, bumping into the body, or due to assaults [25].

The evidence base for the early management of head-injured patients (assessment, resuscitation, and early management) confirmed that 38% of these patients suffer from severe levels of conscious loss and the outcomes depict death to vegetative [26].

Conclusion

Road Traffic Accidents are the most common factor which causes head injury amongst young adults leading to death. The Ministry of Health needs to address this serious problem to develop healthcare professionals who have specific training and experience in brain injury.

Acknowledgments: -

Ethical Permissions: This study does not have ethical code.

Conflicts of Interests: -

Authors’ Contribution: Mahmood Niazy Sh. (First Author), Introduction Writer (25%); Sameen E.K. (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Hadi Najm Sh. (Third Author), Discussion Writer (25%); Abed Gatea A. (Fourth author), Assistant Researcher (25%).

Funding/Support: -

Painful brain injury is a very important cause of death and morbidity in developed countries. Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death among people under 45 years worldwide [1]. When referring to brain injury, the term "traumatic brain injury" is preferred to the use of "less specific and more general head injury". While the skull fracture may indicate the presence of painful head injury, neurological symptoms within the skull or proof of pathology are necessary to diagnose head injuries. It is not always necessary for a head injury to be painful due to direct trauma [2]. Every year, head injuries contribute to a large number of deaths and cases of permanent disability. In Europe, the annual incidence of head injury in hospital emergency departments is 2.3 per 1000 person-years [3]. A bump, blow or jolt to the head, or head injury penetrates the brain’s normal function. The intensity of traumatic head injuries may range from "mild" to "severe". There are reasons or multiple factors that contribute to such injuries [4]. The average annual percentage of head injuries by external causes in the United States in 2002-2006 was as follows: increase in emergency department visits related to injuries head (14.4%) and treatment in hospitals (19.5%), an increase of 62% in the related head injuries fall in emergency departments among children aged 14 years and younger, an increase in the associated head injuries falls among adults aged 65 and older; an increase of 46% in the emergency department visits, and a 34% increase in hospitals, and an increase of 27% in deaths related to head injuries [5].

Mortality rates in South Africa are six times higher, and the occurrence of road traffic injuries is doubled, compared to the global average. Major risk factors for head injuries are the age above 60 years and male gender at any age group [6]. In the United States, the main cause of head injury is tall, followed by car accidents and attacks against things [7]. It is economically, socially, and personally a devastating case, which embodies the adage that "prevention is better than cure". In the future, it will depend on improved patient outcomes response organization shocks systems, especially to prevent the potential effects that can be reversed to secondary brain injury[8].

Since there was no independent study to determine the contributing factors of traumatic head injuries in Baghdad province, this study aimed to assess the contributing factors of traumatic head injury and its health outcomes.

Instrument and Methods

This descriptive study was conducted and involved all traumatic head injuries admitted to the Emergency Department of Baghdad Teaching Hospital. Emergency Departments that receive the patients with head trauma in a teaching hospital were selected as a rich field to collect the study participants by purposive sample. The participants were selected by probability sampling approach. A total of 60 patients exposed to traumatic head injuries during the study period were followed for one month to assess the Glasgow Coma Scale and Glasgow Outcome Scale.

A questionnaire specially designed for this purpose was used for interviewing the injured subjects or their attendants when their condition did not warrant the interview. The collected information consisted of personal identification data (age, gender, marital status, education, and occupation) and the contributing factors. Glasgow Coma Scale was used to describe the extent of impaired consciousness objectively. The scale assesses patients according to three aspects of responsiveness: eye-opening, motor, and verbal responses [9]. Glasgow Outcome Scale was used to assess the patients' recovery in five categories (Death, Persistent vegetative state, severe disability, moderate disability, and low disability) [10].

Was the study approved by the Ethics Committee of Baghdad University. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients or their attendance.

Data statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 software. Also, a descriptive statistical analysis approach that includes frequencies and percentages was used for quantitative variables.

Findings

According to Table 1, out of 60 patients, 20 (33.3%) aged 20-29 years, 41 (68.3%) were single, 53 (88.3%) were male, 28 (46.7%) had primary schools graduated, and 36 (60%) had free work.

Table 1) Demographic Characteristics of the studied patients (N=60)

Table 2 showed that RTA was the most traumatic head injury, especially automobile, which constituted (68.3%) of all the contributing factors.

Table 2) Contributing Factors of Traumatic Head Injuries

Table 3 indicated that most traumatic head injuries patients had moderate to severe levels of consciousness. Also, most traumatic head injuries patients died (40%).

Table 3) Glasgow Coma Scale and Health Outcome (Glasgow outcome scale)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first project to assess the contributing factors of traumatic head injuries and their health outcomes in Baghdad city. Head injuries are very serious because they can lead to permanent disability, mental retardation, and death. For most people, brain injuries or head injuries are considered unacceptable when engaging in accidents or different types of activities from the workplace. Conversely, head injuries are considered acceptable risks when engaging in sports or different types of activities. Out of 60 patients exposed to such injuries, 20 (33.3%) aged 20-29 years, 41 (68.3%) were single, 53 (88.3%) were male, 28 (46.7%) had primary schools graduated, and 36 (60%) had free work. These results are confirmed in many studies [11-13]. The high morbidity rate among younger age groups in the present study is in accordance with that concluded by Lin and Kraus [14] in developing countries and also that of et al. [15].

The higher incidence of accidents among males concluded in our study is consistent with the findings of other previous studies in other countries [16-19]. This association is not unexpected based on other global estimates and is likely linked to gender roles and high-risk behaviors [20, 21]. Wefaqq Mahdi et al., in 2018, performed the study to assess the contributing factors to head traumatic patients and

its relation to their outcomes at Al-Hilla Teaching Hospital. They concluded that the majority of the study samples (89.0%) were male and 50% aged 18-28 years with low educational levels; these factors were positively and significantly associated with the outcomes of head trauma [22]. Our findings indicated that the most traumatic head injuries were caused by Road Traffic accidents, especially automobiles, which constituted (68.3%) compared to the remaining accidents because injuries are caused by decreased attention, chaotic traffic, and unintentional. This result is consistent with a prospective analysis study conducted to investigate the outcomes in patients with a severe head injury. Their findings revealed that a road traffic accident was the commonest (83.64%) cause of severe head injury [23]. Also, the other study conducted by Gururaj indicated that the majority (60%) of cases of traumatic brain injury are due to road traffic injuries (RTI) [24].

In the current study, the patients exposed to traumatic head injuries had a severe modern loss of consciousness, and 40% USA, head injuries are estimated at 1.7 million each year. About 3% of these accidents lead to death. In adults, the infection rate is more than any other age group, and it is often due to falling injuries, car accidents, collisions, bumping into the body, or due to assaults [25].

The evidence base for the early management of head-injured patients (assessment, resuscitation, and early management) confirmed that 38% of these patients suffer from severe levels of conscious loss and the outcomes depict death to vegetative [26].

Conclusion

Road Traffic Accidents are the most common factor which causes head injury amongst young adults leading to death. The Ministry of Health needs to address this serious problem to develop healthcare professionals who have specific training and experience in brain injury.

Acknowledgments: -

Ethical Permissions: This study does not have ethical code.

Conflicts of Interests: -

Authors’ Contribution: Mahmood Niazy Sh. (First Author), Introduction Writer (25%); Sameen E.K. (Second Author), Assistant Researcher (25%); Hadi Najm Sh. (Third Author), Discussion Writer (25%); Abed Gatea A. (Fourth author), Assistant Researcher (25%).

Funding/Support: -

Keywords:

References

1. Osmond MH, Klassen TP, Wells GA, Correll R, Jarvis A, Joubert G, et al. CATCH: a clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury. CMAJ. 2010;182(4):341-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1503/cmaj.091421] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, eds. Atlas of advanced trauma life support for doctors. 8th Edition. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008. [Link]

3. Nguyen R, Fiest KM, McChesney J, Kwon CS, Jette N, Frolkis AD, et al. The international incidence of traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(6):774-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1017/cjn.2016.290] [PMID]

4. Amara J, Iverson KM, Krengel M, Pogoda TK, Hendricks A. Anticipating the traumatic brain injury-related health care needs of women veterans after the Department of Defense change in combat assignment policy. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(2):e171-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2013.12.004] [PMID]

5. Armistead-Jehle P, Soble JR, Cooper DB, Belanger HG. Unique aspects of traumatic brain injury in military and veteran populations. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017;28(2):323-337. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.12.008] [PMID]

6. Gerritsen H, Samim M, Peters H, Schers H, van de Laar FA. Incidence, course and risk factors of head injury: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020364. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020364] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Asken BM, Sullan MJ, DeKosky ST, Jaffee MS, Bauer RM. Research gaps and controversies in chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A review. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1255-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2396] [PMID]

8. Asken BM, DeKosky ST, Clugston JR, Jaffee MS, Bauer RM. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) findings in adult civilian, military, and sport-related mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI):A systematic critical review. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(2):585-612. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s11682-017-9708-9] [PMID]

9. Ghelichkhani P, Esmaeili M, Hosseini M, Seylani K. Glasgow Coma Scale and FOUR score in predicting the mortality of trauma patients; a diagnostic accuracy study. Emerg (Tehran). 2018;6(1):e42. [Link]

10. Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15(8):573-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/neu.1998.15.573] [PMID]

11. Leidman E, Maliniak M, Saleh A, Hassan A, Hussain SJ, Bilukha OO. Road traffic fatalities in selected governorates of Iraq from 2010 to 2013: prospective surveillance. Conflict Health. 2016;10(2):26913063. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13031-016-0070-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Saad I, Mahdi A, Mustafa W. Risk factors and pattern of injuries in motorcycle accidents in holy Karbala. Karbala J Med. 2013;6(1):1552-60. [Link]

13. Useche A, Gómez V, Cendales B, Alonso F. Working conditions, job strain, and traffic safety among three groups of public transport drivers. Saf Health Work. 2018;9(4):454-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.shaw.2018.01.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Lin MR, Kraus JF. A review of risk factors and patterns of motorcycle injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41(4):710-22. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.aap.2009.03.010] [PMID]

15. Begg DJ, Langley JD, Reeder AI. Motorcycle crashes in New Zealand resulting in death and hospitalisation. I: Introduction methods and overview. Accid Anal Prev. 1994;26(2):157-64. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0001-4575(94)90085-X]

16. Lateef F. Riding motorcycles: is it a lower Limb hazard? Singapore Med J. 2002;43(11):566-9. [Link]

17. Reeder AI, Chalmers DJ, Langley JD. Motorcycling attitudes and behaviours. I. 12 and 13 year old adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health 1992;28(3):225-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02651.x] [PMID]

18. Zargar M, Khaji A, Karbaksh M. Pattern of motorcycle-related injuries in Tehran, 1999 to 2000: a study in 6 hospitals. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12(1-2):81-7. [Link]

19. Segui‐Gomez M and Lopez‐Valdes FJ. Recognizing the importance of injury in other policy forums: the case of motorcycle licensing policy in Spain. Inj Prev. 2007;13(6):429-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/ip.2007.017475] [PMID] [PMCID]

20. Staton CA, Msilanga D, Kiwango G, Vissoci JR, de Andrade L, Lester R, et al. A prospective registry evaluating the epidemiology and clinical care of traumatic brain injury patients presenting to a regional referral hospital in Moshi, Tanzania: challenges and the way forward. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2017;24(1):69-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/17457300.2015.1061562] [PMID]

21. Tran TM, Fuller AT, Kiryabwire J, Mukasa J, Muhumuza M, Ssenyojo H, et al. Distribution and characteristics of severe traumatic brain injury at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Uganda. World Neurosurg. 2015;83(3):269-77. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2014.12.028] [PMID]

22. Wefaqq Mahdi H, Shatha Saadi M, Hassan Alwan B. The contributing factors to head traumatic patients and its relation to their outcomes at Al-Hilla Teaching Hospital. Indian J Public Health Res Develop. 2018;9(12):822-6. [Link] [DOI:10.5958/0976-5506.2018.01947.2]

23. Saini S, Rampal V, Dewan V, Grewal S. Factors predicting outcome in patients with severe head injury: Multivariate analysis. Indian J Neurotrauma. 2012;9(1):46-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnt.2012.04.009]

24. Gururaj G. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries: Indian scenario. Neurol Res. 2002;24(1):24-8. [Link] [DOI:10.1179/016164102101199503] [PMID]

25. Mezue WC, Ndubuisi CA, Erechukwu UA, Ohaegbulam SC. Chest injuries associated with head injury. Niger J Surg. 2012;18(1):8-12. [Link]

26. Moppett KI. Traumatic brain injury: assessment, resuscitation and early management. Br J Anesth. 2007;99(1):18-31. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/bja/aem128] [PMID]